Abstract

Context

Although prayer potentially serves as an important practice in offering religious/spiritual support, its role in the clinical setting remains disputed. Few data exist to guide the role of patient-practitioner prayer in the setting of advanced illness.

Objectives

To inform the role of prayer in the setting of life-threatening illness, this study used mixed quantitative-qualitative methods to describe the viewpoints expressed by patients with advanced cancer, oncology nurses, and oncology physicians concerning the appropriateness of clinician prayer.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, multisite, mixed-methods study of advanced cancer patients (n = 70), oncology physicians (n = 206), and oncology nurses (n = 115). Semistructured interviews were used to assess respondents’ attitudes toward the appropriate role of prayer in the context of advanced cancer. Theme extraction was performed based on interdisciplinary input using grounded theory.

Results

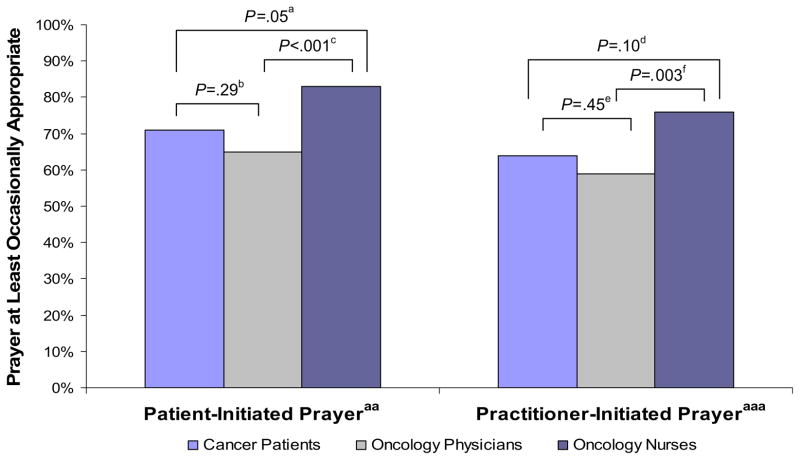

Most advanced cancer patients (71%), nurses (83%), and physicians (65%) reported that patient-initiated patient-practitioner prayer was at least occasionally appropriate. Furthermore, clinician prayer was viewed as at least occasionally appropriate by the majority of patients (64%), nurses (76%), and physicians (59%). Of those patients who could envision themselves asking their physician or nurse for prayer (61%), 86% would find this form of prayer spiritually supportive. Most patients (80%) viewed practitioner-initiated prayer as spiritually supportive. Open-ended responses regarding the appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer in the advanced cancer setting revealed six themes shaping respondents’ viewpoints: necessary conditions for prayer, potential benefits of prayer, critical attitudes toward prayer, positive attitudes toward prayer, potential negative consequences of prayer, and prayer alternatives.

Conclusion

Most patients and practitioners view patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate in the advanced cancer setting, and most patients view prayer as spiritually supportive. However, the appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer is case specific, requiring consideration of multiple factors.

Keywords: Prayer, spirituality, religion, spiritual care, end-of-life care, palliative care

Introduction

Prayer is the most common spiritual practice among patients facing illness1–3 and is a frequent means by which religion and/or spirituality (R/S) helps patients endure and find meaning in the context of advanced illness.1 In patient surveys, between 19% and 67% indicate that they would like prayer from their nurse or physician,4–7 with the frequency of desiring patient-practitioner prayer increasing with greater illness severity and with the form of prayer offered (silent vs. aloud).5,8 In a national sample of physicians, 83% agreed that it was appropriate to pray with patients under some conditions.9 Physician openness toward participating in prayer depends on illness severity,10,11 form of prayer,11 and initiator (patient vs. caregiver).9,11 Only 19% of physicians report at least “sometimes” praying with patients under any conditions.12 Among nurses, between 53% and 66% frequently offer private prayers,13,14 whereas 8%–30% report directly praying with patients.13,15

Recognition of the importance of spiritual care for patients with advanced illness is reflected in the incorporation of spiritual care into palliative care guidelines.16,17 Among advanced cancer patients, spiritual support from the medical team has been shown to be associated with greater hospice use, decreased futile aggressive care, and improved quality of life near death.18 Although prayer potentially serves as an important practice in offering R/S support,1 its role in the clinical setting remains disputed.19,20 Furthermore, little data exist to guide the role of patient-practitioner prayer in the setting of advanced illness. Given the important role of spiritual support in end-of-life care,16,17,21 the importance of prayer among patients facing advanced illness,1–3 and the frequent desire for patient-practitioner prayer among patients facing serious illness,5,22 data are needed to inform the appropriate role of prayer in the setting of advanced illness.

The Religion and Spirituality in Cancer Care study is a multisite, cross-sectional study of advanced, incurable cancer patients, oncology nurses, and oncology physicians using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to characterize patient and practitioner viewpoints of the appropriate role of prayer in the setting of life-threatening illness.

Methods

Study Sample

Patients and practitioners were enrolled between March 3, 2006 and December 31, 2008. Eligibility criteria for patients included diagnosis of an advanced, incurable cancer; active receipt of palliative radiotherapy; age ≥21 years; and adequate stamina to undergo a 45-minute interview. Oncology physicians and nurses were eligible if they cared for incurable cancer patients. Excluded patients were those that met criteria for delirium or dementia by neurocognitive examination (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire23) and those not speaking English or Spanish.

Study Protocol

All research staff underwent a one-day training session in the study protocol and scripted interview. Patients and practitioners were from four Boston, Massachusetts sites: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Patients were randomly selected from radiotherapy schedules; all eligible patients were approached. To mitigate selection bias, study staff informed all potential participants, “You do not have to be religious or spiritual to answer these questions. We want to hear from people with all types of points of view.” Practitioners were identified by collecting e-mail addresses from departmental websites. Participants provided informed consent according to protocols approved by each site’s human subjects committee (institutional review board-approved “implied informed consent” among practitioners). Of 103 patients approached, 75 (response rate [RR] = 73%) participated, with no differences in participants vs. nonparticipants in age, gender, or race. The most frequent reasons for non-participation were “not interested” (n = 8, 32%) and “too busy” (n = 7, 28%). Five patients were too ill to complete the interview, yielding 70 patients (93% of 75). Of 538 physicians and nurses contacted, 339 responded (RR = 63%). Eight reported not seeing incurable cancer patients, giving 331 respondents (98% of 339, 206 physicians and 115 nurses).

Study Measures

Perceptions of Patient-Practitioner Prayer

Participants responded to two prayer scenarios—patient-initiated prayer and practitioner-initiated prayer—with items shown in Table 1. Participants rated (6-point scale) their perceptions of the appropriateness of prayer in each setting, and then provided open-ended explanations of their answers (recorded verbatim). Patients then rated how spiritually supportive patient-practitioner prayer would be for them (4-point scale).

Table 1.

Patient-Practitioner Prayer Survey Questions and Response Options

| Survey Definitions Provided to All the Participants:

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirituality: A search for or a connection to what is divine or sacred.

| |||||

| Religion: A tradition of spiritual beliefs and practices shared by a group of people.

| |||||

| Patient questionnaire | |||||

| 1. Spiritual care example: If a patient asks for prayer, the doctor or nurse praying with the patient. | |||||

| A. Is this appropriate for cancer doctors to do? | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| B. Is this appropriate for cancer nurses to do? | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| C. Please also tell me why you answered questions A and B as you did. | |||||

| Answers recorded verbatim | |||||

| D. How spiritually supportive would this be for you? | |||||

| Not at all supportive | Mildly supportive | Moderately supportive | Very supportive | This does not apply to me (you would never ask for prayer) | |

| 2. Spiritual care example: A religious/spiritual doctor or nurse offering prayer for a patient. | |||||

| A. Is this appropriate for cancer doctors to do? | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| B. Is this appropriate for cancer nurses to do? | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| C. Please also tell me why you answered questions A and B as you did. | |||||

| Answers recorded verbatim | |||||

| D. How spiritually supportive would this be for you? | |||||

| Not at all supportive | Mildly supportive | Moderately supportive | Very supportive | ||

| Nurse questionnaire | |||||

| 1. If a patient asks for prayer, the nurse praying with the patient. | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| 2. A religious or spiritual nurse offering prayer for a patient. | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| 3. Please briefly explain your answers to the last two questions on prayer | |||||

| Answers recorded verbatim | |||||

| Physician questionnaire | |||||

| 1. If a patient asks for prayer, the physician praying with the patient. | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| 2. A religious or spiritual physician offering prayer for a patient. | |||||

| Never appropriate | Rarely appropriate | Occasionally appropriate | Frequently appropriate | Almost always appropriate | Always appropriate |

| 3. Please briefly explain your answers to the last two questions on prayer. | |||||

| Answers recorded verbatim | |||||

Other Measured Variables

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, and years of education were patient reported. Karnofsky performance status was obtained by physician assessment. Practitioner demographics included age, gender, race, field of oncology (medical, radiation, or surgical oncology), and years of practice.

Analytical Methods

Quantitative Methodology

Differences between patient and practitioner quantitatively assessed perspectives of the appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer (dichotomized by a median split to “never” and “rarely” vs. “occasionally,” “frequently,” “almost always,” and “always” appropriate) were assessed using Chi-squared statistics. Predictors of viewing patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate were assessed using univariable logistic regression models. Multivariable analyses were then performed and included all significant and marginally significant (P ≤ 0.10) univariable predictors. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All reported P-values are two-sided and considered significant when less than 0.05.

Qualitative Methodology

The analysis followed standard qualitative methodology24—triangulated analysis, employment of multidisciplinary perspectives (medicine, chaplaincy, theology, sociology), and the use of reflexive narratives—aimed to maximize the transferability of interview data. Transcriptions were independently coded line by line by two researchers (M. J. B. and J. D.), and were then compiled into two preliminary coding schemes. Following principles of grounded theory,25 a final set of themes and subcodes inductively emerged through an iterative process of constant comparison, with input from M. J. B., J. D., A. C. P., and T. A. B. Transcripts were then recoded by M. J. B. and J. D. each working independently. The interrater reliability score was high (kappa = 0.79).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences between patients, physicians, and nurses in regard to age, gender, race, religiousness, spirituality, and religious identification. The majority of patients (87.5%), physicians (78%), and nurses (77%) were both (slightly, moderately, or very) spiritual and religious.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Advanced Cancer Patients, Oncology Physicians, and Oncology Nurses, n = 391

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 70) | Physicians (n = 206) | Nurses (n = 115) | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 38 (50.7) | 87 (42.2) | 113 (98.3) | <0.001 |

| Age, mean (SD)b | 59.9 (11.9) | 40.8 (9.9) | 45.5 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)c | ||||

| White | 59 (84.3) | 157 (78.1) | 109 (95.6) | |

| Black | 7 (10.0) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Asian American, Indian, Pacific Islander | 1 (1.4) | 36 (17.9) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.4) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Other | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Education, mean (SD)d | 15.2 (3.5) | NA | NA | NA |

| Religiousness, n (%)e | ||||

| Not at all religious | 13 (19.1) | 62 (31.2) | 29 (25.9) | |

| Slightly religious | 25 (36.8) | 66 (33.2) | 22 (29.5) | |

| Moderately religious | 17 (25.0) | 54 (27.1) | 43 (38.4) | |

| Very religious | 13 (19.1) | 17 (8.5) | 7 (6.3) | 0.02 |

| Spirituality, n (%)e | ||||

| Not at all spiritual | 5 (7.4) | 30 (15.1) | 6 (5.4) | |

| Slightly spiritual | 14 (20.6) | 57 (28.6) | 18 (16.1) | |

| Moderately spiritual | 24 (35.3) | 75 (37.7) | 58 (51.8) | |

| Very spiritual | 25 (36.8) | 37 (18.6) | 30 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Religious tradition, n (%)e | ||||

| Catholic | 32 (47.1) | 47 (23.6) | 70 (62.5) | |

| Other Christian traditions | 22 (32.4) | 45 (22.6) | 17 (15.2) | |

| Jewish | 5 (7.4) | 51 (25.6) | 6 (5.4) | |

| Muslim | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hindu | 2 (2.9) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Buddhist | 0 (0) | 11 (5.5) | 0 (0) | |

| No religious tradition | 2 (2.9) | 22 (11.1) | 6 (5.4) | |

| Other | 4 (5.88) | 18 (9.1) | 11 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Field of oncology, n (%) | — | |||

| Medical oncology | 112 (54.4) | 90 (78.3) | ||

| Radiation oncology | 46 (22.3) | 13 (11.3) | ||

| Surgical oncology | 32 (15.5) | 7 (6.1) | ||

| Palliative care | 16 (7.8) | 5 (4.4) | <0.001 | |

| Years in practice, n (%) | — | |||

| Resident or fellow | 67 (32.5) | — | ||

| 1–5 | 36 (17.5) | 24 (20.9) | ||

| 6–10 | 35 (17.0) | 24 (20.9) | ||

| 11–15 | 23 (11.2) | 15 (13.0) | ||

| 16–20 | 20 (9.7) | 11 (9.6) | ||

| 21+ | 25 (12.1) | 41 (35.7) | <0.001f | |

SD = standard deviation; NA = not assessed.

P-values based on χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables; P < 0.05 considered significant.

Age missing for 25 physicians and 8 nurses.

Race/ethnicity missing in five physicians and one nurse.

Educational status of physicians and nurses not assessed, but given the training requirements of these professions, can be assumed to be at least a postgraduate education.

Religiousness, spirituality, and religious tradition missing in seven physicians and three nurses.

Resident or fellow category combined with practice one to five years to create single category of less than five years of practice.

Quantitative Assessment of Perceptions of Patient-Practitioner Prayer

The majority of respondents indicated that patient-initiated prayer and practitioner-initiated prayer are at least occasionally appropriate in the cancer setting (Fig. 1). Nurses were significantly more likely than physicians to view both forms of patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate. When comparing participants’ views of patient-vs. practitioner-initiated prayer, patients, nurses, and physicians more frequently rated patient-initiated prayer as at least occasionally appropriate (Chi-squared value = 4.34, degrees of freedom [DF] = 1, P = 0.03; Chi-squared value = 35.97, DF = 1, P < 0.001; Chi-squared value = 30.08, DF = 1, P < 0.001, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Respondents who indicated that patient-practitioner prayer was at least “occasionally appropriate” according to initiation by patients and by practitioners, n = 391. a71.4% vs. 83.5%, χ2 value = 3.8, degrees of freedom = 1; b71.4% vs. 64.6%, χ2 value = 1.2, degrees of freedom = 1; c64.6% vs. 83.5%, χ2 value = 12.9, degrees of freedom = 1; d64.3% vs. 75.7%, χ2 value = 2.8, degrees of freedom = 1; e64.3% vs. 59.2%, χ2 value = 0.6, degrees of freedom = 1; f75.7% vs. 59.2%, χ2 value = 8.8, degrees of freedom = 1. **Response proportions to patient-initiated prayer: (1) patients: never appropriate = 14%, rarely appropriate = 14%, occasionally appropriate = 21%, frequently appropriate = 13%, almost always appropriate = 19%, always appropriate = 19%; (2) oncology physicians: never appropriate = 10%, rarely appropriate = 26%, occasionally appropriate = 34%, frequently appropriate = 12%, almost always appropriate = 13%, always appropriate = 5%; (3) oncology nurses: never appropriate = 4%, rarely appropriate = 12%, occasionally appropriate = 38%, frequently appropriate = 19%, almost always appropriate = 12%, always appropriate = 14%. ***Response proportions to practitioner-initiated prayer: (1) patients: never appropriate = 17%, rarely appropriate = 19%, occasionally appropriate = 30%, frequently appropriate = 4%, almost always appropriate = 16%, always appropriate = 14%; (2) oncology physicians: never appropriate 16%; rarely appropriate 25%; occasionally appropriate 34%; frequently appropriate = 10%; almost always appropriate = 8%, always appropriate = 7%; (3) oncology nurses: never appropriate = 12%, rarely appropriate = 12%, occasionally appropriate = 40%, frequently appropriate = 17%, almost always appropriate = 11%, always appropriate = 7%.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of predictors of perceptions of prayer in the advanced cancer clinical setting are shown in Table 3. In univariable analyses, respondents were more likely to view patient-initiated prayer and practitioner-initiated prayer as at least occasionally appropriate if they were female, more spiritual, and more religious. Perceptions of patient-practitioner prayer also were influenced by religious affiliation, with Catholics being the most likely to perceive patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate. Age, race, years of practice, and field of oncology were not predictive of perceptions of practitioner-initiated prayer. In multivariable analyses, Catholic religious tradition, female gender, and increasing spirituality were significant predictors of viewing patient-initiated prayer as at least occasionally appropriate; whereas Catholic religious tradition was the only factor that remained a significant predictor of viewing practitioner-initiated prayer as at least occasionally appropriate. Notably, in multivariable analyses, respondent type (patient, physician, or nurse) no longer predicted perceptions of patient-practitioner prayer.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Predictors of Viewing Patient- and Practitioner-Initiated Prayer as at Least Occasionally Appropriate in the Clinical Care of Advanced Cancer Patients, n = 379a

| Patient-Initiated Prayer | OR (95% CI) | Pb | AOR (95% CI) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent type | ||||

| Nurse | Ref | Ref | ||

| Patient | 0.70 (0.49–1.01) | 0.05 | 0.85 (0.37–1.96) | 0.75 |

| Physician | 0.36 (0.20–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.44–2.84) | 0.93 |

| Catholic religious traditionc | 2.67 (1.62–4.41) | <0.001 | 1.90 (1.07–3.38) | 0.03 |

| Female gender | 3.13 (1.99–4.92) | <0.001 | 2.14 (1.19–3.83) | 0.01 |

| Spirituality | 2.06 (1.59–2.66) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.28–2.47) | <0.001 |

| Religiousness | 1.46 (1.15–1.86) | 0.002 | 0.99 (0.72–1.37) | 0.95 |

| Practitioner-Initiated prayer

| ||||

| Respondent type | ||||

| Nurse | Ref | Ref | ||

| Patient | 0.76 (0.55–1.05) | 0.10 | 0.63 (0.30–1.29) | 0.30 |

| Physician | 0.47 (0.28–0.78) | 0.003 | 0.73 (0.39–1.35) | 0.74 |

| Catholic religious traditionc | 2.75 (1.73–4.39) | <0.001 | 2.27 (1.36–3.79) | 0.002 |

| Female gender | 1.67 (1.09–2.54) | 0.02 | 1.05 (0.62–1.78) | 0.86 |

| Spirituality | 1.40 (1.11–1.76) | 0.004 | 1.21 (0.90–1.63) | 0.20 |

| Religiousness | 1.35 (1.08–1.69) | 0.009 | 1.10 (0.83–1.47) | 0.50 |

OR = odds ratio; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; Ref = reference category.

Sample reduced from 391 because of missing data.

P < 0.05 considered significant.

Catholic vs. all others (other religious traditions and no religious tradition). Proportion viewing prayer as at least occasionally appropriate according to religious traditions: Catholics (77.9%), Protestants (54.8%), Jews (59.7%), Buddhists (57.1%), Hindus (63.6%), other religious traditions (57.6%), and no religious tradition (50.0%).

A sizable minority of patients (38.6%) indicated they would never ask their nurse or physician for prayer. Of those who would potentially request prayer, most (86.0%) rated receiving prayer in that setting as at least mildly supportive (62.8% moderately to very supportive). Most patients (80.0%) rated a practitioner offering prayer as at least mildly spiritually supportive (55.7% moderately to very supportive).

Qualitative Assessment of Perceptions of Patient-Practitioner Prayer

The six primary themes extracted from participants’ open-ended descriptions of the appropriate role of patient-practitioner prayer in the cancer setting are shown in Table 4 with illustrative quotes. Qualitative theme and subtheme frequencies are provided in Table 5.

Table 4.

Representative Theme Quotes on the Appropriateness of Prayer in the Cancer Care Context According to Advanced Cancer Patients, Oncology Physicians, and Nurses, n = 388

| Theme | Respondent | Representative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Conditions for patient-practitioner prayer | Cancer patient | If the MD is comfortable praying then it is fine but it must be genuine. Prayer is always good because it is a powerful force. Context is very important. It is helpful if both are of the same beliefs but even this is not absolutely necessary. There needs to be a comfort level between people for it to be appropriate. |

| Oncology nurse | As for offering prayer, my bias is not to offer but to let the patient take the lead, so as not to make the mistake of imposing prayer on someone who doesn’t want it, or who sees the oncologist as not responsible for that role. However, there are parts of the country and patient populations where oncologists may be expected to offer prayer more often, and if so, after considering these cultural issues and discussing with peers, it may be appropriate for the oncologist to offer prayer more frequently. | |

| Oncology physician | I think it would only be appropriate for the nurse to offer prayer if she/he knew the patient very well in the context of their religious/spiritual preferences and shared that similarity. | |

| Potential benefits of patient-practitioner prayer | Cancer patient | If they are willing, it would make the patient feel more helped and at peace. |

| Oncology physician | Praying with a patient if requested by the patient may be appropriate as a way of supporting the patient and providing comfort. | |

| Oncology nurse | For many individuals, spirituality is very important. For these patients offering spiritual support can make a great difference in how they respond to their treatment and diagnosis. | |

| Critical attitudes toward patient-practitioner prayer | Oncology nurse | I am a practitioner of medicine not spirituality. I can refer patients to spiritual advisors but would never personally pray with a patient, I personally do not feel that it is appropriate. And as an atheist, I do not feel that I offer any type of prayer with any credible level of sincerity. |

| Cancer patient | Religion is private. Treat [my] disease, not my soul. | |

| Oncology physician | Patient-initiated prayer would require faking, whereas a nurse offering prayer seems to be crossing professional boundaries. I would not take them out to dinner either. | |

| Positive attitudes toward patient-practitioner prayer | Cancer patient | It is appropriate because God is so important and powerful. God is a healer. It is important for the physician to know where I as the patient stand. I go home with God and they should know how I feel on the inside. If offered prayer, the patient can easily decline if they are not interested in receiving prayer. But another patient may be very interested in receiving that prayer. |

| Oncology physician | If praying provides the patient with comfort and the physician feels comfortable praying with the patient, it is a beneficial thing to do in keeping with a physician’s mission. | |

| Oncology nurse | As nurses our job is to provide comfort. If prayer is a way to do this then we should help the patient with prayer, even if we do not share the same beliefs. | |

| Potential negative consequences of patient-practitioner prayer | Oncology nurse | It may be appropriate. However, it needs to be clear that the oncologist visits are not primarily spiritual. If an oncologist privately chooses to pray for patients, that is completely appropriate. However, it seems that discussing it with a patient may cause awkwardness and deflect the focus from more important parts of the oncologist’s job. |

| Cancer patient | If they offered [prayer] I would think that I’m very sick. | |

| Oncology physician | I am personally not comfortable praying with patients. Offering prayer is lovely and from the heart, but I have an uncomfortable feeling that it is imposing beliefs that the patient might not share. Asking permission would be more appropriate, or praying only when the patient requests. | |

| Prayer alternatives | Cancer patient | It is fine for the physician to pray on his own without disclosing to the patient directly. |

| Oncology nurse | Even if the oncologist is not spiritual and/or religious, they can bow their head in respectful silence while the patient prays. If they are religious, they can join aloud or silently. If the provider is religious, it would be natural to offer a prayer for their patients in general or a specific patient, either privately or as part of a formal service, e.g., “prayers of the people” in the Anglican or Catholic tradition. | |

| Oncology physician | Religion is a personal matter. I am happy to support my patients in their views, but do not feel comfortable in participating in their practices with them. |

Table 5.

Qualitatively Assessed Theme and Subtheme Responses and Comparisons to the Appropriateness of Patient-Practitioner Prayer According to Advanced Cancer Patients, Oncology Physicians, and Nurses, n = 388a

| Themes and Subthemes | Advanced Cancer Patients (n = 69) | Oncology Physicians (n = 204) | Oncology Nurses (n = 115) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions for patient-practitioner prayer | 53 (77) | 144 (71) | 97 (84) |

| Awareness of patient’s spiritual background | 15 (22)b | 20 (10) | 28 (24)d |

| Concordance of religious/spiritual beliefs or practices | 12 (17) | 25 (12) | 13 (11) |

| Importance of an established patient-practitioner relationship | 12 (17) | 12 (6) | 7 (6) |

| Prayer is patient centered | 10 (14) | 11 (5) | 11 (10) |

| Appropriate context for prayer (e.g., patient facing death) | 10 (14) | 12 (6) | 17 (15) |

| Patient and/or practitioner feel comfortable | 9 (13) | 53 (26)c | 46 (40)d |

| Prayer initiated by patient | 8 (12) | 12 (6) | 17 (15) |

| Prayer initiated by practitioner | 8 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Practitioner feeling authentic or honest | 2 (3) | 50 (25)c | 25 (22)d |

| Potential benefits of patient-practitioner prayer | 27 (39) | 16 (8) | 20 (17) |

| Prayer can be a support for patients | 21 (30)b | 12 (6) | 16 (14) |

| Prayer can engender a better patient-practitioner connection | 9 (13) | 2 (<1) | 4 (1) |

| Critical attitudes regarding patient-practitioner prayer | 27 (39) | 55 (27) | 15 (13) |

| Prayer is beyond professional roles of physicians/nurses | 15 (22)b | 37 (18)c | 8 (7) |

| Religion/spirituality is private | 9 (13) | 17 (8) | 7 (6) |

| If requested, prayer is socially expected | 7 (10) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Positive attitudes regarding patient-practitioner prayer | 21 (30) | 14 (7) | 15 (13) |

| Prayer is intrinsically good and/or powerful | 12 (17) | 12 (6) | 12 (10) |

| Prayer is a part of holistic patient care | 11 (16) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Potential negative consequences of patient-practitioner prayer | 14 (20) | 49 (24) | 20 (17) |

| Prayer can cause relational misunderstandings | 8 (12) | 26 (13) | 8 (7) |

| Prayer can impose religious/spiritual beliefs | 5 (7) | 19 (9) | 10 (9) |

| Prayer can cause patient-practitioner relational boundary violations | 2 (3) | 12 (6) | 7 (6) |

| Alternatives to patient-practitioner prayer | 6 (9) | 40 (20) | 29 (25) |

| Offering private prayer or thoughts | 3 (4) | 25 (12) | 10 (9) |

| Offering a referral to pastoral care | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) | 7 (6) |

| Being respectful while declining prayer participation | 0 (0) | 15 (7) | 11 (10) |

| Other alternatives to prayer | 2 (3) | 2 (1) | 6 (5) |

Sample reduced from 391 because of missing data.

Top three subthemes cited by patients.

Top three subthemes cited by oncology physicians.

Top three subthemes cited by oncology nurses.

The “conditions for patient-practitioner prayer” theme was defined as the conditions required for prayer to be appropriate in the clinical setting. One physician exemplified this theme by stating, “It depends on the spirituality of the patient, the relationship between the patient and physician, and the comfort level of the physician.” Among patients, the most cited conditions were the practitioner knowing the patient’s spiritual background, the presence of a prior established patient-physician relationship, and concordance of patient and practitioner R/S beliefs. For example, one patient expressed feeling uncomfortable receiving prayer from a practitioner with potentially differing beliefs by emphatically stating “I don’t know who the person is praying to.” For physicians and nurses, the most frequently cited condition was the practitioner and/or patient feeling comfortable, a theme exemplified by a nurse: “I think it depends on the spirituality of the nurse and her comfort bringing this into care.”

The “potential benefits of patient-practitioner prayer” theme was defined as potential positive outcomes of patient-practitioner prayer. The most frequently raised subtheme was the potential for prayer to be a source of support for cancer patients, as illustrated by one patient: “Because I think prayer is as important a part of the treatment as conventional medicine itself. It is another way for doctors and nurses to hold out a hand.” Another view noted prayer can foster a better patient-practitioner relationship. One patient stated, “Because [prayer] would make me feel that they care for me to take time to pray. It shows that they are feeling people.” Similarly, one physician explained, “[Prayer] can’t hurt and it fosters closeness between doctor and patient.”

The “critical attitudes regarding patient-practitioner prayer” theme was defined as critical presuppositions underlying participants’ perceptions of patient-practitioner prayer. The most common subtheme for all groups was the view that prayer may violate professional boundaries. One patient explained, “The patient expects objectivity from the physician. To change that role would not be offensive but it would be a challenge to get used to. I have an image of a doctor I knew who would remove his stethoscope when talking to patients on a spiritual level.” One physician said, “Ideally there should be a division of labor between the physician and spiritual guide. The two strike me as separate roles and disciplines.” The next most common subtheme for all groups was that R/S are private matters. One nurse stated, “[I] want to keep my religious beliefs and practices private.”

The “positive attitudes regarding patient-practitioner prayer” theme was defined as positive presuppositions underlying respondents’ views of patient-practitioner prayer. The most common subtheme was that prayer is intrinsically good and/or powerful, as illustrated by one nurse who said, “To me a prayer is not about religion. It is a group of words which can bring about hope, meaning and peace to a person.” A second subtheme was the view that prayer is part of a holistic approach to patient care, illustrated by one patient who in explaining the appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer stated, “Doctors and nurses need to touch the patient where the patient is. This is important to healing.” Similarly, a physician stated, “While prayer is personal, it may be appropriate in the context of holistic healing.”

The “potential negative consequences of patient-practitioner prayer” theme was defined as possible deleterious outcomes of patient-practitioner prayer. Subthemes included the potential for patient-practitioner prayer to cause relational misunderstandings. This subtheme was illustrated by one physician who explained, “The physician might be seen as giving up on the medical/scientific approach.” Also raised were concerns regarding prayer causing an imposition of religious beliefs, as illustrated by one patient who stated, “You don’t want the patient to feel pressured by the doctor’s religiosity.” A third subtheme was the potential for prayer to cause boundary violations in the patient-practitioner relationship. One physician shared, “[Patient-practitioner prayer] depends on the oncologist’s comfort, beliefs and relationship with the patient. In some cases there is a boundary, in others there is not.”

The “prayer alternatives” theme was defined as alternatives to prayer considered potentially more appropriate than patient-practitioner prayer. Alternatives included showing respect without active participation in prayer, described by one nurse who shared, “I have stood respectfully in the room when prayers were offered of other faiths. If of my faith and the patient asked me to stay, I have said blessings of recovery.” Another alternative was private practitioner prayer. One physician described, “Private prayer is appropriate as a way to demonstrate caring for a patient. Sometimes I might pray for a patient without their knowledge just as a human being, which I think is always or almost always appropriate, but I am wary as an oncologist of taking a more formal, spiritual role.”

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the majority of patients, nurses, and physicians view patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate in the advanced cancer setting, and that most patients would find this practice spiritually supportive. Although viewed as less frequently appropriate than patient-initiated prayer, the majority of respondents viewed practitioner-initiated prayer as at least occasionally appropriate, a finding that stands in contrast to assertions that prayer should always be patient initiated.20,26 These findings are consistent with prior reports indicating that patient-practitioner prayer is more frequently considered appropriate in the setting of life-threatening illnesses when compared with other settings.5,11 Our study indicates that engagement of patient-practitioner prayer is best done, however, after considering key factors influencing the appropriateness of prayer in the clinical setting, indicated by six qualitatively derived themes.

First, optimal conditions for prayer should be appreciated, such as knowing the patients’ spiritual background, sharing concordance of beliefs, and weighing personal comfort and ability to be authentic. The noted conditions highlight the central role of taking a spiritual history,27 which provides cues to guide all subsequent spiritual care, including the appropriateness of prayer in the clinical setting. Factors found to quantitatively predict perceptions of the role of prayer in the clinical setting (e.g., Catholic religious tradition, increasing spirituality, gender) can also aid in informing the optimal context for patient-practitioner prayer.

Next, although practitioners should acknowledge that prayer is spiritually supportive for most patients, they also should weigh potential negative consequences, such as creating discomfort or distance with a patient who may not share the same belief system, may be uncomfortable with prayer in the medical setting, or may feel the clinician is imposing his or her R/S beliefs. Strategies to mitigate negative outcomes can be considered, such as ensuring concordance in R/S beliefs or offering prayer in a manner that provides comfortable ways to decline (e.g., simultaneously offering chaplaincy referrals).28 Beyond considering potential consequences, engagement in patient-practitioner prayer requires reflection by clinicians on their own and their patients’ underlying attitudes. For example, if practitioners feel that prayer is beyond their personal beliefs or professional roles, they should feel no obligation to participate in prayer. However, practitioners should weigh this view with the potential for prayer and other forms of spiritual care to benefit the patient and foster holistic care. Bringing these contrasting influences together, practitioners can offer spiritual care consistent with their own beliefs and professional commitments, such as calling on chaplaincy or remaining respectfully silent during patient prayer.29 Likewise, a practitioner who holds that patient-practitioner prayer is a part of holistic care must weigh this attitude against potential negative consequences. Beyond reflecting on underlying attitudes, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for countertransference and non–patient-centered motivations in the practice of patient-provider prayer,30 such as a clinician offering prayer in response to a personal emotion or agenda (e.g., to ease guilt over disease progression). The ability to prudentially consider potential consequences, underlying attitudes, personal emotions, and motivations regarding patient-practitioner prayer hinges on practitioners incorporating spiritual assessments as part of initial and ongoing care and being constructively aware of personal viewpoints, emotional responses to patients, and biases regarding R/S in the medical setting.

Finally, caregivers should consider prayer alternatives, such as offering private prayer or relying on other members of the health care team such as chaplains,31 while communicating respectful acknowledgment of patients’ R/S beliefs and practices even if declining participation.29 Patient-practitioner prayer involves some degree of shared experience of R/S and a shared willingness to invite that experience into the patient-practitioner relationship. Whether personal irreligiousness, deeply held R/S beliefs, or conviction that prayer is outside the practitioner’s role, a number of factors circumscribe the appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer. The frequent differences between patients and practitioners in regard to R/S characteristics, as noted in our sample and in others,32 only further highlight the importance of spiritual care approaches that sidestep potential conflicts associated with divergent beliefs and practices. Examples of such conflicts not only include a religious practitioner imposing R/S beliefs on a patient, but also can include an irreligious practitioner failing to acknowledge a patient’s R/S beliefs or issues, potentially disregarding existential needs1 and medically relevant information.33 Awareness and facility with other forms of spiritual care (e.g., taking a spiritual history) equips practitioners to navigate R/S on a case-by-case basis, recognizing that although the role of prayer should always remain voluntary, practitioners hold a central role as facilitators of spiritual care in the setting of advanced illness.21,27,31,34

Study limitations include the fact that respondents were surveyed from a single U.S. region. Given that this region has lower than national averages of religiosity, spirituality, and daily dependence on prayer,35 our study may underestimate the perceived appropriateness of patient-practitioner prayer and overestimate negative perceptions, although such characteristics may aid in conservatively informing the role of prayer in the medical setting. Last, the generalizability of these findings to other diseases or illness severities is unknown; further studies are required to define the role of patient-practitioner prayer in other settings.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the majority of patients, physicians, and nurses view patient-practitioner prayer as at least occasionally appropriate in the setting of advanced cancer. Furthermore, most patients view patient-practitioner prayer as spiritually supportive. Perceptions of prayer are shaped by key factors that inform its appropriateness on a case-by-case basis. These factors highlight the essential role of regular spiritual assessments by clinicians21,27 and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the provision of patient-centered spiritual care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award to Dr. Tracy Balboni.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have relationships with any entities having financial interest in this topic.

References

- 1.Alcorn SA, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig HG. Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:213–224. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199804)13:4<213::aid-gps755>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLean CD, Susi B, Phifer N, et al. Patient preference for physician discussion and practice of spirituality. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:38–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyama O, Koenig HG. Religious beliefs and practices in family medicine. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:431–435. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor EJ, Mamier I. Spiritual care nursing: what cancer patients and family caregivers want. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, et al. Discussing spirituality with patients: a rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:356–361. doi: 10.1370/afm.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Odell S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: psychiatrists’ and other physicians’ differing observations, interpretations, and clinical approaches. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1825–1831. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luckhaupt SE, Yi MS, Mueller CV, et al. Beliefs of primary care residents regarding spirituality and religion in clinical encounters with patients: a study at a midwestern U.S. teaching institution. Acad Med. 2005;80:560–570. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monroe MH, Bynum D, Susi B, et al. Primary care physician preferences regarding spiritual behavior in medical practice. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2751–2756. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curlin FA, Chin MH, Sellergren SA, Roach CJ, Lantos JD. The association of physicians’ religious characteristics with their attitudes and self-reported behaviors regarding religion and spirituality in the clinical encounter. Med Care. 2006;44:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207434.12450.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor EJ, Amenta M, Highfield M. Spiritual care practices of oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor EJ, Outlaw FH. Use of prayer among persons with cancer. Holist Nurs Pract. 2002;16:46–60. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King MO, Pettigrew AC, Reed FC. Complementary, alternative, integrative: have nurses kept pace with their clients? Medsurg Nurs. 1999;8:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. [Accessed March 1, 2010];Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10730-010-9128-3. Available from http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/Guidelines_Download.asp. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.World Health Organization. [Accessed May 15, 2009];Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness (IMAI) modules: palliative care: symptom management and end-of-life care. 2004 Available from http://www.who.int/3by5/publications/documents/en/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf.

- 18.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1913–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:578–583. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, Ciampa RC, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1803–1806. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pembroke NF. Appropriate spiritual care by physicians: a theological perspective. J Relig Health. 2008;47:549–559. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puchalski CM. Spirituality and end-of-life care: a time for listening and caring. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:289–294. doi: 10.1089/109662102753641287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koenig HG. Spirituality in patient care: Why, how, when, and what. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo B, Kates LW, Ruston D, et al. Responding to requests regarding prayer and religious ceremonies by patients near the end of life and their families. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:409–415. doi: 10.1089/109662103322144727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Josephson AM, Peteet JR. Handbook of spirituality and worldview in clinical practice. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handzo G, Koenig HG. Spiritual care: whose job is it anyway? South Med J. 2004;97:1242–1244. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146490.49723.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, Sellergren SA, Chin MH. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulmasy DP. Spirituality, religion, and clinical care. Chest. 2009;135:1634–1642. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. [Accessed March 1, 2010];US religious landscape survey. Available from http://religions.pewforum.org/maps.