Abstract

Objective

Based on the recognition that marrow contains progenitors for bone as well as blood, we undertook the first trial of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for a genetic disorder of bone, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). While we documented striking clinical benefit soon after transplantation, the measured level of osteopoietic engraftment was low. To improve the efficacy of BMT for bone disorders, we sought to gain insight into the cellular mechanism of engraftment of transplantable marrow osteoprogenitors.

Methods

We transplanted unfractionated bone marrow harvested from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-transgenic FVB/N mice into lethally irradiated FVB/N recipients. At 3 weeks post-transplantation, we assessed hematopoietic engraftment by flow cytometry and osteopoietic engraftment by immunohistochemical staining for the GFP protein.

Results

We show that the engraftment of transplantable marrow osteoprogenitors is saturable with a maximal engraftment of about 15% of all bone cells in the epiphysis and metaphysis of the femur at 3 weeks after transplantation. The number of engrafting sites is not up- or down-regulated in response to initial progenitor cell engraftment and there is no evidence for clonal succession of osteopoietic differentiation of engrafted progenitors.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the capacity for initial osteopoietic engraftment after BMT is limited and “megadose” stem cell transplantation is unlikely to enhance engraftment. Thus, novel strategies to foster osteopoietic chimerism must be developed.

Keywords: Osteopoiesis, Stem Cells, Bone Marrow Transplantation

Bone marrow is now universally recognized to contain both stem cells and committed progenitors capable of reconstituting hematopoiesis. Data from murine models, published over 40 years ago, proved that long term hematopoietic repopulating cells could be successfully transplanted by intravenous infusion[1] although the phenotype of the putative hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) had not yet been identified[2]. These successful animal studies supported the initial clinical trial of BMT[3]. Eleven years after the first human experience, BMT was shown to cure two children with immunodeficiency disorders[4, 5], which proved that human HSCs existed, the cells could be transplanted by intravenous infusion and BMT had the potential to cure human disease. The clinical utility of BMT has, in large part, driven our scientific quest to understand the biology of HSCs and our increasing knowledge of HSCs has, in turn, greatly contributed to the clinical advance of BMT.

More recently, we have recognized that bone marrow contains progenitors of bone as well as blood. Friedenstein et al. showed that spindle-shaped, plastic-adherent cells from bone marrow[6], now termed mesenchymal stem cells[7] or mesenchymal stromal cells[8] (MSCs), could give rise to bone and Long et al. showed that low density, nonadherent cells from marrow could differentiate to osteoblasts in vitro[9, 10]. Pereira et al. then demonstrated that murine marrow MSCs could engraft in bone after intravenous infusion[11, 12]. Although the immunophenotype of these marrow osteoprogenitors had not been completely identified, the preclinical data suggested that BMT may be used to transplant marrow osteoprogenitors for the treatment of bone disorders. To test this hypothesis, we undertook the first clinical trial of BMT for patients with a genetic disorder of bone, children with severe OI. In our pilot study, we demonstrated that marrow osteoprogenitors can engraft in bone giving rise to donor-derived osteoblasts, modify the microscopic structure of the bone, and promote clinical benefits for children with OI, suggesting a contribution to osteogenesis[13, 14]. Subsequent to our initial report, other investigators demonstrated that hypophosphatasia, another genetic disorder of bone, may also be treated with BMT[15, 16], independently validating our original findings.

While there is increasing enthusiasm for the use of marrow cell therapy for bone disorders, little is currently known about the transplantation biology of marrow osteoprogenitors. We[17] and others[18] demonstrated that nonadherent marrow cells are potent osteoprogenitors after intravenous transplantation. However, there are no studies addressing the mechanism of engraftment of this marrow osteoprogenitor. Here, we report that the marrow osteoprogenitor engrafts in discrete, finite and saturable sites within the marrow microenvironment. There may be heterogeneity among the engrafting sites, but the number of sites does not seem be up- or down-regulated in response to the initial progenitor cell engraftment. Finally, there is no evidence of clonal succession of osteopoietic differentiation of engrafted progenitors.

Methods

Transplantation

All animal studies were approved by the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Intuitional Animal Use and Care Committee. Bone marrow was harvested from transgenic mice (FVB/N genetic background) expressing the GFP under the control of the H2K promoter[19]. The unfractionated marrow cells were transplanted into 4-6 week old lethally irradiated (1125 cGy) FVB/N mice by tail vein injection approximately 4 hours after irradiation as previously described[17].

Immunohistochemical Staining and Analysis by Microscopy

The immunohistochemical staining of the bone sections and the microscopic evaluation of the metaphysis and epiphysis of femora were performed as previously described[17]. Three sections from each femur were evaluated and the average percentage of donor cells was used for that animal. Ten animals were evaluated in each experimental group except where indicated. Stained slides were examined on a Nikon E800 (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) with either a 40×/0.95 N.A. or a 60×/0.95 N.A. dry objective. Photomicrographs were acquired using the attached Nikon DXM1200 color camera and Nikon ACT-1 Version 2.11 software (Nikon). Images were cropped and labeled using Photoshop 7.0 and Illustrator 10.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

Blood or marrow cells were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with commercially available antibodies (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed with Cell Quest Pro Software, version 5.2.1 (BD Biosciences).

Curve Fitting and Statistical Analyses

GraphPad Prism, version 4, (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform the nonlinear regression analyses and curve fitting of the engraftment data. The raw engraftment data was fit to a first order association curve for a one-site engraftment model described by the equation, Y=Ymax (1-e(K*X)), where Y denotes the donor osteopoietic engraftment (percent of donor osteoblasts and osteocytes in the epiphysis and metaphysis), Ymax denotes the maximal donor osteopoietic engraftment, e is the base of the natural log function, K is the association constant, and X is the dose of transplanted marrow cells. In a separate analysis, the data was also fit to a two-site association curve described by the equation, Y=Y1max [X / (Kd1+X)] + Y2max [X / (Kd2+X)], where Y denotes the total donor osteopoietic engraftment, Y1max and Y2max denote the maximal donor osteopoietic engraftment in the engrafting sites 1 and 2, respectively, Kd1 and Kd2 are the association constants for sites 1 and 2, respectively, and X is the dose of transplanted marrow cells.

Finally, the engraftment data as a function of the log dose of transplanted marrow cells was fit to a sigmoidal dose response curve described by a four-parameter logistic equation:

where Y, Ymin, and Ymax denote the total, minimum, and maximum donor osteopoietic engraftment, respectively, LogK is the log of the dose of marrow cells that leads to half maximal engraftment, X is the log dose of marrow cells, and slope is the so-called “Hill slope”[20] indicating the slope of the curve at the point of half maximal engraftment.

For each nonlinear regression analysis, we quantify the goodness of fit, r2, to specify the proportion of variation in the observed osteopoietic engraftment that is due to the model. A value of 1.0 indicates an exact fit in of the data to the model so that all variation in the data is due to the model. By convention, r2 >0.80 is accepted to indicate that the data fits the model.

GraphPad Prism was also used to calculate the standard deviation of replicate experiments and to perform the Student's t-test to determine statistical significance of the difference of sample means. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Validation of Osteopoietic Engraftment Assay

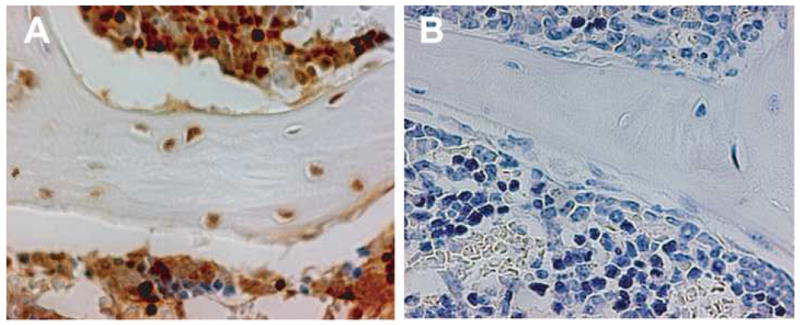

To determine the sensitivity and specificity of our immunohistochemical assay for donor (GFP+) cells, we analyzed histologic sections of femora from either GFP-transgenic mice (100% true positive) or wild-type mice (100% true negative). Using a standard protocol for all sections, we identified 93.4 ± 3.4% (mean ± standard deviation, n=10) of the bone cells within the epiphysis and metaphysis of transgenic femora as GFP positive (Fig. 1A), and only 0.3 ± 0.4% (n=10) of the bone cells in femora of wild-type mice (Fig. 1B). Thus, we consider the sensitivity of this assay to be 93% and the specificity to be >99%.

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical staining positive and negative controls.

Representative sections of femora obtained from (A) GFP-transgenic mice or (B) wild-type mice stained using our standard protocol. The GFP-expressing cells were visualized with NovaRed® and the sections were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. Original magnification 600×.

Effect of Cell Dose on Osteopoietic Engraftment

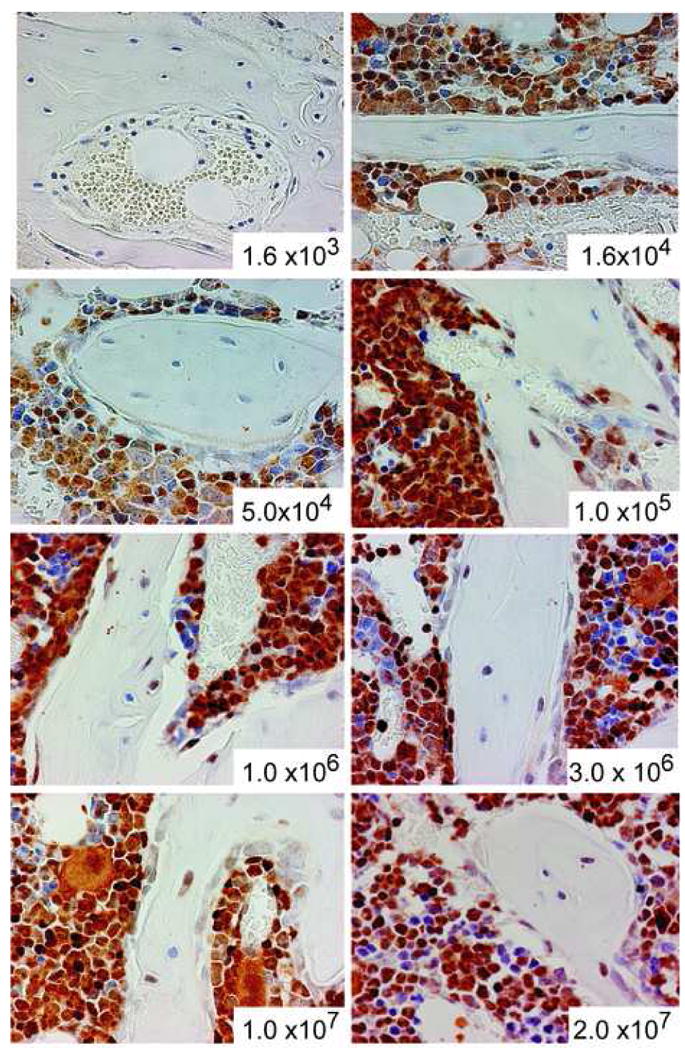

Graded doses of unfractionated bone marrow cells freshly harvested from a transgenic mouse were infused into lethally irradiated FVB/N mice by tail vein injection. At 3 weeks after transplantation, a time point we had previously determined to show high levels of both osteopoietic and hematopoietic engraftment, the mice were sacrificed and the formalin fixed, decalcified, paraffin embedded femora were analyzed by immunohistochemical staining for the GFP protein to assess donor cell engraftment (Fig. 2). The fraction of GFP-expressing bone cells (osteocytes and osteoblasts) of the epiphysis and metaphysis were determined as the donor osteopoietic chimerism.

Figure 2. Osteopoietic engraftment after BMT.

Immunohistochemical staining of bone marrow sections to identify donor (GFP+) bone and hematopoietic cells after transplantation of the indicated dose of unfractionated marrow cells. Original magnification 400×.

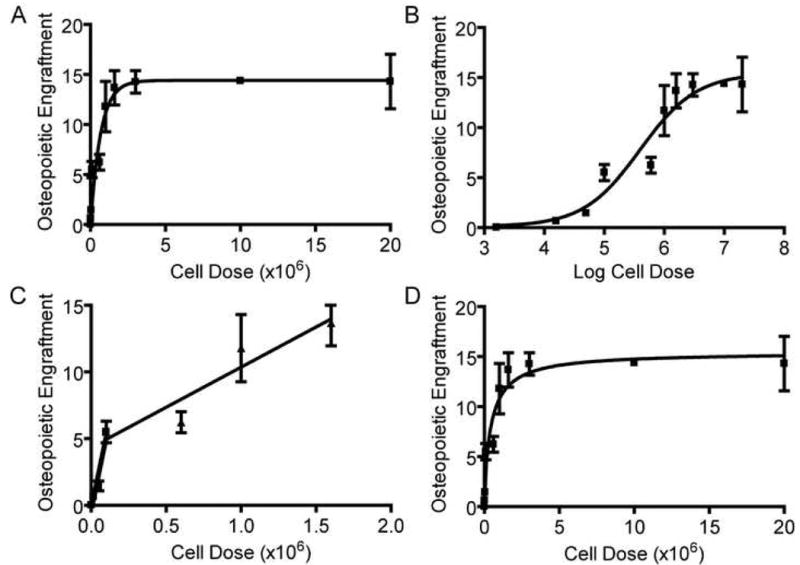

The magnitude of donor-derived bone cell engraftment can be described as a function of the transplanted marrow cell dose by a first order association curve (r2=0.96, Fig. 3A). Transplantation of doses from 1.6 × 103 to 1 × 106 cells resulted in a steep increase of the observed level of donor osteopoietic chimerism. At greater cell doses, the rise in the level of donor engraftment slowed and a plateau was established between 2 × 106 and 3 × 106 transplanted marrow cells indicating saturation of the host capacity for engraftment and differentiation of transplantable osteoprogenitors. A cell dose as high as 2 × 107, nearly 10-fold greater than the apparent maximum, did not increase osteopoietic engraftment confirming saturation of the host marrow microenvironment.

Figure 3. Effect of Cell Dose on Osteopoietic Engraftment.

(A) Nonlinear regression analysis of the osteopoietic engraftment after transplantation of increasing doses of unfractionated marrow cells to generate a first order association curve. Ten mice were studied for each cell dose except at 1.6 × 103 transplanted marrow cells in which 3 mice survived and were available for analysis. The displayed osteopoietic engraftment is the percentage of donor-derived osteocytes and osteoblasts in the metaphysis and epiphysis of the recipients' femora. (B) Nonlinear regression analysis of the same data as in (A) using a four parameter logistic equation (see Methods) to generate a sigmoidal dose-response curve. (C) Two linear regression analyses of osteopoietic engraftment after transplantation of 1.6 × 103 cells to 1.0 × 105 cells and after transplantation of 1.0 × 105 cells to 1.6 × 106 cells. (D) Nonlinear regression analysis of the same data as in (A) using a two-site binding model (see Methods).

Nonlinear regression analysis of the data according to the first order association curve indicates a maximum donor engraftment of 14.4% (95% confidence interval, 12.72-16.12%) of the bone cells. Half-maximal engraftment was achieved with the transplantation of 4.55 × 105 cells (95% confidence interval 3.11 to 8.42 × 105 ) and 95% saturation with an estimated 2 × 106 cells .

Nonlinear regression analysis using a four-parameter logistic equation (see Methods) generates a sigmoidal dose-response curve to fit our data (r2=0.98, Fig. 3B). This mathematical model also predicts a saturable phenomenon with a maximal engraftment of 15.27% (95% confidence interval, 11.65 to 18.69%) and half maximal engraftment at a dose of 3.81 × 105 cells (95% confidence interval, 1.35 × 105 to 1.01 × 106), consistent with the first order association model. The slope of the curve at the point of half-maximal engraftment, the so-called Hill slope[20], was 0.98 (95% confidence interval, 0.15 to 1.82) which is not significantly different than 1.0, indicating the lack of osteoprogenitor-osteoprogenitor interactions that would facilitate or hinder engraftment and differentiation of subsequent transplanted progenitors

A detailed analysis of the osteopoietic engraftment after transplantation of very low cell doses (1.6 × 103 to 5 × 104 cells) revealed a particularly steep gain compared to moderate cell doses (5 × 104 to 1.6 × 106) (Fig. 3C) indicating the possibility of two distinct osteoprogenitor cell-engrafting site interactions within the marrow microenvironment. Indeed, a two-site binding model aptly describes this data (r2=0.96, Fig. 3D). Using a two-site model, computer-generated nonlinear regression determines the total saturable engraftment to be 15.37% consistent with the previous models and predicts that the initial 2.0% osteopoietic engraftment was occupied by the sites with higher affinity or more robust differentiation capacity and the subsequent 13.37% was occupied by the lesser engraftment affinity/differentiation potential sites. The variability of observed engraftment using this assay precluded statistically distinguishing a one-site versus two-site model.

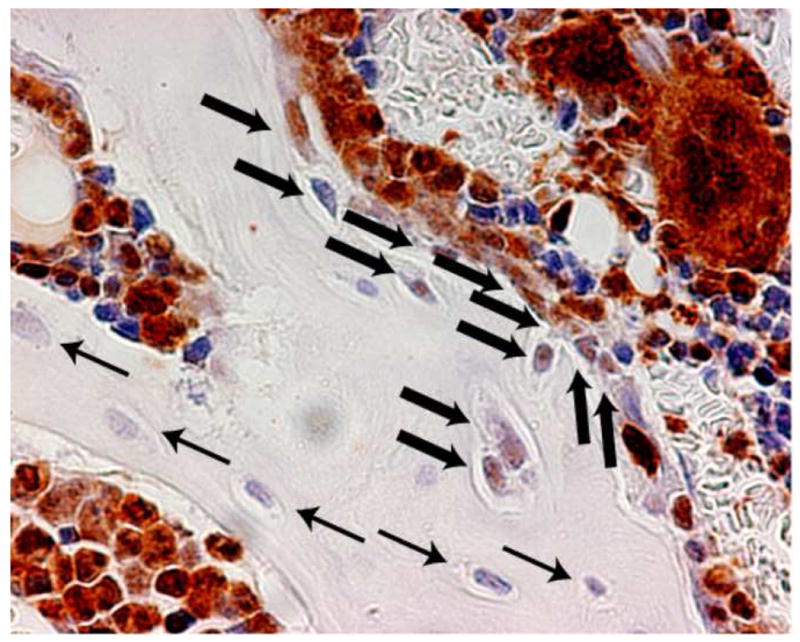

Histology of engraftment

Evaluation of the histologic sections of femora immunostained for GFP expression revealed a heterogeneous pattern of donor-derived cells. The average maximal donor osteopoietic chimerism determined by counting cells over the entire epiphysis and metaphysis was about 15% of the bone cells. However, some regions within the epiphysis and metaphysis contained over 50% donor-derived osteoblasts and osteocytes, while other regions lacked any donor cells (Fig. 4), consistent with our previous findings[17]. This pattern was observed at all doses of transplanted marrow cells

Figure 4. Histology of engrafted cells.

Immunohistochemical staining of bone section to identify donor (GFP+) bone cells. Donor-derived osteocytes and osteoblasts (thick arrows) and host cells (thin arrows) are indicated. Visualization with NovaRed® renders the donor cells a red-brown color. The section was counterstained with Harris hematoxylin imparting a blue color to host (GFP-) cells. Original magnification 400×.

Effect of Cell Dose on Hematopoietic Engraftment

All mice transplanted with ≥ 5 ×104 marrow cells reconstituted hematopoiesis (all lineages as determined by flow cytometry, data not shown) with >95% donor neutrophil chimerism at 3 weeks after BMT. In contrast, transplantation of 1.6 × 103 marrow cells did not reconstitute hematopoiesis in any mice (n=10) and transplantation of 1.6 × 104 marrow cells partially reconstituted in only 1 of 10 animals.

Donor osteopoietic engraftment after transplantation of 5 ×104 cells was 1.44% representing about a tenth of the maximal osteopoietic chimerism (Fig. 3); yet, this cell dose generated equally robust hematopoietic reconstitution at 3 weeks as marrow cell doses saturating osteopoiesis, e.g. 2 × 106 or 2 × 107 transplanted cells. These data indicate that relatively low marrow cell doses contain sufficient short term hematopoietic progenitors to reconstitute hematopoiesis but comparatively few osteoprogenitors suggesting that these repopulating activities are the domains of different cells within marrow. Moreover, short term hematopoiesis lacks a meaningful correlation with osteopoietic engraftment.

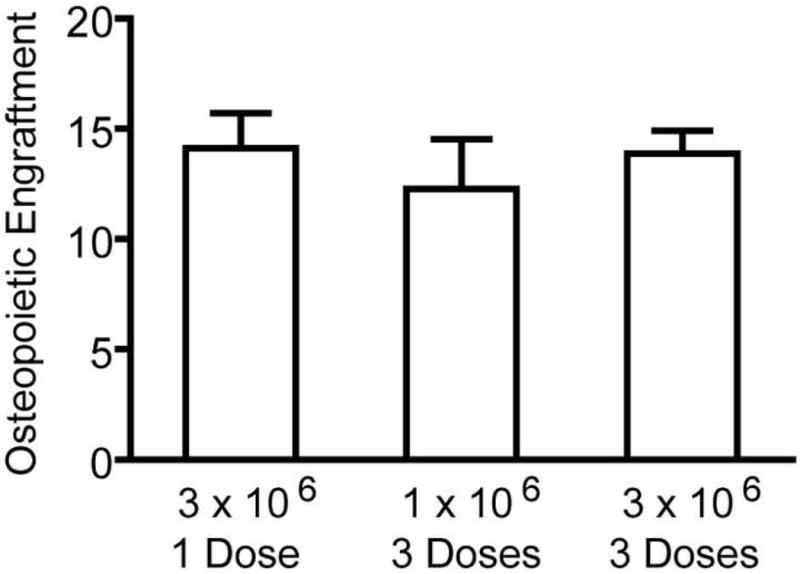

Regulation of the osteoprogenitor engraftment sites

Having demonstrated that transplanted marrow osteopoietic progenitors engraft in a finite number of sites within the host marrow microenvironment, we now wished to determine whether the number of sites were up- or down-regulated in response to the initial engraftment of progenitor cells (Fig. 5). First, we transplanted 3 × 106 marrow cells in a single dose, which is predicted to yield about 14% donor engraftment (see Fig. 3) and >90% saturation. We observed 14.12 ± 1.58% (n=5) donor bone cells consistent with our prediction. Then, we compared the outcome of transplanting 1 × 106 marrow cells per day on three consecutive days to provide the same total cell dose. The first daily dose of cells is predicted to yield about 11% donor engraftment and ∼70% saturation. We hypothesized that if the initial engraftment down-regulated the binding sites, then additional marrow cells would be unable to engraft. Indeed, we observed 12.27 ± 5.05% (n=5) donor bone cells, suggesting the possibility of down-regulation of available engrafting sites. However, the level of donor engraftment following the three daily doses is not statistically different from that after the single dose (P=0.46); hence such conclusions cannot be inferred from this data.

Figure 5. Osteoprogenitor-associated regulation of engraftment.

The bars represent the percentage of donor-derived bone cells (mean ± standard deviation, n=5) determined 3 weeks after transplantation. The quantity of unfractionated marrow cells per dose and the number of daily doses is indicated.

Second, we transplanted 3 × 106 marrow cells per day on three consecutive days to test the hypothesis that transplantation of near saturating doses may up-regulate the number of engrafting sites. This total cell dose of 9 × 106 marrow cells yielded 13.88 ± 2.31% (n=5) donor bone cells, which is not statistically different than the outcome of 3 × 106 marrow cells (14.12 ± 1.58%, n=5) (P=0.85) indicating the lack of up-regulation of the engraftment sites in response to osteoprogenitor cell engraftment.

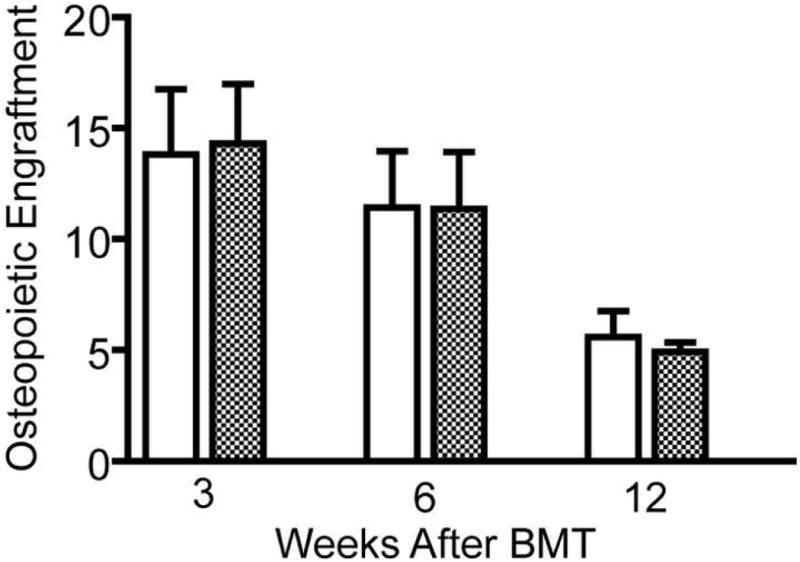

Active and Inactive Engraftment

Assessing osteoprogenitor engraftment and differentiation at 3 weeks after BMT precludes detection of engrafted progenitors that differentiate at later time points. Such sites within the microenvironment may provide a niche for engraftment, but remain undetected in our assay due to the lack of immediate differentiation. Such “inactive” sites, if they exist, would suggest that higher does of osteoprogenitors may provide a greater level of donor-derived osteopoiesis long term, although not immediately after transplantation. To test this hypothesis, we transplanted mice with 2 ×106 marrow cells to generate about 90% short term saturation (Fig. 3) and 2 × 107 cells, a 10-fold greater dose, to generate >99% short term saturation. Although we observed a decline in the measured level of donor-derived osteopoiesis over time, there was no difference in the osteopoietic chimerism between these two groups at 3, 6, and 12 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 6) suggesting that delayed differentiation of initially quiescent osteoprogenitors providing heightened long term donor-derived osteopoiesis does not occur within 3 months after transplantation.

Figure 6. Long-term osteopoietic engraftment of saturating doses of transplanted marrow cells.

The bars represent percentage of donor-derived bone cells (mean ± standard deviation, n=5) at 3, 6 and 12 weeks after transplantation of 2 × 106 (symbol) or 2 × 107 (symbol) marrow cells.

Discussion

The central hypothesis of our research is that long-term hematopoietic repopulating cells harbor inherent osteopoietic differentiation potential, which is only manifested under specific conditions. Experimental evidence to support the notion that plastic-nonadherent bone marrow cells are osteoprogenitors was originally reported by two independent research groups using in vivo transplantation studies[17, 18], supported by substantial in vitro data[21-25]. Our previously published data suggested that nonadherent marrow cells are more potent osteoprogenitors than MSCs, indeed the most potent transplantable marrow osteoprogenitor, after intravenous infusion. Moreover, we used retroviral vector insertion site analysis to demonstrate that at least some hematopoietic and osteopoietic cells share a common progenitor, or conceivably, a common stem cell[17]. This report extends our previous observation by providing the first data directed toward understanding the cellular mechanism by which the marrow osteoprogenitor engrafts in recipient bone. According to the dual osteopoietic-hematopoietic stem/progenitor hypothesis of Dominici et al., this work may have implications for the hematopoietic stem cell as well.

Interestingly, engraftment was saturable indicating that the osteoprogenitor engrafts in discrete, finite sites presumably at the endosteal surface of the bone since this is the anatomic location of osteoblasts, the precursor of osteocytes. Analysis of our data at low transplanted cell doses suggests two distinct engrafting interactions. Such an outcome could be the result of a homogeneous population of osteoprogenitors engrafting at two different sites within the marrow microenvironment. This notion is quite intriguing given that Dominici et al. showed that HSCs can give rise to bone[17] and Olmsted-Davis et al. showed that isolated side-population (SP) cells, a marrow subpopulation highly enriched for HSCs, robustly populate bone after systemic transplantation[18] suggesting that HSCs may represent a homogenous population of nonadherent osteoprogenitors engrafting in the marrow. Our data would then be the first evidence of heterogeneity among the stem/progenitor engrafting sites in the stem cell niche within the microenvironment. Alternatively, it is plausible that two different osteoprogenitor cells may engraft in a homogeneous population of engrafting sites. While multiple mesenchymal progenitors most assuredly exist, e.g., nonadherent cells and MSCs, there is no data to implicate a second population of nonadherent marrow cells capable of robust engraftment.

In principle, MSCs could engraft in the same niche as the nonadherent osteoprogenitors and the measured osteopoietic engraftment would be the sum of both nonadherent osteoprogenitors and MSCs. Such cellular heterogeneity may appear as a “two-site” binding process. However, our prior data suggests that systemically infused MSCs do not robustly engraft in bone. Doses as high as 2 × 106 MSCs/mouse typically generate less than 2% donor osteopoietic chimerism[17]. Unfractionated marrow over the range of doses presented in Fig. 3 are predicted to contain less than 200 MSCs/mouse infusion[26] and therefore, would not likely contribute a detectable level of donor-derived bone cells in this assay. Thus, if heterogeneity exists in the engraftment/differentiation process, we favor the hypothesis of heterogeneity of engraftment sites, but acknowledge the issue remains unresolved.

An important consideration in our analyses is that we are assaying osteopoietic differentiation, i.e., the fraction of donor-derived bone cells, as a function of transplanted marrow cell dose. The measured outcome is the result of two, related but separate, processes: (i) engraftment and (ii) differentiation. Cells with osteoprogenitor differentiation capacity could engraft but not promptly differentiate which would render the engraftment event undetectable in our study. If this cell differentiated at a later time, osteopoietic engraftment would be higher than measured. We sought to test this hypothesis, but found no evidence to support it (Fig. 6).

A highly relevant consequence of the two processes contributing to our measured outcome is that we cannot distinguish which is the rate limiting step conferring saturablity of the entire process, and which may underlie the possible heterogeneity among the engraftment interactions. The limiting factors or the source of disparity may reside in either the binding affinity between the stem/progenitor cell and the niche site or the capacity for osteopoietic differentiation of the stem/progenitor cell in that particular niche after engraftment. While the final outcome is indistinguishable in our study, these two concepts correspond to remarkably different cellular mechanisms.

We observed that 50,000 unfractionated marrow cells reconstituted hematopoiesis at 3 weeks after BMT, but minimally contributed to osteopoiesis. This data is consistent with a model in which short term hematopoietic repopulating cells lack robust osteopoietic differentiation potential. However, transplantation of 50,000 marrow cells can reconstitute hematopoiesis long term as well[27]. Conceivably, HSCs robustly repopulate hematopoiesis, possibly through extensive stem cell expansion after engraftment, while HSCs only give rise to bone at the site of engraftment. Another tenable explanation, albeit in the face of substantial data to the contrary, is that the long-term hematopoietic repopulating cell is not the principal transplantable osteoprogenitor. Future study is required to discern between these and other competing hypotheses.

Our studies did not provide evidence of “inactive” engrafting sites that may contribute to long term donor-derived osteopoiesis; however, our data did reveal a time dependent decrease in the level of donor osteopoietic chimerism. This time course of donor-derived osteopoiesis illustrates the need to develop novel strategies to improve the durability of the osteopoietic graft in an effort to further bone marrow cell therapies of bone disorders.

Our current data is consistent with our previous work suggesting that the there exists a dual osteopoietic-hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell. Further support of this concept rests in the observation that HSCs engraft at the endosteal surface in the marrow space[28-31]. However, we have never ascertained whether all HSCs give rise to both bone and blood. Four models offer cellular mechanisms that may explain all published data of hematopoietic-osteopoietic progenitor cells. First, the pool of HSCs is homogeneous, each with the capacity to differentiate to bone and blood and each HSC gives rise to bone upon engraftment. According to this hypothesis, osteopoietic differentiation is an index of HSC engraftment. Second, the pool of HSCs is not homogeneous; some HSCs have an inherent, genetically programmed differentiation capacity for both blood and bone, while others are genetically restricted to hematopoietic differentiation. According to this hypothesis, our measure underestimates the pool of engrafting HSCs. Third, HSCs may all have the inherent potential to give rise to bone, but differentiation is regulated by a stochastic mechanism. Finally, all HSCs engraft and have the potential to give rise to bone and blood, but environmental cues dictate whether osteopoietic differentiation ensues. Such cues may be chemical signals[32] or physical properties of the local tissue within microenvironment[33]. This latter hypothesis suggests that the supportive cells of the niche “talk” to the HSCs and govern their differentiation.

Ongoing studies are designed to further explore the mechanism of engraftment and differentiation of transplantable marrow osteoprogenitors as this understanding may lead to strategies to foster osteopoietic repopulation by donor-derived cells. Most importantly, future efforts will be designed to determine whether these cells meet the criteria of a stem cell as our previous data suggests, or should most accurately be designated a progenitor cell. Elucidation of the transplantation biology of marrow osteoprogenitors and engineering high levels of durable engraftment may offer new therapeutic avenues for diseases of the bone and the bone marrow niche.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Richard Ashmun and Ann Marie Hamilton-Easton for the flow cytometric analyses, Bobby Kirsh for assistance with the animal husbandry, Mike Straign for assistance with animal irradiation, and the Animal Histology Laboratory for preparation of the tissue sections. This work was supported in part by grants R01 HL077643, T32 CA070089, Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant P30 CA21765, the Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Till JE, McCulloch EA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Science. Vol. 241. New York, NY: 1988. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells; pp. 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Lu WC, Ferrebee JW. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195709122571102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach FH, Albertini RJ, Joo P, Anderson JL, Bortin MM. Bone-marrow transplantation in a patient with the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Lancet. 1968;2:1364–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)92672-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatti RA, Meuwissen HJ, Allen HD, Hong R, Good RA. Immunological reconstitution of sex-linked lymphopenic immunological deficiency. Lancet. 1968;2:1366–1369. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)92673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow.Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6:230–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz E, Le BK, Dominici M, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long MW, Robinson JA, Ashcraft EA, Mann KG. Regulation of human bone marrow-derived osteoprogenitor cells by osteogenic growth factors. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:881–887. doi: 10.1172/JCI117738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long MW, Williams JL, Mann KG. Expression of human bone-related proteins in the hematopoietic microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1387–1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI114852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira RF, Halford KW, O'Hara MD, et al. Cultured adherent cells from marrow can serve as long-lasting precursor cells for bone, cartilage, and lung in irradiated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4857–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira RF, O'Hara MD, Laptev AV, et al. Marrow stromal cells as a source of progenitor cells for nonhematopoietic tissues in transgenic mice with a phenotype of osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1142–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. NatMed. 1999;5:309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Gordon PL, et al. Clinical responses to bone marrow transplantation in children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Blood. 2001;97:1227–1231. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whyte MP, Kurtzberg J, McAlister WH, et al. Marrow cell transplantation for infantile hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:624–636. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahill RA, Jones OY, Klemperer M, et al. Replacement of recipient stromal/mesenchymal cells after bone marrow transplantation using bone fragments and cultured osteoblast-like cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominici M, Pritchard C, Garlits JE, Hofmann T, Persons DA, Horwitz EM. Hematopoietic cells and osteoblasts are derived from a common marrow progenitor after bone marrow transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11761–11766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404626101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olmsted-Davis EA, Gugala Z, Camargo F, et al. Primitive adult hematopoietic stem cells can function as osteoblast precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15877–15882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2632959100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominici M, Tadjali M, Kepes S, et al. Transgenic mice with pancellular enhanced green fluorescent protein expression in primitive hematopoietic cells and all blood cell progeny. Genesis. 2005;42:17–22. doi: 10.1002/gene.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill AV. The Combinations of Haemoglobin with Oxygen and with Carbon Monoxide. I. Biochem J. 1913;7:471–480. doi: 10.1042/bj0070471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito CY, Li CY, Bernstein A, Dick JE, Stanford WL. Hematopoietic stem cell and progenitor defects in Sca-1/Ly-6A null mice. Blood. 2003;101:517–523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonyadi M, Waldman SD, Liu D, Aubin JE, Grynpas MD, Stanford WL. Mesenchymal progenitor self-renewal deficiency leads to age-dependent osteoporosis in Sca-1/Ly-6A null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5840–5845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1036475100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lian JB, Balint E, Javed A, et al. Runx1/AML1 hematopoietic transcription factor contributes to skeletal development in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:301–311. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CZ, Li L, Li M, Lodish HF. The endoglin(positive) sca-1(positive) rhodamine(low) phenotype defines a near-homogeneous population of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2003;19:525–533. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CZ, Li M, De Graaf D, et al. Identification of endoglin as a functional marker that defines long- term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15468–15473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202614899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones EA, Kinsey SE, English A, et al. Isolation and characterization of bone marrow multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3349–3360. doi: 10.1002/art.10696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKinney-Freeman S, Goodell MA. Circulating hematopoietic stem cells do not efficiently home to bone marrow during homeostasis. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:868–876. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams GB, Chabner KT, Alley IR, et al. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin T, Li L. The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1195–1201. doi: 10.1172/JCI28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson SK, Haylock DN, Johnston HM, Occhiodoro T, Brown TJ, Simmons PJ. Hyaluronan is synthesized by primitive hemopoietic cells, participates in their lodgment at the endosteum following transplantation, and is involved in the regulation of their proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Blood. 2003;101:856–862. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taichman RS, Reilly MJ, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support human hematopoietic progenitor cells in in vitro bone marrow cultures. Blood. 1996;87:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]