Abstract

Objective

Transplantable osteoprogenitors as well as hematopoietic progenitors reside in bone marrow. We previously reported the first clinical trial of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for a genetic disorder of bone, osteogenesis imperfecta. Although the patients demonstrated striking clinical benefits after transplantation, measured osteopoietic engraftment was low and did not seem to be durable. Therefore, we sought an animal model, which closely reflects the clinical experience, to facilitate the development of strategies to improve the efficiency of osteoprogenitor engraftment after BMT.

Methods

We transplanted unfractionated bone marrow cells from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-transgenic mice into lethally irradiated recipients in four combinations of inbred mouse strains: from C57BL/6 into C57BL/6 (C-C), from C57BL/6 into FVB/N (C-F), from FVB/N into C57BL/6 (F-C) and from FVB/N into FVB/N (F-F). At 2 weeks after transplantation, we assessed donor hematopoietic and osteopoietic engraftment by flow cytometry, using a novel mean fluorescence assay, and by immunohistochemical staining for GFP.

Results

Hematopoietic reconstitution by donor cells was complete in all four combinations. While, osteopoietic engraftment of the transplanted cells was also documented in all the four groups, the magnitude of osteopoietic engraftment markedly differed among the strains where F-F > C-F > F-C> C-C.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the genetic background of inbred mouse strains affects the efficiency of osteopoietic engraftment after BMT. Thus, the murine strain must be considered when comparing experimental outcomes. Moreover, comparing the genetic variation among murine strains may lend insight into the factors governing osteopoietic differentiation of transplanted marrow cells.

Keywords: Bone marrow transplantation, bone, inbred strain of mice

Introduction

Bone marrow is comprised of a heterogeneous population of cells including the rare hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) that can give rise to committed hematopoietic progenitors maintaining all the lineages of the blood. When infused into lethally irradiated, genetically compatible allogeneic hosts, the HSC can reconstitute the entire hematopoietic system [1]. Indeed, bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is established clinical therapy for recalcitrant hematological malignancies and many nonmalignant hematologic disorders [2].

Over two decades ago, it was recognized that bone marrow contains progenitors of bone as well as blood, which have been designated mesenchymal stem cells or, more appropriately, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) [3]. Bone marrow MSCs are actually a heterogeneous population of cells but uniformly appear in vitro as spindle-shaped, plastic-adherent cells that express CD105 and CD73 [4]. Pereira et al. demonstrated that murine marrow-derived MSC could engraft in bone after intravenous systemic infusion [5, 6]. However, Long et al. showed that low-density, non-adherent cells from bone marrow could give rise to osteoblast in vitro [7] and more recent data suggests that marrow nonadherent cells are rather potent osteoprogenitors [8]. Although the marrow-derived osteoblast progenitor cells had not been completely characterized, the compelling laboratory data encouraged us to investigate whether transplantation of unfractionated bone marrow, including both the putative osteoprogenitors and the HSCs, could be employed for the treatment of bone disorders. We reported the first clinical trial of BMT for children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a genetic bone disorder in which generalized osteopenia leads to bony deformities, excessive bone fragility with painful fractures and short stature. In our study, we showed that marrow-derived osteoblast progenitor cells could engraft in bone and give rise to osteoblasts which were associated with improvements in the microscopic structure of the bone as well as clinical benefits for the patients [9, 10]. Subsequent to our report, investigators treated other genetic bone diseases with BMT and confirmed our findings that the donor osteoblast progenitor cells are functional in patients after transplantation [11, 12].

The clinical utility of BMT may be greatly expanded as we gain a greater understanding of the biology of bone marrow cells. However, the transplantation biology and differentiation potential of bone marrow cells has not yet been fully elucidated and animal models continue to be indispensable tools in laboratory studies. Mice are ideal models for BMT research, however, many different inbred strains are used in similar studies [13, 14]. Although the cells from different strains of mice are generally thought to be similar, several studies have demonstrated that the variation of strains could affect the properties of the transplanted cells and target tissues suggesting that results of biologic and preclinical studies in mice may be significantly affected by the particular murine model [15, 16].

Here, we report, the affect of the genetic background of two inbred strains of mice on the hematopoietic and osteopoietic engraftment of donor cells after BMT. Both the donor stem cells and the host microenvironment were evaluated as both may significantly alter experimental outcomes. We focused our efforts on FVB/N and C57BL/6 mice as these two strains are frequently used in studies of osteopoietic and hematopoietic biology, respectively. Moreover, these strains are often used to establish transgenic mouse models amplifying the importance of recognizing the influence of the inbred genetic background for engraftment and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow cells were harvested from transgenic FVB/N (H2Kq) or C57BL (H2Kb) mice expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the H2K promoter [17]. CD3-expressing cells were depleted from the harvested marrow cells using the AutoMACS® magnetic cell sorting system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) with PE conjugated anti-CD3e antibody (clone 145-2C11, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-PE Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturers instructions. The CD3-depletion reduced the CD3 content from 2–3% of nucleated cells in freshly harvested marrow to undetectable levels (<0.1%). Then, 3 × 106 CD3-depleted marrow cells were transplanted into 6- to 8-week-old lethally irradiated (1125 cGy) wild-type FVB/N or C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) by tail vein injection approximately 24 hours after the irradiation, as previously described [8]. At 2 weeks after BMT, mice were euthanized and the blood, bone marrow and the hind limbs were obtained for analysis. A minimum of five animals was used in each experimental group. All animal studies were approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Intuitional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Immunohistochemical staining and analysis by microscopy

Immunohistochemical staining of the bone sections and microscopic evaluation of the metaphysis and epiphysis of femora were performed as described previously [8]. Briefly, formalin-fixed, decalcified, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with rabbit anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (1:300; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), using a goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). After incubation with Vectastain ABC (Vector Laboratories), color development was performed with NovaRED (Vector Laboratories). All slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific Company L.L.C., Middletown, VA, USA). Three stained sections from each femur were examined by at least 2 investigators on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with either a 10×/0.25NA or a 40×/0.6NA dry objective. Photomicrographs were acquired with the attached AxioCam HR color camera and AxioVision 4.5 SP1 software (Carl Zeiss).

Osteoblast isolation and culture

Osteoblast cultures were established as previously described [18]. Briefly, marrow-depleted bones were cut into progressively smaller fragments with surgical scissors. After extensive mincing into conical glass vials (REACTI VIALS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), bone fragments were digested for 120 minutes at 37°C with collagenase P (0.2 mg/mL; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium-Ham’s F12 mixture (DMEM/F12, Mediatech. Inc., Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech). After several washes with DMEM/F12, the digested bone chips were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50μM L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. The medium was changed twice a week.

Flow cytometry

Blood, bone marrow cells and cultured-osteoblasts were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) with commercially available antibodies (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with CellQuest Pro software, version 5.2.1 (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software version 7.5 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Complete blood count (CBC)

Peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus. Complete blood counts were performed using a HEMAVET 950FS hematology analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc., Waterbury, CT, USA).

Growth profiles

Osteoblasts (1×105) derived from wild type and transgenic mice of each strain were cultured in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50μM L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. The number of osteoblasts was assessed by directly counting the cells using a hemocytometer on day 3, day7, day 10 and day 14.

Statistical analysis

All statistical data are presented as mean±SEM. Statistical analyses were performed by a two-tailed Student’s t test with the Excel 2003 program (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or Prism, Version 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). A minimum of 5 replicates was analyzed for each experiment. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Hematopoietic reconstitution

CD3-depleted bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 or FVB/N GFP-expressing transgenic mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice (C-C and F-C, respectively) and into FVB/N mice (C-F and F-F, respectively). All bone marrow cell grafts were depleted of CD3-expressing cells which eliminated murine graft versus host disease (GVHD) which could bias our data. To evaluate hematopoietic reconstitution of donor cells, we analyzed the fraction of GFP-expressing cells in harvested peripheral blood at 2 weeks after bone marrow transplantation, a time point at which we previously observed the greatest engraftment of donor-derived osteoblasts [13]. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the donor hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells engrafted and gave rise to all the lineages in peripheral blood at this early time point (Fig. 1A).

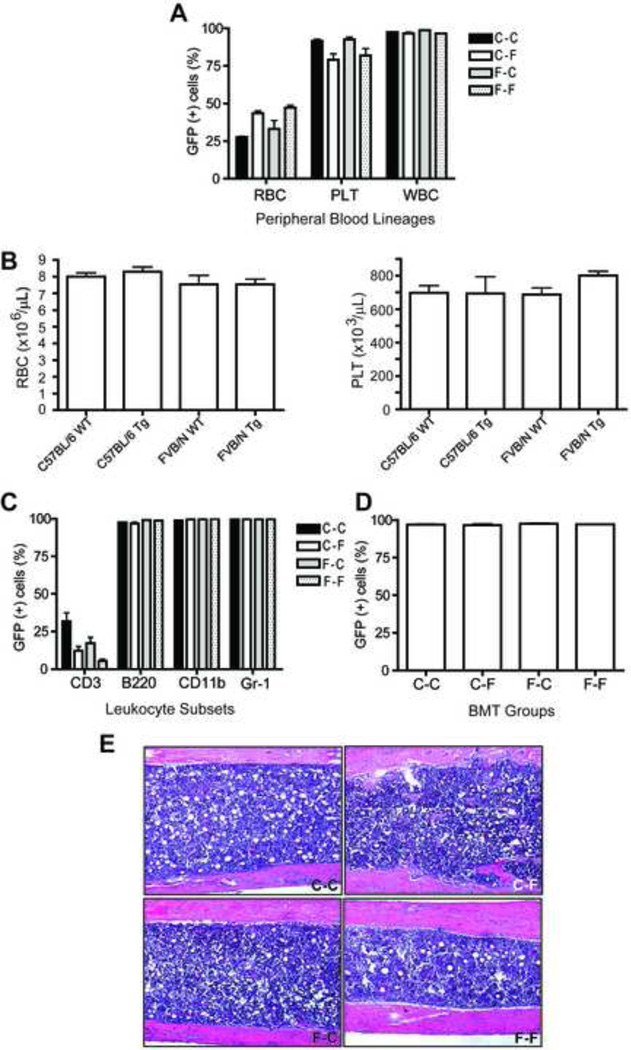

Figure 1.

Donor cell engraftment in peripheral blood and bone marrow. (A) The bars represent the percentage of GFP-expressing cells (mean ± SEM, n=5) measured by flow cytometry (A) 2 weeks after BMT in peripheral blood lineages, and (B) The number of RBC (left) and PLT (right) from complete blood counts of the parent strains of mice. Flow cytometry as in panel (A) analyzing (C) leukocyte subsets, and (D) bone marrow. (E) Representative H&E stained histologic sections of bone from each of the four transplantation groups demonstrating overall cellularity (x100). RBC, erythrocytes; PLT, platelets, WBC, leukocytes. Antigen (CD) designations in (C) indicate the leukocyte subset identified by that antigen expression. C-C, GFP-C57BL/6 cells transplanted into C57BL/6 mice; C-F, GFP-C57BL/6 cells transplanted into FVB/N mice; F-C, GFP-FVB/N cells transplanted into C57BL/6 mice; F-F, GFP-FVB/N cells transplanted into FVB/N mice. See text for details.

Interestingly, when FVB/N mice were recipients (C-F and F-F) regardless of the strain of donor marrow, the erythrocytes of the peripheral blood were 45.4±1.2% GFP+ (donor) which was significantly higher than when C57BL/6 mice were recipients (C-C and F-C) (30.0±2.5%; n= 10 per group, p<0.001) (Fig. 1A). In transplantation groups in which C57BL/6 mice were recipients (C-C and F-C), the platelet chimerism was significantly higher than when FVB/N mice were recipients (C-F and F-F) (92.7±0.8% vs. 80.6±2.9%; n= 10, p=0.001) (Fig 1A). The parent strains do not exhibit significant differences in the homeostatic erythrocyte or platelet cell counts (Fig 1B).

There was no significant difference between the groups in the chimerism of total leukocytes or the leukocyte subsets (Fig. 1A and C). Donor contribution to the CD3-expressing cell compartment was substantially less than the other subsets, as expected, since the two-week analysis is an insufficient interval for reconstitution of T cells. Consistent with the other leukocyte subsets, there was no difference in the T-cell chimerism between the four groups.

Flow cytometric analysis of the bone marrow revealed equivalent donor-derived hematopoietic reconstitution among the four groups (C-C: 97.1±0.4%, C-F: 96.6±0.9%, F-C: 97.6±0.5% and F-F: 97.2±0.2%; p=NS) (Fig 1D). Microscopic examination of histologic sections revealed approximately 90% cellularity of the femoral marrow space in all groups (Fig. 1E).

Flow cytometric analysis of osteopoietic engraftment

At two weeks after bone marrow transplantation, osteoblasts were isolated from harvested bones from mice in each of the four groups. Cells were then expanded in tissue culture to obtain an adequate sample for analysis. In addition to the experimental bones, osteoblasts were isolated from wild type and GFP-transgenic mice, as negative and positive controls, respectively, of both C57BL/6 and FVB/N strains.

One of the barriers to flow cytometric analysis of mesenchymal cells such as osteoblasts is the substantial autofluorescence exhibited by these cells. Using wild type bone marrow mononuclear cells to set a negative gate, marrow cells from GFP-transgenic mice (both strains) exhibit >98% positivity. In contrast, if positive and negative gates are set between osteoblasts from wild type and GFP-transgenic mice, wild-type osteoblasts became 3.61% GFP false positive and GFP-transgenic osteoblasts became 88.2% GFP positive (about 12% false negative) (Fig 2A). These false positive and false negative rates indicate that flow cytometry of these highly autofluorescent cells using a standard gating strategy lacks sufficient specificity to measure low levels (generally less than 10%) of osteopoietic engraftment typically observed.

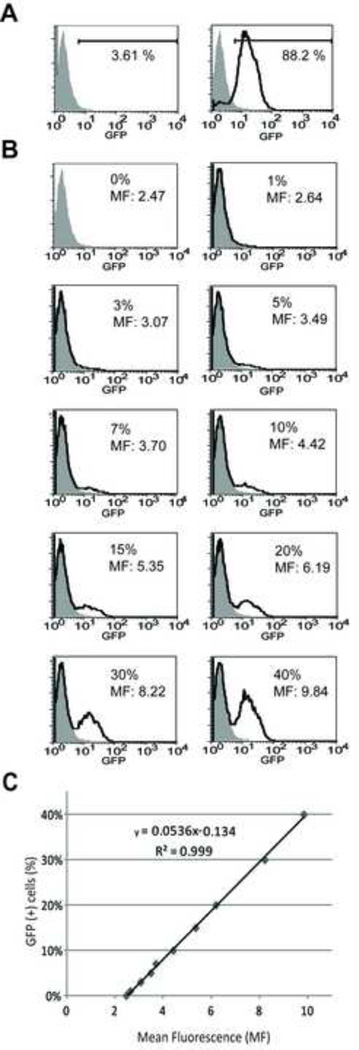

Figure 2.

Analysis of culture-expanded osteoblasts by flow cytometry. (A) Representative histograms of GFP expression in osteoblasts isolated from wild-type (shaded curve, left panel) and GFP-transgenic (solid line, left panel) mice. The gate indicates the fraction of GFP-expressing cells in each analysis. (B) Histograms of GFP expression among standard cell suspensions of GFP-transgenic and wild-type osteoblasts. The percentage of GFP-transgenic osteoblasts in the suspension and the measured mean fluorescence (MF) of the entire sample is indicated. Wild-type osteoblasts (shaded curve); mixed cell suspension (solid line). (C) Regression analysis of the mean fluorescence and the percentage of GFP-expressing cells in each of the standard cell suspensions.

To overcome this limitation, we investigated the use of mean fluorescence of the entire population of culture-expanded osteoblasts as a measure of the fraction of GFP-expressing (donor) cells. We first prepared standards containing 1%, 3%, 5%, 7%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30% and 40% GFP-expressing osteoblasts in suspension with wild-type osteoblasts. Then, the mean fluorescence of each cell preparation was measured and correlated with the known fraction of GFP-expressing cells (Fig 2B). Regression analysis of the resulting data revealed a highly linear relationship (r2 =0.999) allowing us to calculate the donor chimerism among culture-expanded osteoblasts after BMT from the measured mean fluorescence (Fig 2C). To exclude potential variations in autofluorescence due to strain differences, standard curves were generated from each of the murine strain combinations to be analyzed.

GFP-transgenic FVB/N donors transplanted into wild-type FVB/N recipients (F-F) showed 7.7±0.5% GFP+ cells which was significantly greater osteopoietic engraftment than in the F-C (3.7±1.5%, p<0.05), C-F (3.5±0.6%, p<0.001), and C-C (0.1±0.1%, p<0.001) groups. The least engraftment was observed in the GFP-transgenic C57/BL6 donors transplanted into C57/BL6 recipients (C-C), which was significantly less than in C-F (p=0.002) and F-C (p=0.03) groups. There was no significant difference between the C-F and F-C groups (Fig. 3). These data indicated that the genetic background of the FVB/N strain confers greater osteopoietic engraftment after bone marrow transplantation. The advantage rests in the biology of both the donor marrow cells and the recipient microenvironment. In contrast, the genetic makeup of C57/BL6 allows the least engraftment. However, the apparent disadvantage the C57BL/6 genetic background can be partially overcome by using either FVB/N marrow cells or microenvironment.

Figure 3.

Donor-derived osteopoietic cells in isolated osteoblasts. Bars represent the fraction of GFP-expressing cells (mean ± SEM) among culture-expanded osteoblasts obtained from recipient bone 2 weeks after transplantation (n=5). BMT groups are defined as in Fig. 1.

Histological analysis of osteopoietic engraftment

To further assess the osteopoietic engraftment after bone marrow transplantation, histologic sections of bone were immunostained for GFP expression as a marker of donor origin (Fig 4A). The relatively large, cuboidal cells, often showing abundant cytoplasm and eccentrically placed nuclei, distributed along the endosteal surface were considered to be osteoblasts, while solitary, stellate-shaped cells within the lacunae of bone were regarded as osteocytes as we published previously [8]. Analysis of the fraction of GFP-expressing osteoblasts and osteocytes in the epiphysis and metaphysis demonstrated that the donor-derived osteoblast engraftment in the F-F (40.0±12.8%) group was significant higher than in the C-C group (6.5±1.4%; n=5 per group, p=0.018) (Fig.4B). The engraftment in the C-C group was significantly lower than in the other groups as well (Fig. 4A). There was no statistically significant difference between the other three groups.

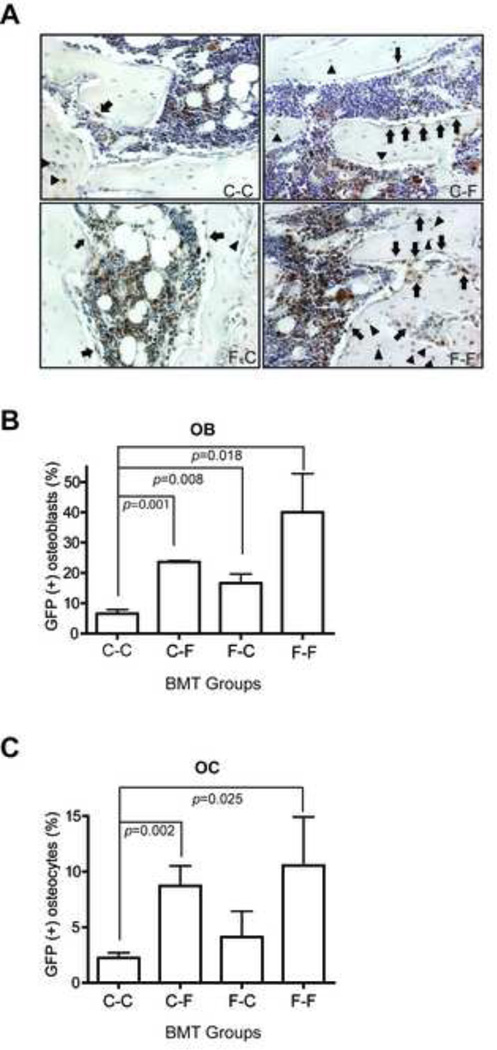

Figure 4.

Analysis of osteopoietic engraftment by immuohistochemical staining. (A) Representative photomicrographs of bone sections taken from mice 2 weeks after BMT from each of the four BMT groups stained with anti-GFP (red) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). The GFP-expressing osteoblasts (arrows) and osteocytes (arrow heads) are indicated (x200). (B) Bars indicate the fraction of GFP-expressing osteoblasts (mean±SEM, n=5) determined by microscopic evaluation of bone sections stained as in (A). (C) The fraction of GFP-expressing osteocytes (mean±SEM, n=5) determined as in (B). BMT transplant groups are as defined in Fig. 1.

The analysis of osteocyte engraftment showed a trend similar to the osteoblast engraftment (Fig. 4C). The F-F group showed the greatest engraftment (10.6±4.4%), which was significantly more than in the C-C group (2.2±0.5%; n=5 per group, p=0.025). Similarly, the C-F group had significantly more osteocyte engraftment than the C-C group (8.7±1.8% vs. 2.2±0.5%, p=0.002) (Fig. 4C). There were no statically significant differences between the other three groups.

Visual inspection of the histologic section revealed that donor-derived osteoblasts and osteocytes were found in clusters in all four groups, similar to our previous report [13]. While the number of clusters seemed to be similar among the groups, greater total donor osteopoietic chimerism was the result of substantially more GFP-expressing cells within each cluster.

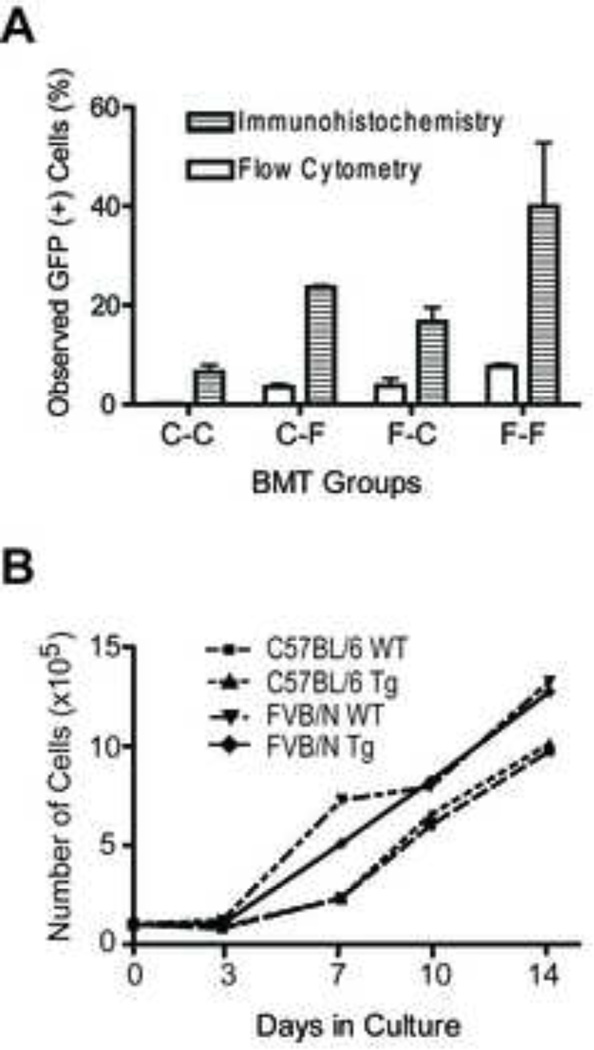

Comparison of methods to determine osteopoietic engraftment

A direct comparison of the two analytical techniques in our study, flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, reveal a general qualitative agreement. Strikingly, however, the quantitative outcome of immunohistochemical staining for GFP expression and microscopic accounting of the GFP+ osteoblasts consistently indicated about 5-fold more donor derived cells than measured with flow cytometric analysis for GFP expression among culture-expanded osteoblasts (Fig 5A). While osteoblasts from FVB/N mice seem to proliferate more rapidly in culture compared to C57/BL6 derived osteoblasts, wild type cells and those derived from transgenic animals proliferate equally for each strain (Fig 5B). Similarly, mean cellular GFP fluorescence of transgenic osteoblasts decreases over 10 passages of culture: however, the fluorescence is stable between 2 and 4 passages (data not shown). All analyses in our study were performed on passage 3 cells. Thus, neither technical consideration can account for the different outcomes of our two analytic approaches.

Figure 5.

Comparison of flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry determination of donor-derived osteopoiesis. (A) Bars represent the measured fraction of GFP-expressing osteoblasts (mean ± SEM, n=5 per group) of culture-expanded cells by flow cytometry (open column) versus osteoblasts in situ by immunohistochemical staining (striped column). BMT transplant groups are as defined in Fig. 1. (B) Growth profiles of culture-expanded osteoblasts derived from wild type and transgenic mice of each strain.

Discussion

Laboratory investigations using transgenic mouse models are indispensable tools in the development cell therapy protocols. After the initial clinical trials, refinement of the therapeutic strategies often exploits the same murine systems used to launch the original trials. Both FVB/N and C57BL/6 inbred strains of mice are frequently used to establish transgenic models because they can produce many high-quality embryos and often attain a superovulation in response to hormone injections [15]. While FVB/N mice are often used in mesenchymal studies, C57BL/6 mice are most commonly used for hematopoietic studies. For our transplantation studies focused on both mesenchymal cells, such as osteoblasts and MSCs, as well as hematopoietic cells, the optimal murine model has not been clearly defined. Therefore, in this study, we examined the effect of mouse strains on the hematopoietic and osteopoietic engraftment of donor cells after bone marrow transplantation.

We previously reported that the greatest engraftment of donor osteopoietic cells after bone marrow transplantation with FVB/N mice was obtained at 2 weeks after transplantation of ≥3×106 donor bone marrow cells and decreases rapidly thereafter; thus, the magnitude of engraftment observed in this study was consistent with our prior studies [13, 19]. In an effort to assess the initial engraftment potential, then, we transplanted 3×106 CD3-depleted bone marrow cells from FVB/N or C57BL/6 GFPtransgenic mice into either lethally irradiated FVB/N or C57BL/6 wild-type recipients followed by the analysis of hematopoietic and osteopoietic engraftment at 2 weeks after transplantation. FACS analysis demonstrated that donor cells could successfully engraft in peripheral blood and bone marrow in any of the strain combinations. Interestingly, the analysis of short-term hematopoietic reconstitution in these mouse strains suggested a difference in the differentiation and proliferation in the erythrocyte and megakaryocyte lineages, but not in the leukocytes. The fraction of donor-derived erythrocytes was statistically greater when FVB/N mice were recipients and the fraction of donor-derived platelets when C57/BL6 mice were recipients. In both cases, the donor strain was inconsequential. Since the parent strains do not exhibit differences in homeostatic erythrocyte or platelet cell counts, this unexpected observation suggests the marrow microenvironment of these two strains vary in their supportive capacity for engraftment and/or differentiation hematopoietic progenitors with FVB/N demonstrating a greater propensity for erythropoiesis and C57/BL6 favoring thrombopoiesis.

The collective body of data presented here indicates that transplanting marrow cells into the FVB/N strain generates greater osteopoietic engraftment, compared to the C57/BL6 strain, and suggests that specific genetic factors may regulate osteopoietic differentiation of transplanted marrow cells. Moreover, comparing the genetic variation among murine strains may lend insight into these factors which potentially could be targeted to enhance bone marrow cell therapy of bone. For example, the clustering of GFP-expressing cells in bone suggests that a single osteoprogenitor engrafts at a given site and then transiently proliferates and differentiates to form this donor-derived cell constellation [13]. Our data showing similar numbers of clusters, but more donor cells per cluster in the FVB/N mice, suggests that the two strains have a similar capacity for engrafting osteoprogenitors, but FVB/N cells have a greater mesenchymal proliferative potential which may be due to the engrafting cells and/or the microenvironment. The bone turnover rate is not likely to play a role since osteopoietic engraftment occurs early after TBI/BMT [13], a time point when with very limited bone turnover. Whether differing bone responses to radiation underlie the greater osteopoietic proliferative potential is unknown. Indeed, the genetic factors regulating the response to radiation injury may be a fruitful arena for investigation.

Phinney et al. examined the properties of bone marrow stromal cells from several different mouse strains [15]. They reported that FVB/N mice have a significantly greater number of colony forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-F) than C57BL/6 mice. Furthermore they demonstrated that adherent marrow stromal cells from FVB/N mice expressed significantly higher levels of alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme induced during the early phases of osteoblast differentiation, than C57BL/6 cells. Additionally, several investigators have reported genetic variability in the cortical thickness, density and mineral content of bones from different strains of mice. Especially revealing is that C57BL/6 mice have lower bone density due to the lower number of osteoblasts and decreased bone formation [20, 21]. Our current findings suggest that osteoblast progenitors in bone marrow from FVB/N mice have higher capacity to and differentiate into osteoblasts after bone marrow transplantation. Further, the FVB/N marrow seems to be more suitable to receive and retain donor-derived osteoblast progenitor cells. Thus the published data of others is in accord with our data suggesting that that FVB/N bone marrow may contain more osteoblast progenitor cells, or perhaps the microenvironment is more supportive of osteoprogenitor differentiation.

Autofluorescence of culture-expanded osteoblasts and MSCs is one of the major barriers to the use of flow cytometry to quantitate donor cells demarcated by GFP expression [22, 23]. Additionally, the observed GFP-generated fluorescence in cells seems to diminish with prolonged culture expansion, possible due to down regulation of GFP transgene expression, further reducing the difference between cell fluorescence peaks of GFP-expressing donor cells and highly autofluorescent host cells [24]. This problem is amplified when assessing relatively low levels of engraftment, which is common in mesenchymal engraftment studies and illustrated in our current data. In such cases, our novel protocol using the mean fluorescence of the entire cell population in contrast to defining positive and negative gates, allows for a consistent method of assessing the fraction of GFP-expressing cells among culture-expanded osteoblasts or MSCs. This approach may become critically important for reliably assessing very low levels of donor-derived cells.

One area of concern is that immunohistochemistry of bone sections and microscopic evaluation and enumeration of GFP+ cells consistently indicated about 5-fold more donor-derived osteoblasts than determined by flow cytometric analysis. Flow cytometry determines the fraction of GFP+ cells within the population of culture-expanded osteoblasts. Only mitotically active osteoblasts are evident; osteoblasts that are not capable of cell division and all osteocytes will not be included. In contrast, microscopic evaluation of histologic sections immunostained for GFP reveals all donor-derived (GFP+) cells within the limits of sensitivity and specificity of the staining protocol. Thus, less GFP+ cells are present in the cultured osteoblasts than reside in the bone. At the early time point of analysis in this study (2 weeks), most donor-derived bone cells are osteoblasts [13]. However, at later time points, when most donor-derived bone cells will be osteocytes, the discrepancy may become far more significant. We suggest that immunohistochemical staining for GFP-expression is the ideal analysis to determine donor osteopoietic engraftment; however, if the analysis of culture-expanded cells is essential, such analyses are valid recognizing that the determination of engraftment is underestimating, possibly to a substantial extent, the magnitude of donor osteopoiesis.

The principal outcome of this study was the demonstration that the FVB/N strain generates grater osteopoietic engraftment, compared to the C57/BL6 strain, after transplantation of CD3-depleted bone marrow and may constitute a superior model for investigations of BMT targeting bone disorders. Nonetheless, C57/BL6 mice do exhibit donor-derived osteopoiesis after BMT and therefore, seem to be acceptable models if an experimental design requires the use of these mice. Our findings may explain differing results obtained from individual labs that utilize similar experimental designs but use different strains of mice. The selection of mouse strains will be very important regarding the outcome of experiments with bone marrow transplantation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Alan Flake for provision of the flow cytometry. This work was supported in part by grant R01 HL077643 and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chen BP, Galy A, Kyoizumi S, et al. Engraftment of human hematopoietic precursor cells with secondary transfer potential in SCID-hu mice. Blood. 1994;84:2497–2505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira RF, Halford KW, O'Hara MD, et al. Cultured adherent cells from marrow can serve as long-lasting precursor cells for bone, cartilage, and lung in irradiated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4857–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira RF, O'Hara MD, Laptev AV, et al. Marrow stromal cells as a source of progenitor cells for nonhematopoietic tissues in transgenic mice with a phenotype of osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1142–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long MW, Williams JL, Mann KG. Expression of human bone-related proteins in the hematopoietic microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1387–1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI114852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominici M, Pritchard C, Garlits JE, Hofmann TJ, Persons DA, Horwitz EM. Hematopoietic cells and osteoblasts are derived from a common marrow progenitor after bone marrow transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11761–11766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404626101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5:309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Gordon PL, et al. Clinical responses to bone marrow transplantation in children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Blood. 2001;97:1227–1231. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driessen GJ, Gerritsen EJ, Fischer A, et al. Long-term outcome of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in autosomal recessive osteopetrosis: an EBMT report. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:657–663. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whyte MP, Kurtzberg J, McAlister WH, et al. Marrow cell transplantation for infantile hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:624–636. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominici M, Marino R, Rasini V, et al. Donor cell-derived osteopoiesis originates from a self-renewing stem cell with a limited regenerative contribution after transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:4386–4391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Liu Y, Kalajzic Z, Jiang X, Rowe DW. Heterogeneity of engrafted bone-lining cells after systemic and local transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:3650–3657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phinney DG, Kopen G, Isaacson RL, Prockop DJ. Plastic adherent stromal cells from the bone marrow of commonly used strains of inbred mice: variations in yield, growth, and differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 1999;72:570–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace JM, Golcuk K, Morris MD, Kohn DH. Inbred strain-specific response to biglycan deficiency in the cortical bone of C57BL6/129 and C3H/He mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1002–1012. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominici M, Tadjali M, Kepes S, et al. Transgenic mice with pancellular enhanced green fluorescent protein expression in primitive hematopoietic cells and all blood cell progeny. Genesis. 2005;42:17–22. doi: 10.1002/gene.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominici M, Rasini V, Bussolari R, et al. Restoration and reversible expansion of the osteoblastic hematopoietic stem cell niche after marrow radioablation. Blood. 2009;114:2333–2343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marino R, Martinez C, Boyd K, Dominici M, Hofmann TJ, Horwitz EM. Transplantable marrow osteoprogenitors engraft in discrete saturable sites in the marrow microenvironment. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beamer WG, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Baylink DJ. Genetic variability in adult bone density among inbred strains of mice. Bone. 1996;18:397–403. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimai HP, Linkhart TA, Linkhart SG, et al. Alkaline phosphatase levels and osteoprogenitor cell numbers suggest bone formation may contribute to peak bone density differences between two inbred strains of mice. Bone. 1998;22:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gay CV, Lloyd QP, Gilman VR. Characteristics and culture of osteoblasts derived from avian long bone. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1994;30A:379–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02634358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lechner A, Schutze N, Siggelkow H, Seufert J, Jakob F. The immediate early gene product hCYR61 localizes to the secretory pathway in human osteoblasts. Bone. 2000;27:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vroemen M, Weidner N, Blesch A. Loss of gene expression in lentivirus- and retrovirus-transduced neural progenitor cells is correlated to migration and differentiation in the adult spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]