Abstract

We have identified a rare small (∼450 kb unique sequence) recurrent deletion in a previously linked attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) locus at 2q21.1 in five unrelated families with developmental delay (DD)/intellectual disability (ID), ADHD, epilepsy and other neurobehavioral abnormalities from 17 035 samples referred for clinical chromosomal microarray analysis. Additionally, a DECIPHER (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk) patient 2311 was found to have the same deletion and presented with aggressive behavior. The deletion was not found in either six control groups consisting of 13 999 healthy individuals or in the DGV database. We have also identified reciprocal duplications in five unrelated families with autism, developmental delay (DD), seizures and ADHD. This genomic region is flanked by large, complex low-copy repeats (LCRs) with directly oriented subunits of ∼109 kb in size that have 97.7% DNA sequence identity. We sequenced the deletion breakpoints within the directly oriented paralogous subunits of the flanking LCR clusters, demonstrating non-allelic homologous recombination as a mechanism of formation. The rearranged segment harbors five genes: GPR148, FAM123C, ARHGEF4, FAM168B and PLEKHB2. Expression of ARHGEF4 (Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 4) is restricted to the brain and may regulate the actin cytoskeletal network, cell morphology and migration, and neuronal function. GPR148 encodes a G-protein-coupled receptor protein expressed in the brain and testes. We suggest that small rare recurrent deletion of 2q21.1 is pathogenic for DD/ID, ADHD, epilepsy and other neurobehavioral abnormalities and, because of its small size, low frequency and more severe phenotype might have been missed in other previous genome-wide screening studies using single-nucleotide polymorphism analyses.

INTRODUCTION

Several low-copy repeat (LCR)-rich regions in the human genome have been associated with common well-known recurrent microdeletion and reciprocal microduplication syndromes caused by non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) also known as genomic disorders (1,2). Some of these genomic disorders manifest variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric phenotypes, e.g. deletions and duplications in 1q21.1 (3,4), 10q11.21q11.23 (5), 15q11.2 (6), 15q13.3 (7,8), 16p11.2 (9,10), 16p12.1 (11) and 16p13.11 (12).

Several rare copy-number variations (CNVs) have been identified in up to 8% of patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and some of these CNVs contain genes important in psychological and neurological functions (13–16). A subset of the identified loci have been found previously in patients with other neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric phenotypes such as autism and schizophrenia, e.g. recurrent CNVs in 1q21.1, 15q11.2, 15q13.3, 16p11.2 and 16p13.11 (14,16), as well as CNVs encompassing the ASTN2, CNTN5, GABRG1 (16), A2BP1, AUTS2, CNTNAP2 and IMMP2L (13) genes. Importantly, several new candidate susceptibility genes: GRM5 and PTPRD (13), BCHE, PLEKHB1, NDUFAF2, SLC2A3 and NPY (15), CPLX2, ZBBX and PTPRN2 (16) and BDNF (17) have been reported. Recently, CNVs involving glutamate receptor gene networks (GRM1, GRM5, GRM7 and GRM8) have been reported in patients with ADHD (18).

Since conventional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) had not yielded any statistically significant loci (19–21), meta-analyses of family-based and case–control GWA screenings in patients with ADHD have been performed (22–25). However, no significant associations have been found, likely because the effects of the individual risk variants are very small and include multiple rare alleles. A number of candidate genes playing a role in the dopamine and serotonin pathways have been identified, including SLC6A3 [dopamine transporter gene (DAT1)], DRD4 (dopamine receptor 4 gene), DRD5 (dopamine receptor 5 gene), HTR1B (serotonin receptor gene) and SNAP25 (26–32). The SLC9A9 (solute carrier family 9, member 9, sodium/hydrogen exchanger) gene has also been implicated using association studies (19,33–36). Recently, integration of the various GWAS results has identified a list of 85 ADHD candidate genes, 45 of which defined a neurodevelopmental protein network involved in directed neurite outgrowth (37).

Here, using clinical array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis, we have identified a small (450 kb unique sequence) rare recurrent deletion and reciprocal duplication in 2q21.1, including brain-specific ARHGEF4 and GPR148, in 10 unrelated families with DD/intellectual disability (ID), ADHD, autism and epilepsy.

RESULTS

aCGH analysis

We have detected four ∼417–631 kb (patients 1–4) and one ∼1.2 Mb (patient 5) (450 kb unique sequence) microdeletions flanked by large complex LCR clusters on chromosome 2 at 2q21.1q21.2, proximal LCR2q21.1 (∼800 kb, chr2:130,394,886–131,193,978) and distal LCR2q21.1q21.2 (∼1.2 Mb, chr2:131,646,166–132,838,104) (hg18) (Figs 1 and 2A and B) using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) V8.0 OLIGO (patients 2 and 4) and V8.1 OLIGO (patients 1, 3 and 5). The deletion coordinates are chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 (patients 1–4) and chr2:131,204,290–132,356,498 (patient 5). Patient 5 also has a 390 kb duplication in 17p13.3 (chr17:2,942,086–3,331,777), involving the ASPA gene. Both CNV's were inherited from an apparently healthy mother. Mutations in ASPA are associated with Canavan's disease (OMIM: #271900), which is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait (38,39). The 17p13.3 duplication involves only a 5′ portion of the ASPA gene and thus, is rather unlikely to be deleterious. In addition, patient 5 does not manifest features of Canavan's disease.

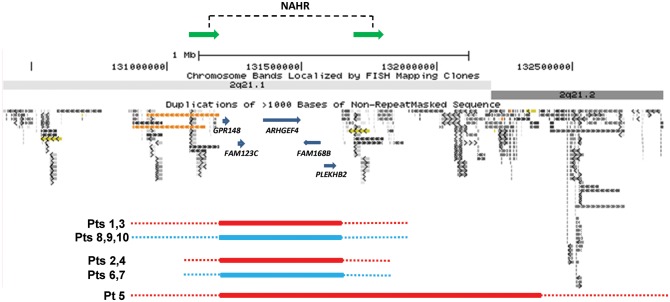

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic architecture in 2q21.1. Genomic coordinates correspond to the hg18 build of the human genome. Red bars represent deletions and blue bars represent reciprocal duplications. The NAHR sites identified in patient 2 mapped to directly oriented ∼109 kb subunits, shown as green horizontal arrows.

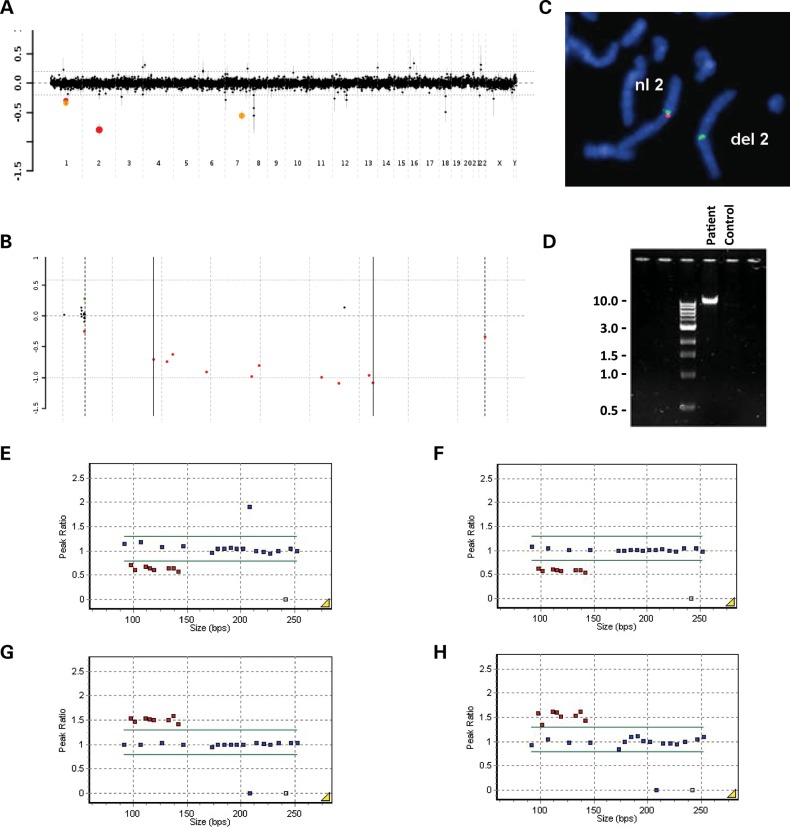

Figure 2.

Chromosomal microarray, FISH, MLPA and PCR results. (A) Genome-wide and (B) 2q21.1 aCGH plots showing the identified deletion in patient 2. Probes are arranged on the x-axis according to physical mapping positions, with the most proximal 2q21.1 probes to the left and the most distal 2q21.1 probes to the right. Values along the y-axis represent log2 ratios of patient: control intensities. (C) Partial metaphase chromosomes after FISH with a 2q21.1-specific BAC clone RP11-675I14 (red) and a control chromosome 2 alpha satellite centromere probe (green), showing the absence of red signal on the deleted chromosome 2 in patient 2. (D) Agarose electrophoresis gel showing patient 2-specific junction fragment (∼ 10 kb) and absence of patient-specific junction fragment in control DNA. MLPA analysis plots confirming the 2q21.1 deletion in patients (E) 1 and (F) 2, and the reciprocal duplication in patients (G) 8 and (H) 10.

CMA in patient 5's maternal grandparents did not show any evidence of the deletion and duplication, thus they most likely arose in his mother de novo. The fact that patient 5 inherited the 2q21.1 deletion from his apparently healthy mother could be explained by sex differences in expressivity or paternally inherited or de novo changes in the modifier gene(s). Using CMA, patient 3's brother and mother have also been found to carry the 2q21.1 deletion.

Additionally, we have identified five patients with reciprocal duplications at 2q21.1 using CMA V8.0 OLIGO (patients 6 and 7) and V8.1 OLIGO (patients 8–10) (Fig. 1). The duplication coordinates are chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552. All nine of patient 9's siblings were tested by CMA; only one had the 2q21.1 duplication.

Copy-number verification by fluorescence in situ hybridization and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analyses

Deletions in patients 3, 4 and 5 and parents of patient 5 were verified by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis with the chromosome 2q21.1-specific BAC clone RP11-675I14 (Fig. 2C). The 17p13.3 duplication in patient 5 was verified with the BAC clone RP11-64J4. Duplications in patients 6, 7 and 9 were verified with the BAC clone RP11-581I23. In patients 7 and 9, the 2q21.1 duplications were found to be inherited from their fathers. Inheritance of the 2q21.1 duplications in patients 6, 8 and 10 is not known.

The 2q21.1 deletions in patients 1 and 2 and 2q21.1 duplications in patients 8 and 10 were verified by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (Fig. 2E–H).

Bioinformatics and in silico sequence analysis

Bioinformatic analyses of the 2q21.1 deletion-flanking LCRs, including the Miropeats program, revealed two directly oriented paralogous subunits ∼109 kb in size and of 97.7% overall DNA sequence identity that can serve as a potential substrate for NAHR (chr2:131,084,465–131,193,978 and chr2:131,691,307–131,800,522) (Figs 1 and 3).

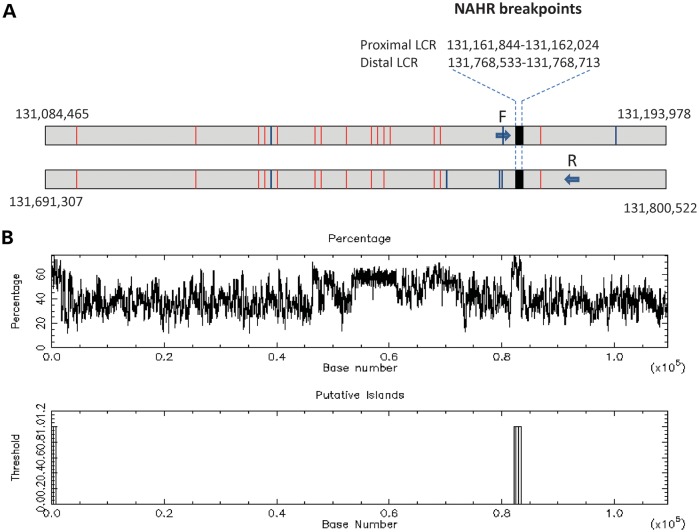

Figure 3.

DNA sequence homology between the proximal LCR2q21.1 (chr2:130,394,886–131,193,978) and distal LCR2q21.1q21.2 (chr2:131,646,166–132,838,104) clusters for paralogous subunits larger than 1 kb in size (hg18). (Top) UCSC segdup track representing the proximal LCR2q21.1 cluster. (Middle) Results of Miropeats program analysis between the proximal LCR2q21.1 and distal LCR2q21.1q21.2 clusters. (Bottom) UCSC seg dup track representing the distal LCR2q21.1q21.2 cluster.

We have identified 15 and 13 7-mer CCTCCCT and 3 and 4 degenerate 13-mer CCNCCNTNNCCNC recombination motifs known to be associated with hotspots for homologous recombination crossover sites (40), in the directly oriented proximal and distal ∼109 kb subunits, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Genomic structure of the ∼109 kb LCR2q21.1 subunits of 97.7% DNA sequence identity, in which NAHR sites were mapped in patient 2. (A) The NAHR site regions in patient 2 were narrowed to a 181 bp interval by sequencing the long-range PCR products obtained with the forward primer F specific to the proximal subunit and the reverse primer R, specific to the distal subunit (arrows depicting primers are not shown to scale). (B) Schematic representation of the GC content of the ∼109 kb LCR2q21.1 subunits with NAHR sites mapping to over 60% GC-rich fragment.

Long-range polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing

Using long-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers F: 5′-TGTGCATGTTTACACTAATCTCCTGTCTGA, specific to the proximal ∼109 kb subunit LCR2q21.1 and R: 5′-ACCAATGTCATATCAGCCCACAGTATTTGCTA, specific to the distal paralogous copy within LCR2q21.1q21.2, we have obtained a patient-specific junction fragment in patient 2 (Fig. 2D). To locate potential NAHR sites within the LCRs, we sequenced the patient-specific junction fragment PCR product. Sequence analysis revealed NAHR sites within a 181 bp GC-rich interval between two informative cis-morphic nucleotides chr2:131,161,844–131,162,024 and chr2:131,768,533–131,768,713 in the proximal and distal LCR subunits, respectively (Fig. 4B and C). Both the proximal and distal NAHR sites align in AluSq SINE repeats.

We did not identify the NAHR sites in patients 1, 3 and 4 because of insufficient numbers of cis-morphisms that precluded the primer design for the remaining portion of the ∼109 kb LCR subunits. The non-recurrent deletion in patient 5 was likely not mediated by NAHR, given the absence of directly oriented LCR subunits in LCR2q21.1q21.2 (Fig. 1).

Deletion and duplication frequency in affected and control populations

We have identified a total number of five 2q21.1 deletions and five reciprocal duplications from 17 035 patients, including those with ADHD (∼2.5%), autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) (∼9.2%), epilepsy (∼5.5%) and DD/ID (∼28.0%). The percentage of cases with no indications is 17.0%. The presence of DD/ID in all our patients may reflect an ascertainment bias, because individuals are often referred for CMA for general indications such as ID/DD.

We have compared the frequency of the 2q21.1 deletion (between 131.19 and 131.65 Mb) among our study population to the frequency in 14 000 controls to determine whether it predisposes individuals to an abnormal phenotype. No 2q21.1 deletions have been found in five control groups consisting of 2792 individuals (41) (British origin, Affymetrix GeneChip 500 K Mapping array), 2493 individuals (42) [Worldwide and European descent, Illumina 317K arrays, Illumina 550 + 317 K supplemented with 240S single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays, Illumina 650Y arrays], 1152 individuals (43) (Caucasian, African American, Asian and Hispanic origin, Affymetrix GeneChip 100 and 500 K arrays), 450 individuals (44) (African, Asian and European descent, Agilent 105 K arrays) and 5088 individuals in dbGaP. There was only one case of an 828 kb overlapping deletion (chr2:131,316,199–132,144,820) identified in an additional fifth control group consisting of 2025 individuals (45) (Caucasian, African American and Asian Americans, Illumina Infinium II HumanHap550 BeadChip), who was later re-evaluated as affected and thus, inappropriate for inclusion in an ‘unaffected control’ group (H. Hakonarson, personal communication). In addition, there was no 2q21.1 deletion or duplication in the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/).

No 2q21.1 duplications were found in four control groups consisting of 6120 individuals (42–45). There was only one case of a 367.6 kb duplication (chr2:131,262,791–131,630,364) identified in the control group consisting of 2792 individuals (41).

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that small rare recurrent deletions in 2q21.1 are pathogenic for DD/ID, ADHD, epilepsy and other neurobehavioral abnormalities. In support of this notion, a DECIPHER (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk) patient 2311 presenting with aggressive behavior was found to have the same deletion. Interestingly, the chromosome 2q21.1 region has been identified previously as linked in patients diagnosed with ADHD using an endophenotype approach for linkage analysis (46). However, this 2q21.1 deletion has not been found in larger-sized genome-wide CNV studies in 335 (13), 366 + 825(14), 99 (15), 248 (16) and 1013 (18) individuals with ADHD. Given the small size (450 kb) of the unique sequence between the flanking LCRs of the 2q21.1 deletion region, low frequency and a more severe phenotype than isolated ADHD, it is possible that patients with this deletion might have been missed (or not included) in the aforementioned studies. For instance, the study performed by Williams et al. (14) using SNP arrays analyzed only CNVs >500 kb in size.

We have also identified five individuals with reciprocal duplications involving of 2q21.1. Given the parental data and the fact that the 2q21.1 duplication was present in an apparently healthy individual (41), we have concluded that the clinical consequences of the 2q21.1 duplication are unknown at this time and more patients need to be studied for better genotype–phenotype correlations.

The rearranged region in our patient cohort includes five RefSeq genes: GPR148, FAM123C, ARHGEF4, FAM168B and PLEKHB2. ARHGEF4 (Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 4; also called ASEF) is expressed only in the brain and has been proposed to regulate the actin cytoskeletal network, cell morphology and migration, and neuronal function (47). The family of Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors has been implicated in neural morphogenesis and connectivity, regulating the activity of small Rho GTPases by catalyzing the exchange of bound GDP by GTP (48). Defects in guanine nucleotide exchange factor genes are known to contribute to a number of disease conditions such as: slowed nerve conduction velocity (ARHGEF10, MIM 608236), X-linked mental retardation (ARHGEF6, MIM 300436), early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (ARHGEF9, MIM 300607), Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 4H (FGD4 MIM 609311), coronary heart disease (KALRN, MIM 608901), faciogenital dysplasia with ADHD (FGD1, MIM 305400) and breast cancer (ARHGEF5, MIM 114480). Given that expression of ARHGEF4 is restricted to the brain and defects in guanine nucleotide exchange factor genes have been implicated in a number of neurological diseases, including ADHD, we suggest that ARHGEF4 is a good candidate gene for neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioral disorders.

GPR148 encodes a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR) protein and its expression is restricted to the brain and testes (49). GPRs contain extracellular N terminus, seven transmembrane regions, and an intracellular C terminus and transduce extracellular signals through heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins, G-proteins. To date, a couple of genes encoding GPRs have been shown to be pathogenic in humans. GPR56 is responsible for bilateral frontoparietal polymicrogyria (MIM 606854) and GPR98 is responsible for familial febrile seizures (MIM 604352) and Usher syndrome type IIC (MIM 605472). In addition, GPR85 has been shown to be involved in determining brain size, modulating diverse behaviors and potentially in vulnerability to schizophrenia (50) and haploinsufficiency of GPR63 was postulated to play a role in the etiology of the ASD (51).

Studies in mice revealed expression of Fam123c in the central and peripheral nervous system, suggesting an involvement in murine neurogenesis (52). However, the function of this gene in humans is unclear at this time. Similarly, very little is known about PLEKHB2 (Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family B member 2) (53) and FAM168B. However, it is interesting to note that Lesch et al. (15) reported an ∼500 kb duplication in 11q13.4, harboring the brain-specific PLEKHB1 gene expressed in primary sensory neurons, in two siblings with ADHD, who inherited the CNV from their affected mother.

The proximal chromosome 2 region 2q11.2q21.1 is LCR-rich. Homozygous LCR-flanked recurrent microdeletions involving NPHP1 in 2q13 have been reported in patients with familial juvenile nephronophthisis 1 (NPHP1, OMIM 256100). The more distally adjacent segment in 2q13 encompasses a 1.71 Mb recurrent microdeletion associated with ID and dysmorphism (54) and chromosome region 2q13q14.1 harbors the evolutionary breakpoint of the ancestral centric fusion of two chromosomes in non-human primates (55). Bioinformatic analyses of the 2q21.1 flanking large and complex LCR clusters revealed ∼ 109 kb directly oriented paralogous LCR subunit pair that can serve as substrates for NAHR. In patient 2, we identified NAHR sites in a GC-rich portion of these LCRs (Fig. 4). Interestingly, polypurine and pyrimidine sequences with the GC content of at least 50% have also been associated with human recombination hotspots (56,57).

Our findings indicate that small rare recurrent deletions of 2q21.1 between LCR2q21.1 and LCR2q21.1q21.2 are pathogenic for DD/ID, ADHD, epilepsy and other neurobehavioral abnormalities. This segment harbors five annotated genes with ARHGEF4 and GPR148 as possible candidate genes. We propose that additional studies in patients with these neurodevelopmental phenotypes should include analysis of the ARHGEF4 and GPR148 genes for copy-number changes and/or sequence mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject recruitment

Individuals with deletions and duplications involving 2q21.1 were identified after referral for clinical chromosomal microarray testing to the Medical Genetics Laboratories (MGL) at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM).

Patients

Patient 1 is a 12.5-year-old boy with ADHD, social anxiety and language impairment evidenced by spelling and pronunciation difficulties. He had memory deficits and atypical behaviors such as head banging. He was able to perform fourth-grade class work during his home schooling. Despite a normal gestational and birth history and size, his weight and height accelerated at about 3.5 years. Gynecomastia was noted at 4 years. He developed diabetes type 2 at 10 years, and acanthosis nigricans, obesity, tall stature and continued gynecomastia at the time of genetic evaluation. His bone age was 15.5–16 years. He was also found to have an occipital cystic hygroma. Methylation testing to rule out Prader–Willi syndrome was normal. There is a positive paternal family history for diabetes type 2 and polycystic kidney disease. His father is deceased from liver cancer. Normal parental intelligence is reported. His mother is not available for genetic testing.

Patient 2 is a 5.5-year-old female referred for evaluation of possible Williams–Beuren syndrome. She was born to a 29-year-old G4P1Ab2 mother at 42 weeks of gestation. Her birth weight was 7 pounds 4 ounces, and she was 21 inches in length. The pregnancy was complicated by maternal diabetes. She smiled at 3 months, rolled at 4 months, sat at 6 months, crawled at 5–6 months, stood at 7 months and walked at 10 months. Her mother reports a history of easy distraction, hyperactivity and resistance to instructions. Family history is significant for ADHD, including father and two paternal half siblings. Upon physical exam, she was noted to have mild dysmorphic features, including hypertelorism, wide spaced teeth and clinodactyly. Her parents are unavailable for genetic testing.

Patient 3 is a 6.5-year-old boy with mild DD, ADHD, behavioral problems, seizures, abnormal EEG and dysmorphic features. During the neuropsychological evaluation at age 5 years 9 months, he was found to have a Full Scale IQ of 83 with 16.1 percentile (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-III, WPPSI-III). His language was impaired with elements of dyslexia, dyscalculia and dysnomia. His speech was rapid and not understandable. He could not function in a regular classroom and required supervision. He displayed poor memory, poor organizational skills and distractibility. His behavior was aggressive, self-focused, defiant and anxious. There is a positive family history of bipolar disease (paternal grandmother and paternal great aunt), schizophrenia (paternal uncle), depression and epilepsy (paternal aunts). Maternal family history is positive for drug addiction and alcoholism. His 11-year-old brother has been diagnosed with ADHD and his mother has a diagnosis of depression. She was reported to be unable to make decisions, has low self-esteem and is anxious, fearful and paranoid. Upon physical exam, he was at the 10th percentile for height, 25th percentile for weight and 25th percentile for occipital-frontal circumference (OFC). He was noted to have slanted palpebral fissures, prominent lips, high palate, cupped ears with flat anthelix, upturned nose with bulbous tip, broad thumbs, clinodactyly of fifth fingers, joint hyper mobility, flat feet, hockey stick palmer creases and hirsutism. He was prescribed lamotrigine for seizures.

Patient 4 is a 17-year-old adopted male with ADHD, encephalopathy, borderline cognitive ability and conduct disorder. His biological parents had cognitive delays and disabilities. He was prescribed methylphenidate HCL extended release for ADHD.

Patient 5 is a 3-year-old boy with profound DD, intractable epilepsy and microcephaly. There was a gestational history of poor fetal movement. He was delivered by C-section with normal birth weight (7 pounds 6 ounces) and normal Apgars. The newborn history was characterized by temperature instability, feeding difficulties (G-tube placement) and jaundice. At 3 weeks, he had acute encephalopathy and began to have recurrent seizures that were initially tonic and tonic-clonic. He subsequently developed refractory flexor infantile spasms having up to 500 per day. He has failed medication trials with phenobarbital, levetiracetam, topiramate, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin and prednisolone. He is currently on the ketogenic diet and is prescribed zonisamide. His evaluation included normal test results for Fragile X, ARX (including sequence analysis), plasma amino acids and urinary organic acids. Cerebral spinal fluid studies included normal results for glucose, protein, amino acids, lactate, pyruvate and neurotransmitters. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed bilateral symmetric posterior occipital cystic encephalomalacia with cortical laminar necrosis and cerebral atrophy consistent with hypoxic ischemia. An MRI SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) revealed a global decrease in NAA (N-acetyl-aspartate, left more than right) without lactate peak as well as an increased myoinositol, most likely secondary to gliosis. Upon physical exam, he is at the 50th percentile for height, 50th percentile for weight and OFC was at 40.4 cm at 19 months (−6 SD). He is non-verbal and does not follow objects when they are presented. He shows axial hypotonia with mild distal spasticity. Reflexes show hypertonia. He has severe global DD with cortical blindness, cannot roll-over or sit and is taking nothing by mouth, all nutrition is received through a gastrostomy tube.

Duplication patients

We have also identified five unrelated families with reciprocal duplications (patients 6-10, ages 6.5, 7.0, 9.5, 9.5, and 1.0 years, respectively). Although detailed clinical information was not obtained, the indication provided for testing for most patients included ASDs (patients 6, 7 and 9), DD/ID (patients 7, 8 and 9), ADHD (patient 7), organic encephalopathy (patient 7), seizures (patient 9) and cardiac defect (patient 10). Patient 8 was adopted, but the biological father was reported to be unaffected. Patient 9 has significant family history with six of nine siblings affected with autism, Asperger syndrome or epilepsy. The father of patient 9 also has epilepsy. Parental samples for the other three patients were unavailable for testing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of genetic and clinical findings in patients 1–10

| Pt | Age (years) | Sex | CNV coordinates (hg18) | Gain/loss | Parental Inheritance | 2q21.1 CNVs in other family members | Other reported CNVs | Clinical phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.5 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Loss | Parental DNA unavailable | Unknown | None | ADHD, social anxiety, language impairment, memory deficits, atypical behaviors, gynecomastia, diabetes type 2, Acanthosis nigricans, occipital cystic hygroma, obesity and tall stature |

| 2 | 5.5 | F | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Loss | Parental DNA unavailable | Unknown | None | Easy distraction, hyperactivity and resistance to instructions |

| 3 | 6.5 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Loss | Inherited from affected mother | Brother with ADHD | None | Mild DD, ADHD, language impairment, behavioral problems, seizures, abnormal EEG and dysmorphic features |

| 4 | 17 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Loss | Adopted | Unknown | None | ADHD, encephalopathy, borderline cognitive ability and conduct disorder |

| 5 | 3 | M | chr2:131,204,290–132,356,498 | Loss | Inherited from unaffected mother | Unknown | chr17:2,942,086-3,331,777 (gain) | Profound DD, intractable recurrent epilepsy and microcephaly |

| 6 | 6.5 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Gain | Parental DNA unavailable | Unknown | None | ASDs |

| 7 | 9.5 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Gain | Inherited from unaffected father | Unknown | None | DD, ADHD, ASDs, organic encephalopathy |

| 8 | 7.0 | F | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Gain | Adopted | Unknown | None | DD/ID |

| 9 | 9.5 | F | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Gain | Inherited from affected father | Sister with Asperger syndrome | None | DD/ID, ASDs, seizures |

| 10 | 1 | M | chr2:131,204,290–131,621,552 | Gain | Parental DNA unavailable | Unknown | None | Cardiac defect |

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood via the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra System, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

aCGH analysis

A total of 17 035 unrelated subjects referred for CMA at the MGL at BCM were screened using custom-designed exon-targeted aCGH oligonucleotide microarrays (V8.0 and V8.1 OLIGO, 180 K) designed by the MGL at BCM (http://www.bcm.edu/geneticlabs/) and manufactured by Agilent Technology (Santa Clara, CA, USA) as previously described (58).

FISH analysis

Confirmatory and parental FISH analyses were performed using standard procedures.

MLPA analysis

Probes for MLPA analysis were designed using the freely available H-MAPD Web server (http://genomics01.arcan.stony-brook.edu/mlpa/cgi-bin/mlpa.cgi) and mapped in exons for the following genes: GPR148, FAM123C, ARHGEF4, FAM168B and PLEKHB2. MLPA reactions were carried out using SALSA MLPA reagents and P300 reference probe mix as per instructions (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam). MLPA product (1.1 µl) and 0.25 µl of GS500 Liz Size Standard were added to 10 µl of formamide and loaded onto an ABI 3730xl capillary electrophoresis machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using Genemarker MLPA analysis software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA).

Bioinformatics and in silico sequence analysis

Genomic sequences based on oligonucleotide coordinates from the aCGH experiments were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser (NCBI build 36, March 2006, http://www.genome.ucsc.edu) and assembled using BLAT (UCSC browser), BLAST2 (NCBI, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the Sequencher v4.8 software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Interspersed repeat sequences were identified using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org). DNA GC content was analyzed with cpgplot (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/cpgplot).

To better visualize the chromosome architecture in the 2q21.1 region, we have used the ICAass (v 2.5) algorithm. The graphical display was performed using Miropeats (v 2.01) (The Genome Institute at Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA). The program was run using two thresholds of 1000 bp.

Long-range PCR and DNA sequencing

Given the recurrent breakpoint mapping to flanking LCRs, we hypothesized NAHR as a most likely molecular mechanism of formation of the 2q21.1 deletions. Thus, we designed long-range PCR primers to harbor at least three nucleotide mismatches based on paralogous sequence variants (also known as cis-morphisms) (59,60), forward primer specific to the directly oriented ∼109 kb subunit in the proximal 2q21.1 LCR cluster and reverse primer in the paralogous copy in the distal 2q21.1q21.2 LCR cluster. This allowed preferential amplification of the predicted junction fragment, generated in the recombinant LCR as a product of NAHR. Primers were designed using the Primer 3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). Amplification of 10–20 kb fragments was performed using Takara LA Taq Polymerase (TaKaRa Bio USA, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Amplification of the GC-rich region in the LCRs was performed in the presence of 4% dimethyl sulfoxide, with the following conditions: 94°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 68°C for 7–12 min) and 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA) to remove unconsumed dNTPs and primers, and directly sequenced by Sanger di-deoxynucleotide sequencing using the initial primers and primers specific for both proximal and distal copies of the LCRs (Lone Star Labs, Houston, TX, USA).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Joanna Wiszniewska for helpful discussion.

Conflict of Interest statement. J.R.L. is a consultant for Athena Diagnostics, owns stock in 23andMe and Ion Torrent Systems Inc. and is a co-inventor on multiple US and European patents for DNA diagnostics. Furthermore, the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine derives revenue from molecular diagnostic testing (MGL, http://www.bcm.edu/geneticlabs/).

FUNDING

This study was supported in part by the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC, grant P30 HD024064) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (National Institutes of Health, grant R01 NS058529) to J.R.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lupski J.R. Genomic disorders ten years on. Genome Med. 2009;1:42. doi: 10.1186/gm42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupski J.R. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998;14:417–422. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunetti-Pierri N., Berg J.S., Scaglia F., Belmont J., Bacino C.A., Sahoo T., Lalani S.R., Graham B., Lee B., Shinawi M., et al. Recurrent reciprocal 1q21.1 deletions and duplications associated with microcephaly or macrocephaly and developmental and behavioral abnormalities. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1466–1471. doi: 10.1038/ng.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mefford H.C., Sharp A.J., Baker C., Itsara A., Jiang Z., Buysse K., Huang S., Maloney V.K., Crolla J.A., Baralle D., et al. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:1685–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stankiewicz P., Kulkarni S., Dharmadhikari A.V., Sampath S., Bhatt S.S., Shaikh T., Xia Z., Pursley A.N., Cooper M.L., Shinawi M., et al. Recurrent deletions and reciprocal duplications of 10q11.21q11.23 including CHAT and SLC18A3 are likely mediated by complex low-copy repeats. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:165–179. doi: 10.1002/humu.21614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Kovel C.G.F., Trucks H., Helbig I., Mefford H.C., Baker C., Leu C., Kluck C., Muhle H., von Spiczak S., Ostertag P., et al. Recurrent microdeletions at 15q11.2 and 16p13.11 predispose to idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Brain. 2010;133:23–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp A.J., Mefford H.C., Li K., Baker C., Skinner C., Stevenson R.E., Schroer R.J., Novara F., De Gregori M., Ciccone R., et al. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:322–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinawi M., Schaaf C.P., Bhatt S.S., Xia Z., Patel A., Cheung S.W., Lanpher B., Nagl S., Herding H.S., Nevinny-Stickel C., et al. A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1269–1271. doi: 10.1038/ng.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss L.A., Shen Y., Korn J.M., Arking D.E., Miller D.T., Fossdal R., Saemundsen E., Stefansson H., Ferreira M.A., Green T., et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and Autism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinawi M., Liu P., Kang S.-H.L., Shen J., Belmont J.W., Scott D.A., Probst F.J., Craigen W.J., Graham B.H., Pursley A., et al. Recurrent reciprocal 16p11.2 rearrangements associated with global developmental delay, behavioural problems, dysmorphism, epilepsy, and abnormal head size. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:332–341. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girirajan S., Rosenfeld J.A., Cooper G.M., Antonacci F., Siswara P., Itsara A., Vives L., Walsh T., McCarthy S.E., Baker C., et al. A recurrent 16p12.1 microdeletion supports a two-hit model for severe developmental delay. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:203–209. doi: 10.1038/ng.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannes F.D., Sharp A.J., Mefford H.C., de Ravel T., Ruivenkamp C.A., Breuning M.H., Fryns J.P., Devriendt K., Van Buggenhout G., Vogels A., et al. Recurrent reciprocal deletions and duplications of 16p13.11: the deletion is a risk factor for MR/MCA while the duplication may be a rare benign variant. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46:223–232. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elia J., Gai X., Xie H.M., Perin J.C., Geiger E., Glessner J.T., D'arcy M., deBerardinis R., Frackelton E., Kim C., et al. Rare structural variants found in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder are preferentially associated with neurodevelopmental genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams N.M., Zaharieva I., Martin A., Langley K., Mantripragada K., Fossdal R., Stefansson H., Stefansson K., Magnusson P., Gudmundsson O.O., et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1401–1408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesch K.P., Selch S., Renner T.J., Jacob C., Nguyen T.T., Hahn T., Romanos M., Walitza S., Shoichet S., Dempfle A., et al. Genome-wide copy number variation analysis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: association with neuropeptide Y gene dosage in an extended pedigree. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:491–503. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lionel A.C., Crosbie J., Barbosa N., Goodale T., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Rickaby J., Gazzellone M., Carson A.R., Howe J.L., Wang Z., et al. Rare copy number variation discovery and cross-disorder comparisons identify risk genes for ADHD. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:95ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinawi M., Sahoo T., Maranda B., Skinner S.A., Skinner C., Chinault C., Zascavage R., Peters S.U., Patel A., Stevenson R.E., et al. 11p14.1 microdeletions associated with ADHD, autism, developmental delay, and obesity. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A:1272–1280. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elia J., Glessner J.T., Wang K., Takahashi N., Shtir C.J., Hadley D., Sleiman P.M., Zhang H., Kim C.E., Robison R., et al. Genome-wide copy number variation study associates metabotropic glutamate receptor gene networks with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2011;44:78–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasky-Su J., Neale B.M., Franke B., Anney R.J.L., Zhou K., Maller J.B., Vasquez A.A., Chen W., Asherson P., Buitelaar J., et al. Genome-wide association scan of quantitative traits for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identifies novel associations and confirms candidate gene associations. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008;147B:1345–1354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesch K.P., Timmesfeld N., Renner T.J., Halperin R., Roser C., Nguyen T.T., Craig D.W., Romanos J., Heine M., Meyer J., et al. Molecular genetics of adult ADHD: converging evidence from genome-wide association and extended pedigree linkage studies. J. Neural Transm. 2008;115:1573–1585. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neale B.M., Lasky-Su J., Anney R., Franke B., Zhou K., Maller J.B., Vasquez A.A., Asherson P., Chen W., Banaschewski T., et al. Genome-wide association scan of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008;147B:1337–1344. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasky-Su J., Won S., Mick E., Anney R.J.L., Franke B., Neale B., Biederman J., Smalley S.L., Loo S.K., Todorov A., et al. On genome-wide association studies for family-based designs: an integrative analysis approach combining ascertained family samples with unselected controls. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neale B.M., Medland S., Ripke S., Anney R.J.L., Asherson P., Buitelaar J., Franke B., Gill M., Kent L., Holmans P., et al. Case-control genome-wide association study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:906–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neale B.M., Medland S.E., Ripke S., Asherson P., Franke B., Lesch K.-P., Faraone S.V., Nguyen T.T., Schäfer H., Holmans P., et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:884–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mick E., Todorov A., Smalley S., Hu X., Loo S., Todd R.D., Biederman J., Byrne D., Dechairo B., Guiney A., et al. Family-based genome-wide association scan of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faraone S.V., Perlis R.H., Doylem A.E., Smoller J.W., Goralnick J.J., Holmgren M.A., Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gizer I.R., Ficks C., Waldman I.D. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum. Genet. 2009;126:51–90. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faraone S.V., Doyle A.E., Mick E., Biederman J. Meta-analysis of the association between the 7-repeat allele of the dopamine D-4 receptor gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:1052–1057. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe N., Kirley A., Hawi Z., Sham P., Wickham H., Kratochvil C.J., Smith S.D., Lee S.Y., Levy F., Kent L., et al. Joint analysis of the DRD5 marker concludes association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder confined to the predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:348–356. doi: 10.1086/381561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purper-Ouakil D., Wohl M., Mouren M.C., Verpillat P., Ades J., Gorwood P. Meta-analysis of family-based association studies between the dopamine transporter gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2005;15:53–59. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li D.W., Sham P.C., Owen M.J., He L. Meta-analysis shows significant association between dopamine system genes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2276–2284. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang B., Chan R.C.K., Jing J., Li T., Sham P., Chen R.Y.L. A meta-analysis of association studies between the 10-repeat allele of a VNTR polymorphism in the 3’-UTR of dopamine transporter gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144B:541–550. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Silva M.G., Elliott K., Dahl H., Fitzpatrick E., Wilcox S., Delatycki M., Williamson R., Efron D., Lynch M., Forrest S. Disruption of a novel member of a sodium/hydrogen exchanger family and DOCK3 is associated with an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-like phenotype. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:733–740. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.10.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brookes K., Xu X., Chen W., Zhou K., Neale B., Lowe N., Anney R., Franke B., Gill M., Ebstein R., et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markunas C.A., Quinn K.S., Collins A.L., Garrett M.E., Lachiewicz A.M., Sommer J.L., Morrissey-Kane E., Kollins S.H., Anastopoulos A.D., Ashley-Koch A.E. Genetic variants in SLC9A9 are associated with measures of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in families. Psychiatr. Genet. 2010;20:73–81. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283351209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang-James Y., DasBanerjee T., Sagvolden T., Middleton F.A., Faraone S.V. SLC9A9 mutations, gene expression, and protein–protein interactions in rat models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2011;156:835–843. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poelmans G.P.G., Pauls D.L., Buitelaar J.K., Franke B. Integrated genome-wide association study findings: identification of a neurodevelopmental network for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:365–377. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10070948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaul R., Gao G.P., Aloya M., Balamurugan K., Petrosky A., Michals K., Matalon R. Canavan disease: mutations among Jewish and non-Jewish patients. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994;55:34–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaag A., Anikster Y., Christensen E., Glustein J.Z., Fois A., Michelakakis H., Nigro F., Pronicka E., Ribes A., Zabot M.T., et al. The molecular basis of canavan (aspartoacylase deficiency) disease in European non-Jewish patients. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;57:572–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myers S., Freeman C., Auton A., Donnelly P., McVean G. A common sequence motif associated with recombination hot spots and genome instability in humans. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1124–1129. doi: 10.1038/ng.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirov G., Grozeva D., Norton N., Ivanov D., Mantripragada K.K., Holmans P. Craddock N., Owen M.J., O'Donovan M.C. International Schizophrenia Consortium, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Support for the involvement of large copy number variants in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:1497–1503. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itsara A., Cooper G.M., Baker C., Girirajan S., Li J., Absher D., Krauss R.M., Myers R.M., Ridker P.M., Chasman D.I., et al. Population analysis of large copy number variants and hotspots of human genetic disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zogopoulos G., Ha K.C., Naqib F., Moore S., Kim H., Montpetit A., Robidoux F., Laflamme P., Cotterchio M., Greenwood C., et al. Germ-line DNA copy number variation frequencies in a large North American population. Hum. Genet. 2007;122:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conrad D.F., Pinto D., Redon R., Feuk L., Gokcumen O., Zhang Y., Aerts J., Andrews T.D., Barnes C., Campbell P., et al. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature. 2010;464:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature08516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaikh T.H., Gai X., Perin J.C., Glessner J.T., Xie H., Murphy K., O'Hara R., Casalunovo T., Conlin L.K., D'Arcy M., et al. High-resolution mapping and analysis of copy number variations in the human genome: a data resource for clinical and research applications. Genome Res. 2009;19:1682–1690. doi: 10.1101/gr.083501.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rommelse N.N.J., Arias-Vasquez A., Altink M.E., Buschgens C.J.M., Fliers E., Asherson P., Faraone S.V., Buitelaar J.K., Sergeant J.A., Oosterlaan J., et al. Neuropsychological endophenotype approach to genome-wide linkage analysis identifies susceptibility loci for ADHD on 2q21.1 and 13q12.11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawasaki Y., Senda T., Ishidate T., Koyama R., Morishita T., Iwayama Y., Higuchi O., Akiyama T. Asef, a link between the tumor suppressor APC and G-protein signaling. Science. 2000;289:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiesen S., Kubart S., Ropers H.H., Nothwang H.G. Isolation of two novel human RhoGEFs, ARHGEF3 and ARHGEF4, in 3p13–21 and 2q22. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;273:364–369. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gloriam D.E.I., Schioth H.B., Fredriksson R. Nine new human Rhodopsin family G-protein coupled receptors: identification, sequence characterisation and evolutionary relationship. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1722:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto M., Straub R.E., Marenco S., Nicodemus K.K., Matsumoto S.-I., Fujikawa A., Miyoshi S., Shobo M., Takahashi S., Yarimizu J., et al. The evolutionarily conserved G protein-coupled receptor SREB2/GPR85 influences brain size, behavior, and vulnerability to schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6133–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derwińska K., Bernaciak J., Wiśniowiecka-Kowalnik B., Obersztyn E., Bocian E., Stankiewicz P. Autistic features with speech delay in a girl with an ∼1.5-Mb deletion in 6q16.1, including GPR63 and FUT9. Clin. Genet. 2009;75:199–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Comai G., Boutet A., Neirijnck Y., Schedl A. Expression patterns of the Wtx/Amer gene family during mouse embryonic development. Dev. Dyn. 2010;239:1867–1878. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krappa R., Nguyen A., Burrola P., Deretic D., Lemke G. Evectins: vesicular proteins that carry a pleckstrin homology domain and localize to post-Golgi membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu H.E., Hawash K., Picker J., Stoler J., Urion D., Wu B.L., Shen Y. A recurrent 1.71 Mb genomic imbalance at 2q13 increases the risk of developmental delay and dysmorphism. Clin. Genet. 2012;81:257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan Y., Linardopoulou E., Friedman C., Williams E., Trask B.J. Genomic structure and evolution of the ancestral chromosome fusion site in 2q13–2q14.1 and paralogous regions on other human chromosomes. Genome Res. 2002;12:1651–1662. doi: 10.1101/gr.337602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagshaw A.T.M., Pitt J.P.W., Gemmell N.J. Association of poly-purine/poly-pyrimidine sequences with meiotic recombination hot spots. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramocki M.B., Bartnik M., Szafranski P., Kołodziejska K.E., Xia Z., Bravo J., Miller G.S., Rodriguez D.L., Williams C.A., Bader P.I., et al. Recurrent distal 7q11.23 deletion including HIP1 and YWHAG identified in patients with intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, and neurobehavioral problems. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szafranski P., Schaaf C.P., Person R.E., Gibson I.B., Xia Z., Mahadevan S., Wiszniewska J., Bacino C.A., Lalani S., Potocki L., et al. Structures and molecular mechanisms for common 15q13.3 microduplications involving CHRNA7: benign or pathological? Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:840–850. doi: 10.1002/humu.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lupski J.R. Genomic disorders: recombination-based disease resulting from genomic architecture. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:246–252. doi: 10.1086/346217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindsay S.J., Khajavi M., Lupski J.R., Hurles M.E. A chromosomal rearrangement hotspot can be identified from population genetic variation and is coincident with a hotspot for allelic recombination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:890–902. doi: 10.1086/508709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]