Abstract

Background

This study investigated the relationship between drug use and sex work patterns and sex work income earned among street-based female sex workers (FSWs) in Vancouver, Canada.

Methods

We used data from a sample of 129 FSWs who used drugs in a prospectivec cohort (2007–2008), for a total of 210 observations. Bivariate and multivariable linear regression using generalized estimating equations was used to model the relationship between explanatory factors and sex work income. Sex work income was log-transformed to account for skewed data.

Results

The median age of the sample at first visit was 37 years (interquartile range[IQR]: 30–43), with 46.5% identifying as Caucasian, 48.1% as Aboriginal and 5.4% as another visible minority. The median weekly sex work income and amount spent on drugs was $300 (IQR = $100–$560) and $400 (IQR = $150–$780), respectively. In multivariable analysis, for a 10% increase in money spent on drugs, sex work income increased by 1.9% (coeff: 0.20, 95% CIs: 0.04–0.36). FSWs who injected heroin, FSWs with higher numbers of clients and youth compared to older women (<25 versus 25+ years) also had significantly higher sex work income.

Conclusions

This study highlights the important role that drug use plays in contributing to increased dependency on sex work for income among street-based FSWs in an urban Canadian setting, including a positive dose-response relationship between money spent on drugs and sex work income. These findings indicate a crucial need to scale up access and availability of evidence-based harm reduction and treatment approaches, including policy reforms, improved social support and economic choice for vulnerable women.

Keywords: sex workers, drug use, income, addiction treatment, harm reduction, evidence-based policies

1. INTRODUCTION

Like many other occupations, sex work is conducted primarily for economic gain. There are obvious differences that separate sex work from other occupations, including the increased risks to sexual health and safety, social and economic vulnerability and a high degree of marginalization and criminalization in many settings (Blanchard et al., 2005, Dandona et al., 2006, Rekart, 2005, Shannon et al., 2008a and Strathdee et al., 2008). The social stigmatization (Della Guista et al., 2005 and Scambler and Paoli, 2008) and lack of legal regulation (Hubbard et al., 2008 and Letheby et al., 2008) are arguably among the main characteristics of sex work that separate it from other professions in which bodily services (e.g., massage) are provided.

The vulnerability of women in sex work to sex work-related harms including high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV, violence and poverty, and marginalization and isolation from health and social services has been well-documented (Rekart, 2005).

A high concentration of harms has consistently been found in settings where street-based sex work and drug markets coexist (Cusick, 2006, Harcourt et al., 2001, Harcourt and Donovan, 2005, Lowman, 2000, Pyett and Warr, 1997, Rekart, 2005 and Shannon et al., 2008a). Drug use has been found to be an important antecedent to entry into street-based sex work for women (Malta et al., 2008 and Weber et al., 2004), including early initiation into sex work (Loza et al., 2010) and engaging in sex work for survival (Chettiar et al., 2010 and DeBeck et al., 2007). Qualitative and ethnographic studies have documented that many women depend on income from sex work to sustain drug use or to gain access to other commodities such as food and shelter (Aral and St. Lawrence, 2002, Shannon et al., 2007, Shannon et al., 2008a and Strathdee et al., 2008). A dependence on sex work for income in the context of drug use can have a substantial impact on sex workers’ health, safety and well-being. female sex workers (FSWs) who use drugs may earn less money than their non-drug-using counterparts, with increased pressures in negotiating prices due to immediacy of drug withdrawal and need to sustain drug habit (Aral and St. Lawrence, 2002). Concurrently, FSWs who use drugs or with increased dependence on drugs may also be more susceptible to agreeing to clients’ desires for sexual practices which can earn more money but carry higher risk for HIV/STIs (e.g., having anal sex or not using condoms) (Aral and St. Lawrence, 2002). In many North American settings, the introduction of inexpensive and widely available crack cocaine has been documented by women to result in being paid less per sexual transaction, heightening their economic vulnerability (e.g., “$5 dates”) (Maher, 2000 and Shannon et al., 2008a). Further, direct and indirect drug-sharing practices between sex workers and clients have been shown to increase the likelihood of clients offering and workers accepting more money for unprotected sex (Shannon et al., 2008a).

Income earned from sex work reflects the numbers of sexual transactions that women have with clients and the amount that women charge per client. A number of interpersonal and individual factors may influence the amount charged, including the type of sex act performed, the numbers of sex acts per client, the relationship with the client, condom use and characteristics of the sex worker (e.g., age, duration in sex work, work environment) (Gertler et al., 2005, Johnston et al., 2010, Rao et al., 2003 and Shannon et al., 2008a). As such, sex work income represents a complex set of factors measuring risk, vulnerability and economic dependence on sex work, particularly for those women who use drugs. Of the few studies that explore sex work earnings, most have focused on the economic costs to women when they practice safer sex behaviour (e.g., the amount women could lose by refusing to not use condoms), or have presented theoretical economic models describing how compensation for sex work is linked with health and social costs (e.g., stigma, forgone marriage opportunities, social exclusion, risks to health, safety and well-being) (Cameron and Collins, 2003, Della Giusta, 2010, Della Guista et al., 2005 and Edlund and Korn, 2002).

Despite the importance of drug use in influencing women’s initiation into and dependence on sex work for income relative to those women who do not use drugs, comparatively fewer studies have examined how the street cost of drugs, types of drug use and sex work characteristics independently relate to income earned by FSWs. The independent relationship between the street cost of drugs and amount earned through sex work is of particular interest in this study, as assessing this relationship can quantify the acute vulnerability and susceptibility that sex workers who use drugs face within the context of the drug market, and help contextualize the impact of structural-environmental factors affecting fluctuations in this market, including changes in drug prices, that are outside of their control. For example, police crackdowns that remove large quantities of drugs from drug markets can result in a local increase in the street cost of drugs (Beyrer et al., 2010, Strathdee et al., 2010 and Wood et al., 2010). This analysis can also provide important insights into practices of engaging in higher-risk behaviour in individual transactions in order for women to earn enough sex work income to still be able to afford drug use. Moreover, identifying drug use and sex work patterns associated with higher sex work income can point to groups of individuals who have a higher economic dependence on sex work to support their drug habit and who might benefit in particular from evidence-based harm reduction and treatment approaches. Therefore, we aimed to characterize the amount of money spent on drugs and earned through sex work by street-based FSWs who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada and examine the drug use and sex work patterns associated with higher income earned from sex work.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and sample

This analysis is based on data from a prospective cohort of street-based sex workers as part of a community-based HIV prevention research partnership. A detailed description of the methodology is published elsewhere (Shannon et al., 2007). Briefly, between April, 2006 and May, 2008, 255 women who were engaged in street-based sex work (inclusive of transgendered women) were recruited and consented to participate in a prospective cohort study (response rate of 93%), including baseline and bi-annual questionnaires and voluntary HIV screening, through systematic time-spacing sampling, social mapping and targeted outreach to sex work strolls (Stueve et al., 2001). These street-based solicitation spaces were identified through a participatory mapping exercise conducted by current/former sex workers. Eligibility criteria included being female or transgender aged 14 years or older who smoked or injected illicit drugs (not including marijuana) in the past month and who was actively engaged in street-level sex work in Vancouver. The study was approved through the Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board and the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

2.2. Survey instrument

At baseline and follow-up visits (conducted every six months), a detailed questionnaire administered face-to-face by peer researchers (i.e., current/former FSWs who were trained and experienced in conducting community-based research) elicited responses related to demographics, health and addiction service use, working conditions, violence and safety, and sexual and drug-related harms. Data from this questionnaire has been used in many other recent studies (Deering et al., 2010, Shannon et al., 2008b, Shannon et al., 2009a and Shannon et al., 2009b).

2.3. Measures

The primary outcome was average weekly sex work income earned, derived from the survey item, “Over the last 6 months, what were your main sources of income and how much did you generate from each of these sources weekly?”

We assessed multiple measures describing drug use and sex work patterns and their relationships with sex work income. These included the average weekly money spent on drugs (derived from the item: “How much money do you think you spend on drugs in one week?”), which represents the street cost of drugs, and type of drug use (cocaine or heroin injection, and crystal methamphetamine injection/non-injection) during the past six months. Given the high rate of crack cocaine smoking in this population (Shannon et al., 2009a and Shannon et al., 2009b), we also considered daily intensive crack smoking (≥10 versus <10 times per day on average in the past six months). We also assessed the effects of interpersonal drug-related and sexual risk factors (e.g., receptive sharing of used syringes and/or pipes; having an intimate, non-commercial sexual partner; exchanging sex while high on crack cocaine; numbers of clients per week; condom use by clients in vaginal/anal sex; and being pressured by clients to not use condoms).

Social factors considered included age (<25 years versus 25+ years) ethnicity (‘Caucasian’ versus ‘ethnic minority’, including individuals of Aboriginal, First Nations, Metis, or Inuit ancestry, Hispanic, Asian or Black). Based on previous research in Vancouver and elsewhere (Rhodes, 2002 and Shannon et al., 2009a), we derived two categories of structural/contextual variables: (1) Living environment and (2) Work environment. Living environment was constructed as either homeless in the last six months (sleeping on the street for one night or more in the last six months versus not) or not homeless. Work environment factors included place of solicitation in the last six months (e.g., type of working area or sex work stroll), including main street/commercial areas or alleys, side streets or industrial settings, and place of servicing clients being primarily in indoor locations (e.g., hourly rooms, saunas) or primarily outdoor locations (e.g., alleys, cars).

We also adjusted for the amount of income earned through other sources, which included government-administered income (welfare, disability and nutrition supplements), legal informal sources (binning, panhandling, partner’s income and under-the-table jobs), legal formal sources (temporary job, regular job) as well as non-legal sources (drug-related, e.g., dealing). All monetary amounts were reported in Canadian dollars.

2.4. Statistical analysis

As information on sex work income was only collected in follow-up questionnaires, this analysis was restricted to all participants who completed at least one follow-up visit (November 2007–October 2008). Social variables (age and ethnicity) reported at baseline were considered as fixed variables. All other factors were treated as time-updated covariates (answered at each follow-up visit) that referred to experiences occurring during the previous six-month period. As done previously (DeBeck et al., 2009, Richardson et al., 2008 and Shannon et al., 2009b), to account for correlation between repeated measures for each subject (since women may have answered one or two surveys during this period, depending on when they were enrolled), we used generalised estimating equations (GEEs) for the analysis of correlated data; thus, data from each participant’s follow-up visit was included. GEE methods provided standard errors adjusted by repeated observations per person using an exchangeable correlation structure. Missing data were addressed through the GEE estimating mechanism, which uses the all available pairs method to encompass the missing data from dropouts or intermittent missing data. All non-missing pairs of data are used in the estimators of the working correlation parameters. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (2002–2003), (UCLA: Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group, n.d.).

Bivariate and multivariable linear regression with GEEs was used to model the relationship between drug use and sex work patterns and weekly sex work income earned. For use in linear regression, sex work income, money spent on drugs, numbers of clients and other income earned were log-transformed to address highly skewed data. In order to adjust for potential confounding, all variables that were significant on a p < 0.10 level in GEE bivariate analyses were entered in a multivariable linear GEE model. Variables were retained as significant in the multivariable model with an alpha cut-off of p < 0.05. Bivariate and multivariable GEE regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed and all p-values are two-sided. We reported percent increases in the regression coefficients.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

Of the 255 participants enrolled in the prospective cohort, 167 women completed at least one follow-up visit (mean = 2, range: 1–2 visits) in the 12-month period, and were therefore potentially eligible for our analyses. Overall, 129 reported valid information on sex work income at their first survey visit, providing a total of 210 (78.7%) observations for this study. The median age of the 129 women at their first survey visit in this sample was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 30–43 years). Of this sample, 46.5% (60) of women identified as Caucasian, 48.1% (62) as Aboriginal and 5.4% (7) as another visible minority. Table 1 provides additional details for the sample at their first survey visit related to social and environmental factors, drug use and sex work patterns. We compared women with and without valid responses to sex work income and found no significant differences between the two samples in terms of age (pooled t-test: p = 0.71), ethnicity (Chi-squared test: p = 0.07) and money spent on drugs (pooled t-test: p = 0.64).

Table 1.

Select factors describing the sample of female sex workers in Vancouver, Canada, with valid responses to the outcome ‘average sex work income earned per week’ at their first survey administered. Median sex work income (interquartile range) is also provided, across social and environmental factors and sex work and drug use patterns.

| Factors | Percent (N) N = 129 |

Median sex work income |

|---|---|---|

| Median amount earned from sex work per weekb | $300 ($100–$560) | |

| Median amount spent on drugs per weekb | $400 ($150–$780) | |

| Median amount earned per week through other incomea,b |

$700 ($525–$1000) | |

| Median numbers of clients per weekb | 5.5 (2–13) | |

| Age | ||

| <25 years | 39.5 (51) | $500 ($200–$800) |

| 25+ years | 60.5 (78) | $200 ($100–$500) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 46.5 (60) | $435 ($145–$600) |

| Ethnic minority | 53.5 (69) | $200 ($100–$500) |

| Currently homeless | ||

| Yes | 40.3 (52) | $200 ($100–$650) |

| No | 59.7 (77) | $300 ($140–$500) |

| Inject heroinb | ||

| Yes | 44.2 (57) | $500 ($200–$800) |

| No | 55.8 (72) | $200 ($100–$500) |

| Inject cocaineb | ||

| Yes | 32.6 (42) | $300 ($100–$600) |

| No | 67.4 (87) | $250 ($100–$500) |

| Inject/smoke crystal methb | ||

| Yes | 18.6 (24) | $290 ($100–$800) |

| No | 81.4 (105) | $300 ($150–$500) |

| Daily intensive crack smokingb | ||

| Yes | 35.7 (46) | $500 ($200–$600) |

| No | 64.3 (83) | $200 ($100–$560) |

| Receptive sharing of used pipe and/or syringeb | ||

| Yes | 51.9 (67) | $225 ($150–$700) |

| No | 48.1 (62) | $300 ($100–$500) |

| Had an intimate partnerb | ||

| Yes | 45.8 (54) | $300 ($150–$500) |

| No | 54.2 (64) | $300 ($100–$750) |

| Pressured into unprotected sex by clientb | ||

| Yes | 29.4 (32) | $300 ($175–$580) |

| No | 70.6 (77) | $300 ($200–$600) |

| Condoms always used by clientb | ||

| Yes | 17.1 (21) | $350 ($200–$800) |

| No | 82.9 (102) | $275 ($100–$560) |

| Exchange sex while on crackb | ||

| Yes | 59.1 (65) | $300 ($150–$500) |

| No | 40.9 (45) | $200 ($100–$500) |

| Solicit in main/commercial areasb | ||

| Yes | 32.6 (42) | $500 ($200–$800) |

| No | 67.4 (87) | $200 ($100–$500) |

| Solicit in alleys/industrial areasb | ||

| Yes | 31.0 (40) | $300 ($100–$500) |

| No | 69.0 (89) | $300 ($150–$600) |

| Service clients mainly in indoor public placesb | ||

| Yes | 51.2 (66) | $212 ($100–$560) |

| No | 48.8 (63) | $350 ($150–$600) |

| Service clients mainly in outdoor public placesb | ||

| Yes | 33.3 (43) | $420 ($200–$600) |

| No | 67.7 (86) | $200 ($100–$560) |

Includes government-administered income (welfare, disability, nutritional supplement), legal informal sources (binning, panhandling, partner’s income, under-the-table job), legal formal sources (temporary job, regular job) as well as non-legal sources (drug-related, i.e. dealing).

Last six months.

3.2. Sex work income

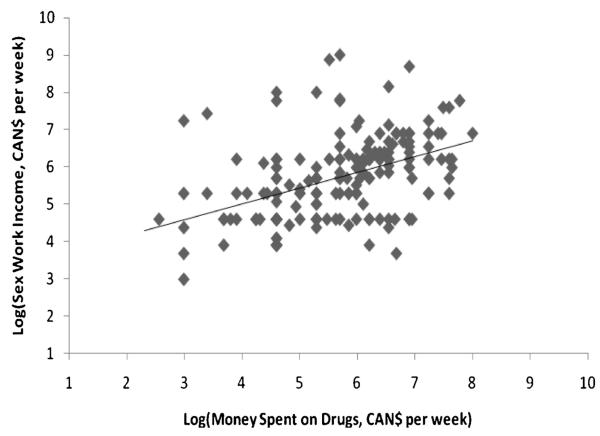

In a typical week, at their first survey visit, women reported earning a median of $300 (mean: $500, IQR: $100–$560) from sex work income, spent a median of $400 (mean: $572, IQR: $150–$780) on drugs and had a median of 5.5 (mean: 11, IQR: 2–13) clients. Overall, 95% of women reported having some other income, earning a weekly median of $700 (mean: $780, IQR: $525–$1000) from this income. At their first survey visit, women who earned higher weekly sex work income were more likely to be younger (<25 versus 25+ years), Caucasian, not currently homeless, inject heroin, inject cocaine, report intensive daily crack smoking, not engage in receptive sharing of used pipes or syringes, always use condoms with clients, exchanged sex while high on crack, solicit clients in main/commercial areas and not service clients in indoor establishments (Table 1). Fig. 1 describes the relationship between the log-transformed weekly amount spent on drugs and the log-transformed weekly sex work income earned. A best-fitting linear regression line depicts the linear, positive relationship between the two variables.

Figure. 1.

The linear relationship between the log-transformed money spent on drugs and log-transformed weekly sex work income earned among female sex workers in Vancouver, Canada.

In bivariate linear regression with GEE for the total sample, age, heroin injection, cocaine injective, intensive daily crack smoking, exchanging sex while high on crack, greater number of clients and the amount spent on drugs were significantly associated with higher sex work income.

Table 2 displays results from multivariable linear regression with GEEs. In multivariable analysis, for a 10% increase in the amount of money spent on drugs, sex work income earned increased by 1.9% (coeff: 0.20, 95% CIs: 0.04–0.36). We also found that there was a significant association between numbers of clients and sex work income earned, with a 10% increase in the numbers of clients associated with a 3.0% increase in sex work income (coeff: 0.32, 95% CIs: 0.19–0.42). In addition, women who were <25 years old compared to those who were 25+ years reported significantly higher sex work income earned, with younger women having a 43% increase in sex work income (coeff: 0.36, 95% CIs: 0.08–0.64) relative to older women. Women who injected heroin had a significant increase in sex work income of 51% (coeff: 0.41, 95% CIs: 0.11–0.70) relative to women who did not.

Table 2.

Multivariable GEE coefficients for linear regression of the relationship between social, drug use and environmental factors and sex work income (log), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for coefficients.

| Factor | Coefficient (95% CIs) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Amount spent on drugs per week (log) | 0.20 (0.04–0.36) | 0.017 |

| Amount earned from other income per weeka | NS | – |

| Numbers of clients per week (log) | 0.32 (0.19–0.42) | <0.001 |

| Age <25 years | 0.36 (0.08–0.64) | 0.012 |

| Caucasian | NS | – |

| Currently homeless | NS | – |

| Inject heroinb | 0.41 (0.11–0.70) | 0.007 |

| Inject cocaineb | NS | – |

| Inject/smoke crystal methb | NS | – |

| Daily intensive crack smokingb | 0.02 (−0.31 to 0.35) | 0.888 |

| Receptive sharing of used pipe and/or syringeb | NS | – |

| Had an intimate partnerb | NS | – |

| Pressured into unprotected sex by clientb | NS | – |

| Condoms always used by client | 0.31 (−0.01 to 0.65) | 0.065 |

| Exchange sex while on crackb,c | ||

| Solicit in main/commercial areasb | NS | – |

| Solicit in alleys/industrial areasb | NS | – |

| Service clients indoorsb | NS | – |

| Service clients outdoorsb | NS | – |

Includes government-administered income (welfare, disability, nutritional supplement), legal informal sources (binning, panhandling, partner’s income, under-the-table job), legal formal sources (temporary job, regular job) as well as non-legal sources (drug-related, i.e. dealing).

Last six months.

Sample size of valid responses too small to include in multivariable analysis.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the relationship between the street cost of drugs, drug use and sex work patterns by street-based female sex workers in an urban Canadian setting. We found that in a typical week, women reported earning a median of $300 from sex work income, spent a median of $400 on drugs and had a median of 6 clients. Overall, 95% of women reported having some other income (including that from financial assistance, other legal employment and illegal activities), earning a weekly median of $700 (mean = $780) from this income. The amount of money spent on drugs, heroin injection, numbers of clients and being younger (<25 versus 25+) were independently significantly associated with higher sex work income in multivariate analysis.

Our study is the first that we are aware of to empirically demonstrate an independent, positive dose-response relationship between the amount of money spent on drugs by women in a street-based sex market and the amount of money they earn through sex work. This was the case even after adjusting for the type of drugs used and numbers of clients, indicating that another mechanism could be influencing the amount of income earned. Women who spend more on drugs may engage in sexual behaviour for which they can earn more money per transaction, including vaginal or anal sex as compared to oral sex. Many studies have suggested that, due to constrained economic conditions, FSWs can be influenced by clients’ demands to have sex without condoms in exchange for higher pay, including in our setting (Cusick, 1998, Johnston et al., 2010, Luke, 2006 and Shannon et al., 2008a). Of note, in contrast to this research, consistent condom use by clients was associated with higher sex work income suggesting other dynamics may interact to shape the relationship between condom use by clients and weekly sex work income in street-based sex work economies, such as work environment and client population factors. The additional economic pressure of increased drug use (as represented by increased money spent on drugs, and thus the street cost of drugs) may also influence sex worker’s vulnerability to engage in riskier behaviours (Strathdee et al., 2008). Although we adjusted for consistent condom use by clients, this cannot capture the complexity of higher-risk transactions. Women who spend more money on drugs could also be having more than one sex act per client in order to earn a higher sex work income (e.g., regular compared to one-time clients). This could potentially increase their vulnerability to HIV/STIs, given that women use condoms less frequently with regular compared to occasional clients (Hanck et al., 2008, Malta et al., 2008, Reza-Paul et al., 2008 and Shannon et al., 2008a).

The cost to FSWs associated with street heroin injection was also significantly and independently related to increased sex work income. In part, this is likely due to the increased cost for heroin relative to other drugs. Women in sex work who use heroin may be more economically vulnerable and dependent on sex work for income than women who use other types of drugs, since the average per-point (per-unit) cost of heroin has been shown in our setting to be approximately double the cost of cocaine (Wood et al., 2003). Heroin users have also been shown to need to use more street heroin due to its low purity compared with prescription heroin. However, since this association remained significant even after adjusting for the amount of money spent on drugs, women’s dependency on heroin combined with its higher cost may influence women to engage in higher-risk behaviour for which they can earn more money, as described above. In contrast to the relationship with street heroin, street-based FSWs who were intensive crack users or cocaine users were not more likely to earn a higher sex work income. This supports previous research indicating that the shift in Vancouver to widely available stimulant crack cocaine, a less expensive street drug than injection heroin, may downwardly influence the amount that women can charge and clients will pay for services (Shannon et al., 2008a). These results also suggest that the relationship between crack cocaine use and sex work income in a street-based sex market may not be adequately captured in a linear model, likely due to several factors, including crack’s low street price, and direct sex-for-crack exchanges (Maher, 2000).

Collectively, our findings support global calls, including from the World Health Organization, for an evidence-based public health approach to drug use and sex work, and to scale up the availability of treatment, prevention and support (Lutnick and Cohan, 2009, Shannon, 2010 and Wood et al., 2010). Our results in particular underscore the social costs of heroin dependency and indicate that alternative approaches, such as opiate-substitution therapy as an essential medicine, should be considered. Recent clinical trials in this setting suggest that opiate-substitution therapies (including prescription heroin substitution, methadone maintenance therapy, and injectable diacetylmorphine) can be highly effective and have been associated with a substantial reduction in average amount of money spent on drugs (Oviedo-Joekes et al., 2009 and Schwartz et al., 2006), indicating that this could be a potentially important intervention to reduce harm to vulnerable women who engage in sex work to sustain heroin use. Alternative regulatory practices with respect to drug use that adhere to evidence-based drug policies would facilitate the scale-up and implementation of these new approaches (Wood et al., 2010). Given the clear association between the street cost of drugs and sex work income in our study, and the relationship between regulatory practices toward drug use that remove large quantities of drugs from drug markets and subsequently drive down drug purity while driving up costs (Beyrer et al., 2010, Strathdee et al., 2010 and Wood et al., 2010), such alternative regulatory practices could help reduce sex work-related harms relating to the increased need to earn higher sex work income to support drug use. Improving access and utilization of addictions treatment for women in sex work could also reduce women’s dependence on sex work earnings to support drug use. This approach should be coupled with other low-threshold training, employment and/or improved economic security (Young and Mulvale, 2009), including evaluation of programs to support transitioning out of sex work for survival. Increased economic control for sex workers may be a critical HIV intervention strategy in promoting condom negotiation with clients, or reducing the likelihood that women will engage in other riskier behaviour in exchange for higher earnings per sex act. A shift away from current criminalized approaches to prostitution could additionally disentangle the underground sex work and drug markets by moving sex work to safer indoor work spaces and promoting increased economic control and choice for FSWs (such as FSWs ability to regulate fee structures, opportunities for those who wish to exit sex work) (Shannon et al., 2008c). Evidence suggests removal of criminal sanctions would promote sex work occupational safety by reducing violence, increasing access to health and social support services and increasing women’s safety and ability to negotiate condom use with clients (Lutnick and Cohan, 2009, Makin, 2010 and Shannon, 2010).

When viewed in tandem with studies of income among non-drug using sex workers, our results also confirm that youth can generate a higher income from sex work compared with older sex workers (Gertler et al., 2005 and Moffatt and Peters, 2004). This age differential in sex work income may reflect increased bargaining power (and amount charged per transaction) due to higher demand for young sex workers among male clients, and is comparable to findings among other entertainment industries and levels of the sex work industry (Shannon et al., 2008a). While younger women in our study were also more likely to spend more on drugs, the association between younger age and higher sex work income was retained after adjusting for drug use patterns as well as the numbers of clients.

This study has several limitations. The study population included only women in street-level sex work; since sex work is conducted across many other types of venues (e.g., massage parlours, brothels), the results may not be generalizable to FSWs in other venues. Since sampling frames are difficult to construct for hidden populations including FSWs, the sample was not randomly generated and may not be representative of street-based FSWs in other settings. However, to address these challenges, time-space sampling was used to systematically sample women at staggered times and locations based on street-level solicitation spaces identified through mapping, therefore helping attract a representative sample (Stueve et al., 2001). Some questions may also be perceived to be sensitive, including sex work income, and thus self-reported behaviour may be subject to social desirability bias or higher non-response rates. To address this, women were interviewed in a place where they felt comfortable (including the local sex work service agency or the study site). Women were interviewed by their peers (current or former sex workers), helping to increase their comfort and accuracy of responses. The study measures also were developed through extensive input from the community of sex workers, service providers and other stakeholders. We also found no significant differences between samples of women who did and did not provide valid responses to the survey item on sex work income. We targeted a difficult-to-access, hidden and marginalized population with high health care and drug treatment needs; the use of regression with GEEs allowed us to adjust for multiple measurements made on the same participant at different follow-ups. Although it is not possible to confirm the direction of association, the relationship between sex work income and money spent on drugs is significant, even when we adjusted for other factors including the numbers of clients and the amount of money earned through other sources, and is supported by ethnographic research indicating the strong relationship between level of addiction and involvement in sex work (Maher, 2000, Shannon et al., 2007, Shannon et al., 2008a and Strathdee et al., 2008).

In summary, our study findings indicate a crucial need to scale up access and availability of evidence-based harm reduction and addiction treatment strategies, including heroin maintenance therapy and alternative regulatory frameworks for drug use. Our results suggest the need to rigorously pilot and evaluate evidence-based interventions that promote economic control and choice among street-based sex workers, alongside removal of criminal sanctions targeting sex work.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women for time and expertise and our peer research team (Shari, Laurie, Chanel, Rose, Shawn, Tammy, Adrian). We thank our community advisory board and sex work and community partner agencies, as well as Peter Vann, Ruth Zhang, Calvin Lai and Kate Gibson for their research and administrative support.

Role of funding source: This research was primarily funded through an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and National Institutes of Health Research (grant #1R01DA028648-01A1). KND is supported by the CIHR. JS is supported by an Applied Public Health Chair from the CIHR. MWT is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. KS is partially supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award and NIH (grant #1R01DA028648-01A1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, or in analysis and interpretation of the results, and this paper does not necessarily reflect views or opinions of the funders.

Footnotes

Contributors: KD and KS contributed to the conceptual design of the article and analyses plan. KD conducted all statistical analyses and prepared the initial draft. All other authors provided content expertise and critical feedback on the paper.

Conflict of interest: All of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- FAQ . How do I interpret a regression model when some variables are log transformed? Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group; UCLA: 2010. n.d. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/mult_pkg/faq/general/log_transformed_regression.htm, accessed on. [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, St. Lawrence JS. The Ecology of Sex Work and Drug Use in Saratov Oblast, Russia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:798–805. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Sidibe M, Strathdee SA. Time to act: a call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. The Lancet. 2010;376:551–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60928-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JF, O’Neil J, Ramesh BM, Bhattacharjee P, Orchard T, Moses S. Understanding the Social and Cultural Contexts of Female Sex Workers in Karnataka, India: Implications for Prevention of HIV Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191:S139–S146. doi: 10.1086/425273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron S, Collins A. Estimates of a model of male participation in the market for female heterosexual prostitution services. European Journal of Law and Economics. 2003;16:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Chettiar J, Shannon K, Wood E, Zhang R, Kerr T. Survival sex work involvement among street-involved youth who use drugs in a Canadian setting. J Public Health. 2010;32:322–327. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick L. Non-use of condoms by prostitute women. AIDS Care. 1998;10:133–146. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick L. Widening the harm reduction agenda: From drug use to sex work. International J Drug Policy. 2006;17:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dandona R, Dandona L, Gutierrez JP, Kumar AG, McPerson S, Samuels F, Bertozzi SM. Demography and sex work characteristics of female sex workers in India. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-6-5. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-698x-6-5.pdf, accessed on. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Shannon K, Wood E, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Income generating activities of people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Small W, Wood E, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Public injecting among a cohort of injecting drug users in Vancouver, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:81–86. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, Gibson K, Irons L, Shannon K. A peer-led mobile outreach program and increased utilization of detoxification and residential drug treatment among female sex workers who use drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;113:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Giusta M. Simulating the impact of regulation changes on the market for prostitution services. European Journal of Law and Economics. 2010;29:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Della Guista M, Di Tommaso ML, Strøm S. The market for prostitution services. University of Oslo Department of Economics; 2005. Who’s watching? p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund L, Korn E. A Theory of Prostitution. Journal of Political Economy. 2002;110:181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler P, Shah M, Bertozzi SM. Risky Business: The Market for Unprotected Commercial Sex. Journal of Political Economy. 2005;113:518–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hanck SE, Blankenship KM, Irwin KS, West BS, Kershaw T. Assessment of self-reported sexual behavior and condom use among female sex workers in India using a polling box approach: a preliminary report. Sex Transm. Dis. 2008;35:489–494. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181653433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt C, Beek I, Heslop J, McMahon M, Donovan B. The health and welfare needs of female and transgender street sex workers in New South Wales. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001;25:84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt C, Donovan B. The many faces of sex work. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:201–206. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard P, Matthews R, Scoular J. Regulating sex work in the EU: prostitute women and the new spaces of exclusion. Gender, Place and Culture. 2008;15:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CL, Callon C, Li K, Wood E, Kerr T. Offer of financial incentives for unprotected sex in the context of sex work. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letheby G, Williams K, Birch P, Cain M, editors. Sex as a crime? Willan Publishing; Uffculme, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lowman L. Violence and the Outlaw Status of (Street) Prostitution in Canada. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:987–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Loza O, Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Staines H, Ojeda VD, Martínez GA, Amaro H, Patterson TL. Correlates of Early versus Later Initiation into Sex Work in Two Mexico-U.S. Border Cities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke N. Exchange and Condom Use in Informal Sexual Relationships in Urban Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2006;54:319–348. [Google Scholar]

- Lutnick A, Cohan D. Criminalization, legalization or decriminalization of sex work: what female sex workers say in San Francisco, USA. Reprod. Health Matters. 2009;17:38–46. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L. Sexed work: gender, race and resistance in a Brooklyn dex market. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Makin K. Judge decriminalizes prostitution in Ontario, but Ottawa mulls appeal. The Globe and Mail CTVglobemedia Publishing Inc.; Ottawa, Canada: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malta M, Monteiro S, Lima RMJ, Bauken S, Marco A.d., Zuim GC, Bastos FI, Singer M, Strathdee SA. HIV/AIDS risk among female sex workers who use crack in Southern Brazil. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2008;42:830–837. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102008000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt PG, Peters SA. Scottish Journal of Political Economy. Blackwell Publishing Limited; 2004. Pricing Personal Services: An Empirical Study of Earnings in the UK Prostitution Industry; pp. 675–690. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, Lauzon P, Guh D, Anis A, Schechter MT. Diacetylmorphine versus Methadone for the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:777–786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyett PM, Warr DJ. Vulnerability on the streets: female sex workers and HIV risk. AIDS Care. 1997;9:539–547. doi: 10.1080/713613193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V, Gupta I, Lokshin M, Jana S. Sex workers and the cost of safe sex: the compensating differential for condom use among Calcutta prostitutes. Journal of Development Economics. 2003;71:585–603. [Google Scholar]

- Rekart ML. Sex-work harm reduction. The Lancet. 2005;366:2123–2134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67732-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza-Paul S, Beattie T, Syed HUR, Venukumar KT, Venugopal MS, Fathima MP, Raghavendra H, Akram P, Manjula R, Lakshmi M, Isac S, Ramesh BM, Washington R, Mahagaonkar SB, Glynn JR, Blanchard JF, Moses S. Declines in risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infection prevalence following a community-led HIV preventive intervention among female sex workers in Mysore India. AIDS. 2008;22:S91–S100. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343767.08197.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L, Wood E, Zhang R, Montaner J, Tyndall M, Kerr T. Employment Among Users of a Medically Supervised Safer Injection Facility. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:519–525. doi: 10.1080/00952990802146308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Software, 2002–2003. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: p. 9.1. [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G, Paoli F. Health work, female sex workers and HIV/AIDS: Global and local dimensions of stigma and deviance as barriers to effective interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1848–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Highfield DA, Jaffe JH, Brady JV, Butler CB, Rouse CO, Callaman JM, O’Grady KE, Battjes RJ. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Interim Methadone Maintenance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:102–109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K. The hypocrisy of Canada’s prostitution legislation. CMAJ. 2010;182:1388. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Bright V, Allinott S, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. [accessed on January 15, 2008];Community-based HIV prevention among substance-using women in survival sex work: the Maka Project Partnership. Harm Reduction Journal. 2007 4 doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-20. http://harmreductionjournal.com/content/4/1/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science and Medicine. 2008a;66:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Bright V, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Drug sharing with clients as a risk marker for increased violence and sexual and drug-related harms among survival sex workers. AIDS Care. 2008;20:235–241. doi: 10.1080/09540120701561270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, M.W. T. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: Implications for HIV prevention strategies and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2009a;99:659–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW. [accessed on August 11, 2009];Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009b 339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2939. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/339/aug11_3/b2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008b;19:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, Hankins CA. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. The Lancet. 2010;376:268–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Philbin MM, Semple SJ, Pu M, Orozovich P, Martinez G, Lozada R, Fraga M, de la Torre A, Staines H, Magis-Rodríguez C, Patterson TL. Correlates of injection drug use among female sex workers in two Mexico-U.S. border cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, O’Donnell LN, Duran R, San Doval A, Blome J. Time-Space Sampling in Minority Communities: Results With Young Latino Men Who Have Sex With Men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:922–926. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber AE, Boivin J-F, Blais L, Haley N, Roy É. [accessed on October 20, 2009];Predictors of initiation into prostitution among female street youths. Journal of Urban Health. 2004 81 doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth142. http://www.springerlink.com/content/c712075x4q873658/fulltext.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Anis AH, Hogg RS, Montaner JSG, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: investigation of a massive heroin seizure. CMAJ. 2003;168:165–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Werb D, Kazatchkine M, Kerr T, Hankins C, Gorna R, Nutt D, Des Jarlais D, Barré-Sinoussi F, Montaner J. Vienna Declaration: a call for evidence-based drug policies. The Lancet. 376:310–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M, Mulvale JP. Possibilities and prospects: the debate over guaranteed income. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; Ottawa, Canada: 2009. [Google Scholar]