Abstract

Otological intra cranial complications are still a major problem in developing countries. Otogenic brain abscess is a serious, life-threatening complication of otitis media and it usually occurs due to attico antral ear disease. Treatment of otogenic brain abscess is immediate surgical drainage, and mastoidectomy is done to remove the source of infection. This article describes three cases of otogenic brain abscess secondary to attico antral ear disease, which were less than 1.6 cm in size and were treated conservatively with antibiotic therapy. All the patients were started on intravenous antibiotic therapy and serial CT scan was done to monitor the progression of the brain abscess. Canal wall down mastoidectomy was done for the removal of otogenic source of infection. Antibiotic therapy was continued for 6 weeks. Post operative CT scan was done after 8 weeks and it showed complete resolution of the abscess. This study showed that small otogenic brain abscess, which are less than 1.6 cm in size responded to treatment with antibiotics, could be managed by medical therapy. Surgery was required only for the management of attico antral ear disease. To best of our knowledge this is the first review on conservative management of small otogenic brain abscess secondary to attico antral ear disease.

Keywords: Otogenic brain abscess, Attico antral ear disease, Conservative management

Introduction

The proximity of the middle ear cleft and mastoid air cells to the intratemporal and intracranial compartments places structures located in these areas at increased risk of infectious complications [1]. The occurrence of chronic suppurative otitis media and its complications have reduced considerably with the use of better antibiotics [2]. In the pre-antibiotic era, intracranial complications secondary to ear disease occurred in 2.3–6.4% of cases. After the introduction of antibiotics, sophisticated imaging techniques and more refined surgical techniques, intracranial complication rates have been reduced to 0.04–0.15% [3]. However, in the developing countries; these infections still occurs frequently and are major challenges with respect to diagnosis and management. They can be lethal if they are not identified and treated properly [1, 2, 4].

Brain abscess is the second most common intracranial complication of otitis media after meningitis, but it is perhaps the most lethal [1, 5]. Previous antibiotic therapy can change the classical clinical picture of otogenic intracranial complications and may cause delay in diagnosis [4]. If the diagnosis of otogenic brain abscess is made early in the course of the disease, early institution of antibiotics therapy helps in stopping further progression and thus avoids the necessity for the neurosurgical drainage. The otologist should recognize the early neurotological symptoms and signs of the complications of otitis media. Early diagnosis and timely surgical interventions are essential for good results.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 38-year-old male patient, who had intermittent right ear discharge for the past 18 years, came for treatment of fever, headache, and blurred vision. Patient had intermittent foul smelling ear discharge for the past 18 years and it used to subside with antibiotics therapy. For the past 1 month ear discharge was continuous and it was associated with intermittent fever and chills. He also had headache and vomiting, and vomiting stopped with treatment. His vision was blurred for the past 10 days and he was unable to identify people from distance. He was driver by profession and hence came for the treatment. Patient had received many antibiotics tablets before coming to the hospital.

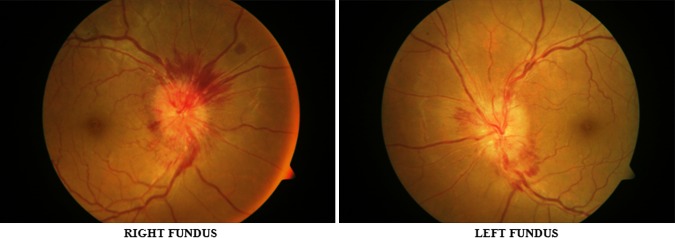

On examination patient was febrile and well oriented. Right pinna and postaural area were normal and mastoid area was non-tender. Scanty foul smelling ear discharge was present in the right ear canal. Otoscopic examination showed an attic perforation and rest of the tympanic membrane congested. Eustachian tube was not patent. Left ear, nose, and throat were normal. There were no meningeal signs and fundus examination showed bilateral papilledema. PTA showed mixed hearing loss. CT scan of temporal bone showed a soft tissue non-enhancing mass in the attic and antrum on the right side. CT scan of brain showed a non-enhancing hypodense lesion in the right temporal lobe suggestive of cerebritis (Fig. 1). Ear pus culture did not show any growth. Pure tone audiogram showed mixed hearing loss.

Fig. 1.

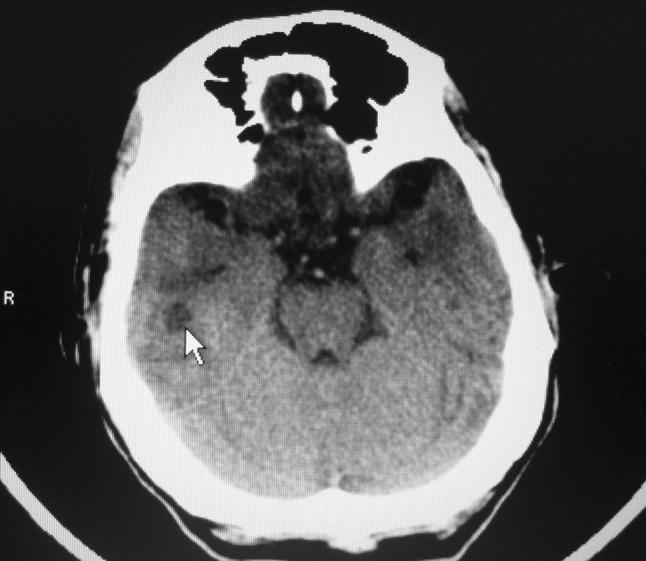

CT scan of brain showing (arrow) non-enhancing hypodense lesion in the right temporal lobe

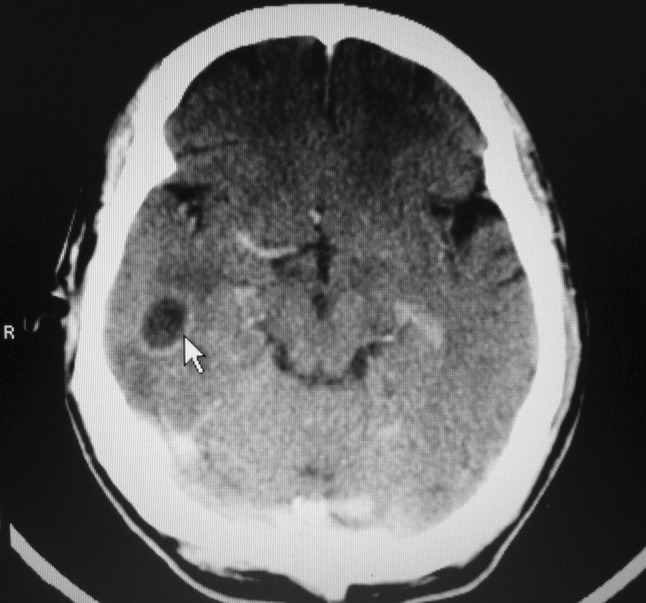

Patient was started on ceftriaxone, amikacin, and mannitol and there was clinical improvement in patient condition. Repeat CT scan of brain on seventh day showed rounded hypodense lesion in the right temporal lobe. CT scan with contrast showed right temporal lobe ring enhancing lesion (Fig. 2) measuring 1.42 × 1.5 cm with minimal perilesional edema and dilated ventricles (Fig. 3). Fundoscopic examination showed bilateral papilledema (Fig. 4). As the size of the abscess was small to be operated, and patient condition started improving with antibiotics therapy, decision was taken in consultation with neurosurgeons to manage temporal lobe lesion with antibiotics therapy. Patient had otitis media with cholesteatoma, mastoid exploration was planned to remove the focus of infection from the ear.

Fig. 2.

CT scan with contrast showing (arrow) ring enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe

Fig. 3.

CT scan of brain showing dilated ventricles

Fig. 4.

Pre-operative fundus photograph showing papilledema

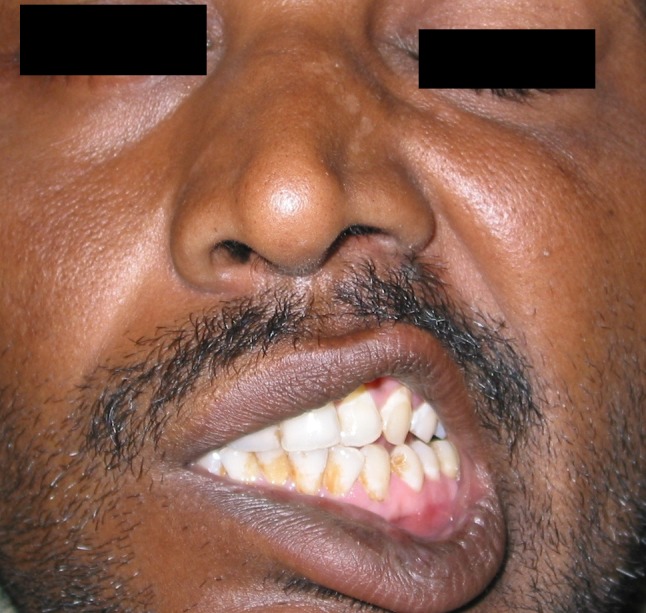

Right mastoid exploration was done under general anesthesia. Cholesteatoma was present in the attic, mesotympanum and it was extending into the antrum. Cholesteatoma had partially eroded the mastoid portion of the fallopian canal. Along with cholesteatoma, granulation tissue was also present in the mastoid antrum. Incus and stapes superstructure was eroded by cholesteatoma. Cholesteatoma and granulation tissue were removed and canal wall down mastoidectomy was done. Patient had facial palsy after mastoidectomy (Fig. 5) and it recovered completely after 20 days (Fig. 6). After 1 month following surgery, patent vision started improving and fundoscopic examination showed reduction in papilledema (Fig. 7). Patient was given intravenous antibiotics for 6 weeks and at the end of 2 months CT scan showed resolved abscess.

Fig. 5.

Patient photograph showing right facial palsy

Fig. 6.

Patient photograph showing recovery from facial palsy

Fig. 7.

Post-operative fundus photograph showing reduction in papilledema

Case II

A 50-year-old male patient who had right ear discharge for the past 10 years was referred for the treatment of fever, headache, and vertigo. Patient had intermittent ear discharge and decreased hearing for the past 10 years and discharge used to subside with treatment. Present episode of ear discharge and fever started 20 days back. It foul smelled and did not reduce with treatment. Patient developed head ache 10 days back and it was associated with giddiness.

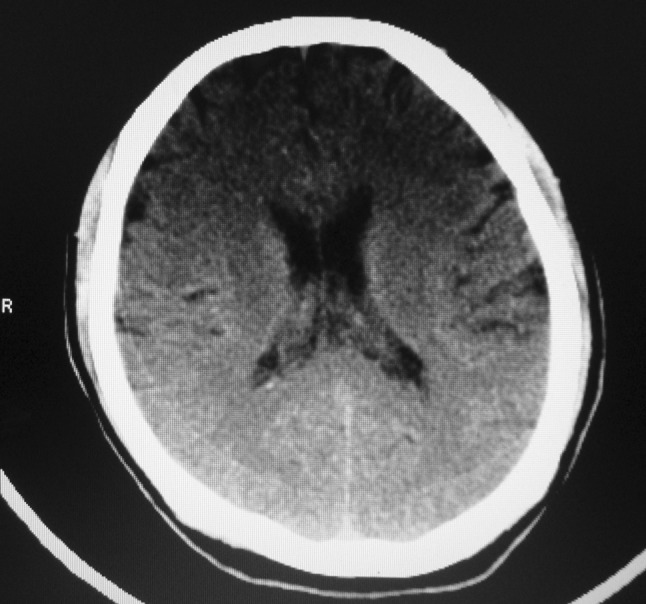

Otolaryngological examination showed a posterio-superior marginal subtotal perforation and cholesteatoma in the pars tensa with mucopurulent foul smelling scanty discharge. Fistula test was negative. Left ear, nose, and throat were normal. CT scan of temporal bone showed soft tissue mass in right middle ear and mastoid. CT scan showed a hypodense non-enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe suggestive of cerebritis. Patient was started on ceftriaxone and amikacin and metronidazole and there was clinical improvement in patient condition. Repeat CT scan of brain with contrast on tenth day, showed right temporal lobe ring enhancing lesion measuring 1.5 × 1.3 cm (Fig. 8). Ear swab culture showed proteus vulgaris organism. PTA showed mixed hearing loss.

Fig. 8.

Plain CT scan and CT with contrast showing ring enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe

As the size of the abscess was less than 1.6 cm, and patient condition started improving with antibiotics therapy, decision was taken in consultation with neurosurgeons to manage temporal lobe lesion with antibiotics therapy. Patient had otitis media with secondary acquired type of cholesteatoma, canal wall down mastoidectomy was planned to remove the focus of infection from the ear.

Right mastoid exploration was done under general anesthesia. Cholesteatoma was present in the middle ear and it was extending into the antrum. Along with cholesteatoma, granulation tissue was also present in the middle ear and mastoid antrum. Malleus incus and stapes superstructure was eroded by cholesteatoma. Cholesteatoma and granulation tissue was removed and canal wall down mastoidectomy was done. Post operative period was uneventful. Patient was given intravenous antibiotics for 6 weeks and at the end of 2 months CT scan showed resolved abscess.

Case III

An 18-year-old male patient from a rural area presented with fever profuse right ear discharge and headache. Patient had continuous small quantity ear discharge for the past 5 years. Since 15 days ear discharge has become profuse, foul smelling, and it is associated with low fever. He did not get any relief with the medical treatment at a rural hospital and developed headache. Patient was referred to major hospital for further management.

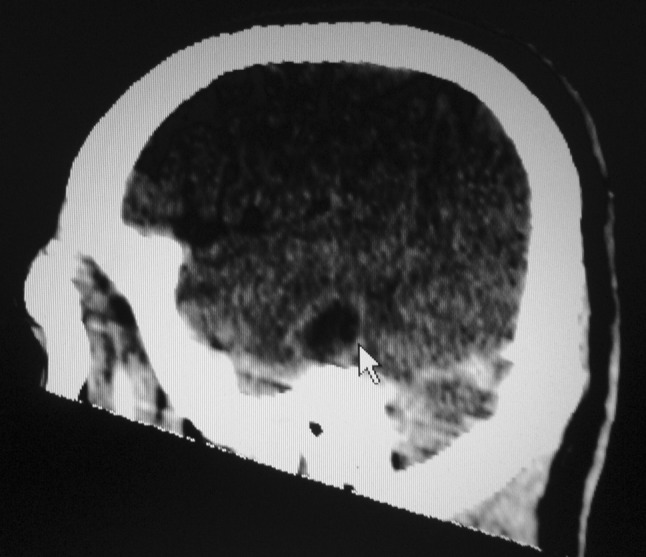

On examination patient was febrile and well oriented. Right pinna and post aural area was normal and mastoid tenderness was absent. Thick foul smelling discharge was present in the ear canal. Otoscopic examination showed attic retraction pocket with cholesteatoma. PTA showed mixed hearing loss. CT scan showed a hypodense lesion in the right temporal lobe suggestive of cerebritis. Patient was started on intravenous antibiotics. Repeat CT scan after 7 days showed a ring enhancing lesion measuring 1.4 × 1.5 cm in the temporal lobe and it was attached to the petorus bone (Fig. 9). Ear swab culture showed proteus organism. As the size of the abscess was 1.6 cm, and patient showed improvement with antibiotics therapy, decision was taken in consultation with neurosurgeons to manage temporal lobe lesion with antibiotics therapy. Patient had otitis media with primary acquired type cholesteatoma, canal wall down mastoidectomy was planned to remove the focus of infection from the ear.

Fig. 9.

CT scan of brain showing (arrow) ring enhancing lesion in the temporal lobe and its attachment to the petrous bone

Right mastoid exploration was done under general anesthesia. Retraction pocket filled with cholesteatoma was present in the middle ear and it was extending into the antrum. Along with cholesteatoma, granulation tissue was also present in the mastoid antrum. Malleus and incus was eroded by cholesteatoma. Cholesteatoma and granulation tissue was removed and canal wall down mastoidectomy was done. Post operative period was uneventful. Patient was given intravenous antibiotics for 6 weeks and at the end of 2 months CT scan showed resolved abscess.

Discussion

Brain abscess is a dreaded complication of otitis media and it almost exclusively result from COM [1, 5]. It commonly affects temporal lobe and cerebellum. Rarely does it occur in the occipital lobe [6]. Brain abscess may result from direct peri-vascular extension of infection and lie adjacent to the focus of infection or from retrograde thrombophlebitis and lie remote to the primary site [7].

Brain abscesses are located on the same side as the diseased ear. The temporal lobe and cerebellum are the two locations for otogenic brain abscess [5]. The temporal lobe abscess usually occurs in the middle and basal portions of the temporal lobe, adherent to the dura over the roof of the petrous bone [7]. Rarely abscess occurs in the occipital region and there is a report of occipital brain abscess occurring in the contralateral side [6]. The development of abscess in one hemisphere following infection in the contralateral mastoid can presumably occur from hematogenous spread of organisms [8, 9].

In the present study brain abscess was present on the same side as the diseased ear and they were attached to dura over the roof of the petrous bone.

The clinical progression occurs in three stages [1].

Encephalitic stage: In this initial stage symptoms are fever, rigors, nausea, vomiting, headache, and mental status changes or seizures.

Latent stage: in this stage acute symptoms abate, but general fatigue and listlessness persist.

Expansion of the abscess cavity stage: In this stage patients present with severe headaches, vomiting, fever, mental status changes, hemodynamic changes, and increased intracranial pressure.

Schwaber et al. [10] in their review on early signs and symptoms of neurotologic complication of chronic otitis media found that foul smelling ear discharge, fever, and headache were the significant early signs and symptoms of neurotologic complication of chronic otitis media.

In the present study all the three patients presented with foul smelling ear discharge, fever, and headache and only the first patient had features suggestive of raised intracranial pressure.

Pathogenesis of brain abscess occurs in four stages [11].

Stage of early cerebritis: This stage occurs between 1 and 3 days. In this stage there is formation of central necrotic foci, edema surrounded by perivascular inflammatory response.

Stage of late cerebritis: This stage occurs between 4 and 9 days. In this stage necrotic zone becomes more discrete and is surrounded by a peripheral zone of fibroblasts and neovascularization.

Early capsule stage: This stage occurs between 10 and 14 days. In this stage a distinct capsule begins to appear, with a well-developed layer of fibroblasts and an associated persistent cerebritis.

Late capsule stage: This stage occurs after 14 days. This stage corresponds to the completion and thickening of the capsule.

Abscess encapsulation is influenced by following factors [11]:

The organism involved;

The origin of infection (direct extension versus metastasis);

The immune status of the host;

Corticosteroid administration; and

Antibiotic therapy

Early therapy with newer antibiotics can stop further progression of the disease. In the present study all three patient s started showing clinical improvement with the commencement of intravenous antibiotics and serial CT scan did not show any increase in abscess size.

Diagnosis

In the presence of symptoms suggestive of intracranial complication, a contrast CT scan or MRI should be done while IV antimicrobial therapy is initiated [1].

Neuroimaging studies have been the most useful diagnostic tools in detecting and localizing early abscesses and in following their progress [5, 11]. MRI give better details about the abscess than CT scan. But CT scan is preferred because it gives valuable information about bony erosion of the mastoid, and can help in determining the cause of the abscess and the most appropriate treatment options [1]. On brain CT scan, brain abscesses are frequently found in the gray–white matter junction of the watershed regions between vascular territories. These abscesses have hypodense centers surrounded by smooth, regular thin-walled capsules with areas of ring enhancement [11]. CT scans help to rule out any associated intracranial complications, or evidence of increased intracranial pressure [1, 12]. The anatomic location, size of abscesses, stage of abscess formation, and neurologic status of the patient can influence the strategy for managing brain abscess [11, 13–16].

Surgical Management

The treatment of choice for brain abscess is neurosurgical drainage. Patient must be stabilized before neurosurgical intervention. Neurosurgical drainage is performed, either through an open craniotomy with drainage or excision, or by stereotactic aspiration through a burr hole [1]. After draining otogenic brain abscess, mastoidectomy should be done to remove the source of infection [5, 11] The appropriate time to perform the mastoidectomy is controversial. Murthy et al. [7] stated that first neurosurgical drainage and later ear operation should be done. According to Singh and Maharaj [17] and Mathews and Maurus [18], first neurosurgical drainage should be done, and later in the same setting mastoidectomy should be done [5].

According to Kurien et al. [19], craniotomy with concurrent mastoidectomy is not only safe, but also removes the source of infection at the same time the complication is being treated, thus avoiding reinfection while the patient is awaiting the ear surgery. In addition, the treatment is completed in single, shorter stay, which is economical for the patient.

In a study by Hafidh et al. [3], two patients underwent mastoid surgery before drainage of their brain abscess. Initial CT scans performed before ear explorations demonstrated brain edema, cerebritis. Follow-up CT scans after ear exploration showed that the cerebritis had progressed to a fully formed abscess. Neurosurgical drainage was done 12 days after the mastoid surgery. Eradicating the focus of infection in the ear did not prevent abscess progression. This may be due to large size of the abscess and infections not responding to antibiotic therapy.

In the present study all three patients started showing clinical improvement with the commencement of intravenous antibiotics. As the abscess size was less than 1.6 cms and serial CT scan did not show any increase in abscess size, neurosurgical drainage was not done.

Medical Management

Cheng et al. [11] reviewed strategies for the management of bacterial brain abscess. In their review they concluded that, non-surgical, empirical treatment is possible in certain patients, especially when the etiological agent is known with a reasonably high certainty as a result of positive cultures from CSF, or drainage from the ear or sinuses [11, 15, 16, 20, 21]. Serial CT or MRI scans are crucial during medical treatment because, abscesses may enlarge despite antibiotic treatment [22]. If neurologic deterioration occurs as a consequence of mass effect of an enlarging abscess, surgical removal of the abscesses is necessary.

Morwani and Jayashankar [23] are of the opinion that there is a role for conservative management of brain abscess which are smaller than 1 cm in diameter, with intravenous antibiotics and follow-up CT scans, together with eradication of otogenic septic focus at the earliest stage. They also stated that same concept holds well in the treatment of tiny residual abscess.

Postoperative clinical, hematological, and radiological monitoring is mandatory. Periodic neurological follow-up is imperative as intracranial pathology may manifest up to 3 weeks after the mastoid infection has been controlled [7].

After surgical intervention, IV antibiotics should be continued for several weeks and serial CT scans with contrast should be to assure resolution of the abscess [1, 24].

In the present study all three patients started showing clinical improvement with the commencement of intravenous antibiotics and serial CT scan did not show any increase in abscess size. Neurosurgical intervention was not required. All the three patients underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy. They responded well to medical management. Antibiotic therapy was continued for 6 weeks and post treatment CT scan showed abscess resolution.

Conclusion

This study showed that small otogenic brain abscess, which are less than 1.6 cm in size responded to treatment with antibiotics, could be managed by medical therapy. Surgery was required only for the management of attico antral ear disease. Close collaboration between otologist, neuroradiologists, and neurosurgeons, as well as adequate surgical interventions and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, remain the cornerstones of effective medical management of small brain abscess secondary to attico antral ear disease.

References

- 1.Smith JA, Danner CJ. Complications of chronic otitis media and cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006;39:1237–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey SP, Larawin V. Complications of otitis media and their management. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:264–267. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249728.48588.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hafidh MA, Keogh I, Walsh MC, et al. Otogenic intracranial complications. A 7-year retrospective review. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg. 2006;27:390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viswanatha B. Lateral sinus thrombosis with cranial nerve palsies. Int J Pediatr Otolaryngol Extra. 2007;2:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pedex.2007.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sennaroglu L, Sozeri B. Otogenic brain abscess: review of 41 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(6):751–755. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.107887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viswanatha B, Sarojamma, Vijayashree MS, Sumatha D. Unilateral attico antral ear disease with bilateral intracranial complications. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;64(1):82–86. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murthy PSN, Sukumar R, Hazarika P, Diwaker Rao A, Mukulchand, Raja A. Otogenic brain abscess in childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinol. 1991;22:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(91)90092-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernardini GL. Diagnosis and management of brain abscess and subdural empyema. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4:448–456. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathisen GE, Johnson JP. Brain abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:763–779. doi: 10.1086/515541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwabar MK, Pensak ML, Bartels LJ. The early signs and symptoms of neurotologic complications of chronic suppurative otitis media. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:373–375. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198904000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu CH, Chang WN, Lui CC. Strategies for the management of bacterial brain abscess. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanatha B. Otitic hydrocephalus: A report of 2 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89(7):E34. doi: 10.1177/014556131008900708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viswanartha B. Bilateral concurrent mastoidectomy: a rare indication in the treatment of otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2010;5:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pedex.2009.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelan MA, Hilal SK. Computed tomography as a guide in the diagnosis and follow-up of brain abscesses. Radiology. 1980;135:663–671. doi: 10.1148/radiology.135.3.7384453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liston TE, Tomasovic JJ, Stevens EA. Early diagnosis and management of cerebritis in a child. Pediatrics. 1980;65:484–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma BS, Gupta SK, Khosla VK. Current concepts in the management of pyogenic brain abscess. Neurol India. 2000;48:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh B, Maharaj TJ. Radical mastoidectomy: its place in otitic intracranial complications. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1113–1118. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100125435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathews TJ, Marus G. Otogenic intradural complications. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:121–124. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100104281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurien M, Job A, Mathew J, Mathew C. Otogenic intracranial abscess: concurrent craniotomy and mastoidectomy changing trend in a developing country. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(12):1353–1356. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.12.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidzinski J, Koszewski W. The value of different methods of treatment of brain abscess in the CT era. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1990;105:117–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01669993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenblum ML, Hoff JT, Norman D, et al. Nonoperative treatment of brain abscesses in selected high-risk patients. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:217–225. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.52.2.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black P, Graybill JR, Charache P. Penetration of brain abscess by systemically administered antibiotics. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:705–709. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.6.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morwani KP, Jayashankar N. Single stage transmastoid approach for otogenic intracranial abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:1216–1220. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109990533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harker LA, Shelton C. Complications of temporal bone infections. In: Cummings CW, editor. Cummings otolaryngology head and neck surgery. 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 3013–3038. [Google Scholar]