Abstract

Introduction

Approximately 15% of HIV-infected individuals have comorbid diabetes. Studies suggest that HIV and diabetes have an additive effect on chronic kidney (CKD) progression; however, this observation may be confounded by differences in traditional CKD risk factors.

Methods

We studied a national cohort of HIV-infected and matched HIV-uninfected individuals who received care through the Veterans Healthcare Administration. Subjects were divided into four groups based on baseline HIV and diabetes status, and the rate of progression to an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 45ml/min/1.73m2 was compared using Cox-proportional hazards modeling to adjust for CKD risk factors.

Results

31,072 veterans with baseline eGFR ≥ 45ml/min/1.73m2 (10,626 with HIV only, 5,088 with diabetes only, and 1,796 with both) were followed for a median of 5 years. Mean baseline eGFR was 94ml/min/1.73m2, and 7% progressed to an eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2. Compared to those without HIV or diabetes, the relative rate of progression was increased in individuals with diabetes only [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 2.48; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.19–2.80], HIV only [HR 2.80, 95% CI 2.50–3.15], and both HIV and diabetes [HR 4.47, 95% CI 3.87–5.17].

Discussion

Compared to patients with only HIV or diabetes, patients with both diagnoses are at significantly increased risk of progressive CKD even after adjusting for traditional CKD risk factors. Future studies should evaluate the relative contribution of complex comorbidities and accompanying polypharmacy to the risk of CKD in HIV-infected individuals, and prospectively investigate the use of cART, glycemic control, and adjunctive therapy to delay CKD progression.

Keywords: non-AIDS complications, HIV, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, risk factors

Introduction

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in the late 1990s has dramatically improved survival in HIV-infected patients, who now experience a growing burden of chronic comorbid diseases associated with aging, including diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is estimated that approximately 15% of HIV-infected individuals have comorbid DM.1, 2 The age- and body mass index (BMI)-adjusted rate of incident DM was over four times greater in HIV-infected cART-treated men, compared to HIV-seronegative men, in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. 1 Part of this increased risk has been attributed to cART and to hepatitis-C virus (HCV) co-infection. In the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs cohort,3 the incidence of diabetes increased with cumulative exposure to cART even after adjustment for traditional risk factors. In the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS), the study population for the current analysis, care in the cART era was independently associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of DM.4 HCV co-infection was also associated with a higher risk of DM in VACS.4

Considering the rising incidence of DM in the HIV population and the fact that DM accounts for approximately 45% of incident end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States (US),5 it is not surprising that diabetic nephropathy is increasingly identified on kidney biopsy in HIV-infected patients in the cART era. In the two largest kidney biopsy series among US adults with HIV, the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy was 5.3% and 6.7%, respectively.6, 7 Since many HIV-infected individuals with CKD never undergo a kidney biopsy, these figures likely underestimate the true prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in HIV-infected individuals.

There is also evidence to suggest that HIV and DM may have an additive effect on CKD progression.8 Choi et al examined the incidence of ESRD in a national cohort of over two million US veterans followed for a median of 3.7 years, stratified by race.8 After adjusting for age and gender, white veterans with DM had a 4-fold increase in risk of ESRD, and those with both HIV and DM had a 7-fold increase in risk of ESRD compared to those with neither diagnosis. A similar but magnified trend was observed in blacks. The primary objective of that study was to examine racial differences in ESRD rates, and the observations were not adjusted for other factors known to influence CKD progression, including CD4 cell count, HIV-RNA, cART use, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) use, or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).8 Careful adjustment for these important CKD risk factors is essential to determine the true impact of concomitant HIV infection and DM on the risk of CKD. The goal of the current study was to evaluate the individual and combined contributions of HIV and DM to CKD progression, adjusting for other important CKD risk factors.

Methods

The VACS Virtual Cohort has been described in detail previously. Briefly, it is a periodically updated observational cohort identified from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases, consisting of HIV-infected veterans and a 2:1 sample of age, sex, race, and site-matched HIV-uninfected veterans who have received medical care at a VA health care facility.9 Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the current study were age 18 to 80 years, a minimum of two outpatient serum creatinine results at least 90 days apart, and a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥ 45ml/min/1.73m2. Patients on chronic dialysis or with a history of kidney transplantation were excluded. We also excluded patients who had a diagnosis of acute kidney injury (N=650) or CKD (N=848) documented in the medical record at the time of enrollment. Only outpatient creatinine results were utilized to minimize the impact of acute kidney injury related to intercurrent illness. Baseline was defined as the day of VACS enrollment.

Demographics, morbidity and mortality data were obtained from the National Patient Care Database (Austin, TX). HIV status was established at baseline using the VA Immunology Case Registry of all HIV-infected veterans in care. Diabetes and comorbid conditions were defined at baseline using International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes from hospitalizations and outpatient visits within 12 months before or 6 months after enrollment as previously described.9, 10 To be considered present, two separate outpatient codes or one inpatient code were required. As previously described,2 a subject was considered to have DM if any one of the following criteria was met: (a) glucose > 200 mg/dl on two separate occasions, (b) ICD-9 code for DM and treatment with an oral hypoglycemic agent or insulin for > 30 days, (c) ICD-9 code for DM and glucose > 126 mg/dl on two separate occasions, or (d) glucose > 200 mg/dl on one occasion and treatment with an oral hypoglycemic or insulin for > 30 days. Laboratory data were extracted from the integrated electronic medical record. Receipt of individual antiretroviral agents (ARVs) was determined from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. cART was defined as the combination of at least three ARVs, excluding low dose ritonavir. Cumulative exposure to individual ARVs that have been associated with increased CKD risk (tenofovir, indinavir, atazanavir, and lopinavir)11 and to ACEI or ARB was assessed in years using pharmacy fill data. Adherence to prescribed ARVs was estimated using pharmacy fill data as previously described in the VACS virtual cohort.12 Briefly, adherence was calculated using the algorithm of Steiner and colleagues13 as the sum of days supply for a given period/sum of days in refill intervals for that period.

Eligible subjects were divided into four groups based on DM and HIV status at baseline. Race was categorized as black or non-black. eGFR was calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.14 Baseline eGFR, CD4 cell count, HIV-RNA, and HbA1c were determined using a baseline window spanning VACS enrollment date ± 180 days. HIV-RNA was log10 transformed and CD4 cell count was square root transformed in all regression analyses. The closest recorded value to enrollment was considered as the baseline value. History of AIDS-defining illness was defined at baseline.

The primary endpoint was an eGFR < 45 ml/min/1.73m2, confirmed on two outpatient measurements of serum creatinine at least 90 days apart. This endpoint was selected because age- and gender-adjusted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rise steeply when eGFR falls below this level.19 For consistency with prior studies, we also performed a sensitivity analysis based on eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2.

Descriptive analyses were stratified by HIV and DM status. Variables of interest were compared among the groups using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Those that approached significance were entered into multivariable Cox proportional hazard models to allow comparison of time to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 among the study groups. Two-tailed P values <0.05 were considered significant. Separate sensitivity analyses were performed after excluding subjects with a new diagnosis of DM during the study period and after excluding subjects with a baseline eGFR between 45–59ml/min/1.73m2. In addition, we tested the impact of adjusting for the competing risk of death using the Fine and Gray method.15 Based on a recent report demonstrating an interaction between race and DM as predictors of ESRD in HIV-infected veterans,16 we also repeated the multivariable analysis after stratifying by black versus non-black race. In subgroup analysis restricted to HIV-infected veterans, we adjusted for potentially nephrotoxic ARVs, CD4 cell count, and HIV-RNA. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed after excluding HIV-infected veterans who never received cART, and after adjusting for a previously described index of ARV adherence.13 Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.1.3 (Cary, NC) and STATA, version 11 (College Station, TX). The VACS Virtual Cohort was approved by the Human Investigation Committee at the Yale School of Medicine and the VA Connecticut Human Subjects Subcommittee.

Results

A total of 31,072 eligible veterans were divided into four disease groups based on their HIV and DM status at baseline (HIV only, DM only, HIV and DM, and neither diagnosis). Among HIV-infected subjects, those who also had DM had slightly higher CD4 cell count and lower HIV-RNA (Table 1). They also had a higher burden of comorbid disease, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and HCV co-infection, and were more likely to be prescribed an ACEI or ARB. Among subjects with DM, those who also had HIV infection had a lower HbA1c at baseline and were less likely to be prescribed ACEI/ARB or hypoglycemic agents. The number of available outpatient serum creatinine measurements was similar among subjects with either HIV or DM, and highest among those with both diagnoses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and kidney disease outcomes, stratified by HIV and diabetes status.

| Overall N=31073 | No HIV or DM N=13562 | DM only N=5088 | HIV only N=10626 | HIV and DM N=1796 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||||

| Mean age at baseline, years | 53 (10) | 52 (10) | 57 (9) | 51 (10) | 56 (9) |

| Male gender (%) | 97 | 97 | 98 | 97 | 98 |

| Black race (%) | 45 | 43 | 47 | 46 | 49 |

| Median follow-up, years (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 4.7 (2.8, 6.7) | 5.4 (3.4, 7.0) | 4.4 (2.5, 6.4) | 5.1 (3.1, 7.0) |

| Co-morbidities at baseline | |||||

| Hypertension (%) | 34 | 35 | 61 | 18 | 45 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 7 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 10 |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Hepatitis C infection (%) | 21 | 14 | 14 | 31 | 39 |

| Hepatitis B infection (%) | 2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 4 | 3 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 52 | 48 | 62 | 51 | 64 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 15 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 17 |

| Drug use (%) | 14 | 12 | 8 | 18 | 17 |

| Median CD4 count at baseline1, cells/m3 | 319 (126, 523) | - | - | 314 (126, 517) | 355 (128, 586) |

| Median HIV-RNA at baseline1, log10 copies/mL | 4 (3, 5) | - | - | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 5) |

| cART use at baseline (%), among HIV+ | 21 | - | - | 21 | 21 |

| Nephrotoxic ARV use during follow-up | |||||

| Atazanavir use (%) | 21 | - | - | 21 | 21 |

| Indinavir use (%) | 7 | - | - | 6 | 9 |

| Lopinavir use (%) | 23 | - | - | 23 | 22 |

| Tenofovir use (%) | 23 | - | - | 23 | 24 |

| Mean HbA1c at baseline2, % of total | 7.7 (2.2) | - | 7.9 (2.2) | - | 7.3 (2.2) |

| ACEI/ARB use at baseline (%) | 40 | - | 84 | - | 72 |

| Mean eGFR at baseline, ml/min/1.73m2 | 94 (19) | 92 (18) | 91 (19) | 98 (19) | 95 (20) |

| eGFR ≥60 at baseline (%) | 94 | 95 | 92 | 93 | 89 |

| Mean number of eGFR measures | 18 (18) | 13 (13) | 22 (20) | 20 (17) | 32 (26) |

| eGFR < 45 during follow-up, n (%) | 2213 (7.1) | 480 (3.5) | 597 (11.7) | 812 (7.6) | 324 (18.0) |

| Mortality (%) | 9 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 17 |

Data are reported as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or %. DM, diabetes mellitus; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral agent; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, glomerular filtration rate estimated using the CKD-EPI formula; mortality, proportion of subjects who died during the analysis period.

Among 12423 subjects with HIV, 32% were missing data on baseline CD4 count and 28% were missing data on baseline HIV-RNA.

Among 6884 subjects with DM, 32% were missing data on baseline HbA1c.

Rate of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 by HIV and DM status

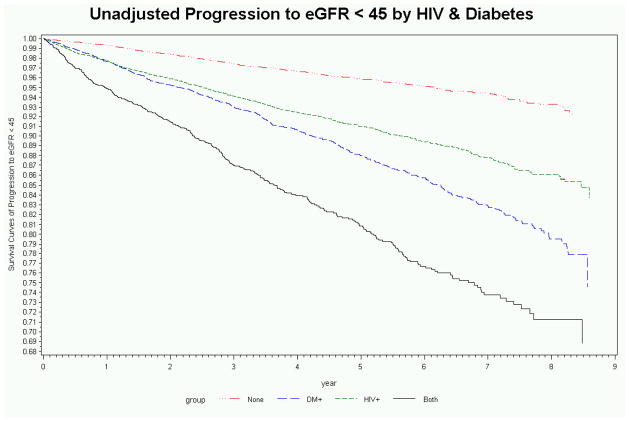

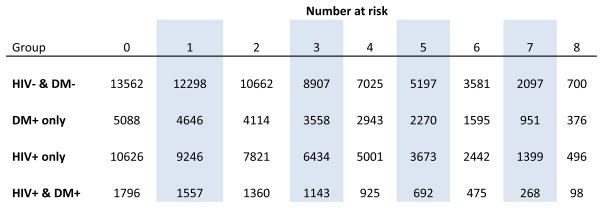

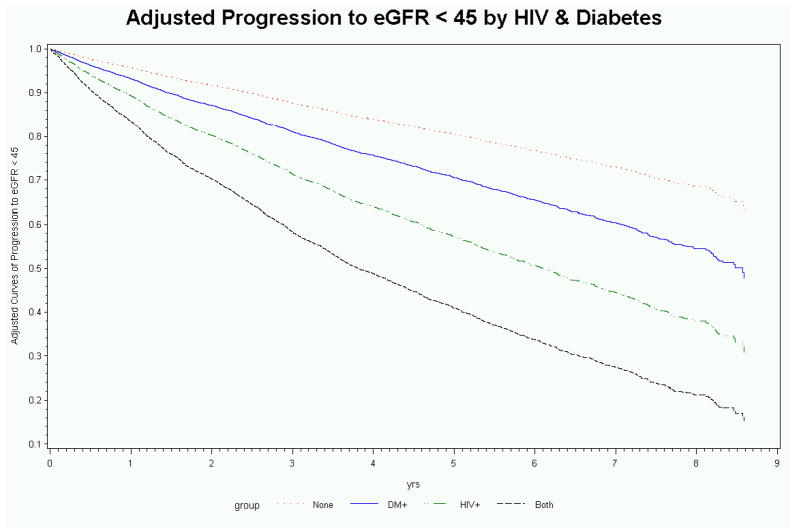

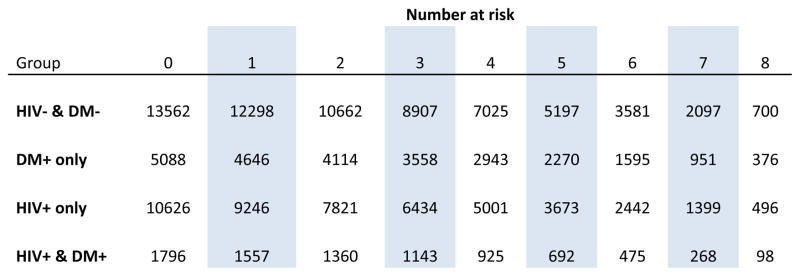

Over a median follow-up of 5 years (interquartile range: 3 to 7 years), 7% of subjects progressed to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2, ranging from < 4% in those without HIV or DM to 18% in those with both HIV and DM (Table 1). When compared to the rate of CKD progression in subjects without HIV or DM (0.85/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.78–0.93), the unadjusted rate of CKD progression was higher in subjects with HIV only (1.95/100 person-years, 95% CI 1.59–2.38), DM only (2.64/100 person-years, 95% CI 2.14–3.25), and both HIV and DM (4.37/100 person-years, 95% CI 3.47–5.50) (Figure 1). Although subjects with DM were older, among diabetics the median age at progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 was similar in those with and without comorbid HIV (61 versus 63 years).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted (a) and adjusted (b) rates of progression to estimated glomerular filtration rate < 45ml/min/1.73m2 stratified by HIV and diabetes.

Adjusted hazard ratios for progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 by HIV and DM status

After adjusting for demographics and traditional CKD risk factors, the hazard ratio for CKD progression was similar in subjects with HIV or DM only, and highest among those with both HIV and DM (Table 2). Lower baseline eGFR, increasing age, black race, HCV co-infection, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and alcohol abuse were also independently associated with increased risk of CKD progression (Table 2). Baseline eGFR was a strong independent predictor of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2; 27% of progressors and 5% of non-progressors had a baseline eGFR between 45–59ml/min/1.73m2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 in multivariate analysis

| VACS VirtualCohort Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Veterans with HIV Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Veterans with Diabetes Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | |||

| No DM or HIV | Referent | -- | -- |

| DM only | 2.48(2.19, 2.80) | -- | Referent |

| HIV only | 2.80(2.50, 3.15) | Referent | -- |

| HIV and DM | 4.47(3.87, 5.17) | 1.78 (1.49, 2.12) | 1.81 (1.51, 2.18) |

| Baseline eGFR (per 5 ml/min/1.73m2) | 0.86 (0.85, 0.87) | 0.88 (0.86, 0.90) | 0.83 (0.81, 0.85) |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.35 (1.28, 1.42) | 1.32 (1.20, 1.44) | 1.23 (1.11, 1.36) |

| Black race | 1.38 (1.26, 1.51) | 1.23 (1.05, 1.45) | 1.07 (0.90, 1.26) |

| Hypertension | 1.45 (1.32, 1.59) | 1.39 (1.17, 1.66) | 1.59 (1.32, 1.93) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.43) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.34) |

| Congestion heart failure | 2.58 (2.10, 3.16) | 2.26(1.42, 3.59) | 2.03 (1.46, 2.81) |

| Hepatitis C virus co-infection | 1.55(1.41, 1.72) | 1.42 (1.21, 1.66) | 1.62 (1.31, 1.99) |

| Hepatitis B virus co-infection | 0.85 (0.61, 1.17) | 0.76 (0.50, 1.15) | 0.65 (0.24, 1.76) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) |

| Alcohol use | 1.39(1.20, 1.60) | 1.49(1.15, 1.92) | 1.27 (0.93, 1.72) |

| Drug use | 0.89 (0.76, 1.05) | 0.85 (0.65, 1.11) | 0.90 (0.64, 1.28) |

| AIDS-defining illness at baseline | -- | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) | -- |

| CD4 cell count* at baseline | -- | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | -- |

| HIV-RNA* at baseline | -- | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) | -- |

| cARTuse at baseline | -- | 0.94 (0.79, 1.13) | -- |

| Hemoglobin A1c at baseline | -- | -- | 1.12 (1.09, 1.16) |

| ACEI or ARB exposure (per year) | -- | -- | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) |

DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated by CKD-EPI equation; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

The square root of CD4 cell count and log10 of HIV-RNA were included in the regression models.

Stratified Analysis

Because we detected a significant interaction between HIV and DM (p<0.001), we repeated the primary analysis after stratifying by HIV status. DM remained associated with an increased rate of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 regardless of HIV status, although the effect size was larger among HIV-negative veterans (adjusted HR 2.43, 95% CI 2.14–2.75) than among HIV-infected veterans (adjusted HR 1.67, 95 CI 1.46–1.49). Other results were consistent with the primary analysis.

Although we did not detect a significant interaction between race and DM (p=0.21), other investigators have found that DM is a stronger predictor of ESRD in HIV-infected veterans of non-black race.16 In a separate analysis stratified by race, the risk of reaching an eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 was consistently increased in subjects with both HIV and DM, whether they reported their race as black (adjusted HR 4.67, 95% CI 3.80–5.74) or non-black (adjusted HR 4.26, 95% CI 3.47–5.23).

Sensitivity Analyses

In separate sensitivity analyses, the results of the primary analysis were similar after excluding 2,003 subjects with baseline eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2, and after excluding 2,512 subjects with incident DM during the follow-up period (data not shown). In a sensitivity analysis using a more conservative endpoint of eGFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2, there was a more than 3-fold increase in risk of CKD progression among subjects with either HIV (adjusted HR 3.51, 95% CI 2.89–4.27) or DM (adjusted HR 3.10, 95% CI 2.51–3.83). Similar to the results of the primary analysis, the hazard ratio for progression to eGFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2 was highest among those with both HIV and DM (adjusted HR 5.51, 95% CI 4.34–6.99). Other results were highly consistent with the primary analysis.

Subjects with both HIV and DM also had the highest mortality rates (Table 1). In addition, subjects who progressed to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 had an increased risk of mortality compared to those who did not (unadjusted HR 3.67, 95% CI 3.36–4.00). The results of the multivariable analysis were highly consistent after adjusting for the competing risk of death. In the competing risk analysis, veterans with both HIV and DM (adjusted HR 4.32; 95% CI 3.75–4.98) had a more than 4-fold increase in risk of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 compared to subjects with neither diagnosis, while subjects with either HIV (adjusted HR 2.65; 95% CI 2.37–2.96) or DM (adjusted HR 2.39; 95% CI 2.12–2.69) were at intermediate risk. Other results were also consistent with the primary analysis.

Subgroup analysis in HIV-infected veterans

In subgroup analysis restricted to 7,328 subjects with HIV infection and available data for baseline CD4 cell count and HIV-RNA, 711 subjects progressed to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 over 4.97 person-years of follow-up. Compared to those with missing data on CD4 cell count or HIV-RNA, HIV-infected subjects included in this subgroup analysis were similar with respect to race and history of cardiovascular disease, Hepatitis B co-infection, drug use, and ADI. Included subjects were older, had higher median eGFR, and were more likely to be on cART at baseline. They were also more likely to have a history of Hepatitis C co-infection and alcohol use, and less likely to have hypertension and dyslipidemia. Comorbid DM remained independently associated with increased risk of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 after additional adjustment for CD4 cell count, HIV-RNA, cART use, and history of AIDS-defining illness at baseline (Table 2). Older age, black race, HIV-RNA, hypertension, congestive heart failure, HCV co-infection, and alcohol abuse were also independently associated with increased risk of CKD progression. Cumulative exposure variables for the ARVs tenofovir, indinavir, atazanavir, and lopinavir were not significantly associated with CKD progression, and these variables were not included in the final model. In sensitivity analysis, the results were similar after adjusting for an index of ARV adherence based on pharmacy fill data,13 and after excluding 2,527 subjects who never received cART (data not shown). In a separate sensitivity analysis using a more conservative endpoint of eGFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2, DM remained associated with a significant increase in risk of CKD progression among subjects with HIV (adjusted HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.28–2.18).

Subgroup analysis in veterans with DM

In subgroup analysis restricted to 4,687 subjects with DM and available data for baseline HbA1c, 618 subjects progressed to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 over 4.71 person-years of followup. Compared to subjects excluded because of missing data, subjects included in this subgroup analysis were slightly older, less likely to be black, and had a lower median eGFR at baseline. They were more likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary artery disease, and were more likely to be taking ACEI/ARB at baseline. Included subjects were less likely to have a history of Hepatitis C, alcohol, or drug use. Comorbid HIV remained independently associated with increased risk of progression to eGFR < 45ml/min/1.73m2 after additional adjustment for HbA1c and cumulative exposure to ACEI or ARB (Table 2). Higher baseline HbA1c was also independently associated with CKD progression among diabetics, while cumulative exposure to ACEI or ARB did not significantly influence the relative risk of CKD progression. In a separate sensitivity analysis using a more conservative endpoint of eGFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2, HIV infection remained associated with a significant increase in risk of CKD progression among subjects with DM (adjusted HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.40–2.55).

Discussion

In this analysis of data from the VACS cohort, we have demonstrated a significant and graduated association between HIV and DM status and the risk of progression to eGFR<45ml/min/1.73m2, even after adjustment for other factors known to influence CKD progression. While these findings are consistent with previous studies in the VA population,8, 16 the current study expands on those findings by adjusting for important markers of HIV and DM disease severity and treatment, suggesting that concurrent HIV and DM have a greater effect on the risk of CKD progression than would be expected from either disease alone. These results suggest that patients with both HIV and DM may benefit from more frequent screening for CKD, more rigorous follow-up of existing CKD, and more aggressive management of CKD risk factors. This hypothesis should be evaluated in future research studies.

The prevalence of eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 among the HIV-infected subjects in our study was similar to other studies in HIV-infected veterans,16, 17 including an earlier analysis of the VACS virtual cohort.18 We selected a more conservative endpoint of eGFR < 45 ml/min/1.73m2 because age- and gender-adjusted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rises steeply when eGFR falls below this level.19 We also required a minimum of two outpatient measurements of serum creatinine at least 90 days apart in order to confirm eGFR < 45 ml/min/1.73m2. In addition to the strength of our primary endpoint, the robust prescription data available in the VACS virtual cohort allowed us to adjust for cumulative exposure to ARV agents that have been associated with increased risk of CKD and to consider the influence of ARV adherence among HIV-infected subjects.

Despite the strengths of our study, the findings should be interpreted in light of several important limitations. First, baseline data on HIV-RNA, CD4 cell count and HbA1c were missing in nearly one-third of subjects with HIV or diabetes, respectively. Second, HbA1c may underestimate the degree of hyperglycemia in HIV-positive individuals. {Kim et al., 2009, Diabetes Care, 32, 1591–3} {Glesby et al., 2010, Antivir Ther, 15, 571–7} This may have limited our ability to fully account for the severity of DM in HIV-positive veterans, which would be expected to inflate the observed effect size for HIV in models including HbA1c. Third, we were unable to explain why DM was associated with a smaller increase in the rate of CKD progression among HIV-infected veterans, compared to uninfected veterans. It is notable that veterans with both HIV and DM had the highest frequency of outpatient eGFR measurements, which would be expected to bias our results towards an increased rate of eGFR decline in that group. Interestingly, the effect of DM has also been shown to be smaller than expected in studies of cardiovascular disease among HIV-infected individuals. {Worm et al., 2009, Circulation, 119, 805–11} Fourth, we were unable to assess the baseline prevalence or change in proteinuria over time. Since proteinuria is a prominent feature of both HIV-associated and diabetic nephropathy, this may lead to residual confounding. In particular, it is possible that the lack of benefit observed with ACEI/ARB therapy in our population reflects increased use of these agents in individuals with proteinuria, an important predictor of CKD progression.16 Finally, our findings may be less generalizable to women and demographically dissimilar populations.

In conclusion, DM and HIV are each risk factors for CKD. After adjustment for traditional risk factors for CKD progression and for competing risk of death, patients with both HIV and DM are at increased risk of CKD progression when compared to patients with only HIV or DM. Although not the focus of this analysis, other common comorbidities such as hypertension and HCV co-infection were also independently associated with increased risk of CKD progression in HIV-infected individuals. In order to optimize CKD screening and management in this population, future studies should determine the relative contribution of cumulative comorbidity, as well as the accompanying burden of polypharmacy, to the risk of CKD in HIV-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The Veterans Aging Cohort Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (U01 AA13566) and by the Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. This work was also supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (P01DK056492, R01DK088541, R01DK078897, and K23DK077568).

References

- 1.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1179–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. AIDS. 2009;23:1227–1234. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832bd7af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Wit S, Sabin CA, Weber R, et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1224–1229. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt AA, Fultz SL, Kwoh CK, Kelley D, Skanderson M, Justice AC. Risk of diabetes in HIV infected veterans pre- and post-HAART and the role of HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2004;40:115–119. doi: 10.1002/hep.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.System USRD. USRDS 2010 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berliner AR, Fine DM, Lucas GM, et al. Observations on a Cohort of HIV-Infected Patients Undergoing Native Renal Biopsy. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:478–486. doi: 10.1159/000112851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1145–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, Bertenthal D, Volberding PA, O’hare AM. Racial Differences in End-Stage Renal Disease Rates in HIV Infection versus Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, et al. Development and verification of a “virtual” cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006;44:S25–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223670.00890.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Justice AC, Lasky E, McGinnis KA, et al. Medical disease and alcohol use among veterans with human immunodeficiency infection: A comparison of disease measurement strategies. Med Care. 2006;44:S52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228003.08925.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2010;24:1667–1678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339fe53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braithwaite RS, Kozal MJ, Chang CC, et al. Adherence, virological and immunological outcomes for HIV-infected veterans starting combination antiretroviral therapies. AIDS. 2007;21:1579–1589. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281532b31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jotwani V, Li Y, Grunfeld C, Choi AI, Shlipak MG. Risk Factors for ESRD in HIV-Infected Individuals: Traditional and HIV-Related Factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, et al. Low rates of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1633–1639. doi: 10.1086/523729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer MJ, Wyatt CM, Gordon K, et al. Hepatitis C and the risk of kidney disease and mortality in veterans with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:222–226. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b980d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]