SUMMARY

Fanconi anemia (FA) is an inherited DNA repair deficiency syndrome. FA patients undergo progressive bone marrow failure (BMF) during childhood, which frequently requires allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The pathogenesis of this BMF has been elusive to date. Here we found that FA patients exhibit a profound defect in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that is present before the onset of clinical BMF. In response to replicative stress and unresolved DNA damage, p53 is hyperactivated in FA cells and triggers a late p21Cdkn1a-dependent G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest. Knockdown of p53 rescued the HSPC defects observed in several in vitro and in vivo models, including human FA or FA-like cells. Taken together, our results identify an exacerbated p53/p21 “physiological” response to cellular stress and DNA damage accumulation as a central mechanism for progressive HSPC elimination in FA patients, and have implications for clinical care.

INTRODUCTION

The hematopoietic system is tightly regulated to ensure the constitution of a stem cell pool during embryonic development and early post-natal life, and to maintain homeostasis throughout adult life. Multiple extrinsic and intracellular signals are integrated in the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) to regulate quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation into multiple lineages. Recently, the notion of cross-talk between pathways regulating the hematopoietic homeostasis and the DNA damage response (DDR) in HSPCs has emerged (Blanpain et al., 2011; Rossi et al., 2008; Seita et al., 2010). Specifically, there is substantial evidence that the tumor suppressor protein p53, its transcriptional target p21CDKN1A/CIP1/WAF1, and other S-phase regulators play an important role in regulating HSPC exit from the cell cycle, apoptosis or DNA repair, depending on the cellular context (Abbas and Dutta, 2009; Cheng et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2009; Milyavsky et al., 2010; Mohrin et al., 2010; Viale et al., 2009; Vousden and Prives, 2009). A p53-dependent response to accumulation of DNA damage and cellular stress has also been implicated in hematopoietic aging occurring throughout life, both under physiological conditions and in a number of DNA repair deficient in mice (Blanpain et al., 2011; Niedernhofer, 2008; Nijnik et al., 2007; Rossi et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2005). Interestingly, impairment of these control mechanisms can lead to genomic instability, progressive bone marrow failure and hematopoietic malignancies (Niedernhofer, 2008; Rossi et al., 2008).

Human acquired and inherited bone marrow failure (BMF) disorders are characterized by pancytopenia and hypocellular bone marrow occurring in patients during childhood. Although acquired aplastic anemia has been related to auto-immune mechanisms (Young, 2006), the pathophysiology of the most frequent inherited bone marrow failure syndrome, Fanconi anemia (FA), is still elusive (Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Shimamura and Alter, 2010). FA is caused by biallelic mutations of one of the fifteen FANC genes, the products of which interact in the unique FA/BRCA pathway in response to cellular stress and DNA damage during S phase to maintain genome integrity (de Winter and Joenje, 2009; Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Moldovan and D'Andrea, 2009). Although the precise biochemical functions of the FA/BRCA pathway are still unclear, there is substantial evidence that it promotes proper homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA repair (Deans and West, 2011; Kee and D'Andrea, 2010). The FA/BRCA pathway is also involved in the regulation of mitosis and cytokinesis to prevent micro-nucleation and chromosome abnormalities (Chan et al., 2009; Naim and Rosselli, 2009; Vinciguerra et al., 2010). FA cells are also uniquely hypersensitive to oxidative stress and apoptotic cytokine cues, including IFN-γ and TNF-α (Pang and Andreassen, 2009). FA cells show spontaneous and interstrand cross linker-induced chromosome fragility, a feature that is important for diagnosis in patients. Patients with FA frequently display developmental abnormalities, including short stature, a triangular face and thumb abnormalities (Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Shimamura and Alter, 2010). They undergo progressive bone marrow failure (BMF) during childhood, which frequently requires allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (Gluckman and Wagner, 2008; Kutler et al., 2003; Shimamura and Alter, 2010). FA patients also experience a strong predisposition to clonal evolution and cancer, especially myelodysplasia (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Bagby and Meyers, 2007; Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Kutler et al., 2003; Quentin et al., 2011; Soulier, 2011).

Attempts to uncover the mechanisms leading to BMF in FA patients have been unsuccessful to date, largely because of practical difficulties associated with studying a rare human disorder with low bone marrow cells in patients, and because murine Fanc-/- models do not fully recapitulate the phenotype of human FA (Parmar et al., 2009). The efficiency of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant in FA patients shows that BMF is primarily related to an intrinsic defect of hematopoietic cells. Here, we analyzed a large series of primary bone marrow samples from FA patients and developed in vitro and in vivo functional models to evaluate HSPC capacity in human FA cells. Consistent with the constitutive DNA repair defect of FA cells and with a general role of the p53 axis in HSC maintenance, we uncovered a pathophysiological mechanism for BMF in Fanconi anemia, in which HSPCs from FA patients are impaired due to p53/p21 activation and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in response to replicative stress and accumulating DNA damage. We found that this process begins prenatally during the formation of the HSPC pool. Knockdown of p53 rescued the HSPC defects and clonogenic ability in several in vitro and in vivo models, including Fancd2/p53 mice and a xenograft model involving transfer of human FA-like cord blood cells into immunodeficient mice. Our data highlight the role of an exacerbated ‘physiological’ DNA damage response due to a constitutive defect of DNA repair as a central mechanism of BMF in FA patients. More generally, these findings point to p53 activation due to unresolved cellular conflicts as a common unifying signaling mechanism for BMF syndromes.

RESULTS

Progressive impairment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in FA patients

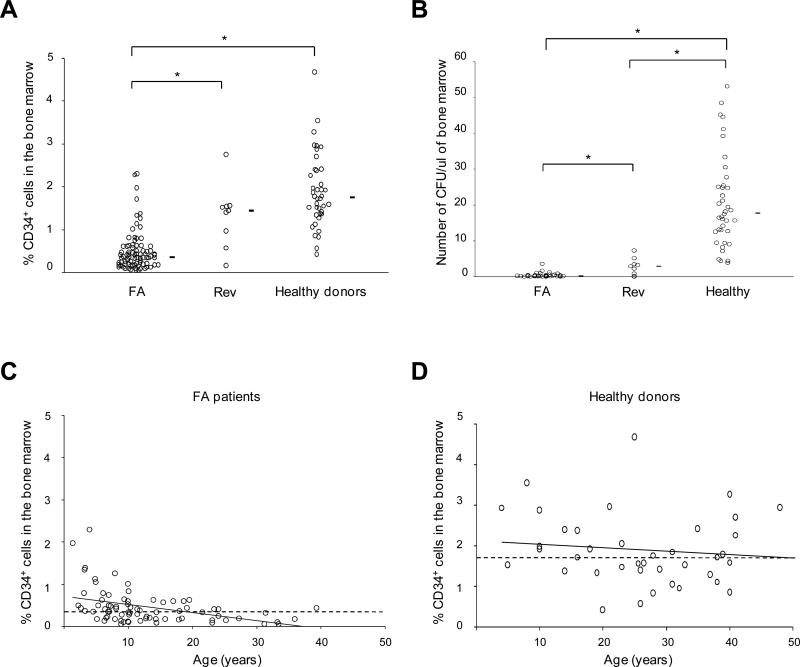

To investigate BMF in FA, we analyzed bone marrow samples from a cohort of 91 FA patients as compared to 40 healthy donors. CD34+ cell numbers were lower in the FA patients (Figure 1A), even in those who were diagnosed before BMF onset (FA siblings or severe congenital syndrome). When evaluated by methylcellulose colony-forming unit assays, the clonogenicity of bulk bone marrow cells or CD34+ cells for CFU-GM from the patients was very low to non-detectable (Figure 1B and Figure S1 available online). One feature of FA is the possible onset of spontaneous genetic reversion in hematopoietic cells, which can correct the FA phenotype and lead to somatic mosaïcism (Waisfisz et al., 1999; Soulier et al., 2005). Interestingly, FA patients with somatic mosaicism from our cohort (N = 9) had higher CD34+ cell counts and clonogenicity, showing that reversion of the FA/BRCA pathway defect can partially rescue hematopoiesis (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Impairment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and worsening with age in FA patients.

(A) CD34+ cell percentages in fresh bone marrow samples of 82 FA patients (FA), 9 FA patients with genetic reversion and somatic mosaicism (Rev), and 40 non-FA healthy donors. Mean values are indicated by horizontal bars. Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon test (*; FA vs healthy donors, P< 10-15; FA vs Rev, P< 10-4; Rev vs healthy donors, non significant). (B) CFU-GM assays (CFU) using fresh bone marrow cells from 47 FA, 9 Rev patients, and 40 healthy donors (*; FA vs donors, P< 10-15; FA vs Rev, P< 10-3; Rev vs donors, P< 10-4). (C) Bone marrow CD34+ cell percentages according to age in FA patients (N = 82) and (D) healthy donors (N = 40). For clarity, data from FA patients with genetic reversion (somatic mosaicism) are not indicated here. The dashed line indicates the median value in FA patients (0.40%) and in healthy donors (1.75%), the solid line indicates the trend according to aging. See also Figure S1.

We then ordered the CD34+ cell numbers in FA and healthy donors by age. Strikingly there was an additional progressive, aged-related, decrease to almost zero CD34+ counts in FA but not in healthy donors, consistent with the clinical worsening of the BMF during childhood (Figure 1C and 1D).

Collectively, these data suggest that FA subjects have an impairment of hematopoiesis that begins early, worsens through life, and results in overt BMF during childhood.

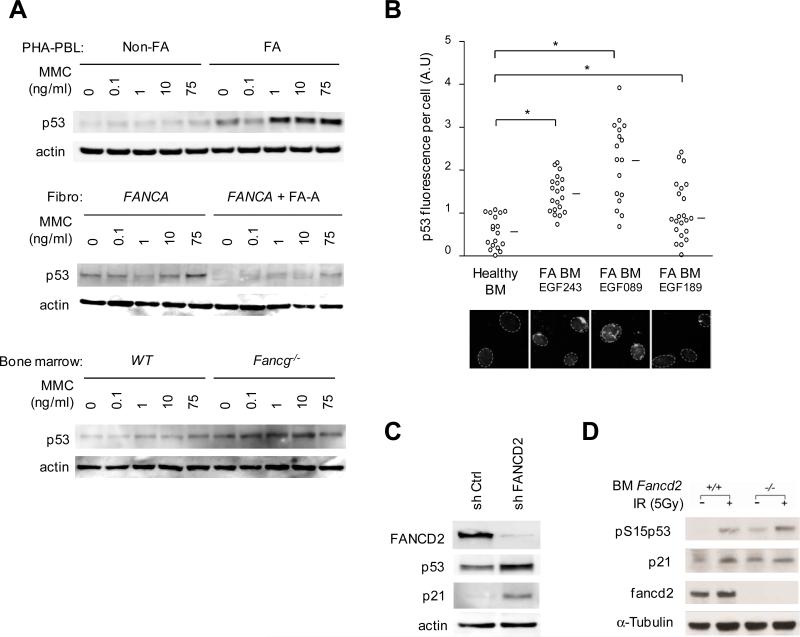

Constitutive induction of p53 in FA cells

FA cells have an intrinsic defect in the FA/BRCA pathway that is involved in the cellular response to DNA damage, particularly during DNA replication and during mitosis (Chan et al., 2009; de Winter and Joenje, 2009; Moldovan and D'Andrea, 2009; Naim and Rosselli, 2009; Pang and Andreassen, 2009; Vinciguerra et al., 2010). The progressive BMF seen in FA patients suggests that accumulation of endogenous stress and DNA damage participates to hematopoietic impairment. The protein p53 plays a central role in the response to stress and DNA damage and it has been involved in HSPCs maintenance (Blanpain et al., 2011; Milyavsky et al., 2010; Rossi et al., 2008; Vousden and Prives, 2009). Overexpression of p53 has been reported in FA EBV-immortalized cell lines and mouse cells, but a link to BMF has not been established (Kruyt et al., 1996; Kupfer and D'Andrea, 1996; Freie et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007). Here, we analyzed p53 activation in primary FA samples and found strong basal as well as Mitomycin C (MMC)-induced p53 protein expression in primary blood cells from 11 unrelated FA patients, primary skin fibroblasts from 2 FA patients, and bone marrow cells from Fancg-/- mice (Figure 2A). Moreover, we found a spontaneous increase in p53 staining in primary bone marrow cells from 7 FA patients as compared to 3 healthy donors (Figure 2B). Of note, oxidative stress also strongly induced p53 in FA cells (Zhang et al., 2005). To confirm that the p53 induction was directly related to the FA/BRCA pathway defect, we designed FA-like human 293T cells using short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of FANCD2, a key target of the FA pathway, and observed p53 as well as p21 induction in these cells (Figure 2C). In addition, we also observed hyperactivation of p53 in murine Fancd2-/-bone marrow cells in the presence or absence of exogenous DNA damage (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Constitutive p53 induction in FA cells.

(A) Representative immunoblot analysis of phytohemagglutinin-stimulated blood lymphocytes (PHA-PBL, top panel; PHA-PBL from 11 FA patients were tested with consistent results) and primary fibroblasts from FA patients (fibro FANCA), and bone marrow cells of Fancg-/- mice. Controls were PHA-PBL from healthy donors (Non-FA), FANCA-deficient human fibroblasts that were corrected by retroviral complementation (+FA-A), and wild-type (WT) littermate mice. Cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of Mitomycin C (MMC) as indicated. (B) Top panel, quantification of p53 fluorescence signal in individual bone marrow cells. Each circle represents a single cell; data from 3 representative FA patients (referred by unique EGF identification number) and a healthy donor are shown. Lower panel, representative microscopy images of p53 staining. Circles indicate nuclear contours; mean values are indicated by a horizontal bar and statistical analyses were performed using the Student test (*, P< 10-4, 10-4 and 10-2 in Healthy donor vs FA patient EGF243, EGF089 and EGF189, respectively). A.U., arbitrary unit; original magnification, × 63. (C) Immunoblot analysis of p53 and p21 protein levels in human 293T cells after transduction with sh Ctrl or sh FANCD2 shRNAs. (D) Immunoblot analysis of phospho-S15-p53 and p21 protein levels in murine wild-type (WT) and Fancd2-/- bone marrow cells. Cells were irradiated as indicated.

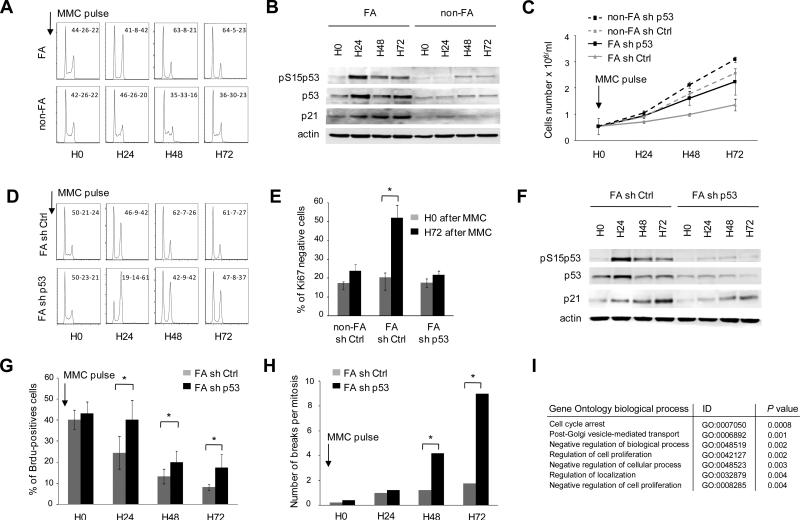

P53/p21 activation due to unresolved DNA damage triggers a late G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in FA cells after resolution of an early G2 arrest

To mimic the response of FA cells to endogenous DNA damage and analyze a potential link to the progressive cell impairment observed in patients, we briefly exposed EBV-immortalized FA cells to interstrand cross-linking agents (Mitomycin C) and analyzed the cellular response at several time-points. Non-FA controls cells were largely unaffected by the MMC pulse, but FA cells displayed a classical excess G2 arrest at 24h (Figure 3A) (Seyschab et al., 1993). Strikingly, at later time-points, we noticed that the G2-arrest resolved and the cells shifted into G0/G1 with S phase extinction (Figure 3A). This phenotype was only observed in FA cells, together with a strong p53 and p21 induction (Figure 3A and 3B). To investigate the consequences of p53 induction in FA cells, we knocked down p53 using shRNA (Figure 3C-3H). We found that p53 depletion in FA cells limited the level of growth inhibition elicited by a brief exposure to MMC (Figure 3C). This change was not caused by inhibition of the early G2 arrest or apoptosis (Figure 3D and S2A). However, in p53-silenced FA cells, p21 induction, G0/G1 accumulation, and inhibition of BrdU incorporation were less marked relative to control FA cells, while genomic instability was dramatically increased (Figure 3D-3H). Consistently, large scale gene expression analysis of p53-silenced relative to control FA cells 72h after the MMC pulse identified a cell-cycle arrest signature that was diminished by p53 silencing (Figure 3I). In addition, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments in FA cells showed that p53 was preferentially recruited to the promoters of p21 (CDKN1A) and GADD45a, two genes involved in G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest, but not of BAX, a gene controlling apoptosis, in agreement with low level of apoptosis in these EBV-immortalized cells (Figure S2A and S2B).

Figure 3. Unresolved DNA damage triggers a p53/p21 response which restricts the cell cycle into G0/G1 in FA cells.

(A) Cell-cycle analysis in FA EBV cells relative to non-FA EBV cells. After MMC pulse, FA cells displayed an early FA-prototypical arrest in G2. At later time-points and after resolution of the G2 checkpoint, FA cells shifted to arrest in G0/G1 with S phase extinction. G0/G1-S-G2 relative percentages are indicated for each panel. (B) p53, phospho-S15-p53, and p21 immunoblot analyses of FA and non-FA cell extracts at several time-points after the MMC pulse. (C) FA EBV cell lines were transduced with sh Ctrl or sh p53 shRNAs, GFP+ cells were sorted, cultured for 24 h, and grown for 3 days in MMC-free medium after a MMC pulse. Live cell numbers are shown at time-points 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. A non-FA EBV cell line transduced with sh Ctrl or sh p53 is shown as control. In the absence of MMC-pulse, sh Ctrl- or sh p53-transduced cell growth did not differ (not shown). (D) Cell-cycle analysis of FA cells shows a prototypical arrest in G2 of both sh Ctrl- and sh p53-transduced cells. G0/G1-S-G2 relative percentages are indicated for each panel. (E) Percentage of Ki67-negative cells in FA EBV cells transduced with sh Ctrl and sh p53 at H0 and H72 after MMC pulse. Statistical analyses were performed using the Chi–squared test for trend in proportions (*, P< 10-6). (F) p53, phospho-S15-p53 (pS15p53, activated), p21CDKN1A/CIP1/WAF1, and actin (loading control) immunoblot analyses of sh Ctrl- and sh p53-transduced EBV FA-cell extracts. (G) Quantification of the fraction of cycling sh Ctrl- and sh p53-transduced FA cells by BrdU incorporation. The strongly decreased percentages of cells in S phase after MMC treatment were lower in sh p53-transduced cells; statistical analyses were performed using the Odd ratio test (*, P<10-4). FA tests were performed in triplicates in at least two EBV FA cell lines. (H) Quantification of the genomic instability (chromosomal breaks per mitosis) in sh Ctrl- and sh p53-transduced EBV FA-cells. Statistical analyses were performed using the Chi–squared test for trend in proportions (*, P<10-12). (I) Top-ranked biological pathways which were differentially expressed in sh p53- relative to sh Ctrl-transduced EBV FA-cells at H72; significance values were determined by the hypergeometrical test using the 188 most differentially-expressed genes between p53-silenced and control cells. See also Figure S2.

Collectively, these data suggest that unresolved DNA damage in FA cells induces a p53/p21 response that restricts the cell cycle into G0/G1 after resolution of the G2 arrest, to limit deleterious DNA damage accumulation and preserve the genome integrity. Depletion of p53 partially rescues this phenotype by allowing a fraction of the cells to cycle and undergo replication, despite the increased genomic instability and G2 accumulation.

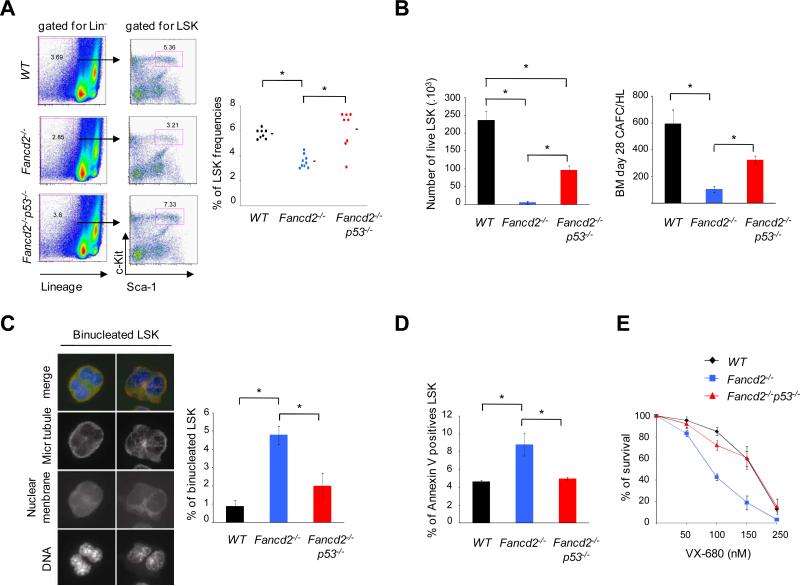

Fanc-/- mice have HSPCs defects that are rescued by p53 silencing

To further investigate the BMF mechanisms in FA, we performed experiments on two different FA mouse lines, Fancg-/- and Fancd2-/-. Although these mice do not develop spontaneous BMF, they exhibit subtle hematopoietic stem cell defects (Barroca et al., 2011; Parmar et al., 2010). We investigated whether the p53 response in FA cells could influence hematopoietic stem cell capacity in these mice. First, we generated double knockout Fancd2-/-p53-/-mice and analyzed their HSPCs. Strikingly, knockdown of p53 rescued the hematopoietic stem cell defects of Fancd2-/- mice with respect to LSK cell (Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+) numbers, clonogenicity, and proliferative and survival potential (Figure 4A and 4B). Second, we performed engraftment experiments using Fancg-/- bone marrow cells (Figure S3). Lin- cells were transduced with control or p53, shRNAs and subsequently re-injected in sub-lethally irradiated syngenic wild type mice (Figure S3A). We also designed a competitive engraftment assay in which Fancg-/- bone marrow lin- cells were transduced with a control-Cherry or p53-GFP shRNAs, sorted based on Cherry/GFP expression and co-transplanted (Figure S3B). In both experimental settings, p53-silenced cells engrafted better than controls (Figure S3).

Figure 4. Knockdown of p53 rescues the hematopoietic defects of murine Fancd2-/- bone marrow.

(A) Analysis of LSK (Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+) cell frequencies in the bone marrow; Fancd2-/- samples are compared to the wild-type (WT) and Fancd2-/-p53-/- samples, respectively. The left panel shows representative examples of flow cytometric plots of Sca-1 and c-Kit staining of lineage negative (Lin-) bone marrow. The right panel shows frequencies of LSK cells in the bone marrow as determined by flow cytometry. Mean values are indicated by horizontal bars; statistical analyses were performed using the t test (*, P<10-3 WT vs Fancd2-/- and Fancd2-/- vs Fancd2-/-p53-/- ; WT vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-, non significant). (B) Analysis of clonal growth of murine bone marrow HSPCs as determined by proliferation of isolated LSK cells in vitro for two weeks in presence of TPO and SCF (left panel), and Cobblestone area-forming cell (CAFC) frequencies of total bone marrow cells on FBMD1 stroma cells by day 28 (right panel). The data are mean from 3 mice per group; statistical analyses were performed using the t test (*; for proliferation, P<10-2 WT vs Fancd2-/- and Fancd2-/- vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-, P<0.05 WT vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-; for CAFC count, P< 0.05 WT vs Fancd2-/- and P<10-2 Fancd2-/- vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-; WT vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-, non significant). (C) Frequencies of binucleated cells in proliferating HSPCs. Bone marrow LSK cells were grown in culture for 48-72 h and stained for microtubules (red), nuclear membrane Lap2 (green) and DNA (blue) to determine the frequencies of binucleated cells. Representative images of binucleated LSK cells are shown in the left panel with original magnification, × 63. The data in the right panel are mean from 4 mice per group; statistical analyses were performed using the t test (*, P<10-3 WT vs Fancd2-/- and P<10-2 Fancd2-/- vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-; WT vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-, non significant). (D) Apoptosis of the bone marrow HSPCs as determined by Annexin V staining. Data are mean from 3 mice per group; statistical analyses were performed using the t test (*, P<0.05 WT vs Fancd2-/- and Fancd2-/- vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-; WT vs Fancd2-/-p53-/-, non significant). (E) Survival of bone marrow in presence of the cytokinesis inhibitor VX-680. Lin- cells from the bone marrow were cultured, exposed to VX-680 for 72 h, and cell survival was determined by counting live cells. The data are mean from 3-4 mice per group. See also Figure S3 and S4.

We and others recently reported a new role of the FA/BRCA pathway in monitoring cell cycle progression through mitosis and cytokinesis (Chan et al., 2009; Naim and Rosselli, 2009; Vinciguerra et al., 2010). Consistent with our previous study, murine Fancd2-/- bone marrow LSK cells exhibited a high rate of binucleated cells and apoptosis, a hallmark of cytokinesis failure (Figure 4C and 4D). These abnormalities were rescued in Fancd2-/-p53-/- mice showing that the cytokinesis failure observed was p53-dependent (Figure 4C and 4D). Moreover, we exposed Fancd2-/-lin- bone marrow cells to a cytokinesis inhibitor (VX-680) and found that such cells are hypersensitive compared to non-FA controls, again in a p53-dependent manner (Figure 4E and Figure S4).

Taken together, these experiments show that p53 impairs the hematopoietic and mitotic potential of Fanc-deficient murine HSPCs.

Silencing p53/p21 expression rescues human FA HSPCs capacities in in vitro and in vivo models

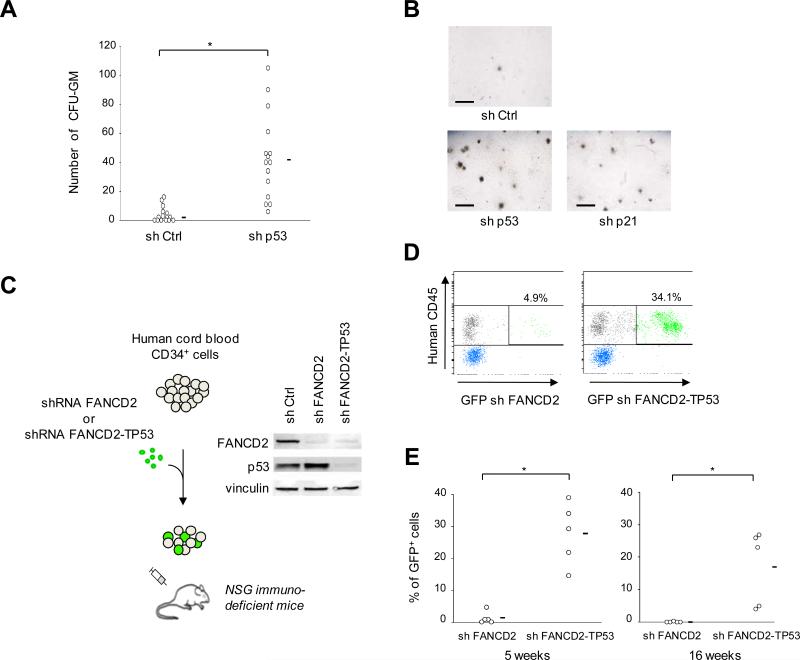

We next investigated whether inhibition of the p53/p21 response could improve HSPC function in human FA cells. CD34+ cells were sorted from fresh bone marrow samples from FA patients and lentivirally transduced with shRNA. Strikingly, depletion of p53 or p21 dramatically rescued in vitro clonogenicity of FA patients’ CD34+ cells in CFU-GM assays (Figure 5A and 5B; Table S1). Then, because the very low CD34+ cells numbers in FA patients did not allow efficient xenotransplant experiments, we used a surrogate model to analyze clonogenicity in vivo. We designed a xenotransplant assay using normal human cord blood CD34+ cells which were transduced with either a shRNA against FANCD2 (to obtain FA-like cells) or a tandem shRNA against FANCD2-TP53 (to simultaneously deplete FANCD2 and p53), and xenotransplanted them into Nod/Scid/IL2-R γc null (NSG) immunodeficient mice (Figure 5C). Strikingly, p53-silenced FA-like CD34+ cells engrafted dramatically better than the control FA-like cells (Figure 5D and 5E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the p53/p21 axis impairs the in vitro and in vivo clonogenicity of human FA HSPCs.

Figure 5. Silencing p53/p21 expression rescues FA hematopoietic progenitor cell capacities in human in vitro and in vivo models.

(A) CFU-GM assays using sh Ctrl- or sh p53-transduced CD34+ bone marrow cells from 14 FA patients. Colonies were counted 12 days after plating 500 CD34+ cells/well in 6-well plate, in duplicates. Mean values are indicated by horizontal bars. Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon test (*, P< 10-4). Complete data, and data from p21-silenced cells are shown in Table S1. (B) Representative examples of CFU-GM derived colonies from CD34+ cells of a given FA patient. Horizontal bar size = 1000 μm. (C) Design of human FA-like cell xenotransplant experiments. Human cord blood CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with sh FANCD2-GFP or tandem sh FANCD2-TP53-GFP, and injected into sub-lethally irradiated immunodeficient Nod/Scid/IL2-R γc null (NSG) mice. Immunoblot shows FANCD2 and p53 silencing efficiency. (D) Representative flow cytometry analysis of the proportion of donor human cells in mouse peripheral blood as quantified by HuCD45 staining 5 weeks post-transplant. The percentage of blood donor GFP+ cells (transduced cells) is indicated. (E) Chimerism post-xenotransplant of sh FANCD2- or tandem sh FANCD2-TP53-transduced human cord blood CD34+ cells, as assessed by GFP+ cell percentages on blood cell (5 weeks post-transplant, left panel) and bone marrow cell (16 weeks post-transplant, right panel). Each circle represents data from one mouse. Mean values are indicated by horizontal bars. Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test (*; at 5 weeks post-transplant, P = 10-2; at 16 weeks post-transplant, P<10-2). See also Table S1.

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and S phase extinction in FA HSPCs

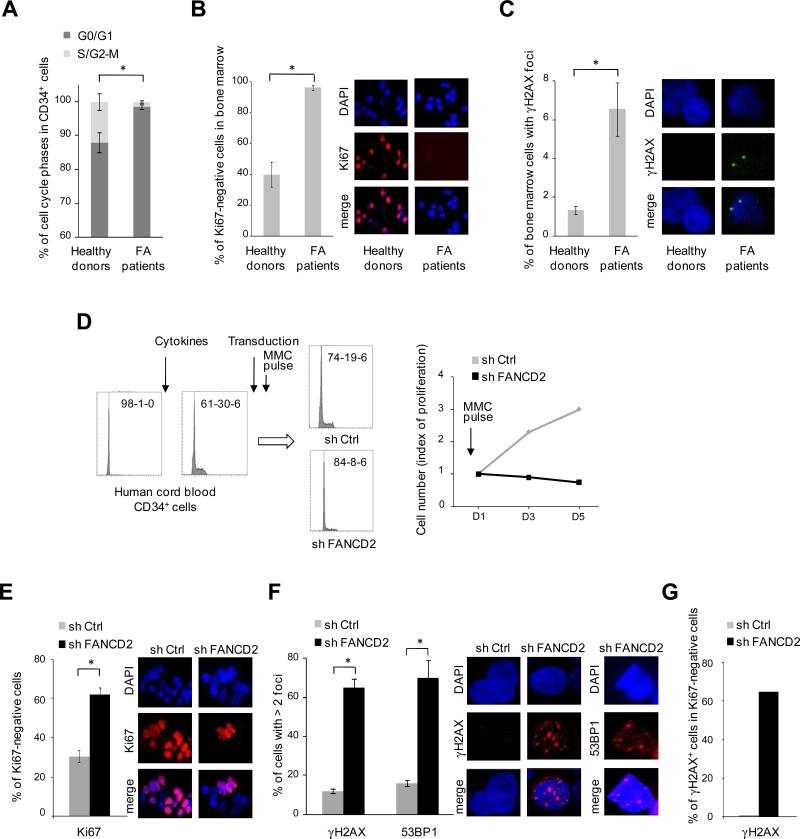

We then evaluated the cell cycle in HSPCs from FA patients. Fresh untreated CD34+ cells from 6 FA patients and 2 healthy donors were analyzed; strikingly, the percentage of cells in G0/G1 was higher in FA than in controls (Figure 6A). Moreover, total bone marrow cells from FA patients were massively arrested in G0/G1 and they showed a spontaneous increase of γH2AX staining (Figure 6B and 6C). To overcome the practical issues related to the rarity of CD34+ cells in FA patients, we used human healthy CD34+ cells transduced with FANCD2 shRNA and tested whether the accumulation of DNA damage can trigger G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in these human FA-like HSPCs. We sorted CD34+ cells from human cord blood and stimulated them to enter in S phase in ex-vivo culture (Figure 6D). Then, cells were transduced with control or FANCD2 shRNA, GFP sorted and briefly exposed to MMC. The control cells progressed through the cell cycle, but the FA-like CD34+ cells arrested in G0/G1 with S phase extinction, along with γH2AX and 53BP1 accumulation (Figure 6D-6G).

Figure 6. G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in FA HSPCs.

(A) Percentage of cell cycle phases in the CD34+ cells from 6 FA patients and 2 healthy donors (*; P< 10-4 for G0/G1; P< 10-4 for S/G2-M). Data in healthy donors were consistent with previous reports (Gothot et al., 1997). (B) Percentage of Ki67 negative cells in fresh bone marrow cells from 3 FA patients and 2 healthy controls (*, P< 10-4); representative microscopy images for Ki67 staining are shown. (C) Percentage of bone marrow positive cells for γH2AX staining (at least 1 foci) in 5 FA patients and 2 healthy donors (*, P< 10-2); representative microscopy images for γH2AX staining are shown. (D) Healthy human cord blood CD34+ cells were stimulated to enter in cell cycle by cytokines stimulation. After 24 h, cells were transduced by shFANCD2 or shCtrl. Three days later, GFP+ cells were sorted, briefly exposed to MMC (2 h at 100 ng/ml), grown for 5 days in MMC-free medium, and analyzed for cell cycle and proliferation. Cell cycle analysis is shown at time-point D5; G0/G1-S-G2 relative percentages are indicated for each condition. (E) Percentage of Ki67 negative cells from the experiment shown in (D) at D5 (*, P< 10-4). (F) Percentage of γH2AX and 53BP1 positive cells (*, P< 10-6 for γH2AX, and P< 10-5 for 53BP1). (G) Percentage of γH2AX positive cells within the Ki67 negative population. Data of (A), left panels of (D), and (G) were obtained by flow cytometry. Original magnification of microscopy images, × 63. For (A), (B), (C), (E) and (F), the mean value is shown; statistical analyses were performed using the Chi–squared test for trend in proportions.

p21 expression and cell-cycle arrest in embryonic and adult HSPCs from FA patients

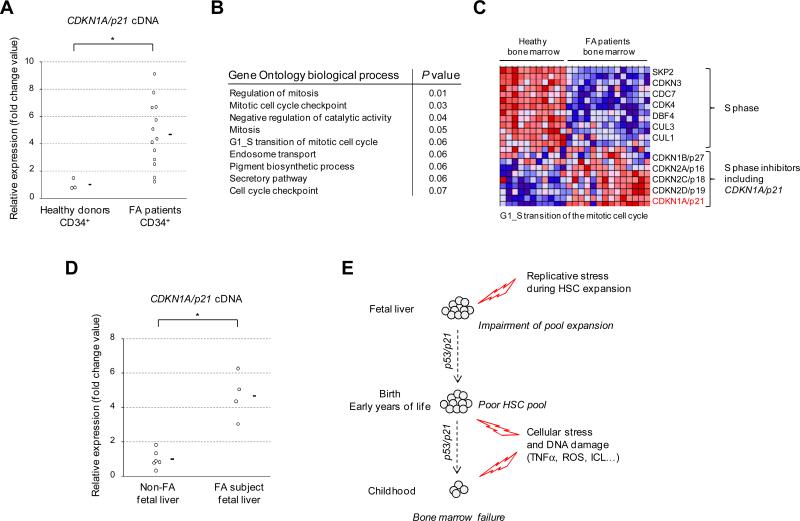

To confirm that FA patients have constitutive activation of a p53/p21 axis in their HSPCs in vivo (in addition to increased p53 in total bone marrow cells, Figure 2B), we evaluated the level of the p21 gene (also known as CDKN1A) expression by RT-qPCR in CD34+ cells sorted from fresh bone marrow samples of FA patients and healthy donors. We found that CDKN1A/p21 levels were higher in FA CD34+ cells (Figure 7A). We analyzed large-scale gene expression data of bone marrow cells from FA patients versus healthy donors. Gene pathways enrichment analysis ranked on top position signatures of cell cycle and mitosis arrest (Figure 7B and 7C), consistent with increased numbers of G0/G1 cell-cycle arrested cells in the bone marrow of FA patients. Notably, not only CDKN1A/p21 but also other cell cycle inhibitors like CDKN2A/p16 were induced in total bone marrow cells from FA patients (Figure 6C), whereas in CD34+ purified cells CDKN2A/p16 expression was undetectable (by RT-qPCR experiments, data not shown), suggesting that the downstream pathways may vary between HSPCs and more differentiated hematopoietic progenitor cells in patients (Blanpain et al., 2011).

Figure 7. P21 expression and cell-cycle arrest in embryonic and adult HSPCs from FA patients.

(A) CDKN1A/p21 gene expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR in bone marrow CD34+ cells from 13 FA patients and 3 healthy donors. Normalization was performed using the GUS reference gene. CDKN1A values are expressed by fold change relative to the mean expression in healthy donors which was arbitrary attributed to 1. Mean values are indicated by a horizontal bar. Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon test (*, P<10-2). (B) Top-ranked differentially expressed biological processes between FA and non-FA bulk bone marrow samples; Gene Ontology genesets were scored using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and P values were computed using 2000 permutations. The top-ranked GO biological processes are shown. (C) Hierarchical clustering and heat-map of gene expression in FA and non-FA bone marrow samples using the geneset G1_S_TRANSITION_OF_ MITOTIC_CELL_CYCLE. (D) CDKN1A/p21 gene expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR in liver samples from 4 human FA fetus and compared to 6 non-FA fetus from the same term (14-18 weeks of gestation). Normalization and representation of the expression data was performed like in (A). Statistical analyses were performed using the Student test (*, P< 10-3). For (A) and (D), RT-qPCR analysis were performed in an independent set of experiment and normalized to the expression of a second reference gene (ABL1) with consistent results (data not shown). (E) A model for bone marrow failure in FA.

Our data in bone marrow HSPCs from very young FA patients (Figure 1C) suggested that the hematopoietic impairment begins early in life. It is noteworthy that the formation of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) pool occurs largely during prenatal life, more specifically in human in the embryonic liver between 14 and 18 weeks of gestation. We hypothesized that such cells should experience massive replicative stress during the expansion stage leading to an activation of the p53/p21 axis in FA subjects. We analyzed CDKN1A/p21 gene expression in 4 FA fetal liver samples obtained between 14 and 18 weeks of gestation from medical abortion after FA prenatal diagnosis. Compared to 6 non-FA fetal liver samples from the same gestational stage, CDKN1A/p21 levels were dramatically overexpressed in the FA fetus (Figure 7D). Taken together with our other data, this suggests that replicative stress triggers an exacerbated p53/p21 response that impairs HSC pool during prenatal life in FA subjects. Additional progressive aged-related cellular stress and DNA damage would lead to HSPC exhaustion and to BMF during childhood.

DISCUSSION

Although FA is the most frequent cause of congenital BMF, its pathophysiological mechanisms have been elusive to date. Research has been hampered by the fact that Fanc-deficient mice do not spontaneously develop BMF (Parmar et al., 2009). Here we investigated primary bone marrow samples from a large series of FA patients and found a constitutional activation of a p53/p21 axis in FA HSPCs. This response was triggered in FA cells by unresolved cellular stress and DNA damage and leads to a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest after resolution of the early G2-arrest. The link with the development of an overt BMF in patients was shown using several in vitro and in vivo models, including an experimental protocol using FA-like cells that overcomes the practical difficulties associated with the lack of CD34+ cells from FA patients. Moreover, our data in very young FA subjects (before the development of a clinical BMF) and in human FA fetus strongly suggest that this process begins as early as prenatally during the formation of the hematopoietic stem cell pool.

The protein p53 is a key transcription factor that regulates several signaling pathways involved in the response to physiological signals, cellular stress, DNA damage and oncogene activation (Vousden and Prives, 2009). When activated, p53 accumulates and triggers expression of target genes that protect genomic integrity. These protective mechanisms include cell-cycle arrest and quiescence, DNA repair, initiation of senescence, or induction of apoptosis, depending on the cellular context (Blanpain et al., 2011; Rossi et al., 2008; Vousden and Prives, 2009). FA patients have a constitutively defect in the FA/BRCA pathway, leading to accumulation of replicative DNA damage, cytokinesis failure and cellular stress (e.g. ROS and TNFα) (Chan et al., 2009; Dufour et al., 2003; Moldovan and D'Andrea, 2009; Naim and Rosselli, 2009; Pang and Andreassen, 2009; Vinciguerra et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2005). The activation of the p53/p21 axis that we found in the HSPCs from FA patients is likely an exacerbated ‘physiological’ response to unresolved replication stress, endogenous DNA damage and cellular stress that accumulate throughout accelerated aging in FA (Neveling et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2008). Such progressive impairment of HSPCs by p53-related cell cycle arrest and apoptosis is consistent with the delayed onset and progressive feature of the BMF seen in FA patients. Our finding that very young FA patients exhibit an HSPC defect before the development of a clinical BMF and that the p53/p21 axis is activated in human fetal liver samples at the stage of massive HSC pool expansion suggest a model for BMF throughout life (Figure 7E). In this model, the formation of the HSC pool during fetal liver is hampered by replicative stress; after birth, the additional accumulation of cellular stress and unresolved DNA damage leads to progressive exhaustion of the remaining HSCs and clinical BMF.

Our findings have implications for the clinical care and therapeutic of FA patients. First, because excess of cellular stress and unresolved DNA damage accumulating throughout the life trigger HSPCs impairment through p53/p21 induction, it would be beneficial to limit such accumulation. In addition to prevention from exposure to exogenous DNA insults, patients might therefore benefit of new treatments aiming to inhibit proinflammatory cytokines or oxidative stress (Dufour and Svahn, 2008). Interestingly, it was recently shown that the FA/BRCA pathway counteracts the DNA inter-strand crosslink genotoxicity related to endogeneous aldehydes (by-products of cellular metabolism), and BMF might be mitigated if patients’ capacity for detoxifying aldehydes could be enhanced (Joenje, 2011; Langevin et al., 2011). Second, although direct targeting of p53 using small inhibitors (Gudkov and Komarova, 2010) might enhance HSPC progression through the cell cycle and ameliorate BMF, this approach would probably increase genomic instability and increase the risk of clonal evolution to malignancy. Third, regarding gene therapy which constitutes a promising option for FA patients (Tolar et al., 2011), our data suggest that HSPCs would need to be collected at as early an age as possible in to avoid accumulation of damage and exhaustion. More generally, whatever therapeutic options are pursued, it is likely that they will be more effective if started early in life. Finally, these concepts reinforce the view that allogeneic bone marrow transplant is a radical and curative therapy for BMF in FA patients, despite the risk of early and late complications (Gluckman and Wagner, 2008; Rosenberg et al., 2005).

A key feature of FA is a major predisposition to myelodysplasia and acute leukemia (Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Kutler et al., 2003; Quentin et al., 2011; Shimamura and Alter, 2010). FA patients frequently experience genetic clonal evolution which can lead to transformation in a multistep oncogenic manner. Interestingly, transformed FA cells frequently acquire attenuation of the response to DNA damage and cellular stress suggesting that p53 induction in FA also constitutes an anti-cancer barrier that has to be overcome during tumor progression (Ceccaldi et al., 2011; Li et al., 2007; Rani et al., 2008). In addition to attenuation of the DDR, we also found rare cases of p53 deletion in AML developing in FA patients (Figure S5). These concepts have important implications for developing MDS/AML treatments based on synthetic lethality by targeting specific DNA repair pathways in FA and, more generally, in non-FA patients (Chen et al., 2009; Helleday et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2009).

FA is the most frequent inherited cause of bone marrow failure (Dokal and Vulliamy, 2008; Shimamura and Alter, 2010). Interestingly, an elevated p53 response has been implicated in the pathogenesis of other constitutional BMF syndromes. In Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA), a constitutive defect in ribosome metabolism induces a p53-dependent response in the highly proliferative erythroid compartment, leading to massive apoptosis and neonatal anemia (Narla and Ebert, 2010; Zhang and Lu, 2009). In dyskeratosis congenita, constitutive defect in telomere metabolism and subsequent progressive telomere shortening triggers p53-induced senescence, leading to a delayed BMF in patients (Bellodi et al., 2010; Chin et al., 1999). Our findings in FA point to the idea that p53 activation due to unresolved cellular conflicts may be a common unifying signaling mechanism for congenital BMF syndromes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Patients and biological material collection

This study was based on the cohort of FA patients referred at Saint-Louis and Robert Debré Hospitals, Paris, French Reference Center for Constitutional Bone Marrow Failure. All patients had a FA diagnosis based on FA tests, including the chromosomal breakage test (Soulier et al., 2005). Informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their relatives. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institut Universitaire d'Hématologie at Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris. Biological samples from 91 FA patients, aged 1 to 40 years (median 10), were available from yearly FA follow-up. Samples from 40 healthy bone marrow donors, aged 4 to 48 years (median 26), were used as controls (Cell Therapy Unit, Hopital Saint-Louis). CD34+ cells from fresh bone marrow samples were purified using the MicroBead kit (Miltenyi). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–immortalized lymphoblastcell lines from FA patients were produced in our center and used at low passage. Human umbilical cord blood samples were collected from healthy full-term deliveries after maternal informed consent according to French authorities guidelines. FA fetus samples were obtained after medical abortion for FA prenatal diagnosis at 14-18 weeks of gestation; non-FA controls were fetus samples of the same term diagnosed with non relevant malformations. All fetus samples were obtained with written consent of the parents for research.

Functional in vitro tests in EBV cells

After lentiviral transduction of shRNA in FA EBV cell lines, GFP+ cells were sorted and cultured. The FA tests were performed, in triplicates, after 2-h MMC pulse (100 ng/mL) on growing cells, on at least two different EBV FA cell lines, in at least two independent experiments. For cell-cycle analysis, cells were treated with MMC, washed and cultured in MMC-free medium. At the indicated time-points, cells were fixed in chilled 70% ethanol, stored overnight at -20°C, washed with PBS and resuspended in propidium iodide. For BrdU experiments, cells were incubated with a 5-bromo2’-deoxy-uridine (BrdU) pulse (10 μg/ml) for 45 min at each time-point. Then, cells were washed and resuspended in culture medium for 2 h prior to be fixed in chilled 70% ethanol. Ratios of cycling cell were analyzed by FACS. Chromosomal breaks tests were scored on mitoses using conventional cytogenetic methods (Soulier et al., 2005).

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescent analyses

Antibodies were used against human p53 (D0-1, Santa Cruz), pSer15p53 (Cell Signaling), murine p53 (Calbiochem, clone PAb240), murine pSer15p53 (Calbiochem), Actin (Santa Cruz), human FANCD2 (Novus Biologicals), mouse Fancd2 (Parmar et al., 2010), p21 (Becton Dickinson), and vinculin (Abcam). Signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Pierce) and visualized with a Fuji LAS-3000 luminescent image analyzer system.

For immunofluorescent analysis, HSPCs were cytospun on slides, fixed, permeabilized, and subsequently stained for Ki67 (Abcam), γH2AX (Millipore), 53BP1 (Cell signaling) and p53 (D0-1, Santa Cruz).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using the p53 monoclonal antibody D0-1 (Santa Cruz) as described (Jackson and Pereira-Smith, 2006).

Murine bone marrow analysis

Fancg-/- mice were a kind gift of F. Arwert (Koomen et al., 2002). Fancd2-/-mice and Fancd2-/-p53-/- mice were generated as previously reported (Houghtaling et al., 2003; Houghtaling et al., 2005; Parmar et al., 2010). Murine bone marrow cells were harvested and stained for LSK cells as previously described (Parmar et al., 2010). For apoptosis detection, cells were stained with FITC-Annexin V (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software. LSK cells were FACS sorted and cultured in StemPro HSC medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) containing 40 ng/ml each murine stem cell factor (SCF) and murine thrombopoietin (TPO). For quantitation of binucleated cells, LSK cells were allowed to proliferate for 48-72 h and cytospun on slides. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized, and subsequently stained for microtubules, DNA and nuclear membrane Lap2 as described previously (Vinciguerra et al., 2010). To assess the toxicity of cytokinesis inhibition on bone marrow, Lin- cells were isolated using magnetic beads (Miltenyi) and cultured in presence of the VX-680 cytokinesis inhibititor (ChemieTek) in HSC medium. The cell survival was assessed by counting the live cells using trypan blue staining.

Gene silencing in human and murine hematopoietic cells

shRNAs targeting human FANCD2 (Ceccaldi et al., 2011), TP53 (Brummelkamp et al., 2002), CDKN1A/p21 (Berns et al., 2004), murine Trp53 (Dirac and Bernards, 2003), and Luc (Ctrl) were generated in the pTRIP/ΔU3-MND-GFP vector and transduced using lentivirus. The vector used to construct the tandem FANCD2-TP53 shRNA is a kind gift of Bruno Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium). A vector encoding the red fluorescent protein Cherry was derived from pTRIP/ΔU3-MND-GFP and a shRNA Luc was inserted. Cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 20% BIT (STEMCELL Technologies), stem cell factor, Flt3-ligand, IL-3 (R&D Systems Europe), and thrombopoietin (STEMCELL Technologies). Silencing efficiency was checked by specific immunoblot in all experiments.

Colony-forming Unit Granulocyte/Macrophage (CFU-GM) assays and Cobblestone area-forming cell (CAFC) assays

To evaluate CFU-GM colony numbers in human samples, 5×104 bulk bone marrow cells were plated in duplicate and cultured in MethoCult medium (Stem Cell Technologies) in 6-plate dishes. On day 14, CFU-GM were identified and counted using standard criteria. For CFU-GM assay combined with shRNA silencing, 500 CD34+ cells from FA patients were transduced over-night with sh Ctrl, sh p53 or sh p21. After resuspension in MethoCult medium and plated in 6-plate dishes in duplicate, and colonies were counted after 14 days.

For murine experiments, bone marrow cells were seeded in 12-plate dishes at a density of 7×104 cells/well in triplicate in mouse Methocult medium (Stem Cell Technologies). Hematopoietic colonies (CFU-Cs) were counted at 7-10 days. For MMC experiments, MMC was added in dilution series of 0-20 nM. To determine the clonal growth of murine HSPCs, CAFC assay was performed by a limiting dilution analysis of bone marrow in micro-cultures using the bone marrow stromal cell line FBMD-1 (Parmar et al., 2010; Ploemacher et al., 1991). This assay quantifies a spectrum of hematopoietic cells that is well-validated to compare with other functional assays. Specifically, day 7 and day 14 CAFC correspond to early progenitor cells and to CFU-spleen day 12 cells, while the more primitive HSCs with long-term repopulating ability correspond to day 28 CAFC (Ploemacher et al., 1991).

Transplant assays

For Fancg-/- competitive transplant experiments, 3×105 to 5×105 Lin- bone marrow cells were purified on a column (Miltenyi), and transduced with sh Ctrl-Cherry and sh Trp53-GFP, cultured for 3 days, sorted by FACS, and an equal number of cells (1 to 1.5×105) were IV-injected in the tail of sub-lethally irradiated (4.5 Gy) syngenic mice. For parallel experiments, cells were transduced with sh Ctrl-GFP or sh Trp53-GFP.

For xenotransplant experiments, 3×105 to 5×105 human cord blood CD34+ cells were transduced overnight with sh FANCD2-GFP or tandem sh FANCD2-TP53-GFP, and 105 cells per mouse were IV-injected in the tail of sub-lethally irradiated (2.25 Gy) immunodeficient Nod/Scid/IL2-R γc null (NSG) mice. At day 5, transduction efficacy was measured by analyzing GFP+ cells in a sample of the cells grown in vitro; mice injected with > 50% GFP+ cells for both conditions were further analyzed. Human cells were quantified in the mouse blood by huCD45-PE antibody (Beckman Coulter) staining, and blood GFP+ cells were quantified. Nod/Scid/IL2-R γc null (NSG) mice (Jackson Laboratory) were housed in the pathogen-free animal facility of Institut Universitaire d'Hématologie, Paris. All experimental procedures were done in compliance with the French Ministry of Agriculture regulations for animal experimentation.

RNA extraction and CDKN1A/p21 expression in human cells

Dry cell pellets and frozen fetal tissues were extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA samples were reverse-transcribed and the cDNA was analyzed for CDKN1A/p21 and CDKN2A/p16 expression by quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using Taqman method (Applied Biosystems, primers Hs99999142_m1 for CDKN1A and Hs02902543_mH for CDKN2A). Gene expression values were normalized to expression of the reference genes GUS (Beta-glucuronidase) and ABL1 (Abelson gene) in accordance with international guidelines (Gabert et al., 2003; Bustin et al., 2009). Levels were indicated relative to the mean expression value of non-FA control samples which was arbitrary attributed to 1. Other values were expressed in fold change relative to this calibrator using the ΔCT method (log 2 scale).

Large-scale gene expression analysis

A FA EBV cell line that was transduced with sh Ctrl or sh p53 and treated with MMC was profiled at several time-points using large-scale gene expression analysis on the GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix). RNA extraction, labeling, and microarray hybridization were processed for all samples in the same set of experiments. Microarray data files are available on ArrayExpress (EBI) under accession number E-MTAB-1099. Supervised analysis of gene expression was performed with respect to differential expression between sh Ctrl and sh p53 at 72h after MMC treatment. A list of 294 probesets with false discovery rate < 0.05 (188 unique genes) was analyzed for biological pathways curated genesets using hypergeometrical test (www.broadinstitute.org). Heat maps were designed using dChip software and curated genesets (www.broadinstitute.org).

For bone marrow cell expression analysis in FA patients versus healthy donors, supervised analysis was performed from publicly available microarray data files (Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE16334) with respect to the absolute value of the differential expression between FA patients and healthy donors (N = 14 and N = 11, respectively; FA patients aged > 12 years were excluded to limit the possibility of somatic mosaicism or clonal evolution). Affymetrix GeneChip probeset summarization, background correction and quantile normalization were performed using the RMA routine as implemented in the “R” Affymetrix package. Probesets average expressions above 6 were kept resulting in 15171 probesets (10154 genes). 465 Gene Ontology genesets were scored using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis algorithm (GSEA, broadinstitute.org) and corresponding P values were computed using 2000 permutations. The heat-map of Figure 7 was designed using dChip software.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon test, student test, Chi–squared test for trend in proportions or the Odd ratio test as indicated in the legend of the figures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Bone marrow cells from FA patients display a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest signature

Inhibition of p53 or p21 in human FA CD34+ cells rescues CFU and xenotransplant assays

Hematopoietic stem cell defects in Fancd2-/- mice are rescued by loss of p53

p21 overexpression in FA during the constitution of the hematopoietic stem cell pool

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to William Vainchenker, Jean-Claude Gluckman and Hugues de Thé for helpful discussion. We thank Lucie Hernandez (Genomic facility, IUH), Niclas Setterblad (Plateau technique, IUH), Abigail Hamilton (DFCI) and Aurélie Coquin (APHP, Saint-Louis Hospital) for their technical assistance, Eric Benedetti (OHSU) for maintaining the Fancd2/p53 mouse colony, Daniela Geromin at the Cellulotheque of Saint-Louis Hospital, and Patrizia Vinciguerra (DFCI) for her initial observations on the role of p53 in cytokinesis failure of HSCs.

We thank the patients and their families, and the AFMF (Association Française de la Maladie de Fanconi) and FARF (Fanconi Anemia Research Fund) for their support to JS and ADD, respectively, and the physicians and nurses from French pediatric, genetic and/or haematological centers who have taken care of the patients. We also thank Joelle Roume, Laurence Loeuillet, Christine Francannet and Anne-Marie Beaufrere, who referred FA fetus samples to our laboratory.

Our center is supported by the French Government (Direction de l'Hospitalisation et de l'Organisation des Soins) as Centre de Référence Maladies Rares ‘Aplasies Médullaires Constitutionnelles’ (coordination G. Socié), and by the ‘Réseau INCa des Maladies Cassantes de l'ADN’ (coordination D. Stoppa-Lyonnet and A. Sarasin). This work was supported by a grant of the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) ‘Genopath’ to JS, and by grants of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) P01HL048546, RC4DK090913 and R01DK43889 to ADD, and NIH/NHLB P01HL048546-16 to MG. RC was supported by a fellowship of the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC) and by the Association Laurette Fugain.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NV, EG, TL, GS and JS: French Reference Center for Constitutional Bone Marrow Failure.

Conflict of interest statement: the authors have no disclosure.

REFERENCES

- Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GC, Meyers G. Bone marrow failure as a risk factor for clonal evolution: prospects for leukemia prevention. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007;2007:40–46. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroca V, Mouthon MA, Lewandowski D, Brunet de la Grange P, Gauthier LR, Pflumio F, Boussin FD, Arwert F, Riou L, Allemand I, et al. Impaired functionality and homing of Fancg-deficient hematopoietic stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellodi C, Kopmar N, Ruggero D. Deregulation of oncogene-induced senescence and p53 translational control in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. EMBO J. 2010;29:1865–1876. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns K, Hijmans EM, Mullenders J, Brummelkamp TR, Velds A, Heimerikx M, Kerkhoven RM, Madiredjo M, Nijkamp W, Weigelt B, et al. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Mohrin M, Sotiropoulou PA, Passegue E. DNA-damage response in tissue-specific and cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaldi R, Briot D, Larghero J, Vasquez N, Dubois d'Enghien C, Chamousset D, Noguera ME, Waisfisz Q, Hermine O, Pondarre C, et al. Spontaneous abrogation of the G2 DNA damage checkpoint has clinical benefits but promotes leukemogenesis in Fanconi anemia patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:184–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI43836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Palmai-Pallag T, Ying S, Hickson ID. Replication stress induces sister-chromatid bridging at fragile site loci in mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:753–760. doi: 10.1038/ncb1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Kennedy RD, Sidi S, Look AT, D'Andrea A. CHK1 inhibition as a strategy for targeting Fanconi Anemia (FA) DNA repair pathway deficient tumors. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, Yang Y, Dombkowski D, Sykes M, Scadden DT. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Artandi SE, Shen Q, Tam A, Lee SL, Gottlieb GJ, Greider CW, DePinho RA. p53 deficiency rescues the adverse effects of telomere loss and cooperates with telomere dysfunction to accelerate carcinogenesis. Cell. 1999;97:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Winter JP, Joenje H. The genetic and molecular basis of Fanconi anemia. Mutat Res. 2009;668:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans AJ, West SC. DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:467–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirac AM, Bernards R. Reversal of senescence in mouse fibroblasts through lentiviral suppression of p53. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11731–11734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokal I, Vulliamy T. Inherited aplastic anaemias/bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev. 2008;22:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour C, Corcione A, Svahn J, Haupt R, Poggi V, Beka'ssy AN, Scime R, Pistorio A, Pistoia V. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma are overexpressed in the bone marrow of Fanconi anemia patients and TNF-alpha suppresses erythropoiesis in vitro. Blood. 2003;102:2053–2059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour C, Svahn J. Fanconi anaemia: new strategies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(Suppl 2):S90–95. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freie B, Li X, Ciccone SL, Nawa K, Cooper S, Vogelweid C, Schantz L, Haneline LS, Orazi A, Broxmeyer HE, et al. Fanconi anemia type C and p53 cooperate in apoptosis and tumorigenesis. Blood. 2003;102:4146–4152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabert J, Beillard E, van der Velden VH, Bi W, Grimwade D, Pallisgaard N, Barbany G, Cazzaniga G, Cayuela JM, Cave H, et al. Standardization and quality control studies of ‘real-time’ quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia - a Europe Against Cancer program. Leukemia. 2003;17:2318–2357. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman E, Wagner JE. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood inherited bone marrow failure syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:127–132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothot A, Pyatt R, McMahel J, Rice S, Srour EF. Functional heterogeneity of human CD34(+) cells isolated in subcompartments of the G0 /G1 phase of the cell cycle. Blood. 1997;90:4384–4393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov AV, Komarova EA. Pathologies associated with the p53 response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001180. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling S, Granville L, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Olson S, Finegold M, Grompe M. Heterozygosity for p53 (Trp53+/-) accelerates epithelial tumor formation in fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (Fancd2) knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling S, Timmers C, Noll M, Finegold MJ, Jones SN, Meyn MS, Grompe M. Epithelial cancer in Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (Fancd2) knockout mice. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2021–2035. doi: 10.1101/gad.1103403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JG, Pereira-Smith OM. p53 is preferentially recruited to the promoters of growth arrest genes p21 and GADD45 during replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8356–8360. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Reinhardt HC, Bartkova J, Tommiska J, Blomqvist C, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J, Yaffe MB, Hemann MT. The combined status of ATM and p53 link tumor development with therapeutic response. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1895–1909. doi: 10.1101/gad.1815309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joenje H. Metabolism: alcohol, DNA and disease. Nature. 2011;475:45–46. doi: 10.1038/475045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y, D'Andrea AD. Expanded roles of the Fanconi anemia pathway in preserving genomic stability. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1680–1694. doi: 10.1101/gad.1955310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koomen M, Cheng NC, van de Vrugt HJ, Godthelp BC, van der Valk MA, Oostra AB, Zdzienicka MZ, Joenje H, Arwert F. Reduced fertility and hypersensitivity to mitomycin C characterize Fancg/Xrcc9 null mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:273–281. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruyt FA, Dijkmans LM, van den Berg TK, Joenje H. Fanconi anemia genes act to suppress a cross-linker-inducible p53-independent apoptosis pathway in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Blood. 1996;87:938–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer GM, D'Andrea AD. The effect of the Fanconi anemia polypeptide, FAC, upon p53 induction and G2 checkpoint regulation. Blood. 1996;88:1019–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutler DI, Singh B, Satagopan J, Batish SD, Berwick M, Giampietro PF, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR). Blood. 2003;101:1249–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin F, Crossan GP, Rosado IV, Arends MJ, Patel KJ. Fancd2 counteracts the toxic effects of naturally produced aldehydes in mice. Nature. 2011;475:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sejas DP, Zhang X, Qiu Y, Nattamai KJ, Rani R, Rathbun KR, Geiger H, Williams DA, Bagby GC, et al. TNF-alpha induces leukemic clonal evolution ex vivo in Fanconi anemia group C murine stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3283–3295. doi: 10.1172/JCI31772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Elf SE, Miyata Y, Sashida G, Huang G, Di Giandomenico S, Lee JM, Deblasio A, Menendez S, Antipin J, et al. p53 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milyavsky M, Gan OI, Trottier M, Komosa M, Tabach O, Notta F, Lechman E, Hermans KG, Eppert K, Konovalova Z, et al. A distinctive DNA damage response in human hematopoietic stem cells reveals an apoptosis-independent role for p53 in self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrin M, Bourke E, Alexander D, Warr MR, Barry-Holson K, Le Beau MM, Morrison CG, Passegue E. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error-prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan GL, D'Andrea AD. How the fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:223–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim V, Rosselli F. The FANC pathway and BLM collaborate during mitosis to prevent micro-nucleation and chromosome abnormalities. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:761–768. doi: 10.1038/ncb1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narla A, Ebert BL. Ribosomopathies: human disorders of ribosome dysfunction. Blood. 2010;115:3196–3205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-178129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveling K, Endt D, Hoehn H, Schindler D. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Fanconi anemia. Mutat Res. 2009;668:73–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ. DNA repair is crucial for maintaining hematopoietic stem cell function. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijnik A, Woodbine L, Marchetti C, Dawson S, Lambe T, Liu C, Rodrigues NP, Crockford TL, Cabuy E, Vindigni A, et al. DNA repair is limiting for haematopoietic stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2007;447:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nature05875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Q, Andreassen PR. Fanconi anemia proteins and endogenous stresses. Mutat Res. 2009;668:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar K, D'Andrea A, Niedernhofer LJ. Mouse models of Fanconi anemia. Mutat Res. 2009;668:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar K, Kim J, Sykes SM, Shimamura A, Stuckert P, Zhu K, Hamilton A, Deloach MK, Kutok JL, Akashi K, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell defects in mice with deficiency of Fancd2 or Usp1. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1186–1195. doi: 10.1002/stem.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploemacher RE, van der Sluijs JP, van Beurden CA, Baert MR, Chan PL. Use of limiting-dilution type long-term marrow cultures in frequency analysis of marrow-repopulating and spleen colony-forming hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse. Blood. 1991;78:2527–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quentin S, Cuccuini W, Ceccaldi R, Nibourel O, Pondarre C, Pages MP, Vasquez N, Dubois d'Enghien C, Larghero J, Peffault de Latour R, et al. Myelodysplasia and leukemia of Fanconi anemia are associated with a specific pattern of genomic abnormalities that includes cryptic RUNX1/AML1 lesions. Blood. 2011;117:e161–170. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-308726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani R, Li J, Pang Q. Differential p53 engagement in response to oxidative and oncogenic stresses in Fanconi anemia mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9693–9702. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PS, Socie G, Alter BP, Gluckman E. Risk of head and neck squamous cell cancer and death in patients with Fanconi anemia who did and did not receive transplants. Blood. 2005;105:67–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Seita J, Nussenzweig A, Hoeijmakers J, Weissman IL. Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature. 2007;447:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature05862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Jamieson CH, Weissman IL. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seita J, Rossi DJ, Weissman IL. Differential DNA damage response in stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyschab H, Sun Y, Friedl R, Schindler D, Hoehn H. G2 phase cell cycle disturbance as a manifestation of genetic cell damage. Hum Genet. 1993;92:61–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00216146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura A, Alter BP. Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev. 2010;24:101–122. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J. Fanconi anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:492–497. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J, Leblanc T, Larghero J, Dastot H, Shimamura A, Guardiola P, Esperou H, Ferry C, Jubert C, Feugeas JP, et al. Detection of somatic mosaicism and classification of Fanconi anemia patients by analysis of the FA/BRCA pathway. Blood. 2005;105:1329–1336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar J, Adair JE, Antoniou M, Bartholomae CC, Becker PS, Blazar BR, Bueren J, Carroll T, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Clapp DW, et al. Stem cell gene therapy for fanconi anemia: report from the 1st international Fanconi anemia gene therapy working group meeting. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1193–1198. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale A, De Franco F, Orleth A, Cambiaghi V, Giuliani V, Bossi D, Ronchini C, Ronzoni S, Muradore I, Monestiroli S, et al. Cell-cycle restriction limits DNA damage and maintains self-renewal of leukaemia stem cells. Nature. 2009;457:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature07618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra P, Godinho SA, Parmar K, Pellman D, D'Andrea AD. Cytokinesis failure occurs in Fanconi anemia pathway-deficient murine and human bone marrow hematopoietic cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3834–3842. doi: 10.1172/JCI43391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisfisz Q, Morgan NV, Savino M, de Winter JP, van Berkel CG, Hoatlin ME, Ianzano L, Gibson RA, Arwert F, Savoia A, et al. Spontaneous functional correction of homozygous fanconi anaemia alleles reveals novel mechanistic basis for reverse mosaicism. Nat Genet. 1999;22:379–383. doi: 10.1038/11956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NS. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in acquired aplastic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:72–77. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li J, Sejas DP, Pang Q. Hypoxia-reoxygenation induces premature senescence in FA bone marrow hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2005;106:75–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sejas DP, Qiu Y, Williams DA, Pang Q. Inflammatory ROS promote and cooperate with the Fanconi anemia mutation for hematopoietic senescence. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1572–1583. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.