Abstract

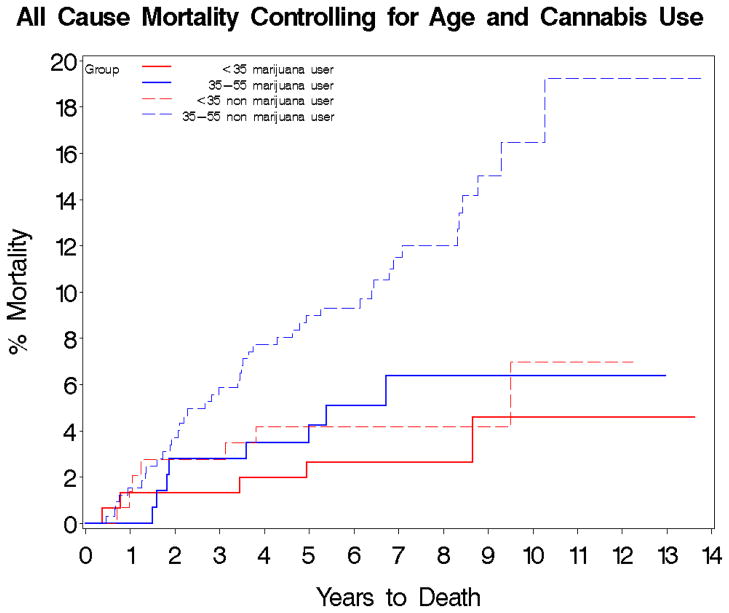

The impact of co-morbid substance use on mortality is not well studied in psychotic disorders. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of substance use on mortality in people with psychotic disorders and alcohol and/or drug use. We examined the rate of substance use and the risk of substance use on mortality risk over a 4–10 year period in 762 people with psychotic disorders. Deceased patients were identified from the Social Security Death Index and the Maryland Division of Vital Records. Substance use was defined as regular and heavy use or abuse or dependence. Seventy seven percent had co-morbid lifetime substance use, with co-morbid cannabis and alcohol use occurring most commonly. Out of 762 subjects, 62 died during follow up. In a Cox model, predicted mortality risk was higher in age group 35–55 compared to <35 years and in males, but reduced in cannabis users. Overall five- (3.1% vs 7.5%) and ten-year mortality risk (5.5% vs. 13.6%) was lower in cannabis users than in non-users with psychotic disorders (p=0.005) in a survival model. Alcohol use was not predictive of mortality. We observed a lower mortality risk in cannabis-using psychotic disorder patients compared to cannabis non-users despite subjects having similar symptoms and treatments. Future research is warranted to replicate these findings and to shed light on the anti-inflammatory properties of the endocannabinoid system and its role in decreased mortality in people with psychotic disorders.

Keywords: psychotic disorders, substance use, cannabis, alcohol, mortality

Background

Over the course of their lifetime, approximately half of all people with schizophrenia will have a co-occurring substance use disorder [SUD] (Havassy et al., 2004). According to the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study and the National Comorbidity Survey, these rates are significantly higher in people with severe mental illness such as schizophrenia than in the general population (Kessler et al., 1994; Regier et al., 1990). Alcohol, cannabis, and to a lesser extent, cocaine and amphetamine are the most frequently abused substances in people with schizophrenia, with regional variation on use patterns (Cantor-Graae et al., 2001; Drake et al., 1996; Mueser et al., 1990; Siris et al., 1988). The reported rates of alcohol use is 20% to 60%, cannabis use from 12% to 42%, cocaine use from 15% to 50% (Chambers et al., 2001) and amphetamine use from 10% to 25% (Littrell et al., 2001; Mueser et al., 1990; Siris et al., 1988) in people with schizophrenia. The use of more than two drugs at the same time is also common (Soyka et al., 1993). Other drugs of abuse in this population include heroin, and hallucinogens; however, these are less often the drugs of choice (Margolese et al., 2004). A United Kingdom study reported that rates of co-occurring schizophrenia and substance abuse are increasing by about 10% per year, and afflicted co-morbid individuals’ average age decreasing from 38 years to 34 years during 1993 to 1998 (Frisher et al., 2004).

It is known that some types of substance use are associated with health co-morbidities. On average, people with alcohol or drug use have approximately 30% more physical diagnoses per case than non-substance users (Adrian & Barry, 2003). Morbidities and mortalities from alcohol and drug use include Hepatitis B and C, other liver diseases, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and other infectious diseases, overdose and poisoning, trauma, suicide and accidents (Brugal et al., 2004; Copeland et al., 2004; Demetriades et al., 2004; Suominen et al., 2004). The odds ratios for having diabetes, heart disease, asthma, skin infections, cancer, respiratory disorders and gastrointestinal disorders were higher in patients with co-occurring substance abuse compared to patients with severe mental illness and no substance abuse diagnosis (Dickey et al., 2002). Other serious consequences of substance use include victimization, trauma, accidents (Brugal et al., 2004; Copeland et al., 2004; Demetriades et al., 2004; Goodman et al., 2001; Suominen et al., 2004), and homelessness (Dixon, 1999).

Some evidence suggests that co-occurring somatic disorders are higher in the dually diagnosed population and that premature death may be more likely (Beijer et al., 2007; Dickey et al., 2004; Dickey et al., 2002; Maynard et al., 2004). However, the impact of alcohol and illicit drug use, particularly cannabis, which is widely used, on mortality risk remains unknown in the psychotic disorders (PD) population. This is critical to determine because the average life expectancy in schizophrenia is already about 20–25 years shorter than the general population (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Harris & Barraclough, 1998; Newman & Bland, 1991). The objective of this study was to examine the impact of substance use on mortality in a large cohort of people with PD and alcohol and/or drug use.

Methods

Study population

A total of 4,434 unique patient records were identified from a State of Maryland database from seven inpatient mental health facilities between 1994 and 2000. Of 4,434 subjects, 1,222 met the criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS) and were 18 to 55 years of age. Of the 1,222, 762 had clinical charts with race and drug use information available. Drug use information was collected from charts using an algorithm and specific intake forms detailing drug use histories.

Identification of deceased people

Deceased patients were identified through matching patient records with the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) either by their social security numbers or by their names with confirmed date of birth. The SSDI is a national computerized database that records death dates and locations that have been reported to the organization. Records were extracted from SSDI from 1994 through December 31, 2004; patients were thus potentially followed for mortality for between four and 10 years after their index admission. In addition, the death certificates were collected from the Maryland Division of Vital Records to determine the immediate cause and contributing causes of death. Death certificates were available for all decedents in this study.

Clinical Data Collection

Clinical data collection was done between 2003 and 2007 for all the 4,434 subjects who were treated in State of Maryland inpatient facilities. Medical records were reviewed to verify DSM diagnoses, co-morbid diseases, smoking status, family history of medical disorders, and severity of illness as well as to collect data on health indices such as height, weight, lipids, glucose and blood pressures. In addition, substance use data was collected using a standardized approach that included data retrieval from DSM diagnoses, urine toxicology data, substance use intake forms and nursing admission notes. All data was collected in the same way. Substance users were defined as subjects with frequent or regular use (more than occasional use), having substance abuse or dependence. Occasional, light and infrequent use were not included, as we wanted to determine the impact of significant drug use on mortality. The following substances identified by name or corresponding street name: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens (Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin/mushrooms and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA), phencyclidine (PCP), amphetamines and inhalants. Smokers were defined as subjects who ever smoked. Smokers were further categorized as subjects who smoked more than 1 pack daily, less than 1 pack daily or unknown amount.

Final sample

A sample of 762 subjects had data available on lifetime history of substance use and race. In order to calculate risk by gender and race, the small number with a race other than Caucasian or African American were excluded. Only those between the ages of 18 and 55 years were included. This final sample included Caucasian or African American subjects, aged 18–55 at start of follow-up, with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis NOS, and who were on second generation antipsychotics at the index admission and for whom complete data on substance use and cigarette smoking were available (N=762).

The University of Maryland and Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Institutional Review Boards approved this study, and an exemption from informed consent was granted for use of administrative health records.

Statistical Analyses

This study specifically examined the impact of lifetime history of substance use on all cause mortality in people with PD. Comparison between drug users and non-drug users were conducted by using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess the distribution of time to all cause mortality in alcohol and cannabis users and non-users; log rank tests were used for unadjusted comparisons of mortality. These survival analyses were stratified by age in order to take account of the differences in the mortality among different age groups (<35 years, 35–55 years). We chose 35 years to separate the two groups because people less than 35 years are unlikely to die from cardiac related diseases. Furthermore, in a paper published on cigarette smoking and mortality using the same sample (Kelly et al., 2011), we separated age groups as <35 years and 35–54 years. Cox regression models were used to examine the association of mortality with the most common substances used (cannabis and alcohol) after adjusting for age (18–35 years and 35–55 years), gender, race and smoking status. Previous results from our group found no effects of antipsychotics treatment including clozapine on mortality in this population (Kelly et al., 2010) Interactions between cannabis and alcohol use, and between age and alcohol or cannabis use were examined. All tests were two-sided with alpha=0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 762 patients (schizophrenia N=402, schizoaffective disorder N=274, psychosis NOS N=86) were included in this study. The majority of the subjects were Caucasian (58%) and 61% were smokers. Substance use was found to be prevalent in the sample with 584/762 (77%) having co-morbid lifetime use. Cannabis and alcohol use were the most commonly reported substances with 478/762 (63%) using alcohol and 295/762 (39%) using cannabis. Other substances of abuse along with demographic information are reported in Table 1. There was no significant difference in Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score between cannabis users 37.8 (10.4) and non-users 38.1 (11.0) p=0.76 and alcohol users 38.2 (10.5) and non-users (37.6 (11.1) p=0.49. Antipsychotics prescribed at the index visit were similar in users and non-users of cannabis or alcohol (data not shown).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Variables (N=762)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.3 (8.8)* |

| Gender | |

| Males | 534(70.1) |

| Females | 228 (29.9) |

| Race | |

| Caucasians | 443 (58.1) |

| African Americans | 319 (41.9) |

| Age group | |

| <35 years | 296 (38.8) |

| ≥ 5–55 years | 466 (61.2) |

| Non-Smokers | 290 (38.6) |

| Smokers | 461 (61.4) |

| <1 pack daily | 130 (28.2) |

| ≥ 1 pack daily | 218 (47.3) |

| Unknown amount | 113 (24.5) |

| Schizophrenia | 402 (52.8) |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 274 (35.9) |

| Psychosis NOS | 86 (11.3) |

| No clozapine use | 490 (64.3) |

| Ever on clozapine | 272 (35.7) |

| Alcohol users | 478 (62.7) |

| Cannabis users | 295 (38.7) |

| Cocaine users | 238 (31.2) |

| Heroin users | 95 (12.5) |

| Hallucinogen users | 83(10.9) |

| PCP users | 69 (9.1) |

| Amphetamine users | 22 (2.9) |

| Inhalants users | 13 (1.7) |

| Substance use | 584 (77) |

| Global Assessment of Functioning score | 38.0 (10.7)* |

mean (SD)

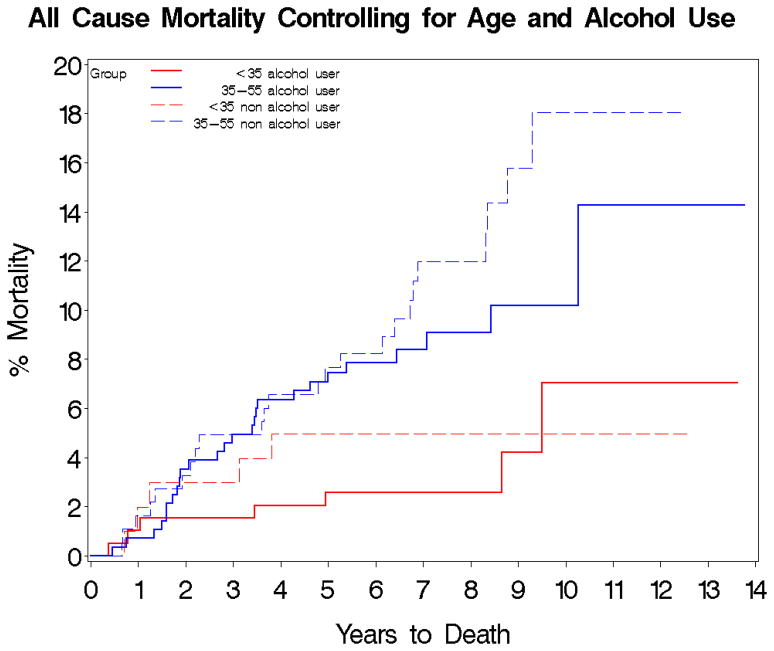

Mortality Risk

Overall of the 762 subjects, 62 died during follow-up. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall 5- and 10-year mortality risks were 5.8% and 10.6%, respectively. Ten-year mortality risk in patients 35–55 years old at baseline was more than double (13.8%) the 10-year risk in patients under 35 years old at baseline (6.0%) (χ2=11.1, df=1, p=0.0009). In the survival analysis, cannabis users had a lower 5- (3.1%) and 10-year (5.5%) mortality risk than cannabis non-users 5- (7.5%) and 10-year (13.6%) (χ2=8.0, df=1, p=0.005). Similarly, alcohol users had a lower 5- and 10-year mortality risk than alcohol non-users (5-year, 5.5% vs. 6.7%; 10-year, 8.9% vs. 13.1%); however, the differences were not significant (χ2=1.8, df=1, p=0.18). After stratifying by age <35 years versus age 35–55 years, these trends toward reduced mortality in alcohol or cannabis users, compared to non-users remained the same. After excluding cannabis or alcohol users, there were only 11 deaths in subjects using all of the other illicit drug groups listed; therefore, these substances were not included in the subsequent survival analysis. No significant differences in cause specific mortality by alcohol or substance use was detected.

Risk Factors for Mortality

In a Cox proportional hazards model (Table 2), the contributions of age, gender, smoking status, lifetime history of cannabis use and lifetime history of alcohol use were examined. Mortality risk was significantly increased in males (Hazard Ratio (HR)=2.2, p=0.02), older ages (35–55 years versus <35 years) (HR=2.3, p=0.01), but decreased in cannabis users (HR=0.5, p=0.04). Alcohol was not predictive of mortality in the cox model (HR=0.8, p=0.29). There were no significant interactions between cannabis and alcohol use (χ2=0.3, df=1, p=0.61), or between use of either substance and age.

Table 2.

All-Cause Mortality using Additive Cox Model for Alcohol and Cannabis Use adjusted for age, gender and smoking status

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | χ2, df, p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | 5.6, 1, 0.02 |

| 35–55 years | 2.3 (1.2–4.3) | 6.2, 1, 0.01 |

| White | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 1.0, 1, 0.32 |

| Alcohol | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 1.1, 1, 0.29 |

| Cannabis | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 4.1, 1, 0.04 |

| Smoking | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) | 1.9, 1, 0.17 |

Interaction between alcohol use and age group: χ2=0.004, df=1, p=0.95

Interaction between cannabis use and age group: χ2=0.2, df=1, p=0.64

Interaction between alcohol and cannabis use: χ2=0.3, df=1, p=0.61

Table 3 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in Cannabis Users versus Cannabis Non-users.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics in Cannabis Users versus Cannabis Non-users

| Cannabis users N=295 (38.7%) N (%) |

Cannabis non-users N=467 (61.3%) N (%) |

Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age* | 34.2 (8.6) | 39.2 (8.4) | t=8.1, df=760, p<0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Gender | χ2=13.1, df=1, p=0.0003 | ||

| Males | 229 (77.6) | 305 (65.3) | |

| Females | 66 (22.4) | 162 (34.7) | |

|

| |||

| Race | χ2=5.5, df=1, p= 0.02 | ||

| Caucasians | 156 (52.9) | 287 (61.5) | |

| African Americans | 139 (47.1) | 180 (38.5) | |

|

| |||

| Age group | χ2=32.6, df=1, p= <0.0001 | ||

| <35 years | 152 (51.5) | 144 (30.8) | |

| 35–55 years | 143 (48.5) | 323 (69.2) | |

|

| |||

| Mortality | 13 (4.4) | 49 (10.5) | χ2=9.0, df=1, p= 0.003 |

| No Mortality | 282 (95.6) | 418 (89.5) | |

|

| |||

| Smokers | 193 (65.6) | 268 (58.6) | χ2=3.7, df=1, p=0.05 |

| Non-Smokers | 101 (34.4) | 189 (41.4) | |

|

| |||

| No clozapine | 183 (62.0) | 307 (65.7) | χ2=1.1, df=1, p=0.3 |

| Ever on clozapine | 112 (38.0) | 160 (34.3) | |

|

| |||

| Alcohol users | 242 (82.0) | 236 (50.5) | χ2=76.7, df=1, p= <0.0001 |

| Alcohol non-users | 53 (18.0) | 231 (49.5) | |

|

| |||

| Schizophrenia | 148 (50.2) | 254 (54.4) | χ2=15.6, df=2, p=0.0004 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 97 (32.9) | 177 (37.9) | |

| Psychosis NOS | 50 (16.9) | 36 (7.7) | |

|

| |||

| Follow up, years* | 7.4 (2.1) | 7.4 (2.3) | t=−0.0, df=760, p=1.0 |

|

| |||

| Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)* | 37.8 (10.4) | 38.1 (11.0) | t=0.3, df=636, p=0.76 |

| Causes of death | χ2=6.9, df=7, p=0.4 | ||

| Cardiac | 4 (30.8) | 13 (26.5) | |

| Cerebrovascular | 0 (0.0) | 4 (8.2) | |

| Cancer | 0 (0.0) | 4 (8.2) | |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 (7.7) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Non-HIV Infections | 2 (15.4) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Diabetes | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Respiratory | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Other | 5 (38.5) | 18 (36.7) | |

| Suicide | 2 (40) | 1 (5.6) | |

| End stage diabetic renal disease | 1 (20) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Alcohol, Narcotic, Clozapine intoxication | 2 (40) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Seizure disorder | 3 (16.7) | ||

| Acute Thermal Injury of Airway and Smoke Inhalation | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Bowel obstruction | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Anoxic encephalopathy, encephalopathy | 3 (16.7) | ||

| Hypoxemia | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Myeloproliferative disorder | 1 (5.6) | ||

mean (SD)

Discussion

Summary of results

Seventy seven percent of the patients in this study reported a lifetime history of substance or alcohol use. The two most commonly used substances were alcohol and cannabis. After controlling for age, sex, smoking status and alcohol use in the cox model, we observed a lower mortality risk adjusted variable in cannabis-users compared to cannabis non-users despite subjects having similar symptoms and antipsychotic treatment. It is surprising that the GAF in lifetime users and non-users of cannabis or alcohol users was not significantly different. This may be due to the fact that GAF is a subjective measurement and it was only a one time cross-sectional assessment. Although not significant in the Cox model, when stratified into four groups, those using alcohol in the older age group had significantly higher mortality in the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. This finding may be driven by the age factor.

We did not include people over 55 years because significant medical co-morbidity may confound the mortality finding. Further, in schizophrenia the average life expectancy is 51–61 years (Newman & Bland 1991; Harris & Barraclough 1998; Colton & Manderscheid, 2006). Finally, the prevalence of substance use in age group >55 years was much less compared to age groups <35 years and 35–55 years.

Comparison with other similar studies

Health consequences and increased mortality with cannabis in the general population are not widely reported and remain controversial particularly regarding cancer and cardiovascular effects (Aryana & Williams, 2007; Hashibe et al., 2005; Kapp, 2003). Swedish soldiers (N=45,540) who were high consumers of cannabis, which was defined as use on more than 50 occasions, were followed for 15 years. After controlling for social background variables in a multivariate model, no excess mortality was found (Andreasson & Allebeck, 1990). In 65,171 Kaiser Permanente acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) database medical care program enrollees aged 15 through 49 years, current cannabis use was not associated with a significantly increased risk of non-AIDS mortality in men and of total mortality in women (Sidney et al., 1997). Cannabis use was associated with a decreased risk of premature death (odds ratio=0.83, p=0.02) in 561 substance abusers in Sweden admitted to a detoxification unit from 1970 through 1978 and who were followed until 2006. Chronic alcohol users had increased risk of non-drug related death. This study had patients with schizophrenia, substance induced psychosis, affective disorders, neurosis, anxiety, hysteria, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive neurosis (Nyhlen et al., 2011). Our sample included only people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis NOS.

Consistent with our findings, in another study with 83 inpatients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorder with alcohol and drug abuse or dependence, global functioning in the substance use group was not worse than substance non-users (Dixon et al., 1991). Some evidence suggests that cannabis users may have higher functioning and paradoxically better outcomes, given the growing body of evidence on the endocannabinoid system in PD as well as some literature on the beneficial effects of cannabis. People with schizophrenia and cannabis use tend to have better cognitive function than non-substance users (D’Souza et al., 2005), which in part, explains better functioning. In a recently published study of 99 people with first psychotic episode, cannabis users had better cognition and social function at psychosis onset (Leeson et al., 2011). Cannabis users having better cognition may be due to the neuroprotective effect on the developing brain before the first psychotic episode. There is evidence from animal models that cannabis upregulates neurotrophins and enhances prefrontal neurotransmitter release (Jockers-Scherubl et al., 2007; Loberg & Hugdahl, 2009). Finally, continuous cannabis use after psychosis onset has been associated with a reduction in dysphoria and increased sociability (Dekker et al., 2009).

It is estimated that far fewer people with schizophrenia are considered regular alcohol abusers (<20%) compared to lifetime alcohol use rates reported to be as high as 77% (Cruce & Ojehagen, 2007; Drake et al., 1989; Duke et al., 1994; Fowler et al., 1998; McCreadie, 2002) and it may reflect social use more than dependence (Fowler et al., 1998). This discrepancy between frequency of lifetime use and regular use of alcohol in people with schizophrenia might account for why the observed trend toward mortality reduction in alcohol users in our population is not statistically significant. In the general population moderate alcohol intake has been frequently reported to be associated with decreased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Agarwal, 2002; Gronbaek et al., 2004; Klatsky et al., 2003; Malinski et al., 2004; Mukamal et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2002; Wells et al., 2004; Wilkins, 2002).

In contrast to our study, in 71,225 Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries, Medicaid beneficiaries with dual diagnoses had more (odds ratio 6–8) deaths than those with only a psychiatric disorder. This study, however, lacked comprehensive data on diagnoses and did not control for treatment environment. The authors explained this by the disproportionate number of deaths that were injury deaths, homicide, suicide, and accidents (Dickey et al., 2004). Our study did not have details on injury deaths, homicide, suicide, and accidents. After adjusting for age, 2416 individuals discharged from Washington State mental hospitals with mental illness and SUD had a 44% higher risk of death than individuals with mental illness and SUD only (Maynard et al., 2004). These two studies did not assess medical sequelae of substance use. The risk-adjusted probability of mortality over a 7-year period among 169,051 male veterans with or without co-occurring SUD was 55% higher among veterans with dual diagnosis than among those without SUDs (Rosen et al., 2008). This study controlled for preexisting medical conditions in contrast to the two studies mentioned above (Dickey et al., 2004; Maynard et al., 2004). Only our study analyzed the mortality risk separately for alcohol and cannabis in PD where the endocannabinoid system may play a different role in risk of disease and pathobiology.

How is cannabis use associated with decreased mortality?

There are multiple explanations for decreased mortality with cannabis use; however, this remains unknown. First, it is possible that cannabis users may have higher functioning and in return may have lower mortality. We did not find differences however in GAF scores, however this may not adequately proxy symptomatology and functioning. Also, cannabis itself may have some health benefits. The psychoactive component of cannabis, d9-tetrahydrocannabinol, is well tolerated and already in clinical use for nausea associated with cancer chemotherapy and appetite stimulation with the AIDS wasting syndrome. In the cannabis users group there were no deaths from cancer during the follow up period while there were four cancer deaths in the cannabis non-users group. Activation of microglial CB1 has been shown to inhibit the release of nitric oxide, suggesting that CB1 may be anti-inflammatory (Waksman et al., 1999). In addition, the endocannabinoid system has been shown to attenuate inflammatory events such as the differentiation of myelin-specific T cells, the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, nitric oxide (NO), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2 and IL-6 and the activation and infiltration of microglia, leading to a slowed progression of inflammatory disorders (Croxford & Miller, 2003; Ortega-Gutierrez et al., 2005). CB1 activation has been shown to be effective in limiting cell death following excitotoxic lesions, while CB2 receptor is involved in decreasing inflammatory immune cell response to disease (Scotter et al., 2010). AM404, an endocannabinoid modulator, normalizes chronic constriction injury in NO activity (Costa et al., 2006; La Rana et al., 2006), cyclooxygenase-2 activity (La Rana et al., 2006), cytokine levels such as TNF-α, NF-κB levels and IL-10 (Costa et al., 2006). In the USA, since 1996, 14 states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington) have amended their state laws to allow cannabis, prescribed by licensed physicians, to be used, by people with debilitating medical conditions (Hoffmann & Weber, 2010; MacDonald, 2009). Finally, the National Institutes of Health, the Institute of Medicine and the American College of Physicians have renewed their interest in medical marijuana for research and development.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the large sample size (N=762) for which medical records including histories of substance use were available. However, the number who died during the period is somewhat small. Further, evidence to date examining mortality in people who use alcohol and illicit substances is limited by small samples (Beijer et al., 2007), and administrative claims data (Maynard et al., 2004), and unclear or combined diagnoses (Dickey et al., 2004; Maynard et al., 2004). Previous studies have found that over 25% of medical record diagnoses do not match administrative data (Staffa et al., 1995). This type of clinical data has many strengths over using administrative or Medicaid data by not being tied to claims. Another strength of this study is the follow-up period of 4–10 years, as well as looking only at those patients under the age of 55. By doing this, we did not include the large increases in significant medical co-morbidity in the oldest ages that may obscure effects of drug abuse over the lifetime.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective data gathering on substance use. Further, we included subjects with regular to heavy substance use, but not necessarily having an Axis I diagnosis of abuse or dependence. We carefully scoured the medical records, as this was the primary study aim; however, we do not have specific use patterns including frequency, amount and duration. Subjects were identified by having an inpatient hospitalization in state facilities, thus representing a group who likely received medical assistance, had more severe mental illness at the start of mortality follow-up, were less likely to be dependent or regular abusers of substances at the start of follow-up, and who may have been more or less likely to receive adequate medical treatment. Given the inclusion criteria, these subjects identified through inpatient hospitalization records may not be representative of patients treated entirely in the outpatient sector. Also, the average life expectancy of the general population in the USA is 76 years and we analyzed only people until 55 years. But in schizophrenia the average life expectancy is 51–61 years (Newman & Bland 1991; Harris & Barraclough 1998; Colton & Manderscheid, 2006). Finally, there is accumulating evidence that cannabis use, particularly in those genetically at risk (Caspi et al., 2005), may be associated with an increased risk of schizophreniform disorder. We did not examine genetic effects and risk, nor did we examine the age of onset of illness and relate this to the onset of cannabis use. Thus, we cannot comment on the relationship of cannabis to schizophrenia per se in this study.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine the risk of mortality with cannabis and alcohol in people with PD. This interesting finding of decreased mortality risk, specifically in cannabis users, is a novel finding and one that will need replication in larger epidemiological studies. Future research is needed to shed light on the mechanisms of cannabis and its role in decreased mortality in people with PD. There is a growing need to understand the long-term effects of cannabis especially because medical marijuana is legal in many states in USA for chronic debilitating medical conditions. Better understanding the risk of mortality in people who are dually diagnosed will enable the field to better target interventions.

Figure 1.

Time to death in alcohol users vs. alcohol non-users by age group. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Cumulative Probability of All-Cause Death by Years of Follow-up, Age and Alcohol use.

Log-rank test: χ2=12.7, df=3, p=0.005

<35 years alcohol user N=195

35–55 years alcohol user N=283

<35 years alcohol non-user N=101

35–55 years alcohol non-user N=183

Figure 2.

Time to death in cannabis users vs. cannabis non-users by age group. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Cumulative Probability of All-Cause Death by Years of Follow-up, Age and Cannabis use.

Log-rank test: χ2=17.5, df=3, p=0.0006

<35 years cannabis user N=152

35–55 years cannabis user N=143

<35 years cannabis non-user N=144

35–55 years cannabis non-user N=323

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adrian M, Barry SJ. Physical and mental health problems associated with the use of alcohol and drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:1575–1614. doi: 10.1081/ja-120024230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal DP. Cardioprotective effects of light-moderate consumption of alcohol: a review of putative mechanisms. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:409–415. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson S, Allebeck P. Cannabis and mortality among young men: a longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Scand J Soc Med. 1990;18:9–15. doi: 10.1177/140349489001800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryana A, Williams MA. Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: speculation or scientific certainty? Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beijer U, Andreasson A, Agren G, Fugelstad A. Mortality, mental disorders and addiction: a 5-year follow-up of 82 homeless men in Stockholm. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:363–368. doi: 10.1080/08039480701644637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugal MT, Barrio G, Royuela L, Bravo MJ, de la Fuente L, Regidor E. [Estimating mortality attributed to illegal drug use in Spain] Med Clin (Barc) 2004;123:775–777. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae E, Nordstrom LG, McNeil TF. Substance abuse in schizophrenia: a review of the literature and a study of correlates in Sweden. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J, Murray R, Harrington H, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Williams B, Braithwaite A, Poulton R, Craig IW. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57 (10):1117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Krystal JH, Self DW. A neurobiological basis for substance abuse comorbidity in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland L, Budd J, Robertson JR, Elton RA. Changing patterns in causes of death in a cohort of injecting drug users, 1980–2001. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1214–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa B, Siniscalco D, Trovato AE, Comelli F, Sotgiu ML, Colleoni M, Maione S, Rossi F, Giagnoni G. AM404, an inhibitor of anandamide uptake, prevents pain behaviour and modulates cytokine and apoptotic pathways in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:1022–1032. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford JL, Miller SD. Immunoregulation of a viral model of multiple sclerosis using the synthetic cannabinoid R+WIN55,212. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1231–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI17652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruce G, Ojehagen A. Risky use of alcohol, drugs and cigarettes in a psychosis unit: a 1 1/2 year follow-up of stability and changes after initial screening. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G, Gueorguieva R, Cooper TB, Krystal JH. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker N, Linszen DH, De Haan L. Reasons for cannabis use and effects of cannabis use as reported by patients with psychotic disorders. Psychopathology. 2009;42:350–360. doi: 10.1159/000236906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades D, Gkiokas G, Velmahos GC, Brown C, Murray J, Noguchi T. Alcohol and illicit drugs in traumatic deaths: prevalence and association with type and severity of injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Dembling B, Azeni H, Normand SL. Externally caused deaths for adults with substance use and mental disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02287340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Normand SL, Weiss RD, Drake RE, Azeni H. Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:861–867. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35 (Suppl):S93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Haas G, Weiden PJ, Sweeney J, Frances AJ. Drug abuse in schizophrenic patients: clinical correlates and reasons for use. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:224–230. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA. Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia. A prospective community study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:408–414. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT. Assessing substance use disorder in persons with severe mental illness. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 1996:3–17. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319960203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke PJ, Pantelis C, Barnes TR. South Westminster schizophrenia survey. Alcohol use and its relationship to symptoms, tardive dyskinesia and illness onset. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:630–636. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, Lewin TJ. Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:443–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisher M, Collins J, Millson D, Crome I, Croft P. Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric illness and substance misuse in primary care in England and Wales. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:1036–1041. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.017384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Swartz M, Essock SM, Osher FC, Butterfield MI, Swanson J. Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: prevalence and correlates. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14:615–632. doi: 10.1023/A:1013026318450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronbaek M, Johansen D, Becker U, Hein HO, Schnohr P, Jensen G, Vestbo J, Sorensen TI. Changes in alcohol intake and mortality: a longitudinal population-based study. Epidemiology. 2004;15:222–228. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000112219.01955.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, Morgenstern H, Greenland S, Zhang ZF. Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Alvidrez J, Owen KK. Comparisons of patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders: implications for treatment and service delivery. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:139–145. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann DE, Weber E. Medical marijuana and the law. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1453–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockers-Scherubl MC, Wolf T, Radzei N, Schlattmann P, Rentzsch J, Gomez-Carrillo de Castro A, Kuhl KP. Cannabis induces different cognitive changes in schizophrenic patients and in healthy controls. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1054–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp C. Swiss debate whether to legalise cannabis. Alcohol and tobacco pose far greater danger, say advocates of cannabis legalisation. Lancet. 2003;362:970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DL, McMahon RP, Liu F, Love RC, Wehring HJ, Shim JC, Warren KR, Conley RR. Cardiovascular disease mortality in patients with chronic schizophrenia treated with clozapine: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:304–311. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04718yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DL, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, Liu F, Mackowick KM, Boggs DL, Warren KR, Feldman S, Shim JC, Love RC, Dixon L. Cigarette smoking and mortality risk in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37 (4):832–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatsky AL, Friedman GD, Armstrong MA, Kipp H. Wine, liquor, beer, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:585–595. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rana G, Russo R, Campolongo P, Bortolato M, Mangieri RA, Cuomo V, Iacono A, Raso GM, Meli R, Piomelli D, Calignano A. Modulation of neuropathic and inflammatory pain by the endocannabinoid transport inhibitor AM404 [N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-eicosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenamide] J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1365–1371. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson VC, Harrison I, Ron MA, Barnes TR, Joyce EM. The Effect of Cannabis Use and Cognitive Reserve on Age at Onset and Psychosis Outcomes in First-Episode Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell KH, Petty RG, Hilligoss NM, Peabody CD, Johnson CG. Olanzapine treatment for patients with schizophrenia and substance abuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loberg EM, Hugdahl K. Cannabis use and cognition in schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2009;3:53. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.053.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. Medical marijuana: informational resources for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinski MK, Sesso HD, Lopez-Jimenez F, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease mortality in hypertensive men. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:623–628. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolese HC, Malchy L, Negrete JC, Tempier R, Gill K. Drug and alcohol use among patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses: levels and consequences. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:157–166. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C, Cox GB, Hall J, Krupski A, Stark KD. Substance use and five-year survival in Washington State mental hospitals. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2004;31:339–345. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000028896.44429.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreadie RG. Use of drugs, alcohol and tobacco by people with schizophrenia: case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:321–325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, Singh H, Bellack AS, Kee K, Morrison RL, Yadalam KG. Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:31–56. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA, Camargo CA, Jr, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Roles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:109–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RP, Connett JE, Tyas SL, Bond R, Ekuma O, Silversides CK, Barnes GE. Alcohol volume, drinking pattern, and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: is there a U-shaped function? Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:242–248. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36:239–245. doi: 10.1177/070674379103600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyhlen A, Fridell M, Backstrom M, Hesse M, Krantz P. Substance abuse and psychiatric co-morbidity as predictors of premature mortality in Swedish drug abusers: a prospective longitudinal study 1970–2006. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Gutierrez S, Molina-Holgado E, Arevalo-Martin A, Correa F, Viso A, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, Di Marzo V, Guaza C. Activation of the endocannabinoid system as therapeutic approach in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. FASEB J. 2005;19:1338–1340. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2464fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Kuhn E, Greenbaum MA, Drescher KD. Substance abuse-related mortality among middle-aged male VA psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:290–296. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotter EL, Abood ME, Glass M. The endocannabinoid system as a target for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:480–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney S, Beck JE, Tekawa IS, Quesenberry CP, Friedman GD. Marijuana use and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:585–590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris SG, Kane JM, Frechen K, Sellew AP, Mandeli J, Fasano-Dube B. Histories of substance abuse in patients with postpsychotic depressions. Compr Psychiatry. 1988;29:550–557. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(88)90074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Albus M, Kathmann N, Finelli A, Hofstetter S, Holzbach R, Immler B, Sand P. Prevalence of alcohol and drug abuse in schizophrenic inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;242:362–372. doi: 10.1007/BF02190250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staffa JA, Jones JK, Gable CB, Verspeelt JP, Amery WK. Risk of selected serious cardiac events among new users of antihistamines. Clin Ther. 1995;17:1062–1077. doi: 10.1016/0149-2918(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suominen K, Isometsa E, Haukka J, Lonnqvist J. Substance use and male gender as risk factors for deaths and suicide--a 5-year follow-up study after deliberate self-harm. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:720–724. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0796-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman Y, Olson JM, Carlisle SJ, Cabral GA. The central cannabinoid receptor (CB1) mediates inhibition of nitric oxide production by rat microglial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:1357–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Broad J, Jackson R. Alcohol consumption and its contribution to the burden of coronary heart disease in middle-aged and older New Zealanders: a population-based case-control study. N Z Med J. 2004;117:U793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins K. Moderate alcohol consumption and heart disease. Health Rep. 2002;14:9–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]