Abstract

Background

The Step Study found that men who had sex with men (MSM) who received an adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) vector-based vaccine and were uncircumcised or had prior Ad5 immunity had a higher HIV incidence than MSM who received placebo. We investigated whether differences in HIV exposure, measured by reported sexual risk behaviors, may explain the increased risk.

Methods

Among 1,764 MSM in the trial, 724 were uncircumcised, 994 had prior Ad5 immunity and 560 were both uncircumcised and had prior Ad5 immunity. Analyses compared sexual risk behaviors and perceived treatment assignment among vaccine and placebo recipients, determined risk factors for HIV acquisition and examined the role of insertive anal intercourse in HIV risk among uncircumcised men.

Findings

Few sexual risk behaviors were significantly higher in vaccine vs. placebo recipients at baseline or during follow-up. Among uncircumcised men, vaccine recipients at baseline were more likely to report unprotected insertive anal intercourse with HIV negative partners (25.0% vs. 18.1%; p=0.03). Among uncircumcised men who had prior Ad5 immunity, vaccine recipients were more likely to report unprotected insertive anal intercourse with partners of unknown HIV status (46.0% vs. 37.5%; p=0.05). Vaccine recipients remained at higher risk of HIV infection compared to placebo recipients (HR =2.8; 95% CI:1.7, 6.8) controlling for potential confounders.

Interpretation

These analyses do not support a behavioral explanation for the increased HIV infection rates observed among uncircumcised men in the Step Study. Identifying biologic mechanisms to explain the increased risk is a priority.

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00095576.

Keywords: HIV vaccines, gay men, sexual behaviors

The global HIV epidemic continues unabated1-3. Interventions to reduce HIV infection rates are promising4-8. However, topical and oral antiretrovirals for prevention may require daily adherence, a challenge for maintaining effectiveness. Male circumcision may be of limited benefit for female partners of HIV-infected men, men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug users. An effective HIV vaccine avoids some of these challenges and could provide synergy to existing strategies. The HIV vaccine field experienced a setback when the Step Study unexpectedly found that a replication-defective adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) vector vaccine with subtype B HIV-1 gag/pol/nef inserts appeared to increase the risk of HIV acquisition among MSM who were uncircumcised or had neutralizing antibodies to Ad5 at enrollment9. Additional analyses indicate that the vaccine-associated increased risk among these men was highest shortly after vaccination and then decreased after 18 months10.

A number of biological mechanisms for the increased HIV risk among these vaccinees have been proposed, such as increased trafficking of vector-specific T-cell lymphocytes to mucosal sites or boosting of CD4 positive T cells or Ad5-specific T cells11-16. Alternatively, the findings may be explained by differences in HIV exposure between vaccine and placebo recipients, particularly among men who were uncircumcised or had prior Ad5 immunity. Randomization is designed to eliminate imbalances in baseline characteristics by treatment arms17, and random allocation to treatment arms in the Step Study was stratified by prior Ad5 immunity but not by circumcision status9. Moreover, randomization does not preclude post-randomization differences in risk characteristics. Blinding, or keeping participants unaware of their treatment assignment, aims to limit exposure differences by treatment arm18. Unblinding of treatment assignment or perceptions of treatment assignment while blinded may contribute to changes in risk behaviors, leading to changes in exposure to HIV19.

We investigated whether differences in HIV exposure, as measured by reported sexual risk behaviors, and in perceived treatment assignment, may have contributed to the increased risk of HIV acquisition observed among vaccine compared to placebo recipients in the Step Study. We also determined if vaccine treatment assignment remained significantly associated with an increased risk of HIV infection, after controlling for sexual risk behaviors and other potential confounders. We also report on the role of insertive anal intercourse in the risk of HIV infection among uncircumcised men.

METHODS

The study design, procedures and primary results of the trial are previously published9.

Study design and population

This double-blind, phase II test-of-concept trial randomized 3000 HIV-1 negative participants aged 18-45 years in North America, Caribbean, South America, and Australia to receive three injections of MRKAd5 HIV-1 gag/pol/nef vaccine (n=1494) or placebo (n=1506). Men were eligible if they reported unprotected anal intercourse with a male partner or anal intercourse with two or more male partners and comprise this analysis sample9.

Procedures

Briefly, vaccine or placebo, in a 1:1 ratio, was given by injection at enrollment, week 4 and week 26. Randomization was pre-stratified by study site, sex and baseline Ad5 antibody titer, but not by circumcision status. Participants were considered to have prior Ad5 immunity at baseline if their Ad5 neutralizing titer was >18. In September 2007, the trial met prespecified futility boundaries at the first interim analysis and all immunizations were stopped9.

Risk behaviors in the previous 6 months were assessed by a standardized interviewer-administered questionnaire at screening and every 26 weeks. For sexual risk behaviors, participants were asked about the total number of male and female sexual partners and how many they knew were definitely HIV-infected, definitely not HIV-infected or not absolutely sure whether or not they were HIV-infected. Participants then were asked about occurrence of insertive and receptive anal intercourse (protected and unprotected) by serostatus of the male partners. These variables were used to construct variables of unprotected receptive/insertive anal intercourse with positive or unknown status partners. Participants also were asked about exchanging (giving and receiving) sex for money, drugs or services and frequency of crack cocaine, amyl nitrite and amphetamine use from “never” to “daily” on a 7-point response scale. Finally, evidence of sexually transmitted infection was recorded, including chlamydia or nonspecific urethritis, gonorrhea, syphilis, genital sores or ulcers or abnormal penile discharge.

Circumcision status was self-reported at the screening visit. Of 1,764 MSM enrolled, 1,148 (67.1%) rolled over to a follow-up protocol at the end of the Step Study and had their circumcision status assessed by physical examination. For 4 men, discrepancies between self-report and physical examination were found and the examination data were used.

Perceived treatment assignment was determined by asking the participant whether they thought they received vaccine, placebo or they were not sure. This question was asked at one study visit starting in mid-2007. Study sites implemented the question at different times and not all participants had the opportunity to answer the question. Thus, data for this variable were available for 1,370 (77.7%) of the men and the percent of participants with complete data varied by site.

HIV-1 infection status was determined at enrollment and at weeks 12, 30, and 52 and every 26 weeks thereafter. Specimens were screened with an immunoassay (Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV test, Trinity BioTech, Jamestown, NY, USA; or the Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Test, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Reactive tests were confirmed with an HIV-1 Western blot and HIV-1 plasma viral RNA assay (Amplicor Monitor version 1.5, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). A blinded endpoint adjudication committee made the final identification of HIV-1 infection status.

All participants provided written informed consent. Human experimentation guidelines of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and those of the authors’ institutions were followed. The protocol was approved by the institutional or ethics review committee at every site and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00095576.

Analysis objectives

The primary goal of these analyses was to determine whether differences in HIV exposure, as measured by self-reported sexual risk behaviors, may have contributed to the increased risk of HIV among MSM who were uncircumcised, had prior Ad5 immunity or were both uncircumcised and had prior Ad5 immunity. Demographics and self-reported risk behaviors at baseline and follow-up were compared between vaccine and placebo recipients among MSM who were uncircumcised, had prior Ad5 immunity or were both uncircumcised and had prior Ad5 immunity. Perceived treatment assignment among vaccine and placebo recipients was compared among the same three groups of MSM. We determined if vaccine treatment assignment remained significantly associated with an increased risk of HIV infection, after controlling for sexual risk behaviors, perceived treatment assignment and other potential confounders. Finally, we examined the role of insertive anal intercourse in the risk of HIV infection among uncircumcised men.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were based on MSM who were HIV-uninfected at study entry and who received at least one vaccination (modified intent to treat cohort). Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test were used to statistically test differences in categorical variables between groups. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to evaluate differences between groups in the distribution of number of sexual partners.

The generalized estimating equation approach for logistic regression was used to determine differences in risk behavior change by treatment arm. This method accounts for within-person variation over time and the correlation between the intervention-induced changes within an individual. The p-values in the table are based on a test for differences between overall trend from baseline to 18 months by treatment arm for each outcome.

We used multivariate Cox models to estimate the vaccine effect on HIV incidence. The time-to-event variable for the Cox models was defined as the time from first vaccination to the midpoint between the date of the last HIV-1 seronegative visit and the date of the first evidence of HIV-1 infection. Participants who never showed any evidence of HIV-1 infection were right censored on the date of their last study visit before October 17, 2007. The covariates included were age (≤30 vs. >30), race (white vs otherwise), region (North America, Australia or otherwise), baseline Ad5 titre (≤ 18 vs. >18), perceived treatment (Vaccine, Placebo, Not Sure, Missing), circumcision status, time-dependent drug use factors, and time-dependent sexual risk behaviors. For this analysis, time-dependent variables were utilized to allow for changes in risk behaviors over time. The potential confounders were all dichotomous for simplicity, stabilizing the model fitting, and reducing the modeling assumptions.

Cox models also were constructed among uncircumcised men to examine the role of insertive anal intercourse in the risk of HIV infection. In the first model, the baseline variable for unprotected insertive anal sex variable was included in the model to reflect the potential risk around the time of vaccine administration. In the second model, the time-dependent variable was included to allow for changes in risk behavior over the entire time of follow-up.

Role of funding source

The sponsors of the study were involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, and in the decision to submit for publication. The sponsors had full access to all the data in the study and shared final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Study sample

From December 2004 through March 2007, 1,764 MSM participants were randomized. The median age of the participants was 30 years. About half of the men (51.4%) were white and 29.0% were of multiracial identity, mostly from South America. Over half of the men (56.5%) were circumcised and 56.3% were Ad5 seropositive at baseline. At baseline, the median number of male sex partners in the prior six months was 6 (25%, 75%tiles: 3, 15). About one-quarter (24.4%) of men reported having a known HIV-infected partner. Unprotected receptive and insertive anal intercourse in the previous six months was reported by 49.1% and 59.8% of men, respectively. Amyl nitrite (“poppers”) was used by 16.2% of men and amphetamines by 6.3%. Exchange of sex for money, drugs or other services was reported by 16.7% of men and a recent STI was reported by 12.3%. Among 1,764 MSM, 726 were uncircumcised (vaccine: 360; placebo: 366), 994 had prior Ad5 immunity (vaccine: 497; placebo: 497) and 563 were both uncircumcised and had prior Ad5 immunity (vaccine: 276; placebo: 287).

Baseline and follow-up risk behaviors among vaccine and placebo recipients

Demographics and self-reported risk behaviors at baseline were compared between vaccine and placebo recipients among uncircumcised men, those with prior Ad5 immunity and uncircumcised men with prior Ad5 immunity (Table 1). Few significant differences were observed and the differences were small in proportion. Among uncircumcised men, vaccine recipients were more likely to report unprotected insertive anal intercourse with HIV negative partners (24.9% vs. 18.1%; p=0.03), but were less likely to report genital sore or ulcers (0.3% vs. 2.2%; p=0.04). Among uncircumcised men who had prior immunity to Ad5, vaccine recipients were more likely to report unprotected insertive anal intercourse with partners of unknown HIVstatus (46.0% vs. 37.8%; p=0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics and self-reported behaviors in prior 6 months between treatment arms at baseline among uncircumcised men and men with pre-existing immunity to Ad5, Step Study

| Uncircumcised men (n=726) |

Ad5 titer >18 (n=994) |

Uncircumcised and Ad5 titer >18 (n=563) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Va (n=360) |

Pa (n=366) |

p-valueb | V (n=497) |

P (n=497) |

p-valueb | V (n=276) |

P (n=287) |

p-valueb | |

|

|

|||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 18-20 | 17.8 | 19.4 | 0.12 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 0.23 | 19.9 | 20.9 | 0.23 |

| 21-25 | 35.0 | 27.3 | 27.6 | 21.3 | 34.8 | 26.8 | |||

| 26-30 | 18.3 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 21.1 | 18.1 | 19.5 | |||

| 31-40 | 23.1 | 25.1 | 28.8 | 30.0 | 21.7 | 24.0 | |||

| 41-46 | 5.8 | 9.6 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 5.4 | 8.7 | |||

| Median age | 25 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 26 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 18.6 | 18.9 | 0.40 | 36.6 | 34.8 | 0.45 | 12.3 | 12.9 | 0.29 |

| Black | 6.1 | 6.0 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 5.4 | 5.2 | |||

| Hispanic | 7.8 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 10.1 | 7.3 | 10.1 | |||

| Multiracial | 65.3 | 60.4 | 44.7 | 43.3 | 73.6 | 67.9 | |||

| Other | 2.2 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 3.8 | |||

| Region | |||||||||

| North America/Australia | 26.9 | 26.8 | 1.00 | 49.7 | 50.3 | 0.90 | 17.4 | 19.9 | 0.45 |

| South America/Caribbean | 73.1 | 73.2 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 82.6 | 80.1 | |||

| Ad5 NAb titer | |||||||||

| ≤ 18 | 23.3 | 21.6 | 0.85 | -- | -- | 0.89 | -- | -- | 0.91 |

| 19-200 | 19.7 | 20.5 | 26.2 | 26.8 | 25.7 | 26.1 | |||

| >200 | 56.9 | 57.9 | 73.8 | 73.2 | 74.3 | 73.9 | |||

| Had female partners | 30.3 | 29.0 | 0.74 | 26.4 | 23.9 | 0.42 | 35.5 | 31.0 | 0.28 |

| Total male partners | |||||||||

| 1 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 0.75 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 0.69 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.56 |

| 2-4 | 33.1 | 32.8 | 36.0 | 33.0 | 35.5 | 31.0 | |||

| 5-9 | 22.8 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 24.8 | 23.6 | 25.1 | |||

| 10-19 | 13.9 | 16.1 | 13.3 | 15.5 | 12.3 | 16.7 | |||

| 20+ | 26.4 | 24.6 | 24.1 | 22.9 | 26.1 | 24.7 | |||

| Median (25, 75 percentile) | 6 (3,20) | 7 (3,18) | 6 (3,16) | 6 (3,15) | 6(3,20) | 7(4,18) | |||

| HIV+ male partner | 13.3 | 11.8 | 0.58 | 18.7 | 18.3 | 0.93 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 1.00 |

| No. HIV unknown status male partners |

|||||||||

| 0 | 19.4 | 18.0 | 0.95 | 18.7 | 21.3 | 0.42 | 18.8 | 17.4 | 0.90 |

| 1 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 9.5 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.3 | |||

| 2-4 | 28.6 | 27.3 | 30.2 | 27.2 | 30.8 | 27.9 | |||

| 5-9 | 16.7 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 16.3 | 18.1 | |||

| 10-19 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 9.7 | 12.1 | 10.1 | 12.5 | |||

| 20+ | 17.5 | 17.5 | 15.1 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 16.7 | |||

| Median (25, 75 percentile) | 4 (1,10) | 4 (1,10) | 3(1,9) | 4(1,10) | 4(1,10) | 4(2,10) | |||

| No. HIV negative male partners |

|||||||||

| 0 | 56.7 | 62.8 | 0.53 | 54.9 | 55.9 | 0.56 | 58.0 | 61.0 | 0.93 |

| 1 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | |||

| 2-4 | 15.0 | 13.9 | 17.9 | 17.1 | 15.2 | 13.2 | |||

| 5-9 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 6.9 | 7.7 | |||

| 10-19 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 5.2 | |||

| 20+ | 6.4 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 7.3 | 5.6 | |||

| Median (25, 75 percentile) | 0(0,3) | 0 (0,2) | 0(0,3) | 0(0,3) | 0(0,3) | 0(0,3) | |||

| Unprotected insertive anal with… |

|||||||||

| HIV positive partners | 5.8 | 6.3 | 0.88 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 0.90 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 1.00 |

| HIV unknown status partners |

43.5 | 38.4 | 0.16 | 42.4 | 37.0 | 0.08 | 46.0 | 37.8 | 0.05 |

| HIV negative partners | 24.9 | 18.1 | 0.03 | 24.5 | 23.3 | 0.71 | 24.1 | 18.3 | 0.10 |

| Unprotected receptive anal with… |

|||||||||

| HIV positive partners | 3.3 | 3.3 | 1.00 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 0.21 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.00 |

| HIV unknown status partners |

33.4 | 38.1 | 0.21 | 34.6 | 34.1 | 0.89 | 36.2 | 38.5 | 0.60 |

| HIV negative partners | 21.0 | 19.2 | 0.58 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 0.94 | 19.3 | 20.6 | 0.75 |

| Exchange of sex | 26.9 | 29.0 | 0.56 | 23.7 | 25.2 | 0.66 | 31.9 | 32.8 | 0.85 |

| Received payment for sex |

24.8 | 27.4 | 0.45 | 21.5 | 23.2 | 0.54 | 29.0 | 31.1 | 0.65 |

| Paid for sex | 5.3 | 4.1 | 0.49 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 0.48 | 6.6 | 4.2 | 0.26 |

| Sexually transmitted infections |

|||||||||

| Any | 11.9 | 9.8 | 0.40 | 11.9 | 9.3 | 0.22 | 10.5 | 8.4 | 0.39 |

| Chlamydia/NSU/NGU | 1.4 | 2.7 | 0.30 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.16 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.55 |

| Gonorrhea | 3.4 | 1.9 | 0.25 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 0.27 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.77 |

| Syphilis | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.29 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.77 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.45 |

| Other | 5.9 | 3.3 | 0.11 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 0.06 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 0.12 |

| Genital sores/ulcers | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.27 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.07 |

| Substance use | |||||||||

| Injection drug use | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.00 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.23 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.00 |

| Poppers | 6.4 | 8.0 | 0.47 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 0.70 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 0.37 |

| Amphetamines | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.49 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 0.46 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 0.25 |

| Ecstasy | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.72 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.82 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.00 |

| Crack cocaine | 1.7 | 3.6 | 0.16 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 0.50 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 0.14 |

V=vaccine; P= placebo

p-value compared vaccine to placebo

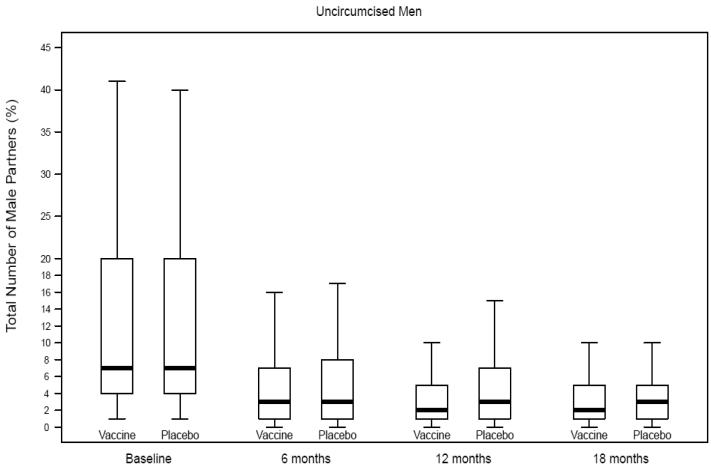

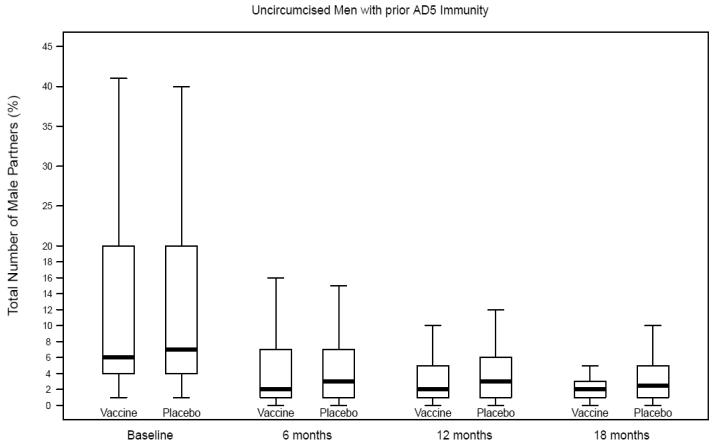

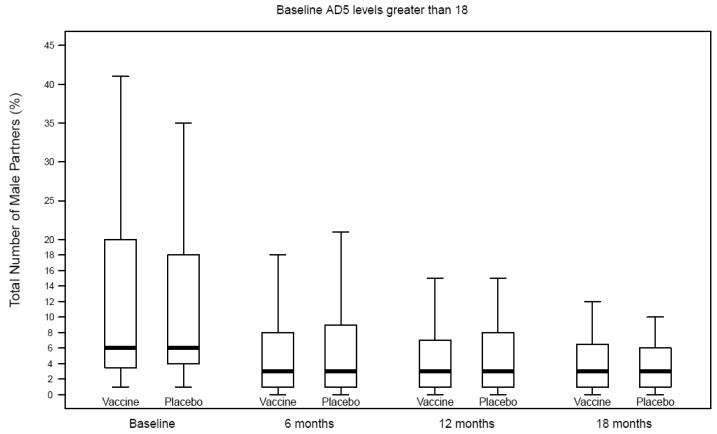

Self-reported risk behaviors during follow-up were compared between vaccine and placebo recipients among uncircumcised men, those with prior Ad5 immunity and uncircumcised men with prior Ad5 immunity (Table 2; Figures 1A-C). Only one comparison reached statistical significance and it was not in the direction to explain the increased risk of HIV infection among vaccine recipients. That is, among uncircumcised men who had prior Ad5 immunity, vaccine recipients had a greater decline in reporting of unprotected receptive anal intercourse with unknown status partners compared to placebo recipients.

Table 2.

Comparison of change in risk behaviors between treatment arms among uncircumcised men and men with pre-existing immunity to Ad5, Step Study

| Uncircumcised men (n=724) | Ad5 titer >18 (n=994) | Uncircumcised and Ad5 titer >18 (n=560) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Va (n=358) |

Pa (n=366) |

p-valueb | V (n=497) |

P (n=497) |

p-valuea | V (n=274) |

P (n=286) |

p-valuea | |

|

|

|||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| HIV+ partner | |||||||||

| Baseline | 13.6 | 11.7 | 19.2 | 18.3 | 9.4 | 9.4 | |||

| Month 6 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 14.1 | 18.5 | 6.7 | 8.3 | |||

| Month 12 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 15.6 | 5.3 | 6.1 | |||

| Month 18 | 6.3 | 4.4 | .35 | 13.4 | 12.5 | .76 | 5.6 | 2.4 | .08 |

| Unprotected receptive anal intercourse with HIV positive partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | |||

| Month 6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | |||

| Month 12 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |||

| Month 18 | 0.7 | 1.9 | .41 | 2.5 | 2.4 | .37 | 0.9 | 0.8 | .95 |

| Unprotected receptive anal intercourse with HIV unknown status partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 33.4 | 38.1 | 34.6 | 34.1 | 36.2 | 38.2 | |||

| Month 6 | 13.9 | 16.3 | 15.0 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 15.5 | |||

| Month 12 | 13.9 | 21.5 | 15.2 | 19.7 | 15.0 | 23.9 | |||

| Month 18 | 15.3 | 21.4 | .19 | 15.8 | 18.7 | .12 | 15.9 | 23.0 | .05 |

| Unprotected receptive anal intercourse with HIV negative partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 20.9 | 19.2 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 19.3 | 20.7 | |||

| Month 6 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 15.3 | 17.7 | 11.7 | 13.0 | |||

| Month 12 | 11.1 | 9.4 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 10.2 | 9.6 | |||

| Month 18 | 14.6 | 11.3 | .50 | 14.9 | 16.3 | .86 | 15.0 | 9.5 | .14 |

| Unprotected insertive anal intercourse with HIV positive partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 5.8 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 3.6 | 3.8 | |||

| Month 6 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 1.1 | |||

| Month 12 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | |||

| Month 18 | 0.0 | 1.9 | .69 | 5.4 | 4.3 | .52 | 0.0 | 0.8 | .74 |

| Unprotected insertive anal intercourse with HIV unknown status partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 43.5 | 38.4 | 42.5 | 37.0 | 46.0 | 37.5 | |||

| Month 6 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 17.8 | 16.8 | 13.3 | 12.5 | |||

| Month 12 | 14.6 | 17.8 | 16.0 | 17.0 | 14.1 | 15.7 | |||

| Month 18 | 9.0 | 9.4 | .09 | 15.8 | 11.5 | .44 | 8.4 | 8.7 | .08 |

| Unprotected insertive anal intercourse with HIV negative partners |

|||||||||

| Baseline | 24.9 | 18.1 | 24.5 | 23.3 | 24.1 | 18.3 | |||

| Month 6 | 13.3 | 10.4 | 17.9 | 17.0 | 11.3 | 10.0 | |||

| Month 12 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 16.0 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 8.3 | |||

| Month 18 | 13.2 | 11.9 | .78 | 15.3 | 16.3 | .96 | 9.3 | 9.5 | .89 |

| Exchange sex | |||||||||

| Baseline | 26.9 | 29.0 | 23.7 | 25.2 | 31.8 | 32.9 | |||

| Month 6 | 14.8 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 17.2 | 12.5 | |||

| Month 12 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 15.0 | 14.3 | |||

| Month 18 | 9.1 | 15.6 | .79 | 6.0 | 12.0 | .46 | 9.4 | 17.5 | .72 |

| Used poppers | |||||||||

| Baseline | 6.4 | 8.0 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 4.7 | 6.7 | |||

| Month 6 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 4.2 | 4.9 | |||

| Month 12 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 3.9 | 5.2 | |||

| Month 18 | 5.6 | 5.7 | .48 | 9.0 | 8.2 | .71 | 2.8 | 6.5 | .95 |

| Used amphetamines | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3.1 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 5.5 | |||

| Month 6 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 3.7 | |||

| Month 12 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 3.8 | |||

| Month 18 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 0.77 | 4.0 | 2.9 | .21 | 2.8 | 2.9 | .82 |

V=vaccine; P= placebo

p-value denotes the difference in the log(OR) of the Month 18 vs Baseline between vaccine and placebo groups

Figure 1A.

Number of male partners among uncircumcised men, Step Study

Figure 1C.

Number of male partners among uncircumcised men with prior Ad5 immunity, Step Study

Perceived treatment assignment among vaccine and placebo recipients

Among uncircumcised men, 26.0% of vaccine recipients believed they had received vaccine compared to 19.3% of placebo recipients (OR = 1.5; 95% CI:1.0,2.2). Similarly, among men with prior Ad5 immunity, 26.6% of vaccine recipients believed they had received vaccine compared to 19.3% of placebo recipients (OR = 1.5; 95% CI:1.1,2.1). For men who were both uncircumcised men and had prior Ad5 immunity, 24.5% of men who received vaccine believed they got vaccine compared to 16.5% of those who received placebo (OR = 1.7; 95% CI:1.0,2.6). The largest difference in perceived treatment between vaccine and placebo recipients was among circumcised men with a baseline Ad5 titer of ≤18, the group without evidence of an increased risk of HIV infection among vaccinees: 39.0% of men who received vaccine believed they got vaccine compared to 15.4% of men who received placebo (OR = 3.5; 95% CI:2.3,5.4).

Multivariate analysis of HIV infection

In univariate analysis of HIV acquisition, the hazard ratio for treatment assignment was 1.5 (95% CI:0.9,2.3) (Table 3). Other variables associated with HIV acquisition were geographic region, 20+ male sex partners, unprotected receptive or insertive anal intercourse with positive or unknown status partners and use of poppers or amphetamines. Controlling for geographic region, age, Ad5 titer, circumcision status and perceived treatment, the hazard ratio for treatment assignment in the first multivariate model increased to 2.5 (95% CI:1.1,5.7). Controlling for time-dependent sexual risk behaviors and drug use (multivariate model 2), vaccine recipients remained at higher risk of HIV infection compared to placebo recipients (HR = 2.8; 95% CI:1.7,6.8). Including age and number of partners as continuous variables did not change the results of the model. No significant interactions between any sexual risk behaviors and treatment assignment were found, suggesting that the risk of HIV infection among vaccine compared to placebo recipients did not differ between those reporting specific sexual risk behaviors and those who did not.

Table 3.

Analysis of predictors of HIV-1 acquisition, STEP Study

| Univariate | Multivariate Model 1 | Multivariate Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) |

| Treatment Group (Ref: Placebo) | 1.45 | (0.93, 2.26) | 2.48 | (1.08,5.69) | 2.79 | (1.16,6.75) |

| Region (Ref: South America) | 1.76 | (1.00, 3.09) | 2.56 | (1.18,5.56) | 1.93 | (0.84,4.45) |

| Circumcision status (Ref: uncircumcised) |

1.16 | (0.72, 1.85) | 1.27 | (0.52,3.07) | 1.77 | (0.69,4.54) |

| Ad5 titer (Ref: <18) | 1.00 | (0.64, 1.57) | 1.23 | (0.76,1.99) | 1.44 | (0.87,2.37) |

| Age (Ref: ≥30 years) | 1.29 | (0.83, 2.00) | 1.55 | (0.97,2.49) | 1.70 | (1.04,2.77) |

| Interaction: Treatment Group x Circumcision status |

0.45 | (0.16,1.21) | 0.39 | (0.14,1.10) | ||

| Perceived trt: Not Sure: Vaccine | 0.75 | (0.40, 1.40) | 0.79 | (0.42,1.50) | 0.74 | (0.39,1.40) |

| Perceived trt: Placebo: Vaccine | 0.82 | (0.43, 1.57) | 0.88 | (0.45,1.72) | 0.83 | (0.42,1.62) |

| Perceived trt: Missing: Vaccine | 1.83 | (0.98, 3.42) | 1.80 | (0.95,3.40) | 1.46 | (0.75,2.84) |

| 20+ male sex partnersa | 2.59 | (1.61, 4.18) | 2.02 | (1.19,3.43) | ||

| Unprotected receptive anal sex with positive/unknown partnersa |

2.61 | (1.65, 4.13) | 1.92 | (1.11,3.33) | ||

| Unprotected insertive anal sex with positive/unknown partnersa |

2.22 | (1.41, 3.48) | 1.16 | (0.67,2.02) | ||

| Poppersa | 1.88 | (1.11, 3.18) | 0.81 | (0.43,1.54) | ||

| Speeda | 4.59 | (2.65, 7.97) | 3.43 | (1.80,6.55) | ||

time-dependent variables

HR = hazard ratio

Additional analyses were conducted among uncircumcised men. If an increased risk of HIV infection due to the vaccine was related to being uncircumcised, the effect of the vaccine on HIV infection would likely have been higher among uncircumcised men reporting unprotected insertive anal sex around the time of vaccine administration compared to men not reporting unprotected insertive anal sex at that time. We found that the hazard ratio for HIV infection for vaccine compared to placebo recipients was 4.4 (95% CI:1.2,15.3) among uncircumcised men reporting unprotected insertive anal sex at baseline, while the hazard ratio among uncircumcised men who reported no insertive anal sex at baseline was 1.2 (95% CI:0.3,4.1). Taking into account time-dependent behaviors, the hazard ratio for HIV infection for vaccine compared to placebo recipients was 2.3 (95% CI:0.6, 8.8) among uncircumcised men reporting unprotected insertive anal sex while the hazard ratio among uncircumcised men who reported no insertive anal sex was 2.4 (95% CI:0.9, 7.0).

DISCUSSION

This analysis focused on whether the increased risk of HIV infectin observed among subgroups of men in the Step Study (uncircumcised men and men with prior Ad5 immunity who received vaccine) could be explained by any differences in risk behaviors or perceptions of treatment assignment. Differences would suggest that exposure to HIV was not equal in the two arms of the study, potentially affecting HIV incidence rates. The differences in risk behaviors found in this analysis were few in number, and of those differences identified, the magnitude of differences was small.

We also assessed whether perception of vaccination status could explain any differences in HIV exposure. We found that uncircumcised men who had prior immunity to Ad5 and had received vaccine were 1.7 times more likely to think that they got vaccine than placebo recipients. If this group of men increased their risk due to a perception of protection from the vaccine, HIV infection rates could have been elevated in this group. However, we did not find any significant differences in risk behaviors between vaccine and placebo recipients in this group. Furthermore, adjustment for these differences in Cox regression analysis did not eliminate the significant association of vaccine with increased risk of HIV infection. In fact, it was the vaccine recipients who were circumcised and Ad5 negative at baseline who were over three times more likely to think they had gotten vaccine, an effect much stronger than among uncircumcised men. There is evidence that persons who do not have prior Ad5 immunity have greater reactogenicity to rAd5 vaccines20. Thus, these men may not have actively unblinded themselves by HIV testing outside of the study, but had greater systemic reactions which led them to believe that they had gotten vaccine. This group, however, did not have higher HIV incidence rates than placebo controls.

We examined whether treatment assignment remained significantly associated with HIV infection controlling for circumcision status, Ad5 status, perceived treatment and risk behaviors. The association between HIV infection and treatment assignment could not be explained by behavioral variables or other potential confounders. There were no significant interactions between behavior and treatment arm.

Finally, a biologic mechanism is suggested by our analysis of uncircumcised men, unprotected insertive anal sex and risk of infection associated with vaccine. Men reporting unprotected insertive anal sex at baseline and thus close to the time of vaccine administration demonstrated an increased risk of infection associated with vaccine. This increased risk was not seen among men who did not report unprotected insertive anal sex nor did we see such differences using a variable which took into account the reporting of unprotected insertive anal sex over 18 months of the study (time-dependent variables). This finding is consistent with other analyses from the Step Study indicating that the increased risk of HIV infection associated with vaccine appeared to highest around the time of vaccination and then decreased after 18 months10. It is possible that any inflammation in the foreskin area related to the time of vaccine administration could have increased the risk of HIV acquisition21.

These data have limitations. Behaviors were collected in face-to-face interviews and thus, some behaviors may have been underreported. However, since all study staff were blinded to treatment assignment, there is no reason to believe that the data collected would have been biased by treatment arm. Most of behavioral measures were limited to binary outcomes and number of episodes of risk behaviors were not collected. Finer gradations may have revealed more subtle effects of behavioral risk. Finally, perceived treatment assignment was not available for 22% of participants, although they were included in the analyses as “missing”.

In sum, these analyses do not support a behavioral explanation for the observed increased HIV infection rates among uncircumcised men or men with prior Ad5 immunity in the Step Study. The results of the Step Study emphasize the critical need for effective, sensitive measures of behaviors and attention to perception of treatment assignment in biomedical trials so unexpected findings such as those in the Step Study can be properly examined. Identifying biologic mechanisms to explain the increased HIV infection risk is a priority.

Figure 1B.

Number of male partners among men with prior Ad5 immunity, Step Study

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by Merck Research Laboratories; the Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in the US National Institutes of Health (NIH); the NIH-sponsored HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN); and the Center for AIDS Research Center Grant number 1P01 AI057127 to the NYU School of Medicine from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Author contributions: SPB and MNR participated in the design of the study. SPB and MNR co-chaired the study and oversaw study implementation. BAK, KHM, JS, MM, SJB, PR and SPB participated in the conduct of the study. LN and C-YW analyzed the study data. BAK and SPB drafted the report, and all co-authors participated in revising the report.

Conflicts of interest MNR is a paid employee of Merck, owns Merck stock and has Merck stock options. BAK, KHM, JS, MM, SJB and SPB served as investigators on Merck-funded research. LN, and C-YW declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- (1).Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, et al. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2007;21:2513–2520. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2704a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).van GF, de Lind van Wijngaarden JW. A review of the epidemiology of HIV infection and prevention responses among MSM in Asia. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 3):S30–S40. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390087.22565.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Abdool KQ, bdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N Engl J Med. 2010 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Templeton DJ. Male circumcision to reduce sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:344–349. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a46d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Duerr A, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, et al. Extended follow-up confirms early vaccine-enhanced risk of HIV acquisition and demonstrates waning effect over time among participants in a randomized trial of recombinant adenovirus HIV vaccine (Step Study) J Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis342. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gray G, Buchbinder S, Duerr A. Overview of STEP and Phambili trial results: two phase IIb test-of-concept studies investigating the efficacy of MRK adenovirus type 5 gag/pol/nef subtype B HIV vaccine. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:357–361. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833d2d2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Masek-Hammerman K, Li H, Liu J, et al. Mucosal trafficking of vector-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes following vaccination of rhesus monkeys with adenovirus serotype 5. J Virol. 2010;84:9810–9816. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chakupurakal G, Onion D, Cobbold M, Mautner V, Moss PA. Adenovirus vector-specific T cells demonstrate a unique memory phenotype with high proliferative potential and coexpression of CCR5 and integrin alpha4beta7. AIDS. 2010;24:205–210. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333addf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hutnick NA, Carnathan DG, Dubey SA, et al. Baseline Ad5 serostatus does not predict Ad5 HIV vaccine-induced expansion of adenovirus-specific CD4+ T cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:876–878. doi: 10.1038/nm.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Benlahrech A, Harris J, Meiser A, et al. Adenovirus vector vaccination induces expansion of memory CD4 T cells with a mucosal homing phenotype that are readily susceptible to HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19940–19945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907898106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).O’Brien KL, Liu J, King SL, et al. Adenovirus-specific immunity after immunization with an Ad5 HIV-1 vaccine candidate in humans. Nat Med. 2009;15:873–875. doi: 10.1038/nm.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359:515–519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bartholow BN, Buchbinder S, Celum C, et al. HIV sexual risk behavior over 36 months of follow-up in the world’s first HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:90–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143600.41363.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Priddy FH, Brown D, Kublin J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a replication-incompetent adenovirus type 5 HIV-1 clade B gag/pol/nef vaccine in healthy adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1769–1781. doi: 10.1086/587993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK. Interactions of HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases, and genital tract inflammation facilitating local pathogen transmission and acquisition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:308–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]