Abstract

Women’s choice and control impact birthing experiences. This study used a qualitative, descriptive approach to explore how women develop their initial birth plan and how changes made to the plan affect overall birth experiences. Narrative, semistructured interviews were conducted with 15 women who had given birth in Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada, and data were analyzed using a phenomenological approach. Findings showed that women relied on many resources when planning a birth and that changes made to a woman’s initial birth plan affected her recollection of the birth experience. Conclusions are that women’s positive and negative recollections of their birth experiences are related more to feelings and exertion of choice and control than to specific details of the birth experience.

Keywords: childbirth, choice in childbirth, control in childbirth, birth narrative

The birth of a child is a pivotal time in the life of a mother and her family. The health and well-being of a mother and child at birth largely determines the future health and wellness of the entire family (World Health Organization [WHO], 2005). The outcome of childbirth, however, is not the only factor of importance in a mother’s well-being. Some research suggests that the way in which a woman experiences pregnancy and childbirth is also vitally important for a mother’s relationship with her child and her future childbearing experiences (Fox & Worts, 1999; Hauck, Fenwick, Downie, & Butt, 2007). The current study explored how women develop a birth plan and the ways in which changes to the initial plan affect a woman’s description of the birth experience.

In preparing to give birth, women, knowingly or unknowingly, develop a birth plan. The use of formal birth plans developed in the 1980s as a way for women to engage in discussion with their care providers and to articulate their desired birth experience (Kuo et al., 2010). Birth plans generally include information such as where a woman wishes to give birth, who will attend a birth, and what forms of medical intervention and pain relief will be used. The birth plan is a tool that outlines a woman’s expectations for her birth and can open communication between a woman and her care providers, providing the woman with knowledge prior to giving birth (Doherty, 2010; Kuo et al., 2010; Pennell, Salo-Coombs, Herring, Spielman, & Fecho, 2011). There may also be negative outcomes of developing a birth plan; for example, feelings of failure if the birth plan is not followed and disappointment with the birth experience if expectations are not met (Berg, Lundgren, & Lindmark, 2003; Lundgren, Berg, & Lindmark, 2003).

The birth plan is a tool that outlines a woman’s expectations for her birth and can open communication between a woman and her care providers, providing the woman with knowledge prior to giving birth.

When negotiating birth plan decisions, women tend to alter their expectations to avoid disappointment (Hauck et al., 2007). When expectations are altered, the care providers and support team become vitally important in helping to negotiate changes and foster a positive birth experience (Hauck et al., 2007). For the purposes of this study, we defined a woman’s “care team” or “support team” as all individuals who assist with planning and giving birth, including obstetricians, midwives, nurses, doulas, friends, family members, and the woman’s partner, all of whom may shape a woman’s thinking about planning a birth. The literature suggests that there is a constant negotiation of expectations and desires for the birth between a woman and her support team (Doherty, 2010). During both the development and implementation of the birth plan, women must negotiate their expectations and make health decisions with their care providers. The role of the care provider is central in the ways in which women make decisions. One study suggests that nurses can have an impact on women’s feelings of confidence and the birth-related decisions they make (Carlton, Callister, & Stoneman, 2005). Furthermore, a recent study by Klein et al. (2011) revealed that younger obstetricians were significantly more likely to favor the routine use of epidurals and were more likely to view cesarean surgery as a feasible solution to many problems that can arise during childbirth. The ways in which an obstetrician views birth impacts the options that are presented to women (by their obstetrician, their nurse, or other care provider) and the decisions that a woman makes before and during childbirth.

The ways in which women make general health-related choices inform decisions they make concerning childbirth. One conceptualization of women’s health decision making is the Wittmann-Price (2004, 2006) model of “emancipated decision making.” This model has five dimensions: reflection, empowerment, personal knowledge, social norms, and a flexible environment (Kovach, Becker, & Worley, 2004; Noone, 2002; Wittmann-Price, 2004). Reflection is the process of questioning common practices that are based solely on authority or tradition (Wittmann-Price, 2004). This questioning is important for the individual to critically analyze both personal and professional information. Empowerment that is derived from knowledge promotes autonomy and independence and is also an important aspect of emancipated decision making (Wittmann-Price, 2004). Personal knowledge, social norms, and flexible environment are described as most closely linked to a woman’s satisfaction with her decisions (Wittmann-Price, 2006). This model is used as a template in the current study for understanding women’s decisions related to the chosen birth method and subsequent birth experience. Given the broad nature of the Wittmann-Price model of health-related decisions, it is helpful for understanding the negotiation that takes place during labor and birth.

Several factors contribute to women’s retrospective attitudes toward their birth experience. The most prominent factors include control, choice in decision making, social support, and efficacy of pain control (Fox & Worts, 1999; Gibbins & Thomson, 2001; Hardin & Buckner, 2004; Howell-White, 1997; McCrea & Wright, 1999; Waldenström, Hildingsson, Rubertsson, & Rådestad, 2004). Women define control as consisting of internal and external processes, both of which impact their feelings about the overall birth experience. Internal control refers to a woman’s ability to control her feelings and expressions of pain and to make bodily decisions (e.g., changing position freely) during labor (Hardin & Buckner, 2004; McCrea & Wright, 1999). External control, on the other hand, refers to a woman’s ability to take part in decision making concerning her birth, including medical interventions, sources and types of support, and where and how to give birth (Hardin & Buckner, 2004; McCrea & Wright, 1999). A lack of control is more likely to be associated with a negative childbirth experience, whereas feelings of both internal and external control are associated with a positive experience (Hardin & Buckner, 2004). During birth, the development and negotiation of control are part of a dialectical process between a woman and her care team.

The purpose of this study was to better understand the overall role of choice and control in women’s childbirth experiences. This study explored how women develop and negotiate their initial birth plan and how subsequent changes made to the plan affect overall birth experiences.

During birth, the development and negotiation of control are part of a dialectical process between a woman and her care team.

METHOD

This study implemented a one-group qualitative, descriptive design using narrative method of data collection. A narrative approach allows women to tell their stories, emphasizing parts they deem most important. This study was approved by the research ethics board at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada. Participants were recruited using convenience and snowball sampling strategies; individuals in the study were asked to talk about this study with similar others and invite them to participate. The inclusion criterion was that women must have given birth in the geographical bounds of the study during the previous 2 years. The rationale for this time frame was to speak with women who were still processing their birth or having near recent insights and reflections. The study was advertised at a local organization through a program called the Breastfeeding Buddies Support Group. This organization was chosen based on existing professional relationships rather than sample characteristics. A nurse practitioner assisted with recruitment and snowball sampling.

The sample comprised 15 women: 47% had one pregnancy and birth (primiparous), 13% were pregnant with their second child, and 40% were multiparous (those who have experienced more than one pregnancy and birth). All participants initiated breastfeeding with their infant(s) and all had a partner involved in the birth of their child(ren). In terms of care providers for the birth, 87% of participants (n = 13) used a midwife, one participant pursued the care of a general practitioner, and another employed the care of an obstetrician. Five of the 15 participants hired a labor doula for their birth(s). Demographic information pertaining to participants’ births was collected during the interview; however, no further demographic information was collected.

Data were collected through in-depth, unstructured, individual interviews using a guide with sections that inquired about the birth plan development, birth story (stories)/experiences, and reflections about how what happened (the reality) differed from the plan. All interviews began with a general description of the project, followed by an elaboration of two specific interview topics about their birth plan(s)—or lack of a birth plan—and their birthing experience(s). Then, participants were asked to begin telling their story, choosing whichever topic they felt most comfortable with beginning the interview. Later, the interviewer probed for the other topic. The duration of interviews ranged from 45 min to 2 hr, varying in length because of the diversity and complexity of birth stories and the conditions of the interviews. Interviews were conducted at a convenient time and place for the participants, often in their homes and sometimes with children present, as expected.

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim solely by the principal researcher/first author. Data were analyzed and coded using a phenomenological approach and managed using NVivo software. Codes were developed using the various parts of the birth story as a guide; for example, planning, changes to birth plan, decision making during birth, support during birth, and breastfeeding support. In the next step, these codes were analyzed further to gain a better understanding of how women constructed their experiences and which aspects of these experiences were emphasized by participants. In the “Findings” section of this article, pseudonyms are used to refer to participants individually to protect their anonymity and refer to them using names, rather than the impersonal nature of participant numbers.

Several measures were taken to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. To bolster the credibility of the data, the principal researcher kept an audit trail throughout the course of the study. This was accomplished by keeping a journal of the research process. The journal served to document the process of the research as well as the principal researcher’s developing thoughts and reflections with regards to the process. During data analysis, attention was paid to cases that negated the developing understanding of women’s experiences of childbirth. The principal researcher remained cognizant of possible negative cases to ensure that all possibilities were considered throughout the process of analyzing the data. Because the data are descriptions of each participant’s experiences with such a unique and complex nature, attention to negative cases was extremely pertinent to this study’s trustworthiness.

FINDINGS

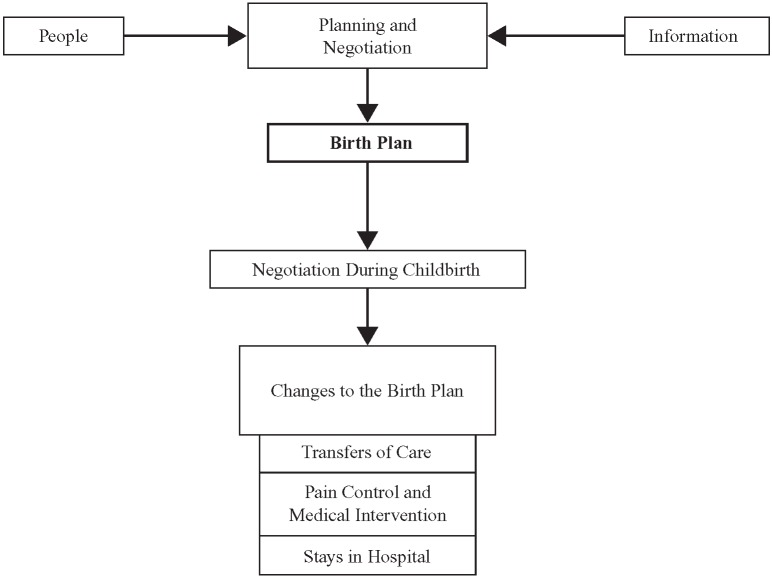

Our report of the findings from this study are organized into two sections in subsequent paragraphs. The first section describes the ways in which women planned their birth experience and how they negotiated these health-related decisions with their support teams. The second section describes changes to the birth plan and how these changes affected the women’s birth experience. Changes to the birth plan took three main forms: (a) transfers of care, in terms of care provider and/or place of labor and birth; (b) the level and type of medical intervention used; and (c) stays in the hospital. Table 1 presents a summary of the birth choices that women made and the actual birth experiences women had in terms of their attending care providers and place of birth. The purpose of this table is to provide the reader with a better understanding of the choices that the women made prior to giving birth and how their plans changed for individual participants. Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of our study’s main findings.

TABLE 1. Participant Summary Table.

| Participant | Number of Births | Midwife | OB | GP | Doula | Home Birth | Hospital Birth |

| 1. Katrina | 1 | X → | X | X | |||

| 2. Marlene | 1 | X | X | ||||

| 3. Thelma | 1 | X | X | X | |||

| 4. Melody | 1 | X | X | ||||

| 5. Selah | 2 (twins) | X → | X | X | |||

| 6. Marcy | 3 | X → | X | X | X → | X | |

| 7. Carlaa | 2 | X | X | X | X | ||

| 8. Joni | 2 | X → | X | X → | X | ||

| 9. Regina | 1 | X → | X | X | X → | X | |

| 10. Tessa | 1 | X → | X | X | |||

| 11. Ellab | 1 (pregnant) | X | X | ||||

| 12. Jenna | 4 | X | X | ||||

| 13. Paigeb | 1 (pregnant) | X | X | X | |||

| 14. Shelly | 1 | X | X | ||||

| 15. Lara | 3 | X | |||||

| Total | 13 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 5 (actual) | 11 |

Note. An arrow (→) indicates a transfer of care. OB = obstetrician; GP = general practitioner.

aThis participant had more than one child and experienced midwifery care and obstetrician care for subsequent births. bThese two participants were pregnant at the time of the interview and therefore discussed their experiences with planning two births.

Figure 1.

Visual model depicting the study’s main findings.

Planning and Negotiation

When planning a birth, the women in our study noted two types of resources that influenced their decision-making process: people and information. Individuals involved were based on social relations (e.g., a woman’s partner or mother) or professional roles such as care providers (e.g., midwife, physician). Overall, women wanted to share the planning and birthing experience with their partners and to incorporate their partner’s wishes into the birth plan. Some partners directly influenced decisions made, whereas others did not contribute to the plan per se but played the role of supporting a woman’s decisions. For example, Lara recalled her decision to have a home birth: “My husband is not a big fan of hospitals either, so it was, so he had a bit of a say in it too and I thought we’d try to make it as comfortable as possible.” Another participant described a similar partner role:

With my husband . . . I mean, he was very good at reading up on stuff, he even asked about the midwife thing the first time around and he was actually more into it than I was, he was thinking that we maybe wanted a doula the first time around as well because his sister had a doula and said it helped a lot. (Carla)

In contrast, one woman made plans without her partner’s input:

In my ideal world, my husband would have been more involved in planning, he would have had more of an interest in it, but he didn’t, he doesn’t, and I’m used to that in our relationship. . . . It was mostly me and I knew what I wanted and I had a clear sense that this was my birth, and if my husband had wanted to be more involved, then certainly I would have been open to that, but he didn’t and so it was essentially my birth and it was going to happen the way I wanted it. (Marlene)

Care providers also influenced women’s birthing decisions by providing information or supporting a woman’s preexisting philosophy of childbirth. Women in this study viewed care providers not only as sources of information, but also as sources of experienced knowledge in making informed decisions. One participant recalled the following discussion with her midwife:

We talked about pain management and different options, that kind of thing. We talked about the actual delivery and she pulled out, like, you know the pelvis bones in a little bag and showed me how it all would happen and, um, she just always answered questions I had. (Tessa)

For two women, the philosophy held by a care provider was important. Lara noted that she and her midwife shared a similar philosophy of childbirth and that this helped her in making birth-related decisions. Lara explained, “I think that it helped that the midwives have a similar philosophy that I do. . . . I think that a lot of who you are using, having the same philosophy helps.” Another participant felt similarly: “I went to meet with the midwife and really connected well with her, really liked her philosophies on birthing being a very natural process and I really like the time that midwives spend with their clients” (Joni). Care providers’ knowledge, whether based on experience or a philosophical basis, influenced women’s planning and what happened when, during the birth, changes were made to the initial plan.

Changes to the Birth Plan

In comparing initial plans to actual birth experiences, we observed varying levels of specificity in participants’ initial birth plans. Examples of low level of specificity are illustrated in the following comments from participants:

I pretty much had my mental idea in my head. That was, I wasn’t very picky, like, I wanted [the baby] delivered and safe and didn’t want an epidural. (Katrina).

I knew I wanted to do it in the hospital and I wanted to try without an epidural and other than that I was like, whatever happens, happens and just, I’ll keep an open mind so that the birth can be healthy. (Melody)

[The] birth plan for us was, I think, intentionally vague with a lot of holes in it . . . at the end of the experience I wanted to be as healthy as I could possibly be and I wanted to have a healthy baby. (Lara)

These three women recognized that they could not predict how their birth would unfold. Other participants had highly specified birth plans concerning their care providers, place of birth, and medical intervention, as reflected in the following comments:

I wanted as little intervention as possible and that was throughout the whole pregnancy, so that was probably at the top of the list, which really informed the rest of it. (Marlene)

I’ve worked in health-care community services for a number of years, so I was pretty determined that I wanted it to be as nonmedical as possible, so my intention in the very beginning was to have a natural childbirth with no pain medication whatsoever. (Thelma)

The level of specificity, to a large extent, determined the amount of flexibility women had in terms of changes to their birth plan.

Drastic changes to a woman’s birth plan that allowed little or no control for the women were the most devastating. Three factors caused significant changes to occur in the women’s birth plans: (a) the individual who attended the birth (midwife vs. obstetrician) and where the birth took place (home vs. hospital); (b) the type of pain control and amount of medical intervention used; and (c) the length of hospital stay and the adequacy of care.

Transfers of care and its impact on women’s experiences.

In total, 87% (13 of 15 women) of participants initially planned to have a midwife as their primary care provider. Of these, 16% (six women) had their care transferred to an obstetrician at some point during pregnancy, labor, or postpartum. In addition, three participants who planned to give birth at home were transferred to the hospital at some point during their labor. Both of these types of changes to the initial birth plan impacted the women’s views of their birth experience. As reflected in the following comments, some participants recalled positive experiences:

I got good care from everyone at the hospital, especially at the birth . . . even though it wasn’t my ideal situation like home, I cannot complain about the care. (Regina)

[I felt] so supported by the hospital. The nurses were awesome, like I could have gotten a crummy nurse and I got a nurse who was completely into that . . . and helped me nurse him. (Marcy)

The nurses on the floor were amazing, like you would push the button and they would be there in a second because there’s only so much my husband could do and feel comfortable doing. (Selah)

Several participants also had negative experiences with transferring care and/or transferring from birthing at home to the hospital, particularly for those who transferred from a midwife to an obstetrician.

When I was readmitted for my blood clot, because I was officially under care of an obstetrician, they, the midwives, weren’t given access to see what my blood tests were and things that they would get in a normal case. (Regina)

It was scary and sad. . . . I was just starting to have this relationship with her [midwife] . . . it was all so fast. . . . I was having twins and it was just all crazy. . . . I’m losing the woman who was going to protect me. (Selah)

For these participants, having a change in care provider during pregnancy or birth was frustrating and disappointing. Three participants discussed giving birth in the hospital after planning for a home birth:

Just being there, I hated it and so I just, I had a bad attitude about the whole thing right from the moment we had to leave this house. . . . I couldn’t control it, it was like this visceral response, like I just was not comfortable there. (Joni)

I had monitors now strapped on to me and I was limited to only lying on my back and I couldn’t be in any other position. . . . It was all of a sudden a three-ring circus . . . we no longer seemed the focus and we were not. I was not talked to really, it was just, “Let’s read the machines . . . ” it really felt that way. (Regina)

I have the experience of having a baby in the way that I know what my rights are and I know that if I go to a hospital I don’t have to do everything that they tell me I have to do, and that irritates me that other women don’t know . . . what their choices are. (Paige)

Changes to a birth plan impacted overall birth experiences. Some of the participants reported positive effects; however, if the change was drastic, the experience was negative.

Pain control plan and medical intervention.

Approaches for pain management and general medical intervention varied greatly. Some participants desired to keep their plan open, whereas other participants were adamantly opposed to medical pain management. Circumstances for changes in pain management and medical intervention emerged in three themes that are not discrete: (a) from without pain management medication to having some form of pain medication; (b) from home birth to a hospital birth (one participant); and (c) from a vaginal hospital birth with a midwife to cesarean surgery (one participant). The following statements are these particpants’ descriptions of their experiences in shifts in pain management:

I wanted to have a drugless birth and . . . I did not want to give birth on my back. The first thing they did when I got into the hospital was put me on my back and I looked at the surgeon and was like . . . I don’t know how people sit like this, it was the most pain I had been in the entire time and I was like I can’t handle this and she’s like, “That’s why we’re giving you drugs,” and I was like, “No, just let me stand up!” (Tessa)

I felt like I almost gave up at that point and I just said, “I can’t, I need to have some medication.” I really didn’t want to beforehand, but at that moment it was like I needed it . . . it was all I could do to wait until that person came in to do the epidural. (Joni)

I still wanted to have a vaginal birth, natural if I could. Going through my prenatal classes I found out that at [the hospital], they actually don’t allow you to have a natural childbirth with multiples, it’s pretty much mandatory you have to have an epidural right from the beginning of labor. (Selah)

It was just enough to kind of make me feel off . . . had someone said to me before, like, “Nubain’s not available anymore, these are your options” . . . before I was right in the thick of things, I think it would have just affected me differently. (Jenna)

For two women, although the decision to have an epidural was not part of their initial birth plan, they expressed control over making this change.

I think, like with the epidural, where I really didn’t want it, the way it was presented at least wasn’t . . . I guess I didn’t feel like I had given up on not having it because of the way it was presented. (Katrina)

This is one of those things that’s control and choice. If you get too stuck on something, you feel guilty afterwards. (Marcy)

A second theme in pain management is seen in the experiences of women who planned to give birth naturally and had to have their labor induced, which led to the use of epidurals and other medical pain management. Joni experienced a great loss of control.

I really wanted to give it more time to see if labor would come, still holding on to my home birth idea . . . then the midwife said, “It’s now 24 hours so we’ve gotta head to the hospital,” so she was born in the hospital by induction as opposed to a more natural childbirth . . . so our plans changed a lot . . . I think emotionally, too, I just felt like this is so not happening the way it’s supposed to be happening and there’s this pressure for this to happen fast and making it happen fast that it is so unbearably painful, like, I just, if this is how it’s going to happen then I need some relief because I can’t go on like this. (Joni)

Finally, the third theme in pain management reflected one participant who initially planned for a natural birth with a midwife and was transferred to an obstetrician because she was pregnant with twins. Upon discovering that her babies were not in the correct position for a vaginal birth, Selah was informed that she would need to have cesarean surgery. For her, finding out that her planned method of giving birth was not a possibility had a severe impact on her decision and left her feeling “defeated.” She said, “I just felt defeated, like I have no choices now, like none. I don’t have any choice in my birthing, nothing, these babies are coming and I have to have an operation. I have to have stomach surgery.” Generally, participants who experienced a great deal of change to their birth plan in terms of pain management and medical intervention had a difficult time dealing with these changes and, overall, had a more negative view of the birth.

Stays in hospital. Many women (87%, n = 13) had some experience with staying in the hospital for a period of time after the birth of their child. Of these, 31% (n = 4) had planned a home birth. Three of these women (23%, n = 3) transferred to the hospital while birthing, and one participant’s child was transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit shortly after being born at home. Women who had not initially planned on being admitted to and staying in the hospital said the experience was not positive, as reflected in the following statements:

It was definitely a very different experience and it wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted to be home and just skin-on-skin with my baby and that’s not what I had. . . . I just pretty much kept my mouth shut because I knew that I had a very clear sense that the nurses were not very supportive of anyone who had had a home birth. (Marlene)

I was in a lot of pain and they wouldn’t allow [the baby] to stay with me unless I didn’t take any pain killers, so it really felt like people were going against me in a weird way because . . . after a c-section, you get a ton of pain killers, but your baby still stays with you, right? (Regina)

I didn’t even, at that point, really get a chance to bond with them [the twins] because I was so sick. I didn’t want anything to do with them. . . . I still felt really horrible and then the lactation nurse was coming in and harassing me and trying so hard to force my kids on me. (Selah)

The main factor that all of these participants had in common was the drastic change in their birth plans. For them, it was not necessarily simply a transfer to the hospital that led to negative experiences, but rather an extended stay in the hospital. Negative experiences were related to the degree of change and amount of control over the changes.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study show that women rely on the expertise of trusted care providers, such as midwives and obstetricians, in order to make birth-related decisions during the planning phase. The findings also suggest that the existence of a birth plan, although helpful, was not essential for participants. Women who had a flexible birth plan felt that they had more room for negotiation during labor and birth. The Wittmann-Price (2004, 2006) model of women’s health decision making suggests that women seek personal knowledge about their birth choices and that one of the avenues for this information is the woman’s care provider(s). This model also emphasizes the importance of a flexible environment. In this study, women who needed to renegotiate their birth plan while in labor benefitted from a flexible environment. Women who felt a loss of control during the birth process were not well supported in renegotiating their birth plan due in part to structured health-care protocol that was not in the woman’s control.

Previous research has suggested that when changes to a woman’s birth plan are necessary, it is the amount of control that the woman maintains over these changes that is important to sustaining a positive birth experience (Hardin & Buckner, 2004; Hauck et al., 2007). In the current study, two key factors were related to the impact of changes to the birth plan on the women’s childbirth experiences: (a) the degree of change that took place and (b) the amount of control the birthing woman had over the changes as they occured.

The most drastic changes to women’s birth plans include transfers of care from home to hospital and/or from midwife to obstetrician, the use of medical pain control techniques and other medical interventions, and unexpected stays in the hospital after the birth of the child. Women who experience all of these changes and who have little to no control over the decision-making process as changes are happening tend to use negative adjectives when describing their overall birth experience; for example, “defeated,” “frustrated,” and “traumatizing.” When women experience a smaller degree of change and maintain some level of control over the decision making around these changes to their plan, the changes do not have a negative impact on their overall birth experience. This is connected to positive reflections on the overall birth experiences, including words like “fantastic,” “empowering,” and “supported.” From this, we can conclude that it is not simply the fact that the birth plan changed that leads to positive or negative feelings, it is the degree to which the initial plan is modified and, importantly, the degree of control that women have over the changes as they are happening.

When women are well supported in making decisions and have a great deal of trust in their care providers to make decisions on their behalf, women have a more positive recollection of their birth experiences. This finding of a connection between control over birth plan changes and overall view of the birth process is consistent with the findings of a previous study that concluded that control over the physical, emotional, and mental aspects of childbirth are important to women (Hardin & Buckner, 2004). When women’s care transfers from a midwife to an obstetrician, they tend to consult with their midwives before making birth-related decisions. Women who were supported by this type of consultation did not experience a severe loss of control. Women who do not have an opportunity to consult with their midwives on changes to their birth plan, or women whose midwives are no longer in control of the changes, experience a greater loss of control and, therefore, describe a more negative overall experience.

Women who had a flexible birth plan felt that they had more room for negotiation during labor and birth.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is the nature of the sample. The sample comprised 15 self-selected women who contacted us. Consequently, the diversity (e.g., ethnic, racial, sexual orientation, socioeconomic) of Waterloo Region was not proportionately represented in the sample. Additionally, the sample of this study did not equally represent the various ways in which women choose to give birth, including a variety of care providers and places of birth. Specifically, only one participant chose an obstetrician as her primary care provider from the beginning of her pregnancy, and only one participant chose a general practitioner as her primary care provider. Although several women had their care transferred from a midwife to an obstetrician, this situation represents a very different set of choices and circumstances than those of women who chose to work with an obstetrician from the beginning of their pregnancy.

Finally, this study is very specific to the Waterloo Region in Ontario, Canada, and the options that are offered to women in this area. The support and information available to women varies depending on location. The specific context in which this study was conducted must be considered when determining the transferability of these findings to other contexts.

Implications and Conclusions

The current study provides a snapshot of childbirth experiences in Waterloo Region, Ontario, Canada, during the end of 2009 and the beginning of 2010. The findings from this study have the potential to impact the level and type of care that is offered to women in this region of Ontario. It is clear from this study that the particular type of care a woman chooses is not necessarily the most important concept related to her ability to maintain control over the birth process. In this study, women’s positive and negative recollections of their birth experience were more related to experiences of choice and control than they were to the individuals who were present in the birthing room or the particular interventions that were chosen or necessary during a woman’s birth experience.

Recommendations for Health-Care Professionals and Birthing Women

The clearest recommendation that results from this study is that all members of the labor and birthing care team, including family, partners, nurses, doulas, midwives, and obstetricians, need to support women in making informed choices and negotiating these decisions during the birth process. This can be accomplished through consultation and information sharing that begins during pregnancy and continues through the postpartum period. It is important for the birthing woman to remain at the center of her birth experience and to be well supported in making necessary decisions. Additional research is needed to better understand the ways in which care providers incorporate these concepts into their practices.

The type of care that women in the current study received from midwives tended to incorporate the concepts of informed choice, flexibility, and support. This finding suggests that an increased availability in midwifery care is an important approach to ensuring that women have not only a healthy birth experience but also one that is positive. Additionally, although midwifery care is covered under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, this is not the case in other provinces (e.g., Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland). A first step in providing a choice over type of care provider to a wider number of women is to make midwifery care free and accessible for all women in Canada.

On its website, The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) states the following in describing the organization’s beliefs:

Women should have equitable access to optimal, comprehensive health care . . . women should have the information they need to make choices about their health . . . the Society has a responsibility to facilitate change in relation to health system issues affecting the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. (SOGC, 2008, para. 1)

This statement by the SOGC suggests that the society’s goals for practitioners are consistent with the recommendations of this study. Future research with practitioners could shed light on ways in which individual practitioners implement these values. Incorporating the stated mission of the SOGC into obstetrical education is also an important step in ensuring that all practitioners carry out these beliefs.

Furthermore, the Public Health Agency of Canada (2000) publication “Family-Centered Maternity and Newborn Care: National Guidelines” is meant for all care providers, including midwives and obstetricians. These guidelines incorporate informed choice in a woman-centered model of care that focuses on the physical, psychological, and social needs of the woman and her baby. The findings of our study suggest that these guidelines need to be further incorporated into obstetric practice and education.

This study provides a stepping stone for future research studies aimed at better understanding the role of choice and control in women’s childbirth experiences. In addition, this study gives service providers a framework on which to base the service that they provide to pregnant and birthing women. Finally, this study provides relevant and useful information for expectant parents in choosing the type of care they access during pregnancy, labor, birth, and the postpartum period.

Biography

KATIE COOK is a community psychologist and independent researcher in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. COLLEEN LOOMIS is an associate professor of psychology at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

REFERENCES

- Berg M., Lundgren I., Lindmark G. (2003). Childbirth experience in women at high risk: Is it improved by use of a birth plan? The Journal of Perinatal Education, 12(2), 1–15 10.1624/105812403X106784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton T., Callister L. C., Stoneman E. (2005). Decision making in laboring women: Ethical issues for perinatal nurses. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 19(2), 145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M. E. (2010). Midwifery care: Reflections of midwifery clients. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 19(4), 41–51 10.1624/105812410X530929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox B., Worts D. (1999). Revisiting the critique of medicalized childbirth: A contribution to the sociology of birth. Gender & Society, 13, 326–346 10.1177/089124399013003004 [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins J., Thomson A. M. (2001). Women’s expectations and experiences of childbirth. Midwifery, 17(4), 302–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin A. M., Buckner E. B. (2004). Characteristics of a positive experience for women who have unmedicated childbirth. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 13(4), 10–16 10.1624/105812404X6180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck Y., Fenwick J., Downie J., Butt J. (2007). The influence of childbirth expectations of Western Australian women’s perceptions of their birth experience. Midwifery, 23(3), 235–247 10.1016/j.midw.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell-White S. (1997). Choosing a birth attendant: The influence of a woman’s childbirth definition. Social Science & Medicine, 45(6), 925–936 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. C., Liston R., Fraser W. D., Baradaran N., Hearps S. J., Tomkinson J., Maternity Care Research Group (2011). Attitudes of the new generation of Canadian obstetricians: How do they differ from their predecessors? Birth, 38(2), 129–139 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach A. C., Becker J., Worley H. (2004). The impact of community health workers on the self-determination, self-sufficiency, and decision-making ability of low-income women and mothers of young children. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 343–356 10.1002/jcop.20006 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S. C., Lin K. C., Hsu C. H., Yang C. C., Chang M. Y., Tsao C. M., Lin L. C. (2010). Evaluation of the effects of a birth plan on Taiwanese women’s childbirth experiences, control and expectations fulfillment: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(7), 806–814 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren I., Berg M., Lindmark G. (2003). Is the childbirth experience improved by a birth plan? Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 48(5), 322–328 10.1016/S1526-9523(03)00278-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea B. H., Wright M. (1999). Satisfaction in childbirth and perceptions of personal control in pain relief during labour. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(4), 877–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noone J. (2002). Concept analysis of decision making. Nursing Forum, 37(3), 21–32 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2002.tb01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell A., Salo-Coombs V., Herring A., Spielman F., Fecho K. (2011). Anesthesia and analgesia-related preferences and outcomes of women who have birth plans. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 56(4), 376–381 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2000). Family-centered maternity and newborn care: National guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-ps/dca-dea/publications/fcm-smp/index-eng.php

- Society of Obstetricans and Gynaecologists of Canada (2008, . October 17). About SOGC: Mission/history. Retrieved from http://sogc.org/about/about_e.asp

- Waldenström U., Hildingsson I., Rubertsson C., Rådestad I. (2004). A negative birth experience: Prevalence and risk factors in a national sample. Birth, 31(1), 17–27 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.0270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann-Price R. A. (2004). Emancipation in decision-making in women’s health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(4), 437–445 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann-Price R. A. (2006). Exploring the subconcepts of the Wittman-Price theory of emancipated decision-making in women’s health care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 38(4), 377–382 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2005). World health report 2005: Make every mother and child count. Geneva, Switzerland: Author [Google Scholar]