Abstract

We conducted a study comparing the OraQuickADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test, Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV Test, Determine HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo, EIA, and pooled nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). Men who have sex with men rated tests based on specimen collection method and trust in each test. Among 490 subjects, OraQuick performed on oral fluids ranked highest for specimen collection method but lowest on trust; NAAT scored highest on trust. Among a subset of these subjects, 46% would opt for NAAT if choosing one test. Strategies are needed to increase HIV testing that is accurate and consistent with client preferences.

Keywords: HIV testing, rapid HIV test, patient preference

Introduction

Recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention promote routine HIV antibody screening and more frequent targeted testing among high risk populations [1]. Unfortunately, strategies limited to antibody detection cannot identify highly infectious persons with acute HIV infection [2, 3]. These missed diagnoses represent lost opportunities to link persons into care and reduce the contribution recently-infected persons make to ongoing transmission [4–11]. In response, some public health programs began pooled nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) [12–16], increasing costs, laboratory complexity, and turnaround time for test results.

Conversely, point-of-care (POC) HIV tests trade off rapid turnaround times and ability to provide results to more persons [17, 18] in exchange for a low sensitivity during the “window period” comparable to earliest generations of enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) [19–22]. In Seattle, the OraQuickADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraQuick, OraSure Technologies Inc.) detected only 91% of antibody-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) with established infection and 80% of MSM with acute or established HIV infection [12, 23]. It is uncertain whether other POC tests perform substantially differently, as studies using these tests on frozen specimens from persons with early infection have conflicting results [12, 22, 24, 25].

In 2010, we began a prospective, cross-sectional study to compare the ability of different HIV tests to detect early infection in Seattle MSM, a population with high incidence and frequent testing. Previous studies suggest persons might prefer POC testing over venipuncture and laboratory-based testing [18, 26, 27] and oral fluid over fingerstick specimen collection [18, 28]. We surveyed subjects to determine preferences in this population and evaluate the relative importance of specimen collection method (oral fluid, fingerstick, or venipuncture), turnaround time, and perceived test accuracy.

Methods

Population

MSM and transgender persons were recruited into the main study at the Public Health - Seattle & King County STD Clinic, Gay City Health Project Wellness Center (community-based organization), and University of Washington Primary Infection Clinic (research clinic). Persons were eligible if they were HIV-negative, reported sex with a man in the preceding year, could read and write in English, and had not participated in the study within three months. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all subjects gave verbal consent.

HIV Testing

Study procedures included one POC test performed on oral fluids (OraQuick) and two or three POC tests performed on fingerstick whole blood specimens: OraQuick (5μL), Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV Test (Uni-Gold, Trinity Biotech, 50μL), and Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Determine, Alere Inc., 50μL). Determine is not currently Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved and not available for sale in the United States; devices were provided by the manufacturer for investigational use ten months after study enrollment began. We selected these tests because OraQuick is the predominant POC test used in Seattle, Uni-Gold’s technology might make it more sensitive during early infection [29, 30], and Determine is an antigen-antibody combination assay that can detect p24 antigen and incorporates principles of 3rd generation EIAs for antibody detection. POC tests were performed on specimens collected from separate fingersticks to obtain recommended specimen volumes, perform each test as directed, and ensure study validity.

Study counselors provided all POC test results. Serum specimens from subjects with negative POC results were sent for EIA and pooled NAAT as previously described [12] with the following changes: we used the Genetic Systems HIV-1/HIV-2 Plus O EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and EIA-negative specimens were combined into 27-specimen pools using a 3x3x3 matrix [31] for testing with the Abbott RealTime HIV-1 RNA assay (Abbott Molecular Inc). Subjects with reactive fingerstick test results had serum sent for confirmatory testing, CD4+ T-cell count, and HIV RNA level; and an appointment was scheduled to provide results, partner services, and linkage to care. Subjects received $20 for participation in the main study, which is ongoing.

Survey

The first 1000 subjects enrolled at the Public Health STD Clinic and Gay City Wellness Center were asked to complete an anonymous, self-administered written survey that was not linked to clinic records. During study recruitment and testing, subjects were informed about technologies and test characteristics, including estimated window periods [32]. Because the primary objective of the main study is to compare window periods of POC tests, subjects were told that antibodies become detectable approximately one month after HIV acquisition but it may take up to three months before POC tests can detect antibodies. Subjects were told that p24 antigen is present by the time of peak viremia and symptom onset (approximately two weeks after acquisition) but it is not known when Determine could detect antigen.

Following completion of POC testing and post-test counseling, HIV-negative subjects were asked individually to rate tests on a scale of 1 to 5 based on their preference for the specimen collection method. They then gave each test a single score for trust (from 1 to 5) based on their personal weighting of previously-described test characteristics (e.g. specimen collection method, amount of specimen required, processing time, POC versus laboratory-based testing, and expected window period) and the timing of their visit relative to recent risk. The protocol did not specify additional information to be provided at this time. Finally, subjects were asked to select the one test they would choose, taking all factors into account, if they could have only one HIV test that day.

Results

Between February 22, 2010 and July 31, 2011, 1000 subjects were enrolled. Forty-two (4.2%) subjects were newly diagnosed with HIV infection. Thirty-two (3.2%) HIV-infected subjects had concordantly reactive POC test results, and three (0.3%) HIV-infected subjects had at least one reactive and one non-reactive test result. One (0.1%) subject had non-reactive results on all POC tests (including Determine) but a reactive EIA. Six (0.6%) subjects were acutely infected (EIA-negative/NAAT-positive); the one subject tested after Determine was incorporated into study procedures had a reactive p24 antigen result.

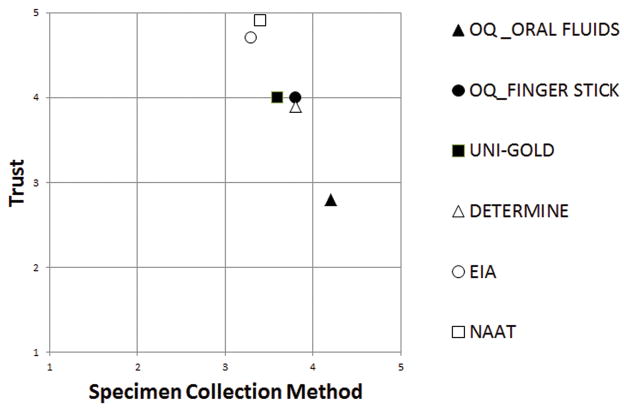

Of 958 HIV-negative subjects, 490 (51%) completed the survey. Mean scores for preference for specimen collection methods (Figure) were: OraQuick (oral fluids) 4.2, OraQuick (fingerstick) 3.8, Uni-Gold (fingerstick) 3.6, Determine (fingerstick) 3.8, EIA (venipuncture) 3.3, and NAAT (venipuncture) 3.4. Mean scores for trust were: OraQuick (oral fluids) 2.8, OraQuick (fingerstick) 4.0, Uni-Gold 4.0, Determine 3.9, EIA 4.7, and NAAT 4.9.

Figure. Preference for specimen collection methods and trust in HIV tests are inversely related.

Subjects rated six study HIV tests on a scale from 1 to 5 based on preferences for the specimen collection method (x axis) and trust in that test based the timing of their visit relative to recent risks for HIV acquisition (y axis). Among 490 subjects, testing on oral fluids (▲) had the highest mean rating for specimen collection method (4.2), but OraQuick performed on oral fluids was the least trusted test (2.8). In contrast, venipuncture (○□) had the lowest scores among the specimen collection methods but pooled HIV NAAT was the most trusted test (4.9) The three rapid rests performed on fingerstick specimens were rated similarly on both scores.

Among subjects surveyed before study procedures included Determine, 128 (49%, 95% CI 42–55%) of 263 subjects chose NAAT as the one test they would select, 49 (19%) chose OraQuick (fingerstick), 38 (14%) chose Uni-Gold, 29 (11%) chose EIA, and 19 (7%) chose OraQuick (oral fluids). Among 120 subjects surveyed after inclusion of Determine, 55 (46%, 95% CI 37–55%) chose NAAT, 18 (15%) chose Uni-Gold, 11 (9%) chose OraQuick (fingerstick), nine (8%) chose EIA, and eight (7%) chose OraQuick (oral fluids). Determine was selected by 19 (16%) subjects, and others voiced doubts because this test is not yet FDA-approved.

Discussion

As in other studies, MSM we surveyed preferred less invasive collection methods. However, they expressed greater trust in test results from fingerstick whole blood and venipuncture specimens. Other factors, including concerns about the window period, were apparently more important than preferences for collection method and immediacy of test results, because nearly half of subjects opted for venipuncture and NAAT when asked to choose one test.

Our study has several limitations, including the fact that information provided could have influenced responses, and conversations during pre-test counseling likely varied by client. Due to our selection bias, these findings may only be applicable to persons who have previously tested, as persons who have never tested often express preferences for oral fluid testing [26]. Our results might also not apply to populations with less knowledge about tests or low-incidence settings where testing during early infection is infrequent. However, we believe these results are relevant for MSM in cities similar to Seattle. Over 90% of Seattle MSM have previously tested [33], and knowledge of pooled NAAT is high [unpublished data]. Our findings suggest that programs for MSM should offer combination testing, e.g. POC testing plus pooled NAAT, to accomplish goals of client acceptance and early detection. Strategies in other settings might vary depending on whether programs aim to increase testing frequency [34, 35] (requiring tests able to detect recent infection) or lower barriers among untested populations (favoring less invasive methods).

Antigen-antibody combination assays (4th generation immunoassays) can detect acute HIV infection, have shorter turnaround times compared to NAAT, and will likely affect how we contemplate these trade-offs [12, 34]. Two laboratory-based 4th generation assays are approved for use in the United States. If POC 4th generation assays prove to be accurate in populations such as ours and obtain FDA-approval, preferences could change.

As public health programs expand testing as part of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, we must increase access to tests that are not only highly sensitive and specific, but also account for client preferences. Validating measurements to assess these preferences deserves further attention through study of patient-centered outcomes. In high HIV incidence populations like ours, currently approved POC tests are inadequate, failing to detect 20% of HIV-infected persons in our studies, and must be supplemented with pooled NAAT or 4th generation assays [12, 36, 37] that are cost-effective when targeted [38]. More importantly, we cannot miss opportunities to diagnose these 20%, the most-infectious persons, who have already walked through our doors for testing. Thankfully, our clients agree: the best tests are worth the wait.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the study participants and the study counselors at the Gay City Health Project Wellness Center. We would also like to thank Heather Baldwin, MPH for database management and other assistance.

Sources of support: NIH R01 MH-83630. Alere provided Determine™ HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo tests and controls for investigational use. This test is not available for sale in the United States.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the 2011 National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA; August 14-17, 2011 [abstract #1595].

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, Garrett PE, Schumacher RT, Peddada L, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. Aids. 2003;17:1871–1879. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. Aids. 2006;20:1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollingsworth TD, Anderson RM, Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:687–693. doi: 10.1086/590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yerly S, Vora S, Rizzardi P, Chave JP, Vernazza PL, Flepp M, et al. Acute HIV infection: impact on the spread of HIV and transmission of drug resistance. Aids. 2001;15:2287–2292. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111230-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pao D, Fisher M, Hue S, Dean G, Murphy G, Cane PA, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 during primary infection: relationship to sexual risk and sexually transmitted infections. Aids. 2005;19:85–90. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JP, Moisi D, Ntemgwa M, Matte C, et al. High Rates of Forward Transmission Events after Acute/Early HIV-1 Infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:951–959. doi: 10.1086/512088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquez JA, Koopman JS, Simon CP, Longini IM., Jr Role of the primary infection in epidemics of HIV infection in gay cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1169–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koopman JS, Jacquez JA, Welch GW, Simon CP, Foxman B, Pollock SM, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:249–258. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199703010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiridou M, Geskus R, de Wit J, Coutinho R, Kretzschmar M. Primary HIV infection as source of HIV transmission within steady and casual partnerships among homosexual men. Aids. 2004;18:1311–1320. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:444–453. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facente SN, Pilcher CD, Hartogensis WE, Klausner JD, Philip SS, Louie B, et al. Performance of risk-based criteria for targeting acute HIV screening in San Francisco. Plos One. 2011;6:e21813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Priddy FH, Pilcher CD, Moore RH, Tambe P, Park MN, Fiscus SA, et al. Detection of Acute HIV Infections in an Urban HIV Counseling and Testing Population in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000254323.86897.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel P, Klausner JD, Bacon OM, Liska S, Taylor M, Gonzalez A, et al. Detection of acute HIV infections in high-risk patients in California. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:75–79. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218363.21088.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson AB, Branson BM, Kim A, Farnham PG. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of alternative HIV counseling and testing methods to increase knowledge of HIV status. Aids. 2006;20:1597–1604. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238405.93249.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberg F, Branson BM, Goldbaum GM, Lockhart D, Kurth A, Rossini A, et al. Choosing HIV Counseling and Testing Strategies for Outreach Settings: A Randomized Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:348–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuun E, Brashaw M, Heyns AD. Sensitivity and specificity of standard and rapid HIV-antibody tests evaluated by seroconversion and non-seroconversion low-titre panels. Vox Sang. 1997;72:11–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1997.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samdal HH, Gutigard BG, Labay D, Wiik SI, Skaug K, Skar AG. Comparison of the sensitivity of four rapid assays for the detection of antibodies to HIV-1/HIV-2 during seroconversion. Clin Diagn Virol. 1996;7:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0197(96)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beelaert G, Vercauteren G, Fransen K, Mangelschots M, De Rooy M, Garcia-Ribas S, et al. Comparative evaluation of eight commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent assays and 14 simple assays for detection of antibodies to HIV. J Virol Methods. 2002;105:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen SM, Yang C, Spira T, Ou CY, Pau CP, Parekh BS, et al. Alternative algorithms for human immunodeficiency virus infection diagnosis using tests that are licensed in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1588–1595. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02196-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stekler J, Wood RW, Swenson PD, Golden M. Negative rapid HIV antibody testing during early HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:147–148. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louie B, Wong E, Klausner JD, Liska S, Hecht F, Dowling T, et al. Assessment of rapid test performances for HIV antibody detection in recently infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01945-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masciotra S, McDougal J, Feldman J, Sprinkle P, Wesolowski L, Owen S. Evaluation of an alternative HIV diagnostic algorithm using specimens from seroconversion panels and persons with established HIV infections. J Clin Virol. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.09.011. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen MY, Bilardi JE, Lee D, Cummings R, Bush M, Fairley CK. Australian men who have sex with men prefer rapid oral HIV testing over conventional blood testing for HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:428–430. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.009552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spielberg F, Branson BM, Goldbaum GM, Lockhart D, Kurth A, Celum CL, et al. Overcoming barriers to HIV testing: preferences for new strategies among clients of a needle exchange, a sexually transmitted disease clinic, and sex venues for men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:318–327. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200303010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaydos CA, Hsieh YH, Harvey L, Burah A, Won H, Jett-Goheen M, et al. Will patients “opt in” to perform their own rapid HIV test in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ketema F, Zink HL, Kreisel KM, Croxton T, Constantine NT. A 10-minute, US Food and Drug Administration-approved HIV test. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2005;5:135–143. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louie B, Wong E, Klausner JD, Liska S, Hecht F, Dowling T, et al. Assessment of rapid tests for detection of human immunodeficiency virus-specific antibodies in recently infected individuals. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2008;46:1494–1497. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01945-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldsmith J. High Throughput Donor Plasma NAT Screening Assay Applied to Acute HIV Detection in a Public Health Setting. 2007 HIV Diagnostics Conference; Atlanta, GA. December 5–7, 2007; [oral #3]; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stekler J, Maenza J, Stevens CE, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Wood RW, et al. Screening for acute HIV infection: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:459–461. doi: 10.1086/510747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer DD, Golden MR, Handsfield HH. Unsafe sexual behavior and correlates of risk in a probability sample of men who have sex with men in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:250–255. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194595.90487.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helms DJ, Weinstock HS, Mahle KC, Bernstein KT, Furness BW, Kent CK, et al. HIV testing frequency among men who have sex with men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics: implications for HIV prevention and surveillance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:320–326. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HIV testing among men who have sex with men--21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:694–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandori MW, Hackett J, Jr, Louie B, Vallari A, Dowling T, Liska S, et al. Assessment of the ability of a fourth-generation immunoassay for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody and p24 antigen to detect both acute and recent HIV infections in a high-risk setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2639–2642. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00119-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel P, Mackellar D, Simmons P, Uniyal A, Gallagher K, Bennett B, et al. Detecting acute human immunodeficiency virus infection using 3 different screening immunoassays and nucleic acid amplification testing for human immunodeficiency virus RNA, 2006–2008. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:66–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchinson AB, Patel P, Sansom SL, Farnham PG, Sullivan TJ, Bennett B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pooled nucleic acid amplification testing for acute HIV infection after third-generation HIV antibody screening and rapid testing in the United States: a comparison of three public health settings. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]