Abstract

Aims: In this study we identified viral gene targets of the important redox regulator thioredoxin (Trx), and explored in depth how Trx interacts with the immediate early gene #1 (IE1) of the white spot syndrome virus (WSSV). Results: In a pull-down assay, we found that recombinant Trx bound to IE1 under oxidizing conditions, and a coimmunoprecipitation assay showed that Trx bound to WSSV IE1 when the transfected cells were subjected to oxidative stress. A pull-down assay with Trx mutants showed that no IE1 binding occurred when cysteine 62 was replaced by serine. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1 was downregulated under oxidative conditions, and that Penaeus monodon Trx (PmTrx) restored the DNA binding activity of the inactivated, oxidized WSSV IE1. Another EMSA experiment showed that IE1's Cys-X-X-Cys motif and cysteine residue 55 were necessary for DNA binding. Measurement of the ratio of reduced glutathione to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) in WSSV-infected shrimp showed that oxidative stress was significantly increased at 48 h postinfection. The biological significance of Trx was also demonstrated in a double-strand RNA Trx knockdown experiment where suppression of shrimp Trx led to significant decreases in mortality and viral copy numbers. Innovation and Conclusion: WSSV's pathogenicity is enhanced by the virus' use of host Trx to rescue the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1 under oxidizing conditions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 914–926.

Introduction

Thioredoxin (Trx) is a 12-kDa multi-functional protein that is found ubiquitously in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Trx levels are raised in response to oxidative stress (30), and it is also involved in several cellular responses, including gene expression/regulation, cell proliferation, cellular signaling, and apoptosis (11). Even though it has no nuclear localization signal, Trx can enter the nucleus and modulate the DNA binding activity of several cellular transcription factors (27, 28). Many of Trx's functions depend on its reduction/oxidation (redox) activity. The activity is mediated by a Cys-X-X-Cys motif (14) that allows Trx to reduce the target proteins through its participation in disulfide exchange reactions. A previous study found that Trx was one of the genes that had an increased number of expressed sequence tags in a library derived from postlarvae of Penaeus monodon that were infected with the white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) (16). Trx is often up-regulated after viral infections, but even in humans, the relevance of Trx to viral pathogenesis and the underlying mechanisms of host-viral interaction/regulation are still largely unknown (35). In the present study, to find the candidate WSSV proteins that might interact with Trx, we searched the WSSV genome for open reading frames (ORFs) containing the CXXC motif. This is the same CXXC motif that is found in Trx itself, and it was selected as a search target not only because it can form an intramolecular disulfide bond (thereby providing a mechanism for redox regulation), but also because it allows the formation of an intermediate structure of disulfide exchange between Trx and many of the proteins it regulates (6). Using the GenBank database we identified 70 WSSV ORFs with this motif, 21 of which were annotated (Tables 1 and 2) and 1 of which was WSSV ORF126, the WSSV immediate early gene #1 (IE1). WSSV IE1 is a transcriptional regulator with DNA binding activity and transactivation activity, and its expression is enhanced by STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) (5, 25). However, the mechanisms that regulate WSSV IE1 activity are not yet understood. Since IE1 is a transcription factor with DNA binding activity and Trx is known to regulate DNA binding activity via redox (13, 27, 29), in the present study we investigate the interactions between these two proteins.

Table 1.

Potential Nonstructural Target Proteins of Thioredoxin Based on the Presence of a CXXC Motif in White Spot Syndrome Virus Annotated Open Reading Frames

| WSSV ORF | Protein | Characteristics/function | GenBank number | CXXC motif | Location | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSSV004 | WSSV004 | Early gene | AAL88872.1 | CSAC | 169–172 | (8) |

| WSSV039 | DNA polymerase | DNA replication | AAL88907.1 | CIAC | 342–345 | (4) |

| CLSC | 2346–2349 | |||||

| WSSV108 | WSSV108 | Immediate-early gene | AAL88976.1 | CYTC | 64–67 | (19) |

| CDYC | 155–158 | |||||

| WSSV113 | WSSV113 | Immediate-early gene | AAL88981.1 | CKTC | 190–193 | (20) |

| WSSV126 | IE1 | Immediate-early gene | AAL88994.1 | CNAC | 189–192 | (23–25) |

| WSSV135 | WSSV135 | Immediate-early gene | AAL89003.1 | CASC | 67–70 | (19) |

| WSSV136 | WSSV136 | Immediate-early gene | AAL89004.1 | CPIC | 13–16 | (19) |

| CPMC | 63–66 | |||||

| WSSV150 | WSSV150 | Immediate-early gene | AAL89018.1 | CYYC | 51–54 | (19) |

| CYYC | 56–59 | |||||

| CCYC | 65–68 | |||||

| CYCC | 66–69 | |||||

| CYYC | 69–72 | |||||

| CCCC | 72–75 | |||||

| CYHC | 75–78 | |||||

| WSSV156 | WSSV156 | Immediate-early gene | AAL89024.1 | CNRC | 584–587 | (19) |

| WSSV228 | Ribonucleotide reductase large subunit (RR1) | Nucleotide metabolism | AAL89096.1 | CEMC | 843–846 | (21, 40) |

| WSSV277 | WSSV277 | E3 ligase | AAL89145.1 | CGVC | 308–311 | (9) |

| CPMC | 355–358 | |||||

| WSSV304 | WSSV304 | Immediate-early gene/E3 ligase | AAL89172.1 | CVNC | 310–313 | (46) |

| CEKC | 354–357 | |||||

| WSSV454 | Chimericthymidine kinase and thymidylate kinase (TK-TMK) | Nucleotide metabolism | AAL89322.1 | CMIC | 141–144 | (41–42) |

| CRDC | 178–181 | |||||

| WSSV462 | WSSV462 | Immediate-early gene/E3 ligase | AAL89330.1 | CVGC | 271–274 | (10, 20) |

| CVKC | 309–312 |

WSSV, white spot syndrome virus; ORF, open reading frame.

Table 2.

Potential Structural Target Proteins of Thioredoxin Based on the Presence of a CXXC Motif in White Spot Syndrome Virus Annotated Open Reading Frames

| WSSV ORF | Protein | Characteristics/function | GenBank Number | CXXC motif | Location | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSSV030 | VP362 | Structural protein | AAL88898.1 | CYKC | 70–73 | (48) |

| CPSC | 354–357 | |||||

| CWIC | 379–382 | |||||

| WSSV134 | VP36A | Tegument protein | AAL89002.1 | CNNC | 251–254 | (37, 38) |

| WSSV254 | VP320 | Structural protein | AAL89122.1 | CAIC | 743–746 | (48) |

| CGHC | 761–764 | |||||

| CPSC | 792–795 | |||||

| WSSV315 | VP387 | Structural protein | AAL89183.1 | CDGC | 160–163 | (48) |

| WSSV359 | VP184 | Structural protein | AAL89227.1 | CNAC | 696–699 | (12) |

| CTSC | 715–718 | |||||

| WSSV419 | VP664 | Capsid protein | AAL89287.1 | CQQC | 4104–4107 | (18, 37, 38) |

| WSSV524 | VP136B | Immediate early gene/structural protein | AAL89392.1 | CKGC | 464–467 | (20, 37) |

| CKRC | 865–868 | |||||

| CLRC | 884–887 | |||||

| CVEC | 988–991 | |||||

| CDCC | 991–994 | |||||

| CPWC | 1013–1016 |

Innovation.

We show that thioredoxin (Trx), an important redox regulator, binds to the white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) immediate early gene #1 (IE1) under oxidizing conditions and rescues IE1's DNA binding ability. Trx-IE1 binding is mediated via Trx cysteine 62. IE1's CXXC motif and cysteine 55 are critical for its DNA binding activity. Double-strand RNA knockdown of shrimp Trx leads to reduced mortality and lower virus copy numbers in WSSV-infected shrimp, which suggests that viral pathogenicity is enhanced by WSSV's ability to hijack host Trx.

Our approach was first to use a cDNA microarray and real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm the increased transcription level of Trx in WSSV-infected P. monodon (Supplementary Protocols S1–4; Supplementary Data are available at www.liebertonline.com/ars). Next, we cloned the full-length cDNA sequence of Trx from P. monodon and produced the anti-Trx antibody. Anti-Trx antibody and anti-IE1 antibody were then used in immunoblotting to monitor the in vivo protein expression level of P. monodon Trx (PmTrx) and WSSV IE1 after a challenge with WSSV. A pull-down assay and coimmunoprecipitation were used to investigate whether PmTrx (wild type and various point mutants) could bind to WSSV IE1. EMSA was then used to show that the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1 is regulated by redox, and that Trx could restore the DNA binding activity of the oxidized WSSV IE1. Lastly, various IE1 point mutants were expressed to determine which of several cysteines were critical for IE1's DNA binding activity. To ascertain whether our results were biologically meaningful, we also conducted several in vivo assays. In WSSV-infected shrimp, liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry (LC/ESI/MS) measurement of the GSH/GSSG ratio showed that there was oxidative stress at 48 hours postinfection (hpi). We also found that gene-specific double-strand RNA (dsRNA)–mediated RNA interference was able to silence the expression of shrimp Trx and significantly reduce the cumulative mortality rate and viral copy number in shrimp that were challenged with WSSV.

Results

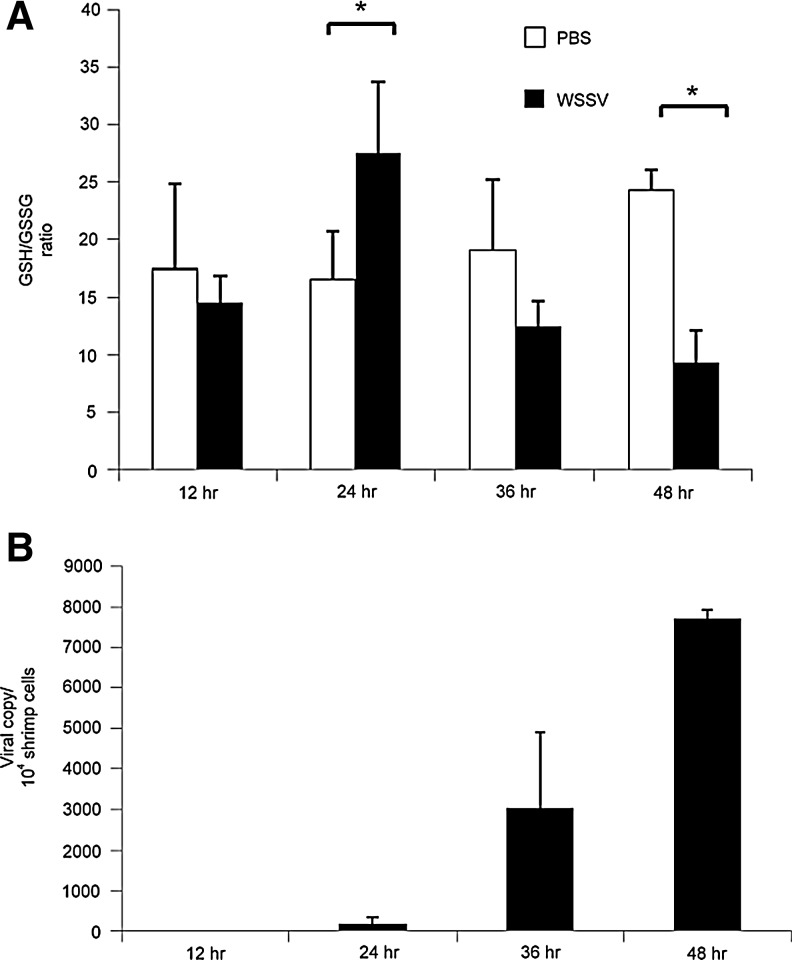

PmTrx and WSSV IE1 protein expression levels after WSSV infection

After confirming that WSSV infection increased the transcription levels of PmTrx (Supplementary Fig. S1) and determining the full length sequence of the PmTrx gene (Supplementary Fig S2; GenBank Acc. No. HQ427879), we used immunoblotting to monitor PmTrx and WSSV IE1 protein levels after WSSV infection.

We found that PmTrx expression was up-regulated at 48 h after WSSV infection (hpi), while expression of the viral protein IE1 was first detected at 24 hpi (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Protein expression levels of PmTrx and WSSV IE1 after WSSV challenge. Immunoblots with anti-Trx antibody or anti-IE1 antibody of total protein (20 μg) extracted from the stomachs of nine individual shrimps. Anti-tubulin antibody was used as the internal control. hpi, number of hours post WSSV challenge; PmTrx, Penaeus monodon thioredoxin; Trx, thioredoxin; WSSV, white spot syndrome virus.

PmTrx binds directly to WSSV IE1 via PmTrx Cys62 (cysteine 62)

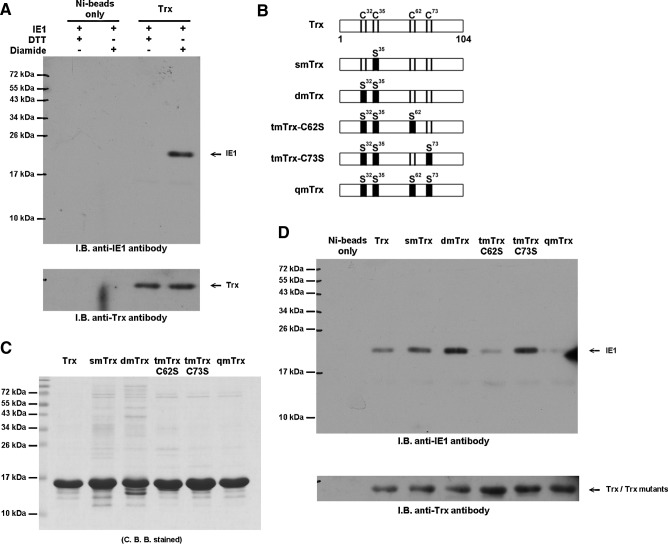

The direct protein–protein interaction between PmTrx and WSSV IE1 was investigated by a pull-down assay in the presence of an oxidizing agent or a reducing agent (diamide and dithiothreitol [DTT]), respectively. Immunoblotting showed that there was only a direct interaction between PmTrx and WSSV IE1 in the presence of the oxidative reagent diamide (Fig. 2A). After confirming the expression of the five PmTrx point mutants used in the assay (Fig. 2B, C), immunoblotting showed that PmTrx cysteine 62 was critical for IE1 binding (Fig. 2D). We conclude that a direct protein–protein interaction occurs between PmTrx and WSSV IE1 in the presence of diamide, a thiol-specific oxidant, and that this interaction is through the cysteine 62 of PmTrx.

FIG. 2.

Pull-down assay of interactions between IE1 and Trx. (A) Purified, His-tag free IE1 (from pGEX5T-1-IE1) (0.5 μg) was mixed with His-tagged Trx (5 μg) in an NPIT buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 0.005% Tween 20, pH 8.0) with 1 mM DTT or 1 mM diamide to a total volume of 200 μl. After 30-min incubation at room temperature, 15 μl nickel agarose beads were added to the mixture to pull down Trx. After five washes with NPIT buffer, bound protein was eluted by a 2× sample buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 2% β-ME, and 0.005% bromophenol blue). Anti-PmTrx antibody was used to confirm that Trx was pulled-down successfully (lower panel), and anti-IE1 antibody was used to detect the target protein (main panel). (B) Schematic showing the point replacement of cysteine residues by serine residues in the Trx mutants. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis to confirm the expression of the purified Trx and its mutants that were used in the pull-down assay. Five micrograms Trx or Trx mutants were loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE. The results were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (D) The pull-down assay for the Trx mutants was conducted in the presence of diamide (1 mM to a total volume of 200 μl). All other conditions were the same as those described above. β-ME, β-mercaptoethanol; DTT, dithiothreitol; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; Trx, thioredoxin.

Oxidative stress promotes PmTrx binding to WSSV IE1 in Sf9 cells

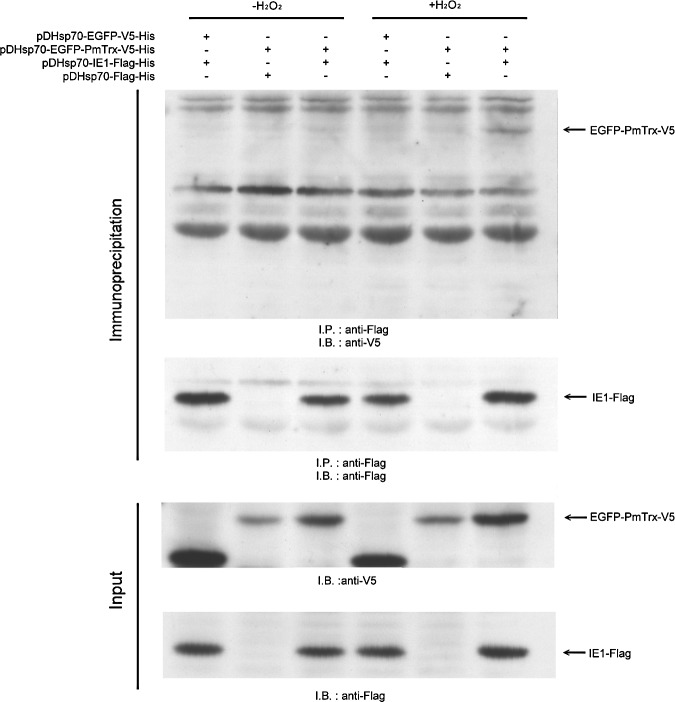

Based on the vectors pDHSP70-V5-His and pDHSP70-Flag-His (17), we constructed the V5-tagged EGFP-PmTrx plasmid pDHsp70-EGFP-PmTrx-V5-His and the Flag-tagged IE1 plasmid pDHsp70-IE1-Flag-His. After Sf9 cells were cotransfected for 16–18 h with these two plasmids, oxidative stress was applied for 30 min using 5 mM H2O2. When the cell lysates were subjected to a coimmunoprecipitation assay, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-PmTrx fusion protein only produced a clear signal under the conditions of oxidative stress (Fig. 3, upper panel).

FIG. 3.

PmTrx binds to WSSV IE1 in oxidatively stressed Sf9 cells. The upper panel shows the coimmunoprecipitation of the V5-tagged EGFP-PmTrx fusion protein with the Flag-tagged WSSV IE1. Sf9 cells were cotransfected with plasmids containing EGFP-PmTrx-V5, IE1-Flag, or vector plasmid as indicated. Six hours after heat shock, the transfected cells were treated with 5 mM H2O2 as indicated, and 30 min later the cells were harvested. The faint signals in lanes 3, 4, and 5 are due to a nonspecific interaction between Trx and the pull-down resin. Anti-Flag antibody was used to confirm that the WSSV IE1 was precipitated successfully (immunoprecipitation, lower panel). Western blotting was used to confirm the expression of the inputs (lower panels). EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

Redox controls the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1

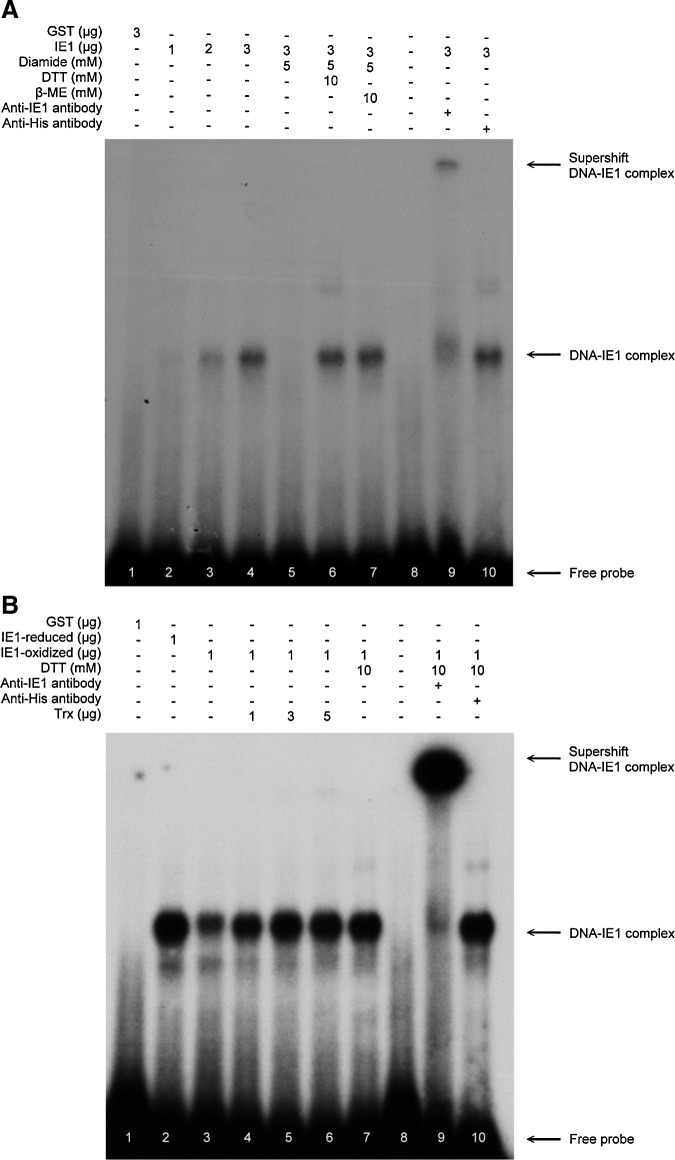

Our previous study showed that WSSV IE1 has DNA binding activity (25). Since the DNA binding activity of some transcriptional factors is known to be regulated by changes in their redox status, we speculated that the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1 might also be controlled by redox and further that PmTrx might restore the DNA binding activity of inactived, oxidized WSSV IE1 by converting it into the reduced form. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed to investigate this hypothesis. As found previously (25), the DNA binding activity of IE1 increased with increasing IE1 concentration (Fig. 4A, lanes 2–4). This binding activity was abolished by the addition of the thiol-specific reagent diamide in lane 5. However, with the further addition of the reducing agents DTT and beta mercaptoethanol (β-ME), IE1's DNA binding ability was restored (Fig. 4A, lanes 6, 7). We next investigated whether PmTrx could restore the DNA binding activity of oxidized WSSV IE1. Preliminary studies showed that Trx itself was oxidized by diamide and thus lost its disulfide reducing activity (data not shown). We therefore used a centricon device to remove the diamide (or DTT) after it had been used to produce the oxidized (or reduced) form of WSSV IE1. Figure 4B, lanes 2 and 3 show that, as expected, the oxidized form of WSSV IE1 had a lower DNA binding activity than the reduced form. The figure also shows that the DNA binding activity of the oxidized IE1 was recovered by incubating with increasing concentrations of PmTrx (Fig. 4B, lanes 4–6). These results strongly suggest that the redox status of WSSV IE1 controls its DNA binding activity and that PmTrx is likely to be involved in this control mechanism.

FIG. 4.

Redox modulation of the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1. (A) The DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1 was down-regulated by the thio-specific oxidant diamide. For this EMSA, the purified IE1 protein was preincubated at room temperature with 5 mM diamide for 30 min, followed by treatment with 10 mM DTT or 10 mM β-ME for 30 min, and incubation with the α-32P labeled probe for 30 min (lanes 5–7). Other protocols were as indicated by the lane headings. Lanes 9 and 10 include incubation with an IE1-specific and non-specific (anti-His) antibody, respectively, and confirm that the DNA-protein complex included IE1. (B) Trx restores the DNA binding activity of oxidized WSSV IE1. In this EMSA, purified oxidized IE1 protein (1 μg) was incubated with 1–5 μg of PmTrx (lanes 4–6). Other protocols were as indicated in the lane headings. EMSA, electrophoresis mobility shift assay.

Three IE1 cysteine residues are critical for its DNA binding activity

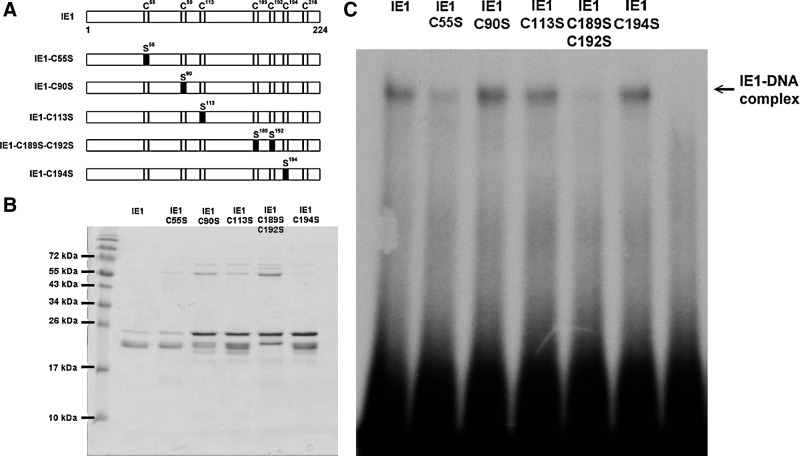

Although we tried to produce point mutants for all seven of the cysteine residues in IE1, we were only able to express and purify four single mutants (C55S, C90S, C113S, and C196S) and one double mutant (C189S-C192S) in sufficient quantity (Fig. 5A, B). Our EMSA results show that the DNA binding activity of C55S and the CXXC motif double-mutant IE1-C189S-C192S was markedly decreased (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Identifying the WSSV IE1 cysteine residues that are critical for DNA binding activity. (A) Schematic showing the point replacement of cysteine residues by serine residues in the WSSV IE1 mutants. (Note: IE1-C216S is not shown because we were unable to express and purify this mutant in sufficient quantify.) (B) To confirm protein expression, 1 μg of the purified IE1 and its mutants was loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (C) EMSA reaction using the protocol described above. IE1-DNA complex is indicated by the arrow.

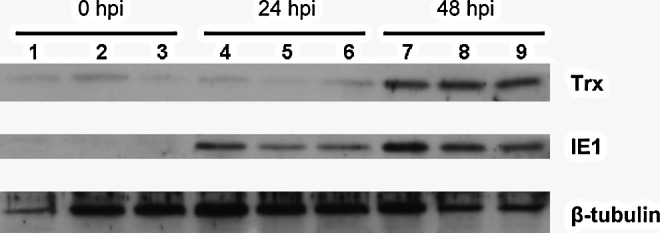

Irreversible sulfhydryl modifying reagent inhibits the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1

As a more practical alternative to the simultaneous mutation of all seven IE1 cysteine residues, we used the irreversible SH-modifying agent iodoacetamide (IAM) to alkylate all of the free cysteine residues on IE1. After IAM treatment, the DNA binding activity of IE1 was totally lost and no longer under redox control (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Irreversible sulfhydryl modifying reagent IAM inhibits the DNA binding activity of WSSV IE1. (A) Purified IE1 was treated with 5 mM IAM for 30 min, loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The panel shows that there was no degradation of IE1 protein after IAM treatment. (B) IE1 or IAM-treated IE1 was treated with 5 mM diamide for 30 min, and then 15 mM DTT for another 30 min as indicated by the lane headings. The EMSA result suggests that IAM treatment successfully alkylated all of the free cysteine residues and irreversibly prevented formation of the IE1-DNA complex. IAM, iodoacetamide.

Oxidative stress was observed in WSSV-infected shrimps at 48 hpi

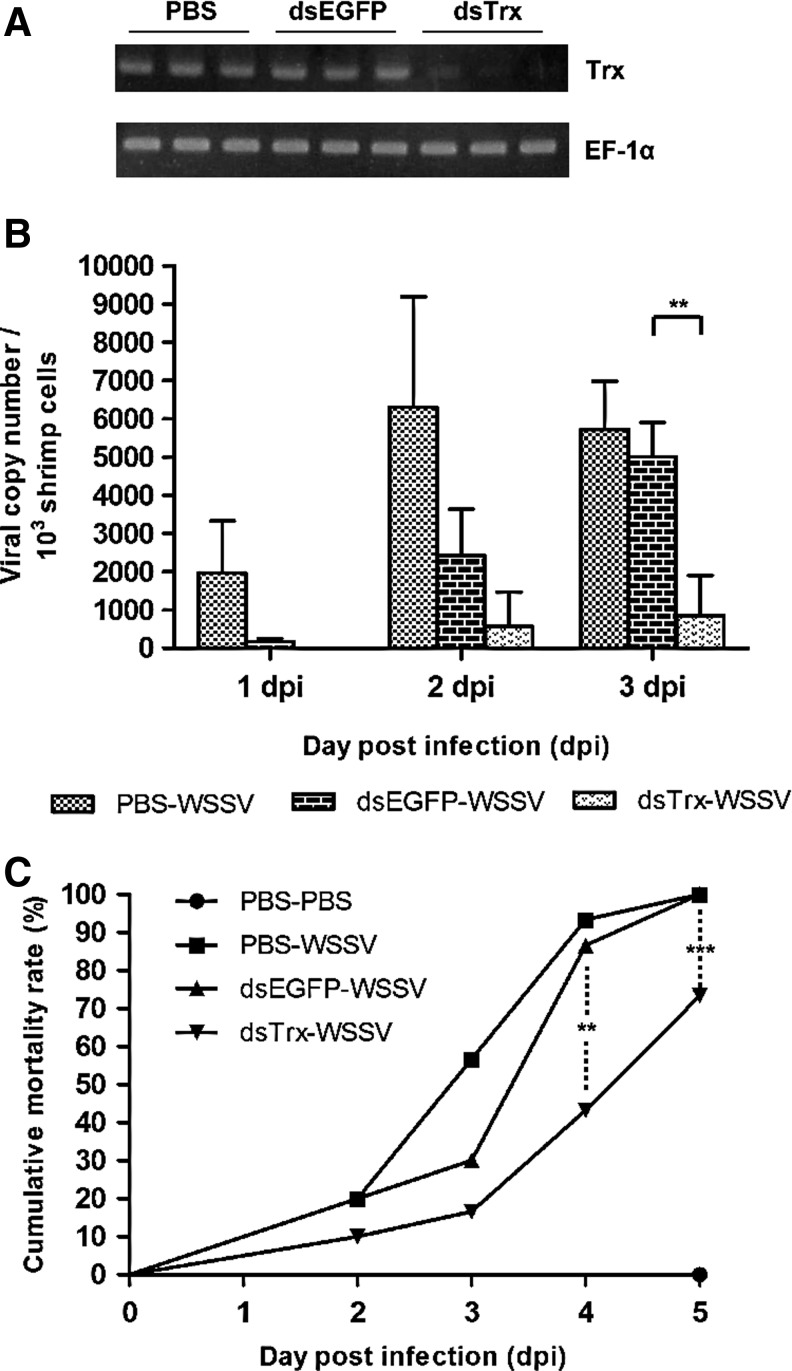

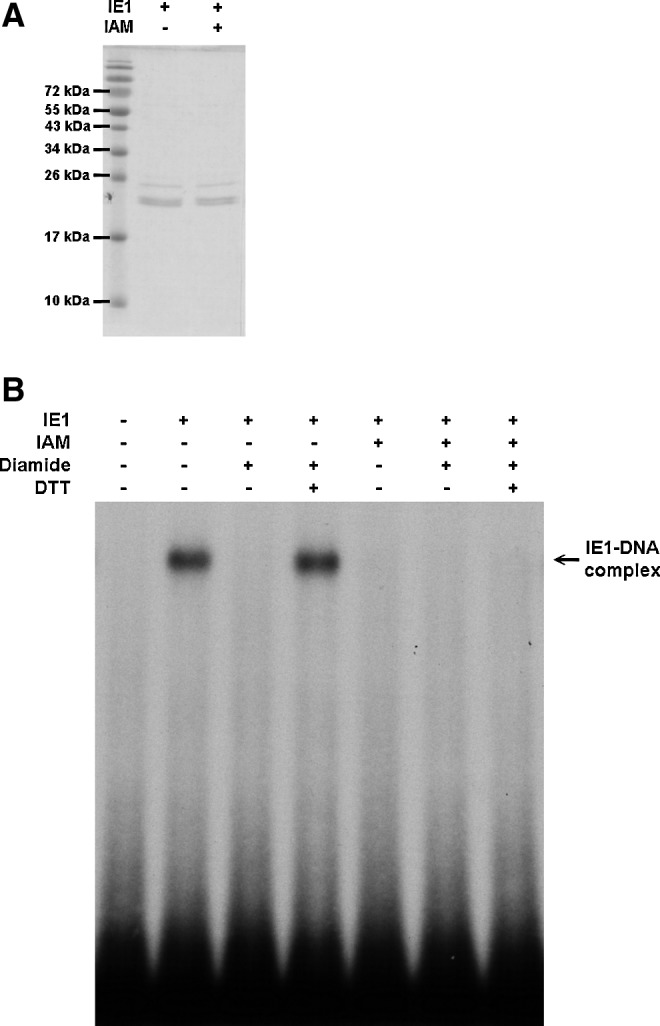

To monitor the cellular redox state during WSSV infection, the ratio of reduced glutathione to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) was measured using an LC/ESI/MS system. In phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected shrimps, the GSH/GSSG ratio ranged from 10 to 25, but in WSSV-infected shrimps, the ratio was significantly up-regulated at 24 hpi, and significantly down-regulated at 48 hpi (Fig. 7A). Figure 7B shows the corresponding increase in viral copy number in the sampled WSSV-infected groups at the same time points.

FIG. 7.

Oxidative stress in WSSV-infected shrimps. (A) Shrimps (n=4 for each group; at least three different groups for each time point) were injected with WSSV inoculum or PBS, and the GSH/GSSG ratio was measured at 12, 24, 36, 48 h after challenge. (B) A real-time PCR quantification of the WSSV viral load. Data represent WSSV copy numbers in WSSV-infected shrimp at 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after challenge. Samples were taken from the same experimental shrimps that were used in the GSH/GSSG assay, and quantified in duplicate. All values are means±SD. An asterisk indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation.

Suppression of the shrimp Trx gene significantly reduces the mortality rate after challenge with WSSV

To explore the in vivo role of Trx during a WSSV infection, Trx expression was suppressed by a dsRNA-mediated RNA interference (33). Two days after injection, an RT-PCR confirmed that Trx was suppressed (Fig. 8A). When the dsTrx-treated shrimps were challenged with WSSV, we found that their viral copy numbers were lower than those in the dsEGFP control group at day 2, and this reduction reached statistical significance at day 3 (Fig. 8B). In the dsTrx-WSSV group, the cumulative mortality rate was also significantly lower at 3, 4, and 5 days postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

dsRNA silencing of the shrimp Trx gene and its effects on WSSV challenge. (A) Reverse transcriptase–PCR of total RNA extracted from gill tissue showed that expression of the shrimp Trx gene was suppressed 2 days after injection with Trx dsRNA. PBS and EGFP dsRNA were used as controls. Each lane represents an individual shrimp. EF-1α was used as the internal control. (B) Real-time PCR was used to quantify the WSSV viral load in WSSV-infected shrimp at 1, 2, and 3 days postinfection. Three shrimps were taken at each time point and quantified in duplicate. All values are means±SD. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p<0.01). (The viral copy number for the dsTrx-WSSV group at day 1 is too low to be seen in the figure.) (C) Shrimp (n=30 for each group) were injected with Trx dsRNA, EGFP dsRNA, or PBS 2 days prior to WSSV challenge (or PBS injection). Data are presented using a Kaplan–Meier plot. A log rank χ2 test found that the dsTrx-injected shrimps had significantly lower mortality than the dsEGFP-injected shrimps at 4 dpi (p<0.01) and 5 dpi (p<0.005). dpi, days postinfection; dsRNA, double strand RNA.

Discussion

Trx acts as a hydrogen donor that breaks disulfide bonds by transferring reducing equivalents to the disulfide groups in target proteins such that the oxidized disulfide (–S2) form is converted to the reduced dithiol [–(SH)2] form (11). Sequencing and alignment of the cDNA sequence of Trx from P. monodon showed that although PmTrx shares more than 90% identity with Litopenaeus vannamei Trx and Fenneropenaeus chinensis Trx, it is only around 50% identical to human Trx-1 (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Although none of the shrimp Trxs is highly similar to human Trx-1, they still exhibit disulfide-reducing activity (1). Sequence analysis further showed that like the other shrimp Trxs, PmTrx has four cysteines (Cys32, Cys35, Cys62, and Cys73), including the highly conserved catalytic site (-Cys32-Gly-Pro-Cys35-).

However, PmTrx-WSSV IE1 binding is evidently not mediated by the catalytic site because, as Figure 2 shows, the wild-type PmTrx and the single and double mutants are still able to bind to WSSV IE1. Binding is only prevented in the two mutants, where Cys62 has been replaced by serine. Wang et al. (44) found that the binding between human Trx1 and actin is likewise independent of the catalytic site of Trx and that it is mediated via Cys62 instead. We propose that a similar mechanism involving a disulfide bond at PmTrx Cys62 is also responsible for the interaction between PmTrx and WSSV IE1. Figure 2 also shows that PmTrx only binds to WSSV IE1 in the presence of oxidizing reagent diamide, which suggests that binding is under redox control.

PmTrx was also found to interact with WSSV IE1 in the absence of diamide in Sf9 cells exposed to oxidative stress (Fig. 3). These in vitro oxidizing conditions were designed to emulate those produced by a respiratory burst, which is an innate immune response in shrimp that causes the release of reactive oxygen species, including hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals. Indirect experimental evidence has already suggested that a respiratory burst is produced in shrimp in response to WSSV infection (47), and our new data show that oxidative stress does indeed occur in WSSV-infected shrimp at 48 hpi (Fig. 7A). We hypothesize that under the conditions of Figure 3, H2O2 probably oxidizes an IE1 thiol group to produce a sulfenic acid (–SOH), which then interacts with a thiol group on PmTrx to form a disulfide bond. If no PmTrx is present, then the IE1 sulfenic acid would presumably form an intramolecular disulfide bond.

The replication cycle of WSSV is completed within 24 h (45), and at this time, lysis will start to occur in some infected cells. However, at 24 hpi, Figure 7A shows an increased GSH/GSSH ratio, suggesting that reducing conditions are maintained in the cytosol of most cells at this time. In the intact cells, reducing conditions would provide a good environment for protein synthesis, which would be favorable to both viral progression and the host defenses. As the infection progresses through a second viral replication cycle, the number of infected cells increases exponentially (2), and these favorable conditions can no longer be maintained; consequently, oxidative stress is seen in Figure 7A at 48 hpi, which is close to the moribund stage of WSSV infection (i.e., when almost all of the cells will have lysed). [We should note that when Mohankumar and Ramasamy (31) monitored redox conditions using different methods, they reported a steady increase in oxidative stress in WSSV-infected Fenneropenaeus indicus. The reason for the discrepancy between their data and Fig. 7A is not yet known.]

The DNA binding activity of IE1 appears to depend on three of its cysteine residues, two of which (Cys189 and Cys192) comprise a CXXC motif (Fig. 5). The third residue important for DNA binding activity, Cys55, is located in the transactivation domain of IE (25), and we hypothesize that this cysteine residue might be essential because of some conformational change that it induces in IE1's structure.

The PmTrx/WSSV IE1 pull-down results (Fig. 2) suggest a redox-dependent interaction that is mediated by a disulfide bond. Figure 4 shows further evidence of a redox-dependent interaction between these two proteins. Specifically, PmTrx is able to reduce the oxidized form of IE1 and restore its DNA binding activity. In addition to these in vitro results, our dsRNA experiment shows that knockdown of shrimp Trx reduces both viral copy number and mortality in WSSV-challenged shrimp (Fig. 8). We hypothesize that these effects are mediated by the same interactions we demonstrated in vitro and that they are under redox control. In further support of this hypothesis, we note that a redox-controlled interaction between Trx and WSSV IE1 would presumably be of benefit to the virus in the oxidizing conditions that are usually induced during viral infection (34). As already shown (Fig. 7A), oxidizing conditions do indeed exist in shrimp at 48 h post challenge. In the absence of sufficient PmTrx, this means that IE1 would be oxidized and has no DNA binding activity. However, since PmTrx is up-regulated at this time (Fig. 1), it might restore (or maintain) IE1 to its reduced form and thus restore its DNA binding activity. [We note that WSSV IE1 is unlike most other immediate early genes in that it is highly expressed throughout the infection cycle (24), even though IE1's actual functions–if any–after the immediate early stage are presently unknown.]

Materials and Methods

Virus inoculum, shrimp, and virus challenge

The virus used in this study was the WSSV Taiwan isolate (AF440570) (3). Virus stock was prepared as described previously (39) and was stored at −80°C until use. The WSSV inoculum was prepared from the supernatant of the virus stock by centrifugation at 3000 g (10 min) and further dilution (10−2) with PBS as described previously (39).

The shrimps used in the immunoblotting assay and in the supplemental experiments were WSSV-free P. monodon (35–55 g) obtained from Tung-Kung Marine Laboratory, Taiwan Fisheries Research Institute. Shrimps in the experimental groups were challenged by intramuscular injection with 100 μl of virus inoculum (100× dilution of the viral stock), while shrimps in the control groups were injected with 100 μl PBS. All shrimps were cultured in 500 L tanks containing seawater (33‰ salinity) with a mean ambient temperature of 25°C. At various time points (0, 6, 24, and 48 h) after injection, the gills of the experimental shrimps (n=3) and control shrimps (n=3) were collected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

The shrimps used in the redox monitoring experiment were WSSV-free L. vannamei (∼10 g body weight) obtained from a commercial farm located in Pingtung, Taiwan. Shrimps in the experimental groups were challenged by intramuscular injection with 50 μl of virus inoculum (200× dilution of the viral stock), while shrimps in the control groups were injected with 50 μl PBS. All shrimps were cultured in 500 L tanks containing seawater (33‰ salinity) with a mean ambient temperature of 25°C. At various time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 h) after injection, the stomachs of the experimental shrimps (three groups; each group contained four shrimps) and control shrimps (three groups; each group contained four shrimps) were collected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C

The shrimps used in the dsRNA-mediated Trx knockdown experiment were WSSV-free L. vannamei (∼5 g body weight) obtained from the Terrestrial Animal Experimental Center, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan. After specific gene suppression, shrimps in the experimental groups were challenged by intramuscular injection with 100 μl of virus inoculum (2000× dilution of the viral stock), while shrimps in the control groups were injected with 100 μl PBS. Shrimps were cultured in 100 L tanks containing seawater (33‰ salinity) with a mean ambient temperature of 25°C.

Anti-Trx and anti-WSSV IE1 antibodies

For the immunoblottings, anti-Trx and anti-WSSV IE1 antibodies were prepared by cloning the PmTrx or WSSV ie1 coding sequence into the pET28b vector (see Table 3 and 4 for primers). The resulting constructs, pET28b-Trx and pET28b-WSSVIE1, respectively, were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 Codon Plus cells. Recombinant proteins were purified on an Amicon Ultra-30 column (Millipore) and then separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Anti-Trx antibody and anti-WSSV IE1 antibodies were raised in rabbit using the purified recombinant PmTrx or WSSV IE1 as the antigen according to the conventional methods (15).

Table 3.

The Primer Sets Used for the Construction of Various Expression Plasmids

| Plasmid | Primer sets | Usage | Vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| pET28b-IE1 | IE1-F/IE1-R | Protein expression | pET-28b |

| pET28b-Trx | Trx-F/Trx-R | Protein expression | pET-28b |

| pET28b-sm-Trxa | smTrx-F/smTrx-R | Protein expression | pET28b-Trx |

| pET28b-dm-Trxb | dmTrx-F/dmTrx-R | Protein expression | pET28b-Trx |

| pET28b-tm-Trx-C62Sc | tmTrx-C62S-F/tmTrx-C62S-R | Protein expression | pET28b-dm-Trx |

| pET28b-tm-Trx-C73Sc | tmTrx-C73S-F/tmTrx-C73S-R | Protein expression | pET28b-dm-Trx |

| pET28b-qm-Trxd | tmTrx-C73S-F/tmTrx-C73S-R | Protein expression | pET28b-tm-Trx-C62S |

| pGEX5T-1-IE1-C55S | IE1-C55S-F/IE1-C55S-R | Protein expression | pGEX5T-1-IE1 |

| pGEX5T-1-IE1-C90S | IE1-C90S-F/IE1-C90S-R | Protein expression | pGEX5T-1-IE1 |

| pGEX5T-1-IE1-C113S | IE1-C113S-F/IE1-C113S-R | Protein expression | pGEX5T-1-IE1 |

| pGEX5T-1-IE1-C189S-C192S | IE1-C189S-C192S-F/IE1-C189S-C192S-R | Protein expression | pGEX5T-1-IE1 |

| pGEX5T-1-IE1-C194S | IE1-C194S-F/IE1-C194S-R | Protein expression | pGEX5T-1-IE1 |

| pDHsp70-EGFP-V5-His | EGFP-V5-F/EGFP-V5-R | Coimmunoprecipitation | pDHsp70-V5-His |

| pDHsp70-EGFP-PmTrx-V5-His | Trx-V5-F/Trx-V5-R | Coimmunoprecipitation | pDHsp70-EGFP-V5-His |

| pDHsp70-IE1-Flag-His | IE1-Flag-F/IE1-Flag-R | Coimmunoprecipitation | pDHsp70-Flag-His |

sm, single mutation.

dm, double mutation.

tm, triple mutation.

qm, quadruple mutation.

Table 4.

Primer Sequences Used in This Study

| Primer sets | Primer sequences (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| IE1-F | 5′-CCCGGATCCGATGGCCTTTAATTTTGAAGA-3′ |

| IE1-R | 5′-GGGCTCGAGTACAAAGAATCCAGAAATC-3′ |

| Trx-F | 5′-CCGGGATCCGATGGTGTACCAAGTGAAAGATC-3′ |

| Trx-R | 5′-CCCCTCGAGCTTGTGCTTCTCGATGAGTTC-3′ |

| smTrx-F | 5′-TCCAAAATGATTGCACCTAAG-3′ |

| smTrx-R | 5′-TGGCCCACACCAGGTGGCGTAG-3′ |

| dmTrx-F | 5′-TCCAAAATGATTGCACCTAAG-3′ |

| dmTrx-R | 5′-TGGCCCAGACCAGGTGGCG-3′ |

| tmTrx-C62S-F | 5′-GAATCCGAAGACATTGCCC-3′ |

| tmTrx-C62S-F | 5′-GTCCACATCCACCTTCAGG-3′ |

| tmTrx-C73S-F | 5′-GCATCCATGCCTACTTTTCTG-3′ |

| tmTrx-C73S-F | 5′-AATCTGGTTATCTTGGGC-3′ |

| IE1-C55S-F | 5′-AAGTCTGGGAATTTTGAAGC-3′ |

| IE1-C55S-R | 5′-TCCTTGCCGTACGAGACGCC-3′ |

| IE1-C90S-F | 5′-ACAAACTCCTTGGCATTATTC-3′ |

| IE1-C90S-R | 5′-CTTGACATGGGAACCACTGTTG-3′ |

| IE1-C113S-F | 5′-TACTCTACTTTTCCCCAATAC-3′ |

| IE1-C113S-R | 5′-CTGTCCATGTCGATCAGTCTC-3′ |

| IE1-C189S-C192-F | 5′-TATCTAATGCGTCTAGGTGC-3′ |

| IE1-C189S-C192-R | 5′-CAGAAAACATTGGGTTTGAT-3′ |

| IE1-C194S-F | 5′-AGGTCCAAGTACCCAGGCCC-3′ |

| IE1-C194S-R | 5′-ACACGCATTACATACAGAAAAC-3′ |

| EGFP-V5-F | 5′-CCCAAGCTTACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3′ |

| EGFP-V5-R | 5′-CGCGGATCCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ |

| Trx-V5-F | 5′-GGGCCGCGGATGGTGTACCAAGTGAAAGA-3′ |

| Trx-V5-R | 5′-GGGCCGCGGCTTGTGCTTCTCGATGAGTT-3′ |

| IE1-Flag-F | 5′-CCCAAGCTTCTCAAGATGGCCTTTAATTTTG-3′ |

| IE1-Flag-R | 5′-TCCCCGCGGTACAAAGAATCCAGAAATCTCA-3′ |

Restriction enzyme cutting sites and mutated sites are underlined.

Immunoblotting

Total protein was extracted from the excised P. monodon stomachs using a three-fold dilution of PBS. Samples of extracted protein (20 μg) were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE, and the separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). PmTrx was detected with rabbit anti-Trx primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Chemicon). WSSV IE1 was detected with rabbit anti-WSSV IE1 primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Chemicon). P. monodon β-tubulin was used as the internal control and detected with rabbit anti-β-tubulin primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Chemicon). Target signals were visualized by an ECL system (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of recombinant IE1 and IE1 mutants

GST-IE1 fusion proteins were produced by transforming Escherichia coli BL21 Codon Plus cells with the plasmids pGEX5T-1 and pGEX5T-1-IE1 as described previously (25) with slight modifications. IE1 protein was obtained from the purified GST-IE1 by using a protease, factor Xa (10 units/1 mg GST fusion protein; Novagen), to remove the GST as described previously (25).

For the production of IE1 mutants, plasmids to express four single mutants (Cys55→Ser55, pGEX5T-1-IE1-C55S; Cys90→Ser90, pGEX5T-1-IE1-C90S; Cys113→Ser113, pGEX5T-1-IE1-C113S; and Cys196→Ser196, pGEX5T-1-IE1-C196S;) and one double mutant (Cys189,192→Ser189,192, pGEX5T-1-IE1-C189-192S) were then constructed by rolling-circle PCR using pGEX5T-1-IE1 as a template. After transformation of these constructs into Escherichia coli strain BL21 Codon Plus cells, the recombinant IE1 mutants were purified as described above. Primersets are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Expression and purification of recombinant PmTrx and PmTrx mutants

For the production of recombinant PmTrx, the PmTrx coding sequence was cloned into the pET28b vector by PCR amplification. Plasmids to express the four mutants (Cys32→Ser32, pET28b-smTrx; Cys32,35→Ser32,35, pET28b-dmTrx, Cys32,35,62→Ser32,35,62, pET28b-tmTrx-C62S; Cys32,35,73→Ser32,35,73, pET28b-tmTrx-C73S; Cys32,35,62,73→Ser32,35,62,73, pET28b-qmTrx) were then constructed by rolling-circle PCR using pET28b-Trx, pET28b-dmTrx or pET28b-tmTrx-C62S as a template. After transformation of these constructs into Escherichia coli strain BL21 Codon Plus cells, the recombinant Trx, smTrx, dmTrx, tmTrx-C62S, tmTrx-C73S, and qmTrx proteins were purified without the use of reducing agents. Primers are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Pull-down assays

To test whether PmTrx binds to WSSV IE1, purified recombinant Trx was mixed with IE1 in the presence of 1 mM DTT or 1 mM diamide. To identify which Trx cysteine residues are necessary for IE1 binding, Trx and its mutants were mixed with purified IE1 in the presence of 1 mM diamide. The His-tagged Trx and Trx mutants were pulled down using nickel-agarose beads (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Anti-Trx antibody was used to confirm pull down, and anti-IE1 antibody was used to detect the target protein.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay in Sf9 cells

Plasmids to express WSSV-IE1 and PmTrx proteins were constructed, respectively, from Drosophila heat shock protein 70 promoter-based expression vectors pDHsp70-Flag-His and pDHsp70-V5-His (17). To express IE1, the Flag-tagged WSSV IE1 expression plasmid, pDHsp70-IE1-Flag-His, was constructed by PCR using WSSV genomic DNA as a template. Expression of PmTrx was slightly more complicated: because the PmTrx coding regions are so short, the EGFP sequence was isolated from a commercial plasmid pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) by PCR and cloned into the pDHsp70-V5-His vector to produce pDHsp70-EGFP-V5-His. The V5-tagged EGFP-PmTrx expression plasmid pDHsp70-EGFP-PmTrx-V5-His was then constructed by PCR using pET28b-rTrx as a template.

For the coimmunoprecipitation assay, Sf9 cells (8×105 cell/well) were cotransfected with the above plasmids using an Effectene transfection kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After transfection (16–18 h), exposure to 5 mM H2O2 or PBS for 30 min and harvesting, proteins were pulled down with 15 μl anti-FLAG M2 agarose gel (Sigma), separated on 17.5% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). A V5-tagged protein was detected with rabbit anti-V5 primary antibody (Sigma) and goat anti-rabbit (Chemicon) secondary antibody. Flag-tagged protein was detected with rabbit anti-Flag primary antibody (Sigma) and goat anti-rabbit (Chemicon) secondary antibody. Targets signal were visualized using an ECL system (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSAs used a 79 mer oligonucleotide (5′-GTCGCTCGA GCGGTATGACGAGATCTA(N)25TAGATCTGCGTCACTA GTCTAGACTAG-3′) as a random probe and were performed exactly as described previously (25) except that the quantity of poly(dI-dC) was reduced from 200 to 50 ng.

GSH/GSSG ratio measurement

The GSH/GSSG ratio was monitored because it serves as a good indicator of the cellular redox state (7, 32). Total metabolic materials were extracted from the L. vannamei stomach using cold 100% MeOH (tissue weight [mg]: buffer [μl] 1:20). The extracted lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was dried using a centrifugal evaporator (CVE-2000, EYELA). The pellet was suspended in a volume of deionized water that was equal to the original volume of the buffer. The reduced and oxidized forms of glutathione (GSH and GSSG) were measured by a LC/ESI/MS system in positive electrospray ionization.

WSSV copy number quantification

WSSV copy number quantification was performed using the commercial real-time PCR kit for viral load quantification (GeneReach Biotechnology Corp.) as described previously (22). Results were presented as means±standard deviation. Quantified data were analyzed using the Student's t-test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The effect of dsRNA-mediated Trx knockdown on WSSV-infected shrimps

Double-strand shrimp Trx RNA (dsTrx RNA) was generated by using the T7 RiboMAX Express Large Scale RNA System (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the DNA template of L. vannamei Trx and T7 promoter was generated by PCR amplification with the appropriate primers (LvTrx-ds-F/LvTrx-ds-R, 5′-ATGGTTTACCAAGTGAAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTGTTCTTCTCAACGAGTTC-3′; Lv-Trx-T7ds-F/Lv-Trx-T7ds-R 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGG GAGAATGGTTTACCAAGTGAAAG-3′ and 5′-TAATACGA CTCACTATAGGGAGACTTGTTCTTCTCAACGAGTTC-3′) for the single-strand RNA. The dsEGFP RNA was obtained as described previously (43). The experimental shrimps were treated with dsTrx or dsEGFP RNA at a dosage of 1 μg/g shimp in 100 μl PBS by intramuscular injection. A negative control group was injected with 100 μl PBS only.

To monitor the silencing effect, 2 days after dsRNA injection, the gills of the experimental group (dsTrx) and control groups (dsEGFP and PBS) were collected. RNA was extracted, and cDNA was obtained using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and Superscriptase III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was used to confirm the gene suppression effect with the primers sets (LvTrx-F/LvTrx-R, 5′-ACTGCTCTCTCTGGCACCAAG-3′ and 5′-ATTCACCTGAAATAATTAGC-3′; EF-1α-F/EF-1α-R, 5′-ATGGTTGTCAACTTTGCCC-3′ and 5′-TTGACCTCCTTGATCACACC-3′).

For the WSSV copy number experiment, the pleopods of the experimental shrimps (dsTrx-WSSV injected) and control shrimps (PBS-WSSV injected and dsEGFP-WSSV injected) were collected at various time points (1, 2, and 3 dpi; three shrimps in each sample), frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. To determinate the WSSV copy number, the viral load was quantified using a real-time PCR as described above.

For the cumulative mortality experiment, shrimps (n=30 in each group) were injected with dsTrx, dsEGFP, or PBS only by intramuscular injection 2 days prior to WSSV challenge. Mortality was monitored every 12 h and recorded every day. Data were processed with the GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) and presented using a Kaplan–Meier plot. Statistical significance was determined using the log rank χ2 test.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- β-ME

β-mercaptoethanol

- dsRNA

double-strand RNA

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- IAM

iodoacetamide

- LC/ESI/MS

liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry

- ORF

open reading frames

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PmTrx

Penaeus monodon thioredoxin

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

- SSC

saline sodium citrate

- Trx

thioredoxin

- WSSV

white spot syndrome virus

- WSSV IE1

WSSV immediate early protein #1

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported financially by National Science Council grants (100-2311-B-002-005-MY3 and 100-2321-B-002-025) and a National Taiwan University grant (CESRP-10R70602B5). The WSSV-free P. monodon shrimps were kindly provided by Kuan Fu Liu from Tung-Kung Marine Laboratory, Taiwan Fisheries Research Institute. We thank Chun Han Ho and Yu-Hsuan Tung for their helpful comments. We thank Paul Barlow for his helpful criticism of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aispuro-Hernandez E. Garcia-Orozco KD. Muhlia-Almazan A. Del-Toro-Sanchez L. Robles-Sanchez RM. Hernandez J. Gonzalez-Aguilar G. Yepiz-Plascencia G. Sotelo-Mundo RR. Shrimp thioredoxin is a potent antioxidant protein. Comp Biochem Physiol C-Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;148:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen IT. Aoki T. Huang YT. Hirono I. Chen TC. Huang JY. Chang GD. Lo CF. Wang HC. White spot syndrome virus induces metabolic changes resembling the Warburg effect in shrimp hemocytes in the early stage of infection. J Virol. 2011;85:12919–12928. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05385-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen LL. Leu JH. Huang CJ. Chou CM. Chen SM. Wang CH. Lo CF. Kou GH. Identification of a nucleocapsid protein (VP35) gene of shrimp white spot syndrome virus and characterization of the motif important for targeting VP35 to the nuclei of transfected insect cells. Virology. 2002;293:44–53. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LL. Wang HC. Huang CJ. Peng SE. Chen YG. Lin SJ. Chen WY. Dai CF. Yu HT. Wang CH. Lo CF. Kou GH. Transcriptional analysis of the DNA polymerase gene of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. Virology. 2002;301:136–147. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen WY. Ho KC. Leu JH. Liu KF. Wang HC. Kou GH. Lo CF. WSSV infection activates STAT in shrimp. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:1142–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabianek RA. Hennecke H. Thony-Meyer L. Periplasmic protein thiol:disulfide oxidoreductases of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraternale A. Paoletti MF. Casabianca A. Nencioni L. Garaci E. Palamara AT. Magnani M. GSH and analogs in antiviral therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han F. Xu J. Zhang X. Characterization of an early gene (wsv477) from shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) Virus Genes. 2007;34:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s11262-006-0053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He F. Fenner BJ. Godwin AK. Kwang J. White spot syndrome virus open reading frame 222 encodes a viral E3 ligase and mediates degradation of a host tumor suppressor via ubiquitination. J Virol. 2006;80:3884–3892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3884-3892.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He F. Kwang J. Identification and characterization of a new E3 ubiquitin ligase in white spot syndrome virus involved in virus latency. Virol J. 2008;5:151. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C. Zhang X. Lin Q. Xu X. Hu Z. Hew CL. Proteomic analysis of shrimp white spot syndrome viral proteins and characterization of a novel envelope protein VP466. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:223–231. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100035-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y. Domann FE. Redox modulation of AP-2 DNA binding activity in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:307–312. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadokura H. Katzen F. Beckwith J. Protein disulfide bond formation in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leenaars PPAM. Hendriksen CFM. de Leeuw WA. Carat F. Delahaut P. Fischer R. Halder M. Hanly WC. Hartinger J. Hau J. Lindblad EB. Nicklas W. Outschoorn IM. Stewart-Tull DES. The production of polyclonal antibodies in laboratory animals - The report and recommendations of ECVAM Workshop 35. Atla-Altern Lab Anim. 1999;27:79–102. doi: 10.1177/026119299902700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leu JH. Chang CC. Wu JL. Hsu CW. Hirono I. Aoki T. Juan HF. Lo CF. Kou GH. Huang HC. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in normal and white spot syndrome virus infected Penaeus monodon. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leu JH. Kuo YC. Kou GH. Lo CF. Molecular cloning and characterization of an inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) from the tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leu JH. Tsai JM. Wang HC. Wang AH. Wang CH. Kou GH. Lo CF. The unique stacked rings in the nucleocapsid of the white spot syndrome virus virion are formed by the major structural protein VP664, the largest viral structural protein ever found. J Virol. 2005;79:140–149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.140-149.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F. Li M. Ke W. Ji Y. Bian X. Yan X. Identification of the immediate-early genes of white spot syndrome virus. Virology. 2009;385:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin F. Huang H. Xu L. Li F. Yang F. Identification of three immediate-early genes of white spot syndrome virus. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1611–1614. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin ST. Chang YS. Wang HC. Tzeng HF. Chang ZF. Lin JY. Wang CH. Lo CF. Kou GH. Ribonucleotide reductase of shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV): expression and enzymatic activity in a baculovirus/insect cell system and WSSV-infected shrimp. Virology. 2002;304:282–290. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu WJ. Chang YS. Huang WT. Chen IT. Wang KC. Kou GH. Lo CF. Penaeus monodon TATA box-binding protein interacts with the white spot syndrome virus transactivator IE1 and promotes its transcriptional activity. J Virol. 2011;85:6535–6547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WJ. Chang YS. Wang AH. Kou GH. Lo CF. White spot syndrome virus annexes a shrimp STAT to enhance expression of the immediate-early gene ie1. J Virol. 2007;81:1461–1471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01880-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu WJ. Chang YS. Wang CH. Kou GH. Lo CF. Microarray and RT-PCR screening for white spot syndrome virus immediate-early genes in cycloheximide-treated shrimp. Virology. 2005;334:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu WJ. Chang YS. Wang HC. Leu JH. Kou GH. Lo CF. Transactivation, dimerization, and DNA-binding activity of white spot syndrome virus immediate-early protein IE1. J Virol. 2008;82:11362–11373. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ. Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makino Y. Yoshikawa N. Okamoto K. Hirota K. Yodoi J. Makino I. Tanaka H. Direct association with thioredoxin allows redox regulation of glucocorticoid receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3182–3188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masutani H. Hirota K. Sasada T. Ueda-Taniguchi Y. Taniguchi Y. Sono H. Yodoi J. Transactivation of an inducible anti-oxidative stress protein, human thioredoxin by HTLV-I Tax. Immunol Lett. 1996;54:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(96)02651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews JR. Wakasugi N. Virelizier JL. Yodoi J. Hay RT. Thioredoxin regulates the DNA binding activity of NF-kappa B by reduction of a disulphide bond involving cysteine 62. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3821–3830. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miwa K. Kishimoto C. Nakamura H. Makita T. Ishii K. Okuda N. Taniguchi A. Shioji K. Yodoi J. Sasayama S. Increased oxidative stress with elevated serum thioredoxin level in patients with coronary spastic angina. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:177–181. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960260406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohankumar K. Ramasamy P. White spot syndrome virus infection decreases the activity of antioxidant enzymes in Fenneropenaeus indicus. Virus Res. 2006;115:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman I. MacNee W. Regulation of redox glutathione levels and gene transcription in lung inflammation: therapeutic approaches. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1405–1420. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robalino J. Bartlett T. Shepard E. Prior S. Jaramillo G. Scura E. Chapman RW. Gross PS. Browdy CL. Warr GW. Double-stranded RNA induces sequence-specific antiviral silencing in addition to nonspecific immunity in a marine shrimp: convergence of RNA interference and innate immunity in the invertebrate antiviral response? J Virol. 2005;79:13561–13571. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13561-13571.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz KB. Oxidative stress during viral infection: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumida Y. Nakashima T. Yoh T. Nakajima Y. Ishikawa H. Mitsuyoshi H. Sakamoto Y. Okanoue T. Kashima K. Nakamura H. Yodoi J. Serum thioredoxin levels as an indicator of oxidative stress in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2000;33:616–622. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tassanakajon A. Klinbunga S. Paunglarp N. Rimphanitchayakit V. Udomkit A. Jitrapakdee S. Sritunyalucksana K. Phongdara A. Pongsomboon S. Supungul P. Tang S. Kuphanumart K. Pichyangkura R. Lursinsap C. Penaeus monodon gene discovery project: the generation of an EST collection and establishment of a database. Gene. 2006;384:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai JM. Wang HC. Leu JH. Hsiao HH. Wang AH. Kou GH. Lo CF. Genomic and proteomic analysis of thirty-nine structural proteins of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J Virol. 2004;78:11360–11370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11360-11370.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai JM. Wang HC. Leu JH. Wang AH. Zhuang Y. Walker PJ. Kou GH. Lo CF. Identification of the nucleocapsid, tegument, and envelope proteins of the shrimp white spot syndrome virus virion. J Virol. 2006;80:3021–3029. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3021-3029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai MF. Kou GH. Liu HC. Liu KF. Chang CF. Peng SE. Hsu HC. Wang CH. Lo CF. Long-term presence of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in a cultivated shrimp population without disease outbreaks. Dis Aquat Org. 1999;38:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai MF. Lo CF. van Hulten MC. Tzeng HF. Chou CM. Huang CJ. Wang CH. Lin JY. Vlak JM. Kou GH. Transcriptional analysis of the ribonucleotide reductase genes of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. Virology. 2000;277:92–99. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai MF. Yu HT. Tzeng HF. Leu JH. Chou CM. Huang CJ. Wang CH. Lin JY. Kou GH. Lo CF. Identification and characterization of a shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) gene that encodes a novel chimeric polypeptide of cellular-type thymidine kinase and thymidylate kinase. Virology. 2000;277:100–110. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzeng HF. Chang ZF. Peng SE. Wang CH. Lin JY. Kou GH. Lo CF. Chimeric polypeptide of thymidine kinase and thymidylate kinase of shrimp white spot syndrome virus: thymidine kinase activity of the recombinant protein expressed in a baculovirus/insect cell system. Virology. 2002;299:248–255. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang KC. Kondo H. Hirono I. Aoki T. The Marsupenaeus japonicus voltage-dependent anion channel (MjVDAC) protein is involved in white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) pathogenesis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;29:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X. Ling S. Zhao D. Sun Q. Li Q. Wu F. Nie J. Qu L. Wang B. Shen X. Bai Y. Li Y. Redox regulation of actin by thioredoxin-1 is mediated by the interaction of the proteins via cysteine 62. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:565–573. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YG. Hassan MD. Shariff M. Zamri SM. Chen X. Histopathology and cytopathology of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in cultured Penaeus monodon from peninsular Malaysia with emphasis on pathogenesis and the mechanism of white spot formation. Dis Aquat Organ. 1999;39:1–11. doi: 10.3354/dao039001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z. Chua HK. Gusti AA. He F. Fenner B. Manopo I. Wang H. Kwang J. RING-H2 protein WSSV249 from white spot syndrome virus sequesters a shrimp ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, PvUbc, for viral pathogenesis. J Virol. 2005;79:8764–8772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8764-8772.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeh SP. Chen YN. Hsieh SL. Cheng WT. Liu CH. Immune response of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, after a concurrent infection with white spot syndrome virus and infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;26:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X. Huang C. Tang X. Zhuang Y. Hew CL. Identification of structural proteins from shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) by 2DE-MS. Proteins. 2004;55:229–235. doi: 10.1002/prot.10640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.