Abstract

Caspase-2 is an initiator caspase, which has been implicated to function in apoptotic and non-apoptotic signalling pathways, including cell-cycle regulation, DNA-damage signalling and tumour suppression. We previously demonstrated that caspase-2 deficiency enhances E1A/Ras oncogene-induced cell transformation and augments lymphomagenesis in the EμMyc mouse model. Caspase-2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (casp2−/− MEFs) show aberrant cell-cycle checkpoint regulation and a defective apoptotic response following DNA damage. Disruption of cell-cycle checkpoints often leads to genomic instability (GIN), which is a common phenotype of cancer cells and can contribute to cellular transformation. Here we show that caspase-2 deficiency results in increased DNA damage and GIN in proliferating cells. Casp2−/− MEFs readily escape senescence in culture and exhibit increased micronuclei formation and sustained DNA damage during cell culture and following γ-irradiation. Metaphase analyses demonstrated that a lack of caspase-2 is associated with increased aneuploidy in both MEFs and in EμMyc lymphoma cells. In addition, casp2−/− MEFs and lymphoma cells exhibit significantly decreased telomere length. We also noted that loss of caspase-2 leads to defective p53-mediated signalling and decreased trans-activation of p53 target genes upon DNA damage. Our findings suggest that loss of caspase-2 serves as a key function in maintaining genomic integrity, during cell proliferation and following DNA damage.

Keywords: caspases, DNA-damage response, cell cycle, genomic instability

Caspase-2 is the most evolutionarily conserved caspase with highest sequence similarity to Caenorhabditis elegans caspase, CED-3.1 Caspase-2 has been shown to have a role in apoptosis induced by various stimuli, including mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation,2, 3 heat shock,4 TRAIL,5 cytoskeletal damaging drugs6 and oocyte cell death.7, 8 The function of caspase-2 has, however, remained unclear as caspase-2 knockout (casp2−/−) mice have no overt phenotype and only minor apoptotic defects in some cell types.7, 9, 10 Interestingly, casp2−/− mice have an abnormal abundance of oocytes and display premature ageing-related traits indicating that caspase-2 may have context-dependent function(s).11, 12, 13 In addition to its localisation to cytosol, caspase-2 is the only caspase that localises to the nucleus.14, 15 Recent studies have demonstrated possible non-apoptotic and nonnuclear functions of caspase-2 in cell-cycle maintenance, oxidative stress response and tumour suppression.13, 16 The loss of caspase-2 has been associated with increased cell proliferation and defective cell-cycle arrest in response to irradiation.17 In addition, a role for caspase-2 in the checkpoint kinase, Chk1, inhibited ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/ATR DNA-damage response (DDR) has been suggested in p53-deficient cells.17, 18

Cell-cycle progression is tightly regulated by a series of checkpoints to safeguard against DNA damage induced by stresses such as replication, metabolism, free radicals, or by ionising radiation (IR) and cytotoxic drugs. Checkpoint activation is regulated through the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and by CDK inhibitors, including p19Arf and p16INK4a, which induce cellular senescence and have been implicated in cell immortalisation.19 Improper segregation of chromosomes during mitosis or excessive and irreparable damage to DNA induces DDR, which functions to activate cell-cycle checkpoints and lead to cellular senescence to allow DNA repair or apoptosis to remove the damaged cell.20 The activation of DDR pathway components ATM, ATR and checkpoint kinases (Chk1, Chk2) are critical for cell-cycle arrest and repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). The activation of ATM and ATR leads to the phosphorylation and activation of histone H2AX, which is recruited to the sites of DNA damage.20 This follows activation of multiple downstream targets, including Chk1, Chk2 and p53 leading to checkpoint activation and DNA repair. Activation of p53 is tightly regulated by ATM-dependent Chk2-mediated phosphorylation and stabilisation and Mdm2-ubiquitin ligase-mediated degradation.20, 21 In addition, the tumour suppressor protein, p19Arf, sequesters and inhibits Mdm2 and allows transactivation of a number of p53 target genes that control cell growth or apoptosis.22, 23

Inaccurate DNA repair or aberrant cell-cycle checkpoint surveillance results in accumulation of DNA damage and genomic or chromosome instability (CIN).20 Mutations in ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia), ATR (Seckel syndrome) and Chk2 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome) all display signs of genomic instability (GIN) and increased susceptibility to cancer.24, 25, 26 GIN and CIN commonly arise from changes in whole chromosome number (aneuploidy) and there is strong evidence that aneuploidy is important for tumour development.27 GIN precedes cellular transformation and oncogenesis and is frequently associated with loss of p53 function.28, 29 The activation of the DDR is therefore critical to maintain genome stability, but the mechanisms underlying the decision to activate DNA repair and survive or to die are not fully understood.

Given that earlier studies suggest a function for caspase-2 in cell-cycle regulation, proliferation and tumour suppression, we tested whether the deficiency of caspase-2 leads to GIN. In this study, using primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and spontaneously immortalised MEFs (iMEFs) from casp2+/+ and casp2−/− mice, we demonstrate that cells lacking caspase-2 display increased DNA damage, aneuploidy and GIN in culture. We also show that caspase-2-deficiency results in reduced p53 activation and consequently reduced p21 expression in response to DNA damage. Thus, our data show that caspase-2 is important in maintaining genome stability and provides a possible mechanistic basis for its function as a putative tumour suppressor.

Results

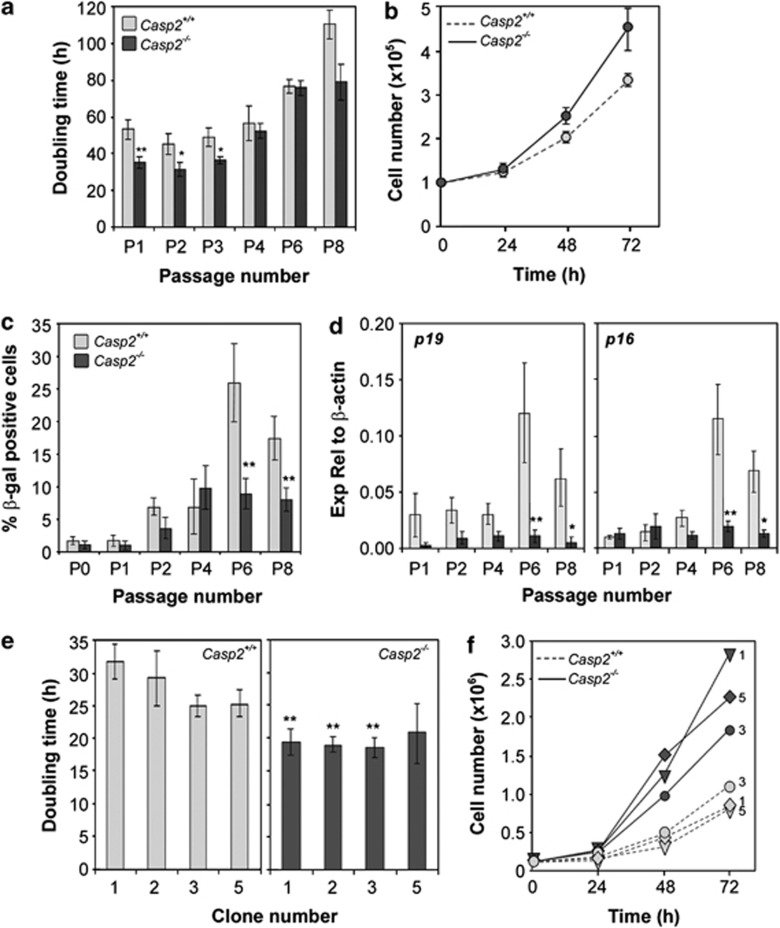

Casp2−/−MEFs are rapidly immortalised in culture

Primary MEFs are known to undergo senescence in culture.30 We assessed whether caspase-2-deficiency affects proliferative capacity and onset of senescence over serial passages in culture. We found that casp2−/− MEFs exhibit a faster population doubling time (∼25–30 h) over the first three passages compared with wild-type (casp2+/+) MEFs (45 h). Casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs both showed slowing proliferation over serial passages, with their population-doubling time increasing to 100–110 h by passage 8 (Figure 1a). The increase in doubling time in casp2+/+cells was associated with cells entering senescence by passage 6, as detected by SA-β-gal activity (Figure 1c). Interestingly, although casp2−/− MEFs also displayed slower proliferation by passage 6, there was no significant increase in the number of senescent cells at this time and no significant increase in levels of p19Arf and p16Ink4a transcript, two key senescence-induced genes,19, 31 compared with casp2+/+cells (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Caspase-2-deficient MEFs proliferate faster and escape senescence. (a) Doubling time of Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− primary MEFs following serial passaging (P1–P8). (b) Proliferation rate of early passage Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs was determined by cell viability counts at 24, 48 and 72 h. (c) Senescence was assayed by SA-β-galactosidase staining of cells at different passages. (d) Markers of cell-cycle arrest and senescence, p19Arf and p16INK4a, were assessed by qPCR. Doubling time (e) and proliferation rate (f) of iMEF clonal populations derived from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− primary MEFs. Data from primary MEFs show mean±S.E.M. from at least three different batches of MEFs. Data from iMEFs were taken from 2–3 independent experiments and show mean±S.E.M. where indicated. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

We found that casp2−/− MEFs overcome the slower doubling time observed at passage 6 more readily than casp2+/+ cells and we were able to readily isolate several casp2−/− MEF clones that had escaped senescence as a result of spontaneous immortalisation (Supplementary Figure S1).32Casp2+/+MEFs also became immortalised but at a later passage (P8). The iMEFs were characterised by their ability to be continually passaged and their faster growth rate compared with primary MEFs. The casp2−/− iMEFs again showed significantly increased proliferation rate compared with casp2+/+ iMEFs (Figures 1e and ). In addition, casp2−/− iMEFs appeared morphologically different, less fibroblastic and more rounded compared with casp2+/+ iMEFs (Supplementary Figure S1), but still exhibited contact inhibition and were unable to grow in soft agar (data not shown), indicating that they were not transformed. These findings indicate that loss of caspase-2 enhances cell proliferation and allows cells to readily overcome cellular senescence in cell culture.

Several studies have implicated caspase-2 in regulating DNA damage and cell-cycle checkpoint responses.17, 33, 34 We investigated cell-cycle checkpoint responses by phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (pH3) staining, to quantify mitotic cells, using immortalised MEFs (iMEFs and SV40-immortalised MEFs) as they showed faster proliferation rates (Figure 1f and data not shown) and could be readily arrested by γ-irradiation treatment. Both casp2+/+ and casp2−/− immortalised MEFs displayed efficient G2 arrest 4 h after IR, as indicated by the reduction in the number of pH3 positive cells (Supplementary Figure S2). Interestingly, the casp2−/− immortalised MEFs were able to overcome IR-induced G2 arrest more readily by 8 h post IR compared with casp2+/+ cells. Taken together, these findings indicate that loss of caspase-2 disrupts IR-induced G2/M checkpoint regulation.

Loss of caspase-2 results in increased DNA damage

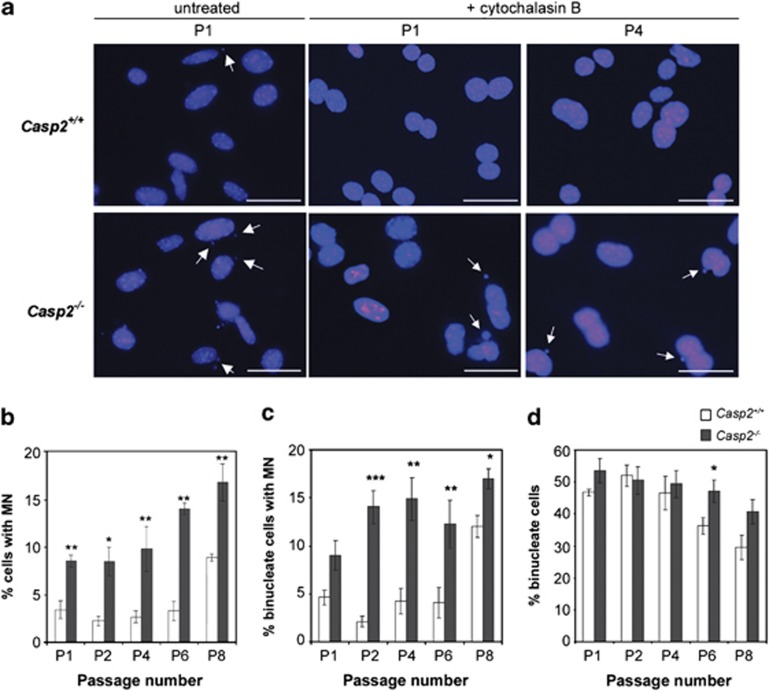

The increased proliferative capacity and increased ability to overcome replication induced senescence in casp2−/− MEFs led us to assess whether loss of caspase-2 results in increased DNA damage. We assessed the frequency of micronuclei (MN) which can originate from DNA breaks, chromosome fragments or lagging chromosomes during aberrant cell division.35 Primary casp2−/− MEFs consistently exhibited increased MN formation following serial passages compared with casp2+/+ MEFs (Figures 2a and ). We also assessed MN following cytokinesis-block (CBMN), by treating primary MEFs with cytochalasin B for 24 h to quantitate MN following a single nuclear division (Figures 2a and ). We observed a significantly higher percentage of binucleate cells with MN in both early and late passage casp2−/− MEFs compared with casp2+/+ MEFs (Figure 2c). This indicates that loss of caspase-2 leads to increased replicative DNA damage. The efficiency of cytochalasin B-induced anaphase arrest was approximately 50% as indicated by the number of binucleate cells (Figure 2d). Although the percentage of binucleated casp2+/+ cells was reduced to 25–35% at late passages (P6–P8), the casp2−/− MEFs were still 40–50% binucleate, which is another indication of the higher proliferative capacity of late passage casp2−/− MEFs (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Caspase-2-deficient MEFs exhibit increased DNA damage in culture. MN quantitated in Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs at the indicated passage number (P1, P4) in untreated and cytochalasin B-treated cells. (a) Representative images of MN in P1 and P4 MEFs ( × 40 magnification). Arrows indicate cells containing MN. Scale bar=10 μm. Quantitation of (b) total MN-containing cells and (c) binucleate cells containing MN at the indicated passage number from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs. (d) The percentage of total binucleate cells was quantitated as a measure of efficacy of cytochalasin B-induced cytokinesis arrest. At least 500 cells were counted at each passage and, for each genotype. Data indicate mean±S.E.M. and were obtained from three independent experiments in at least three independent batches of cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

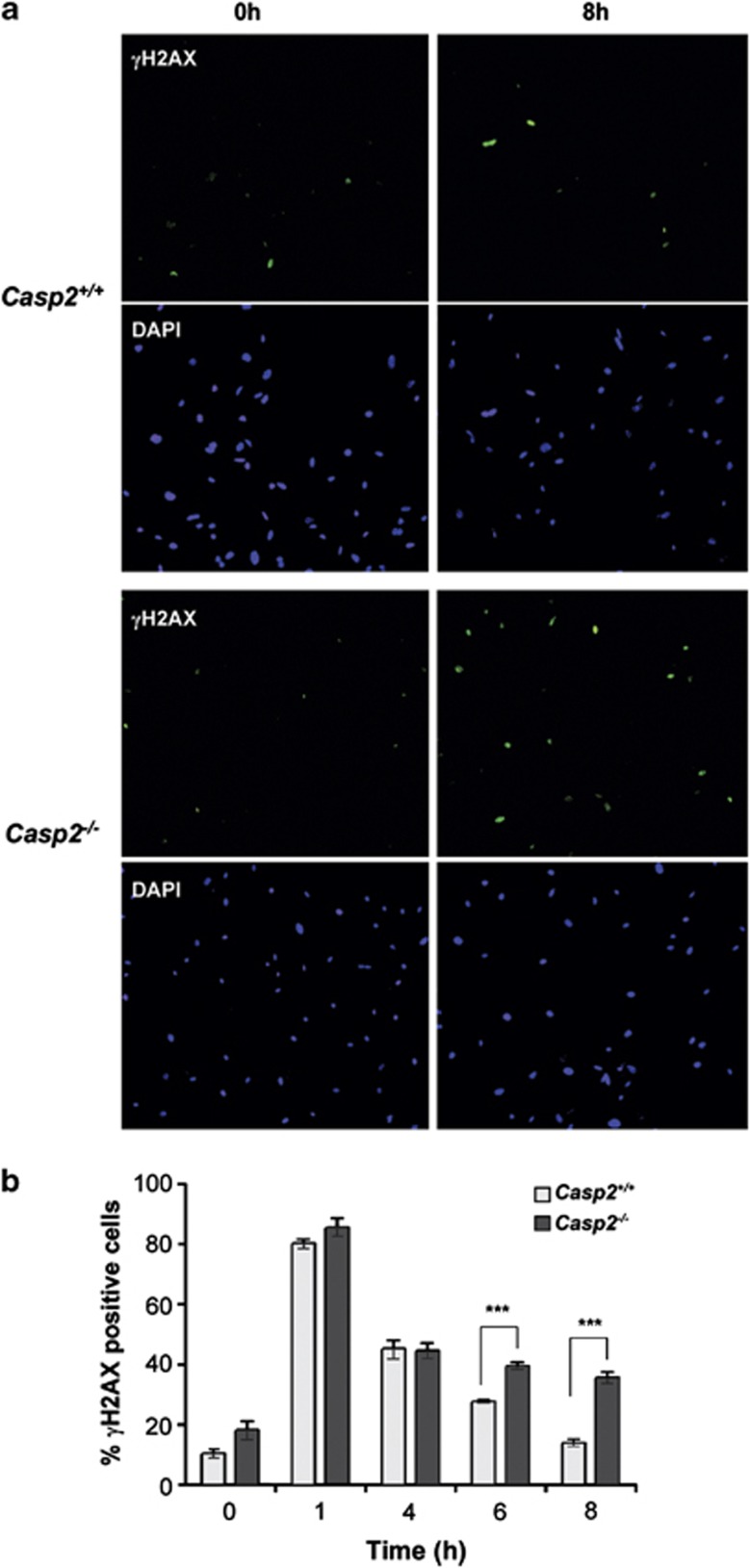

We next assessed the extent of DNA damage following IR treatment by γH2AX staining, a marker of DNA damage.36 One hour after IR (10 Gy), γH2AX levels increased significantly with 80–90% of cells showing a strong γH2AX signal (Figures 3a and ). While, the number of γH2AX positive cells decreased over time following IR, a significantly increased proportion of casp2−/− MEFs were γH2AX positive (40% at 6 h and 36% at 8 h) compared with casp2+/+ MEFs (30% at 6 h and 14% at 8 h) (Figures 3b). These observations indicate that caspase-2-deficient MEFs exhibit delayed DNA damage repair, and sustained levels of DNA damage following IR treatment.

Figure 3.

Loss of caspase-2 leads to sustained DNA damage following IR treatment. Early passage primary Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs were γ-irradiated (10 Gy) and analysed over the indicated time course. (a) Representative images of cells stained with anti-phospho-histone H2AX (Ser139) and DAPI at the indicated time points. Images were taken at 20 × magnification and are representative of four independent experiments. (b) Quantitation of γH2AX positive cells. Data are represented as mean±S.E.M. from four independent experiments (***P<0.001). For each experiment, at least 300 cells were scored per sample

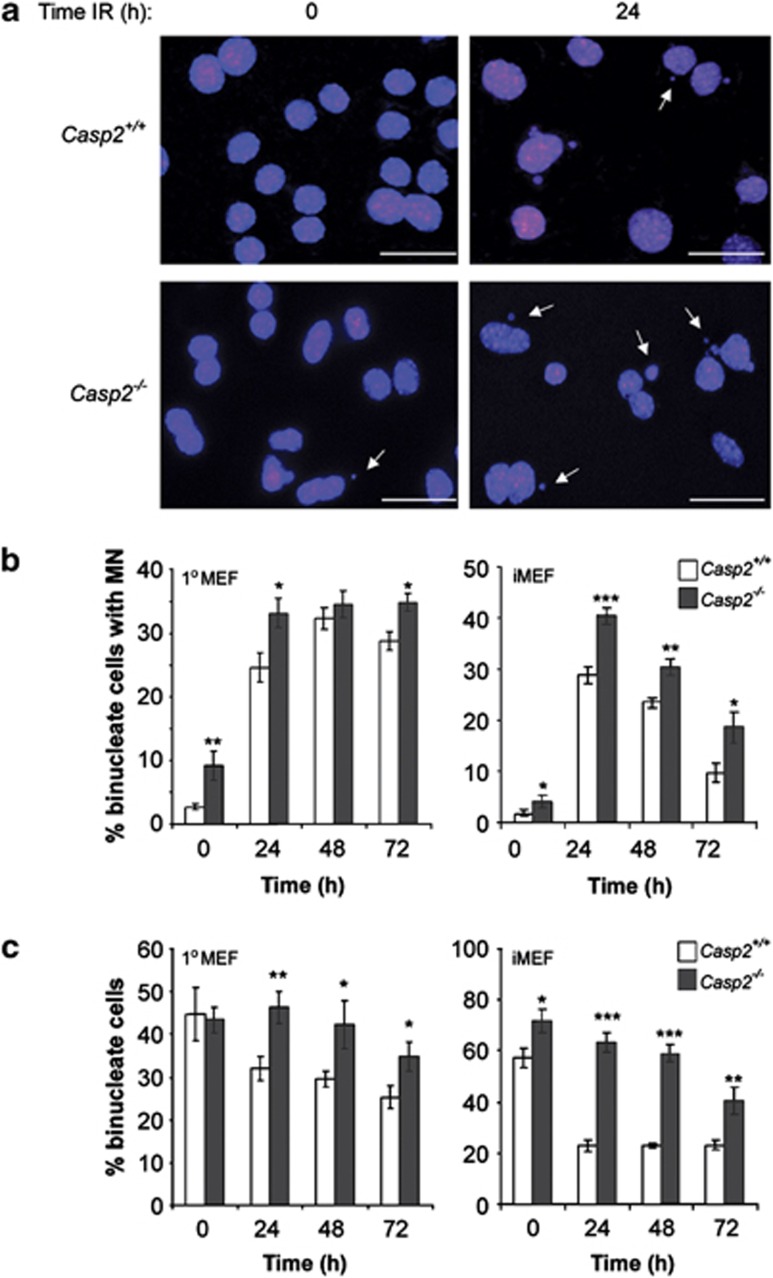

We further assessed this persistent DNA damage over a longer time period using the CBMN assay. As expected, casp2−/− MEFs displayed a significantly higher percentage of binucleated cells with MN compared with casp2+/+ MEFs 24 h after γ-radiation and this was sustained up to 72 h after treatment (Figures 4a and ). We observed a similar result in casp2−/− iMEFs that displayed a more pronounced increase in IR-induced MN (Figure 4b). We also noted that casp2−/− MEFs exhibited a significant increase in the number of binucleate cells at all time points compared with casp2+/+ cells (Figure 4c), which further demonstrates the ability of casp2−/− cells to proliferate faster and overcome irradiation-induced cell-cycle arrest (Supplementary Figure S2). The presence of MN suggest that casp2−/− cells more frequently enter mitosis with damaged DNA, leading to GIN.

Figure 4.

Increased MN in caspase-2-deficient cells following IR treatment. Cells were treated with low dose γ-radiation (5 Gy) and DNA damage assessed by CBMN assay following 24, 48 and 72 h after IR-induced damage. (a) Representative images of DAPI stained cells with arrows showing binucleated cells containing MN (40 × magnification). Scale bars=10 μm. (b) Percentage of binucleated cells with MN as determined by microscopy of primary MEFs (1° MEF) and iMEFs. (c) The total number of binucleated cells observed was quantitated following IR treatment in primary and iMEFs. Note the significant increase in percentage binucleated cells in Casp2−/− cells indicating their ability to escape IR-induced cell-cycle arrest. At least 500 cells were counted per time point for each genotype. Values are mean±S.E.M. and are representative of three independent experiments in at least three independent batches of cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Caspase-2 deficiency enhances aneuploidy

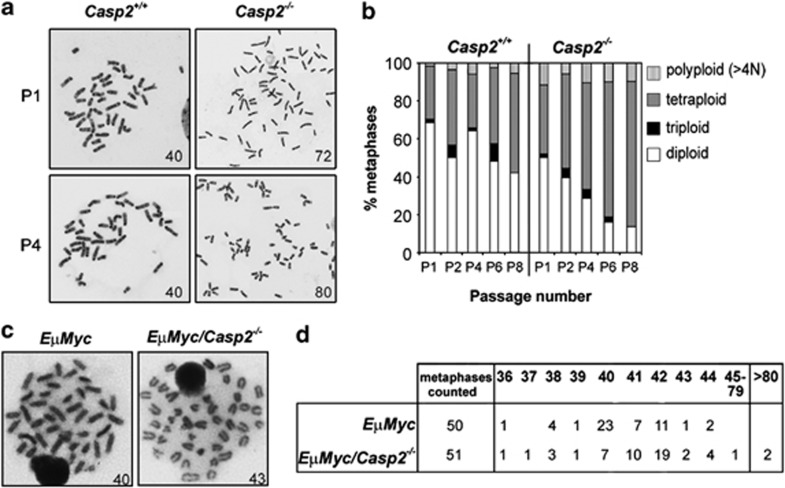

Aberrant proliferation and mitotic checkpoint control, as well as abnormalities in DSB repair leading to accumulative DNA damage are all common causes of CIN. Given the increased proliferation rate and increased DNA damage observed in casp2−/− MEFs, we further investigated GIN caused by loss of caspase-2. Analysis of metaphase chromosome spreads from serially passaged MEFs demonstrated an increased frequency of aneuploidy in casp2−/− MEFs (Figures 5a and ). Cells with diploid chromosome number (40) were observed in approximately 70% of casp2+/+ P1 MEFs compared with only 50% in casp2−/− P1 MEFs (Figure 5b). A significant reduction in the number of diploid cells was observed in casp2−/− MEFs by passage 4 (30%) with a corresponding increase in the number of tetraploid cells (55%) compared with casp2+/+ P4 MEFs (65% diploid and 30% tetraploid). In addition, casp2−/− MEFs displayed a higher frequency of polyploidy (>4N) compared with casp2+/+ MEFs at each passage (Figure 5b). Given that loss of caspase-2 enhances EμMyc-induced lymphomagenesis,17 we also assessed ploidy in caspase-2-deficient EμMyc tumours. Analysis of metaphases from lymphoma cells derived from both EμMyc and EμMyc/casp2−/− mice demonstrated that the majority of tumour types were diploid (40 chromosomes, n=50), however, there was an increased number of aneuploid cells in EμMyc/casp2−/− lymphomas with a significant number of these tumours displaying gain of chromosome number (>40) (Figures 5c and ). These data indicate that loss of caspase-2 increases tumour aneuploidy in vivo.

Figure 5.

Caspase-2-deficient cells exhibit aneuploidy. Metaphase analysis of Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs and of lymphoma cells from EμMyc or EμMyc/Casp2−/− mice. (a) Images of metaphase spreads from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− early (P1) and late (P4) passages MEFs, with chromosome number indicated. Casp2−/− MEF chromosome images are shown at lower magnification to visualise level of aneuploidy. (b) Quantitation of near diploid, near triploid, near tetraploid and polyploid (>4N) metaphases from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs at the indicated passage number. Values represent mean number of metaphases showing ploidy, from three independent batches of MEFs. (c) Images of chromosomes from EμMyc and EμMyc/Casp2−/− lymphoma cells with chromosome number indicated. (d) Table indicating chromosome number from EμMyc and EμMyc/Casp2−/− lymphoma cells showing increased aneuploidy in caspase-2 deficient tumour cells

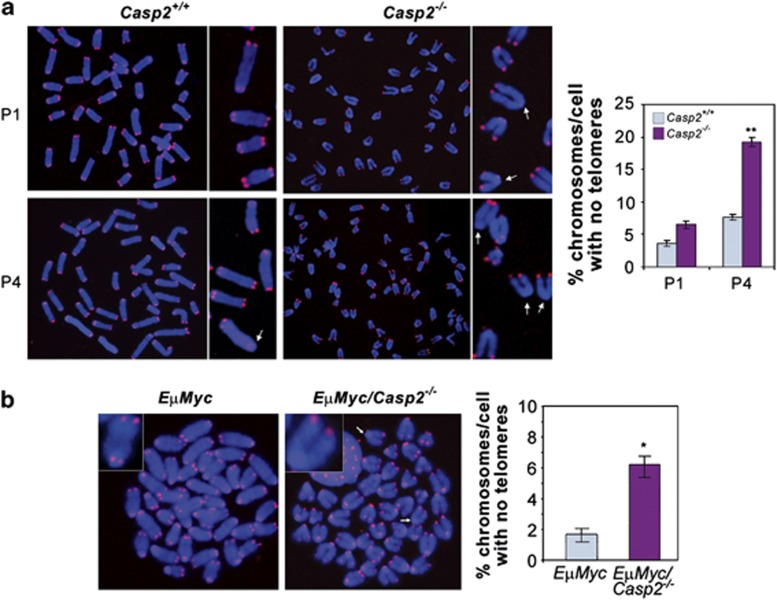

To investigate whether the increased ploidy observed in the caspase-2-deficient cells was associated with increased chromosomal breaks, we visualised chromosome ends by telomere FISH using the telomere probe PNA-Cy5. Although we did not observe any significant differences in the frequency of chromosomal breaks in casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs (data not shown), we found that late passage casp2−/− MEFs exhibited a decrease in telomere staining of a significantly higher number of chromosomes per cell (Figure 6a). There was also no evidence of chromosomal breaks in lymphoma cells, but again we noted a significant increase in the number of chromosomes that displayed decreased telomere fluorescence in EμMyc/casp2−/− lymphomas, which is directly associated with loss of telomere length (Figure 6b). These findings provide evidence for a role of caspase-2 in maintenance of telomere length and genomic stability.

Figure 6.

Loss of caspase-2 leads to telomere shortening. Telomere FISH of metaphase spreads from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs (a) or from EμMyc and EμMyc/Casp2−/− lymphoma cells (b) stained with PNA-Cy5 to label telomeres (20 × magnification). Inset images show close up of telomere staining of chromosomes, with arrows indicating loss of telomere staining. Casp2−/− MEFs consistently showed increased aneuploidy so chromosome images are shown at lower magnification. The percentage chromosomes per cell with absent telomeres was quantitated and displayed as mean±S.E.M. from three independent batches of MEFs or from three different lymphoma samples. *P<0.05

Loss of caspase-2 attenuates p53 signalling

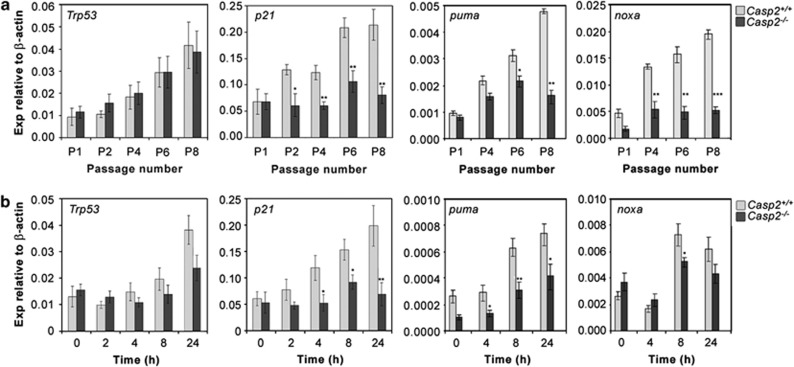

Increased proliferative capacity, decreased senescence and GIN have all been associated with loss of p53 function.28 We examined the levels of Trp53 and its transcriptional targets by quantitative PCR in casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs over serial passages in culture. Although the levels of Trp53 transcript were increased in progressively passaged MEFs, there was no significant difference between casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs (Figure 7a). We found that the transactivation of the p53 target gene, p21 was significantly impaired in casp2−/− MEFs compared with the casp2+/+ MEFs as we had observed previously (Figure 7a).17 In addition, the transcript levels of the p53 target genes involved in apoptosis, puma and noxa, were lower, indicating a general defect in p53 signalling in casp2−/− cells (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Defective transactivation of p53 targets in Caspase-2-deficient MEFs. Quantitative PCR analysis of Trp53, p21, puma and noxa transcripts from Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs cultured over 8 passages (a) or from MEFs treated with γ-radiation over 24 h time course as indicated (b). Relative expression (Exp) was determined using β-actin gene expression as a control. Data were obtained from at least three independent batches of MEFs and show mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

We next assessed the levels of Trp53 transcript, following IR-induced DNA damage in casp2−/− MEFs. Trp53 transcript levels increased following irradiation of casp2+/+ cells, and were significantly lower at 24 h in casp2−/− (Figure 7b). In addition, the transactivation of p21 and puma was significantly attenuated in casp2−/− MEFs following IR, whereas noxa expression was similar in both casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs (Figure 7b), indicating that there may be differential regulation of p53 target genes in casp2−/− MEFs. These findings further demonstrate that loss of caspase-2 affects p53-mediated DDR following IR.

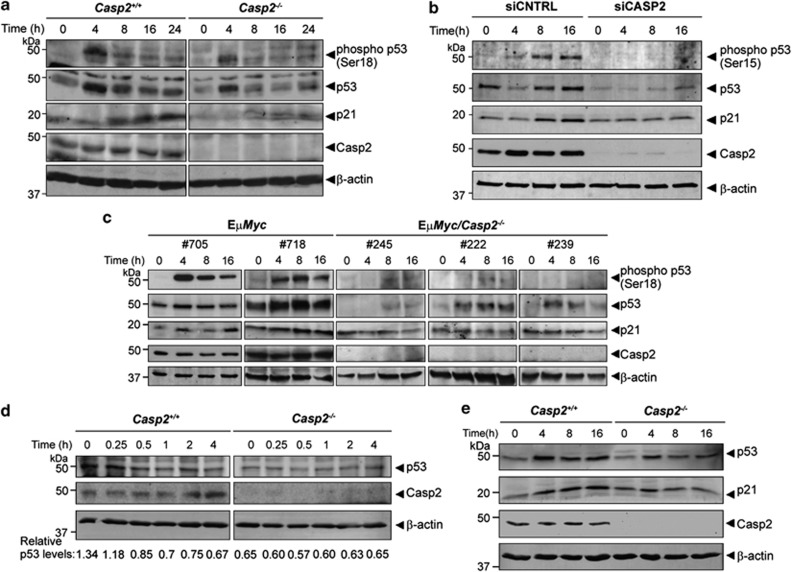

To investigate the levels and activation of p53 protein, we carried out immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated p53 (Ser18). Although total p53 protein levels increased by 4 h in both casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs, there was a marked reduction in p53 protein induction following IR (10 Gy) in casp2−/− MEFs (Figure 8a). Similarly, there was a significant reduction in the levels of phophorylated p53 (Ser18) and p21 levels in caspase-2 -deficient cells compared with casp2+/+ MEFs (Figure 8a). We also observed a marked reduction in IR-induced p53 activation and reduced p21 protein levels in casp2−/− iMEFs (data not shown). Re-expression of Casp2-GFP was able to restore p53 activation and p21 protein induction in casp2−/− MEFs following IR (Supplementary Figure S3a).

Figure 8.

Loss of caspase-2 leads to reduced p53 activity following γ-irradiation. (a) Immunoblot blot analysis of phospho-p53 (Ser18), total p53 and p21 protein levels in Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs following IR treatment (10 Gy). (b) U2OS cells treated with mock (CNTRL) siRNA or caspase-2 (CASP2) siRNA were γ-irradiated (10 Gy) and protein levels of phospho-p53 (Ser15), p53 and p21 assessed by immunoblotting. Efficiency of caspase-2 knockdown was >90%. β-actin protein levels indicate protein-loading control. (c) Phospho-p53 (Ser18), total p53 and p21 protein levels in EμMyc and EμMyc/Casp2−/− lymphoma cells following IR. (d) Loss of caspase-2 does not affect p53 turn over. Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− MEFs were treated with IR (10 Gy) for 4 h and p53 protein assessed at the indicated time points after addition of cycloheximide. (e) Casp2+/+ and Casp2−/− primary MEFs were treated with the MDM2 antagonist, Nutlin-3a (10 μM) for the indicated times. p53 and p21 protein levels were analysed by immunoblotting. β-actin is included as a loading control

As p21 protein and transcript expression can also be regulated independently of p53,37 we transfected MEFs with a stabilised p53 (Δ13–59) construct to determine whether the decreased p21 was p53-dependent. We found that expression of p53 resulted in increased p21 protein levels in casp2−/− MEFs (Supplementary Figure S3b). This further indicates that the decreased p21 protein induction is caused by reduced p53 function in casp2−/− MEFs. It should be noted that we cannot rule out possible increases in p53 activation caused by apoptosis induced by over-expression of both caspase-2 and p53 in our assays.

We further assessed the p53-mediated DDR in lymphoma cells from EμMyc and EμMyc/casp2−/− mice. Interestingly, EμMyc/casp2−/− lymphoma cells also showed significantly reduced or absent phospho-p53 levels and reduced induction of p21 protein compared with EμMyc lymphoma cells (Figure 8c). This further supports a function for caspase-2 in regulating p53 activation and indicates that reduced p53 function may contribute to the enhanced tumourigenesis in caspase-2-deficient EμMyc mice.

To confirm if a defective p53 response is specifically due to the absence of caspase-2, we assessed p53 and p21 protein levels following siRNA-mediated knockdown of caspase-2 in U2OS cells, which carry wild-type p53. We consistently achieved >90% knockdown of caspase-2 in U2OS cells (Figure 8b). Caspase-2 depleted U2OS cells also showed significantly reduced levels of total p53 protein, phospho-p53 (Ser15) and p21 levels following IR (Figure 8b).

The observed reduction in total p53 levels and activity indicates that caspase-2 may function by regulating p53 activity by affecting protein stability. We therefore assessed p53 stability in casp2−/− MEFs, by a cycloheximide chase following 4 h IR treatment, a time when we observe maximal induction of p53 (Figure 8a). Although p53 protein levels decreased in casp2+/+ MEFs by 30 min, we did not observe any significant reduction in p53 levels in casp2−/− MEF during this time period (Figure 8d). Re-expression of wild-type caspase-2 could partly restore p53 levels 4 h after IR, but did not appear to affect p53 turnover (Supplementary Figure S4). In further experiments we used Nutlin-3a, which inhibits the interaction between Mdm2 and p53, and thus enhances p53 stability. Interestingly, we found that Nutlin-3a treatment did not restore the levels of IR-induced p53 protein in casp2−/− MEFs, indicating that the effect of caspase-2 on p53 regulation may be independent of Mdm2 (Figure 8e). Together these findings indicate that caspase-2 is required for p53 activation and signalling during DDR, and the impairment of p53 activity in caspase-2-deficient cells may, at least in part, be responsible for the observed increase in DNA damage, and aneuploidy.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that loss of caspase-2 leads to increased genetic instability in MEFs and in EμMyc tumour cells. In addition, caspase-2 deficiency leads to defective p53 signalling following IR-induced DNA damage. These findings explain, at least in part, how loss of caspase-2 may lead to an increased propensity for oncogene-mediated transformation.17 We have shown that casp2−/− MEFs are readily immortalised in culture and that immortalised caspase-2-deficient MEFs show a checkpoint defect following IR. Previous reports have also implicated a role for caspase-2 in cell-cycle checkpoint regulation.17 As a consequence, casp2−/− MEFs accumulate more replicative stress-induced DNA damage, which can manifest as increased aneuploidy. These observations are consistent with a non-apoptotic function of caspase-2 in fine-tuning of the stress response.

Casp2−/− MEFs display a significantly higher level of DNA damage as indicated by the increased presence of MN and γH2AX foci compared with casp2+/+ MEFs over time in culture and following IR. γH2AX recruitment to DNA DSB is important for initiating DNA repair and removal of γH2AX is necessary for cell-cycle progression.38 We have shown that loss of caspase-2 leads to defective cell-cycle checkpoint maintenance, and cells readily escape IR-induced arrest, which would lead to inefficient repair of DNA and accumulation of IR-induced DNA damage. Mitotic entry in the presence of unrepaired DNA damage can cause errors in chromosome segregation that leads to GIN and aneuploidy.35 As increased chromosomal breaks in casp2−/− MEFs in culture were not seen, it is likely that the MN observed over serial passages originate from improper chromosome separation, consistent with increased aneuploidy in casp2−/− MEFs. These findings indicate that caspase-2 function may be required to initiate an efficient response to DNA damage to prevent GIN.

We have previously shown that an absence of caspase-2 enhances the development of EμMyc induced B-cell lymphomas.17 Our studies here further show that EμMyc /casp2−/− lymphoma cells exhibit enhanced aneuploidy and GIN. The expression of activated oncogenes Ras or Myc has been shown to induce GIN.39 For example, E1A/Ras transformed p53−/− MEFs display increased GIN caused by increased ROS production.39 We have recently reported that caspase-2 deficiency leads to increased ROS and oxidative stress in old mice13 but whether this is the reason for the increased GIN in casp2−/− primary cells and tumours is unclear. Interestingly, we have shown that casp2−/− MEFs readily escape replication-induced senescence in culture and this is associated with low levels of p16INK4a and p19Arf. This, together with the increased GIN associated with loss of caspase-2, may provide a significant driving force that permits casp2−/− cells to become immortalised or transformed by oncogenes more readily.17, 39 Similarly, casp2−/− MEFs become aneuploid more readily than casp2+/+ MEFs upon co-expression of E1A and oncogenic Ras,17 indicating that oncogene-induced GIN is exacerbated in the absence of caspase-2.

Our studies, using caspase-2-deficient primary MEFs and EμMyc lymphoma cells, show that loss of caspase-2 leads to defective activation of p53 as assessed by reduced phosphorylation of p53 (Ser18) and reduced transactivation of p21 following IR indicating that caspase-2 functions to control the DNA-damage response following genotoxic stress. The reduced p53 activity observed in cells following serial population doublings and following IR may mediate the decreased sensitivity to cell-cycle arrest and increased DNA damage thereby causing GIN. Importantly, we have also observed that loss of caspase-2 leads to reduced IR-mediated p53 activation and p21 induction in EμMyc lymphoma cells. We further noted a reduced frequency of p53 mutations in many EμMyc/casp2−/− lymphomas, compared with EμMyc lymphomas (data not shown). These findings place caspase-2 function upstream of p53, which would alleviate the selective pressure for p53 inactivation in tumours.

A recent study reported reduced p21 protein levels, but not the transcript, following depletion of caspase-2 by siRNA in IR-treated HCT116 cells.33 Consistent with this, we also observed reduced p21 protein levels in caspase-2 siRNA-depleted U2OS cells following IR, without significant changes in transcript levels (data not shown). These findings are consistent with another recent report implicating caspase-2 in post-transcriptional regulation of p21.34 In contrast, in casp2−/− MEFs, we observed both reduced p21 transcript and protein levels. The discrepancy between casp2−/− MEFs and acute knockdown of caspase-2 in cell lines may be due to cell-type specific variations in the p53-response and the nature and extent of DNA damage, which is highly dependent on the proliferative capacity of the cells. Despite this apparent disparity, the data indicate that caspase-2 has a role in regulating the DNA-damage response via p53 activation and function.

A recent in vitro study has found that caspase-2 cleaves Mdm2.40 This cleavage results in removal of the C-terminal RING, the domain required for p53 ubiquitination and this promotes p53 stability. Thus, according to this model, following DNA damage, caspase-2 has a role in a positive feedback loop that inhibits Mdm2, enhancing p53 stability and activity. While consistent with our observations of reduced p53 function in caspase-2-deficient cells, our Nutlin-3a experiments indicate that caspase-2 may regulate p53 in an Mdm2-independent manner. Further work is required to delineate and fully understand the mechanism of p53 regulation by caspase-2.

The inactivation of both p16INK4a/pRB and p19ARF/p53 pathways have been associated with the onset of tumourigenesis.28, 31 In particular, loss of p53 is associated with decreased telomere length and an increased propensity for aneuploid cells to transform.28 Interestingly, casp2−/− mice do not develop spontaneous tumours with age and we do not observe increased thymoma development following repeated low dose IR treatment of mice (unpublished data). This suggests that there may be other limiting factors in aneuploidy-induced tumourigenesis29 and the function of caspase-2 as a tumour suppressor may become important only following oncogenic stress. Although caspase-2-deficient MEFs display reduced telomere length and reduced p53 activation following DNA damage, we do not detect a complete loss of p53 function. Following oncogenic stress, decreased p53 function in casp2−/− cells would enhance survival of aneuploid cells and augment oncogene-induced chromosomal damage by allowing DNA damage to persist unchecked. Together, this would facilitate increased cellular transformation by E1A/Ras or c-Myc oncogenes and increase the ability of transformed cells to become tumourigenic.17

Our findings thus provide evidence that loss of caspase-2 results in a defective DNA-damage response and as a consequence, cells lacking caspase-2 accumulate DSBs and display chromosome aberrations and aneuploidy. These findings provide direct evidence that caspase-2 has a crucial role in the maintenance of chromosome stability, partly via regulating p53 function. Our data suggest that caspase-2 may function by fine tuning key tumour suppressor networks and has an important role in eliminating cells with genetic aberrations thereby preventing cellular transformation and oncogenesis. The fundamental question remains as to whether caspase-2 regulates p53 by directly targeting Mdm2 in vivo or whether caspase-2 indirectly regulates p53 through other tumour suppressor proteins (i.e. p19, p16) or oncogenes (Ras, Myc).17

Methods

Animal studies

Caspase–2 knockout mice (originally from Professor David Vaux, WEHI, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) have been described previously.9, 17 All animals were housed and treated in accordance with protocols approved by the SA Pathology / Central Northern Health Services Animal Ethics Committee. All mice were re-derived at our animal resource facility. EμMyc transgenic and EμMyc transgenic/casp2−/− mice have been described previously.17 EμMyc transgenic and EμMyc transgenic/casp2−/− mice were monitored daily for tumour development and lymph nodes were extracted once tumours were palpable.

Cell culture

Primary MEFs were derived from wild-type and casp2−/− embryos at day 13.5 as previously described.6, 17 Cells at the time of seeding were labelled as passage 0 (P0). MEFs were grown and maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with 0.2 mM ℒ-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), 15 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, JHR Biosciences, Brooklyn, VIC, Australia) and supplemented with 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Amersham Biosciences, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), non-essential amino-acid mix (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μM penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 10% CO2. MEFs at passage 1–3 (P1–P3) were used unless otherwise indicated and at least three independently generated MEF lines per genotype were used. iMEFs were generated by serial passaging of MEFs in culture, using the 3T3 subculture method.32 Late passage MEFs (P6–P8) that were able to overcome senescence and formed colonies were expanded and termed immortalised. At least three individual cell clones from two independent MEF lines were assessed in all experiments.

Lymphoma cells from EμMyc transgenic and EμMyc/casp2−/− mice were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and 100 μM asparagine in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 10% CO2. U2OS cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 15 mM HEPES in the presence of 100 μM penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation of casp2+/+ and casp2−/− MEFs was assayed by doubling time experiments. For population doubling times, primary MEFs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells and iMEFs seeded at 1 × 104 cells in a 60 mm dish at Day 0. Cells were harvested by trypsinisation every 24 h for 3 days and number of viable cells estimated by trypan blue exclusion. For DNA-damage analysis cells were treated with gamma radiation at 5 Gy or 10 Gy using a 137Cs source.

Cytogenetic analysis

Colcemid (20 ng/ml) (GIBCO Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) was added to MEFs 4 h before harvesting by trypsinisation. Cells were swollen in hypotonic solution (0.075 M KCl) for 30 min at 37 °C and fixed in fresh, ice cold Carnoy's fixative (methanol:glacial acetic acid at 3 : 1) for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were spun down at 1000 r.p.m. for 10 min, and washed three times in Carnoy's fixative and then dropped onto wet glass slides, air dried and placed in a 60 °C oven overnight. Cells were either stained with 4% Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich), or were treated with 2XSSC (300 mM NaCl, 30 mM trisodium citrate) at 60 °C for 1.5 h, washed in sterile water, briefly trypsin digested for 10 sec and stained with 20% Leishman's stain (pH 6.8) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 min. Metaphase spreads were assessed and counted by SA Pathology Cytogenetics Facility (Adelaide, SA, Australia). FISH analysis of chromosome breaks was performed using the Telomere PNA FISH kit/Cy3 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Chromosomes were co-stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Fluorescent chromosome images were captured using an epifluorescence microscope (model BX51; Olympus, Munster, Germany) and camera (UCMAD3/CVM300, Olympus). Cells were visualised under × 40 or × 100 ULAPO objective lens with NA=1.5. Images were processed using Olysia BioReport Software (Olympus) and manually merged using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 software (San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in 25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% nonyl phenoxylpolyethoxylethanol (NP-40, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA), 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodiumdodecyl sulphate (SDS, Sigma-Aldrich), in the presence of protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). 20–50 μg total protein in SDS protein buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 200 mM dithiothreitol, 4% SDS , 0.2% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol) was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk-TBST (Tris Buffered saline in 0.05% Tween20) and incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-phospho p53 (Ser15) rabbit antibody (1 : 1000 dilution, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), 0.4 μg/ml anti-p53 mouse antibody (clone IC12 , Cell signaling or DO-1, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), 0.4 μg/ml anti-p21 mouse antibody (clone F5, Santa Cruz and clone SX118, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 1 μg/ml anti-caspase-2 rat antibody (11B4, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), 1 μg/ml β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (AC15, Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were detected by enhanced chemifluorescence or enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL-Plus, Amersham/Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Primary MEFs (1 × 105) were seeded onto glass cover slips before exposure to γ-radiation (10 Gy). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4 °C, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100/PBS for 10 min. Cells were incubated with anti-phospho histone H2AX (Ser139) (Cell Signaling) at 1 : 50 dilution in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C, followed by addition of donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, CA, USA) (1 : 1000 in blocking solution) and then counterstained with 2 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Roche) for 5 min. Cover slips were mounted onto glass slides with ProLong Gold Antifade reagent (Molecular Probes). Fluorescent images were captured using an epifluorescence microscope as above. At least 300 cells were scored in each experiment for each sample.

Micronucleus assay

Cells were seeded onto coverslips, and left untreated or γ-irradiated (5–10 Gy) and incubated for 24, 48 or 72 h. Cells were also treated with 4 μg/ml cytochalasin B (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated a further 24 h before fixation in methanol:glacial acetic acid mix (3 : 1). Cells were stained with 2 μg/ml DAPI (Roche) for 5 min and MN visualised by on an epifluorescence microscope (model BX51; Olympus) at × 40 and × 100 magnification as above. At least 500–1000 cells were counted per slide.

Senescence associated β-gal staining

Senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (Cell Signaling) was used to identify senescent cells. Briefly, cells were fixed for 10 min and then rinsed thoroughly in PBS and incubated with the X-gal staining solution for 30 min at 37 °C. The stained cells were washed with PBS and mounted in glycerol.

Transfections and siRNA

Casp2-GFP construct and a vector control (pEGFP-N1) (2 μg each) were transfected into casp2+/+ or casp2−/− MEFs using Lipofectamine LTX and PLUS reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). P53 (Δ13–59) expression construct was kindly provided by Dr. Ygal Haupt (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Cells were incubated with the transfection complexes for 16 h and then treated with IR for the indicated times before harvesting for protein analysis. siRNAs were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma (Shanghai, China): control siRNA (5′-UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUACTT-3′); human caspase-2 siRNA (position #102)(5′ GUUGUUGAGCGAAUUGUUATT-3′). U2OS cells (3 × 105) were transfected with siRNAs (50 nM) in Opti-MEM (Sigma-Aldrich) using TransIT-TKO siRNA transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 30 h, media was replaced and cells were allowed to recover for 16 h before γ-irradiation (10 Gy) from a 137Cs source.

Quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from MEFs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA synthesised using oligo-dT primers, and High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research, Mortlake, NSW, Australia) using RT2 Real-Time SYBR Green/ROX PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The following primer sets were used for the amplification of mouse genes in qPCR reactions: p21, 5′-AGTGTGCCGTTGTCTCTTCG-3′, 5′-ACACCAGAGTGCAAGACAGC-3′ Trp53, 5′-CTCACTCCAGCTACCTGAAGA-3′, 5′-AGAGGCAGTCAGTCAGTCTGAGTCA-3′ puma, 5′-ATGCCTGCCTCACCTTCATCT-3′, 5′-AGCACAGGATTCACAGTCTGGA-3′ noxa, 5′-ACTGTGGTTCTGGCGCAGAT-3′, 5′-TTGAGCACACTCGTCCTTCAA-3′ β-actin: 5′-TGTTTGAGACCTTCAACACC-3′, 5′-TAGGAGCCAGAGCAGTAATC-3′.

Reactions were performed in triplicate and the mRNA expression levels normalised against the internal control gene β-actin using the 2−▵▵CT method.

Protein stability assays

For cycloheximide chase analysis, casp2+/+ and casp2−/− primary MEFs were grown in 60-mm dishes, irradiated (10 Gy) for 3–4 h and then treated with cyclohexomide (20 μg/ml). Cells were harvested at the indicated times over a 4-h time course and proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. The MDM2 antagonist, Nutlin-3a (10 μM) (Cayman Biochemicals, Denver, CO, USA) was added to MEFs and cells harvested at the indicated times following treatment and analysed for p53 protein levels.

Statistical analysis of data

Student's t-test was used for all data analysis unless otherwise stated. Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Vaux, Ygal Haupt, Andreas Villunger and Paul Neilson for providing various reagents, and staff of the SA Pathology animal resource facility for help in maintaining the mouse strains. We thank members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant (626905), a South Australian Cancer Collaborative Fellowship to LD and a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1002863) to SK.

Glossary

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related

- CBMN

cytokinesis block micronuclei

- CIN

chromosome instability

- DDR

DNA-damage response

- DSB

double-strand breaks

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridisation

- GIN

genomic instability

- IR

ionising radiation

- MEF

murine embryonic fibroblasts

- MN

micronuclei

- MOMP

mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- iMEF

immortalised MEF

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by G Melino

Supplementary Material

References

- Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Induction of apoptosis by the mouse Nedd2 gene, which encodes a protein similar to the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell death gene ced-3 and the mammalian IL-1 beta-converting enzyme. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassus P, Opitz-Araya X, Lazebnik Y. Requirement for caspase-2 in stress-induced apoptosis before mitochondrial permeabilization. Science. 2002;297:1352–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1074721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JD, Enoksson M, Suomela M, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Caspase-2 acts upstream of mitochondria to promote cytochrome c release during etoposide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29803–29809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonzon C, Bouchier-Hayes L, Pagliari LJ, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. Caspase-2-induced apoptosis requires bid cleavage: a physiological role for bid in heat shock-induced death. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2150–2157. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Lee Y, Kim W, Ko H, Choi H, Kim K. Caspase-2 primes cancer cells for TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by processing procaspase-8. EMBO J. 2005;24:3532–3542. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LH, Read SH, Dorstyn L, Lambrusco L, Kumar S. Caspase-2 is required for cell death induced by cytoskeletal disruption. Oncogene. 2008;27:3393–3404. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron L, Perez GI, Macdonald G, Shi L, Sun Y, Jurisicova A, et al. Defects in regulation of apoptosis in caspase-2-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1304–1314. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt LK, Margolis SS, Jensen M, Herman CE, Dunphy WG, Rathmell JC, et al. Metabolic regulation of oocyte cell death through the CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of caspase-2. Cell. 2005;123:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly LA, Ekert P, Harvey N, Marsden V, Cullen L, Vaux DL, et al. Caspase-2 is not required for thymocyte or neuronal apoptosis even though cleavage of caspase-2 is dependent on both Apaf-1 and caspase-9. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:832–841. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden VS, Ekert PG, Van Delft M, Vaux DL, Adams JM, Strasser A. Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis and cytochrome c release can occur independently of both caspase-2 and caspase-9. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:775–780. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga M, Sinha Hikim AP, Datta S, Ferrini MG, Brown D, Kovacheva EL, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress and caspase 2-mediated intrinsic pathway signaling in age-related increase in muscle cell apoptosis in mice. Apoptosis. 2008;13:822–832. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Padalecki SS, Chaudhuri AR, De Waal E, Goins BA, Grubbs B, et al. Caspase-2 deficiency enhances aging-related traits in mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Wilson C, Puccini J, Ho L, Kumar S.Impaired antioxidant defence and accumulation of oxidative stress in caspase-2-deficient mice Cell Death Differ 2012. e-pub ahead of print 17 February 2012 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baliga BC, Colussi PA, Read SH, Dias MM, Jans DA, Kumar S. Role of prodomain in importin-mediated nuclear localization and activation of caspase-2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4899–4905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colussi PA, Harvey NL, Kumar S. Prodomain-dependent nuclear localization of the caspase-2 (Nedd2) precursor. A novel function for a caspase prodomain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24535–24542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Caspase 2 in apoptosis, the DNA damage response and tumour suppression: enigma no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nrc2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LH, Taylor R, Dorstyn L, Cakouros D, Bouillet P, Kumar S. A tumor suppressor function for caspase-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811928106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidi S, Sanda T, Kennedy RD, Hagen AT, Jette CA, Hoffmans R, et al. Chk1 suppresses a caspase-2 apoptotic response to DNA damage that bypasses p53, Bcl-2, and caspase-3. Cell. 2008;133:864–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnero A, Hudson JD, Price CM, Beach DH. p16INK4A and p19ARF act in overlapping pathways in cellular immortalization. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:148–155. doi: 10.1038/35004020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W, Levine AJ. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of oncoprotein Hdm2 is required for Hdm2-mediated degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3077–3080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W, Levine AJ. P19(ARF) stabilizes p53 by blocking nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of Mdm2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6937–6941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin MF. Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:759–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimprich KA, Cortez D. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:616–627. doi: 10.1038/nrm2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott KW. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:619–631. doi: 10.1038/nrg2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Boveri revisited: chromosomal instability, aneuploidy and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:478–487. doi: 10.1038/nrm2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini R, Mak TW, Melino G. The impact of p53 and p73 on aneuploidy and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fang X, Baker DJ, Guo L, Gao X, Wei Z, et al. The ATM-p53 pathway suppresses aneuploidy-induced tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14188–14193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005960107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–747. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringold F, Serrano M. Tumor suppressors and oncogenes in cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn D, Budach W, Janicke RU. Caspase-2 is required for DNA damage-induced expression of the CDK inhibitor p21(WAF1/CIP1) Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1664–1674. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghiyev AF, Rokhlin OW, Glover RB. Caspase-2-based regulation of the androgen receptor and cell cycle in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:745–752. doi: 10.1177/1947601911426007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. Chromosomal biomarkers of genomic instability relevant to cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2002;7:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42462–42467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel AL, Radhakrishnan SK. Lost in transcription: p21 repression, mechanisms, and consequences. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3980–3985. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh MC, Kim JA, Downey M, Fillingham J, Chowdhury D, Harrison JC, et al. A phosphatase complex that dephosphorylates gammaH2AX regulates DNA damage checkpoint recovery. Nature. 2006;439:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature04384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo RA, Poon RY. Activated oncogenes promote and cooperate with chromosomal instability for neoplastic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1317–1330. doi: 10.1101/gad.1165204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver TG, Meylan E, Chang GP, Xue W, Burke JR, Humpton TJ, et al. Caspase-2-mediated cleavage of Mdm2 creates a p53-induced positive feedback loop. Mol Cell. 2011;43:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.