Abstract

Autophagy has been implicated in both cell survival and programmed cell death (PCD), and this may explain the apparently complex role of this catabolic process in tumourigenesis. Our previous studies have shown that caspases have little influence on Drosophila larval midgut PCD, whereas inhibition of autophagy severely delays midgut removal. To assess upstream signals that regulate autophagy and larval midgut degradation, we have examined the requirement of growth signalling pathways. Inhibition of the class I phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway prevents midgut growth, whereas ectopic PI3K and Ras signalling results in larger cells with decreased autophagy and delayed midgut degradation. Furthermore, premature induction of autophagy is sufficient to induce early midgut degradation. These data indicate that autophagy and the growth regulatory pathways have an important relationship during midgut PCD. Despite the roles of autophagy in both survival and death, our findings suggest that autophagy induction occurs in response to similar signals in both scenarios.

Keywords: programmed cell death, autophagy, growth signalling, Drosophila

Programmed cell death (PCD) is essential for removing excess and unwanted cells to maintain tissue homoeostasis, deleting cells damaged by pathogens or genotoxic stress, and has been implicated in diseases, including cancer and neurodegeneration. The canonical caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways are important mediators of developmental PCD. However, recent studies in many model systems suggest that some physiological cell deaths require alternative pathways, including programmed necrosis and autophagy.1, 2 One of the unique forms of cell death requiring autophagy is evident in the removal of the Drosophila larval midgut.3, 4, 5

Macroautophagy (autophagy) has roles in normal development, stress response, neurodegeneration, cell growth, PCD and cancer, and is known to promote cell survival under nutrient deprivation and stress conditions.6, 7 Under cell growth-promoting conditions, autophagy occurs at basal levels and is induced to high levels under growth-limiting conditions, such as contact inhibition, metabolic stress and nutrient limitation. Studies using transformed cells with oncogenic Ras expression have shown that a complex relationship exists between autophagy, cell growth and cell death. Activated Ras expression can promote cell growth accompanied by increased autophagy, or can result in cell death that also is accompanied by increased autophagy.8, 9 The highly conserved insulin receptor/class I phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway regulates cell and tissue growth whereby under growth conditions it promotes the activation of target of rapamycin (TOR) kinase resulting in inhibition of autophagy.10 The downregulation of PI3K activity by several tumour suppressor genes, including PTEN, TSC1 and TSC2, promotes autophagy induction.11, 12

The association between growth signalling and autophagy, where autophagy is increased in growth-inhibited cells, suggests that autophagy may be contributing to limiting cell growth. Indeed, induction of autophagy in the Drosophila fat body leads to a reduction in cell size and inhibition of autophagy results in larger cells under starvation conditions.13, 14 However, the signalling pathways that regulate autophagy have additional roles; for example, TOR affects metabolism by regulating ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis.10 Therefore, the relationship between autophagy and cell growth has been difficult to evaluate. Furthermore, the relationship between growth signalling and autophagy in cell death is poorly understood.

Although the subject of some debate, supportive evidence for the role of autophagy in developmental cell death is emerging. For example, autophagy is required for PCD in various Drosophila tissues during development.3, 15, 16, 17, 18 During Drosophila development a rise in steroid hormone triggers PCD of the obsolete larval tissues, including the midgut and salivary glands.19, 20 The steroid receptor complex regulates the transcription of several cell death genes as well as genes involved in autophagy in both salivary gland and midgut before their removal by PCD.21, 22 The removal of the salivary glands requires both the canonical apoptosis machinery19, 23, 24, 25 and autophagy.18, 26 Indeed when inhibition of both caspases and autophagy are combined, a greater block in salivary gland degradation occurs compared with inhibition of either pathway alone, which suggests they function as independent degradation pathways.18 Furthermore, maintenance of growth in the salivary glands is able to block autophagy and delay degradation, indicating that growth arrest is required before the removal of the salivary gland.18

Our previous studies have shown that loss of the canonical caspase activation pathway has no effect on midgut PCD whereas genetic inhibition of autophagy severely delays midgut removal.3 Surprisingly, inhibition of autophagy suppressed midgut PCD without affecting caspase activation or activity, suggesting that caspases alone fail to execute cell death and autophagy has an active and necessary role in midgut degradation.3, 4 However, the precise role of autophagy and the cross talk between cell growth regulatory pathways during this novel form of PCD remain unclear. Here we have examined the requirement of growth signalling in midgut degradation. We report that inhibition of the class I PI3K growth pathway prevents midgut growth. Conversely, ectopic PI3K and Ras signalling resulted in cell overgrowth with reduced autophagy and delayed midgut destruction. Furthermore, premature induction of autophagy by expression of Atg1 resulted in premature midgut degradation. Surprisingly, unlike in salivary glands, where the Hippo pathway is required for cell growth arrest, autophagy and degradation,27 this pathway was not involved in regulating midgut PCD.

Results

Premature autophagy induction leads to midgut PCD

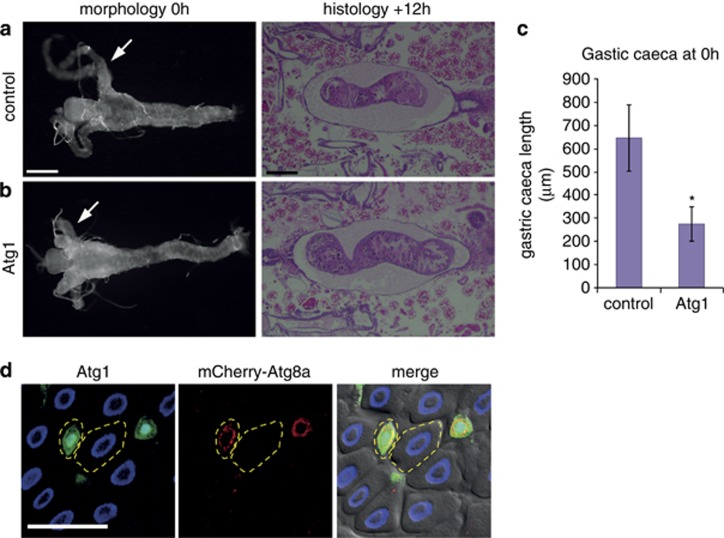

The removal of the obsolete Drosophila larval midgut requires autophagy and does not depend on the canonical caspase activation pathway.3 Given that autophagy inhibition severely delayed midgut removal, we examined if early autophagy induction, as assessed by Atg8a punta, alone was sufficient to induce premature midgut removal. The degradation of the larval midgut initiates at the end of the larval stage when the gastric caeca, present at the onset of puparium formation, begin to contract and are removed by +4 h relative puparium formation (RPF), whereas the remaining gut continues to condense (Figure 1a). Induction of autophagy by expression of Atg1 in the midgut resulted in more contracted gastric caeca, at an earlier time point as compared with the control (Figures 1a and b). Quantification of the length of gastric caeca showed a significant reduction when Atg1 was expressed compared with the control (Figure 1c). However, at later time points (+12 h RPF) once the normal induction of autophagy has initiated midgut removal appeared to occur normally (Figures 1a and b). Mosaic clones of cells overexpressing Atg1 in the midgut of feeding larvae revealed that compared with the surrounding wild-type cells, there is a high level of autophagy induction, as shown by Atg8a puncta, and smaller cell size (Figure 1d). This indicates that Atg1 expression is sufficient to induce autophagy resulting in smaller cell size.

Figure 1.

Premature induction of autophagy induces midgut PCD. Morphology of midguts at 0 h RPF (left) showing (a) control (NP1-GAL4/+) compared with (b) Atg1 overexpression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg16B/+) with premature contraction of gastric caeca (arrows). Histological analysis of paraffin sections at +12 h RPF (right) shows that at the later time point midgut contraction is similar in (a) control (NP1-GAL4/+) and (b) Atg1 overexpression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg16B/+). Scale bars in (a) represent 200 μm. (c) Quantification of the length of the gastric caeca at 0 h RPF measured with Zeiss automeasure software from control (NP1-GAL4/+) and Atg1 overexpression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg16B/+) (N=4 and 9, respectively). Quantification is average length (μm)±S.D. *P<0.001 (compared with the control). (d) Mosaic clones from feeding larvae expressing Atg1 marked by GFP (green) and DNA (blue) (hsFLP; mCherry-Atg8a/+ Act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-nlsGFP/UAS-Atg16B) have increased mCherry-Atg8a puncta (red) compared with the neighbouring cells and smaller cell size. Atg1 clone and neighbouring cell outlined. Scale bars in (d) represent 50 μm

Growth arrest is required for midgut PCD

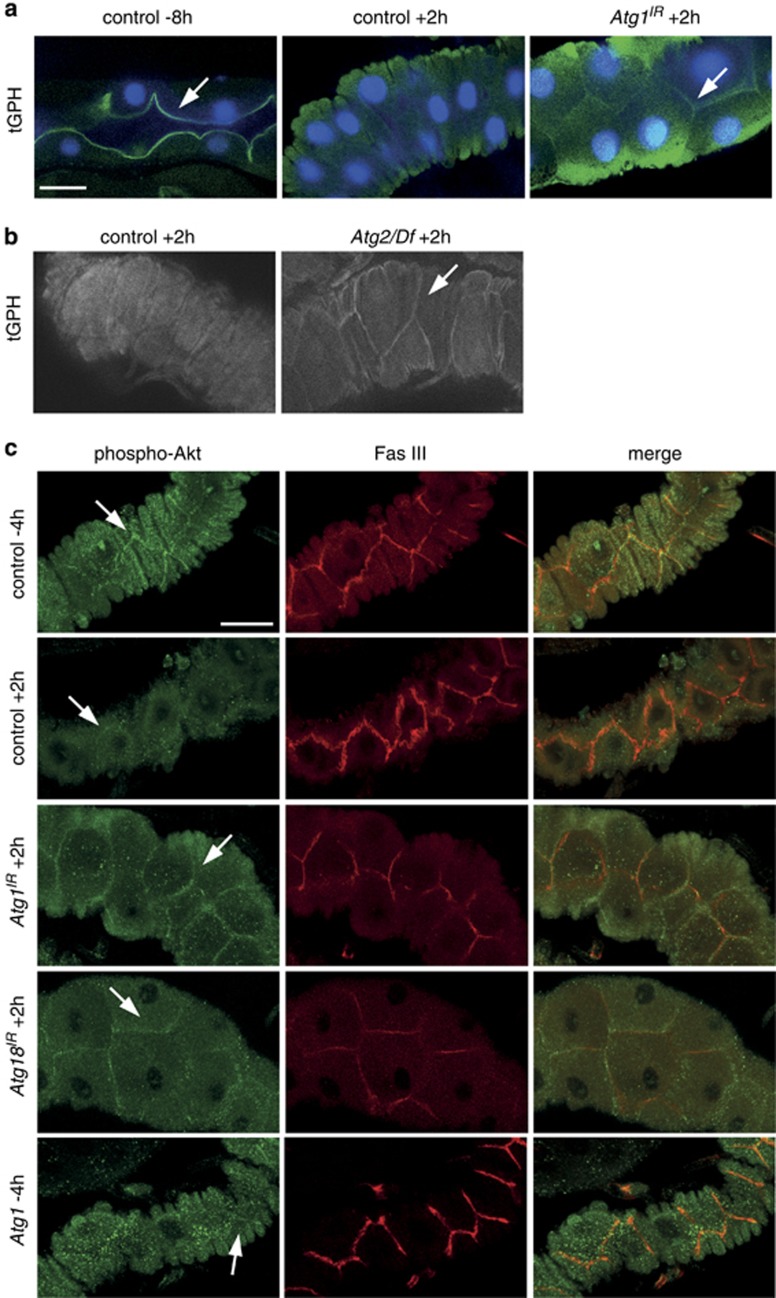

Previous studies provide evidence for an association between growth signalling and autophagy in both cell survival and during removal of the salivary glands.12, 18 To determine if this is a more widespread occurrence and in particular the importance of cell growth on PCD, we examined the relationship between growth signalling and autophagy during midgut removal. The PI3K growth signalling pathway leads to formation of phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-P3 (PIP3) on the plasma membrane and this can be assessed using the tGPH reporter (tubulin-GFP-Pleckstrin Homology).28 During active PI3K signalling tGPH is recruited to the cell cortex and following growth arrest this localization is lost. Under conditions of larval growth tGPH was localized to the cortex of gastric caeca cells and this localization was lost at +2 h RPF (Figure 2a). This indicates that growth arrest occurs in the midgut coinciding with the timing of midgut PCD.

Figure 2.

Association of growth arrest with autophagy and midgut degradation. The localization of class I PI3K activity reporters, tGPH (a and b) and phospho-Akt (c), in midguts. (a) Cortical localization of tGPH (green) and DNA (blue) in midgut from feeding larvae at −8 h RPF (left, arrow) and following puparium formation +2 h RPF (middle) tGPH is no longer localized at the cortex. Inhibition of autophagy by (a) Atg1IR knockdown (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg1IR/+) and (b) in Atg2 mutant (Atg2/Df) display cortical localization of tGPH at +2 h RPF (arrow) compared with controls. Scale bar in (a) represents 25 μm in all panels in (a) and (b). (c) Cortical localization of phospho-Akt (green, arrow) adjacent to Fasciclin III (red), a cell surface marker, in control midgut from late larvae (−4 h RPF). Following puparium formation (+2 h RPF) phospho-Akt is redistributed from the cell cortex. Inhibition of autophagy by knockdown of Atg1IR (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg1IR/+) or Atg18IR (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg18IR/+) shows persistence of cortically localized phospho-Akt at +2 h RPF (arrow). Induction of autophagy by expression of Atg1 (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg16B/+) shows decreased cortically localized phospho-Akt (arrow). Scale bar is 30 μm in all panels in (c)

To investigate the relationship between growth and autophagy we examined the effect of autophagy inhibition on growth signalling during midgut death. Important regulators of autophagy, including Atg1, Atg2 and Atg18, have previously been shown to be required for autophagy.3 Interestingly, the inhibition of autophagy, using Atg2 mutants or knockdown of Atg1 by RNAi, resulted in persistent cortical localization of tGPH in the midgut at +2 h RPF (Figures 2a and b). This implies that class I PI3K pathway signalling is no longer downregulated following puparium formation as seen in the control midgut. Another marker of PI3K activity is the localization of phosphorylated Akt to the cell cortex, owing to its interaction with PIP3, and its subsequent phosphorylation that is required for downstream signal transduction. To further investigate if autophagy inhibition by knockdown of Atg1 or Atg18 results in persistent growth signalling in the midgut we examined the localization of phosphorylated Akt, compared with the cell cortex marker Fasciclin III. In control midguts during late larval stages (−4 h RPF) phosphorylated Akt was detected at the cell cortex, and following puparium formation (+2 h RPF) this cortical localization was reduced (Figure 2c). However, in Atg1 and Atg18 RNAi midguts a significant amount of phosphorylated Akt remained at the cortex at this later stage (+2 h RPF) (Figure 2c). Before the onset of autophagy, the localization of phosphorylated Akt was similar in control and either Atg1 or Atg18 knockdown in midguts from feeding larvae (Supplementary Figure 1). We also examined the effect of autophagy induction on the localization of phosphorylated Akt. In midguts expressing Atg1 there was a reduction in cortically localized phosphorylated Akt (−4 h RPF) compared with the control (−4 h RPF) (Figure 2c). These data suggest that autophagy is required for downregulation of class I PI3K signalling and that there is a feedback regulation between autophagy and growth signalling pathways.

Maintaining growth signalling prevents autophagy and delays midgut cell death

The observation that inhibition of autophagy results in persistent class I PI3K signalling in midguts during the prepupal stage led us to investigate the requirement of upstream growth signalling on midgut degradation. Activation of the PI3K pathway in response to insulin leads to phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and its substrate, Chico, activating the catalytic subunit Dp110.29 Active Dp110 converts PIP2 to PIP3 on the plasma membrane enabling interaction with Akt and activation of the downstream effectors leading to phosphorylation of TOR kinase that stimulates cell growth and negatively regulates autophagy.29

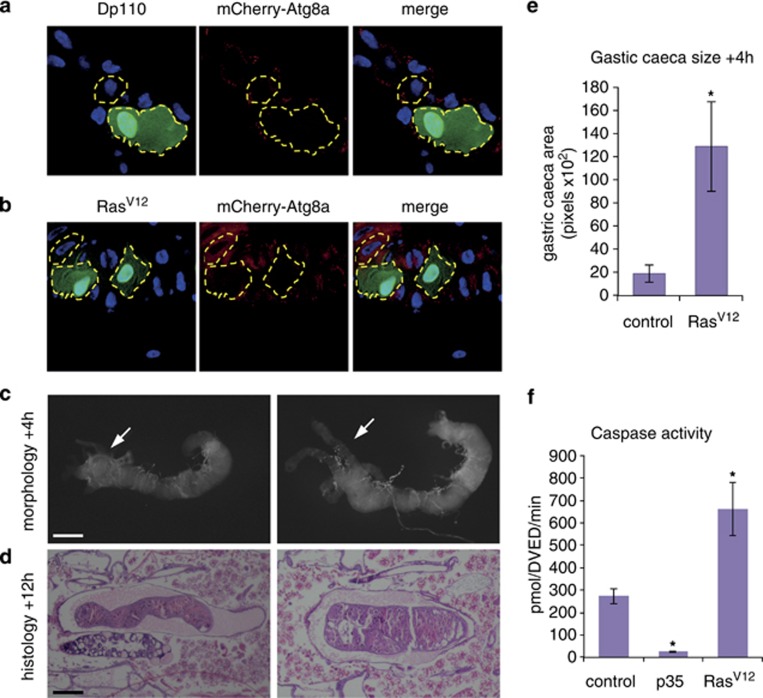

Cell growth was maintained by expression of positive regulators of class I PI3K, including the active subunit of PI3K Dp110 and activated RasV12 in mosaic clones of cells in gastric caeca of the midgut. This revealed that maintenance of growth signalling resulted in enlarged cells compared with the neighbouring control cells with reduced Atg8a puncta (Figures 3a and b). The expression of RasV12 in the entire midgut resulted in a large midgut with delayed degradation, as gastric caeca still persisted at +4 h RPF and less condensed midgut was observed at +12 h RPF compared with the control (Figures 3c and d). Quantification of the size of gastric caeca showed a significant increase when RasV12 was expressed compared with the control (Figure 3e). These data show that maintaining growth results in suppression of autophagy and supports a role for growth arrest in midgut PCD.

Figure 3.

Maintenance of growth delays midgut removal. Mosaic clones of (a) Dp110 (hsFLP; mcherry-Atg8a/UAS-Dp110; Act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-nlsGFP) and (b) RasV12 (hsFLP; mcherry-Atg8a/+ Act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-nlsGFP/UAS-RasV12) from 0 h RPF gastric caeca marked by GFP (green) have decreased levels of mCherry-Atg8a puncta (red) compared with the neighbouring cells and larger cell size. A Dp110 or RasV12 clone and neighbouring cells are outlined. Scale bar in (a) represents 50 μm in all panels in (a) and (b). (c) Morphology of midguts at +4 h RPF showing control (left, NP1-GAL4/+) compared with RasV12 (right, NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-RasV12/+) showing persistent gastric caeca (arrow) compared with the absent gastric caeca in the control (arrow). (d) Histological analysis of paraffin sections at +12 h RPF of control (left, NP1-GAL4/+) and RasV12 (right, NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-RasV12/+) shows less condensed midgut compared with control. Scale bars in (c and d) represent 200 μm. (e) Quantification of gastric caeca size (average pixels±S.D.) at +4 h RPF from control (NP1-GAL4/+) and RasV12 overexpression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS- RasV12/+ (N=8 and 7, respectively). *P<0.001 (compared with the control). (f) Caspase activity was measured from −4 h RPF larval lysates on DEVD-AMC, represented as pmol DEVD/min. The expression of p35 in the midgut inhibits the majority of caspase activity present in larvae. Data are mean from three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E.M. *P<0.05 (compared with the control)

We have previously shown that the caspase Decay is responsible for most of the caspase activity in the midgut and knockdown of decay or inhibition of caspase activity does not affect midgut degradation.3 To determine if caspase activity is affected by growth signalling, the levels of caspase-3-like activity in late third instar larvae were measured by cleavage of DEVD-AMC. Compared with the reduction in caspase activity when p35 is expressed in the midgut there was an increase in caspase activity when RasV12 was expressed (Figure 3f). This suggests that caspases remain active in the midgut in the presence of growth signals. There are several examples of non-apoptotic functions of caspases in Drosophila including border cell migration, sperm individualization, aristae shaping, dendrite pruning, sensory organ precursor differentiation and in the innate immune response.30 The high level of caspase activity in the midgut raises the possibility of non-apoptotic functions of caspases in this tissue.

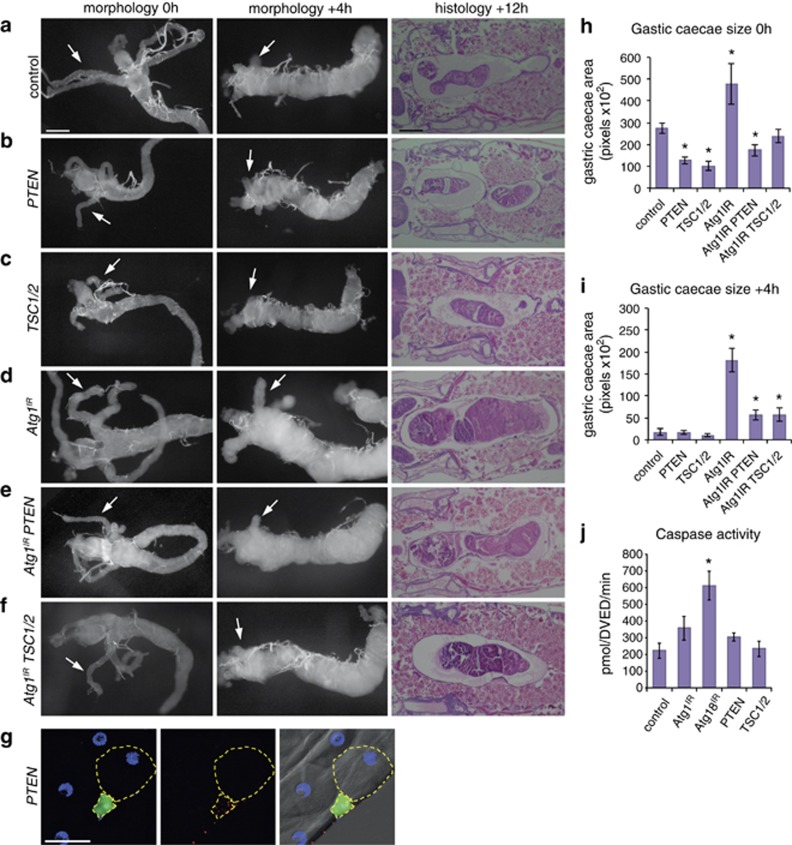

Inhibition of growth results in smaller midguts, which is suppressed by autophagy inhibition

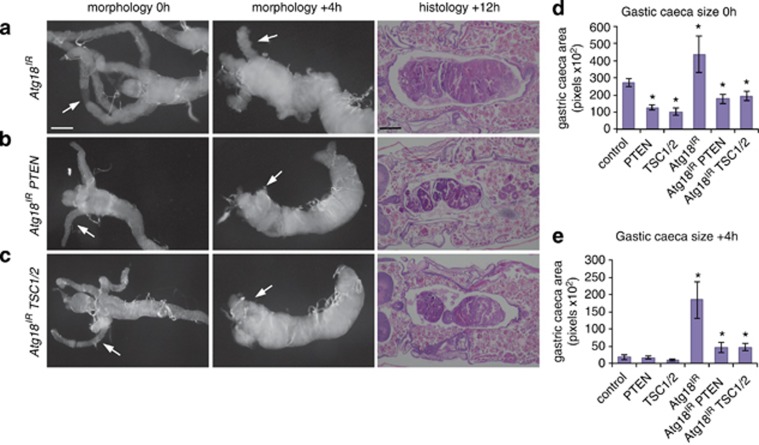

As maintenance of growth is sufficient to delay midgut removal, we examined the effect of inhibiting the class I PI3K pathway by expression of the negative regulators, PTEN and TSC1/TSC2. The expression of either PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 resulted in smaller midguts at 0 h RPF compared with controls (Figures 4a–c). Although the larval midguts were smaller, they appeared to undergo rapid degradation and were particularly fragile to dissect at +4 h RPF (Figure 4a–c). Mosaic clones expressing PTEN in the midgut of feeding larvae resulted in autophagy induction, as shown by Atg8a puncta, and a smaller cell size compared with the surrounding wild-type cells (Figure 4g). Quantification of the size of gastric caeca showed a significant decrease when PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 were expressed compared with the control at 0 h RPF (Figure 4h). Caspase activity levels were similar to controls when either PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 were expressed in the midgut of late third-instar larvae (Figure 4j).

Figure 4.

Autophagy inhibition delays midgut removal that is suppressed by inhibition of PI3K pathway. Morphology of midguts at 0 h RPF (left) and +4 h RPF (middle) showing (a) control (NP1-GAL4/+) compared with (b) PTEN expression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-PTEN/+) and (c) TSC1/2 expression (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-TSC1, UAS-TSC2/+) showing decreased size with contracted gastric caeca at 0 h RPF and smaller midgut at +4 h RPF. Histological analysis of paraffin sections at +12 h RPF (right) shows significant midgut contraction in (b) PTEN expression and (c) TSC1/2 expression compared with control (a) (NP1-GAL4/+). (d) Inhibition of autophagy severely delays midgut degradation. Morphology of midguts at 0 h RPF (left) and +4 h RPF (middle) show a significant delay in midgut histolysis in (d) Atg1IR (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg1IR/+) compared with (a) control as seen by the presence of less-contracted gastric caeca at +4 h RPF (arrows). Histological analysis of paraffin sections at +12 h RPF (right) shows an enlarged midgut in (d) Atg1IR compared with (a) control. The combined expression of (e) Atg1IR PTEN and (f) Atg1IR TSC1/2 suppressed the delay in midgut histolysis with greater contraction of gastric caeca at +4 h RPF (arrows) compared with (d) Atg1IR alone. The delayed midgut histolysis in (d) Atg1IR is reduced by co-expression of (e) PTEN or (f) TSC1/2 at +12 h RPF. Scale bars in (a) represent 200 μm in all panels. (g) Mosaic clones of PTEN (hsFLP; mCherry-Atg8a/+ Act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-nlsGFP/UAS-PTEN) marked by GFP (green) and DNA (blue) have smaller cell size with increased autophagy compared with the neighbouring cells. Scale bar in (g) is 50 μm. (h) Quantification of gastric caeca size (average pixels±S.D.) at 0 h RPF from control, PTEN, TSC1/2, Atg1IR, Atg1IR PTEN and Atg1IR TSC1/2 (N=10, 12, 9, 8, 5 and 12, respectively). *P<0.001 (compared with the control). (i) Quantification of gastric caeca size (average pixels±S.D.) at +4 h RPF measured from control, PTEN, TSC1/2, Atg1IR, Atg1IR PTEN and Atg1IR TSC1/2 (N=8, 8, 9, 9, 10 and 9, respectively). *P<0.001 (compared with the control). (j) Caspase activity was measured from −4 h RPF larval lysates on DEVD-AMC, represented as pmol DEVD/min. Data are mean from three independent experiments, with error bars representing S.E.M. *P<0.05 (compared with control)

To determine if downregulation of growth signalling was required for the induction of autophagy during midgut removal, we examined the interaction between the knockdown of autophagy genes Atg1 and Atg18 combined with expression of either PTEN or TSC1/TSC2. The inhibition of autophagy by knockdown of Atg1 or Atg18 severely delayed midgut removal, consistent with previous studies (Figures 4d and 5a).3 When Atg1 knockdown was combined with either PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 expression the midgut size was more similar to the control at 0 h RPF compared with PTEN and TSC1/TSC2 expression or Atg1 knockdown alone (Figures 4e). Similarly, when Atg18 knockdown was combined with either PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 expression the growth retardation seen at 0 h RPF of PTEN and TSC1/TSC2 expression alone was suppressed (Figures 5b). Furthermore, the combined Atg1 knockdown and PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 resulted in an increase in contraction of gastric caeca at +4 h RPF and more condensed midgut at +12 h RPF compared with Atg1 knockdown alone (Figures 4e). Again, similar results were observed with Atg18 knockdown combined with PTEN or TSC1/TSC2 expression showing an increase in contraction of gastric caeca at +4 h RPF and more condensed midgut at +12 h RPF compared with Atg18 knockdown alone (Figures 5b). This suggests that although the degradation of growth-arrested midguts requires autophagy, there is a feedback between autophagy and downregulation of growth signalling. An alternative model is that autophagy and growth signalling act in parallel pathways during midgut removal. This also raises the possibility that autophagy may have different influences on cell survival before and after growth arrest.

Figure 5.

Autophagy inhibition by Atg18 knockdown delays midgut removal that is suppressed by inhibition of PI3K pathway. Morphology of midguts at 0 h RPF (left) and +4 h RPF (middle) show a significant delay in midgut histolysis in (a) Atg18IR (NP1-GAL4/+ UAS-Atg18IR/+) as seen by the presence of less-contracted gastric caeca at +4 h RPF (arrows). Histological analysis of paraffin sections at +12 h RPF (right) shows an enlarged midgut in (a) Atg18IR. The combined expression of (b) Atg18IR PTEN and (c) Atg18IR TSC1/2 suppressed the delay in midgut histolysis with greater contraction of gastric caeca at +4 h RPF (arrows) compared with (a) Atg18IR alone. The delayed midgut histolysis in (a) Atg18IR is reduced by co-expression of (b) PTEN or (c) TSC1/2 at +12 h RPF. Scale bars represent 200 μm. (d) Quantification of gastric caeca size (average pixels±S.D.) at 0 h RPF from control, PTEN, TSC1/2, Atg18IR, Atg18IR PTEN and Atg18IR TSC1/2 (N=10, 12, 9, 7, 6 and 10, respectively). *P<0.001 (compared with the control). (e) Quantification of gastric caeca size (average pixels±S.D.) at +4 h RPF from control, PTEN, TSC1/2, Atg18IR, Atg18IR PTEN and Atg18IR TSC1/2 (N=8, 8, 9, 9, 5 and 6, respectively). *P<0.001 (compared with the control)

Salvador–Warts–Hippo pathway is not involved in regulating midgut cell death

The highly conserved Salvador–Warts–Hippo pathway is a negative regulator of cell and tissue growth, and central to the pathway are the Hippo (Hpo) and Warts (Wts) kinases that act to inhibit the Yorkie transcription factor.31 The Salvador–Warts–Hippo pathway has been shown to be required for correct removal of salivary glands.27 The salivary glands of wts mutants do not undergo growth arrest, have decreased autophagy and persist beyond the normal time of degradation. Furthermore, the wts mutant salivary glands have altered PI3K signalling and the delayed degradation could be rescued by TOR inhibition. Given this, together with the role of PI3K pathway and autophagy in midgut cell death, we examined the role of wts in the degradation of the midgut to determine if this is a common requirement for PCD.

The knockdown of wts in the midgut did not alter the morphology or timing of midgut degradation (Supplementary Figures 2a, b and e). The gastric caeca were contracted at +4 h RPF similar to the control and the midgut condensed at +12 h RPF (Supplementary Figures 2a, b and e). In addition, the midgut appeared to undergo normal degradation in wtslacZ mutants (Supplementary Figures 2c and e). Mosaic clonal analysis also showed that expression of yorkie does not alter cell growth (Supplementary Figure 2d). Thus, unlike in the salivary gland where wts is required for growth arrest and PCD, Wts-dependent growth arrest pathway is dispensable for midgut degradation. This highlights the tissue-specific requirements for different signalling pathways and the importance of understanding how these act to regulate autophagy not only in cell survival but also in cell death.

Discussion

Our work provides critical evidence that the autophagic cell death in Drosophila larval midgut is dependent upon growth inhibition. The developmental PCD of salivary glands that requires autophagy is dependent on downregulation of PI3K.18 The developmental induction of autophagy in the fat body that occurs in response to ecdysone also appears to be mediated by downregulation of PI3K signalling.32 We now demonstrate that this downregulation of PI3K signalling is required for autophagic removal of obsolete larval midgut tissue.

We also found that despite apparent similarity in the requirement of autophagy for the destruction of the larval midgut and salivary glands, there are distinct differences between these tissues. While the removal of the salivary glands and midgut are dependent on autophagy, midgut degradation does not require the Salvador–Warts–Hippo growth inhibitory pathway. This study further reveals a relationship between autophagy and cell growth, as inhibition of autophagy maintained growth signalling and suggests that although they may be coordinately regulated there appears to be feedback signalling with autophagy required for downregulation of class I PI3K signalling. This is a surprising finding and we propose the following possibilities for the mechanism/s of this novel feedback regulation: (i) autophagy has a role in the downregulation of growth signalling, potentially at the level of the cell surface receptor or PIP3 degradation/recruitment to autophagosome, (ii) autophagy indirectly degrades a negative regulator/inhibitor of the PI3K signalling, and (iii) autophagy is involved in a parallel pathway.33, 34

In most circumstances starvation-induced autophagy has a role in cell survival rather than cell death. Although the induction of autophagy during cell death appears to require the downregulation of growth signalling, these same pathways can result in the induction of autophagy as a survival response in other situations. However, autophagic cell death may overcome feedback with growth signals resulting in maintained levels of autophagy that ultimately result in cell destruction. This may correlate with the levels of Atg1 gene expression induced during metamorphosis, which is not seen under starvation conditions. In response to starvation, Atg8 in yeast and Atg8a in Drosophila fat body are transcriptionally upregulated, whereas other Atg genes are not.35, 36, 37 This is in contrast to the increase in expression of Atg1 and many of the Atg genes during salivary gland and midgut cell death, where only a slight increase in Atg8a is observed.3, 21, 22, 38 Although autophagy induction in both survival and death may occur in response to similar growth signals, distinct components of the autophagy pathway may be rate-limiting.

Studies in Drosophila suggest that most of the autophagic cell death occurs when nutrients are limiting such as the non-feeding stage of metamorphosis, depletion of extra-embryonic tissue, and in oogenesis during nutrient limitation.2, 6 Thus in such context autophagy may be induced in response to reduced growth signals under nutrient-limiting conditions to remove obsolete cells/tissues. These observations may provide a conceptual basis for the dual role of autophagy in cell growth and cell death in tumour cells.9 Several important questions arise from this study. For example, how does autophagy influence cell growth and mediate cell death? Does autophagy result in the specific degradation of either survival or death-inhibiting factors, or by general degradation of the cell mass?39 Future work will address these critical issues.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

RNAi line UAS-Atg18IR was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (Vienna, Austria). The following stocks were from the Bloomington stock center (Bloomington, IN, USA): UAS-Atg1IR(y1 sc* v1; P(TRiP.GL00047)attP2/TM3, Sb1), UAS-Rasv12, UAS-Dp110, hsflp UAS-nlsGFP, Act>CD2>GAL4. The midgut driver, NP1-GAL4, was obtained from the Drosophila genetic resource center (Kyoto, Japan). Other stocks were obtained from: UAS-Atg16B from T Neufeld; UAS-PTEN, UAS-TSC1,UAS-TSC2, UAS-wtsIR, UAS-hpoIR and wartslacZ from K Harvey. All flies were maintained and crosses performed at 25 °C. Larvae were grown on food containing 0.05% bromophenol blue as described,40 and staged by collection of wandering larvae onto damp Whatmann paper in a petri dish.

Promoter-mCherry-Atg8a reporter for autophagy detection

Autophagy was assessed by mCherry-Atg8a puncta formation. A region 2 kb upstream of Atg8a (CG32672) was inserted upstream of mCherry-Atg8a in the pCaSpeR4 Drosophila transformation vector, as was previously described for a similar GFP-Atg8a reporter line.3 The resulting plasmid pCaSpeR4-promoter-mCherry-Atg8a was used to generate transgenic Drosophila lines using standard procedures. Owing to a lack of suitable reagents for monitoring autophagy flux, Atg8a puncta is commonly used for detecting autophagy in vivo in Drosophila.

Histology

For hematoxylin and eosin staining of whole pupal sections, +12 h RPF pupae were fixed in FAAG (85% ethanol, 4% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid and 1% glutaraldehyde), then paraffin embedded before sectioning and staining as previously described.18, 23 The controls were w1118 Drosophila crossed to either NP1-GAL4, or the experimental UAS-transgene line being analysed. For each genotype a minimum of 10 pupae were examined using a stereozoom microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

Midguts of the required genotype were dissected from appropriately staged animals in PBS then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-phospho-Drosophila-Akt (1 : 200) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and mouse anti-Fasciclin III (1 : 100) (7G10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa, IA, USA). Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit Alexa-FLUOR 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, CA, USA), anti-mouse Alexa-FLUOR 566 (Molecular Probes). Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to detect DNA. The samples were imaged with a Biorad confocal microscope (Bio-Rad Microscience, Hempstead, UK; at Detmold Imaging Core Facility, Hanson Institute, Adelaide, SA, Australia).

Live GFP and mCherry imaging

To assay for tGPH, the reporter was in an NP1-GAL4 background and crossed with appropriate control or experimental flies. Midguts from pupae staged +2 h RPF were dissected in PBS, stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) and imaged immediately without fixation using a Biorad confocal microscope. To assay for mCherry-Atg8a, midguts were dissected in PBS, briefly fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with either Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) or DAPI (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to detect DNA.

Light microscopy

Pupae were staged 0 or +4 h RPF and midguts were dissected in PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS and examined using a stereozoom microscope (Olympus). Measurements of gastric caeca size were done using either Zeiss automeasure software as in Figure 1, or Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) magnetic lasso tool. The histogram function was used to determine pixel area.

Imaging

Confocal images were obtained using a BioRad Radiance 2100 confocal microscope with Argon ion 488 nm (14 mw) and Green HeNe 543 nm (1.5 mw) lasers and an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope with a 40 × UPLAPO (NA=1.2 water) objective. The dual labelled samples were imaged with two separate channels (PMT tubes) in a sequential setting. Green fluorescence was excited with an Ar 488 nm laser line and the emission viewed through a HQ515/30 nm narrow band barrier filter in PMT1. Red fluorescence was excited with a HeNe 543 nm laser line and the emission viewed through a long-pass barrier filter (E570LP) in PMT2. Automatically all signals from PMTs 1 and 2 were merged. Image were captured using Confocal Assistant software for Microsoft Windows (Todd Clark Brelje, Bethesda, MD, USA) and compiled using Photoshop CS5 (Adobe).

Caspase assays

The caspase activity assays were performed as previously described40 using 30 μg of late larval protein lysate with 100 μM of DEVD-AMC (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) made up to a final volume of 100 μl in caspase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose, 5 mM DTT, 0.5% TritonX-100, 4% glycerol with protease inhibitor mix (Roche)). The fluorescence was measured over a 3 h time course at 30 min intervals using a FluoStar spectrophotometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) (excitation, 385 nm; emission, 460 nm) and the activity calculated as previously described.40

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Quantitation of the level of RNAi knockdown of various lines was done by qPCR (Supplementary Figure 3). Total RNA was isolated from Drosophila midguts using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA) and oligo dT primer, with 1 μg of total RNA. Real-Time PCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Mortlake, NSW, Australia) using RT2 Real-Time SYBR Green/ROX PCR MasterMix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Reactions were performed in triplicate and the mRNA expression levels normalized against the internal control gene rp49 using the ΔΔCT method. Primer sets used are: rp49 F 5′-CCAGTCGGATCGATATGCTAA-3′ R 5′-ACGTTGTGCACCAGGAACTT-3′ Atg1 F 5′-ACGGCGGACAAGATTCTCTA-3′ R 5′ GCTGCTGCAATATGCTCAAA-3′ Atg18 F 5′-AGGTGACCGACGTGTTTAGC-3′ R 5′-ACGGTGGGAATGGAATACAC-3′ wts F 5′-GAGGTGCTGGAGAGAAGTGG-3′ R 5′-CAGGGTTTTCTCCCAGTTGA-3′.

Statistical analysis of data

Student's t-test was used for all statistical analysis unless otherwise stated. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. or mean±S.E.M., as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grant (626923) and a Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1002863) to SK, and NIH grant GM079431 to EHB. We thank Dr Kieran Harvey, the Australian Drosophila Research Support Facility, Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, and Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for Drosophila stocks, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa) for antibodies, Earanee Niedzwiecki and Tina Fortier for maintaining stocks and Amanda Rogers for tissue processing.

Glossary

- PCD

programmed cell death

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- RPF

relative puparium formation

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by M Piacentini

Supplementary Material

References

- Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ 2012. 19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D, Nicolson S, Kumar S. Cell death by autophagy: facts and apparent artefacts. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:87–95. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D, Shravage B, Simin R, Mills K, Berry DL, Baehrecke EH, et al. Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1741–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D, Shravage B, Simin R, Baehrecke EH, Kumar S. Larval midgut destruction in Drosophila: not dependent on caspases but suppressed by the loss of autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:163–165. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Cooksey BA, Baehrecke EH. Steroid regulation of midgut cell death during Drosophila development. Dev Biol. 2002;250:101–111. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi F, Levine B. The role of autophagy in mammalian development: cell makeover rather than cell death. Dev Cell. 2008;15:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:460–470. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy M, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Martin SJ. Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell. 2011;42:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP. TOR-dependent control of autophagy: biting the hand that feeds. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arico S, Petiot A, Bauvy C, Dubbelhuis PF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, et al. The tumor suppressor PTEN positively regulates macroautophagy by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35243–35246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Schuldiner O, Neufeld TP. Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev Cell. 2004;7:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YY, Neufeld TP. An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2004–2014. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YC, Chittaranjan S, Barbosa SG, McCall K, Gorski SM. Effector caspase Dcp-1 and IAP protein Bruce regulate starvation-induced autophagy during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1127–1139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezis IP, Lamark T, Velentzas AD, Rusten TE, Bjorkoy G, Johansen T, et al. Cell death during Drosophila melanogaster early oogenesis is mediated through autophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:298–302. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni N, McMillan SC, Chaudhary R, Mok J, Reed BH. Autophagy promotes caspase-dependent cell death during Drosophila development. Autophagy. 2009;5:329–338. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Baehrecke EH, Thummel CS. Steroid regulated programmed cell death during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development. 1997;124:4673–4683. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Wendel DP, Reid P, Lam G, Thummel CS, Baehrecke EH. E93 directs steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2000;6:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Clough EA, Yellon P, Teslovich TM, Stephan DA, Baehrecke EH. Genome-wide analyses of steroid- and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2003;13:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski SM, Chittaranjan S, Pleasance ED, Freeman JD, Anderson CL, Varhol RJ, et al. A SAGE approach to discovery of genes involved in autophagic cell death. Curr Biol. 2003;13:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daish TJ, Mills K, Kumar S. Drosophila caspase DRONC is required for specific developmental cell death pathways and stress-induced apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K, Daish T, Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK, Kumar S. The Drosophila melanogaster Apaf-1 homologue ARK is required for most, but not all, programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:809–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DN, Baehrecke EH. Caspases function in autophagic programmed cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:275–284. doi: 10.1242/dev.00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Baehrecke EH. Steroid regulation of autophagic programmed cell death during development. Development. 2001;128:1443–1455. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Baehrecke EH. Warts is required for PI3K-regulated growth arrest, autophagy, and autophagic cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1466–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila's insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev Cell. 2002;2:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma SC, Thomas G. Regulation of cell size in growth, development and human disease: PI3K, PKB and S6K. Bioessays. 2002;24:65–71. doi: 10.1002/bies.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuranaga E. Beyond apoptosis: caspase regulatory mechanisms and functions in vivo. Genes Cells. 2012;17:83–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K, Tapon N. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:182–191. doi: 10.1038/nrc2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusten TE, Lindmo K, Juhasz G, Sass M, Seglen PO, Brech A, et al. Programmed autophagy in the Drosophila fat body is induced by ecdysone through regulation of the PI3K pathway. Dev Cell. 2004;7:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandilands E, Serrels B, McEwan DG, Morton JP, Macagno JP, McLeod K, et al. Autophagic targeting of Src promotes cancer cell survival following reduced FAK signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:51–60. doi: 10.1038/ncb2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Baba M, Ishihara N, Miyazawa K, Ohsumi M, Yoshimori T, et al. Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:435–446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinke I, Schutz CS, Katzenberger JD, Bauer M, Pankratz MJ. Nutrient control of gene expression in Drosophila: microarray analysis of starvation and sugar-dependent response. EMBO J. 2002;21:6162–6173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Puskas LG, Komonyi O, Erdi B, Maroy P, Neufeld TP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies FKBP39 as an inhibitor of autophagy in larval Drosophila fat body. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1181–1190. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Simon CR, Woodard CT, Baehrecke EH. Genetic mechanism for the stage- and tissue-specific regulation of steroid triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2002;252:138–148. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezis IP, Shravage BV, Sagona AP, Johansen T, Baehrecke EH, Stenmark H. Autophagy as a trigger for cell death: autophagic degradation of inhibitor of apoptosis dBruce controls DNA fragmentation during late oogenesis in Drosophila. Autophagy. 2010;6:1214–1215. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D, Mills K, Kumar S. Methods and protocols for studying cell death in Drosophila. Methods Enzymol. 2008;446:17–37. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.