Abstract

Nearly a century ago, cell biologists postulated that the chromosomal aberrations blighting cancer cells might be caused by a mysterious organelle—the centrosome—that had only just been discovered. For years, however, this enigmatic structure was neglected in oncologic investigations and has only recently reemerged as a key suspect in tumorigenesis. A majority of cancer cells, unlike healthy cells, possess an amplified centrosome complement, which they manage to coalesce neatly at two spindle poles during mitosis. This clustering mechanism permits the cell to form a pseudo-bipolar mitotic spindle for segregation of sister chromatids. On rare occasions this mechanism fails, resulting in declustered centrosomes and the assembly of a multipolar spindle. Spindle multipolarity consigns the cell to an almost certain fate of mitotic arrest or death. The catastrophic nature of multipolarity has attracted efforts to develop drugs that can induce declustering in cancer cells. Such chemotherapeutics would theoretically spare healthy cells, whose normal centrosome complement should preclude multipolar spindle formation. In search of the ‘Holy Grail' of nontoxic, cancer cell-selective, and superiorly efficacious chemotherapy, research is underway to elucidate the underpinnings of centrosome clustering mechanisms. Here, we detail the progress made towards that end, highlighting seminal work and suggesting directions for future research, aimed at demystifying this riddling cellular tactic and exploiting it for chemotherapeutic purposes. We also propose a model to highlight the integral role of microtubule dynamicity and the delicate balance of forces on which cancer cells rely for effective centrosome clustering. Finally, we provide insights regarding how perturbation of this balance may pave an inroad for inducing lethal centrosome dispersal and death selectively in cancer cells.

Keywords: centrosome declustering, chemotherapy, spindle assembly checkpoint, microtubule dynamics

Facts

Cancer cells cluster supernumerary centrosomes to avert potentially lethal multipolar mitoses.

Whereas cancer cells exhibiting centrosome amplification rely on clustering for survival, this process is dispensable to healthy human cells with a numerically normal centrosome complement.

As clustering is cancer cell-specific, targeted inhibition of centrosome clustering mechanisms offers an opportunity for nontoxic chemotherapy.

Open Questions

What benefits do centrosome amplification and clustering confer on cancer cells?

Is microtubule dynamicity crucial for centrosome clustering?

Is declustering simply the failure of centrosome clustering mechanisms or are there cellular factors that antagonize clustering mechanisms?

What are the specific modes of action of the known centrosome declustering drugs?

The multitude which is not brought to act as a unity, is confusion.

-Blaise Pascal

At the turn of the 20th century, pioneer cell biologists observed an enigmatic structure residing near the cell center. This curious organelle was denominated ‘centrosome' by renowned scientist Theodor Boveri, who noticed, along with his contemporary David Paul von Hansemann, that malignant cells often contain multiple copies of the centrosome along with an abnormal chromosome complement.1 At that time, they conjectured that cells possessing a surfeit of centrosomes may be predisposed to asymmetric karyokinesis and the resultant aneuploid state may drive malignancy. Although this visionary notion was largely ignored for almost a century, the centrosome today has reclaimed, much like its interphase location, a central position in oncologic investigation.

The centrosome, which is the primary microtubule organizing center of the cell, duplicates during interphase to produce a second partner with which it constructs a bipolar, fusiform, spindle apparatus during mitosis. Dynamic microtubules emanating from two centrosomes (spindle poles) then apprehend the kinetochores of duplicated sister chromatids. Once a critical level of tension or stretch is established across each sister-chromatid pair, anaphase ensues, causing irreversible sister-chromatid segregation to the opposite poles of the cell.2 Having only two centrosomes is thus crucial to ensure equal partitioning of genetic material between the two daughter cells. Cancers, especially the more aggressive ones, harbor too many centrosomes. This feature correlates strongly with chromosomal instability (CIN), karyotypic heterogeneity, and other malignant phenotypes.3, 4 Supernumerary centrosomes can prove lethal by inducing spindle multipolarity with subsequent anaphase catastrophe5 or multipolar mitosis.6, 7, 8

Much evidence now supports a causative link between CIN and malignant transformation, particularly in multi-step carcinogenesis.9, 10, 11 However, dust has not settled on the debate of whether a low level of aneuploidy is merely an outcome of tolerable mitotic errors accrued by cancer cells or whether it is an evolutionarily favored feature selected for conferring some advantage on them. In this review, we discuss the newly emerging paradigm that invokes a tumor-promoting role for low-level, whole-chromosome aneuploidy and elaborate on a strategy that cancer cells utilize to both manage extra centrosomes and maintain optimal aneuploidy, viz, centrosome clustering. We also review how centrosome amplification often occurs in cancer cells. Finally, we discuss how centrosome clustering mechanisms represent attractive targets for cancer cell-selective chemotherapy and a promising new direction in our effort to counter the clever schemes cancer cells have evolved to ensure their survival.

The Centrosome: a Miniscule Marvel and Headquarters of Cellular Control

The centrosome is a membrane-less organelle composed of a cloud of pericentriolar material (PCM), and in most metazoan cells a pair of mother and daughter centrioles that differ in age and maturity.12 The orthogonally oriented centrioles are linked together by a loose, proteinaceous tether.13 PCM components include γ-tubulin ring complexes (γ-TuRCs) and the microtubules they nucleate, microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), Homologous to AUgmin Subunits (HAUS) complexes, and several other integral and satellite proteins.14 The composition and architecture of the centrioles have been characterized in great detail.14, 15, 16 Centrioles are proximo-distally polarized, radially symmetric, cylindrical structures typically composed of nine microtubule triplets, lumenal proteins such as centrin-2 and 3, and distal components such as centriolin.14, 15, 16 Recent research has revealed that the mother centriole is perhaps not a bonafide template for daughter centriole formation; rather, the mother is a platform for the expeditious recruitment of duplication factors to the PCM and/or their activation within it.17 Furthermore, the mother centriole organizes and stabilizes the PCM and regulates its size.18, 19 The centrosome organizes the microtubule cytoskeleton of a eukaryotic cell by nucleating, anchoring, and releasing microtubules as needed.20 During mitosis, the centrosome anchors a radial array of astral, kinetochore, and interpolar microtubules, which form the elegant spindle apparatus with the help of various MAPs and motor proteins.21 As spindle abnormalities may result in diverse cellular calamities, cells regulate centrosome structure and function very precisely.

Excess Baggage: how Cancer Cells Acquire Extra Centrosomes

An increase in the number of centrosomes, termed centrosome amplification, can arise from various aberrant processes, including cell–cell fusion, centrosome fragmentation, de novo centriole formation, dysregulation of the canonical centrosome duplication cycle, and possibly cytokinesis failure.22, 23, 24 Regarding the last-named mechanism, it is noteworthy that a recent study demonstrated that whereas cleavage failure is unlikely to be a primary source of sustained centrosome amplification in healthy cells, this mechanism may operate in some cancer cell populations.25 In addition to exhibiting numerical abnormalities, amplified centrosomes are oftentimes abnormal in structure, function, or localization within the cell.26, 27, 28 Among the various possible etiologies of centrosome amplification, much attention has been focused on deregulation of the centrosome cycle as many cancer-associated proteins are involved in regulating centrosome duplication.29 Elucidation of the origins of centrosome overduplication may prove invaluable in designing cancer therapies.

Two to tango: how licensing factors mechanistically couple the centrosome and nuclear cycles

Normally, the centrosome duplicates precisely once during interphase coincident with DNA replication.13 Deregulation of centriole duplication factors in interphase can result in rampant centriole overduplication, as described in an excellent review recently.30 Another important cause of centrosome amplification involves derailing of the ‘licensing' mechanism that entrains the centrosome cycle with the nuclear cycle. In healthy cells, this system ensures that centriole duplication is only initiated when appropriate, that is, when only one pair of centrioles is present, and the cell is ready to divide. The licensing mechanism utilizes a small fleet of licensing factors, the presence or absence of which is an absolute block to duplication irrespective of ambient centriole-duplication-factor levels. As soon as duplication is initiated in S phase, licensure is rescinded by inactivation or removal of the licensing factors. The tight intercentriolar linker normally functions as a centrosome-intrinsic block in duplication.22, 31 This linker is relinquished (i.e., centrioles are disengaged and licensed to duplicate) for just a brief interlude, from late M/early G1 phase to the onset of centriole duplication in S phase. Several proteins are implicated in centriole disengagement, but the best-characterized licensing players are separase, Plk1, origin recognition complex1 (ORC1), and MCM5. As described below, these proteins' activities are normally coupled to critical events in the nuclear cycle to prohibit centrosome amplification and its associated liabilities.

Separase: the divisive divider

The cysteine protease, separase, normally triggers anaphase onset by cleaving the cohesin complex that holds bioriented sister chromatids together.32 It turns out that separase also mediates timely centriole licensing.31, 33, 34, 35 The cell utilizes separase's protease activity to cleave the tight intercentriolar linker to license duplication, thereby coupling centriole duplication mechanistically to the onset of sister-chromatid separation.34, 36 These data engendered the hypothesis that cohesin forms the tight intercentriolar linker. In support of this idea, all elements of the cohesin complex are found in the centrosome, and cohesin depletion results in centriole disengagement.37, 38, 39, 40 Furthermore, knockdown of an isoform of the cohesin-binding protein, SGO1 (shugoshin), causes centriole splitting.41 Intriguingly, experimental evidence also suggests that cleaved cohesin promotes continued centriole engagement,34, 38, 42 perhaps by delivering ‘engagement factors' to the centrosome to preserve centriole cohesion until G1.38 Clearly, more data are awaited to clarify how centrioles remain engaged for the appropriate segment of the cell cycle and subsequently part ways in an exquisitely timed manner.

Plk1: the preeminent primer

The activity of Plk1, a major mitotic regulator, is normally suppressed in interphase by the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) protein, BubR1.43 Nevertheless, Plk1 activity slowly rises from S through G2 and peaks in mitosis. Plk1 not only mediates centriole maturation42, 44, 45 but also primes centrioles for disengagement34 by phosphorylating cohesin and accelerating its cleavage by separase.46 In addition, Plk1 may regulate centrosomal localization of shugoshin and mediate centriole disengagement by modifying shugoshin's activity in preserving centriole cohesion.41 Although the finer details regarding this mechanism remain murky, the importance of Plk1 and cohesin in the process is evident. Plk1 also modifies the newly formed procentrioles in M phase so that they are competent to duplicate once disengaged.47 Importantly, the restriction of Plk1-mediated daughter centriole modification to M phase ensures that interphase procentrioles do not generate their own procentrioles (i.e., centriole ‘granddaughters'). Cell cycle coupling of Plk1's activities guarantees that the licensing of centriole duplication occurs apropos.

ORC1 and MCM5: the moonlighting multipliers

The DNA licensing factors, MCM5 and ORC1, may also participate in centrosome licensing. In G1, ORC1 (an ORC component) loads MCM complexes onto DNA replication origins, forming pre-replication complexes, which fulfills the DNA-licensing step.48 Concomitantly, rising Cyclin E levels promote centriole disengagement and initiation of centriole duplication. Cyclin E binds and recruits MCM5 (an MCM complex component) to the centrosome.49 Subsequently, rising Cyclin A levels induce firing of DNA replication origins, degradation of the majority of ORC1, and translocation of the remainder of ORC1 and MCM5 to the cytosol and centrosome.50, 51, 52 ORC1 removal from the nucleus prevents untimely DNA replication relicensure. At the centrosome, ORC1 and MCM5 impede centriole licensing by inhibiting Cyclin E-mediated centriole disengagement. Thus, Cyclin A elegantly coordinates the blockade of DNA replication with cessation of centriole duplication after S phase.

In summary, rigorous entrainment of the centrosome and nuclear cycles guarantees that centrioles and DNA acquire duplication licensure simultaneously. If centrioles gain license prematurely, then they duplicate out of synchrony with DNA and centrosome amplification results. The following section details how the links between centrosome and nuclear cycles frequently come undone in cancer cells.

Severing the ties that bind: how centrosome and nuclear cycle uncoupling causes centrosome amplification

Ample evidence shows that centrosome licensing factors are deregulated in cancer. For instance, separase overexpression occurs in several cancers and correlates positively with tumor grade and negatively with survival.53 Plk1 upregulation is so widespread in malignancies that it has been termed a ‘general feature of human cancer.'54 Although ORC1 and MCM5 display aberrant expression in certain transformed cells,55 MCM5 is consistently upregulated in cancers and is considered a biomarker.56, 57

Much evidence also links deregulation of centrosome licensing factors with centriole overduplication. Ectopic expression of E6 and E7 HPV oncogenes in human keratinocytes induces simultaneous upregulation of Plk1 and centrosome amplification.58 In addition, Plk1 expression is upregulated in patients suffering from premature chromatid separation syndrome, a disorder characterized by its namesake as well as centrosome amplification and increased incidence of childhood cancers.43 Consistent with the idea that MCM5 is a negative licensor of centriole disengagement, MCM5 knockdown in Chinese hamster ovary cells triggers S-phase arrest and centriole overduplication.49 Similarly, ORC1 depletion in U2OS cells results in coincidental Cyclin-E upregulation and premature centriole disengagement, supporting the idea that ORC1 also functions as a negative regulator of centriole licensing.49, 51 The key point illuminated under the clarifying headlamps of these studies is that the deregulation of centriole duplication and licensing factors often precipitates centrosome amplification. As centrosomes are amplified in solid and hematological malignancies of virtually every organ system,59, 60 a closer look at the cellular consequences of centrosome amplification is warranted.

Rome cannot have too many Caesars: the problem with centrosome amplification

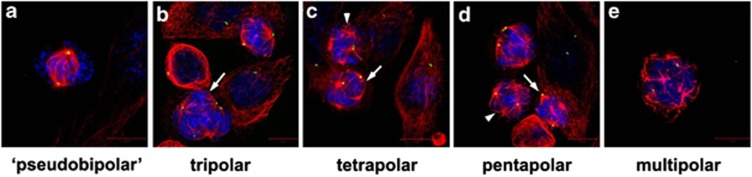

The presence of more than two centrosomes within a cell can potentially lead to spindle multipolarity during mitosis, which increases the number of spindle poles to which sister chromatids can become attached. The result is the formation of more than two daughter cells that may be inviable owing to catastrophic levels of chromosomal loss (viz, death-inducing, high-grade aneuploidy). Paradoxically, however, cancer cells frequently harbor extra centrosomes and yet manage to thrive. It is being revealed, in piecemeal fashion, that cancer cells hijack cellular mechanisms and deploy a sophisticated and extensive arsenal of tactics to cluster supernumerary centrosomes into two polar groups.6, 61, 62 Centrosome clustering allows the formation of a ‘pseudo-bipolar' mitotic spindle as depicted in Figure 1a, which averts multipolarity, the varying degrees of which are depicted in Figures 1b–e. A closer look at this clustering phenomenon has uncovered the formation of a transient multipolar spindle intermediate before the centrosome clustering mechanism engages.63, 64 During this brief multipolar state, there is accumulation of merotelic kinetochore–microtubule attachments (i.e., attachment of microtubules from two different spindle poles to the same kinetochore), which are poorly sensed by the SAC mechanism. Merotelic attachments can severely compromise genomic integrity and promote CIN by causing both structural and numerical karyotypic abnormalities.65 The consequent low-grade aneuploidy is not merely an undesirable-but-benign consequence of cellular transformation but rather a characteristic that actually drives malignancy and tumor evolution.66 This finding is corroborated by voluminous evidence that centrosome amplification is an early event in carcinogenesis, as it occurs in precancerous and preinvasive lesions.26, 67 As a result, an in-depth understanding of how centrosome amplification and clustering occur might prove to form the cornerstone of therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1.

Pseudo-bipolar spindle formation prevents mitotic catastrophe-inducing multipolarity. (a) Confocal immunofluorescence image depicts a human prostate cancer PC3 cell with centrosomes clustered at two opposite poles. The remaining cells are of the same type but have failed to cluster centrosomes, resulting in varying degrees of multipolarity (b–e). Arrows indicate cells exhibiting the particular degree of multipolarity mentioned beneath the image. Arrowheads indicate representative acentrosomal poles. (Centrin=green; microtubules=red; DNA=blue)

Surviving with Surplus: Managing Supernumerary Centrosomes by Centrosome Clustering

A fascinating line of inquiry reflects on how cancer cells even manage to survive with extra centrosomes. In certain cells with supernumerary centrosomes, mechanisms such as selective PCM removal lead to inactivation of at least some of the centrosomes so that they cannot function as spindle poles.68 However, nothing is currently known about whether cancer cells employ such a strategy to consign extra centrosomes to inconsequence. Another question to ponder is whether cancer cells degrade extra centrosomes to evade multipolarity, a phenomenon observed in oogenesis of certain species in which centrosomes are paternally inherited during development.69 A more extensively characterized stratagem used by cancer cells to ensure bipolar mitoses is the clustering of extra centrosomes. The following section details the centrosome clustering mechanisms that cancer cells use to mute the catastrophic impact of centrosome amplification and avoid high-grade aneuploidy.

Check-in time for passengers: how spindle assembly checkpoint activation and the chromosome passenger complex aid and abet in centrosome clustering

Cancer cells with supernumerary centrosomes cleverly deploy the mitotic cell's primary spindle self-diagnostic system, the SAC, for their benefit. The SAC normally prevents anaphase entry until all chromosomes have bioriented on the mitotic spindle.2, 70, 71 The SAC-mediated delay in anaphase onset also provides time for effecting centrosome clustering, thereby promoting pseudo-bipolar mitosis and daughter cell survival. The following observations support the idea that the SAC facilitates centrosome clustering. SAC-mediated, delayed passage through mitosis allows Plk4-overexpressing fruitfly larvae, which exhibit centrosome amplification, to cluster their extra centrosomes.68 Moreover, in near tetraploid Drosophila S2 cells, which naturally exhibit centrosome amplification, clustering is inhibited by disabling SAC function through Mad2 knockdown.6 However, when Mad2 knockdowns are treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, which delays anaphase onset, clustering is accomplished. These data bolster the notion that the SAC is required for clustering because it delays anaphase onset, which provides extra time for centrosome clustering.

Many cancer cell lines exhibit SAC protein overexpression, which presumably equips them with a more robust SAC for effective centrosome clustering. For example, Mad2 is overexpressed and associated with poorer prognosis and/or advanced tumor grade in certain lines of lymphoma,10 osteosarcoma,72 soft tissue sarcoma,73 testicular germ cell tumor,74 neuroblastoma,75 retinoblastoma,75 and cancers of the bladder,75 colon,76 esophagus,77 liver,78 lung,79 and stomach.80 SAC involvement in tumorigenesis, however, is very complex and context-dependent. For instance, downregulation of SAC proteins such as Mad2 is also observed in certain liver,81 ovarian,82 nasopharyngeal,83 and breast84 cancer lines. Complete knockdown of Mad2 is embryonically lethal and results in severe aneuploidy and apoptosis in mice.85 By contrast, Mad2 haploinsufficiency either directly promotes chromosome missegregation and tumorigenesis86 or predisposes cells to carcinogen-induced malignant transformation.87 It seems that a particular balance of SAC proteins may confer benefits for centrosome clustering, tumorigenesis, or just survival, in a cell context-dependent manner. Overexpression of SAC proteins may provide not only more time for clustering, thereby promoting cancer cell survival, but also low-grade aneuploidy and CIN due to increased merotely.63 Alternatively, small decreases in SAC protein levels and/or activity may result in a weakened rather than non-functional SAC, also causing chromosome-segregation errors, CIN, and low-grade but survivable aneuploidy. Further research is needed to clarify cell line-specific differences in SAC protein expression and their impact on centrosome clustering and clinical outcomes.

Intriguingly, the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC) and some of its targets are required for clustering in certain human cancer cell lines that exhibit centrosome amplification.61 The CPC comprises four proteins: the SAC-associated enzyme Aurora B and three of its nonenzyme regulators, INCENP, survivin, and borealin. This complex is responsible for promoting the correction of non-bioriented attachments such as syntely and merotely.70 Knockdown of any of the CPC members inhibits clustering and spindle bipolarity in oral squamous cell UPCI:SCC114 cancer cells.61 It remains unclear whether the CPC mediates clustering through its usual function of misattachment correction or whether it serves an additional role. One attractive hypothesis is that the CPC effects clustering via its action on certain targets, namely proteins involved in microtubule–kinetochore attachment and sister-chromatid cohesion. Knockdown of CPC targets HEC1, SPC24, or SPC25 (three of the four Ndc80 complex proteins) inhibits clustering.61 The Ndc80 complex grasps microtubule plus-ends at the kinetochore and stabilizes their association.88 Following Ndc80 knockdown, UPCI:SCC114 cells fail to cluster centrosomes and arrest in metaphase, indicating that sufficient tension across the kinetochore is necessary for clustering.61 Knockdown of other proteins required for sensing or generating tension, including CENPT, sororin, and SGOL1, similarly results in clustering inhibition and arrest, strongly suggesting that loss of tension at sister kinetochores causes centrosome declustering. A recurring theme throughout the literature is that a delicate force balance is necessary for the execution of clustering, so it is intuitive that disruption of forces at the kinetochore would impact clustering. More work is required to shed light on the molecular details of the role of kinetochore forces on centrosome coalescence.

Actin' in concert: Actin, cell adhesion and polarity proteins collaborate in centrosome clustering

Actin is an indispensible and multifaceted component of the centrosome clustering process. F-actin depolymerization inhibits clustering in Drosophila S2 cells and various human cancer cells with extra centrosomes.6 Furthermore, clustering is suppressed in S2 cells by knockdown of various actin-regulating genes, such as those encoding Form3 (human INF2), Rho1, tankyrase, and CG6891 (human COTL), confirming the role of actin in clustering. One mechanism, whereby actin promotes clustering, is by mediating cortex-oriented centrosome migration during mitosis – a process that is dramatically impaired upon actin depolymerization. Cortical ‘cues' established during interphase direct the positioning of the mitotic spindle and centrosomes during mitosis.89 Despite the anonymity of most of these cues, it is evident that interphase cell-adhesion pattern contributes to their establishment within the cortical actin meshwork. For instance, plating breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells with amplified centrosomes on a fibronectin micropattern with a single long axis results in spindle orientation along this axis, whereas plating on an ‘O' shaped micropattern results in random spindle orientation.89 Cells plated on a micropattern with a single long axis, but treated with an inhibitor of cortical asymmetry, are less able to align their spindle along this axis89 or to cluster centrosomes.6 Altogether, these experiments suggest a crucial role of interphase cell-adhesion pattern in the asymmetric distribution of cortical cues (e.g., at opposite cellular poles) to promote centrosome positioning, clustering, and consequent spindle bipolarity.

Cortical actin not only provides a platform for the cortical cues, but it is also involved in setting up the cues during interphase. In plated cells, the interphase adhesion pattern produces a corresponding pattern of actin-based retraction fibers, at the cortical ends of which accumulate the cues.90, 91 When these cells round up during mitosis, most focal adhesions are endocytosed but retraction fibers persist, retaining a memory of interphase cell-adhesion pattern.89 Cells that set up a bipolar rather than isotrophic pattern of retraction fibers during interphase are more successful in clustering centrosomes.6 Furthermore, various cell polarity and adhesion proteins are required for clustering in partnership with actin.6, 92 As the spotlight now focuses on the action at the cell cortex, an exciting domain for future research would be to further tease out the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton on the one hand and focal adhesion components, cell polarity proteins, cortical landmarks, and force generators on the other. Such studies will better define how these molecular players coordinately shape the forces exerted on centrosomes.

Aerialists on the microtubule trapeze: microtubule-binding proteins regulate centrosome clustering

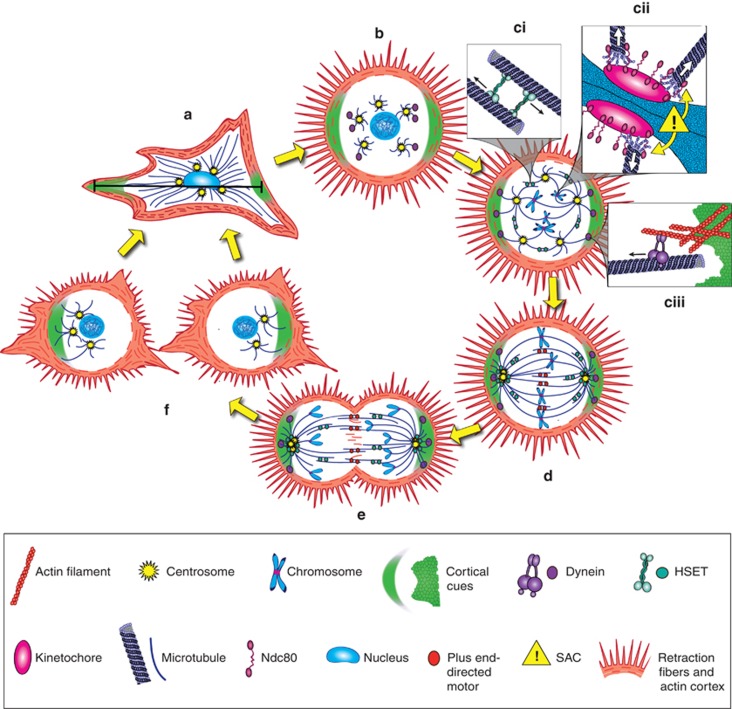

Recent studies have uncovered that multitudinous microtubule-binding proteins, including MAPs and microtubule motors, have an integral role in clustering. We have fashioned a model of clustering mechanisms (Figure 2) that incorporates some of these proteins along with the SAC, actin, cortical cues, and cell-adhesion proteins. Ultimately, our model of global clustering mechanisms strives to communicate how we envision this process occurs, despite present gaps in knowledge and unresolved paradoxes. The following section summarizes the contributions of microtubule-binding proteins to centrosome clustering.

Figure 2.

Global centrosome clustering mechanisms. (a) During interphase, cell adhesion geometry results in establishment of a pattern of cortical cues, which are preferentially distributed at the termini of the cell's long axis (black line). (b) When the cell rounds up for mitosis, actin-rich retraction fibers retain a memory of the cell's interphase adhesion pattern and maintain contacts with the substratum. Microtubule dynamic instability increases. (c) During prophase, astral microtubules probe the cytosol, making contacts with other microtubules, chromosomes, and the actin-rich cortex. (i) HSET may localize between antiparallel astral microtubules. Minus-end directed movement of HSET would thus promote centrosome coalescence. (ii) Astral microtubules are captured at kinetochores by the Ndc80 complex, thus forming kinetochore microtubules. Low-tension attachments activate the SAC, which provides time to correct the errors. By contrast, merotelic attachments are poorly sensed by the SAC and may persist. (iii) Dynein is delivered to the actin-enriched cortex preferentially in the vicinity of cortical cues, which are concentrated at opposite cellular poles. Cortical dynein then captures astral microtubules, and minus-end directed movement of dynein exerts tension that pulls centrosomes to the poles. (d) Tug-of-war between kinetochore microtubules and chromosomes results in alignment of chromosomes along the metaphase plate, although some chromosome lagging occurs, signifying that the cellular milieu is in some way abnormal for attachment. Tug-of-war between dynein, HSET, and other microtubule motors results in a net force that tends to pull some of the centrosomes to one pole and some to the other. Owing to their common final destination, each group of centrosomes forms a cluster. (e) Attainment of the requisite tension or stretch across kinetochores satisfies the SAC and initiates anaphase onset. Sister chromatids separate, although some missegregation occurs. (f) Daughter cells experience low-grade aneuploidy, permitting survival and possibly promoting tumorigenic phenotype

HSET

The Kinesin-14 family member, HSET (also known as KIFC1), a minus end-directed microtubule motor, has a critical role in centrosome clustering in some cell lines. Human HSET localizes between microtubules within the mitotic spindle.93, 94 HSET inhibition has no significant impact on bipolar anaphase or cell viability in human BJ fibroblasts, which exhibit virtually no centrosome amplification (∼1%),95 as well as mouse NIH-3T3 fibroblast and human MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which exhibit only ‘low-level' centrosome amplification.6 However, in cells with a higher incidence of centrosome amplification, such as isogenic tetraploids of the aforementioned cell lines or MDA-MB-231 cells, bipolar anaphase is inhibited and viability compromised by HSET knockdown.6 These data suggest that the presence of a ‘normonumerary' centrosome complement partly masks the requirement for HSET in spindle organization. Although HSET appears to serve no vital function when centrosome number is normal, the minus-end-directed motor was originally identified in embryonic mouse brain; consequently, the possibility that the protein may serve a non-redundant function during embryogenesis cannot be excluded.96

Although HSET knockdown in HeLa cells does result in a minor attenuation of spindle pole focusing, central spindle stability, and microtubule density, along with a mild augmentation of spindle breadth, the occurrence of a bipolar anaphase remains unimpeded.94 HSET inhibition also results in shortening of the spindle in HeLa cells, suggesting that HSET promotes spindle lengthening and pole separation. These results suggest that, at least in HeLa cells, HSET resides between parallel rather than anti-parallel microtubules. When a motor protein walks toward the minus-end of one microtubule, carrying a parallel microtubule as its cargo, spindle lengthening and thus spindle pole separation are achieved.97 However, other data emphasize that HSET may reside between antiparallel microtubules because it promotes spindle pole coalescence. For instance, HSET knockdown in cells with centrosome amplification results in pole separation, which antagonizes centrosome clustering into two polar groups.6 Moreover, HSET has been shown to antagonize the pole-separating activity of Eg5 in human pancreatic cancer CF-PAC1 cells.93 When Eg5 alone is knocked down, monopolar spindles form, suggesting that unopposed HSET activity results in excessive inwardly directed force. Simultaneous knockdown of both Eg5 and HSET restores spindle pole separation in majority of cells. Thus, HSET contributes to centrosome coalescence, and we envisage that HSET may accomplish this task by cross-linking and sliding antiparallel microtubules, as depicted in Figure 2. The case may be that HSET preferentially cross-links and slides antiparallel microtubules for clustering just before metaphase, but then it facilitates spindle pole separation through parallel microtubules during anaphase, although mechanistic details are lacking for this model.

In normal cells, the two centrosomes mask the requirement for HSET in normal spindle biogenesis. In certain transformed cell lines, HSET and NuMA play overlapping and therefore redundant cellular functions, in which case HSET may be non-essential for centrosome coalescence.6, 98 Differential dependence on HSET may indicate that various cell types have evolved distinct clustering mechanisms. Owing to the seemingly nonessential role of HSET in nontransformed human cells, HSET offers immense promise as a novel chemotherapeutic target for ‘centrosome-rich' cancers, including those of the breast, prostate, bladder, colon, and brain.

Dynein

The role of dynein in centrosome clustering appears to be complex and somewhat elusive. In some cancerous (UPCI:SCC114 oral squamous cells) and noncancerous (Colcemid-treated or hMps1-overexpressing HEK293) cells with supernumerary centrosomes, displacement of dynein from the spindle results in centrosome declustering.99 Thus, it appears that spindle-localized dynein is required for centrosome clustering in these cell lines. However, when human keratinocytes and fibroblasts are transfected with HPV16 E7 protein, which triggers centrosome amplification and dynein delocalization from the spindle, centrosome clustering is not inhibited.100 Thus, in some cell lines, dynein localization to the spindle is dispensable for clustering. Similarly, in Drosophila S2 cells, dynein knockdown does not impact clustering.6, 101 These data suggest that dynein may not be required at all for clustering in some cell types. Furthermore, when UPCI:SSC114 cells are treated with the centrosome-declustering drug griseofulvin, dynein is not delocalized from the spindle.8 Similarly, in HeLa cells infected with Chlamydia trachomatis (a bacterium that promotes centrosome amplification, clustering inhibition, and possibly cervical cancer development), centrosome clustering is suppressed even though dynein remains spindle-localized.102 Therefore, spindle localization of dynein is insufficient for centrosome clustering in the presence of griseofulvin or C. trachomatis. Altogether, these studies suggest heterogeneity in clustering mechanisms across species and between human cell types, both transformed and nontransformed.

The prediction that dynein may have a role in centrosome clustering would be commensurate with dynein's extensive involvement in mitotic progression, centrosome assembly and localization, spindle organization, and positioning. Dynein at the kinetochore may be involved in kinetochore–microtubule attachment and SAC silencing.103 The dynein/dynactin complex not only transports a variety of proteins (including several others that promote microtubule nucleation) to the centrosome104, 105, 106, 107, 108 but also nucleates microtubules itself.109 Dynein/dynactin is also necessary for centrosomal retention and focusing of microtubules, regulation of mitotic spindle positioning and length, and migration of interphase cells.110, 111, 112

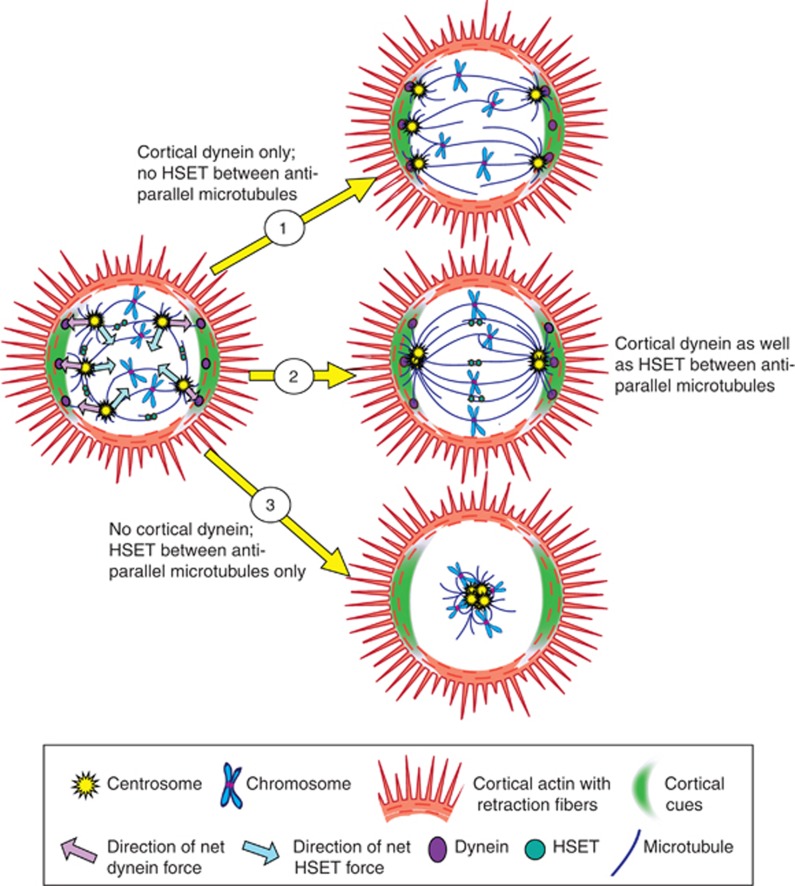

To conjecture how dynein might contribute to clustering, insight can be gained from current models describing how dynein positions centrosomes and the spindle in nontransformed cells with normal centrosome numbers. In one model, dynein/dynactin is delivered to the cortex during mitosis by microtubule plus-ends.112, 113 Cortex-anchored dynein then walks along astral microtubules causing the microtubules to slide along the cortex, pulling centrosomes and the spindle toward the cellular periphery.112, 114, 115 The final position of each centrosome is determined by the balance of pulling forces directed outward by dynein and other outwardly-pulling motors (e.g., myosin) versus inward by other motor proteins (e.g., HSET). In cells with supernumerary centrosomes that exhibit clustering, the net force exerted on each centrosome by motor proteins may point to one or the other of two poles. Nonhomogenous distribution of dynein/dynactin, as has been found in HeLa cells,116, 117 and/or cortical cues91 could orient the force vectors toward one or the other pole. Clustering would then be accomplished by virtue of the various centrosomes having a common final destination. The shared roles of dynein and HSET in clustering are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cooperation of cortical dynein with HSET. Microtubule motors generate outwardly and inwardly-directed forces (the directions of which are indicated by purple and light blue arrows, respectively) to accomplish centrosome clustering. (1) Loss of HSET and other inwardly-directing motors (e.g., spindle dynein) results in declustering owing to unopposed cortical dynein-mediated pulling toward cortex. (2) The pole-coalescing force generated by HSET partially antagonizes the pole-separating force generated by dynein. The balance of forces directs centrosomes to one of two poles. (3) Loss of cortical dynein is theorized to result in collapse of the spindle to a single focus owing to unopposed activity of HSET between anti-parallel microtubules

ILK

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a multifunctional protein that works at two sub-cellular locations. Firstly, it localizes to focal adhesions where it regulates the actin cytoskeleton. Then, ILK localizes to centrosomes and modulates the mitotic apparatus from there.118, 119 Among its various mitotic effects, ILK is necessary for the interaction between two microtubule-binding proteins, TACC3 and ch-TOG.119 In breast cancer cell lines that exhibit centrosome amplification, ILK inhibition suppresses clustering via a mechanism that is independent of its role in focal adhesions, but rather requires TACC3 and ch-TOG.92 The Drosophila TACC3 homolog, D-TACC, is also necessary for clustering in S2 cells.6 D-TACC associates with and stabilizes both the plus- and minus-ends of astral and spindle microtubules.120 Mammals possess three TACC proteins, one of which is crucial for clustering.92 TACC3 localizes to the centrosome and spindle microtubules during mitosis and, like D-TACC, it regulates the length and number of spindle microtubules.120 TACC proteins recruit the MAP ch-TOG to the centrosome where they form a complex;118, 120 however, ch-TOG promotes polymerization of microtubule plus-ends and antagonizes their depolymerization by MCAK.121 TACC3 and ch-TOG are required for clustering in human breast BT549 and prostate cancer PC3 cells.92 Additional work is required to elucidate the details of how the ILK-TACC3-ch-TOG triad cross-talks with other components of the clustering machinery in space and time.

Relying on instability: microtubule dynamicity is important for clustering

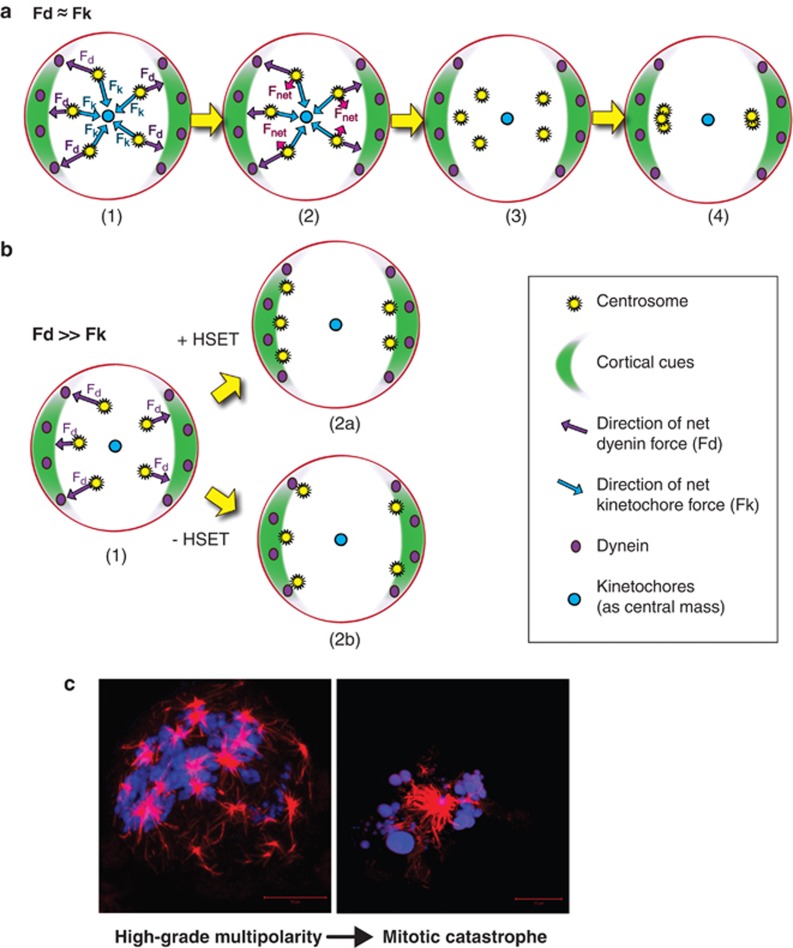

In recent years, research from a few groups including ours has turned the spotlight onto a property of microtubules that is central to their biological function, viz, their dynamic instability, as a key requirement for effective clustering of supernumerary centrosomes. Treatment of cells exhibiting amplified centrosomes with drugs that gently attenuate microtubule dynamicity, such as griseofulvin8 or bromonoscapine,122 induces declustering of supernumerary centrosomes, leading us to postulate that microtubule dynamicity is an important requisite for centrosome clustering. Although centrosome declustering drugs are very different in many respects – for instance, griseofulvin is an antifungal whereas bromonoscapine is a derivative of the antitussive drug, noscapine – the attribute they share is the ability to subtly attenuate microtubule dynamic instability and selectively kill cancer cells. A recurring theme throughout studies of spindle and centrosome positioning is that balancing various cellular forces is crucial for proper alignment and, in many cases, perturbing any one force has dramatic consequences. We therefore propose that microtubule dynamic instability provides another vital force to the balance needed for pseudo-bipolar centrosome clustering. Indeed, microtubule depolymerization can generate a force 10 times greater than that of a microtubule motor protein.123 The force of microtubule plus-end depolymerization has a crucial role in generating the tension that pulls a chromatid from its sister.124, 125, 126 In fact, in fission yeast, minus end-directed motor proteins are entirely dispensable for poleward motion of chromosomes – the force generated by microtubule depolymerization is sufficient.127

In our view, the force of K-fibers pulling the kinetochore must be complemented by an equal and opposite force of the kinetochore pulling K-fibers and hence the centrosome. As a result, microtubule depolymerization at the kinetochore must exert tension on centrosomes that is directed away from the cortex. Depolymerization of astral microtubules (which would result in cortex-directed motion) should be less impactful because there does not seem to be a mechanism to harness the work of depolymerization at the cortex like there is at the kinetochore (discussed next). As chromosomes are located within the center of the cell during early mitosis, the tension of K-fiber depolymerization is, more specifically, directed toward the cell-center. Our speculative model, illustrated in Figure 4a, depicts how we envisage this ‘inwardly-rectifying' tension from depolymerization contributes to pole-focusing. Although the force of K-fiber depolymerization alone is unlikely to be sufficient for clustering, it seems likely that it is necessary in cancer cells for clustering. If the inwardly rectifying force at kinetochores is insufficient, as illustrated in Figure 4b, forces directed outward to the cortex are unchecked and the centrosomes are scattered. Other inwardly directed forces, such as those contributed by HSET, are hypothesized to partially rescue clustering.

Figure 4.

Kinetochore tension as a crucial centrosome clustering mechanism. (A) Model of kinetochore-facilitated clustering: (1) Outwardly-directed, dynein-mediated tension, Fd (direction indicated by purple arrows), is partly offset by inwardly-directed, kinetochore-mediated tension, Fk (direction indicated by cyan arrows). (2) The sum of the forces, Fnet (direction indicated by magenta arrows), is directed to one or the other pole. (3) As a result, centrosomes are brought closer together, although kinetochore-mediated tension alone is probably insufficient to overcome outwardly-directed forces. (4) HSET between antiparallel microtubules provides further inwardly-directed tension, permitting tight clustering. (b) Model of declustering without kinetochore-generated tension: (1) Without tension at the kinetochore, dynein is unopposed. (2) As a result, centrosomes are pulled toward the cortex, and (a) if HSET is present, some pole-focusing occurs, although this is insufficient to cause centrosomes to coalesce; however, (b) without HSET, complete declustering results. (c). Induction of robust declustering results in multipolar spindle formation and cell death. On the left, a human prostate cancer PC3 cell exhibits severely high-grade multipolarity. On the right, a multipolar cell of the same line succumbs to mitotic catastrophe. (microtubules=red; DNA=blue)

There is ample empirical evidence to support the idea that tension at the kinetochore is a crucial clustering mechanism. There has recently been identified a host of proteins necessary for clustering in oral squamous cancer UPCI:SCC14 cells.61 Among these were many proteins involved in generating and/or sensing tension at the kinetochore. For instance, clustering was inhibited by knockdown of certain Ndc80 proteins (viz, HEC1, SPC24, and SPC25) and shugoshin. The Ndc80 complex, part of the outer kinetochore, is involved in not only capturing kinetochore microtubule plus-ends but also coupling the force of their depolymerization to chromosomal movement.128 Shugoshin protects sister-chromatid cohesion during early mitosis, which is necessary to generate tension across the kinetochore, and also senses this tension.129 Knockdown of SPC24 in UPCI:SCC14 cells results in decreased interkinetochore distance, which is an indication of decreased tension. Likewise, loss of shugoshin produces decreased interkinetochore distance as well as increased labeling of kinetochores with BubR1 (BubR1 upregulation is not observed in SPC24 knockdowns because SPC24 is required for BubR1 retention at the kinetochore). Altogether, these experiments demonstrate the importance of kinetochore tension in clustering.

Finally, more support for the tension hypothesis of centrosome clustering comes from our studies of declustering drugs. Treatment of HeLa cells with bromonoscapine122 and MCF-7 cells with griseofulvin130 results in upregulation of BubR1, implying a loss of tension across the kinetochore or an absence of attachment to one or more kinetochores.122 Clearly, in cells with supernumerary centrosomes, microtubule dynamicity promotes transkinetochore tension, which appears necessary for the overall force balance required for centrosome clustering. Mild attenuation of dynamic stability in noncancerous cells appears to be harmless, as griseofulvin and bromonoscapine are apparently nontoxic to healthy cells. We speculate that clustering mechanisms may be like a ‘house of cards' or a ‘house built on the sand,' more delicate and susceptible to relatively minute perturbations of the force balance. By contrast, healthy cells may either possess a number of redundant fail-safe mechanisms or simply not require such precision in force balance as they have two centrosomes during mitosis. Moreover, different cellular processes may exhibit disparate thresholds for inhibition by microtubule stabilization. For instance, some processes, perhaps unique to cancer cells, may be inhibited by the slightest degree of microtubule stabilization, whereas other normal cellular processes may be more robust in withstanding dynamicity perturbations. The threshold for inhibiting clustering might be very low as compared with that for disrupting quotidian cellular activities. Therefore, we believe that drugs which selectively trigger centrosome amplification and also cause persistent declustering in cancer cells are invaluable tools in our anti-cancer arsenal.

In summary, centrosome clustering utilizes processes present in all normal cells, seizing and deploying these mechanisms for the purpose of managing extra centrosomes and appropriating the side benefits of tumorigenesis. Cancer cell lines differ in detail regarding the precise clustering mechanisms used and clustering efficiency, which probably reflects the presence of differential selection pressures that shape tumors at various stages of their progression.

Disperse and Destroy: Induction of Spindle Multipolarity as an Attractive Anticancer Strategy

Too many centrosomes may prove bane or boon to cancer cells depending on whether the cell is able to cluster them neatly at opposite poles. Clustering may confer survival advantages and promote malignancy by predisposing the cell to CIN via merotelic microtubule–kinetochore attachment and genome missegregation.63, 64 When ‘low-grade' (i.e., survivable) missegregation results in the loss of a gene that promotes faithful chromosome segregation and maintenance (or gain of another copy of a gene that disturbs these processes), then the cell acquires CIN – essentially, the ability to shuffle its genome until a stable, malignant phenotype is procured.131 By contrast, in the absence of clustering, supernumerary centrosomes result in spindle multipolarity, which may cause aneuploidy of a mortally high grade. Alternatively, multipolar cells may arrest in mitosis and succumb to death via other mechanisms,63, 122 as depicted in Figure 4c. Given the lethality of the multipolar state, induction of high-grade spindle multipolarity constitutes a novel chemotherapeutic strategy whose efficacy holds much promise. Moreover, declustering of supernumerary centrosomes to achieve multipolarity should specifically target cancer cells and pose no apparent threat to most healthy tissues, unlike the majority of current anticancer remedies, drugs and radiation alike. Understanding the mechanisms by which the few known declustering agents operate can pave the way for rational design and synthesis of cancer cell-specific and thus ‘kinder and gentler' chemotherapy.

Agents of selective destruction: declustering chemotherapeutics

Griseofulvin

The nontoxic antifungal, griseofulvin, induces declustering in various human cancer cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner.8 Griseofulvin has garnered much attention for its anticancer potential, as it suppresses proliferation of tumor cells at doses that are nontoxic to nontransformed cells (viz, normal human fibroblasts and keratinocytes). The antiproliferative effect of griseofulvin is correlated with both its antimitotic action and its ability to induce declustering. Among several 2′-substituted derivatives of griseofulvin, the one with the highest potency also has the greatest ability to induce declustering, suggesting that declustering contributes to both inhibition of mitosis and cell proliferation, although noncorrelative studies are needed to validate this possibility. The precise mechanism by which griseofulvin accomplishes declustering remains largely unexamined; however, a novel idea is that attenuation of microtubule dynamicity may vitiate clustering ability and thereby execute declustering. Griseofulvin suppresses dynamic instability independently of MAPs and does so at doses below those necessary to cause microtubule depolymerization.132 Griseofulvin may therefore realize declustering by hampering dynamic instability, a mechanism we suspect is integral to centrosome clustering.

Noscapinoids

In line with this notion, bromonoscapine (also known as EM011), a derivative of the nontoxic, poppy-derived antitussive, noscapine, suppresses dynamic instability and centrosome clustering.122 This drug simply dampens microtubule dynamic instability without causing depolymerization, overpolymerization, or otherwise noticeably impacting microtubule ultrastructure. Like griseofulvin, bromonoscapine causes G2/M arrest followed by apoptosis; however, bromonoscapine-treated cells also succumb to death by another pathway: multipolar mitosis.122 Synchronized HeLa cells treated with bromonoscapine experience centrosome amplification followed by declustering and then, if able to overcome mitotic block, proceed to divide in an aberrant fashion to produce multiple, highly aneuploid, inviable daughter cells. Although bromonoscapine induces centrosome amplification in cancer cells, there is no evidence to date that the drug has any untoward effects on centrosome copy number, spindle bipolarity, or the viability of noncancerous cells.133 As a result, it seems that bromonoscapine selectively targets cancer cells for centrosome amplification and declustering. The mechanism by which bromonoscapine attenuates microtubule dynamicity is currently under investigation. Some clues to its modus operandi come from the finding that bromonoscapine impairs plus-end association of the plus-end-tracking proteins, EB1 and CLIP-170.122 Whether the failure of these proteins to plus-end track is a cause or consequence of microtubule stabilization warrants further investigation.

Phenanthrene-derived PARP inhibitors

Some phenanthrene-derived poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors also exhibit cancer cell-specific declustering.134 PARP-1 expression is upregulated in various human cancers135 but downregulated in others,136 suggesting a complex role for this protein in tumorigenesis. Treatment of tumors exhibiting centrosome amplification with the phenanthrene-derived PARP-1 inhibitor, PJ-34, results in clustering inhibition, spindle multipolarity, and death by mitotic catastrophe.134 By contrast, treatment of normal proliferating cells with high drug concentration (i.e., 2–3 times greater than necessary for complete PARP-1 inhibition) for several days has no discernible effect on spindle morphology, centrosome integrity, mitosis, or cell viability. PARP-1 is involved in detection and base-excision repair of DNA strand breaks, initiation of the DNA damage checkpoint, and apoptosis,135 activities not plainly related to clustering. However, PARP-1 has been implicated in centrosome amplification.136 Furthermore, in their screen for clustering proteins in S2 cells, Kwon et al.6 identified a PARP, tankyrase-1, and a putative PARP-16 homolog as molecules critical for clustering. Considering that PARP-1 inhibitors induce declustering, these drugs evince great potential for cancer cell-specific chemotherapy.

High-grade spindle multipolarity: its power and payoff

Given the clinical promise presented by declustering agents such as griseofulvin, noscapinoids, and PARP-1 inhibitors, the next logical step would be to enhance declustering efficacy by designing and quantitatively evaluating analogs of these lead small molecules for their ability to trigger death-inducing spindle multipolarity. Small molecules that trigger the most robust multipolarity would be desirable to minimize the chances of unwittingly producing any progeny that may escape death because they harbor ‘low-grade' tumor-promoting aneuploidy.

A fairly common obligate intracellular bacterium, C. trachomatis, which causes the sexually transmitted disease chlamydia, may also have the potential to shed some light on mechanisms involved in declustering. In host cells, C. trachomatis forms an inclusion that associates closely with the host centrosome, induces centrosome amplification, and somehow inhibits the cell's clustering machinery.102 Given the bacterium's controversial relationship with cervical cancer,137 much may be gained by analyzing its impact on centrosome declustering.

Contrary to present-day cancer treatments, which are notoriously toxic, declustering agents offer the prospect of mitigating chemotherapy-related side effects in a groundbreaking way. Declustering itself should not have any impact on cells that do not rely on clustering (such as normal adult cells), thus providing cancer cell-specific action. As cancer cells rely on centrosome clustering for survival, they represent an Achilles' heel in cancer cells, and this vulnerability can be exploited for chemotherapeutic ends. Given how frequently centrosomes are amplified in cancer cells – and not in adult human cells – agents that induce spindle multipolarity hold tremendous promise as the next generation of cancer cell-selective, non-toxic chemotherapeutics. An interesting avenue for investigation would be to examine whether cancer cells' increased need for centrosome clustering proteins translates into an upregulation of clustering protein expression and/or activity, which might make them invaluable cancer biomarkers. Thus, centrosome clustering mechanisms are attractive theranostic targets that could hold the key to unraveling, as well as subduing, the surreptitious enemy named cancer.

Glossary

- MTOC

microtubule organizing center

- CIN

chromosomal instability

- PCM

pericentriolar material

- γ-TuRCs

γ-tubulin ring complexes

- MAPs

microtubule-associated proteins

- HAUS

Homologous to AUgmin Subunits

- MCM

mini-chromosome maintenance

- SAC

spindle assembly checkpoint

- ORC

origin recognition complex

- PCS

premature chromatid separation

- CPC

chromosomal passenger complex

- ILK

integrin-linked kinase

- PARP

polyADP-ribose polymerase

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by RA Knight

References

- Bignold LP, Coghlan BL, Jersmann HP. Hansemann, Boveri, chromosomes and the gametogenesis-related theories of tumours. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:640–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca TJ, Salmon ED. Welcome to a new kind of tension: translating kinetochore mechanics into a wait-anaphase signal. J Cell Sci. 2010;123 (Part 6:825–835. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, Bakhoum SF, Compton DA. Mechanisms of chromosomal instability. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R285–R295. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle WL, Lukasiewicz K, Salisbury JL. Deregulation of the centrosome cycle and the origin of chromosomal instability in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;570:393–421. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-3764-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti F, Thompson SL, Ravi S, Compton D, Dmitrovsky E. Anaphase catastrophe is a target for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1218–1222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Godinho SA, Chandhok NS, Ganem NJ, Azioune A, Thery M, et al. Mechanisms to suppress multipolar divisions in cancer cells with extra centrosomes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2189–2203. doi: 10.1101/gad.1700908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karna P, Rida PC, Pannu V, Gupta KK, Dalton WB, Joshi H, et al. A novel microtubule-modulating noscapinoid triggers apoptosis by inducing spindle multipolarity via centrosome amplification and declustering. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:632–644. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebacz B, Larsen TO, Clausen MH, Ronnest MH, Loffler H, Ho AD, et al. Identification of griseofulvin as an inhibitor of centrosomal clustering in a phenotype-based screen. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6342–6350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BA, Silk AD, Montagna C, Verdier-Pinard P, Cleveland DW. Aneuploidy acts both oncogenically and as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo R, Hernando E, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, et al. Mad2 overexpression promotes aneuploidy and tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Jin F, Jeganathan KB, van Deursen JM. Whole chromosome instability caused by Bub1 insufficiency drives tumorigenesis through tumor suppressor gene loss of heterozygosity. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA, Raff JW. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA, Stearns T. The centrosome cycle: centriole biogenesis, duplication and inherent asymmetries. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1154–1160. doi: 10.1038/ncb2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen L, Vanselow K, Skogs M, Toyoda Y, Lundberg E, Poser I, et al. Novel asymmetrically localizing components of human centrosomes identified by complementary proteomics methods. EMBO J. 2011;30:1520–1535. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M. Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strnad P, Gonczy P. Mechanisms of procentriole formation. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluder G, Khodjakov A. Centriole duplication: analogue control in a digital age. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:1239–1245. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury JL. Breaking the ties that bind centriole numbers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:255–257. doi: 10.1038/ncb0308-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarek J, Hergert P, Magidson V, Khodjakov A. Control of daughter centriole formation by the pericentriolar material. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:322–328. doi: 10.1038/ncb1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt-Dias M, Glover DM. Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:451–463. doi: 10.1038/nrm2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Centrosome duplication: of rules and licenses. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz KB, Lingle WL. Aurora A, centrosome structure, and the centrosome cycle. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:602–619. doi: 10.1002/em.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duensing A, Duensing S. Centrosomes, polyploidy and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;676:93–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6199-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluder G, Khodjakov A. Centriole duplication: analogue control in a digital age. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:1239–1245. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Assoro AB, Lingle WL, Salisbury JL. Centrosome amplification and the development of cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:6146–6153. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Origins and consequences of centrosome aberrations in human cancers. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2717–2723. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difilippantonio MJ, Ghadimi BM, Howard T, Camps J, Nguyen QT, Ferris DK, et al. Nucleation capacity and presence of centrioles define a distinct category of centrosome abnormalities that induces multipolar mitoses in cancer cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:672–696. doi: 10.1002/em.20532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa K. Oncogenes and tumour suppressors take on centrosomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:911–924. doi: 10.1038/nrc2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderhub SJ, Kramer A, Maier B.Centrosome amplification in tumorigenesis Cancer Lett 2012(in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsou MF, Stearns T. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. 2006;442:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nature04985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RW. An update on cohesin function as a ‘molecular glue' on chromosomes and spindles. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1754–1758. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schockel L, Mockel M, Mayer B, Boos D, Stemmann O. Cleavage of cohesin rings coordinates the separation of centrioles and chromatids. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:966–972. doi: 10.1038/ncb2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou MF, Wang WJ, George KA, Uryu K, Stearns T, Jallepalli PV. Polo kinase and separase regulate the mitotic licensing of centriole duplication in human cells. Dev Cell. 2009;17:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thein KH, Kleylein-Sohn J, Nigg EA, Gruneberg U. Astrin is required for the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion and centrosome integrity. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:345–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarek J, Khodjakov A. Ab ovo or de novo? Mechanisms of centriole duplication. Mol Cells. 2009;27:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Arai H, Fujita N. Centrosomal Aki1 and cohesin function in separase-regulated centriole disengagement. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:607–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Martinez LA, Beauchene NA, Furniss K, Esponda P, Gimenez-Abian JF, Clarke DJ. Cohesin is needed for bipolar mitosis in human cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1764–1773. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchene NA, Diaz-Martinez LA, Furniss K, Hsu WS, Tsai HJ, Chamberlain C, et al. Rad21 is required for centrosome integrity in human cells independently of its role in chromosome cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1774–1780. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons Kovacs LA, Haase SB. Cohesin: it's not just for chromosomes anymore. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1750–1753. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yang Y, Duan Q, Jiang N, Huang Y, Darzynkiewicz Z, et al. sSgo1, a major splice variant of Sgo1, functions in centriole cohesion where it is regulated by Plk1. Dev Cell. 2008;14:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Abian JF, Diaz-Martinez LA, Beauchene NA, Hsu WS, Tsai HJ, Clarke DJ. Determinants of Rad21 localization at the centrosome in human cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1759–1763. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi H, Matsumoto Y, Ikeuchi T, Saya H, Kajii T, Matsuura S. BubR1 localizes to centrosomes and suppresses centrosome amplification via regulating Plk1 activity in interphase cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:2806–2820. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haren L, Stearns T, Luders J. Plk1-dependent recruitment of gamma-tubulin complexes to mitotic centrosomes involves multiple PCM components. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmit TL, Ledesma MC, Ahmad N. Modulating polo-like kinase 1 as a means for cancer chemoprevention. Pharm Res. 2010;27:989–998. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornig NC, Uhlmann F. Preferential cleavage of chromatin-bound cohesin after targeted phosphorylation by Polo-like kinase. EMBO J. 2004;23:3144–3153. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WJ, Soni RK, Uryu K, Tsou MF. The conversion of centrioles to centrosomes: essential coupling of duplication with segregation. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:727–739. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201101109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow JJ, Dutta A. Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nature reviews. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:476–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson RL, Maller JL. Cyclin E-dependent localization of MCM5 regulates centrosome duplication. J Cell Sci. 2008;121 (Part 19:3224–3232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.034702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson RL, Pascreau G, Maller JL. The cyclin A centrosomal localization sequence recruits MCM5 and Orc1 to regulate centrosome reduplication. J Cell Sci. 2010;123 (Part 16:2743–2749. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly AS, Prasanth SG, Siddiqui K, Stillman B. Orc1 controls centriole and centrosome copy number in human cells. Science. 2009;323:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.1166745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha T, Ghosh S, Vassilev A, DePamphilis ML. Ubiquitylation phosphorylation and Orc2 modulate the subcellular location of Orc1 and prevent it from inducing apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119 (Part 7:1371–1382. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R, Fofanov V, Panigrahi A, Merchant F, Zhang N, Pati D. Overexpression and mislocalization of the chromosomal segregation protein separase in multiple human cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2703–2710. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strebhardt K. Multifaceted polo-like kinases: drug targets and antitargets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews. Drug Discov. 2010;9:643–660. doi: 10.1038/nrd3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola D, Zannis-Hadjopoulos M. Comparative analysis of pre-replication complex proteins in transformed and normal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1333–1347. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple JW, Duncker BP. ORC-associated replication factors as biomarkers for cancer. Biotechnol Adv. 2004;22:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaginis C, Vgenopoulou S, Vielh P, Theocharis S. MCM proteins as diagnostic and prognostic tumor markers in the clinical setting. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:351–370. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Incassati A, Wang N, McCance DJ. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 cause polyploidy in human keratinocytes and up-regulation of G2-M-phase proteins. Cancer res. 2004;64:1299–1306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa K. Centrosome amplification, chromosome instability and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, Neben K, Ho AD. Centrosome aberrations in hematological malignancies. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber B, Maier B, Fuchs F, Chi J, Riffel P, Anderhub S, et al. Proteins required for centrosome clustering in cancer cells. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:33ra38. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, Maier B, Bartek J. Centrosome clustering and chromosomal (in)stability: a matter of life and death. Molecular Oncolo. 2011;5:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature. 2009;460:278–282. doi: 10.1038/nature08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silkworth WT, Nardi IK, Scholl LM, Cimini D. Multipolar spindle pole coalescence is a major source of kinetochore mis-attachment and chromosome mis-segregation in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero AA, Martinez AC, van Wely KH. Merotelic attachments and non-homologous end joining are the basis of chromosomal instability. Cell Div. 2010;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Boveri revisited: chromosomal instability, aneuploidy and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:478–487. doi: 10.1038/nrm2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders W. Centrosomal amplification and spindle multipolarity in cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R, Brunk K, Vinadogrova T, Peel N, Franz A, Khodjakov A, et al. Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell. 2008;133:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri T. Ueber den Antheil des Spermatozoon an der Theilung des Eies. Ges Morph Phys München. 1887;3:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nezi L, Musacchio A. Sister chromatid tension and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. Decoding the links between mitosis, cancer, and chemotherapy: the mitotic checkpoint, adaptation, and cell death. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Guo WC, Zhao SH, Tang J, Chen JL. Mitotic arrest defective protein 2 expression abnormality and its clinicopathologic significance in human osteosarcoma. APMIS. 2010;118:222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaoka M, Matsuyama A, Hashimoto H. Aberrant MAD2 expression in soft-tissue sarcoma. Pathol Int. 2008;58:329–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung MK, Cheung HW, Wong HL, Yuen HF, Ling MT, Chan KW, et al. MAD2 expression and its significance in mitotic checkpoint control in testicular germ cell tumour. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando E, Nahle Z, Juan G, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Alaminos M, Hemann M, et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimkus C, Friederichs J, Rosenberg R, Holzmann B, Siewert JR, Janssen KP. Expression of the mitotic checkpoint gene MAD2L2 has prognostic significance in colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:207–211. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Mohri Y, Ohi M, Yokoe T, Koike Y, Morimoto Y, et al. Mitotic checkpoint genes, hsMAD2 and BubR1, in oesophageal squamous cancer cells and their association with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin-based radiochemotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SH, Xu AM, Chen XF, Li DH, Sun MP, Wang YJ. Clinicopathologic significance of mitotic arrest defective protein 2 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1827–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Daigo Y, Aragaki M, Ishikawa K, Sato M, Kondo S, et al. Overexpression of MAD2 predicts clinical outcome in primary lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yin F, Du Y, Du W, Chen B, Zhang Y, et al. MAD2 as a key component of mitotic checkpoint: a probable prognostic factor for gastric cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:793–801. doi: 10.1309/AJCPBMHHD0HFCY8W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze KM, Ching YP, Jin DY, Ng IO. Association of MAD2 expression with mitotic checkpoint competence in hepatoma cells. J Biomed Sci. 2004;11:920–927. doi: 10.1007/BF02254377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jin DY, Ng RW, Feng H, Wong YC, Cheung AL, et al. Significance of MAD2 expression to mitotic checkpoint control in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1662–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jin DY, Wong YC, Cheung AL, Chun AC, Lo AK, et al. Correlation of defective mitotic checkpoint with aberrantly reduced expression of MAD2 protein in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2293–2297. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.12.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Benezra R. Identification of a human mitotic checkpoint gene: hsMAD2. Science. 1996;274:246–248. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobles M, Liberal V, Scott ML, Benezra R, Sorger PK. Chromosome missegregation and apoptosis in mice lacking the mitotic checkpoint protein Mad2. Cell. 2000;101:635–645. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel LS, Liberal V, Chatterjee A, Kirchwegger R, Pasche B, Gerald W, et al. MAD2 haplo-insufficiency causes premature anaphase and chromosome instability in mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;409:355–359. doi: 10.1038/35053094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To-Ho KW, Cheung HW, Ling MT, Wong YC, Wang X. MAD2DeltaC induces aneuploidy and promotes anchorage-independent growth in human prostate epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:347–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciferri C, Musacchio A, Petrovic A. The Ndc80 complex: hub of kinetochore activity. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2862–2869. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery M, Racine V, Pepin A, Piel M, Chen Y, Sibarita JB, et al. The extracellular matrix guides the orientation of the cell division axis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:947–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima F, Nishida E. Spindle orientation in animal cell mitosis: roles of integrin in the control of spindle axis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:407–411. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery M, Jimenez-Dalmaroni A, Racine V, Bornens M, Julicher F. Experimental and theoretical study of mitotic spindle orientation. Nature. 2007;447:493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature05786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding AB, Lim S, Montgomery K, Dobreva I, Dedhar S. A critical role of integrin-linked kinase, ch-TOG and TACC3 in centrosome clustering in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:521–534. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain V, Simerly C, Howard L, Ando A, Schatten G, Compton DA. The kinesin-related protein, HSET, opposes the activity of Eg5 and cross-links microtubules in the mammalian mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:351–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Weaver LN, Ems-McClung SC, Walczak CE. Kinesin-14 family proteins HSET/XCTK2 control spindle length by cross-linking and sliding microtubules. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1348–1359. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler H, Bochtler T, Fritz B, Tews B, Ho AD, Lukas J, et al. DNA damage-induced accumulation of centrosomal Chk1 contributes to its checkpoint function. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2541–2548. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WX, Sperry AO. C-terminal kinesin motor KIFC1 participates in acrosome biogenesis and vesicle transport. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1719–1729. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders WS. Mitotic spindle pole separation. Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:432–437. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90032-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]