Abstract

Objective

Postoperative pain is one of the most common complications of surgery. The pattern of management varies between centers. The current study aimed to study the prescription pattern and the common drugs used in the management of postoperative pain in adult surgical patients at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital (ABUTH; Zaria, Nigeria).

Methods

Following ethical approval, a prospective observational study of consecutive adult patients who had surgery at the ABUTH Zaria was performed from January to December 2005. The data were entered into a proforma and analyzed using the Minitab statistical package.

Results

One hundred and thirty-eight patients were included in the study. The age range was 17 to 80 years, with a mean age of 41 years. One hundred and thirty-two (95.7%) of the prescriptions were written solely by the surgeon or surgical resident; passive suggestions were given by the anesthetists for only six patients (4.3%). Intermittent intramuscular injections of opioids/opiates were prescribed for 126 patients (91.3%), while nine patients (6.5%) received intermittent intramuscular injections with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oral paracetamol was prescribed for six patients (4.3%), while three patients (2.1%) received no postoperative analgesic. Moderate pain was recorded in 48 patients (34.8%), and 90 patients (65.2%) had mild pain 8 hours after their operation before subsequent doses of analgesics were given. More females (81 patients [58.7%]), than males (42 patients [29.7%]) suffered moderate to severe pain. The reported side effects were nausea (reported by 32.6% of patients), dry mouth (21.7%), vomiting (13.0%), and urinary retention (6.5%), with 32.6% of patients experiencing no side effects. The three patients who received no analgesics experienced vomiting as a side effect. Despite the high incidence of pain and other side effects, 108 patients (78.2%) still reported that the methods of postoperative pain management were satisfactory.

Conclusion

Despite recent advances and the development of more effective techniques for postoperative pain control, a high proportion of patients still experience moderate to severe postoperative pain. Intermittent intramuscular injection of analgesic medication remains the mainstay of postoperative pain management at the ABUTH Zaria. Anesthetists should be more involved in postoperative analgesia prescriptions and should include other forms of multimodal pain management in their regimens. With proper application of current knowledge and training, postoperative pain management can be improved.

Keywords: postoperative, pain management, adult surgery

Introduction

Despite recent advances in our understanding of the physiology of acute pain, the development of new opioid and nonopioid analgesics and novel methods of drug delivery, and more widespread use of pain-reducing minimally invasive surgical techniques, postoperative pain remains a challenge for many practitioners.1 Not surprisingly, recent surveys in the United States and Europe have emphasized the insufficient quality of postoperative pain management and the need for further improvements.2,3 The increasing implementation of standardized pain evaluation and treatment protocols and the use of multimodal analgesic techniques are signs that improvements in pain management are likely to continue in the years ahead. The pattern of management varies between centers.

We set out to study the prescription pattern and the common drugs used in the management of postoperative pain in adult surgical patients at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital (ABUTH), Zaria, Nigeria.

Methods

The current paper describes a prospective observational study of consecutive adult in-patients who had surgery at the ABUTH Zaria from January to December 2005. The age, sex, site/type of surgery, type of anesthesia, intra/postoperative analgesia, prescriber, postoperative analgesia, postoperative pain perception, and incidence of side effects were documented.

The incidence of side effects was noted by recovery room and ward nurses who had been trained before the study and were blinded to the type of analgesic used. The patients were assessed for pain using the verbal rating scale (VRS) where a score of 0 = no pain, 1 = mild pain, 2 = moderate pain, and 3 = severe pain. The duration of hospital stay ranged between 3 and 11 days. The data were entered into a proforma and analyzed using the Minitab statistical package (Minitab Inc, State College, PA).

Results

One hundred and thirty-eight patients were included in the study. Patients were aged between 17 and 80 years, with a mean age of 41 years. There were 72 males and 66 females, giving a male:female ratio of 1:1.1. One hundred and thirty-two (95.7%) of the patients received a prescription that was written solely by the surgeon or surgical trainee, with passive suggestions provided by an anesthetist (where the surgeon asks the opinion of the anesthetist about the postoperative pain medication) in six patients (4.3%).

Type of medication

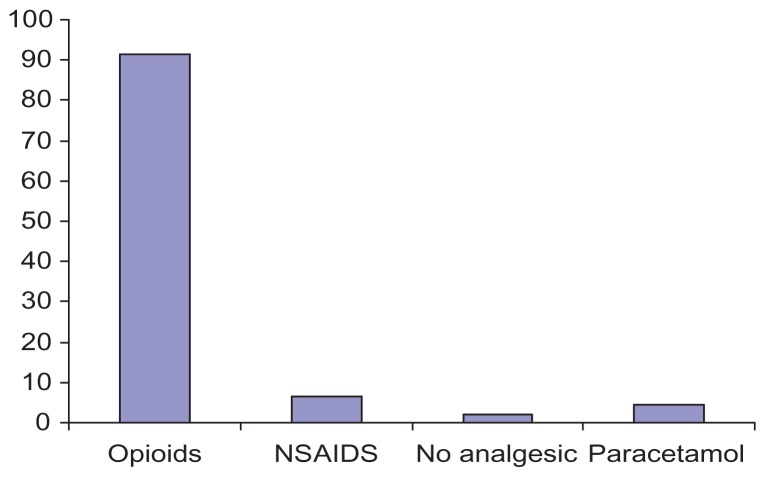

Intermittent intramuscular (IM) injections of opioids (consisting of pethidine [61 patients], pentazocine [53 patients], and tramadol [12 patients]) were prescribed for 126 patients (91.3%), while nine patients (6.5%) received intermittent IM injections of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Oral paracetamol was prescribed for six patients (4.3%), while three patients (2.1%) received no analgesic. Figure 1 shows the drugs prescribed.

Figure 1.

Drugs prescribed to patients following surgery.

Abbreviation: NSAIDS, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

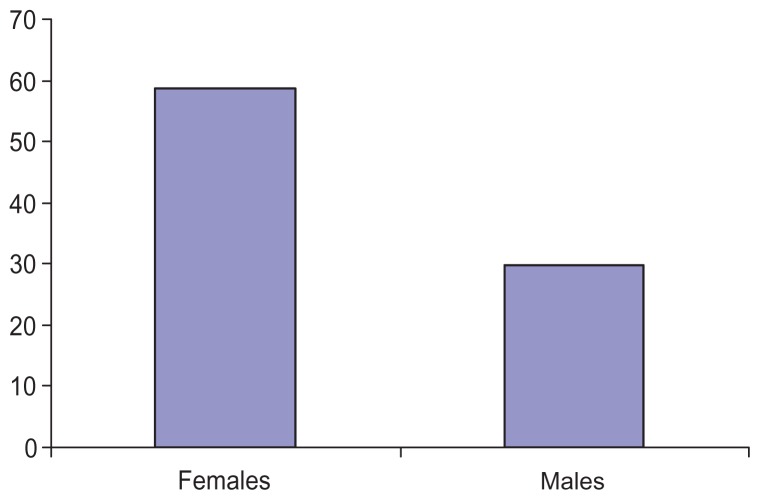

More females (81 patients, 58.7%) than males (42 patients, 29.7%) suffered moderate to severe pain in the immediate postoperative period. Figure 2 shows sex by severity of pain experienced.

Figure 2.

Severity of pain by sex.

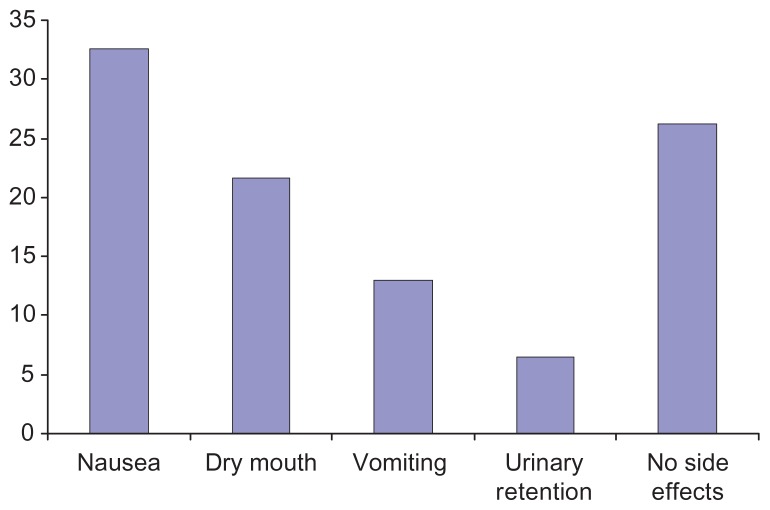

Notes: The incidence of side effects was nausea, 32.6%; dry mouth, 21.7%; vomiting, 13.0%; urinary retention, 6.5%. Some 26.3% of patients experienced no side effects. Three patients received no analgesics, and all experienced vomiting as a side effect.

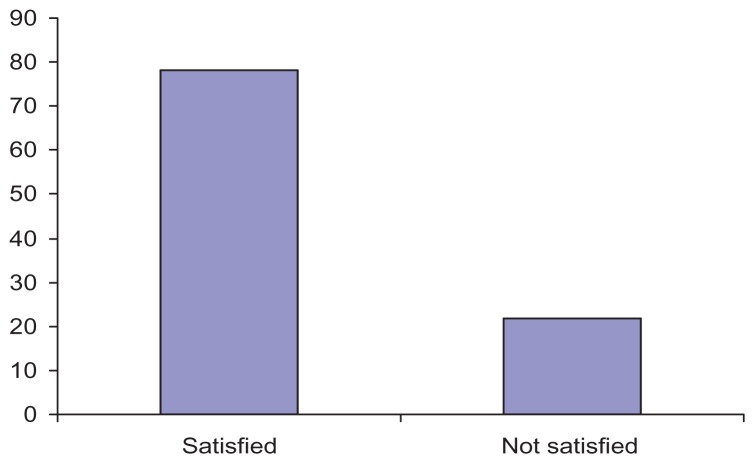

Despite the high incidence of pain and other side effects, 108 patients (78.2%) reported that the methods of postoperative pain management they were provided was satisfactory. Figure 4 shows the level of satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Satisfaction of patients with their postoperative pain management.

Discussion

A high proportion of patients experience moderate to severe postoperative pain despite recent advances in postoperative pain management. Ninety-six percent of the postoperative pain management prescriptions in ABUTH Zaria are made by surgeons alone. Intermittent injections of intramuscular opioids are still the mainstay of management of postoperative pain, unlike in the developed world. This is a major weakness in this practice.

This is similar to findings of a study in Ilorin, Nigeria, which found that all the patients studied had surgeon-prescribed, nurse-administered intermittent IM administration of analgesics for postoperative pain control.4 A similar study in Ibadan, Nigeria found that anesthetists had little or no influence on the prescription pattern or choice of drugs for postoperative pain management.5

In the current study we found that IM injections of opioids consisting of pethidine and pentazocine were prescribed for 91.3% of patients, 6.5% of patients received intermittent IM injections of NSAIDs, and 3.2% received oral paracetamol. In the Ilorin, Nigeria study cited above, pentazocine was prescribed in 86.4% of patients while the remaining 13.6% had tramadol.4

In another study by the authors of the Ibadan, Nigeria study cited above, all postoperative analgesics were intramuscular.6 There was a limited range of drugs to choose from, with only pethidine, pentazocine, and dipyrone available. In another similar study in Kenya, over 97% of patients received pethidine while 2.8% had morphine following major abdominal and thoracic surgery.7

More females (58.7%), than males (29.7%) suffered moderate to severe pain in the immediate postoperative period in the current study. This may be explained by the fact that women experience pain differently from men due to biological, psychological, and social factors.8

Nausea was the most common side effect in this study with 32.6% of patients reporting this, followed by dry mouth (21.7%), vomiting (13.0%), and urinary retention (6.5%), with 32.6% of patients reporting no side effects at all (Figure 3). Although there could be many other reasons for these side effects, these are likely to be opioid-related. The three patients who received no analgesics experienced vomiting as a side effect, which may be related to the type of surgery or anesthetic technique used. In a review article by Werner et al, the most frequently investigated treatment-related side effects were postoperative nausea and/or vomiting (reported in 20 of 25 studies), pruritus (15 of 25 studies), urinary retention (7 of 25 studies), and sedation (7 of 25 studies).9

Figure 3.

Side effects experienced by the patients following surgery.

Despite the high incidence of pain and other side effects, the majority of patients (78.2%) in the current study still reported that their postoperative pain management was satisfactory. This is similar to the report by Kolawole and Fawole, which noted that despite the high incidence of pain, 85.2% of their patients still expressed satisfaction with the level of pain relief.4 The high level of satisfaction expressed by patients despite high levels of pain and side effects may be due to patients being afraid to express their true opinions for fear of negative consequences from the health care providers. It may also be a cultural anomaly related to the Hausa-Fulani people of Northern Nigeria. This is the largest ethnic group in the study area, and the group is known to be stoic – it is normal to express a feeling of well-being despite evidence to the contrary. Bravery and fearlessness are very important to this group. During initiation into manhood, boys hit each other across the chest with sticks enduring tremendous amounts of pain, and many have lost their lives as a result of this ritual.10

For various reasons, effective treatment of acute postsurgical pain presents unique challenges for medical practitioners.11 Adequacy of postoperative pain control is one of the most important factors in determining when a patient can be safely discharged from a surgical facility and has a major influence on the patient’s ability to resume their normal activities of daily living.12 Perioperative analgesia has traditionally been provided by opioid analgesics, as was observed in the current study, but extensive use of opioids is associated with a variety of perioperative side effects (including ventilatory depression, drowsiness and sedation, postoperative nausea and vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, ileus, and constipation) that can delay hospital discharge.13

The concept of multimodal “opioid-sparing” analgesic techniques (so-called balanced analgesia) was introduced more than 15 years ago,11 with the aim of improving analgesia by combining analgesics that have additive or synergistic effects. Multimodal or balanced analgesic techniques involving the use of smaller doses of opioids in combination with non-opioid analgesic drugs (eg, local anesthetics, ketamine, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs) are becoming increasingly popular approaches to preventing pain after surgery.14 There is evidence showing the benefits of multimodal analgesic techniques,15–17 but major surveys have reported that these techniques are underused in clinical practice.2,3 There was a limited use of NSAIDs in the current study, and this is a major weakness in the treatment observed; a combination of lower doses of opioids with NSAIDs could reduce the incidence of side effects, improve the quality of the recovery process, and reduce the hospital stay and postoperative morbidity. Together, this contributes to a shorter period of convalescence after surgery.

Conclusions

Pain remains a significant problem following surgical operations in ABUTH Zaria, and prescribing patterns for postoperative pain therapy in Nigeria appear to have changed little in the last decade. The new treatment modalities, which are being utilized in developed countries, are still not being used in this country. We recommend that anesthetists should be more involved in postoperative analgesia prescriptions and should strengthen postoperative pain management. With the provision of proper facilities, application of current knowledge, training, and re-training, postoperative pain management can be improved even in our low resource setting.

Footnotes

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interests to be disclosed.

References

- 1.White PF. Pain management after ambulatory surgery – where is the disconnect? Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(4):201–207. doi: 10.1007/BF03021503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(2):534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhamou D, Berti M, Brodner G, et al. Postoperative Analgesic Therapy Observational Survey (PATHOS): A practice pattern study in 7 central/southern European countries. Pain. 2008;136(1–2):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolawole IK, Fawole AA. Postoperative pain management following caesarean section in University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital (UITH), Ilorin, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2003;22(4):305–309. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i4.28052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faponle AF, Soyannwo OA. Post-operative pain therapy: prescription patterns in two Nigerian teaching hospitals. Niger J Med. 2002;11(4):180–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faponle AF, Soyannwo OA, Ajayi IO. Post operative pain therapy: a survey of prescribing patterns and adequacy of analgesia in Ibadan, Nigeria. Centr Afr J Med. 2001;47(3):70–74. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v47i3.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocitti EF, Adwok JA. Post-operative management of pain following major abdominal and thoracic operations. East Afr Med J. 2000;77(6):299–302. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i6.46636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray G, Berger P. Pain in women with HIV/AIDS. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner MU, Søholm L, Rotbøll-Nielsen P, Kehlet H. Does an acute pain service improve postoperative outcome? Anaesth Analg. 2002;95(5):1361–1372. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200211000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassey AO. Pray through the 10/40 window: “The Fulani.”. Focus. 2008;3(2):1–4. [ http:www.cmd1040.org/focus/focus%20Fulani.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehlet H, Dahl JB. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1921–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung F, Ritchie E, Su J. Postoperative pain in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(4):808–816. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White PF. The role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of pain after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(3):577–585. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White PF. The Role of Non-Opioid Analgesic Techniques in the Management of Postoperative Pain. [Accessed March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://www.nysora.com/pain_management/3105-the-role-of-non-opioid-analgesic-techniques-in-the-management-of-postoperative-pain.html.

- 15.Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg. 1993;77(5):1048–1056. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199311000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilron I, Orr E, Tu D, Mercer CD, Bond D. A randomized, double-blind controlled trial of perioperative administration of gabapentin, meloxicam and their combination for spontaneous and movement-evoked pain after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(2):623–630. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318193cd1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White PF, Sacan O, Tufanogullari, Eng M, Nuangchamnong N, Ogunnaike B. Effect of short-term postoperative celecoxib administration on patient outcome after outpatient laparoscopic surgery. Can J Anesth. 2007;54(5):342–348. doi: 10.1007/BF03022655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]