Abstract

The types of malocclusions encountered in rodents and lagomorphs are classified. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis are reviewed. Some malocclusions are curable, whereas others can only be controlled. The need to perform a complete oral examination and to find a cause for the condition is stressed, as it will seriously affect the prognosis.

Introduction

Rodents are varied, numerous, and widespread. They are distinguishable by their strong set of continuously growing incisors. Their premolars and molars, on the other hand, are of the brachyodont type, with a set crown and well-formed roots. Of the 1700 rodent species, only 5 (springhaas, Patagonian cavy, capybara, chinchilla, guinea pig) have open-rooted systems that result in continuous growth of all teeth (1); they are classified as full elodonts (2). Chinchillas and guinea pigs are common pocket pets that often present to veterinary facilities in poor health. Rabbits, which are lagomorphs, possess a 2nd set of maxillary incisors, and all their teeth continue to grow throughout their lives. As with chinchillas and guinea pigs, continuous growth of all teeth makes them more susceptible to malocclusions, which, in turn, lead to conditions that affect the animal's health and cause the owners to seek veterinary expertise. This paper describes the malocclusions that are commonly encountered in rabbits, chinchillas, and guinea pigs.

Clinical signs

Several orthodontic conditions exist, but no matter which pathologic process is at work, the clinical signs remain the same: weight loss, anorexia, drooling (“slobbers”) (Figure 1), presence of coarse matter in the stools, incisor overgrowth (Figure 2), facial abscesses (Figure 3), exophthalmos, and ocular discharge (1,3).

Figure 1. A chinchilla with a case of “slobbers.” The wet fur is characteristic of the condition.

Figure 2. Malocclusion resulting in incisor overgrowth.

Figure 3. A large facial abscess in a rabbit. The purulent material in rodents and lagomorphs is caseous, and the mass needs to be removed in total.

Pathology

A few definite processes can be involved and each will be discussed in turn.

Lack of lateral excursion during mastication

The incisors align laterally and mesiodistally (rostrocaudally) and have normal occlusion. The cheek teeth align mesiodistally but not laterally. The marked anisognathism, the diminished lateral excursion of the mandible, or both results in uneven wear of the cheek-teeth occlusal surfaces, leading to the formation of spurs. The mandibular cheek teeth form lingual spurs, whereas the maxillary teeth form buccal spurs (Figure 4). Elongated mandibular spurs can form an arch, trapping the tongue (Figure 5). Elongated maxillary spurs cause lacerations of the cheeks.

Figure 4. A guinea pig in which maxillary spurs extend buccally and end up lacerating the inside of the cheek.

Figure 5. Elongation of the mandibular cheek teeth in a guinea pig resulting in the tongue being trapped, preventing deglutition. The consequence is starvation.

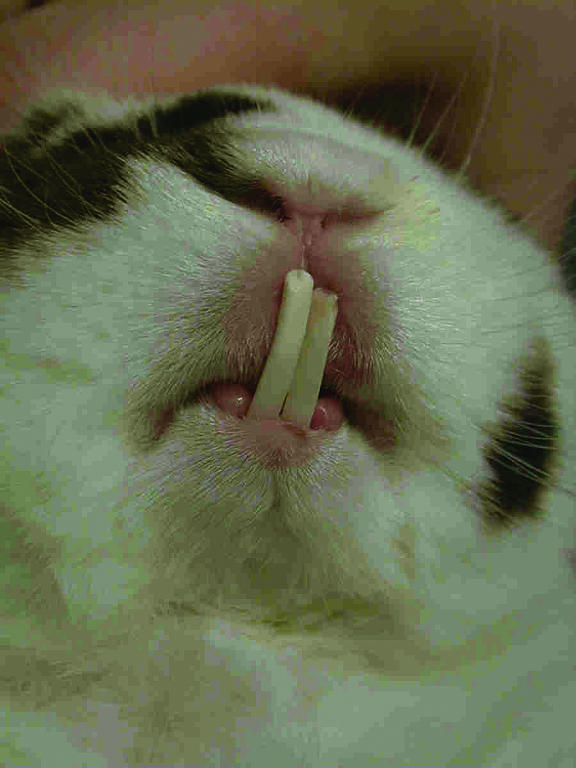

Mandibular prognathism

This condition is most commonly encountered in dwarf rabbits and seems to have a hereditary component (4). The mandibular incisors are situated rostral to the maxillary incisors, a condition called cross bite, and, as a result, quickly overgrow. The maxillary incisors curve backward and upward into the oral cavity, whereas the mandibular incisors elongate rostrally and protrude through the lips (Figure 6). A spur is sometimes present on the mesial mandibular and distal maxillary cheek teeth, and the elongation of the incisors prevents the patient from fully closing its mouth, which allows the cheek teeth to overgrow.

Figure 6. Class III malocclusion or mandibular prognathism is very common in dwarf rabbits.

Reduced amount of daily mastication

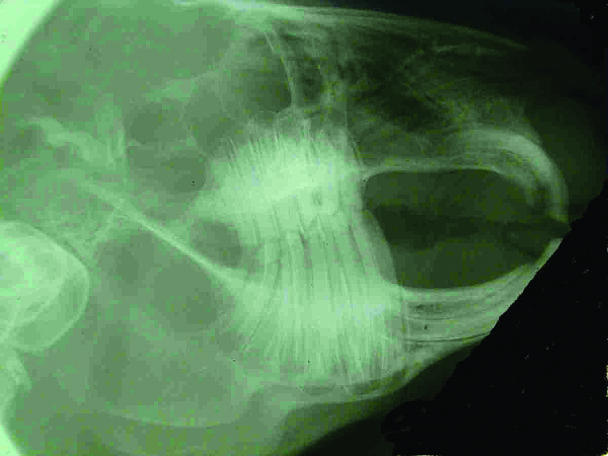

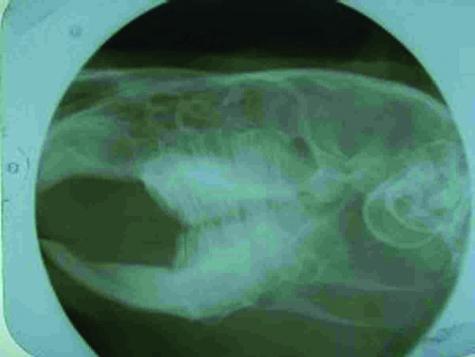

The occlusion in this case is basically sound but the patient is not chewing vigorously enough or long enough. The main cause is dietary. These pets are fed processed, soft food and not enough coarse, abrasive plant material. The teeth are not worn out adequately and overgrow. The patient finds itself stuck with its mouth open (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Lateral radiograph of a rabbit showing how the elongation of the cheek teeth keeps the mouth open.

Treatment

In all 3 scenarios, the teeth overgrow, keeping the mouth open and preventing normal prehension and mastication of food. The treatment is to reestablish normal occlusion. First, one must obtain diagnostic radiographs to determine whether elongation of roots, periodontal disease, osteomyelitis, or periapical abscesses are present. These conditions are sequelae of malocclusion.

Patients having difficulty in masticating have the best prognosis. Treatment involves realignment of the occlusal table and changing the diet to one that is more abrasive, to prevent recurrence.

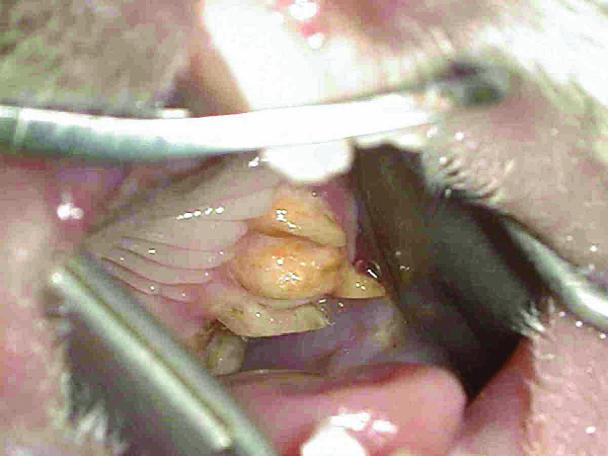

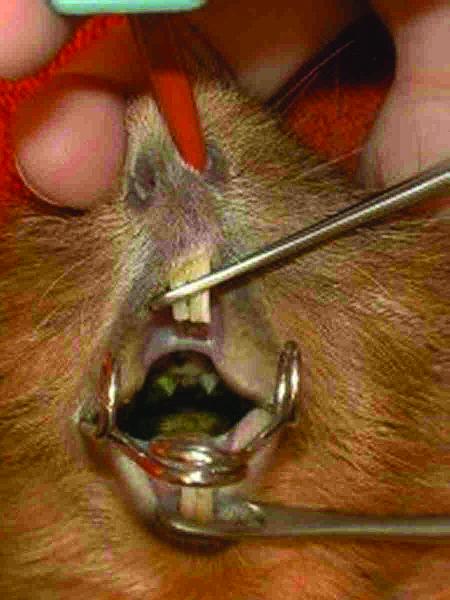

Prognathic patients need to have their incisors extracted to eliminate the malocclusion (Figure 8). Then, the occlusal table is realigned and the patient placed on a rough diet. Cut hay works very well, in that it is prehended by the lips and then processed by the cheek teeth.

Figure 8. The maxillary and mandibular incisor teeth of a rabbit. In rodents and lagomorphs, their extraction requires special equipment and patience.

Patients with marked anisognathism or lack of lateral excursion have the poorest prognosis. Realignment of the occlusal table is only a means of control, not a cure. Its effect is only temporary, and treatment has to be repeated frequently. Placing the patient on a rougher diet will increase the dental wear and help to lengthen the interval between treatments.

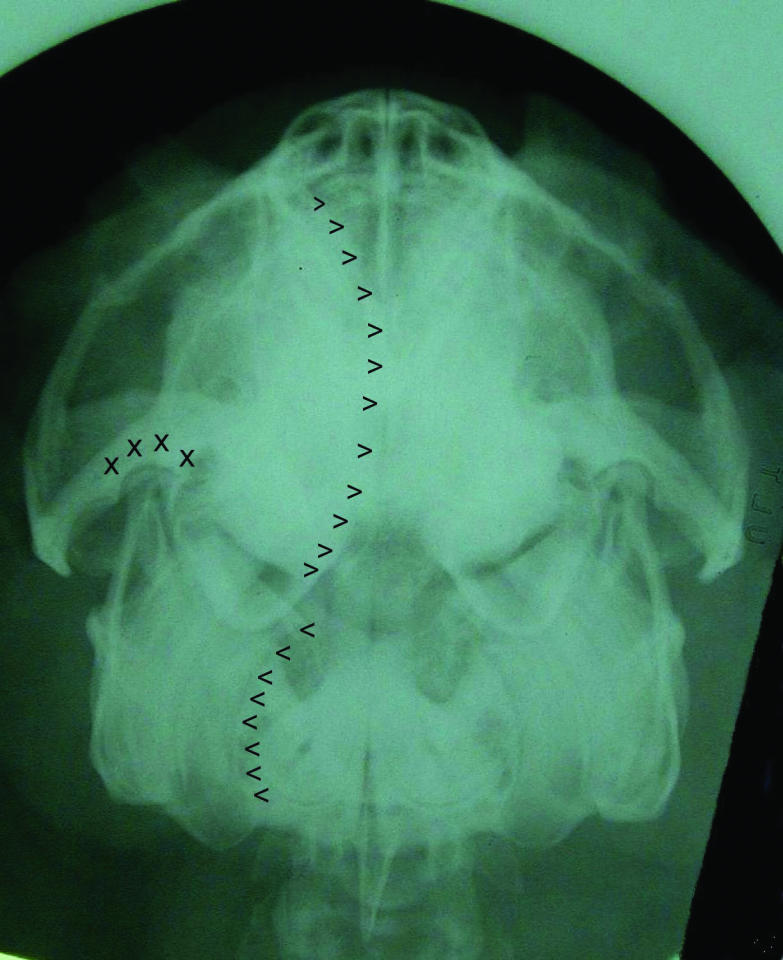

Radiology

Radiographs are essential in order to examine the occlusal plane, and a knowledge of the normal anatomy is fundamental to their interpretation (5,6). Extraoral, nonscreen film is used to obtain lateral and rostrocaudal (Figure 9) views.

Figure 9. Rostrocaudal radiograph of a guinea pig showing the curvature of both upper (>) and lower (<) cheek teeth, as well as the normal slope of the occlusal table. If the alignment is perfect, it provides an excellent view of the temporomandibular (x) joints.

Technique

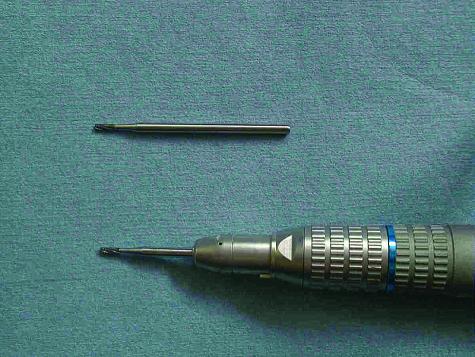

A rodent dental speculum (Rodent mouth gag, J51rg; Jorgensen Laboratories, Loveland, Colorado, USA) (Figure 10) and a set of buccal specula (Cheek dilators, J51rds and J51rd1; Jorgensen Laboratories) (Figure 11) enable the operator to visualize the cheek teeth (Figure 12) and facilitate occlusal leveling. Other equipment that is very useful includes a straight nose cone (Straight attachment, EX-VI E-Type; NSK America Corporation, Schaumburg, Illinois, USA) mounted on a slow-speed handpiece (EX 203; NSK America Corporation), HP burs #558 (SS White Burs, Lakewood, New Jersey, USA) (Figure 13), a high-speed handpiece, and diamond burs (SS White Burs). The high-speed handpiece and diamond burs are used to reduce the crowns of the incisors, which can be accomplished with the patient awake and held firmly on its back. A tongue depressor is introduced behind the incisors to protect the soft tissue while the diamond bur is used to cut the incisors at an angle that will reproduce the normal natural bevel. The use of nail clippers or cutters is not recommended, as the teeth can splinter; the resultant diagonal fractures that extend subgingivally into the pulp, causing dental abscess (1).

Figure 10. Oral speculum for rodents or lagomorphs, which is designed to spread the incisors apart.

Figure 11. Cheek dilators are designed to stretch the cheeks laterally and allow visualization of the cheek teeth. The larger one fits rabbits, whereas the smaller one fits dwarf rabbits, guinea pigs, and chinchillas.

Figure 12. Specula in place showing that the cheek teeth become visible and accessible.

Figure 13. The HP bur #558 by itself and mounted on a straight cone in a slow-speed handpiece.

Leveling the cheek teeth is the equivalent of power floating in horses. It is more complicated and requires the patient to be anesthetized. It is extremely important to use a speculum to visualize the crowns of the teeth to be reduced. A hand dental rasp (J51rr; Jorgensen Laboratories) can be used, but it is slower and there is more chance of trauma to the soft tissues. The tool of choice is a #558 HP bur mounted on the straight-nose cone of a slow-speed handpiece. It is a good idea to split a tongue depressor lengthwise and introduce the halves on the buccal and lingual sides of the teeth to protect the soft tissues while cutting the elongated crowns. With good illumination, the work can be accomplished in a few minutes. Another radiograph should be obtained to verify that enough tooth structure has been removed.

The technique to remove incisors has been described previously in detail (7). In brief, it consists in gently luxating and elevating the incisors by using fine curved instruments (Luxators EX15 and EX16; Cislak Manufacturing, Glenview, Illinois, USA, or Crossley rabbit incisor luxator, J41cr; Jorgensen Laboratories). A 20-gauge hypodermic needle can also be used. Extreme care is required not to break the teeth; even then, sometimes only the shell of the root comes out, leaving the pulp in situ, in which case there is a good chance that the tooth will regrow. Always inform the owner of this possibility before performing the surgery.

Monitoring

Because the teeth continue to grow and erupt, the situation is dynamic. If the procedure that has been undertaken is only bringing control, it will have to be repeated in 4 to 8 wk. If the procedure is curative — for example, with mandibular prognathia or improper diet — a visit should be scheduled for 4 wk postoperatively to examine the state of the oral cavity. Some cases that should have been cured continue to present with elongated cheek teeth, owing to slackening of the masticatory muscles following prolonged stretching. Even though the occlusal table has been realigned, the teeth do not wear, because the mouth “hangs” open (Figure 14). Placing a sling that supports the mandible (Figure 15), worn 12 h a day, in the form of neoprene headgear (Figures 16a, 16b), brings the cheek teeth back into normal occlusion. The sling does not seem to cause any side effects, except for some hair being rubbed away, and has prevented recurrence of malocclusion in several patients (Figure 17). In cases diagnosed early, the harness shows promise for cure, eliminating the need for crown amputations.

Figure 14. This guinea pig is unable to close its mouth at rest because the masticatory muscles have been stretched by the elongated crowns of its cheek teeth.

Figure 15. Guinea pig with headgear in place.

Figure 16. a) Headgear cut out of 1-mm neoprene with Velcro squares as closing system. b) Neoprene headgear closed. Notice that the Velcro squares at on top for easy access. The openings on the sides allow the ears to be passed through.

Figure 16. Continued.

Figure 17. Lateral radiograph of a guinea pig, wearing a headgear, 12 wk after occlusal leveling. Notice that no spurs are visible and that the crowns of the mandibular mesial cheek teeth are the same length as those of the distal cheek teeth. This patient still does not require further treatment. Prior to wearing the headgear, occlusal leveling was performed every 6 wk.

Discussion

Lagomorphs and the 5 rodents have a totally different dentition from dogs and cats; consequently, their malocclusion problems have to be dealt with in an entirely different way. For example, the use of corrective orthodontic appliances is impossible. The operator is facing a dynamic problem: the dental relationships keep changing, because the teeth lengthen daily. Treatment consists of reestablishing anatomic occlusion and eliminating the cause of the malocclusion. Failing to eliminate the cause means that the occlusal leveling will have to be repeated time and time again, placing the patient at risk. This is why it is so important to determine the cause of the malocclusion by means of a complete oral examination, including visualization of the cheek teeth and radiographs of the whole dentition. Discovering the cause is also important for planning the correct treatment and in determining the long-term prognosis. Veterinary dentistry has now reached a point where clipping or filing the incisors is just not enough.

Footnotes

This paper was peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Wiggs RB, Lobprise H. Dental disease in rodents. J Vet Dent 1990;7(Sept):6–7.

- 2.Kertesz P. Veterinary Dentistry and Oral Surgery. London: Wolfe Pbl, 1993:36.

- 3.Turner T. The incidence of dental problems in pet rabbits. J Br Vet Dent Assoc 1996;4:4–5.

- 4.Harcourt-Brown F. Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of dental disease in pet rabbits. In Practice 1997:407–418.

- 5.Crossley D. Clinical aspects of rodent dental anatomy. J Vet Dent 1995;12:131–135. [PubMed]

- 6.Crossley D. Clinical aspects of lagomorph dental anatomy: the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J Vet Dent 1995;12:137–140. [PubMed]

- 7.Crossley D. Extraction of rabbit incisor teeth. Proc Eur Vet Dent Soc Forum 1994.