Abstract

Standard written methods of presenting research information may be difficult for many parents and children to understand. This pilot study was designed to examine the use of a novel prototype interactive consent program for describing a hypothetical pediatric asthma trial to parents and children. Parents and children were interviewed to examine their baseline understanding of key elements of a clinical trial, eg, randomization, placebo, and blinding. Subjects then reviewed age-appropriate versions of an interactive computer program describing an asthma trial, and their understanding of key research concepts was again tested along with their understanding of the details of the trial. Parents and children also completed surveys to examine their perceptions and satisfaction with the program. Both parents and children demonstrated improved understanding of key research concepts following administration of the consent program. For example, the percentage of parents and children who could correctly define the terms clinical trials and placebo improved from 60% to 80%, and 80% to 100% among parents and 25% to 50% and 0% to 50% among children, respectively, following review of the interactive programs. Parents and children's overall understanding of the details of the asthma trial were 14.2±0.84 and 9.25±4.9 (0–15 scale, where 15 is complete understanding), respectively. Results also suggest that the interactive programs were easy to use and facilitated understanding of the clinical trial among parents and children. Interactive media may offer an effective means of presenting understandable information to parents and children regarding participation in clinical trials. Further work to examine this novel approach appears warranted.

Several studies suggest that standard verbal and/or written methods of communicating medical and research information are often inadequate.1–3 Alternative strategies including the use of video technology have been explored with mixed success.4–6 However, the effectiveness of video presentations is limited by their passive and often generalized nature. Interactive computer-based technologies offer the potential to overcome some of these limitations by promoting active participation and allowing individuals to access information that is consistent with their learning styles and abilities.7 8 The theory supporting the effectiveness of computer-based learning is grounded in the concept that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ or, technically speaking, the pictorial superiority effect.9 The pictorial superiority effect has been established in both adults and children; a finding that has practical applications, as studies suggest that visual depictions may be helpful in the retention of material.10

This pilot study was therefore designed to examine the usability and acceptability of two versions of an interactive computer program in explaining a hypothetical clinical asthma trial to parents and children.

Methods

Interactive programs

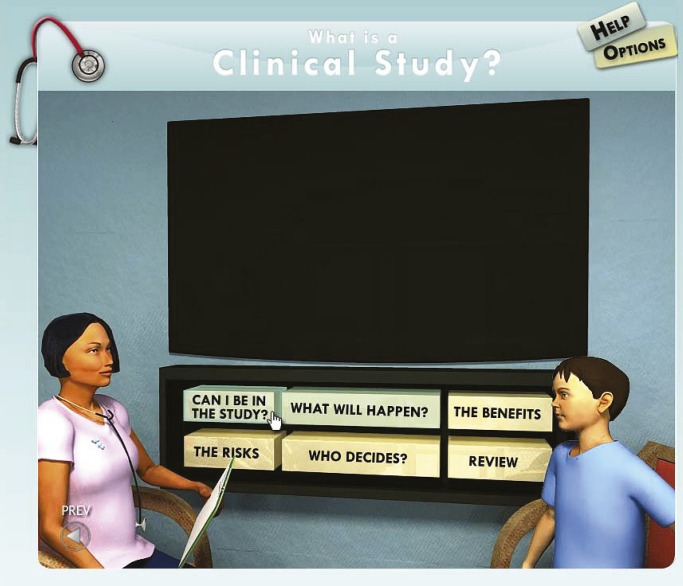

Before evaluation, the interactive modules were reviewed by both experts and lay individuals for accuracy of content and flow. Several iterations were performed before release of the final prototype used in the study. The child/adolescent version of the program used three-dimensional (3D) modelled animated characters (avatars) to present a dialog between a child and doctor in an office setting (figure 1). The doctor presented the child with the opportunity to participate in a hypothetical clinical trial of asthma and the child asked various questions to help explain key concepts. We chose a sham clinical trial for this pilot as a means to evaluate the acceptability and usability of the prototype program, bearing in mind that testing of future versions would require knowledge of a real trial. Despite this, there is strong evidence confirming the ability of simulated studies to accurately predict real behaviors.11 12 The adult version incorporated a mix of live-action elements in an animated 3D office with the doctor explaining the key concepts of a clinical trial directly to the user (parent). In order to obtain the live-action elements the developers utilized green screen technology to place an actor (the doctor) into the 3D office setting. Both versions contained the same basic information although the child's version used simpler language. In both versions the user was required to interact with the program by clicking on different icons to obtain information about the trial, review their understanding of the information, and ‘sign’ a mock consent form. Different modules included: ‘who can be in the trial’, ‘what will happen?’, ‘the benefits’, ‘the risks’, and ‘who decides?’. Finally, there was a review module that summarized all the information presented and tested user understanding of the material.

Figure 1.

Screen shot of the child's version of the interactive computer consent program.

Program evaluations

This study was approved by the University of Michigan's Institutional Review Board. Nine subjects (five parents and four unrelated children, aged 8–14 years) attending one of our hospital's waiting rooms were enrolled. Participants were told only that we were evaluating a new method of providing information about a hypothetical asthma trial but that the child would not actually participate in the trial. Following verbal consent and assent, subjects were interviewed to assess their baseline understanding of the terms: ‘clinical trial’, ‘randomization’, ‘placebo’, and ‘blinded study’ (pre-test). Responses were transcribed verbatim by a trained research assistant and scored as either correct or incorrect based on standard definitions of these terms.

Participants were then given the appropriate parent or child version of the interactive program, preloaded on a laptop computer. Participants were allowed to navigate the program in their own time but the research assistant was available throughout to help and answer questions. Once the subjects had completed the program, they were interviewed using a semistructured format to determine their understanding of the elements of the asthma trial, eg, risks, benefits, purpose, alternatives, etc. Responses were transcribed verbatim by the research assistant and later scored by two independent assessors as either correct or incorrect or graded using a previously used scale based on the Deaconess informed consent comprehension test,13 14 wherein scores of 0, 1, and 2 were assigned based on the participant having no, partial, or complete understanding, respectively. Scores were combined to provide a composite score of understanding (range 0–15, where 15 is complete understanding). In addition, a post-test was administered to re-assess the participants' understanding of the terms presented earlier, ie, randomization, placebo, etc. To further assess understanding, the research assistant scored the subjects' real-time ability to correctly respond (on the first attempt) to various questions or tasks regarding their understanding of the trial and other key concepts (risk, benefits, etc.) that were embedded in the program. Finally, parents and children completed a short survey to obtain basic demographic data and to assess their perceptions of and satisfaction with the quality of the program and presentation. The subjects' perceptions of the interactive program were measured using categorical responses and 0–10 numbers scales.

Sample size considerations and statistical analysis

The study was limited to nine participants (four children and five parents) in compliance with the Office of Management and Budget restrictions on studies involving human subjects in NIH research contracts. Descriptive data were analyzed using frequency distributions. Comparisons between the pre and post-tests were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Interrater reliability was measured using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Results

Five parents (three fathers, two mothers, mean age 44.4 years, range 38–50) and four children (two boys, two girls, mean age 11.0 years, range 8–14) were enrolled. One of the parents had completed high school and the others were college graduates. Four out of five parents reported that they had participated previously in a real clinical trial, whereas none of the children had been in a previous research study.

Understanding

Measures of interrater reliability of the scores revealed excellent correlations for different items (range 0.72–1.00, p<0.05). The percentage of subjects who could correctly define the clinical research terms clinical trials, randomization, placebo, and blinding mostly improved from baseline following administration of the interactive program. For example, the percentage of parents who could correctly define these respective terms increased from 60% to 80%, 20% to 60%, 80% to100%, and 80% to 80% from baseline following administration of the adult program. Among children, the percentage of children who could correctly describe these terms mostly improved from 25% to 50%, 0% to 0%, 0% to 50%, and 25% to 50% following administration of the child's program. These differences were not statistically different.

Table 1 describes the participants' understanding of the purpose of the asthma trial, what would be done, the risks and benefits, and the alternatives to participation. Composite scores for parents' and children's overall understanding of these elements were 14.2±0.84 (0–15 scale, where 15 is complete understanding) and 9.25±4.9, respectively. As another measure of understanding, responses to questions or tasks embedded in the program were documented. Overall, parents were able to respond to questions/tasks correctly (on the first attempt) 90.2% of the time and children 61.1% of the time.

Table 1.

Subjects' understanding of the details of the asthma trial

| ‘None’ n (%) | ‘Partial’ n (%) | ‘Complete’ n (%) | |

| Study purpose | |||

| Parent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Child | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) |

| What would happen | |||

| Parent | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| Child | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Risks | |||

| Parent | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Child | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) |

| Benefits | |||

| Parent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Child | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Alternatives | |||

| Parent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Child | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) |

Perceptions of the programs

Each program took approximately 15 min to complete. Although the majority of parents and children reported being comfortable with computers (9.8±0.45 and 7.0±4.2, respectively, 0–10 scale where 10 is extremely comfortable), all required some (minimal) help in navigating the program. Table 2 describes the subjects' perceptions of the usability and acceptability of the interactive program. As shown, the majority of parents and children were satisfied and, in general, responded very favorably to the program and process. Children, in particular, appeared to enjoy the animation and interactive features and all thought that the program was ‘fun to use’. Four out of five (80%) of parents and all children (100%) reported that if recruited for a real clinical trial in the future that they would like to receive study information using a similar interactive computer program.

Table 2.

Subjects' perceptions of the interactive program

| Parent (n=5) | Child (n=4) | |

| Overall perceived understanding of the asthma trial | 8.4±0.9 | 8.5±2.4 |

| Quality of the trial information | 8.8±1.6 | 8.0±2.8 |

| Ability to follow trial information | 8.4±1.3 | 9.0±2.0 |

| Ease of use of the program | 8.4±1.3 | 10.0±0.0 |

| Satisfaction with the program | 8.2±1.3 | 9.5±1.0 |

| Quality of | ||

| Animation/graphics | 7.4±1.9 | 9.0±2.0 |

| Interactivity | 8.2±1.9 | 10.0±0.0 |

| Speech | 8.4±1.7 | 9.8±0.5 |

| Sound | 8.0±1.2 | 9.8±0.5 |

Scores are based on 0–10 scales where 10 is best.

Data are mean±SD.

Open-ended comments from both parents and children were overall very positive. Parents' comments included: ‘Explained the benefits and risks’, liked ‘the interactive style and flow of information’, ‘visual aids alongside verbal information’. Positive responses from children included: ‘It was fun to interact with and it gave lots of helpful information’, liked ‘the interaction and how it was explained’. The only negative comments came from two parents, one of whom felt that the prototype ‘Moved a little slowly’, and the other who noted that ‘It needs some prompts on some screens’.

Discussion

Given that this was a pilot study and that we were limited by the number of subjects allowed by the NIH contract, there was insufficient power to conduct statistical analyses beyond the simple frequency distributions described herein. However, given that data from previous studies have shown that parents' and children's understanding of consent/assent information using conventional written consent forms was generally poor,2 3 14 these results, albeit preliminary, suggest that interactive media hold promise as an alternative method for improved communication. For example, studies have shown that when using standard written research consent forms, only 58.5% and 52.7% of parents understood the purpose of the study and what would happen to their child, respectively.2 Among children, only 44.1%, 41.9%, and 24.4% had an understanding of the purpose, protocol, and alternatives, respectively, when receiving written information.3 Results from this current study using an interactive program for consent/assent thus compare very favorably with these data that used conventional written forms among similar subject populations. Furthermore, these results suggest that the interactive consent programs used in this study were well received, easy to use, and appeared to facilitate both understanding and learning among parents and children. Children, in particular, enjoyed the interactive nature of the program and the animation and graphics.

In summary, interactive media appear to offer a novel and effective way of providing understandable information to parents and children regarding participation in clinical trials. Further refinement of these programs incorporating input from the parents and children in this study appear to be an appropriate ‘next step’ in the development of this potentially promising approach to optimize the communication of research and medical information.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a contract grant from the National Institutes of Health (HHSN268201000026C) to RL. ART is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health; NICHD (R01 HD053594).

Competing interests: RL is the president and chief medical officer of ArchieMD, Inc. but was funded independently for this project by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. RL was responsible for the development of the interactive prototype but had no involvement in subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. None of the other investigators have any financial, commercial, or other interests in ArchieMD, Inc.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the University of Michigan's Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Klingbeil C, Speece M, Schubiner H. Readability of pediatric patient education materials. Clin Peds 1995;2:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Do they understand? (part I): parental consent for children participating in clinical anesthesia and surgery research. Anesthesiology 2003;98:603–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Do they understand? (part II): assent of children participating in clinical anesthesia and surgical research. Anesthesiology 2003;98:609–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agre P, Kurtz R, Krauss B. A randomized trial involving videotape to present consent information for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1994;40:271–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi M, Guttmann D, MacLennan M, et al. Video informed consent improves knee arthroscopy patient comprehension. Arthroscopy 2005;21:739–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants' understanding in informed consent for research. JAMA 2004;202:1593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris D, Rothera M. The application of computer-enhanced imaging to improve preoperative counselling and informed consent in children considering bone anchored auricular prosthesis surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;55:181–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw M, Beebe T, Tomshine P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of interactive, multimedia software for patient colonoscopy education. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001;32:142–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitehouse A, Maybery M, Durkin K. The development of the picture superiority effect. Br J Devel Psychol 2006;24:767–73 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherry K, Park D, Frieske D, et al. Verbal and pictorial elaborations enhance memory in younger and older adults. Aging Neuropsychol Cognition 1996;3:15–29 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drapkin R, Wing R. Responses to hypothetical high risk situations: do they predict weight loss in a behavioral treatment program or the context of dietary lapses. Health Psychol 1995;14:427–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motowidlo S, Dunnette M, Carter G. An alternative selection procedure: the low fidelity simulation. J Appl Psychol 1990;75:640–7 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller C, O'Donnell D, Searight H, et al. The Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test: an assessment tool for clinical research subjects. Pharmacotherapy 1996;16:872–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, et al. Improving the readability and processability of a pediatric informed consent document: effects on parents' understanding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]