Abstract

Soybean is an important crop for Brazilian agribusiness. However, many factors can limit its production, especially root-knot nematode infection. Studies on the mechanisms employed by the resistant soybean genotypes to prevent infection by these nematodes are of great interest for breeders. For these reasons, the aim of this work is to characterize the transcriptome of soybean line PI 595099-Meloidogyne javanica interaction through expression analysis. Two cDNA libraries were obtained using a pool of RNA from PI 595099 uninfected and M. javanica (J2) infected roots, collected at 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after inoculation. Around 800 ESTs (Expressed Sequence Tags) were sequenced and clustered into 195 clusters. In silico subtraction analysis identified eleven differentially expressed genes encoding putative proteins sharing amino acid sequence similarities by using BlastX: metallothionein, SLAH4 (SLAC1 Homologue 4), SLAH1 (SLAC1 Homologue 1), zinc-finger proteins, AN1-type proteins, auxin-repressed proteins, thioredoxin and nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF-2). Other genes were also found exclusively in nematode stressed soybean roots, such as NAC domain-containing proteins, MADS-box proteins, SOC1 (suppressor of overexpression of constans 1) proteins, thioredoxin-like protein 4-Coumarate-CoA ligase and the transcription factor (TF) MYBZ2. Among the genes identified in non-stressed roots only were Ser/Thr protein kinases, wound-induced basic protein, ethylene-responsive family protein, metallothionein-like protein cysteine proteinase inhibitor (cystatin) and Putative Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor. An understanding of the roles of these differentially expressed genes will provide insights into the resistance mechanisms and candidate genes involved in soybean-M. javanica interaction and contribute to more effective control of this pathogen.

Keywords: gene expression, root knot nematode, transcriptome

Introduction

Soybean is the most important agricultural commodity in the world, both in terms of value and quantity. Besides, it is an attractive crop for the production of renewable fuels such as biodiesel. Root-knot nematode (RKN-Meloidogyne spp.) is a serious constraint for many crops, and can significantly affect crop productivity worldwide. In Brazil, this pathogen was responsible for economic losses of over US$52.2 million during the 1999/2000 harvest (Yorinori, 2000).

The use of nematode-resistant cultivars is the most economical and environmentally friendly management strategy for the control of the pathogen (Boerma and Hussey, 1992). The Plant Introduction (PI) 595099, a soybean genotype that is highly resistant to RKN species and to the soybean cyst nematode (SCN) Heterodera glycines (Davis et al., 1998), has been successfully used as a new source of nematode resistance in Brazilian breeding programs (Silva, 2001).

Many physiological changes associated with stress response in plants are controlled at the transcriptional level. Several studies of gene expression have contributed to elucidate the physiological response to infection of soybean roots with Heterodera glycines (Alkharouf et al., 2004, 2005; Khan et al., 2004; Klink et al., 2005; Ithal et al., 2007a,b). Through microarray analysis, it was possible to identify 429 differentially expressed genes during susceptible soybean-H. glycines interaction (Ithal et al., 2007a). These included genes encoding enzymes involved in plant secondary metabolism, such as the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds, lignin, and flavonoids that were up-regulated early during nematode infection and remained overexpressed throughout nematode development. Similarly, genes related to stress and defense responses like pathogenesis-related proteins (PR), cell wall modification enzymes, cellular signaling proteins, and transcriptional regulation factors were consistently up-regulated. Transcript profiling analysis of developing syncytia induced in susceptible soybean by SCN showed interplay among phytohormones that likely regulate synchronized changes in the expression of genes encoding cell wall-modifying proteins. This process appears to be tightly controlled and coordinated with cell wall rigidification processes that may involve lignification of feeding cell walls (Ithal et al., 2007b).

Expressed sequence tags analyzed in other plants inoculated with Meloidogyne spp. identified several genes similar to the ones found in compatible soybean-Heterodera interaction. For instance, in susceptible Arachis spp. inoculated with M. arenaria, arp (auxin-repressed protein) genes were up-regulated whereas cytokynine oxygenase, metallothionein and resveratrol synthase were down-regulated (Proite K, 2007, Doctoral thesis, Universidade de Brasília). The characterization of the transcriptional profile of a compatible tomato response to Javanese nematode demonstrated significant changes in the steady-state transcript levels of several functional categories, including pathogenesis-related genes, hormone-associated genes and development-associated transcription factors (Bar-Or et al., 2005). Responses to M. incognita infection in roots of a resistant cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) genotype and a susceptible near-isogenic line showed that a greater number and proportion of genes were down-regulated in the resistant than in the susceptible genotype, whereas more genes were up-regulated in the susceptible than in the resistant genotype (Das et al., 2010).

In this work we used EST sequence analysis from cDNA libraries of soybean PI 595099 roots at 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after infection (h.a.i.) with M. javanica to assess the gene expression changes during this interaction. This study could lead to new target genes for nematode control and identify candidates for broadening plant resistance to this pathogen through over-expression or gene silencing.

Material and Methods

Nematode inoculum

M. javanica eggs cultured on susceptible tomato host plants were extracted from roots using 0.5% bleach solution (Boneti and Ferraz, 1981) and cleaned with caulim (Coolen and D’Herde, 1972). Eggs were hatched at room temperature and J2 were collected in fresh deionized water.

Root infections for microarray analysis

Soybean PI 595099 seeds were surface sterilized using 10% (v/v) bleach solution, sown in sterilized sand and maintained under controlled environmental conditions at 26.7 ± 2.0 °C temperature and a 16-h photoperiod. After three days, the seedlings were transplanted to seedling growth pouches with sterilized substrate. Eight days after transplant each plantlet was inoculated with 500 J2 M. javanica larvae in 5 mL of deionized water. Five repetitions of inoculated and non-inoculated roots (mock control) were collected at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after inoculation (h.a.i.). Infected and non-infected plants were arranged in a completely randomized design under greenhouse conditions.

RNA isolation

Total RNA from nematode infected and non-infected roots was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) reagent and cleaned with RNeasy Mini Kit for RNA cleanup (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was treated with RNase-Free DNase (Qiagen) to digest any remaining genomic DNA. RNA was quantified using a UV-spectrophotometer and its quality and integrity was examined in 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

cDNA cloning

Two cDNA libraries were constructed comprising the control and the pooled infected root tissues from all intervals. The libraries were prepared using the SMART cDNA Library Construction Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the double-stranded cDNAs were fractioned and cloned in the pTriplEx 2 vector of the same kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The library was amplified in Escherichia coli DH-5 cells (Invitrogen), placed on LB agar and grown overnight at 37 °C. Plasmid preparations of the individual transformants were performed in 96-well plates.

EST sequencing

cDNA inserts were sequenced using specific primers PTR2 (5′CCGCATGCATAAGCTTGCTC3′ - Reverse) and PTF2 (5′GCGCCATTGTGTTGGTACCC3′ - Forward) at Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology, Brazil. Nucleotide sequences and predicted amino acid sequences were analyzed using the SisGen software (Pappas et al., 2008) and Fisher (1932) statistical tests to reveal differential gene expression (Table 1). The criteria applied were a minimum of 30-base similarity between sequences and at least 90% identity. Semiautomatic annotation was performed by BlastX 2.2.3 (Altschul et al., 1990), SwissProt (Bairoch and Apweiler, 1997) and sequences were clustered according to their putative functions by using COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups of Proteins) (Tatusov et al., 2003). The sequences were grouped into contigs. The EST database is housed at the Soybean Genome Project Database (SGPD).

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in soybean (PI 595999) resistant roots uninfected and infected with M. javanica.

| Cluster | 1PIN (115 reads) | 2PII (246 reads) | Statistical tests (p-values) Stekel | Audic-Claverie | Fisher | Blast best hit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig7 | 4 | 2 | 1.52 | 0.037 | 0.089 | Hypothetical protein |

| Contig3 | 1 | 11 | 1.92 | 0.048 | 0.114 | Metallothionein-like protein |

| Contig6 | 0 | 6 | 0.068 | 0.182 | SLAH4 (SLAC1 Homologue 4) | |

| Contig8 | 0 | 5 | 0.1 | 0.33 | SLAH1 (SLAC1 Homologue 1) | |

| Contig9 | 0 | 5 | 0.1 | 0.33 | Zinc finger, AN1-type; A20-type | |

| Contig1 | 1 | 7 | 0.81 | 0.164 | 0.44 | Auxin-repressed protein |

| Contig4 | 4 | 6 | 0.14 | 0.252 | 0.732 | Thioredoxin |

| Contig10 | 2 | 3 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.656 | ACL098Cp |

| Contig16 | 1 | 5 | 0.35 | 0.291 | 0.669 | Auxin-repressed protein |

| Contig2 | 3 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.3 | 0.762 | Nuclear transport factor2 (NTF-2) |

| Contig5 | 3 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.313 | 0.714 | 60S ribosomal protein |

| 11 | 19 | 65 | - | - | - | - |

PIN = PI 595099 uninoculated;

PII = PI 595099 inoculated with M. javanica.

Results

EST validation

Throughout the analysis of the two (RKN-infected and mock control) sequenced cDNA libraries a total of 2,112 sequence reads were obtained and 877 accepted (41%). The valid ESTs were distributed in 195 clusters, these being 79 contigs, and 116 singletons. From these, 55 contigs originated from inoculated (Table 2) and 24 from non-inoculated (Table 3) roots. In silico comparison of the two libraries using the statistical tests of Stekel et al. (2000), Audic and Claverie (1997) and Fisher (1932) (p < 0.005) revealed 11 contigs with significant variation in their transcript levels (Table 1). These transcriptional changes might result from the up-regulation of transcription level or from reduced mRNA expression due to nematode infection.

Table 2.

Expressed genes during soybean (PI 595099) root and M. javanica- interaction.

| Contig | Blast best hit | Organism | Accession code | E-value | Number of ESTs PIN1 | Number of ESTs PII2 | Total number of ESTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig1 | Auxin-repressed protein-like protein, Positives = 48/72 (66%) | Nicotiana tabacum | AY183722.1 | 1e-11 | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Contig2 | Nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF-2), Positives = 113/124 (91%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q9C7F5.1|NTF2_ARATH | 7e-57 | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| Contig3 | Metallothionein-like protein 2 (MT-2) | Cicer arietinum | sp|Q39459.2|MT2_CICAR | 5e-15 | 1 | 11 | 12 |

| Contig4 | Thioredoxin-like 4, Positives = 77/104 (74%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q8LDI5.2|TRXL4_ARATH | 4e-27 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Contig5 | 60S ribosomal protein L23,Positives = 92/93 (98%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG48540.1| | 5e-69 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Contig6 | SLAH4 (SLAC1 HOMOLOGUE 4) Positives = 134/176 (76%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_001077757.1| | 5e-49 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Contig8 | SLAH1 (SLAC1 HOMOLOGUE 1); transporter Positives = 79/113 (69%), | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_176418.2| | 2e-29 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Contig9 | Zinc finger A20 and AN1 domain-containing stress-associated protein 8 (OsSAP8) Positives = 127/169 (75%) | Oryza sativa | sp|A2YEZ6.2|SAP8_ORYSI | 8e-56 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Contig10 | ACL098Cp, Positives = 28/59 (47%) | Ashbya gossypii | ref|NP_983306.1| | 2.7 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Contig11 | N-methyltransferase Positives = 133/160 (83%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_565246.1| | 8e-70 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Contig13 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2-17 kDa 8 Positives = 148/148 (100%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | 834173 UBC8 | 2e-82 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Contig14 | Probable glutathione S-transferase (Heat shock protein 26A) (G2-4), Positives = 56/57 (98%) | Glycine max | gb|AAG34798.1|AF243363_1 | 2e-25 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Contig16 | Auxin-repressed protein Positives = 69/131 (52%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG37064.1| | 5e-13 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| CL1Contig2 | |||||||

| Contig17 | Probableaquaporin PIP-type 7a (Turgor-responsiveprotein 7ª, 31), Positives = 107/108 (99%) | Medicago truncatula | gb|AAK66766.1|AF386739_1 | 1e-54 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Contig18 | Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase ASHR1, Positives = 30/54 (55%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q7XJS0.2|ASHR1_ARATH | 6.1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Contig19 | Auxin response factor 2 (ARF1-binding protein) (ARF1-BP) Positives = 49/57 (85%). | Lycopersiconesculentum | gb|ABC69711.1| | 9e-16 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Contig20 | Adenine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (APRT 1), Positives = 164/174 (94%) | Solanum tuberosum | gb|ABB86271.1| | 2e-81 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Contig21 | Acetyl-CoAcarboxylase, alpha subunit Positives = 31/56 (55%) | Flavobacterium sp. MED217 | ref|ZP_01059904.1| | 34.7 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Contig25 | Chloroplast 50S ribosomalprotein L14, Positives = 94/94 (100%). | Glycine max | ref|YP_538801.1| | 5e-45 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Contig33 | Acyl carrier protein, mitochondrial precursor (ACP) (NADH-ubiquinoneoxidoreductase 9.6 kDasubunit) (MtACP-1), Positives = 79/120 (65%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|P53665.1|ACPM_ARATH | ||||

| 9e-25 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Contig34 | Kinesin light chain 3 (Kinesin light chain KLCt) Positives = 122/137 (89%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | gb|AAM63491.1| | 1e-54 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig35 | Predicted protein Positives = 30/57 (52%) | Pichia guilliermondii | gb|EDK41815.2| | 0.90 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig36 | Putative non-LTR retroelement reverse transcriptase, related Positives = 49/115 (42%) | Medicago truncatula | gb|ABN08132.1| | 1e-06 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig37 | ATP synthase 6 kDa subunit, mitochondrial Positives = 20/23 (86%) | Solanum tuberosum | sp|P80497.1|ATPY_SOLTU | 4e-05 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig38 | Transcription factor MYBZ2 Positives = 131/131 (100%) | Glycine max | gb|ABI73970.1| | 6e-119 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig39 | Thioredoxin-like protein 1 Positives = 149/169 (88%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG24478.1| | 1e-66 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig41 | No hit blast | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Contig42 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide—protein glycosyltransferase subunit DAD1 (Defender against cell death 1) (DAD-1) (AtDAD1), Positives =111/113 (98%), | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_174500.1| | 3e-52 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig43 | Anaphase-promoting complex subunit 11 (APC11) (Cyclosome subunit 11), Positives = 67/83 (80%) | Mus musculus | sp|Q9CPX9.1|APC11_MOUSE | 2e-36 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig44 | Unnamed protein product Positives = 39/54 (72%) | Vitis vinifera | emb|CAO40176.1| | 5e-05 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Contig46 | Inner membrane magnesium transporter mrs2, mitochondrial precursor (RNA-splicing protein mrs2), Positives = 58/120 (48%), | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | sp|P87149.1|MRS2_SCHPO | 8e-05 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig48 | F-box/LRR-repeat protein 16 (F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 16) Positives = 131/144 (90%) | Malus x domestica | gb|ACB87911.1| | 6e-57 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig50 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, cytoplasmicisoform (G6PD) Positives = 89/93 (95%) | Solanum tuberosum | gb|ABB55386.1| | 1e-44 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig51 | Hypothetical protein MtrDRAFT_AC136139g5v2, Positives = 35/38 (92%). | Medicago truncatula | gb|ABE93033.1| | 8e-12 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig52 | USP family protein Positives = 27/30 (90%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG42306.1| | 6e-06 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig53 | Unnamed protein product Positives = 111/119 (93%) | Vitis vinifera | emb|CAO42347.1| | 6e-53 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig54 | 39S ribosomal protein L41-A, mitochondrial precursor Positives = 79/89 (88%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_568574.1| | 8e-35 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig57 | Chalconereductase Positives = 89/106 (83%) | Sesbania rostrata | emb|CAA11226.1| | 3e-33 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig58 | Probable rhamnose biosynthetic enzyme 1 Positives = 94/103 (91%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q9SYM5.1|RHM1_ARATH | 7e-46 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig60 | Ubiquinol—cytochrome-c reductase-like protein Positives = 83/85 (97%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | dbj|BAD95225.1| | 5e-43 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig61 | Translation initiation factor IF-2 Positives = 39/80 (48%) | Plasmodium yoelii | ref|XP_730210.1| | 3.0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig62 | UPF0497 membrane protein At2g28370, Positives = 49/55 (89%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q9SKN3.1|U4977_ARATH | 1e-20 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig63 | MADS-box protein SOC1 (protein suppressor of constans overexpression 1) Positives = 77/82 (93%) | Glycine max | gb|ABC75835.1| | 3e-33 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig64 | SAP domain-containing protein Positives = 84/117 (71%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_201151.2| | 3e-22 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig65 | No blast hit | - | - | - | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig66 | Histone H2A.F/Z Positives = 115/116 (99%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | emb|CAA73155.1| | 4e-54 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig68 | Hypothetical protein MGG_13574 Positives = 28/54 (51%) | Magnaporthe grisea | ref|XP_001408018.1| | 5.9 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig69 | No significant | - | - | - | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig70 | Ferredoxin Positives = 102/118 (86%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG39554.1| | 4e-43 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig71 | HMG1/2-like protein (Protein SB11) Positives = 119/121 (98%) | Glycine max | sp|P26585.1|HMGL_SOYBN | 3e-33 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig72 | ABI5 binding protein A1 Positives = 47/54 (87%) | Triticum aestivum | dbj|BAG12827.1| | 3e-25 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig73 | NAC domain-containing protein 29 (ANAC029) (NAC2) Positives = 64/102 (62%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|O49255.1|NAC29_ARATH | 2e-17 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig74 | At3g08610 Positives = 58/62 (93%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | gb|AAP21180.1| | 4e-23 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig77 | Metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily protein Positives = 48/105 (45%) | Alcanivorax sp. | gb|EDX88588.1| | 1.4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Contig79 | 4-Coumarate—CoAligase-like 5 (Peroxisomal OPC-8:0-CoA ligase 1), Positives = 175/199 (87%). | Oryza sativa | sp|Q10S72.1|4CLL4_ORYSJ | 2e-87 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 55 | - | - | - | - | 19 | 170 | 189 |

PIN = PI 595099 uninoculated;

PII = PI 595099 inoculated with M. javanica.

Table 3.

Expressed genes in uninoculated soybean (PI 595099) roots.

| Contig | Name | Organism | Accession code | E-value | Number of ESTs PIN1 | Number of ESTs PII2 | Total number of ESTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig7 | Hypothetical protein Positives = 66/70 (94%) | Vitis vinífera | emb|CAN65763.1 | 3e-31 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Contig12 | ADP-ribosylation factor Positives = 181/181 (100%) | Hyacinthus orientalis | gb|AAT08648.1| | 2e-99 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Contig15 | Polyprotein Positives = 29/58 (50%) | Potato virus Y | gb|ABC70481.1 | 0.6 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig22 | No hit blast | - | - | - | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig23 | Methionine-R-sulfoxidereductase B1 protein Positives = 130/148 (87%) | Capsicum annuum | gb|ABO64854.1| | 1e-72 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig24 | Ser/Thr protein kinase Positives = 31/31 (100%). | Lotus japonicus | dbj|BAD95894.1| | 7e-10 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Contig26 | Wound-induced basic protein, Positives = 46/47 (97%), | Vitis vinífera | emb|CAO15234.1| | 5e-17 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Contig27 | No hit blast | - | - | - | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig28 | Auxin-repressed 12.5 kDa protein, Positives = 52/55 (94%) | Robinia pseudoacacia | gb|AAG33924.1| | 1e-23 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig29 | 60S ribosomal protein L27a-2 Positives = 124/134 (92%). | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q9LR33.1|R27A2_ARATH | 5e-54 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig30 | No hit blast | - | - | - | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig31 | Putative Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor Positives = 109/109 (100%.) | Glycine max | gb|ACA23205.1| | 2e-59 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig32 | Metallothionein-like protein 1 Positives = 45/57 (78%) | Trifolium repens | sp|P43399.1|MT1_TRIRP | 8e-13 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Contig40 | Cysteine proteinase inhibitor (Cystatin) Positives = 88/94 (93%), | Vigna unguiculata | sp|Q06445.1|CYTI_VIGUN | 5e-41 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig45 | Grx_I1 - glutaredoxin subgroup III, Positives = 94/170 (55%) | Zea mays | gb|ACG27551.1| | 2e-27 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig47 | Ethylene-responsive family protein, Positives = 97/121 (80%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_194639.1| | 7e-42 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig49 | Histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein 1 Positives = 130/154 (84%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | sp|Q9ZNV9.1|AHP1_ARATH | 7e-46 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig55 | Putative mitochondrial ABC transporter ATM1b Positives = 39/79 (49%) | Antonospora locustae | gb|AAY27418.1| | 5.1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig56 | Hypothetical protein Positives = 73/77 (94%) | Vitis vinifera | emb|CAN70604.1| | 5e-32 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig59 | Ribosomal protein L19 Positives = 78/82 (95%) | Hyacinthus orientalis | gb|AAT08672.1| | 5e-26 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig67 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein, putative Positives = 52/53 (98%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | gb|AAM63846.1| | 1e-22 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig75 | Hypothetical protein OsI_20016 Positives = 32/63 (50%) | Oryza sativa | gb|EEC79253.1| | 9.0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig76 | Putative lysine decarboxylase, Positives = 31/32 (96%) | Musa balbisiana | dbj|BAG70979.1| | 5e-08 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Contig78 | Far-red impaired responsive family protein / FAR1 family protein, Positives = 178/235 (75%) | Arabidopsis thaliana | ref|NP_567085.1| | 2e-65 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 24 | 61 | 6 | 67 |

PIN = PI 595099 uninoculated;

PII = PI 595099 inoculated with M. javanica.

Functional classification of ESTs homologous to genes of known function

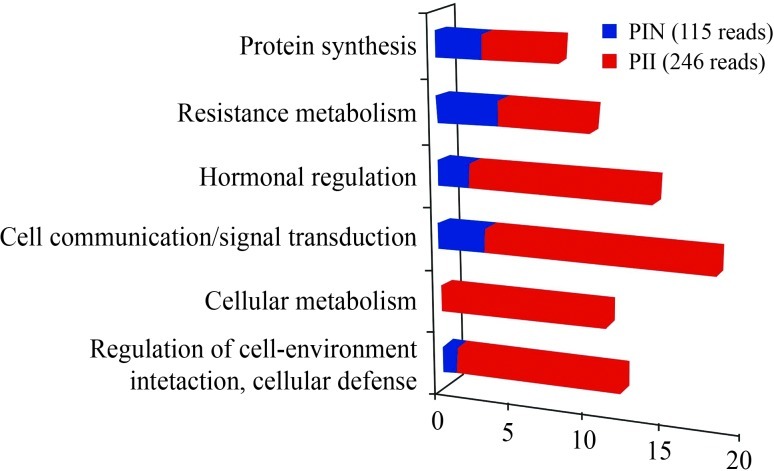

Overall, the most abundant transcripts observed in PI 595099 roots included ESTs encoding genes involved in cell communication/signal transduction [(zinc finger, AN1-type; A20-type); (Nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF-2)], followed by hormonal regulation (Auxin-repressed protein), cellular metabolism [(SLAH4 (SLAC1 Homologue 4); SLAH1 (SLAC1 Homologue 1)], regulation of cell-environment interaction, cellular defense (metallothionein-like proteins), protein synthesis (60S ribosomal proteins) and resistance metabolism (thioredoxin) (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution for differentially expressed genes in soybean (PI 595999) resistant roots uninfected (blue) and infected (red) with M. javanica.

Discussion

In general, the onset of responses governing pest resistance in plants depends on the genotype/species, magnitude and rapidity in which the genes are expressed during the infection. Recently modulated transcript abundance was demonstrated in resistant and susceptible soybean roots during SCN interactions (Mazarei et al., 2011) and also during susceptible soybean- RKN interaction (Ibrahim et al., 2011). The goal of this work was to describe transcriptional changes in PI 595099 resistant soybean line roots during the early stages (6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h) of infection with M. javanica. The in silico functional characterization of the transcribed reads from both libraries revealed a number of genes related either to biotic or abiotic stresses. Here, among the defense responses of PI 595099 towards M. javanica are included up-regulated genes encoding for zinc finger, AN1-type; A20-type; Nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF-2); Auxin-repressed protein; SLAH4 (SLAC1 Homologue 4); SLAH1 (SLAC1 Homologue 1); metallothionein-like proteins, 60S ribosomal proteins and thioredoxin.

Metallothioneins belong to a family of cysteine-rich low molecular weight metal-binding proteins in which the presence of thiol groups promotes its high affinity to heavy metal ions, such as zinc and copper (Inácio AF, 2006, Master’s thesis, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública –FIOCRUZ). Plants expressing metallothioneins better tolerate soils and substrates that are rich in heavy metal ions and are capable of mitigating the damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Chiang et al., 2006), which is associated with hypersensitive response (Wong et al., 2004). In Arachis spp., metallothionein-3 expression was observed only in roots inoculated with M. arenaria race 1 (Proite K, 2007, Doctoral thesis, Universidade de Brasilia). Infected roots of PI 595099 over-expressing the metallothionein gene might use its protein product as a defense mechanism, acting directly in the cell, affecting ROS concentration, in order to avoid damage to the cell wall and even nucleic acids.

SLAC1 (Slow Anion Channel-Associated 1) has been shown to be essential for stomata closure in response to CO2, abscisic acid, ozone, light/dark transitions, humidity, calcium ions, hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide (Negi et al., 2008). The two SLAC1 genes (SLAH4 and SLAH1), expressed only in inoculated root libraries, are possibly involved in ionic regulation, suggested as a defense mechanism of this genotype.

The gene that encodes a 60S ribosomal protein was also significantly regulated in stressed PI 595099 roots. This gene plays an important role in the elongation step of protein synthesis and in this study it might be related to an increase in protein synthesis from genes involved in the defense response to M. javanica. In Poncirus trifoliata its expression was up-regulated when infected by Citrus tristeza virus (Cristofani-Yaly et al., 2007).

There are other transcripts that might be induced in resistant soybean roots during nematode infection, such as the zinc finger protein (Zinc finger, AN1-type, A20-type), which belongs to the gene superfamily SAP (Stress Associated Proteins). Members of this family have been classified according to the number of Cys-His residues that bind the zinc ion (Ciftci-Yilmaz and Mittler, 2008) and are involved in DNA recognition, RNA packaging, transcriptional activation, regulation of apoptosis, protein folding and assembly, and lipid binding (Laity et al., 2001). In cDNA libraries of Poncirus trifoliata infected with Citrus tristeza virus (CTV), zinc finger genes were up-regulated, suggesting the importance of this gene in the plant response to viral infection (Cristofani-Yaly et al., 2007). The exclusive expression of this gene in PI 595099 inoculated roots may indicate the activation of cellular metabolism related to stress in an attempt to control larvae development.

Two arp (Auxin Repressed Protein) genes were differentially expressed in response to nematode infection (Table 1). These genes were previously described in strawberry (Reddy and Poovaiah, 1990), tobacco (Steiner et al., 2003) and pepper (Hwang et al., 2005). They are very similar to genes involved in a dormancy mechanism, with dormancy gene expression being repressed by auxin (Reddy and Poovaiah, 1990; Brinkler et al., 2004; Shimizu et al., 2006). The expression of arp genes is associated with several stresses, such as water stress (Kohler et al., 2003), salt and low temperature (Hwang et al., 2005), fungus (Coram and Pang, 2006), as well as nematode infection (Alkharouf et al., 2004; Proite K, 2007, Doctoral thesis, Universidade de Brasília), among others. Nevertheless, little is known of the importance of arp genes during plant-nematode interaction (de Almeida-Engler et al., 1999). This study provides insights into the arp gene as a possible target of future investigation during plant stress responses, especially in nematode-interactions, since root knot formation is controlled by plant hormones such as auxin (Kim et al., 2007)

In addition to the genes mentioned previously, two Thioredoxin (Trxs) genes were found exclusively in the cDNA libraries from stressed soybean roots. Trxs are small proteins with a redox-active disulfide bridge and are important regulatory elements in plant metabolism (Gelhaye et al., 2005). Two new Trxs isoforms were found specifically in legume with redox potential values similar to those of the classical Trxs, and one of them was shown to act as a substrate for the Medicago truncatula NADP-Trx reductase (Alkhalfioui et al., 2008). In tomato, it was first demonstrated that a CITRX (Cf-9-interacting binding thioredoxin) plays a role in the regulation of plant disease resistance induced through Cf-9 (Rivas et al., 2004). The Trx gene revealed herein as differentially expressed in soybean infected roots may exert negative regulation on plant metabolism and then enhance defense and hypersensitive response (HR).

Gene transcripts with homology to Nuclear Transport Factor 2 (NTF2) were significantly up-regulated in infected soybean roots. A previous study has shown that the overexpression of an NTF2 (IAtNF2a) blocked the nuclear import of a plant transcription factor in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, indicating that the excess of AtNTF2a disrupted nuclear import of a small multifunctional GTPase (Ran) involved in nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, mitotic spindle assembly, and nuclear envelope formation, in a Ran-binding dependent manner (Zhao et al., 2006). The NTF2 gene was up-regulated threefold in PI595099 stressed roots, and this gene is probably contributing to an occasional abnormal cellular disorganization associated with nematode infection observed in these roots (data not shown).

Many compounds involved in plant defense are synthesized in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, such as lignin and phytoalexins. Several stress-induced phenylpropanoids can lead to cell wall polymerization, which is the first physical barrier for pathogen resistance (Dixon and Paiva, 1995). MYB represents the largest transcription factor family in Arabidopsis thaliana (Chen et al., 2005) and is reported to contribute to defense response and regulatory processes in higher plants (Yanhui et al., 2006). The expression patterns herein observed for MYB TFs might be indirectly involved in soybean cell wall resistance, and we infer that they may prevent larvae from penetrating, and therefore would reduce and/or delay gall formation, as observed in PI 595099 roots (data not shown).

An important gene encoding a NAC-domain protein (such as NAM, ATAF1 and CUC2 genes) was detected in the stressed PI 595099 libraries only (Contig73, Table 2). Members of this superfamily of transcription factors possess an N-terminal conserved amino acid sequence named NAC domain and are widely distributed in the plant genomes. The importance of this protein family in a range of biological processes has been reviewed by Olsen et al. (2005). These processes include embryonic, floral and vegetative development, lateral root formation, senescence and auxin signaling, as well as defense and wounding stresses. Members of this family were extensively studied in A. thaliana, which contains more than 90 representatives of NAC domain proteins (AtNAC). It has been also reported that the AtNAC2 gene plays a role in the ethylene and auxin signaling pathways, and is involved in the salt stress response and lateral root development (He et al., 2005).

Another member of this family, the SND1 gene (Secondary wall-associated NAC Domain proteins), is a key regulator compound in the secondary wall of A. thaliana fibers (Zhong et al., 2006). In studies based on the Afimettrix soybean GeneChip, NAC transcription factor probe sets were consistently induced in the resistant TN02 line and suppressed in the susceptible soybean TN02-275 line sister during SCN race 2-interaction (Mazarei et al., 2011). The role of this gene in the resistance response to M. javanica infection in soybean is unknown, but it might be induced by ethylene during injuries caused in the roots by larvae, or in cell-wall strengthening during J2 penetration.

Aquaporin transcripts, such as PIP (plasma membrane intrinsic protein), one of the four groups of plant aquaporins, were also represented in the RKN-infected roots. Aquaporin is a water channel protein that shows increased expression levels in cell membranes and has an important function in cell expansion and division (Okubo-Kurihara et al., 2009). Aquaporin genes have been demonstrated to be associated with H. glycines-inoculated soybean roots (Klink et al., 2005) and rice leaves resistant to Magnaporthe grisea (Jantasuriyarat et al., 2005), indicating that these genes might have relevant roles in plant defense responses. We infer that the presence of aquaporin PIP in PI 595099 stressed roots may elicit the plant defense machinery via water deficit signaling.

Many other genes encoding proteins involved in plant defense were identified in this study, such as the DAD1 (defender against cell death 1) protein, MADS-box protein SOC 1 (suppressor of overexpression constans 1) protein, cytochrome C reductase, SAP (Stress Associated Proteins-domain), glutathione-S-transferase, as well as proteins related to secondary metabolism pathways, such as chalcone synthase and 4-coumarate-CoA. Further studies on these genes will certainly contribute considerably to the understanding of the PI 595099 resistance mechanisms to M. javanica.

It was expected that the gene expression pattern in non-stressed roots would reflect normal root development, and not surprisingly, several ESTs encoding proteins that are involved in plant stress response, including Ser/Thr protein kinase, putative Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor, cysteine proteinase inhibitor, ethylene-responsive family protein and Metallothionein-like protein 1, were represented in the libraries (Table 3). Apparently, the presence of these genes at a low level might indicate an efficient basal resistance, or an injury response due to root development. Provided that these genes have been described to be involved in both injury and insect attack response (Singh et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2009), certain features of the PI 595099 resistance mechanism are probably present in the plant even before pathogen penetration, and the genes discussed in this study (and probably others) are up-regulated so as to to fully express the resistance phenotype.

In conclusion, this study provided a global profile of gene expression changes in soybean PI 595099 during RKN attack, elucidating some elements involved in an incompatible interaction with M. javanica. Validation of the most relevant genes by quantitative PCR should provide a better understanding of RKN parasitism of soybean and aid in the identification of potential targets for genetic improvement of several crops. In addition, histological characterization studies, by monitoring various time points in the penetration and development of M. javanica juveniles (J2) in soybean PI 595099 roots, will provide insights by associating these plant resistance responses with the RKN interaction, and this is the subject of our current studies.

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (Fapemig) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

References

- Alkhalfioui F, Renard M, Frendo P, Keichinger C, Meyer Y, Gelhaye E, Hirasawa M, Knaff DB, Ritzenthaler C, Montrichard F. Novel type of thioredoxin dedicated to symbiosis in legumes. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:424–435. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkharouf N, Khan R, Matthews B. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from roots of resistant soybean infected by the soybean cyst nematode. Genome. 2004;47:380–388. doi: 10.1139/g03-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkharouf NW, Klink VP, Chouikha IB, Beard HS, MacDonald MH, Meyer S, Knap HT, Khan R, Matthews BF. Time course microarray analyses reveal global changes in gene expression of susceptible Glycine max (soybean) roots during infection by Heterodera glycines (soybean cyst nematode) Planta. 2005;224:838–852. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its supplement TREMBL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:31–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Or C, Kapulnik Y, Koltai H. A broad characterization of the transcriptional profile of the compatible tomato response to the plant parasitic root knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2005;111:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma D, Hussey RS. Breeding plants for resistance to nematodes. J Nematol. 1992;24:242–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boneti JIS, Ferraz S. Modificação do método de Hussey e Barker para extração de ovos de Meloidogyne exigua de cafeeiro. Fitopatol Bras. 1981;6:553. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkler M, Van-ZYL L, Liu W, Craig D, Sederoff RR, Clapham DH, von Arnould S. Microarray analysis of gene expression during adventitious root development in Pinus contorta. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Ni Z, Nie X, Qin Y, Dong G, Sun Q. Isolation and characterization of genes encoding Myb transcription factor in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Sci. 2005;169:1146–1154. doi: 10.1080/10425170500272940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HC, Lo JC, Yeh KC. Genes associated with heavy metal tolerance and accumulation in Zn/Cd hyper-accumulator Arabdopsis halleri: A genomic survey with cDNA microarray. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:6792–6798. doi: 10.1021/es061432y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. The zinc finger of network of plants. Cell Mol Life Science. 2008;65:1150–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7473-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coram TE, Pang EC. Expression profiling of chickpea genes differentially regulated during a resistance response to Ascochytarabiei. Plant BioJ. 2006;4647:666. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofani-Yaly M, Berger IJ, Targon MLPN, Takita MA, De Dorta S, Freitas-Astúa J, De Souza AA, Boscoriol-Camargo RL, Reis MS, Machado MA. Differenttial expression of genes identified from Poncirustrifoliata tissue inoculated with CTV analysis and in silico hybridization. Genet Mol Biol. 2007;30(Suppl 3):972–979. [Google Scholar]

- Coolen WA, D’Herde CJ. State Agriculture Research Centre; Ghent: 1972. A Method for the Quantitative Extraction of Nematodes from Plant Tissue Culture; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Ehlers JD, Close TJ, Roberts PA. Transcriptional profiling of root-knot nematode induced feeding sites in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) using a soybean genome array. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:e480. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EL, Meyers DM, Burton JW, Barker KR. Resistance to root-knot, reniform, and soybean cyst nematodes in selected soybean breeding lines. J Nematol. 1998;30:530–541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida-Engler J, Vleesschauwer VDE, Burssens S, Celenza-Junior JL, Inzé D, Montagu MV, Engler G, Gheysen G. Molecular markers and cell cycle inhibtors show the importance of cell cycle progression in nematode-induced galls and syncytia. Plant Cell. 1999;11:793–808. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Paiva NL. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1085–1097. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. 4th edition. Oliver & Boyd; London: 1932. p. 307. [Google Scholar]

- Gelhaye E, Rouhier N, Navrot N, Jacquot JP. The plant thioredoxin system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:24–35. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X-J, Um RL, Cao W-H, Zhang Z-G, Zhang J-S, Chen S-Y. AtNAC2, a transcription factor downstream of ethylene and auxin signaling pathways, is involved in salt stress response and lateral root development. Plant J. 2005;44:903–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang EW, Kim KA, Park SC, Jeong MJ, Byun MO, Kwon HB. Expression profiles of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum) genes under cold stress conditions. J Biosci. 2005;30:101–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02703566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim HMM, Hosseini P, Alkharouf NW, Hussein EHA, El-Din AEKYG, Aly MAM, Matthews BF. Analysis of gene expression in soybean (Glycine max) roots in response to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita using microarrays and KEGG pathways. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:e220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ithal N, Recknor J, Nettleton D, Hearne L, Maier T, Baum TJ, Mitchum MG. Parallel genome-wide expression profiling of host and pathogen during soybean cyst nematode infection of soybean. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007a;20:293–305. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-3-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ithal N, Recknor J, Nettleton D, Maier T, Baum TJ, Mitchum MG. Developmental transcript profiling of cyst nematode feeding cells in soybean roots. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007b;20:510–525. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-5-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantasuriyarat C, Gowda M, Haller K, Hatfiel J, Lu G, Stahlberg E, Zhou B, Li H, Kim H, Yu Y, et al. Large-scale Identification of expressed sequence tags involved in rice and rice blast fungus interactions genome analysis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:105–115. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.055624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan R, Alkharouf N, Beard H, Mcdonald M, Chouikha I, Meyer S, Grefenstette J, Knap H, Matthews B. Micro-array analysis of gene expression in soybean roots susceptible to the soybean cyst nematode two days post invasion. J Nematol. 2004;36:241–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HB, Lee H, Oh CJ, Lee NH, An CS. Expression of EuNOD-ARP1 encoding auxin-repressed protein homolog is upregulated by auxin and localized to the fixation zone in root nodules of Elaeagnus umbellate. Mol Cells. 2007;23:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink VP, Alkharouf N, Macdonald M, Mahews B. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) and expression analyses of Glycine max (soybean) syncytium containing root regions formed by the plant pathogen Heterodera glycines (soybean cyst nematode) Plant Mol Biol. 2005;59:965–979. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler A, Delaruelle C, Martin D, Encelot N, Martin F. The poplar root transcriptome: Analysis of 7000 expressed sequence tags. FEBS Lett. 2003;542:37–41. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. Zinc finger proteins: New insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZB, Janz D, Jiang X, Göbel C, Wildhagen H, Tan Y, Rennenberg H, Feussner I, Polle A. Upgrading root physiology for stress tolerance by ectomycorrhizas: Insights from metabolite and transcriptional profiling into reprogramming for stress anticipation. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1902–1917. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarei M, Liu W, Al-Ahmad H, Arelli PR, Pantalone VR, Stewart CN., Jr Gene expression profiling of resistant and susceptible soybean lines infected with soybean cyst nematode. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:1193–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi J, Matsuda O, Nagasawa T, Oba Y, Takahashi H, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H, Hashimoto M, Iba K. CO2 regulator SLAC1 and its homologues are essential for anion homeostasis in plant cells. Nature. 2008;452:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature06720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo-Kurihara E, Sano T, Higati T, Kutsuna N, Hasezawa S. Acceleration of vacuolar regeneration and cell growth by overexpression of an aquaporin NtTIP1; in tocabacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:151–160. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AN, Ernst HA, Leggio LL, Skriver K. Transcriptional networks in plants NAC transcription factors: Structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas GR, Miranda RP, Martins NF, Fogawa RC, Costa MMC. SisGen; A CORBA based data managenent program for DNA sequencing projects. Lect NotesComp Sci. 2008;5109:116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ASN, Poovaiah BW. Molecular cloning and sequencing of a cDNA for an auxin-repressed mRNA: Correlation between fruit growth and repression of the auxin regulated gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00018554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas S, Rougon-Cardoso A, Smoker M, Schauser L, Yoshioka H, Jones JDG. CITRX thioredoxin interacts with the tomato Cf-9 resistance protein and negatively regulates defence. EMBO J. 2004;23:2156–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Shimizu M, Suzuki K, Miyazawa Y. Differential accumulation of the mRNA of the auxin-repressed gene CsGRP1 and the auxin induced peg formation during gravimorphogenesis of cumcuber seedlings. Planta. 2006;225:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JFV. Sociedade Brasileira de Nematologia e Embrapa Soja; Londrina: 2001. Relações Parasito-Hospedeiro nas Meloidoginoses da Soja; p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Singh IK, Verma PK. Differential transcript accumulation in Cicerarietinum L. in response to a chewing insect Helicoverpa armigera and defence regulators correlate with reduced insect performance. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:2379–2392. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner C, Bauer J, Amrhein N, Bucher M. Two novel genes are differentially expressed during early germination of the male gametophyte of Nicotiana tabacum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1625:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stekel DJ, Git Y, Falciani F. The comparison of gene expression from multiple cDNA libraries. Genome Res. 2000;10:2055–2061. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1325rr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R, Federova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskya AN, et al. The COG database: An updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:e41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HL, Sakamoto T, Kawasaki T, Umemura K, Shimamoto K. Down-regulation of metallothionein, a reactive oxygen scavenger, by the small GTPase OsRac1 in rice. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1447–1456. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanhui C, Xiaoyuan Y, Kun H, Meihua L, Jigang L, Zhaofeng G, Zhiqiang L, Yunfei Z, Xiaoxiao W, Xiaoming Q, et al. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: Expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2910-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorinori JT. Anais do Congresso de Tecnologia e Competitividade da Soja no Mercado Global. Fundação MT; Cuiabá: 2000. Riscos de surgimento de novas doenças na cultura da soja; pp. 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Leung S, Corbett A, Meier I. Identificaton and characterization of the Arabidopsis orthologs of Nuclear Transport Factor 2, the nuclear import factor of Ran1. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:869–878. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.075499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong R, Demura T, Ye ZH. SND1, a NAC domain transcription factor, is a key regulator of secondary wall synthesis in fibers of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3158–3170. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- Soybean Genome Project Database (SGPD, http://bioinfo03.ibi.unicamp.br/soja/ (September 21, 2011).