Abstract

The overall purpose of this study was to provide information on animal and occupational health associated with the infection of a dairy herd with Salmonella Muenster that would be useful in the management of dairy herds so infected. This retrospective, longitudinal report records a 2-year infection of a 140-cow dairy herd with S. Muenster, which was likely introduced by additions to the herd. Six cows aborted or had diarrhea due to salmonellosis in the last trimester of pregnancy. Additions to the herd and the presence of animals that had not received an Escherichia coli bacterin-toxoid were risk factors for salmonellosis. One neonate died, and 24 of 36 calves born between November 1998 and May 1999 had diarrhea by 1 mo of age. Initially, over 60% of the cows were fecal positive; within 6 months, all cows but 1 had become infected. The intermittent shedding of the organism and the eventual zero prevalence highlight the inappropriateness of extensive culling as an eradication strategy. Cultures of the bulk-tank milk filters were more sensitive than cultures of the bulk-tank milk samples at detecting S. Muenster. Two months after the index case, S. Muenster was cultured from the milk of 7.8% of the cows. Positive fecal or milk cultures were not associated with impaired health or production. The herd's milk was a zoonotic risk, but contact with infected animals was not. The organism spread easily between operations, likely via manure-contaminated clothing and footwear.

Introduction

Salmonella spp. are numerous and widespread in the dairy industry. For example, a 1996 United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 1-time fecal sampling of US dairy cows revealed that 5.4% were shedding Salmonella spp. in their feces, and 27.5% of dairy operations had at least 1 animal shedding Salmonella spp. (1). Concern over the isolation of Salmonella spp. stems from the animal health and zoonotic potential of this genus of bacteria. Owing to the zoonotic potential, in some jurisdictions, all Salmonella spp. are reportable, with associated implications for animal movement and liability for spread of the organism.

In the USDA prevalence study, S. Muenster was the 7th most common serotype, accounting for 4.7% of the Salmonella spp. isolates (1). In 1986, the prevalence of Salmonella spp. (primarily S. Muenster) in raw milk samples from dairy herds in southwestern Ontario was 2.9%; the prevalence dropped to zero approximately 1 y later (2,3). Although S. Muenster is not a common cause of salmonellosis in cattle (4), in the early 1980s, an outbreak occurred in southwestern Ontario, with a herd prevalence of 22% (5,6). These reports contain little information that would help in the management of other infected herds, such as the duration and ramifications of infection in individual animals or the herd.

The overall purpose of our longitudinal, retrospective study was to provide information on animal and occupational health associated with the infection of a dairy herd with S. Muenster that would be useful in the management of dairy herds so infected. The specific objectives of this report were: 1) to describe the epidemiology of the infection, including its source, ease of spread between and within operations, prevalence, and zoonotic risk; 2) to describe the clinical and production effects of S. Muenster infection in a dairy herd; and 3) to analyze risk factors associated with infection and salmonellosis.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Data for the report were collected retrospectively in the summer of 2000; they included laboratory culture results and findings in necropsy reports. The herd's extensive records (which included physical examination results, treatments, and a daily herd-management diary) were supplemented with interviews with the herdsman and herd veterinarian, thereby minimizing recall bias. Herd and cow performance data were collected from Western Canadian Dairy Herd Improvement (DHI) Services.

Description of the herd

The herd, averaging 140 Holstein cows, was located on a western Canadian research farm. A multispecies barn that could house beef and dairy cattle, sheep, and swine was located 2 km from the dairy barn.

The cows were housed in an L-shaped tie-stall barn with 55 stalls in 1 wing and 90 stalls in the other. The 55-stall wing had a gravity-fed manure system; the 90-stall wing had a gutter scraper. The cows were exercised in an outdoor pen in groups of 40 to 50 for 1 h, q12h. A total mixed ration was fed. Feeding of animal byproducts (fish meal and tallow) was discontinued in 1997. Milking occurred in a parlor.

Following dry-off, the cows were housed in a dry-cow pen. A few weeks prior to calving, they were returned to the tie-stalls, where they calved. Bull calves were sold a few days following birth. Owing to space constraints, weaned heifers were removed to a custom heifer-rearer's operation. The heifer-rearer also operated a dairy herd, and the heifers of the 2 farms intermingled. Within 1 mo of their expected calving date, the herd's heifers were returned and placed in the dry-cow pen before being placed in a tie-stall to await calving.

The cows were vaccinated with an Escherichia coli bacterin-toxoid (J-VAC; Merial Canada, Baie d'Urfé, Québec) at dry-off and 3 wk prepartum. Every 6 mo, the herd was vaccinated against infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus (IBRV), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), parainfluenza-3 virus (PI3V), and bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) (Triangle 4; Ayerst Veterinary Laboratories, Guelph, Ontario). Sporadically, the herd was vaccinated against clostridial diseases (Covexin 8; Schering Canada, Pointe-Claire, Quebec).

Since 1995, the only animals to enter the herd had been the prepartum heifers returning from the heifer-rearer's operation. Then, on June 4 and 9, 1998, 25 cows of 1st and 2nd parity in late lactation were introduced to the herd in 2 groups. These cows came from more than 6 dairy farms in British Columbia. Prior to entering the herd, all tested negative for Johne's disease and enzootic bovine leukosis. Routine milk culture and somatic cell counts (SCCs) were also done. On arrival, the cows received ceftiofur (Excenel; Pharmacia and Upjohn Animal Health, Orangeville, Ontario), 1 mg/kg BW, IM, and were treated for mange. These animals were housed in a separate pen for 1 wk, and they were milked in the parlor after the other cows. Following the week in the pen, these cows were assigned stalls in the 55-stall wing of the barn and joined the normal herd routine of entering the dry-cow pen until returning to the stall to calve. On June 30, 1998, these new additions received magnets and single doses of the E. coli bacterin-toxoid and the IBRV, BVDV, PI3V, and BRSV vaccine.

Clinical disease

We considered only clinical disease, such as diarrhea or abortion, for which Salmonella spp. were a reasonable potential etiologic agent; salmonellosis was defined as clinical disease with Salmonella spp. confirmed as the etiologic agent. A diagnosis of clinical illness was based on veterinary examination and supporting laboratory testing, including bacteriologic cultures. Aborted fetuses and any available placental membranes were submitted to veterinary pathologists for routine diagnostic examination, including histologic and microbiologic study. Laboratory evaluation of samples from clinical cases was conducted at Veterinary Pathology Laboratory (Alberta Ltd.) (Edmonton, Alberta) and Agri-Food Laboratories Branch (AFLB), Food Safety Division, Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (Edmonton and Lethbridge, Alberta).

Fecal sampling

Two weeks after the 1st confirmed case of salmonellosis (diarrhea on July 7, 1998), fecal samples for the culture of Salmonella spp. were obtained from 26 cows in the 55-stall wing (including 23 of the 25 additions to the herd) whose stalls were near that of the cow with the 1st confirmed case. Subsequently, a fecal culture program for the herd was instituted to monitor the prevalence of S. Muenster infection.

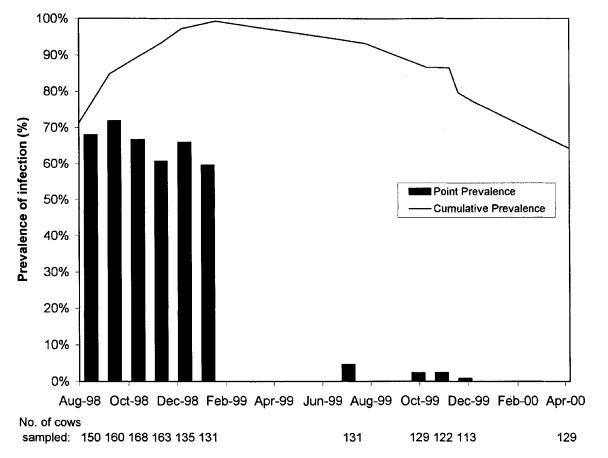

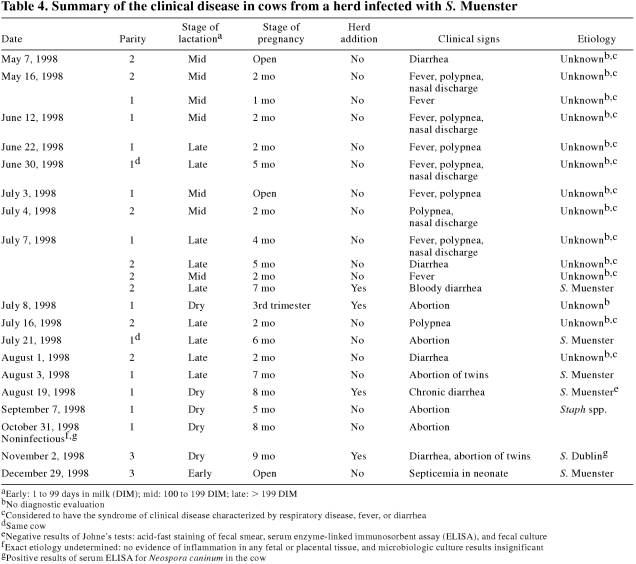

Fecal samples were collected in sterile containers, a separate glove being used for each cow. For a single sampling of the entire herd, fecal sample collection spanned 2 to 3 wk, samples from 50 to 70 animals being cultured each week. This duration of collection was due to constraints on the number of cultures for Salmonella spp. that the laboratory was able to process at a given time. Sampling targeted all of the lactating cows and 25% of the dry cows; the number of cows sampled at each herd sampling is included in Figure 1. Sampling was suspended for 5 mo following the January 1999 sampling, because the point prevalence of infection had remained relatively unchanged. The young stock were included in the August 1998, October 1998, and November 1998 samplings, as well as all those after January 1999.

Figure 1. Apparent point prevalence and cumulative prevalence of Salmonella Muenster in the cow herd. In April 2000, all animals were culture negative.

When it was recognized that the herd was infected, 251 fecal samples were obtained from the lactating cows and a few heifers at the custom heifer-rearer's farm from August 1998 to January 1999. In addition, fecal samples for culture of Salmonella spp. were collected from 22 and 30 beef feeder animals at the multispecies barn on September 23, 1998, and 2 wk later, respectively.

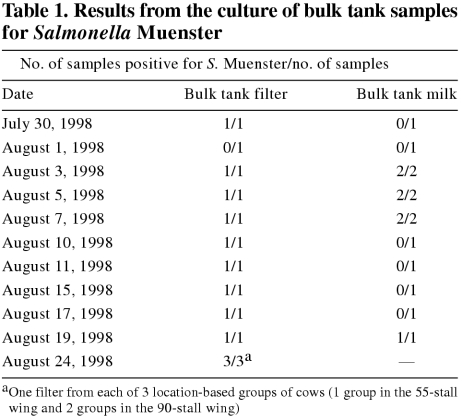

Milk sampling

Table 1 contains the dates on which samples from the bulk tank and the bulk tank milk filter were collected for culture of Salmonella spp. Over 1 wk in September 1998, composite-quarter milk samples from 128 cows were collected by using a standard aseptic technique, which included forestripping and then swabbing the teats with alcohol prior to collection. The cows with positive composite samples were then quarter sampled, and the samples were cultured.

Table 1.

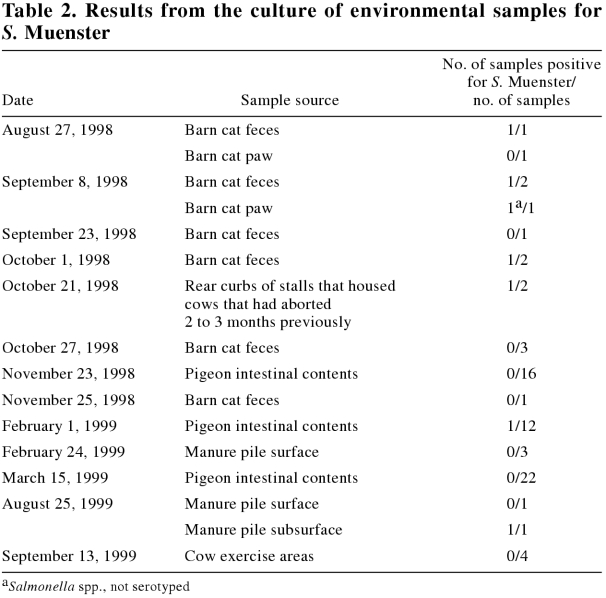

Environmental sampling

Table 2 contains information on the environmental samples collected from the dairy premises for culture of Salmonella spp.

Table 2.

Salmonella spp. cultures

Culturing for Salmonella spp. was conducted by the AFLB. To increase recovery, each sample was inoculated into 2 different recovery pathways. For example, in the case of fecal samples, in the 1st pathway, 5 g of material was inoculated into selenite cystine broth; in the 2nd pathway, 5 g of material was inoculated into buffered peptone water prior to selective enrichment in tetrathionate broth. Following incubation, aliquots from both broths were inoculated onto xylose lysine T4 and Rambach agar plates (7,8). Similar procedures were followed for the culture of tissue, and a previously described standard procedure was followed for the milk samples and the bulk-tank milk filters (9). Presumptive Salmonella spp. colonies were picked and screened by using lysine iron agar and by testing for urease activity. Presumptive positive colonies were confirmed by Salmonella poly O/O1 antisera and by API 20E or GN1 identification systems (Vitek; bioMérieux, St-Laurent, Quebec) when further identification was required. This dual-pathway approach is very sensitive, detecting as few as 3 bacteria per 5 g of fecal material in tests with S. Muenster.

Serotyping and DNA fingerprinting of isolates

All isolates of Salmonella spp. were submitted to the Alberta Provincial Laboratory of Public Health for classical serotyping, with the following exceptions: 1) multiple isolates collected from a single animal, and 2) isolates from the dairy cattles' fecal samples collected prior to February 1999: owing to the high number of isolates, 35 of the 661 were randomly selected for serotyping.

DNA fingerprinting was used to compare 15 of the S. Muenster isolates from animal fecal samples. The origin (and date) of the isolates were as follows: 1 dairy cow (September 1998), 1 beef heifer at the multispecies barn (September 1998), 2 dairy cows and 1 dairy-barn cat (October 1998), 1 dairy-barn pigeon (February 1999), and 6 dairy cows and 3 calves (August 1999). Pulse-field gel electrophoresis DNA fingerprinting (CHEF-DR III; Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) was conducted by the AFLB on the animal isolates, as described by Chang and Chui (10). The restriction pattern was visualized by ethidium bromide staining and analyzed by software (Molecular Analyst Software; Bio-Rad).

Prevalence of infection

An animal was defined as infected if its sample was culture positive for Salmonella spp. The apparent point prevalence and the cumulative prevalence of infection were calculated for each herd sampling. Because the herd was dynamic, cows continually flowing in and out, the calculation of cumulative prevalence (period prevalence) was based on a dynamic population rather than the orthodox approach of defining a static population. This is, the cumulative prevalence indicates the percentage of the cows present in the herd on that date that tested positive on that date or at any time previously. The difference between the cumulative prevalence and the point prevalence on a given date represents the percentage of the herd that tested negative on that date but previously had tested positive.

Statistical analysis

Risk factors for infection at the 1st herd sampling and for salmonellosis were evaluated. The effects of being an addition to the herd and receiving the E. coli bacterin-toxoid on the risk of salmonellosis were evaluated by using risk ratio (RR) analysis (11). The effect of being a herd addition on the risk of salmonellosis was also evaluated by using an incidence density ratio (11). The risk and incidence density ratios measure the direction and strength of association between a risk factor and the outcome of interest. A ratio of less than 1, 1, or more than 1 indicates that the risk factor decreases, has no effect on, or increases the risk of the outcome of interest, respectively. And the closer the ratio is to 1, the weaker the association.

Risk ratio analysis was used to compare risk factors among cows infected at the 1st herd sampling. The 4 risk factors considered were location in the barn (the 55-stall wing or the 90-stall wing), parity (1st or greater), and whether the animals were additions to the herd or in the 2nd half of lactation [more than 199 days in milk (DIM) or dry]. The Mantel-Haenszel technique was used to control for confounding effects. Statistics were analysed by using an analytical software package (Stata Statistical Software, College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was evaluated on the basis of 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If the 95% CI does not include 1, the ratio is statistically significant at the 5% level (P < 0.05).

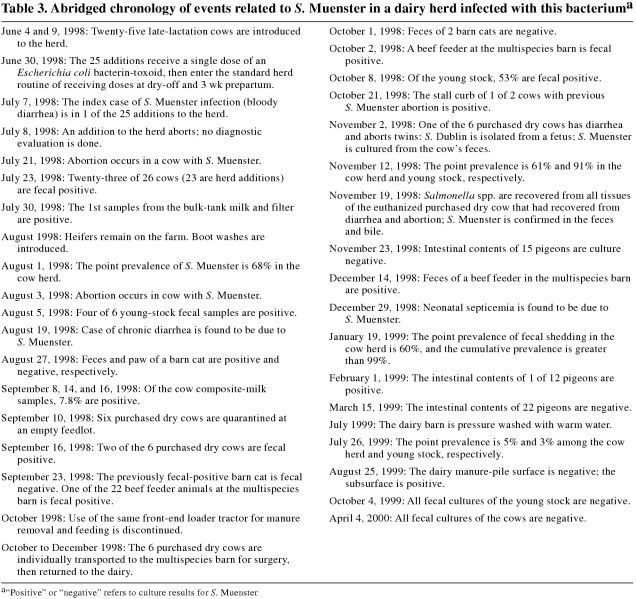

Results

The long timeline of events is further complicated and convoluted by the large volume of data covering many facets of this investigation. Table 3 is a simplified timeline of the important events in the herd infection.

Table 3.

Serotyping and DNA fingerprinting

The 107 Salmonella spp. isolates submitted for serotyping were identified as S. Muenster, except for all 5 isolates from the heifer rearer's operation and the isolate from 1 fetus. The band correlation of the DNA fingerprints of the 15 selected S. Muenster isolates ranged from 85% to 100%, with a maximum of 4 band differences among any of the isolates. Twelve of the 15 isolates (including multiple samples from the dairy herd, a dairy-barn cat, a dairy-barn pigeon, and a beef feeder at the multispecies barn) had identical fingerprints and were genetically indistinguishable (12). The remaining 3 isolates, from August 1999 samples of the dairy animals, differed from the 12 identical isolates by 1 to 3 bands, for a band correlation of at least 85% with the identical isolates. From the number of band differences, we considered these 3 isolates to be closely related genetically, and our epidemiologic interpretation was that they were probably the same strain as the 12 identical isolates (12).

Spread to, and within, other operations

Six dry dairy animals purchased in September 1998 were housed in an empty feedlot some 20 km from the dairy herd to prevent their infection with S. Muenster. A week after arriving, 2 of the 6 cows, in different pens, tested positive for S. Muenster by fecal culture. During this week, 3 persons from the research farm had contact with the animals. Only 1 of the 3 maintained separate clothing and footwear for each location, and at least 1 of the 3 traveled from the dairy barn to the feedlot. In October 1998, following their exposure to the organism, the 6 cows were added to the dairy herd and were housed in the 55-stall wing of the barn.

Salmonella Muenster was isolated from the same beef feeder at the multispecies barn on September 23, 1998 (n = 22) and again 2 wk later (n = 30). Thereafter, boot washing and fecal sampling of all new additions to the barn were implemented. The feeders were housed in individual pens, but they were exercised daily as a group in a small pasture.

From October to December 1998, the 6 purchased dry cows were transported individually, by tractor and trailer, to the multispecies barn and returned to the dairy on the same or the following day. These 6 animals were the only animals to move from the dairy to the multispecies barn in 1998. While at the multispecies barn, the cows were isolated, access to personnel was limited, and the area containing the cows was disinfected immediately following the animals' removal. In December 1998, S. Muenster was isolated from a single beef feeder in a group of 5 at the multispecies barn. The feces of all 5 had cultured negative on both previous sampling occasions. The only equipment to travel directly between the dairy and the adjacent barn was the tractor and trailer used to transport the 6 cows. Salmonella Muenster was not isolated from animals at the custom heifer-rearer's premises.

Clinical disease

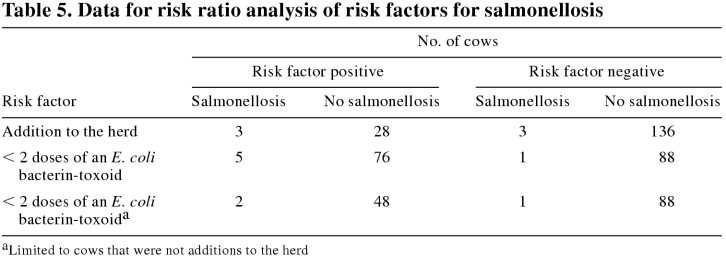

Table 4 summarizes the relevant clinical disease in the cow herd, ending with the last diagnosed case of salmonellosis.

Table 4.

From May to August, an estimated 10% of the herd was examined for a syndrome of clinical disease with 3 presentations, all of undiagnosed etiology. The most common presentation was respiratory disease, characterized by fever, inappetence, clear nasal discharge, and polypnea with increased normal breath sounds. Occasionally, cows were either febrile or had watery diarrhea but minimal systemic signs. Salmonellosis was not a differential diagnosis in any of these cases. All the cows recovered fully. Most were treated with ceftiofur, 1 mg/kg BW, IM, for 1 to 5 d.

All of the herd additions, including those with clinical illness, were housed in the 55-stall wing. All of the other cows with clinical disease were housed in the 90-stall wing. Of the confirmed cases of salmonellosis, the 1st case had received a single dose of E. coli bacterin-toxoid and the last case had received a minimum of 2 doses; the other 4 cases had received no doses.

The cow with the 1st confirmed case was febrile and depressed and had bloody diarrhea. It was treated with trimethoprim-sulfadoxine (Trimidox; Rhône Mérieux, Victoriaville, Quebec), 16 mg/kg BW, IM, q24h for 3 d. The culture of S. Muenster from the fecal sample confirmed the differential diagnosis of salmonellosis.

The November 2, 1998, case was in 1 of the 6 purchased dry cows. Salmonellosis occurred 3 wk after major gastrointestinal surgery and was treated with trimethoprim-sulfadoxine (16 mg/kg BW, IM, q24h for 5 d) and procaine penicillin G (Penicillin G Procaine; P.V.U., Lavaltrie, Quebec), 300 000 IU/kg BW, IM, q24h for 5 d. Salmonella Dublin was isolated from the stomach contents of 1 of the aborted fetuses, but it was ruled as the likely cause of the abortion only because gross and histologic examination had failed to reveal any evidence of significant bacterial infection in the fetal or placental tissues. Culture of a fecal sample from the cow 2 d after the abortion revealed S. Muenster. Although the cow had recovered from the salmonellosis, she was euthanized and necropsied 12 d after the completion of her treatment, when the herd management was notified that S. Dublin had been identified in 1 fetus. Salmonella spp. were isolated from all tissues (feces, mesenteric lymph node, liver, gallbladder, bile, spleen, and uterus) submitted for culture. The isolates from the feces and bile were serotyped as S. Muenster. The histologic findings in the liver, spleen, and uterus, but not the intestine, were consistent with Salmonella spp. infection.

Only incomplete records were available to characterize clinical disease among the young stock. In the summer and fall of 1998, a change in general health was not noted among the young stock, which, owing to seasonal calving, were relatively few. Of the 36 heifer calves born between November 1998 and May 1999, 24 had diarrhea within 1 mo of birth. The vast majority of the dams of these 36 calves had been infected with S. Muenster prior to the calves' births and had received 2 doses of E. coli bacterin-toxoid in the immediately preceding dry period and possibly in earlier dry periods as well. The tentative diagnosis of salmonellosis was supported by negative results from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for rotavirus and coronavirus in fecal samples from 3 calves. The calves responded to treatment with antibiotics and oral fluids.

Prevalence in feces

Of the 26 cows in the 55-stall wing that had initial fecal sampling for culture, 23 (88.5%) were culture positive for S. Muenster. Figure 1 presents the results of the fecal culture program to monitor the prevalence of S. Muenster infection in the herd. The bars represent the apparent point prevalence of S. Muenster infection at each herd sampling. For the first 6 mo, samples from 60% to 72% of the cows cultured positive in each herd test. When herd culturing resumed 6 mo later, roughly 1 y after the initial discovery of S. Muenster in the herd, the apparent prevalence was less than 5%. Over the following 10 mo, the apparent prevalence continued to decrease, until April 2000, when none of the 129 cows' samples cultured positive for any Salmonella spp. The young stock experienced a similar, but shorter, pattern of apparent point prevalence: they were infected as of August 1998, but the point prevalence was zero as of October 1999.

The line above the bars in Figure 1 represents the cumulative prevalence of Salmonella spp. infection in the cow herd over time. The cumulative prevalence continued to rise until January 1999, when 137 of 138 cows either were currently or had previously been infected with S. Muenster. Thereafter, no new infections occurred among the dairy cows (no cows were infected for the 1st time), and the percentage of the herd that had tested positive at least once continued to decline. In April 2000, when none of the cows' cultures were positive, 64% of the herd had previously had positive cultures for S. Muenster. The decrease in the cumulative prevalence resulted from replacement of the 37% of cows culled annually. The young stock population experienced a pattern of cumulative prevalence similar to that of the cows.

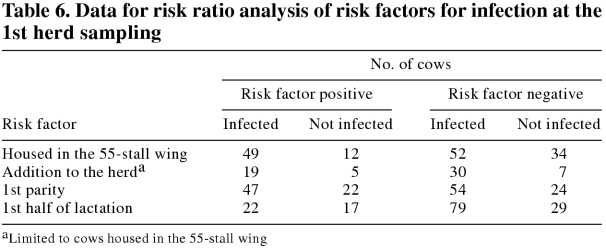

Risk factors for salmonellosis and for infection at the 1st herd sampling

The additions to the herd consisted of the 25 cows purchased in June 1998 and the cows purchased in September 1998. The additions to the herd, none of which had received 2 doses of the E. coli bacterin-toxoid, had over a 4-fold increase in the relative risk of salmonellosis (Table 5; RR = 4.5; 95% CI = 0.95 to 21.2). Salmonellosis occurred only in the 2nd half of lactation, and all the additions to the herd were in late lactation or dry. Thus, the potential for overestimating the risk of the effect of being an addition to the herd existed, although it would be somewhat countered by the herd's high average number of DIM. The risk of a herd-addition effect was, therefore, also evaluated by comparing the incidence density ratio of salmonellosis per number of DIM greater than 200 in the last 6 mo of 1998 (when the clinical cases occurred). From the incidence rates (the number of DIM greater than 200 was 1823 for the additions to the herd and 16 457 for cows that were not additions to the herd), the estimated increase in the risk of salmonellosis for the additions to the herd was greater and statistically significant (incidence rate ratio = 9.0; 95% CI = 1.2 to 67.4).

Table 5.

Cows that did not receive a minimum of 2 doses of the E. coli bacterin-toxoid faced 5 times the risk of salmonellosis (Table 5; RR = 5.5; 95% CI = 0.7 to 46.0) relative to the vaccinates. Perfect confounding existed between the additions to the herd and vaccination with an E. coli bacterin-toxoid, as none of the additions to the herd received 2 doses of this agent. To evaluate the effect of vaccination on the risk of salmonellosis independent of the effect of being a herd addition, we calculated the RR using only cows that were not herd additions. Among these cows, failure to vaccinate resulted in a nearly 4-fold increase in risk (Table 5; RR = 3.6; 95% CI = 0.3 to 38.3). Correcting for stage of lactation had little impact on the effect of vaccination on the risk of salmonellosis.

Being housed in the 55-stall wing of the barn had little effect on the risk of fecal samples being positive on culture at the 1st herd sampling (Table 6; RR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.08 to 1.64). Within the 55-stall wing, the risk of infection for the additions to the herd and the cows native to the herd was not different (Table 6; RR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.79 to 1.33). A 1st-lactation animal was not at greater risk of a positive fecal culture than older animals (Table 6; RR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.79 to 1.22). The 39 animals in the 2nd half of lactation had a slightly greater risk of a positive fecal culture (Table 6; RR = 1.30; 95% CI = 0.96 to 1.75). Controlling for confounding factors did not affect the risk of infection at the 1st herd sampling.

Table 6.

Fecal shedding patterns

The pattern of results from fecal culture varied among the cows. Of the 187 cows that had more than 2 fecal samples cultured, 35% (66) had at least 1 negative culture interspersed among positive cultures. Conversely, 65 cows had 4 to 8 consecutive positive fecal cultures, beginning with their 1st culture; 55 subsequently had negative cultures, and the remaining 10 (including the 2 whose 8 fecal samples were all culture positive) were culled. The pattern of fecal culture results of the young stock was similar to that of the cows but less remarkable. For example, it was rare for the young stock to have positive cultures for more than 4 mo, and it was rare for those that had positive cultures to have a negative culture interspersed among the positive cultures. Relative to the cows, the lower frequency of sampling in the young stock contributed to these tempered results. Three of the 5 animals with salmonellosis from which fecal samples were cultured 5 d, 3 wk, and 3 mo prior to the development of clinical signs, respectively, were shedding the organism in their feces. All 5 animals with salmonellosis from which fecal samples were cultured subsequent to clinical recovery shed S. Muenster for 1 to 12 mo.

Prevalence in milk

Table 1 presents the results from the culture of bulk-tank samples for S. Muenster.

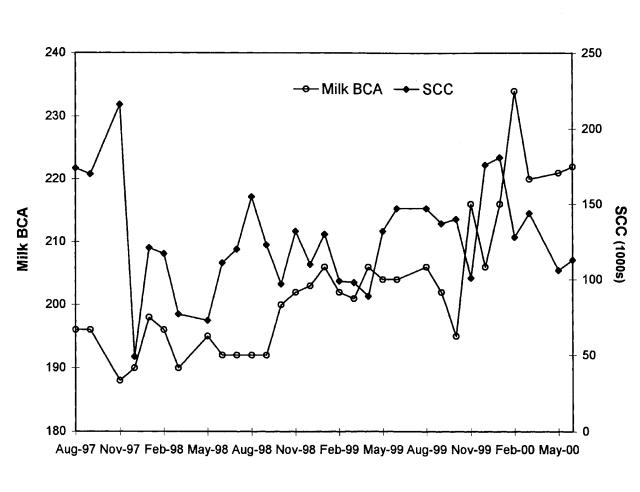

Ten (7.8%) of the composite-quarter milk samples collected from 128 cows in September 1998 yielded S. Muenster. All 10 cows had had culture-positive fecal samples collected in the 2 wk preceding collection of the quarter milk samples. Six of the 10 were from the group of 25 new additions to the herd. Isolation of the bacterium from a cow's milk was not associated with an elevated SCC. Quarter milk sampling of 9 of the 10 cows 2 wk later revealed that 3 cows had 1 or 2 quarters that were positive for S. Muenster. A week later, the same quarters were negative for Salmonella spp. During the period when the organism was being isolated from the milk, the herd management did not note any increase in the incidence of clinical mastitis. Figure 2 does not reveal abnormal increases in the herd SCC.

Figure 2. Milk production and udder health in the herd. BCA — breed class average; SCC — somatic cell count.

Herd production

Aside from the clinical cases observed at the beginning of the herd infection, the herd management did not notice any adverse effects of the largely subclinical infection on herd performance, including milk production, udder health, and general health. Figure 2 supports this impression: the milk breed class averages (BCAs) maintained an upward trend, and the SCCs showed no trend, over the course of the infection.

Environmental distribution

Table 2 presents the results of culturing the environmental samples from the dairy premises for Salmonella spp.

Management changes

The commercial laboratory that identified Salmonella spp. in the fecal culture in the 1st confirmed case duly notified the provincial Department of Agriculture, because salmonellosis is a reportable disease. Under provincial legislation, livestock with a listed communicable disease cannot be sold for breeding purposes without notification of the proposed purchaser.

As of August 1998, upon recognition of the high level of infection in the herd, heifers were kept at the dairy facility rather than being sent to the custom heifer-rearer. All marketable animals leaving the dairy were sold directly to a slaughter facility, with full disclosure of their shedding status. In addition, clothing worn at the dairy facility was to be left there. The use of boot washes was instituted, and footwear worn in the barn was no longer worn into the laboratories or other nonbarn areas of the dairy facility. Bleach was applied to the rear of the stalls for 1 wk following calving. In October 1998, use of the same front-end loader tractor for manure removal and feeding was discontinued. In September 1999, both wings of the barn were pressure washed with warm water.

Occupational health

Following the isolation of S. Muenster from the milk, those in contact with the milk (the milk hauler and the DHI technicians), as well as the dairy employees, were made aware of the bacterium's zoonotic potential. None of the staff reported clinical signs consistent with infection, and all declined to have their feces cultured. Visitors to the dairy wore disposable footwear and coveralls and were instructed to wash their hands upon leaving the unit.

Discussion

Salmonella spp. serotyping

From the serotyping results, we extrapolated that all of the unserotyped Salmonella spp. isolates associated with the dairy operation and multispecies barn were S. Muenster. The fetal isolate of S. Dublin from the case of diarrhea and abortion of twins is suspect: S. Dublin is characteristically endemic, with sporadic cases occurring (4), yet this was the sole isolation of S. Dublin in an intensive Salmonella spp. monitoring program. In addition, S. Muenster, not S. Dublin, was isolated from the feces, liver, and bile of the cow. While instances of multiple serovars from a single dairy have been reported, this situation is not considered common (13).

Spread to, and within, other operations

The organism spread from operation to operation, likely via manure-contaminated clothing and footwear, as previously documented (4), although the degree of spread within farms varied greatly. Humans were the only apparent vector for the spread of S. Muenster to the 6 cows isolated 20 km from the dairy herd or to the animals housed in the multispecies barn on the research farm. Rapid spread of the disease to neighboring herds was noted in the outbreak in Ontario, although the means of spread was not determined (5).

The lack of spread of the organism within the multispecies barn or to the heifer-rearer's operation is interesting. The dairy young-stock population was infected with S. Muenster before the shipment of heifers to the heifer-rearer was discontinued, so it is likely that some infected animals were included in the shipments. The use of individual pens at the multispecies barn and the smaller amount of manure produced by the infected beef animals and dairy heifers likely contributed to reducing the spread. The lack of spread on these 2 operations contrasts sharply with the ease of spread on the dairy farm and in the outbreak in Ontario (5).

Source of the S. Muenster

The DNA fingerprinting results for the S. Muenster isolates, which varied in geographic and species distribution, strongly suggested that all of the animal isolates were identical. This was consistent with a point source of S. Muenster. The limited number and short duration of S. Muenster isolations from other species, coupled with the extensive infection of the cattle, suggested that the source of infection was associated with cattle.

We considered 4 potential cattle-associated sources of the S. Muenster. Failure to isolate S. Muenster from animals at the heifer rearer's farm suggested that this farm was not the source. Because the organism spread to other operations, a fomite that had been contaminated with S. Muenster-infected manure was a potential source. However, for the organism to remain viable, the source farm, which would likely have experienced salmonellosis, would need to have been close to the research herd, and the provincial veterinarian was not notified of any other cases of salmonellosis due to S. Muenster prior to or during the infection of the herd. Most likely, the organism was introduced to the herd via the group of 25 additions, although the government laboratory in the province from which these cattle originated had never isolated S. Muenster from mammals (Dr. Henry Lange, Animal Health Centre, British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture and Food: personal communication). Alternatively, the organism may have already been present in the herd, and the introduction of the 25 immunologically naïve and stressed animals presented an opportunity for propagation and spread of the organism. This explanation is less plausible, because it is difficult to reconcile why, if the organism was already in the herd, salmonellosis had not already occurred. Susceptibility to infection and salmonellosis was not limited to the new additions to the herd; moreover, animals with diminished immunologic competence — heifers returning from the custom heifer rearer's operation — were continually entering the herd.

Clinical disease

It is possible, but unlikely for a number of reasons, that the syndrome of respiratory disease, fever, and diarrhea experienced by 10% of the herd between May and August 1998 was salmonellosis. First, respiratory disease and fevers are atypical presentations for salmonellosis, although there could have been another disease agent in conjunction with S. Muenster. Second, the animals with confirmed salmonellosis were systemically ill, whereas the animals affected by the syndrome had minimal, if any, systemic involvement. This differing severity of disease was reflected in the herd veterinarian's inclusion of salmonellosis as a differential diagnosis for the cases of salmonellosis but not for the disease syndrome. Third, if the syndrome was due to S. Muenster, the herd must have been infected prior to the arrival of the 25 new additions, and, as discussed, this is unlikely.

During the first 6 mo of the 2 y that the herd of 140 cows was subclinically infected with S. Muenster, there were 6 confirmed diagnoses of salmonellosis. The affected cows were typically in their 1st lactation, an addition to the herd, or recovering from major surgery. This suggests that factors such as stress may have tipped the agent-host balance in favor of S. Muenster, resulting in salmonellosis. The finding that some of the cows were fecal positive prior to their succumbing to clinical disease supports this suggestion.

Cases of salmonellosis typically involved diarrhea or abortion in the last trimester of pregnancy, whereas it has been reported that abortions due to S. Muenster occur at any stage of gestation (14). The clinical disease in this herd is consistent with the variable morbidity, relatively low mortality, and occasional abortion reported among herds involved in the outbreak in Ontario (6). In contrast, Styliadis and Barnum (5) reported that abortion is common in infections with S. Muenster. Disease among the young stock occurred for 1 y following identification of the 1st confirmed case. The 66% morbidity among a portion of the young stock, and only a single neonatal death, is inconsistent with the outbreak in Ontario, in which very few calves were affected (6), and with Sanford's report that the rate of death due to S. Muenster may be high in calves but is low in adults (14). The high morbidity of these calves within the 1st month of life suggests that the colostrum from dams that were either infected with the organism or vaccinated with an E. coli bacterin-toxoid did not confer immunity.

Cows that were additions to the herd or were not vaccinated with an E. coli bacterin-toxoid had more than a 3-fold increase in the risk of salmonellosis. Administration of primary and booster doses of an E. coli bacterin-toxoid might have protected against salmonellosis due to S. Muenster. Although the vaccine is labeled for protection against S. Typhimurium endotoxemia, protection against S. Muenster is not unexpected, because E. coli J5 vaccine targets antigens common to diverse species of gram-negative bacteria (15). However, receipt of a single dose had little protective effect, as evidenced by the clinical disease in the group of 25 additions to the herd.

Prevalence in feces

A number of inferences can be drawn from the patterns of point and cumulative S. Muenster prevalence in the cow herd, as represented by Figure 1 (the patterns for the young stock were similar). The initial rising cumulative prevalence is consistent with the spread of the organism by ingestion of material contaminated with the feces of infected cows. Propagative spread is typical of Salmonella spp. (4). Rapid spread of the organism within a herd was also noted in the outbreak in Ontario (5). The climaxing of the cumulative prevalence of infection at almost 100% and the failure to identify cow-level risk factors for infection when the herd was first cultured indicate that all animals in the herd were susceptible to infection. In general, a tie-stall-housed herd would be expected to have less infection pressure than a free-stall herd owing to decreased exposure to manure. However, milking the cows in a parlor rather than using a pipeline and using the same equipment for feeding and manure handling likely contributed to the high level of transmission. The latter practice was stopped 3 mo prior to the peaking of cumulative prevalence.

The dramatic decrease in point prevalence and the cessation of new infections following the climax in cumulative prevalence suggest that herd immunity to S. Muenster may have played a role in clearing the organism from the herd. Herd or population immunity has been suggested as a reason for the disappearance of S. Muenster from the bovine population in southwestern Ontario in the 1980s (3). The concept of herd immunity, coupled with the infection of nearly all the animals, raises the issue of whether actively promoting infection of the animals would have reduced the duration of herd infection. While the persistence of the organism in the herd was presumably longer than that alluded to in the outbreak in Ontario (5), this length of persistence without clinical signs has been reported with other Salmonella serovars (13). Infection of animals occurred despite their receiving the bacterin-toxoid. Any systemic immunity conferred by vaccination would not be expected to provide localized immunity at the level of the gut, as evidenced by the continued fecal shedding of S. Muenster by the animals that recovered from salmonellosis.

Fecal shedding patterns

The interspersing of negative fecal cultures among positive results is consistent with the intermittent shedding commonly associated with Salmonella spp. This report appears to be one of the few to document intermittent shedding of a nonhost-adapted serovar. The literature suggests that following infection with serotypes other than S. Dublin, excretion is usually limited to a few weeks or months and further excretion probably reflects recontamination from the environment (16). The imperfect sensitivity of microbiologic culture as a test for infection likely contributed to the intermittent results. It is reasonable to expect that the selective culture technique has very high specificity, but false-negative results (less than perfect sensitivity) likely occurred, despite the dual-pathway enrichment. In retrospect, situations such as this with a high prevalence for an extended duration present excellent opportunities to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the sampling strategy (17, 18). The interspersing of negative fecal culture results among positive results and the eventual zero apparent point prevalence highlight the inappropriateness of extensive culling as a strategy to eradicate S. Muenster from the herd.

Relative to the cows, the shorter period of shedding among the young stock, individually and as a population, is inconsistent with the findings in the Ontario outbreak, in which ". . . calves continued to carry the organism for a number of months whereas the cows did not remain carriers for the same length of time . . ." (5).

Prevalence in milk

The bulk tank milk and filter samples clearly indicated the presence of S. Muenster in the milk and the human-health risks associated with consumption of nonpasteurized milk (4). In addition, feeding of milk infected with S. Muenster to young stock is a potential means of spread. The findings of this study are consistent with the conclusion that the only significant change in herd milk production or milk composition associated with S. Muenster isolation from bulk tank milk filters was higher plate-loop counts (19). The finding that cultures derived from filters appear to be more sensitive than those from milk samples from the bulk tank in detecting S. Muenster is in agreement with research on the outbreak in Ontario (5).

In contrast with the current study, Styliadis and Barnum (5) reported that S. Muenster can be shed in the milk from cows with negative fecal samples. The bacterium was isolated from the milk of affected cows for a maximum of a few weeks and was associated with, at worst, mild subclinical mastitis. Experimental studies have revealed that the organism can colonize the mammary gland, resulting in a moderate increase in the SCC (5). Failure to isolate other bacteria from the milk samples should not be overinterpreted as ruling out contamination of the milk, because the culture technique employed was selective for Salmonella spp. Combined, the bulk-tank and individual-cow milk cultures revealed that the herd milk was positive for S. Muenster for at least 2 mo. This duration of shedding in the milk has been reported previously (2).

Environmental distribution

The cow manure was a source of S. Muenster. In the moist environment of the barn and within the manure pile, the organism remained viable for extended periods. The cats, which were positive for a much shorter period than the cows, were likely infected by contact with the cow manure (the cats were not fed raw milk). Surprisingly, only 1 of 50 pigeons was culture positive: pigeons are commonly considered a reservoir for Salmonella spp.

Management changes

The use of common machinery for manure removal and feeding likely contributed to spread of the organism. Maintaining all young stock on the farm to prevent infection of the heifer-rearer's herd also likely contributed to the spread of the infection, because of crowding. The management changes undertaken were not extensive and, as a result, the course of infection in the herd can be considered to have been relatively uninhibited.

Occupational health

The lack of diagnosis of salmonellosis among the farm workers and visitors, despite their exposure to contaminated body fluids of the cattle, suggests that humans are not highly susceptible to clinical disease due to S. Muenster. In the outbreak in Ontario, the human cases were commonly associated with consumption of raw milk and rarely associated with animal contact (5).

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The Alberta Provincial Laboratory of Public Health is gratefully acknowledged for serotyping isolates. The assistance of the Agri-Food Laboratories Branch personnel and Harold Lehman in data collection and generation was greatly appreciated. CVJ

Funding for culturing was provided by the Animal Industry and Food Safety divisions of Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, Alberta Milk Producers, and the Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutritional Sciences, University of Alberta.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Brian R. Radke.

References

- 1.Wells S, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Besser T, McDonough P, Smith B. E. coli O157 and Salmonella — status on U.S. dairy operations. National Animal Health Monitoring System Dairy '96 Study. http://www.aphis.usda.gov:80/vs/ceah/cahm/Dairy_Cattle/ecosalm98.htm

- 2.McEwen SA, Martin SW, Clarke RC, Tamblyn SE, McDermott JJ. The prevalence, incidence, geographical distribution, antimicrobial sensitivity patterns and plasmid profiles of milk filter Salmonella isolates from Ontario dairy farms. Can J Vet Res 1988;52:18-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.McEwen SA, Martin SW, Clarke RC, Tamblyn SE. A prevalence survey of Salmonella in raw milk in Ontario, 1986-87. J Food Prot 1988;51:963-965, 970. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Radostits OM, Blood DC, Gay CC. Veterinary Medicine. 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall, 1994:730-746.

- 5.Styliadis S, Barnum D. Salmonella muenster infection in man and animals in the province of Ontario. Proc Int Symp Salmonella, New Orleans, 1984:200-208.

- 6.Barnum DA. Salmonella muenster: a new problem in Ontario dairy herds. Highlights of Agricultural Research in Ontario. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food, 1983;6:4-7.

- 7.Mallinson ET, Miller R, de Rezende C, Ferris K, deGraft-Hanson J, Joseph S. Improved plating media for the detection of Salmonella species with typical and atypical hydrogen sulfide production. J Vet Diagn Invest 2000;12:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dusch H, Altwegg M. Evaluation of five new plating media for isolation of Salmonella species. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:802-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.D'Aoust JY, Purvis U. Isolation and identification of Salmonella from foods. In: Warburton D, ed. Compendium of Analytical Methods. Vol 2. Laval: Polyscience Publ, 1998:1-19.

- 10.Chang N, Chui L. A standardized protocol for the rapid preparation of bacterial DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1998;31:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic Research. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1982:141-143.

- 12.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulse-field electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Gay JM, Hunsaker ME. Isolation of multiple Salmonella serovars from a dairy two years after a clinical salmonellosis outbreak. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;203:1314-1320. [PubMed]

- 14.Sanford SE. Some respiratory and enteric diseases of cattle: an update. Mod Vet Pract 1984;65:265-268. [PubMed]

- 15.Mutharia LM, Crockford G, Bogard WC, Hancock REW. Monoclonal antibodies specific for Escherichia coli J5 lipopolysaccharide: cross-reaction with other gram-negative bacterial species. Infect Immun 1984;45:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wray C, Sojka WJ. Reviews of the progress of dairy science: bovine salmonellosis. J Dairy Res 1977;44:383-425. [PubMed]

- 17.Buelow KE, Thomas CB, Goodger WJ, Nordlund KV, Collins MT. Effect of milk sample collection strategy on the sensitivity and specificity of bacteriological culture and somatic cell count for detection of Staphylococcus aureus intramammary infection in dairy cattle. Prev Vet Med 1996;26:1-8.

- 18.Funk JA, Davies PR, Nichols MA. The effect of fecal sample weight on detection of Salmonella enterica in swine feces. J Vet Diagn Invest 2000;12:412-418. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.McClure LH, McEwen SA, Martin SW. The associations between milk production, milk composition and Salmonella in the bulk milk supplies of dairy farms in Ontario. Can J Vet Res 1989;53:188-194. [PMC free article] [PubMed]