Abstract

Objective

To describe core principles and processes in the implementation of a navigated care program to improve specialty care access for the uninsured.

Study Setting

Academic researchers, safety-net providers, and specialty physicians, partnered with hospitals and advocates for the underserved to establish Project Access-New Haven (PA-NH). PA-NH expands access to specialty care for the uninsured and coordinates care through patient navigation.

Study Design

Case study to describe elements of implementation that may be relevant for other communities seeking to improve access for vulnerable populations.

Principal Findings

Implementation relied on the application of core principles from community-based participatory research (CBPR). Effective partnerships were achieved by involving all stakeholders and by addressing barriers in each phase of development, including (1) assessment of the problem; (2) development of goals; (3) engagement of key stakeholders; (4) establishment of the research agenda; and (5) dissemination of research findings.

Conclusions

Including safety-net providers, specialty physicians, hospitals, and community stakeholders in all steps of development allowed us to respond to potential barriers and implement a navigated care model for the uninsured. This process, whereby we integrated principles from CBPR, may be relevant for future capacity-building efforts to accommodate the specialty care needs of other vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Uninsured/safety-net providers, integrated delivery system, community-based participatory research, demonstration project, access to care

Care for the uninsured and underinsured is largely provided by our nation's health care safety-net system comprised of providers who care for patients regardless of their ability to pay (Institute of Medicine 2000). Nevertheless, uninsured and underinsured adults have inadequate access to care, receiving fewer health screening, preventive, and specialty care services than privately insured patients (Ayanian et al. 2000; DeVoe et al. 2003; Wilper et al. 2008; Ayanian 2009). The demonstrated need for improved access and care delivery in the safety-net system has prompted increased federal funding (Hoadley, Felland, and Staiti 2004; Shi and Stevens 2007; Sack 2008), including 11 billion dollars to expand the capacity of federally qualified community health centers (CHCs) through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (HealthCare.gov 2010).

Increased federal support to CHCs may help improve the quality of primary care in the safety-net system (Shi and Stevens 2007); however, access to specialty care remains a challenge. One quarter of patient visits to CHCs result in a referral to a specialist (Cook et al. 2007); yet fewer specialists are participating in the care of vulnerable populations, and there is no clear system for patients or primary care physicians to access those who do provide care (Dunham et al. 1991; Reed, Cunningham, and Stoddard 2001; Hartwig 2002; Cunningham and May 2006). Continued reliance on a limited pool of specialty physicians results in long wait-times for appointments, and, subsequently, fragmented care plans, disease advancement, and overutilization of emergency departments and hospitals (Ayanian et al. 2002).

Models of engaging specialty physicians in the care of the uninsured and underinsured are emerging (Isaacs and Jellinek 2007; Blewett, Ziegenfuss, and Davern 2008; Darnell 2010). Prior studies suggest, however, that these models need to extend beyond improving reimbursement to address other reasons many providers have opted out of caring for the uninsured; these include feeling overwhelmed by administrative hassles; lack of provider autonomy within the program; and patient complexity, including psychosocial needs (Shortell and Hull 1996; Chaudry et al. 2003; Cunningham and O'Malley 2009).

One program, Project Access, is responding to these concerns by creating a network of specialists and hospitals willing to provide donated care for uninsured and underinsured patients and integrating this care through patient navigation (Cofer 2008). The model has been replicated in communities throughout the United States (Ablah, Wetta-Hall, and Burdsal 2004; Baker, McKenzie, and Harrison 2005). Core principles and processes of implementing Project Access may be relevant for policy makers seeking to increase the capacity of the safety-net system to accommodate the specialty care needs of the uninsured (Lavis et al. 2002) and of the growing number of Medicaid beneficiaries expected to enter the safety-net system in 2014, when legislation from PPACA takes effect.

Accordingly, we aimed to describe the 2-year process of developing and implementing Project Access in New Haven, Connecticut. Using a case-study approach, we report how the core principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) were applied to address barriers to participating in an expanded safety net for the uninsured, and ultimately, to engage community stakeholders in all phases of implementation of Project Access-New Haven (PA-NH), including (1) assessing the scope of the problem of access to specialty care for the uninsured; (2) defining the goals of the project; (3) engaging new providers in the safety net, including specialists in private practice; (4) establishing the evaluation and research agenda, including the review of early findings from the first 46 patients enrolled; and (5) disseminating and translating research findings (Israel et al. 2010). Deliberate attention to these key stages of implementation may facilitate the expansion of the safety-net system for vulnerable populations in communities nationwide.

Methods

Conceptual Framework: Core Principles Guiding Implementation

We were guided by a conceptual framework informed by principles from the field of CBPR (Israel et al. 2005). CBPR is an effective method for engaging stakeholders in capacity-building efforts aimed at improving health outcomes for vulnerable populations (Israel et al. 2010; Schmittdiel, Grumbach, and Selby 2010). CBPR is built on the principle that when consumers of the research are involved in all steps of the project, outcomes are more relevant to the community needs and, therefore, the community members are more likely to sustain the outcomes long after the research project is finished. Another hallmark of CBPR is its commitment to action or translating research into practice.

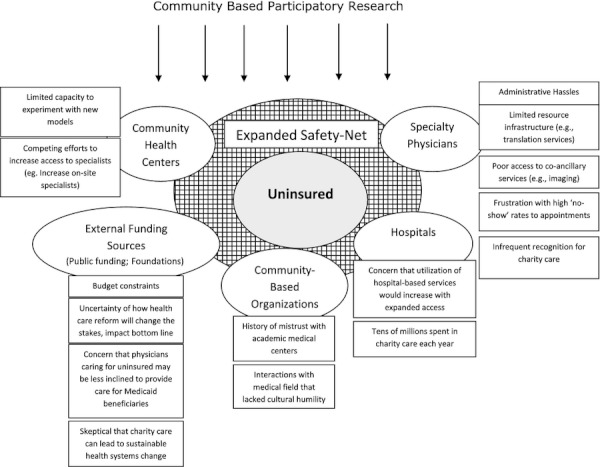

Our team hypothesized that the successful implementation of Project Access would depend on our identifying and building collaborative relationships with each of the groups within our community with a vested interest in the uninsured. Figure 1 outlines our model of an expanded safety net of providers for the uninsured, which includes the CHCs, individual physicians and practices, hospitals, and nonprofit service organizations intimately familiar with the needs of the uninsured, as well as local foundations and policy makers, who were driving local health care reform efforts. As the figure illustrates, we hypothesized several potential barriers that potentially would impact their willingness to participate in and/or support Project Access (Chaudry et al. 2003; Cunningham and O'Malley 2009). Importantly, these barriers were identified during the 2-year development phase and targeted as opportunities to apply core principles from CBPR to engage providers in the process of developing a program responsive to the challenges of caring for the uninsured.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework: Application of Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Partners’ Descriptions of Barriers to Participating in Expanded Safety Net for the Uninsured

Program Intervention: Project Access

Project Access is an organized system of specialty care for the uninsured. The model first emerged in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1996, and has since been replicated with substantial variation in program goals and capacity, in over 50 cities nationwide (Baker, McKenzie, and Harrison 2005). When optimally implemented, Project Access expands the safety net of providers caring for the uninsured to include the majority of community specialty physicians, most of whom are in private practice, along with all local hospitals, to provide donated care for the uninsured. At the core of the program are patient navigators who, using a patient-centered approach, help patients to (1) schedule medical appointments and tests; (2) access free or discounted prescription medication; (3) negotiate language and literacy barriers; and (4) connect with health-related resources. Additionally, patient navigators empower patients to be more proactive, facilitate communication among participating primary care and specialty physicians, and help execute the care plan. Several Project Access sites have demonstrated timely access to specialty care, patient and physician satisfaction, and a reduction in visits to the emergency department among enrollees.

Following a community assessment of the unmet health care needs of the residents of New Haven (described in detail below), we recognized that access to specialty care for the uninsured was a significant problem in our community. As we were in the midst of a recession and a vitriolic national health care debate, the Project Access model emerged as a potential intervention to address access to care in New Haven. The model appeared feasible as it involved coordinating volunteer health care; thus, all funding would be invested in patient navigation. Other Project Access sites had demonstrated that for every $1 invested in patient navigation, $4–$5 of donated care was rendered. Furthermore, patient navigation was increasingly being recognized as a potential method of improving quality and appropriate care utilization (Peikes et al. 2009).

Data Sources

To guide the process of implementing PA-NH, we applied a triangulation approach to understand the principles, tasks, and data needed to accomplish each implementation step (Yin 1999). We considered multiple data sources to inform these steps, including CHC and hospital administrative records; in-depth interviews with both early supporters and skeptics of the model; site visits to other Project Access programs; and policy briefs and health services literature related to access to care for the uninsured. In addition, to affirm program fidelity in reaching the targeted population, we performed a preliminary review of data collected from patient surveys. In the results below, we describe how these data sources were used to inform each implementation step. The Institutional Review Board of Yale University approved this study.

Results

From August 2008 through August 2010, a team comprised of academic researchers, primary care physicians, specialty physicians in private practice, and advocates for the underserved partnered to form PA-NH, a 501©3 organization aimed at improving access to specialty care among the uninsured. Table 1 describes the core components of this process, which are elaborated in turn.

Table 1.

Process Used to Guide Implementation of a Navigated Care Model to Expand Access to Specialty Care for the Uninsured

| Steps | CBPR Principle | Tasks | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess the scope of the problem | Build on strengths and resources within the community | • Identify and describe target population | • Policy briefs; community needs assessments |

| • Understand community perceptions about access | • Administrative books and databases | ||

| • Define wait-times for specialty care | • In-depth interviews | ||

| 2. Engage key stakeholders | Invest in long-term and robust relationships with partners | • Engage leaders representing the uninsured communities in New Haven | • In-depth interviews |

| • Engage a volunteer core of private and hospital-based physicians | • Debriefing of meetings and community presentations | ||

| • Literature review | |||

| 3. Define project goals | Foster co-learning and capacity building among all partners | • Learn community's prior experience with efforts to improve access | • In-depth interviews |

| • Learn from similar models | • Surveys | ||

| 4. Establish evaluation and research agenda | Integrate and achieve a balance between knowledge generation and intervention for mutual benefit of all partners | • Align research goals with program evaluation and quality improvement goals | • In-depth interviews |

| • Establish database | • Site visit | ||

| • Early assessment of enrolled patients’ health and health-related needs | • Literature review | ||

| • Surveys | |||

| 5. Disseminate research findings | Disseminate results to all partners and involve them in the dissemination process | • Consider professional and lay media for disseminating results | • Input from stakeholders on type and presentation of data |

| • Ensure that findings are in plain language | |||

| • Develop website | |||

| • Develop policy briefs | |||

| • Reports to funders and other stakeholders |

Assess the Scope of the Problem

CBPR Builds on Strengths and Resources within the Community

We conducted a comprehensive, systematic baseline needs assessment of the community, including insurance trends, problems associated with lack of insurance, the quality of access to primary and specialty care, and reliance on safety-net providers (e.g., emergency departments and hospitals) in New Haven. We used multiple sources of data, including: (1) systematic review of the literature; (2) key informant interviews with eleven members of the medical community of New Haven; (3) review of administrative data systems from one CHC to define wait-times for primary care and specialty care appointments; and (4) reports from other community assessments and from local policy organizations(Hartwig 2002; Connecticut Health Policy Brief 2009).

From this community needs assessment, it emerged that primary care in New Haven was robust; despite the growing number of uninsured, the CHCs were able to accommodate the primary care needs of the uninsured. However, there was frustration with long wait-times for specialty appointments and broken communication systems among primary care providers and specialists. From key informant interviews, we learned that the rising number of uninsured was disproportionately affecting Latino and African American adults, and that this further contributed to health care disparities. They highlighted several common barriers experienced by these groups to accessing care for both acute and chronic medical conditions, including transportation and language interpretation, along with mistrust of the medical system and fear of excessive medical bills.

An assessment of the baseline characteristics of the first 46 patients enrolled in PA-NH, from September 2010 to December 2010, supported the data from the key informant interviews (Table 2). The mean age of this early group of enrollees in PA-NH was 42.8 years. Most were either Latino (76.1 percent) or African American (13 percent); half were unemployed. Chronic illness was prevalent (52.2 percent), and over one quarter had an emergency department visit in the past year. Nearly 70 percent avoided care due to cost, and most (56.6 percent) experienced difficulty accessing care. In addition, patients faced challenges in adhering to the care plan, as evidenced by 43.5 percent not filling a prescription because of cost. The most common self-reported barriers to access in the year prior to enrollment were cost (52.2 percent), language barriers (26.1 percent), transportation (26.1 percent), work-schedule conflicts (13.0 percent), and child care issues (6.5 percent).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of First 46 Patients Enrolled in PA-NH

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 42.8 ± 13.1 years |

| Gender (%female) | 23 (50.0%) |

| Race | |

| White | 5 (10.9%) |

| Black | 6 (13.0%) |

| Asian | 1 (2.2%) |

| Ethnicity Latino/Hispanic | 35 (76.1%) |

| Education | |

| No or some high school | 23 (50.0%) |

| High school | 16 (34.8%) |

| Any college | 7 (15.2%) |

| Employment/assistance | |

| Current employment | |

| Not working | 23 (50.0%) |

| Part time | 18 (39.1%) |

| Full time | 5 (10.9%) |

| Among working patients, employer offers insurance (n = 23) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Public assistance received in the past 12 months* | |

| None | 24 (52.2%) |

| Food stamps | 9 (19.6%) |

| Cash assistance (Welfare) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Women infants and children (WIC) | 9 (19.6%) |

| Unemployment | 7 (15.2%) |

| Disability | 2 (4.3%) |

| Health insurance | |

| Ever had health insurance | 16 (34.8%) |

| Among those with prior health insurance, period without insurance (n = 16) | |

| <3 months | 0 (0%) |

| 3–6 months | 2 (12.5%) |

| 6–12 months | 1 (6.3%) |

| 1–3 years | 7 (43.8%) |

| >3 years | 6 (37.5%) |

| Reason for being uninsured* | |

| Not working | 18 (39.1%) |

| Cannot afford premiums | 22 (47.8%) |

| Company does not offer | 10 (21.7%) |

| Have not had health problems/need | 0 (0%) |

| Preexisting condition | 1 (2.2%) |

| Do not know how to get insurance | 0 (0%) |

| Works part time | 1 (2.2%) |

| Other | 9 (19.6%) |

| Current health needs | |

| Type of specialty service needed | 1. Gastroenterology |

| 2. Urology | |

| 3. Cardiology | |

| 4. Orthopedics | |

| 5. ENT | |

| Amount of time with current complaint | |

| <1 month | 10 (21.7%) |

| 1–3 months | 10 (21.7%) |

| 3–6 months | 6 (13.0%) |

| 6–12 months | 2 (4.3%) |

| >1 year | 18 (39.1%) |

| Health status | |

| Number of days missed from work/activities in past 30 days due to illness | |

| 0 | 10 (21.7%) |

| 1–6 | 14 (30.4%) |

| >7 | 21 (45.6%) |

| Comorbid medical conditions* | |

| Hypertension | 13 (28.3%) |

| Diabetes | 7 (15.2%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 11 (23.9%) |

| Asthma | 3 (6.5%) |

| Depression | 2 (4.3%) |

| Arthritis | 0 (0%) |

| Coronary heart disease | 2 (4.3%) |

| Chronic lung disease (COPD) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Cancer | 2 (4.3%) |

| Stroke | 1 (2.2%) |

| Autoimmune/inflammatory disease | 2 (4.3%) |

| None of the above | 22 (47.8%) |

| Health care utilization | |

| Usual source of care* | |

| Clinic/health center | 39 (84.8%) |

| Private office | 2 (4.3%) |

| Emergency department | 2 (4.3%) |

| None | 3 (6.5%) |

| Is there one doctor or health professional you usually see? | |

| Yes | 29 (63.0%) |

| No | 17 (37.0%) |

| In past 12 months, number of emergency department visits† | |

| 0 | 31 (67.4%) |

| 1–3 | 10 (21.7%) |

| >4 | 3 (6.5%) |

| In past 12 months, number of hospitalizations | |

| 0 | 40 (87.0%) |

| 1–3 | 6 (13.0%) |

| >4 | 0 (0%) |

| In past 12 months, number of times desired to see a doctor but did not† | |

| 0 | 21 (45.7%) |

| 1–5 | 20 (43.5%) |

| >6 | 4 (8.6%) |

| In past 12 months, ease of getting desired care | |

| Easy | 11 (23.9%) |

| Somewhat easy | 9 (19.6%) |

| Somewhat difficult | 17 (37.0%) |

| Difficulty | 9 (19.6%) |

| Ever avoided health services due to cost | |

| Yes | 32 (69.6%) |

| No | 14 (30.4%) |

| Ever not taken a prescription medication because of cost | |

| Yes | 20 (43.5%) |

| No | 26 (56.5%) |

| Barriers to seeing physician | |

| Transportation | 12 (26.1%) |

| Work schedule conflicts | 6 (13.0%) |

| Cost | 24 (52.2%) |

| Language barrier | 12 (26.1%) |

| Child care | 3 (6.5%) |

| Do not know how to get appt | 1 (2.2%) |

| None | 12 (26.1%) |

Notes.

Categories not mutually exclusive; percentages may not sum to 100%.

Due to missing data, percentages may not sum to 100%.

To address these barriers, PA-NH has hired all bilingual patient navigators, who can culturally identify with the challenges faced by the local community. Patient navigators do not have a clinical background, but they have excellent interpersonal skills, are organized and proactive, and have a passion for advocacy. All patient navigators receive education about local health-related resources and attend a 3-day training workshop given by the Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute in New York City. In addition, to address language barriers, hospitals are providing free telephone interpretation services for all PA-NH physician visits, and all materials are produced in both English and Spanish––the two most common languages spoken by the uninsured in New Haven.

Engage Key Stakeholders

Invest in Long-Term and Robust Relationships with Partners

Our process for engaging key stakeholders in the implementation of Project Access was threefold. First, we interviewed leadership of the two New Haven CHCs and three nonprofit organizations providing social services to many African American and Latino residents in New Haven, groups who were disproportionately affected by lack of insurance. We also met with the deputy mayor, and two senior administrators from the New Haven Department of Health, along with the philanthropy arms of two local businesses who were committed to helping vulnerable populations. We conducted in-depth interviews with these community leaders to (1) understand their perspective of the health care needs of the uninsured; (2) inform them about Project Access––as it exists in other communities; and (3) reconcile barriers to participation.

Second, we engaged local health care leadership and potential volunteer providers. We met with senior administration of both local hospitals (Yale New Haven Hospital and the Hospital of Saint Raphael), including the chief executive and operating officers, chairs of medicine and surgery, and chiefs of specialty departments, including radiology, pathology, and anesthesiology. We gave formal presentations about the uninsured and Project Access at medical grand rounds and section meetings. We used email to engage individual specialty providers, and we published articles in medical newsletters and in the lay press. Finally, the members of our team who were also members of the New Haven County Medical Association reached out, individually, to their constituency.

Third, we engaged funders. While other Project Access programs were started with large federal or foundation grants, such funds were not available to us. We focused on local foundations, hospitals, and the medical community to support Project Access. These groups were most informed about the downstream effects of limited access to care for the uninsured. Several local foundations have missions to fund projects that reduce health care disparities and/or focus on improving social determinants of health. Hospitals were potential funders as well, as implementation of Project Access had the potential to reduce emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Finally, we recognized that substantive financial support from the medical staffs of both hospitals would serve the dual goals of educating our physician pool about the program and its projected merits, while simultaneously building investment in the outcomes of the project.

In engaging funders early on in the development process, we learned about state-wide goals for health care reform and about the priorities of some private foundations. This exchange was critical to informing the program's goals and outcomes of interest. During a meeting with the executive directors of seven local and state foundations, in which we presented Project Access and elicited feedback, we learned that funders were concerned with how this program might unintentionally worsen access to care for Medicaid beneficiaries, whereby preference for caring for PA-NH patients might lead physicians to drop out of caring for Medicaid beneficiaries. We appreciated this concern, and since then, a main goal of PA-NH is to reach out to providers who are not currently accepting Medicaid patients but also to ultimately expand the program to include the Medicaid population. This latter commitment has resulted in PA-NH engaging in a demonstration project with both local hospitals to study the impact of the program on the uninsured and its potential expansion to Medicaid beneficiaries. Ultimately, input from local foundations, hospitals, and physicians helped us to develop a model that was responsive to the health and health-related needs of the uninsured in New Haven, and that considered the potential unintended consequences of the model. Since that meeting, we have continued to coordinate PA-NH with other local health care reform efforts with the aim of optimizing outcomes for all vulnerable populations.

Define the Goals of Project Access

CBPR Fosters Co-learning and Capacity Building among All Partners

To define the goals of the program, we aggregated the local and external experiences with access to care for the uninsured. For example, from our discussions with two community organizations, we learned that communication among primary care and specialty physicians was poor. In bringing together physicians from primary care and specialty practices, each learned of the others’ frustrations. Primary care providers often did not receive standard consultation letters from specialists. Specialists complained that little patient information was sent to them, and that it was difficult to reach the provider on the phone. These discussions challenged PA-NH to develop new systems to improve communication among providers. We developed new referral forms, requested emails and direct phone numbers of all participating providers, and developed a system whereby correspondence among providers goes through the patient navigators, ensuring the transfer and receipt of referral and consultation letters.

Establish Evaluation and Research Agenda

CBPR Integrates and Achieves a Balance between Knowledge Generation and Intervention for Mutual Benefit of All Partners

The research goals of Project Access are aligned with evaluating and improving the quality of the program, and supporting the sustainability and generalizability of the model. The research agenda consists of four parts: (1) identification of the sociodemographic characteristics, health and health-related needs, and perceived barriers to access among the uninsured; (2) comparison of wait-times and show-rates to specialty appointments before and after program implementation; (3) assessment of utilization and cost of health services rendered through the program; and (4) study of physician satisfaction with the program.

There are several challenges to collecting data in this population. First, there is no integrated health information technology (IT) system, making it difficult to track utilization across hospitals and CHCs. Second, there is substantial variation among the CHC administrative record systems, and they are not easily queried; much of the data are collected by hand. As a result, it is difficult to compare and to trend referral wait-times and show-rates to appointments. Third, primary data collection must be balanced with time and space constraints, as often this adds responsibility to direct service providers. We are working to overcome these barriers. For example, to track utilization, we collect claims (cost set to zero) generated by specialty physicians, clinics, hospitals, and other volunteer providers. We have invested in an IT system, recommended by other Project Access sites, to house demographic information about patients, and to track process measures and outcomes, such as wait-times. We developed patient questionnaires, piloted in both English and Spanish, that are administered by a patient navigator; as requested by the patient navigators, responses to surveys are documented on paper and then entered into the database by a research assistant. For the demonstration project, we have budgeted for a full-time researcher, which will allow us to collect follow-up data on patient outcomes, measure physician satisfaction, and assess whether the program is effective in reducing hospital expenditures of uncompensated care.

Disseminate and Translate Research Findings

CBPR Disseminates Results to All Partners and Involves Them in the Dissemination Process

We have developed ongoing dissemination processes for sharing our findings with the local community, the professional community, and among policy makers, and past and future funders. These dissemination strategies were informed by the literature and other Project Access sites. In the local community, we are sharing key results and anecdotal patient stories with our partners in the form of newsletters, briefs, and frequent in-person meetings. We developed a website with information for patients and providers (http://www.pa-nh.org). For the medical community, we have presented Project Access at medical conferences and workshops on urban planning initiatives, and we are finalizing a systematic review of the literature on physician attitudes toward caring for the uninsured and publicly insured. For policy makers, we have developed relationships with state and U.S. representatives of Congress, have created policy briefs, served on health care reform panels, and regularly updated both officials and their staff about Project Access. For funders, we report program activity and efforts toward expanding to the Medicaid population. In addition, we report the cumulative dollar value of the care and services that are rendered to PA-NH patients, demonstrating similar leveraging of funding dollars to donated care ($1/$4–$5) as other Project Access sites.

Discussion

Under the PPACA, dozens of demonstration projects will be implemented to test new models of providing health care, such as accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes. These demonstration projects provide important opportunities to study the impact of the project on the health care system (Rittenhouse, Shortell, and Fisher 2009). Yet how these projects will be implemented is not clear. Experience with managed care plans in the 1990s suggests that physicians, hospitals, and consumers may not embrace efforts to coordinate care (Shortell and Hull 1996; Feldman, Novack, and Gracely 1998). One hypothesis is that these groups were never included in the design, conduct, or evaluation of the care plan. Our experience in using CBPR to implement PA-NH suggests that early inclusion and partnership are key for generating support and commitment to the model.

In applying principles from CBPR, we were able to develop and implement a coordinated care model to improve access to specialty care for the uninsured. We built partnerships with an expanded safety-net of providers by engaging them in the process of designing, funding, evaluating, and disseminating results about the program. We believe that inclusion in all phases of the implementation process will have important implications for the programs’ effectiveness and sustainability.

We involved policy makers at the front end of our work. We believe that linking grassroots efforts with local and state health policy agendas can help increase visibility, investment in outcomes, and ultimately, if effective, expansion and translation for other populations. Thus, from the beginning, PA-NH has been poised to deliver results on outcomes relevant to policy makers, including a sustained commitment from volunteer physicians, a positive impact on health disparities, improved patient outcomes, and a reduction in avoidable emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and readmissions. These data will help inform whether PA-NH is truly having an impact on the health care system; if so, then we may be better able to convince local legislators to support models that include patient navigation. One example may be to consider including patient navigators as part of the patient-centered medical home.

Lessons learned from the implementation of PA-NH may be particularly useful for other communities seeking to expand access to specialty care for their uninsured population (Grol and Jones 2000; Foy, Eccles, and Grimshaw 2001). First, the expanded infrastructure of physicians and providers assuming responsibility for the care of the uninsured ensures that no one physician, practice, or hospital is overwhelmed. We have found that allowing physicians to dictate the terms of their involvement (i.e., number of PA-NH patients they see per month) has helped recruitment. Second, putting patient navigators at the center of the care plan has been well accepted by patients and providers. As two-thirds of PA-NH patients are Latino, and 26 percent cite language as a barrier to accessing care, patient navigators must be bilingual but also bicultural. Data suggest that for vulnerable populations, having a patient navigator who can identify with them helps build trust and adherence to the care plan (Jandorf et al. 2006; Petereit et al. 2008). Moreover, physicians are more inclined to participate in PA-NH, as they can focus on addressing the medical needs of the patient, while patient navigators address the health-related needs of patients––which tend to be higher among patients with limited resources (Ablah, Wetta-Hall, and Burdsal 2004).

Our description of the process of implementing Project Access has limitations. As with any single-location study, lessons learned may be considered too idiosyncratic to the specific circumstances in which the case took place. However, because one of our earliest goals was to potentially expand Project Access for Medicaid beneficiaries, we used established principles and overarching concepts to guide our process of engagement. In so doing, we believe that this process has wider applicability for other communities. Another limitation is that it is too early to determine whether Project Access will meet its stated goals. However, preliminary results demonstrate that we are reaching our targeted population; rigorous evaluation methods are established to study the programs’ impact.

In summary, there is increasing interest in coordinated models to improve care delivery for vulnerable populations. Yet it is unclear who will be the drivers of these health system changes and what steps will be required for their successful implementation. Important lessons may be derived from our experience applying principles from CBPR to implement PA-NH that should be considered by communities and policy makers seeking new methods for increasing access to specialty care for vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Authors ESS, MSP, and OJW are funded through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. Research for this community project was supported by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation.

Disclaimers: None.

Disclosures: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Ablah E, Wetta-Hall R, Burdsal CA. “Assessment of Patient and Provider Satisfaction Scales for Project Access”. Quality Management in Health Care. 2004;13(4):228–42. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanian JZ. 2009. “America's Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care.” Statement before the Committee on Ways and Means, United States House of Representatives Public Hearing on Health Reform in the 21st Century: Expanding Coverage, Improving Quality and Controlling Costs. March 11.

- Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. “Unmet Health Needs of Uninsured Adults in the United States”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(16):2061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanian JZ, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Gaccione P. “Specialty of Ambulatory Care Physicians and Mortality among Elderly Patients after Myocardial Infarction”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(21):1678–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker GK, McKenzie AT, Harrison PB. “Local Physicians Caring for their Communities: An Innovative Model to Meeting the Needs of the Uninsured”. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2005;66(2):130–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blewett LA, Ziegenfuss J, Davern ME. “Local Access to Care Programs (LACPs): New Developments in the Access to Care for the Uninsured”. Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(3):459–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudry RV, Brandon WP, Thompson CR, Clayton RS, Schoeps NB. “Caring for Patients under Medicaid Mandatory Managed Care: Perspectives of Primary Care Physicians”. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(1):37–56. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofer JB. “Project Access: Giving Back at Home”. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. 2008;93(1):13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Health Policy Brief. Danbury and Windham County Lead the State in Uninsured Rates. New Haven, CT: Connecticut Health Policy Project; 2009. No.50.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cook NL, Hicks LS, O'Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. “Access to Specialty Care and Medical Services in Community Health Centers”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1459–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham P, May J. “Medicaid Patients Increasingly Concentrated among Physicians”. Tracking Report. 2006;16:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PJ, O'Malley AS. “Do Reimbursement Delays Discourage Medicaid Participation by Physicians?”. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):w17–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JS. “Free Clinics in the United States: A Nationwide Survey”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(11):946–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe JE, Fryer GE, Phillips R, Green L. “Receipt of Preventive Care among Adults: Insurance Status and Usual Source of Care”. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):786–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham NC, Kindig DA, Lastiri-Quiros S, Barham MT, Ramsay P. “Uncompensated and Discounted Medicaid Care Provided by Physician Group Practices in Wisconsin”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265(22):2982–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DS, Novack DH, Gracely E. “Effects of Managed Care on Physician-Patient Relationships, Quality of Care, and the Ethical Practice of Medicine: A Physician Survey”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(15):1626–32. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy R, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. “Why Does Primary Care Need More Implementation Research?”. Family Practice. 2001;18(4):353–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Jones R. “Twenty Years of Implementation Research”. Family Practice. 2000;17(suppl 1):S32–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.suppl_1.s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig K, Harris M. 2002. “The Uninsured and Publicly Insured's Access to Specialty Care in New Haven, Connecticut” [accessed December 1, 2010]. Available at: http://www.cga.ct.gov/ph/medicaid/mmcc/minutes/Care-NewHaven.doc.

- HealthCare.gov. 2010. “Community Health Centers and the Affordable Care Act: Increasing Access to Affordable, Cost Effective, High Quality Care” [accessed on December 1, 2010]. Available at http://www.healthcare.gov/news/factsheets/increasing_access_.html.

- Hoadley JF, Felland LE, Staiti A. 2004. “Federal Aid Strengthens Health Care Safety Net: The Strong Get Stronger.” Center for Studying Health Systems Change, Issue Brief 80 [accessed December 1, 2010]. Available at: http://hschange.org/CONTENT/669/

- Institute of Medicine. America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs SL, Jellinek P. “Is There a (Volunteer) Doctor in the House? Free Clinics and Volunteer Physician Referral Networks in the United States”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(3):871–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, Reyes AG, Clement J, Burris A. “Community-Based Participatory Research: A Capacity-Building Approach for Policy Advocacy Aimed at Eliminating Health Disparities”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jandorf L, Fatone A, Borker PV, Levin M, Esmond WA, Brenner B, Butts G, Redd WH. “Creating Alliances to Improve Cancer Prevention and Detection among Urban Medically Underserved Minority Groups. The East Harlem Partnership for Cancer Awareness”. Cancer. 2006;107(8 suppl):2043–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Ross SE, Hurley JE, Hohenadel JM, Stoddart GL, Woodward CA, Abelson J. “Examining the Role of Health Services Research in Public Policymaking”. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(1):125–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. “Effects of Care Coordination on Hospitalization, Quality of Care, and Health Care Expenditures among Medicare Beneficiaries: 15 Randomized Trials”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(6):603–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petereit DG, Molloy K, Reiner ML, Helbig P, Cina K, Miner R, Spotted Tail C, Rost C, Conroy P, Roberts CR. “Establishing a Patient Navigator Program to Reduce Cancer Disparities in the American Indian Communities of Western South Dakota: Initial Observations and Results”. Cancer Control. 2008;15(3):254–9. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MC, Cunningham P, Stoddard J. 2001. “Physicians Pulling Back from Charity Care.” Issue Brief. Center for Studying Health Systems Change, Issue Brief 42 [accessed December 1, 2010]. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/356/356.pdf. [PubMed]

- Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. “Primary Care and Accountable Care—Two Essential Elements of Delivery-System Reform”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(24):2301–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack K. “Community Health Clinics Increased during Bush Years”. New York Times. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Schmittdiel JA, Grumbach K, Selby JV. “System-Based Participatory Research in Health Care: An Approach for Sustainable Translational Research and Quality Improvement”. Annals of Family Medicine. 2010;8(3):256–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Stevens GD. “The Role of Community Health Centers in Delivering Primary Care to the Underserved: Experiences of the Uninsured and Medicaid Insured”. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2007;30(2):159–70. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000264606.50123.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Hull KE. “The New Organization of the Health Care Delivery System”. Baxter Health Policy Review. 1996;2:101–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU. “A National Study of Chronic Disease Prevalence and Access to Care in Uninsured U.S. Adults”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149(3):170–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. “Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research”. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1209–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.