Abstract

Religious institutions in Asian immigrant communities are in a unique position to confront the challenges of the HIV epidemic for the populations they serve. However, there has been little research on whether these institutions are willing or able to take a role in HIV prevention. This article reports on findings from a qualitative study of three Asian immigrant religious institutions in New York City (a Buddhist temple, a Hindu temple, an Islamic center/mosque) that are part of a larger study of Asian immigrant community institutions and their response to the HIV epidemic. Several prominent themes arose that formed the basis of a preliminary theoretical framework describing the way Asian immigrant religious institutions may evaluate their role in HIV prevention. The interview data indicate that the institutions take a stance of “conservative innovation,” weighing their role as keepers of morality and religious tradition against the changing needs of their communities and then adjusting their practices or positions incrementally (to varying degrees) to stay responsive and relevant.

Keywords: HIV, Religion, Institutions, Asian, Immigrants

INTRODUCTION

In the early years of the epidemic, religious institutions in the US were essentially uninvolved in the fight against AIDS. Although some religious institutions participated in the care of AIDS patients, prevention – even within high prevalence communities – was rarely addressed. Recent changes are evident, particularly among Black churches. However, among Asian religious institutions, their interest or skills to address HIV/AIDS, have not been explored. HIV, sex (particularly outside of marriage), homosexuality, and drug use are generally taboo subjects in Asian communities (Chin and Kroesen, 1999; Choi et al., 1995; Eckholdt et al., 1997; Kang et al., 2000; Sy et al., 1998; Yoshikawa et al., 2001; Yoshioka and Schustack, 2001). In addition, there may be an unrealistic perception of minimal risk.

As of December 2002, at least 960 Asians and Pacific Islanders (A&PIs) in New York City (NYC) had been diagnosed with AIDS (NYCDOH, 2002; 2004), accounting for a substantial portion (14%) of the 6,924 cumulative A&PI AIDS cases in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004). Upward trends are evident both nationally and in NYC: according to the most recent data available, there were 471 new A&PI AIDS diagnoses in the US in 2002, compared to 437 in 2001 (a rise of 7.8%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). In NYC, there were 62 new A&PI diagnoses in 2002, compared to 49 in 2001 – representing an increase of 26.5%, more than three times the national rate of increase (NYCDOHMH, 2003; 2004). Reflecting this increase, the estimated number of NYC A&PIs living with HIV/AIDS in that period rose by 18.6% (NYCDOHMH, 2004). Where country of birth is known, approximately 66% of A&PI AIDS cases in NYC are among immigrants, primarily from China, the Philippines and India NYCDOH, 2001).

AIDS has reached epidemic proportions in parts of the Asia-Pacific region (with an estimated 7.2 million people living with the virus as of the end of 2003), and is rapidly escalating in countries such as China and India, which are the most heavily populated countries in the world (MAP Network, 2004). The combination of the rapid spread of HIV in Asia, continued high levels of bi-directional migration between Asia and the US, and potential sexual network linkages between the infected and uninfected suggests that HIV/AIDS among A&PIs in the US will continue to rise, especially in the absence of a response from Asian immigrant community institutions.

Language and cultural barriers, as well as discrimination, isolate many immigrants from the wider society. They therefore rely heavily on immigrant community institutions to obtain social, economic and other supports (Basch et al., 1994; Kim, 1987; Zhou, 1992). Community institutions are well positioned to influence community members’ understanding of health and disease and to disseminate information within these populations. In the case of HIV, this role is especially important because of the social stigma surrounding HIV and the potentially dire health consequences of not understanding how to prevent transmission of the virus.

Religious institutions, in particular, are very influential in Asian immigrant communities (Min, 2002) and thus uniquely positioned to confront the challenges of HIV. Because of these institutions’ substantial role in issues related to culture, morals, and social relations, they can shape social understanding of HIV and related issues. The opportunity for religious institutions to take on a role in HIV has been enhanced by recent governmental efforts to encourage increased involvement of faith-based institutions in HIV-related activities (AIDS Action, 2003). Yet little is known about HIV-related attitudes and policies among Asian religious institutions in the US. Only one study of Asian religion and HIV in the US, which explored how Buddhist teachings could be integrated with HIV education, was identified in the public health literature (Loue et al., 1999). The lack of literature on religious institutions and HIV is part of the general lack of attention to community-level HIV prevention approaches (Kelly, 1999)4.

Because the conversation about HIV is so new, or often non-existent, in Asian immigrant communities, community-level interventions are needed to encourage acknowledgment and discussion of HIV before interventions can effectively address HIV risk reduction. Asian religious institutions’ influence on immigrant community values and social norms makes them a potentially key partner in community-level interventions to increase dialogue about HIV in Asian immigrant communities.

Data for this paper are derived from a larger exploratory study of the role of community institutions in HIV prevention in Chinese and South Asian (specifically, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi) immigrant communities, which are the two largest A&PI groups in NYC, together composing more than 70% of the city’s A&PI population (AAFNY, 2003). Here, we focus on religious institutions only. Based on 17 in-depth qualitative interviews with leaders and members of one Chinese and two South Asian immigrant religious institutions, we address how the leaders and members of these religious institutions view their organizations’ role in addressing HIV prevention. We also describe a preliminary theoretical framework derived from our data of how these religious institutions weigh decisions related to confronting the problem of HIV in their communities.

METHODS

The internal diversity and geographic dispersal of the Chinese and South Asian populations, as well as the lack of precedents for studying Asian immigrant institutions from a public health perspective, encouraged a multi-method approach. The procedures described below were used in our larger study on Asian immigrant institutions, which included the sample of religious institutions described in this paper. IRB approval was obtained prior to starting data collection.

Procedures

1. Recruitment of Institutions

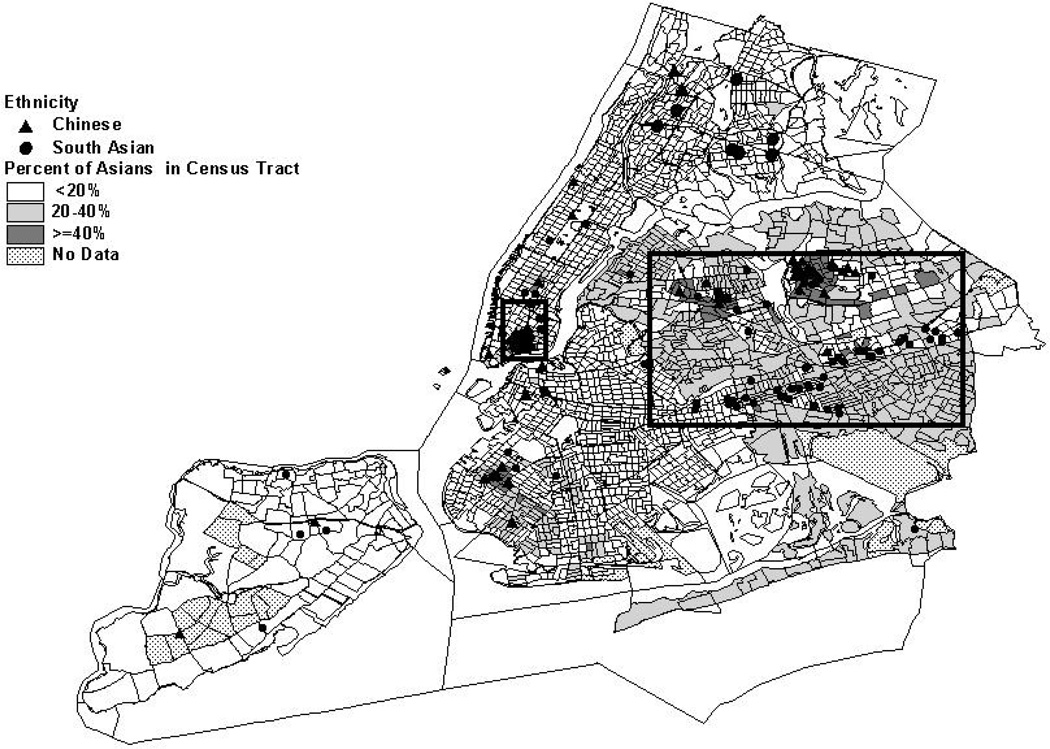

Using Internet listings, ethnic service and organization directories, and ethnic “yellow pages,” we generated a database of 213 South Asian and 316 Chinese community-based immigrant institutions in NYC. These institutions were classified into nine categories according to their primary purpose: business association, charitable, cultural, healthcare/social service, media, political, professional, religious and social. Religious institutions made up the largest category of institutions identified: 42% (n=132) among Chinese institutions and 47% (n=100) among South Asian institutions. Maps showing the distribution of the religious institutions overlaying A&PI population density in NYC are shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Chinese & South Asian Religious Institutions in New York City

Figure 2.

Chinese & South Asian Religious Institutions in Chinatown (Manhattan)

Figure 3.

Chinese & South Asian Religious Institutions in Queens

A randomly ordered list of institutions was generated for each category of institution and for the two population groups. Using these lists, 20 institutions (10 Chinese and 10 Indian) that were deemed eligible through telephone screening were randomly selected for in-depth study. Institutions with little or no formal structure, no discernable social agenda, and a reach of fewer than 100 people were ineligible to participate in the in-depth study. No religious institutions were excluded based on the first two criteria; they tended to be more structured and service-oriented than most of the other types of institutions in our database. Of the 20 institutions selected, we aimed to include four religious institutions – 1 Chinese Buddhist, 1 Chinese Christian, 1 Indian Hindu, and 1 South Asian Islamic. To recruit institutions for in-depth interviews, we mailed a letter and information packet, followed by a telephone call approximately two weeks later to request a face-to-face meeting. Of the religious institutions approached for the study, only the Chinese Christian church refused. In fact, 3 Chinese churches refused participation, primarily due to the HIV focus of the study. Although we were able to recruit a Chinese church eventually, the recruitment delay precluded their inclusion in the analysis presented here.

2. Recruitment of Individual Participants Within Institutions for In-Depth Interviews

Within each institution, we aimed to interview five leaders or members.5 Our selection of interview participants was based on recommendations from the institutions’ leadership, referrals from members interviewed or personal contacts at institutional events. In most instances, the selection process involved having institution leaders pre-screen potential respondents for willingness to participate in the interview; thus, we do not have an accurate report of refusal rates. Although this process biased the selection towards institution leaders and more active members, because of their influence within their organizations, they are perhaps the most relevant respondents for understanding institutional willingness to participate in HIV prevention activities. Within these selection constraints, we sought to obtain diversity in participants’ gender, age, and institutional role.

3. Interview Protocol

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted by two trained multi-lingual interviewers who obtained written consent from respondents prior to the interview. Interviews lasted an average of 90 minutes and were followed by a nine-item true-false HIV knowledge questionnaire, which was developed specifically for this study to yield variation among a population that has a relatively low HIV knowledge level. The questionnaire covered knowledge about items such as mother-to-child transmission, how longer after infection HIV antibodies can be detected, whether a person with HIV can be identified based on physical appearance, risk of infection through casual contact, the effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission, and whether there is a cure for HIV. Participants were provided with a $25 incentive for their participation. Interview questions covered organizational characteristics, reputation and influence and participant’s level of involvement in the organization; attitudes and beliefs about social issues such as gender roles and ethnicity; knowledge and attitudes about HIV; assessment of the barriers to and facilitators of the organization’s involvement in HIV prevention; views on the best approaches to conducting HIV prevention education; and sociodemographic characteristics.

All of the interviews with the South Asian institutions were conducted in English, except one that was conducted in Urdu. Interviews with the Chinese institutions were conducted in Mandarin. Because there were a large number of Chinese-speaking respondents, both the in-depth interview guide and knowledge questionnaire were translated into Chinese. The translator discussed intended meanings and nuances with the principal investigator as translations were prepared. To allow for comparison of quantitative scores on the HIV knowledge questionnaire across respondents, and because assessments of true-false statements are particularly sensitive to word choice, the Chinese version of the questionnaire was back-translated into English to verify the comparability of the Chinese and English versions. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. The non-English interviews were translated during the transcription process by the multi-lingual interviewers.

Data Analysis

A preliminary codebook was developed based on four interviews, after which the five authors of the paper independently coded the same two interviews and then met to discuss the coding process and refine the codebook (MacQueen, 1998). Following revisions to the codebook, the remaining interviews were coded by two members of the research team in two rounds. There were 92 codes grouped into 10 main categories. Examples of codes include: “member reaction to HIV involvement,” “helping a person worried about HIV,” and “best approaches to HIV education.” Our coding process and discussions among the coders led to the emergence of new issues and themes, thereby reaping the most important advantage of multiple coding: “its capacity to furnish alternative interpretations …” (Barbour, 2001:1116). Research team members prepared interview summaries using a standard template, met to discuss coding disagreements, and drafted analytic memos throughout the coding process. This analytic process modeled on the grounded theory approach (Corbin, 1986) led to the development of a preliminary theoretical framework described later in the Results section below.

Institution Characteristics

Table I summarizes the organizational characteristics of the religious institutions. The table is followed by a brief description of each institution. We omitted some specific information about the institutions and respondents to preserve their anonymity.

Table I.

Characteristics of the Three Religious Institutionsa

| Buddhist Temple | Hindu Temple | Islamic Center/Mosque | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Members | Approximately 300; about 15 monks and nuns in residence. | 20,000 on mailing list. | 4,000 to 5,000 members (informally defined); social service unit sees 5 to 6 clients each day. |

| Location | Manhattan | Queens | Queens |

| Geographic Reach (community served) | New York City metropolitan area, but mostly the local Chinatown neighborhood | Tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, Connectictut) | New York City metropolitan area |

| Main Activities |

|

|

|

| Past or Current Health-Related Activities | Collaborates annually with NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to administer free flu shots to the community. | Annual health fair and blood donation drive | Sporadic health education lectures and workshops for members; referral of clients to appropriate service providers as required. |

| Past or Current HIV-Related Activities | None | HIV prevention video shown at annual health fair | Some HIV awareness training for some staff |

Certain institution characteristics have been omitted to preserve anonymity.

Buddhist Temple

Founded 22 years ago, the Buddhist temple is located in a Manhattan Chinatown neighborhood of mostly first-generation Fujianese immigrants and provides a full-range of religious services. The temple has an estimated membership of 300, coming from both the immediate neighborhood and from other parts of Chinatown, and approximately 15 monks and nuns in residence. The temple’s only health activity is an annual free flu shot day (in collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene). Occasionally the temple offers free meals and conducts social welfare fund-raising events, for helping flood victims in China for example. In contrast to the other two institutions, it does not provide more general community services.

Hindu Temple

Established some 30 years ago, the Hindu temple is located in a Queens neighborhood with large numbers of immigrants from several Asian countries. It has approximately 20,000 members on its mailing list, primarily Indians living in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. With about 30 full-time staff members – including 10 priests – and several part-time staff, the temple provides a full range of religious services, plus numerous social, cultural, educational, and social service activities, including art, language, music and dance classes for children and youth, social programs for the elderly, and a cafeteria serving South Indian food. Health activities include an annual blood donation drive and an annual health fair, which offers routine health exams and information on diverse health topics including HIV/AIDS (although most of the respondents were not aware of the availability of HIV information at the health fair).

Islamic Center and Mosque

Founded 25 years ago, the Islamic Center and Mosque is located in a Queens neighborhood with a large number of South Asian immigrants and African Americans. The center is the headquarters of an Islamic nonprofit organization with 5,000 members and branches throughout the US and Canada. The center has 24 full-time staff members and houses both a social services unit and a mosque. Although the center welcomes all Muslims, most of its members are Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian. Most of its non-South Asian members (primarily African American Muslims) are clients of the social services unit, which provides temporary shelter to women, aid to people affected by discrimination following the 9/11 attacks, emergency financial assistance, and general case management services. The center offers some health education programs for clients and staff at which the issue of HIV has been raised, although these educational activities have been provided inconsistently.

Participant Characteristics

Table II provides an overview of participant characteristics, including participants’ institutional roles. To preserve the confidentiality of their comments in the Results section below, we use generic terms such as “religious respondents” to describe religious leaders, monk, and nuns; “lay respondents” to describe lay leaders, staff, and members; or “respondents” if additional description might reveal their identity.

Table II.

Participant Characteristics by Institution

| Buddhist Temple Participants |

Hindu Temple Participants |

Islamic Center/Mosque Participants |

All Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Respondents | 5 | 7 | 5 | 17 |

| Gender | 2 Female 3 Male |

2 Female 5 Male |

1 Female 4 Male |

5 Female 12 Male |

| Ethnicity/Sub-Ethnicity/State (Indians) | 5 Chinese: 2 Fujianese 1 Mongolian 1 Shanghainese 1 Taiwanese |

7 Indian: 3 Karnataka 2 Andhra Pradesh 2 Tamil Nadu |

1 African Am. 1 Bangladeshi 3 Indian: 2 Andhra Pradesh 1 Bihar |

1 African Am. 1 Bangladeshi 5 Chinese 10 Indian |

| Mean Age (SD) | 54.0 (10.9) | 52.9 (15.3) | 46.6 (10.6) | 51.4 (12.5) |

| Mean Years in U.S.a (SD) | 15.8 (12.2) | 20.0 (13.2) | 18.2 (11.1) | 18.2 (11.7) |

| Mean HIV Knowledge Scoreb (SD) | 2.6 (2.4) | 6.7 (1.6) | 5.4 (0.5) | 5.1 (2.4) |

| Role in Institution | 1 Abbot 2 Monks/Nuns 2 Members |

1 Priest 1 President 1 Vice President 1 Staff Member 3 Members |

1 Imam 1 Director 1 Staff Member 2 Members |

5 Religious Leaders 3 Lay Leaders 2 Staff Members 7 Members |

| Language of Interview | 5 Mandarin | 7 English | 4 English 1 Urdu |

5 Mandarin 11 English 1 Urdu |

All respondents were immigrants to the U.S., except for one from the Islamic Center/Mosque.

Score reported is the mean number of correct items on a 9-item true/false questionnaire. “Don’t Know” were considered to be incorrect.

RESULTS

Organizational HIV Prevention Readiness Framework

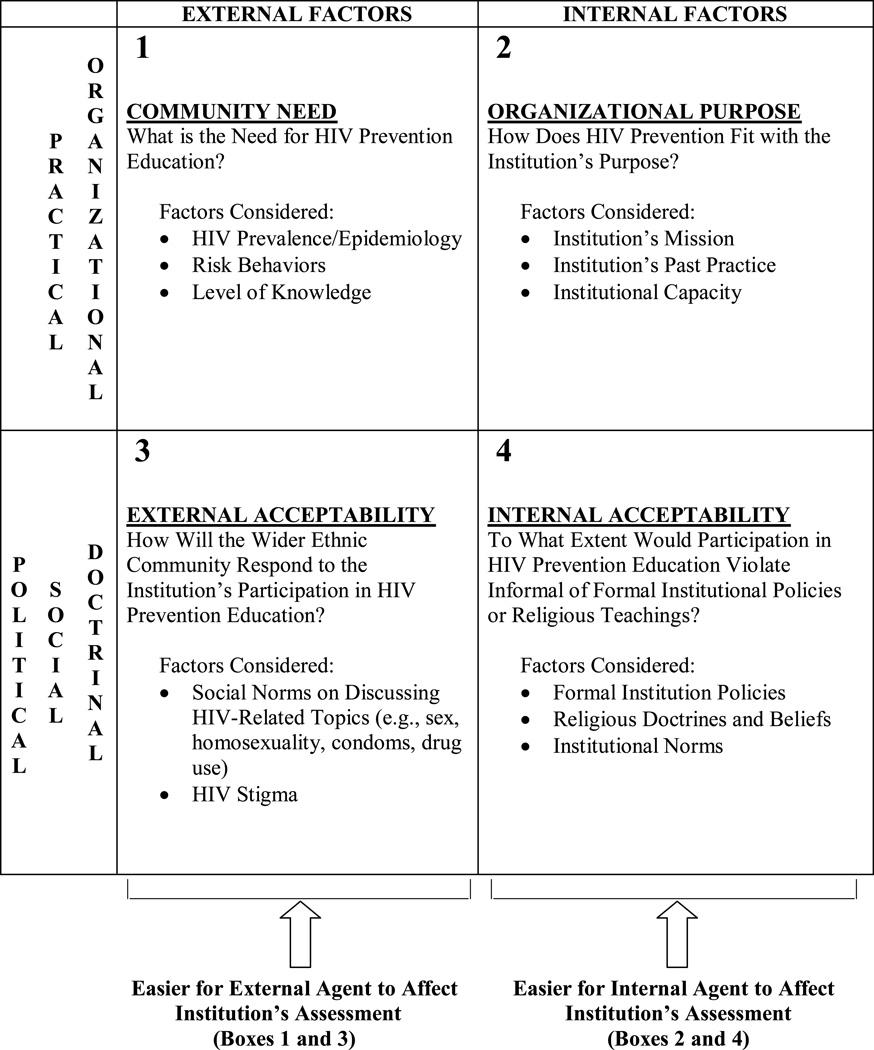

Four salient themes emerged about the factors the institutions would consider in deciding what role to play, if any, in HIV prevention. We have organized these themes into four dimensions of an organizational HIV prevention readiness framework. As shown in Figure 4, these dimensions are: (1) Community Need: What is the need for HIV prevention education? (2) Organizational Purpose: How does HIV prevention fit with the institution’s purpose? (3) External Acceptability: How will the wider ethnic community respond to the institution’s participation in HIV prevention education? and (4) Internal Acceptability: To what extent would participation violate informal or formal institutional policies or religious teachings?

Figure 4.

Organizational HIV Prevention Readiness Framework

In the left column of the model (boxes 1 and 3) are factors that are external to the institution’s core. In the right column (boxes 2 and 4) are the factors internal to the institution’s core, mainly concerning the deliberations of leaders and highly active members. The top two boxes (boxes 1 and 2) contain practical or organizational questions, while the bottom two (boxes 3 and 4) contain political, doctrinal or social concerns. Respondents demonstrated the ability to consider these areas separately but sometimes conflated them (e.g., believing there is no need for HIV education (box 1) because community members are uncomfortable discussing it (box 3)).

The dimensions of this organizational readiness framework have analogs in existing theories of organizational change, including modern stage theory of organizational change and organizational development theory. Modern stage theory, however, does not adequately address the social, political and doctrinal concerns explored here (Steckler et al., 2002). Although organizational development theory addresses these issues better with its focus on organizational climate and culture (Steckler et al., 2002), it does not address the environment outside of the organization, to which institutions in this study appear to be highly sensitive.

In the sections below, we explore in more depth respondents’ comments within each of the four dimensions of the readiness framework.

Community Need

Within and across institutions, there was wide variation in the perceived need for HIV prevention education. Overall, most respondents believed that HIV prevalence was relatively low or nonexistent in their respective communities. Many also believed that religious teachings that encouraged and prohibited certain practices (e.g., abstinence and homosexual activities, respectively) were sufficient to protect individuals from HIV infection.

At the Buddhist temple, a somewhat fatalistic religious philosophy about disease in general also might have shaped views on the need for HIV prevention education. Referring to SARS, one religious respondent explained:

Other people might look at SARS as an accidental event, but for us it’s not. We believe if you don’t have “yuanfen” [roughly, “fate,” “luck” or “destiny”] with SARS, you are just not going to get SARS. Even if you are around people with SARS, you are still not going to get infected. It’s like if you are not meant to die now, you are not going to die.

Another Buddhist temple religious respondent felt that the need for HIV education was low because people innately know about how to reduce their sexual risk of HIV.

I think in general, most people out there know how AIDS spreads around – through sexual activities. Even when I was a kid, I knew that. Most people have enough information. Without education, people should already know. For example, a person with a very low IQ still wants to get married. Why? A lot of things come naturally to people. We don’t need to be taught to learn those things. People usually know that HIV is from sexual activities, you don’t need to educate them.

Most respondents did, however feel, that some HIV prevention efforts were needed to keep prevalence low, at least in the larger ethnic community (if not within their institution itself). This was particularly true of the respondents from the Hindu and Islamic organizations. In fact, at the Islamic center, four out of the five respondents thought the need for HIV education was high. According to one respondent:

…[HIV] could become an issue if we don’t educate.… I mean we are living in a community, I mean we are part of the bigger community so we cannot isolate ourselves.

Perception of higher need at the Hindu and Islamic organizations may be a reflection of different HIV prevalence rates in the respondents’ countries of origin. India has a relatively high estimated rate of HIV prevalence (0.9%) (MAP Network, 2004). China has a large and increasing number of HIV cases (Ruxrungtham et al., 2004), but its overall prevalence is still estimated to be relatively low (0.1%) (MAP Network, 2004). A Hindu temple respondent, for example, expressed particular concern about men visiting sex workers when traveling in India and then infecting their wives in NYC:

There are men in India whom I’ve come across, and they’re very … successful businessmen, but they have no knowledge of health. They will probably run to prostitutes … Their own wives may not know.… I’m more concerned about the innocent victims, the women and children … The wives of so-called men are the ones who are victimized. So we need to educate them.

Differences in the perceived need for HIV education may have also been related to the organizations’ different age demographics. Buddhist temple members tended to be significantly older than members of the Hindu temple and Islamic center. If the Buddhist members had children, they were likely to be already grown. Interest in HIV among participants from the Hindu temple and Islamic center, may in part reflect their concern about their children, particularly given some respondents’ perception that young people in the US have too much sexual freedom.

Perception of the need for HIV prevention education might have also been related to respondents’ knowledge about HIV, especially when low knowledge meant not understanding that there were effective ways to educate people about prevention. As indicated by the mean scores on the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire, respondents’ knowledge across the three institutions varied widely (see Table II). Respondents from the Buddhist temple were least knowledgeable about HIV transmission and most concerned about getting infected through casual contact. According to one religious and one lay respondent at the Buddhist temple:

There is a possibility of getting infected when we are around [someone with HIV]. For example, we might get infected by touching anything of his/hers. There might be bacteria on it. So it’s better not to be near that person.

[Asked what the respondent would do if a person with HIV moved in next door] What could we do? (Laughter) I think it’s better not to be near this person. We would have to move, I guess. We couldn’t ask him to move.

This low level of knowledge may reflect their limited English language skills (and consequent lack of exposure to English media and educational materials), as well as the isolation from worldly matters of three of the five respondents who were living monastically.

The respondents from the Hindu temple and the Islamic center tended to be more knowledgeable about HIV transmission and were more likely to have had some formal education about HIV through schooling or workshops; none expressed fear about casual contact with someone with HIV. Still, one lay respondent at the Hindu temple believed that HIV can be transmitted by drinking from the same glass, and a respondent at the Islamic center believed that HIV could be transmitted by sharing a bar of soap with an infected person. Surprisingly, despite the belief that HIV can be transmitted easily, the Islamic center respondent expressed little fear of becoming infected through casual contact with a person with HIV because he perceived the disease to be less dangerous now due to the availability of new treatments.

Organizational Purpose

Regarding organizational purpose, lay respondents (i.e., active members, organization officers, staff) tended to see a better fit between organizational purpose and engagement in HIV-related activities than religious respondents (i.e., abbots, imams, priests, monks and nuns). Still, while religious respondents generally felt that the primary focus of organization activities should remain on religious teaching and activities, they also felt that other types of community service had a place in the organizations’ work.

Sometimes respondents provided contradictory assessments, possibly due to HIV stigma. At the Buddhist temple, while religious leaders said that HIV-related work might fall outside of the temple’s mission because it was not related to providing religious teaching, they endorsed non-HIV health-related activities (i.e., an annual flu shot day) and fund-raising for charitable causes (i.e., for flood victims in China) – activities they perceived to be fully consistent with the temple’s purpose. This apparent contradiction might also arise from the religious leaders’ belief that discussion of HIV-related topics (e.g., sex and drug use) would be inappropriate in a temple.

At the Hindu temple, almost all of the lay leaders and active members felt that there was a good fit between the temple’s basic purpose and providing or supporting HIV education. A religious respondent was the only person who thought the fit was poor.

See, this is a religious place. Yes, as you say, if we have to teach them [about HIV], we have to tell them all these things [sexuality, homosexuality, prostitution, drug use, condoms] here. I don’t think it’s the right place for that here. In the hospital, they don’t say about religion, so just like that, they don’t have to say much about [HIV] in the temple. If anybody particularly comes and asks [about HIV], … we can guide them or help them. Otherwise I don’t think we need that here.

Consistent with the findings from the Buddhist temple, the Hindu temple religious respondent’s disapproval of involvement in HIV education contradicted his endorsement of the temple’s role in promoting the general health and welfare of temple members. Most of the Hindu temple respondents expressed similar contradictions although to a far lesser degree.

In contrast, the respondents at the mosque, which provides health information, clearly saw the link between their health-related work and HIV-related activities. A religious leader stated succinctly, “See, overall, when an organization starts a health service and provides health information, HIV will also be a part of that.”

External Acceptability

When asked to consider whether the organization might sponsor or support an HIV-related activity, respondents often commented about the possible response of the larger institutional membership and the wider ethnic community. All expressed concern about lack of community acceptance, either in terms of low attendance at HIV-related events because of HIV stigma or negative impact on the organization’s image. Two religious respondents (both celibate) from the Buddhist temple held the more extreme views about this.

…Our presence at such events might arouse some public resentment. We might become the laughing stock.

Doing such things [engaging in HIV-related activities] might pose some negative impact on our image.… We would be supportive [of HIV-related activities] under the premise that it wouldn’t affect our image.… if the impact [on our image] is small, I would support it. But if the impact is big, then I wouldn’t.

At the Hindu temple, a lay respondent felt that low attendance at HIV-related events would be a problem, not just because it would mean the event was unsuccessful, but also because low attendance would make members who did attend feel exposed: “… you don’t want to say yes, please conduct it and then hardly anybody shows up, and it doesn’t look nice [for] the organizers or … [for] the few people that come.”

Another Hindu temple respondent felt that the community’s concerns about the temple’s involvement in HIV-related issues would be related to the kinds of issues associated with HIV, such as sex, homosexuality, and prostitution: “Homosexuality is one thing which Indian people are like, they know it, they know those kind of things, but they don’t want to accept it, you know. Truth is always bitter, okay? So they don’t want to take that bitterness. And to make them understand that bitterness is very difficult.”

The respondents at the Islamic center also felt community members, particularly the older ones, might be uncomfortable hearing about HIV. However, rather than seeing this as a deterrent to being involved in HIV education, they felt it reflected the need to raise HIV awareness.

Internal Acceptability

In considering their organizations’ readiness to engage in HIV prevention activities, respondents also discussed concerns regarding “internal acceptability” – consistency with the organization’s religious teachings and organizational culture. Respondents at the Buddhist and Hindu temples expressed concerns about the appropriateness of discussing HIV-related topics in a religious setting, as noted earlier. A Buddhist religious leader explained, “as Buddhists, we don’t like to talk about obscene subjects. There is no need for us to talk about these things.” Even if the need for HIV education could be justified, he still felt that the temple’s involvement could lead members down the pathway to sin, interestingly, not by encouraging them to engage in sexual or drug-using behaviors, but by allowing them to disparage the monks and nuns who participated in the educational event and thereby commit an “oral sin”:

As Buddhists, we shouldn’t appear in inappropriate occasions. Audiences will look at us with tainted glasses and say things like “what kind of monks would show up here?” They might even call us “obscene monks.” By calling us names, they would commit oral sins.

As Buddhists, we shouldn’t do anything that might lead someone to commit any kind of sin. According to the law of “causes and consequences” anyone who commits oral sins would have to suffer in hell.

Buddhist temple lay respondents felt that it would be acceptable to discuss HIV prevention if it were for educational purposes: “They wouldn’t like to discuss obscene or dirty subjects here. But if those subjects are discussed for education, if you discuss them in a scientific way, then I don’t think it would matter. I think the Abbot would not mind either.”

At the Hindu temple, there was little concern about violation of core temple policies or religious teachings, although some respondents felt that some of the leadership might be resistant to involvement in HIV on religious grounds. However, because the HIV education would take place in one of the temple’s cultural halls, one lay respondent felt that concern about violation of temple policies or teachings would be minimized. This respondent also reasoned that discussion of HIV-related issues such as homosexuality would not violate the sanctity of the temple since such issues are already discussed in religious texts.

In contrast to the Buddhist and Hindu temple respondents, lay and religious leaders at the mosque focused less on the appropriateness of addressing HIV prevention in religious settings and more on the content of prevention messages, emphasizing that they must be consistent with religious prohibitions, particularly regarding homosexuality and non-marital sex. For example, one lay respondent commented:

… in promoting education we don’t have any problem, but on certain issues we may say no.… Our slogan will be no.… I mean we will say that [sex] only is allowed [within] the family structure, with a husband and wife; otherwise it’s no.… We will educate that if you go other way, then you may have these problems and if you have these problems then your health is at risk. This kind of education we are always [supporting].… Yes we can [discuss homosexuality] and we can tell them that this is “no” as a religious [matter]. It is totally forbidden.… That this is wrong.

DISCUSSION

Study participants’ assessments were rich with tensions, contradictions, rationalizations and uncertainties at many levels, largely rooted in the fact that HIV is highly stigmatized and that discussion of HIV entails consideration of taboo subjects like homosexuality and drug use. Some leaders expressed concerns about the institution’s image and the potential for the institution to be stigmatized for discussing and implicitly condoning stigmatized behaviors like non-marital sex. In addition, even when participants felt that addressing these HIV-related taboo topics would be acceptable in general, they were often unsure about the appropriateness of discussing them in a religious setting.

There were differences of opinion between religious leaders and lay leaders or members. Religious leaders were less likely to see a need for HIV education and more hesitant to acknowledge that the institution should play a role in HIV-related efforts. (It should be noted that at the Hindu temple and the Islamic center, the lay leadership had more authority over most institutional decisions than the religious leadership.) Often, a respondent would give opposing assessments of the different dimensions in the readiness framework described previously (Figure 4). For example, respondents often saw a need for HIV prevention education (box 1, “Community Need”) but low acceptability (box 3, “External Acceptability” and box 4, “Internal Acceptability”). In some cases, the assessment of one dimension in the readiness framework affected the assessment of other dimensions. For example, respondents’ assessment of whether involvement in HIV prevention would fit the institution’s purpose (box 2 in Figure 4) was sometimes colored by their assessment of community acceptance of HIV as a suitable discussion topic (box 3). Respondents also expressed contradictions within dimensions, for example, establishing a double-standard around HIV by describing involvement in a “flu shot” day as fully consistent with the organization’s purpose but seeing involvement in HIV as a violation of the organization’s purpose because it is not a religious activity.

A fundamental tension was rooted in the conflict participants perceived between morality and compassion. Although HIV is highly stigmatized and an issue that the religious institutions seemed hesitant to embrace, the institutions’ leaders and members also valued community service, public health promotion, and compassion towards those in need as taught by their religions. Analysis of participants’ comments indicate that when faced with the tension between morality and compassion that is created by a new issue like HIV, institutions undergo a self-assessment process (along the lines of the dimensions in Figure 4) that leads to what one might call “conservative innovation.” That is, institutional leaders and members, when confronted with a new situation or need, interpret how their religious teachings, cultural values, and institutional policies could apply to the changing, everyday lives of their members and then adjust their practices or positions incrementally to stay responsive and relevant. This stance of “conservative innovation” arises from the tension between respondents’ wish to maintain a certain morality and tradition (the “conservative” impulse) and their wish to serve their constituents effectively as they face new challenges (the “innovative” impulse). The oxymoronic phrase “conservative innovation” is chosen deliberately to describe this process because it embodies the tension that some institutions might sustain without ever fully resolving.

The stance of “conservative innovation” may be more pronounced in religious organizations in immigrant communities than in their counterparts in their countries of origin. Religious organizations in immigrant communities may feel a greater responsibility to care for community members since immigrants are more likely to turn to these organizations for a wider range of information and services than they would in their home countries. Establishing that there is an urgent need for HIV education and providing some reassurance about community acceptance may help to prompt religious organizations’ involvement in HIV-related activities.

Areas of contradiction and tension provide opportunities for introducing HIV-related activities in these settings, largely because respondents seem to take their roles as community caretakers so seriously. For example, raising leaders’ awareness about an institutional double-standard around HIV might help open up involvement in HIV-related activities, or at least productive dialogue about it. But there is a flip-side to this dynamic in that organizations that express little contradiction or tension may hold the most rigid positions and be least likely to change. For example, there was little disagreement between the lay and religious leadership at the Islamic center. In addition, they did not express the same double-standard regarding the inclusion of HIV-related activities within the organization’s community service work. They were also quite progressive in their understanding that HIV prevention education might prevent an epidemic. But this institution was the least flexible in its approach to HIV education, being adamant that HIV prevention messages should emphasize that homosexual and non-martial sex are “forbidden.” In this case, change might be encouraged if new information creates tension or contradiction. For example, hypothetically, if new information indicated that the most effective methods of HIV prevention education included non-judgmental discussion of homosexuality and non-martial sex, it might create enough tension between the wish to meet community needs and the wish to maintain tradition to stimulate change in the organization’s approach to HIV education, activating the “innovation” side of the “conservative innovation” stance.

Implications for Organization-Level Intervention

The religious institutions’ stance of “conservative innovation” provides opportunities for an outside organization (e.g., health department, social service agency) to work effectively with the institutions by engaging with their readiness assessment processes (as shown in Figure 4). Although respondents did not fully embrace HIV education, they demonstrated a willingness to consider its role in their religious institutions. In fact, almost all agreed that it is appropriate and important for the institutions to play a role in promoting health in the community, even if they were reluctant to take on HIV specifically. With the exception of the Buddhist temple, no respondents indicated that formal policies or religious teachings prohibited religious institutions’ involvement in HIV educational activities. However, it is important to note that the mosque reported that religious teachings would constrain the content of prevention messages to the extent that they may conflict with public health interests, particularly with regard to prevention initiatives for men who have sex with men and individuals engaged in non-marital sex.

Our organizational readiness model suggests strategic points for intervention. The most strategic points for an external agent to impact an institution’s readiness assessment would be the external factors on the left side of the model (boxes 1 and 3). Perhaps the most straightforward area of intervention would be box 1 (“what is the need for HIV education”). This would entail providing education to institutional leaders and members about HIV prevalence in the ethnic community, why the community might be at risk, and the benefits of providing prevention education before more people get infected. In addition, research could be conducted and findings presented on the actual level of HIV knowledge and risk behaviors among community members. Many respondents simply assumed that community members had high levels of knowledge and low levels of risk behavior.

Intervening in box 3 (“how will community members respond?”) is more difficult. Possible interventions here might be community-wide anti-stigma or awareness campaigns. For example, use of media – ethnic cable television, ethnic press, and mass transportation advertising – might create a context of awareness and positive community-wide attitudes about HIV that might help to garner institutional support for subsequent HIV prevention activities.

Attempting to intervene in the right side of the model (boxes 2 and 4) might be seen as intrusive or offensive by the institution. For example, because the Islamic center was already firmly convinced that HIV education is needed in the community (box 1) and had formulated a firm stance on the appropriate content for HIV education (box 4), there might be little opportunity for impacting its overall assessment process. Doing so would require a change in views on religious teachings. It might be possible, however, to work with internal change agents who might be able to impact the institution’s assessment of its purpose (box 2) and interpretations of religious teachings (box 4). These change agents might come in the form of “natural helpers” (Eng and Parker, 2002) or “opinion leaders” (Kelly et al., 1991; 1992). Providing peer education training to natural helpers, to whom others naturally turn to for advice and support, also may provide a way of implementing an HIV prevention intervention within an institution where a less visible and more private approach would be more appropriate.

CONCLUSION

Asian immigrants need HIV education to prevent transmission in their communities and to assist community members who are already infected. Working with immigrant institutions is an important part of this work, and of all immigrant institutions, religious institutions may be particularly important. To work with these institutions effectively, we need to understand their attitudes about HIV involvement and their perception of the risk HIV poses for the communities they serve. This article, which reports on the first systematic study of Asian immigrant religious institutions and HIV prevention in the US, begins to serve that purpose. Our study findings suggest possible strategic intervention points for affecting these institutions’ assessment of whether and how to be involved in HIV prevention education.

This is an exploratory study designed to surface complex institutional dynamics surrounding HIV prevention. The data presented in this article were intended as a first step to describe a relatively unknown area. Because this article includes only three of the many Chinese and South Asian religious institutions in NYC, its findings are not necessarily generalizable to other Asian religious institutions. Moreover, we studied a small convenience sample of mostly leaders and active members within each institution, so their views are more likely to be typical of the leadership rather than the general membership. Although each institution has been characterized by its religious affiliation, these institutions are not necessarily representative of other institutions of the same faith. An important next step will be to test and refine the model described here on a larger sample and to determine whether the model, in whole or in part, is relevant to other types of institutions. Future analyses will examine the similarities and differences across institution types and populations.

This research also raises the issue of what types of HIV prevention activities immigrant institutions should pursue – another area for future study. Religious institutions, for example, could sensitize their members about AIDS, promote community norms for HIV prevention and reduction of stigma, provide spiritual guidance around HIV/AIDS, incorporate HIV/AIDS prevention efforts into ongoing program activities, and mobilize other institutions to become involved in HIV/AIDS activities. Although a number of respondents, including institution leaders, supported the idea of taking an active role in HIV prevention, the data also suggest that some religious institutions may not be able to carry out direct HIV prevention activities effectively. Instead, these institutions might be more useful in increasing basic HIV awareness through charitable or other activities that are more consistent with their institutional missions and religious teachings. Social norms concerning appropriate topics of discussion may be particularly prevalent and potent as barriers to HIV education in immigrant communities, and thus, religious institutions’ involvement in raising general awareness about HIV and changing norms about the appropriateness of discussing it may be a vitally important first step that will allow subsequent direct HIV prevention efforts in these communities to be more effective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research for this article was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant Number 1 R21 HD43012-02). The authors would like to thank Peggy Dolcini at the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. The authors would also like to thank the agencies who served on the study’s advisory committee: Asian and Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS, Chinese-American Planning Council HIV/AIDS Services, Sakhi for South Asian Women, and South Asian Health Project. Special thanks also go to Yingfeng Wu for creating the maps of Asian immigrant religious institutions. Finally, we deeply appreciate the willingness of the religious institutions, and their leaders and members, to participate in this study and share their views with us.

Footnotes

A search of PubMed revealed no studies of HIV-related community-level interventions targeted to Asians in the US, and only 3 community-level interventions addressing other health issues for Asian Americans.

In the case of the Hindu temple, we interviewed seven respondents. This was because the leadership was eager for us to interview a number of individuals and it would have jeopardized our relationship with the temple to refuse.

REFERENCES

- AAFNY. New York City Asian American Census Brief. New York: Asian American Federation of New York Census Information Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- AIDS Action. Policy brief: Faith-based response to HIV/AIDS. Washington, D.C.: AIDS Action; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal. 2001 May;322(5):1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch L, Glick Schiller N, Szanton Blanc C. Nations unbound: transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. US HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 2001, year-end edition. no. 2. vol. 13. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, 2002. vol. 14. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance supplemental report. Cases of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States, by Race/Ethnicity, 1998–2002. no. 1. vol. 10. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chin D, Kroesen KW. Disclosure of HIV infection among Asian/Pacific Islander American women: Cultural stigma and social support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 1999;5(3):222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Coates TJ, Catania JA, Lew S, Chow P. High HIV risk among gay Asian and Pacific Islander men in San Francisco. AIDS. 1995;9(3):306–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. Coding, writing memos, and diagramming. In: Swanson JM, editor. From Practice to Grounded Theory: Qualitative Research in Nursing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Eckholdt HM, Chin JJ, Manzon-Santos JA, Kim DD. The needs of Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV in New York City. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1997;9(6):493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Parker E. Natural Helper Models to Enhance a Community's Health and Competence. In: Kegler MC, editor. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Rapkin B, Kim J, Springer C, Chhabra R. Voices: An assessment of needs among Asian and Pacific Islander undocumented non-citizens living with HIV disease in New York City. New York: Mayor's Office of AIDS Policy Coordination and the New York HIV Health and Human Services Planning Council; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA. Community-level interventions are needed to prevent new HIV infections. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(3):299–301. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, Kalichman SC, Smith JE, Andrew ME. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. [see comments] American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(2):168–171. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Kalichman SC, Diaz YE, Brasfield TL, Koob JJ, Morgan MG. Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: the effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. [see comments] American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(11):1483–1489. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I. The Koreans: small business in an urban frontier. In: Foner N, editor. New Immigrants in New York. New York: Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Loue S, Lane SD, Lloyd LS, Loh L. Integrating Buddhism and HIV prevention in U.S. southeast Asian communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999;10(1):100–121. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- MAP Network. AIDS in Asia: face the facts. Washington, DC: Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic (MAP) Network; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Min PG. Introduction. In: Kim JH, editor. Religions in Asian America: Building Faith Communities. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NYCDOH. Unpublished Data. New York: New York City Department of Health, HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- NYCDOH. Surveillance update, including persons living with AIDS in New York City, reported through 12/2001. New York: New York City Department of Health, HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NYCDOHMH. HIV surveillance and epidemiology program, 3rd quarter report. no. 3. vol. 1. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance and Epidemiology Program; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- NYCDOHMH. HIV surveillance and epidemiology program, 3rd quarter report. no. 3. vol. 2. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, HIV Surveillance and Epidemiology Program; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxrungtham K, Brown T, Phanuphak P. HIV/AIDS in Asia. Lancet. 2004;364(9428):69–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16593-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler A, Goodman RM, Kegler MC. Mobilizing Organizations for Health Enhancement: Theories of Organizational Change. In: Lewis FM, editor. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sy FS, Chng CL, Choi ST, Wong FY. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1998;10(3) Suppl:4–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Wilson P, Hsueh J, Rosman EA, Chin J, Kim JH. What front-line NGO staff can tell us about culturally anchored theories of change in HIV prevention for Asian/Pacific Islanders in the U.S. 2001 doi: 10.1023/a:1025611327030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka MR, Schustack A. Disclosure of HIV status: cultural issues of Asian patients. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2001;15(2):77–82. doi: 10.1089/108729101300003672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Chinatown: the socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]