Abstract

Physiological oxidants that are generated by activated phagocytes comprise the main source of oxidative stress during inflammation1,2. Oxidants such as taurine chloramine (TnCl) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) can damage proteins and induce apoptosis, but the role of specific protein oxidation in this process has not been defined. We found that the actin-binding protein cofilin is a key target of oxidation. When oxidation of this single regulatory protein is prevented, oxidant-induced apoptosis is inhibited. Oxidation of cofilin causes it to lose its affinity for actin and to translocate to the mitochondria, where it induces swelling and cytochrome c release by mediating opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP). This occurs independently of Bax activation and requires both oxidation of cofilin Cys residues and dephosphorylation at Ser 3. Knockdown of endogenous cofilin using targeted siRNA inhibits oxidant-induced apoptosis, which is restored by re-expression of wild-type cofilin but not by cofilin containing Cys to Ala mutations. Exposure of cofilin to TnCl results in intramolecular disulphide bonding and oxidation of Met residues to Met sulphoxide, but only Cys oxidation causes cofilin to induce mitochondrial damage.

Control of the cellular oxidation-reduction (redox) environment is essential for normal physiological function3,4. Oxidants have the capacity to induce cellular damage and death through a variety of mechanisms depending on the nature of the oxidant and the environment in which it is formed5,6. Oxidants such as H2O2 and HOCl can cause damage to proteins7–9, lipids and DNA, resulting in diverse functional outcomes10. TnCl, the main oxidant generated by activated neutrophils, has a limited spectrum of reactivity, with primary targets being Cys and Met residues of proteins11,12. Previous studies showed that TnCl causes apoptosis through damage to the mitochondria6, resulting in decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and non-physiological swelling13,14.

The goal of this research was to identify proteins that are modified during oxidant-induced apoptosis and to determine which of these are responsible for causing apoptotic cell death. We took advantage of the fact that TnCl causes cells to die almost exclusively through apoptosis5,6 and hypothesized that TnCl induces apoptosis by causing oxidation of Cys and/or Met residues in specific proteins. Due the unique reactivity of Cys sulphydryls with iodoacetamide, the change in the redox status of Cys residues can be detected by labelling with fluorescein-conjugated iodoacetamide15,16 (5-iodoacetamidofluorescein, 5-IAF). Using redoxproteomics, we discovered 21 Cys-containing proteins that are oxidized within 1 h of TnCl treatment (Supplementary Information, Figs S1 and S2). Apoptosis is observed several hours later.

To assess which of the proteins oxidized by TnCl have a role in mediating apoptosis, we focused on proteins that participate in mitochondrial apoptosis. Cofilin-1 was identified as a particularly interesting candidate17. It controls all functions of actin. Previous studies showed that cofilin mediates apoptosis in response to staurosporine18, VP-16 (ref. 18) and TGF-β19 through its translocation to the mitochondria, and that it regulates apoptotic morphology20. Regulation of apoptosis and mitochondrial integrity through oxidation of cofilin has not been reported.

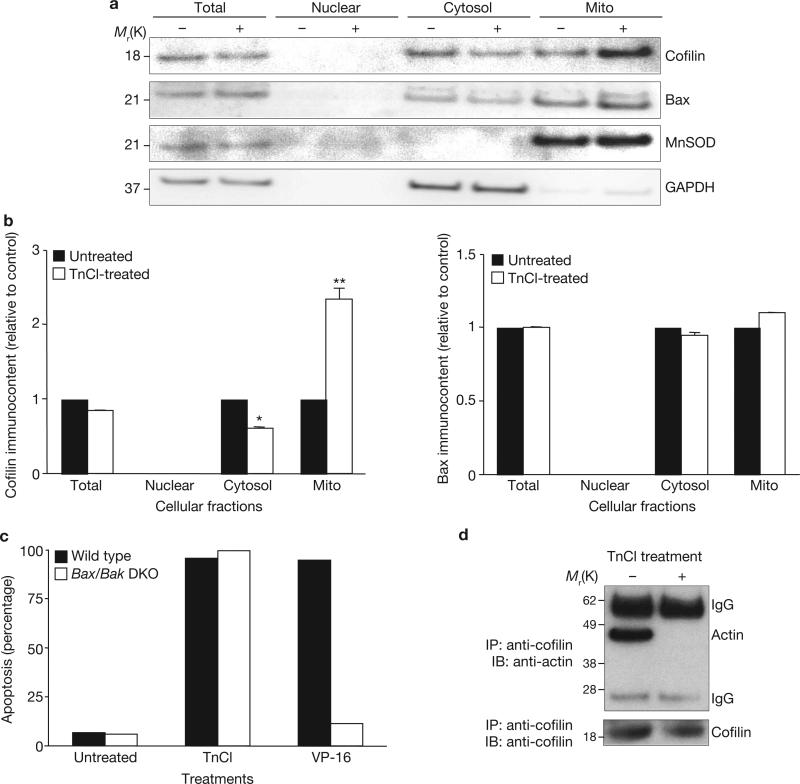

TnCl treatment caused translocation of cofilin from the cytosol to the mitochondria (Fig. 1a, b). This change in the subcellular localization of cofilin was detectable within 1 h, concurrent with a measurable decrease in Δψm6. The following studies examined whether apoptosis caused by TnCl is due to a direct effect of oxidized cofilin on the mitochondria or whether it is mediated by activation of the Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bak, which are known to cause permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane and release of cytochrome c21,22. A possible role for Bax in TnCl-induced apoptosis was ruled out by several observations. First, for Bax to mediate apoptosis, it must translocate to the mitochondrial outer membrane and undergo a conformational change and oligomerization23. No Bax translocation to the mitochondria was found after TnCl treatment of cells (Fig. 1a). Second, these studies used a monoclonal antibody that only recognizes activated Bax (epitope 6A7). Western blot data showed no change in the apparent levels of Bax after induction of apoptosis by TnCl, indicating that Bax does not undergo conformational activation in response to TnCl. Third, there was no difference in the levels of apoptosis induced by TnCl in mouse embryonic fibroblasts that were deficient in both Bax and Bak24, compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 1c). In contrast, induction of apoptosis by VP-16 was almost completely prevented in the Bax/Bak-knockout cells.

Figure 1.

TnCl causes dissociation of actin/cofilin complexes and translocation of cofilin to the mitochondria independently of Bax activation. (a) Subcellular fractionation was carried out on control (–) or TnCl-treated (+) JLP-119 lymphoma cells (0.5 mM TnCl in PBS for 1 h) before analysis by a western blot immunoassay using anti-cofilin, anti-Bax, anti-MnSOD (mitochondrial isoform of superoxide dismutase) or anti-GAPDH (as a cytosolic marker) as described in the Methods. (b) Densitometric analysis of cofilin (left panel) or Bax (right panel) bands in the different subcellular compartments shown in a. Bands from treated cells were normalized to each respective control band and to the internal controls from untreated cells. Data are mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments; *P < 0.005 compared with control, **P < 0.001 compared with control (Student's t-test). (c) Wild-type or Bax–/–/Bak–/– double knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts were treated with TnCl (1.5 mM) or VP-16 (100 μM) in complete media for 1 h, after which the medium was replaced. Cell death was evaluated 24 h later by flow cytometry after staining with annexin-V/FITC and propidium iodide. The data are the means from two independent experiments. (d) JLP-119 lymphoma cells were treated with TnCl (0.5 mM) in PBS for 1 h and then cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-cofilin antibody as described in the Methods. Western blot immunoassay (IB) used either anti-actin or anti- cofilin, as indicated in the figure. Mito, mitochondria. See Supplementary Information, Fig. S8 for full scans of a and d.

As cofilin functions as an actin regulatory protein, we investigated whether the oxidation of cofilin affects actin binding, and found that it does. Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates with an anti-cofilin monoclonal antibody revealed that, as expected, actin co-precipitated with cofilin in healthy, untreated cells. However, this actin–cofilin complex was lost after TnCl exposure (Fig. 1d).

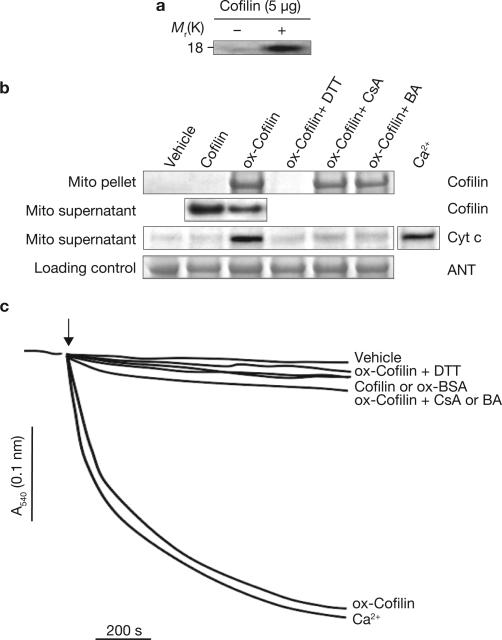

If oxidation and mitochondrial translocation of cofilin mediate apoptosis in response to TnCl, then there should be a direct effect of oxidized cofilin on the integrity of the mitochondria. This possibility was investigated by measuring two features of mitochondria-driven apoptosis: the induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition, and the release of cytochrome c13,14. Operationally, the permeability transition refers to the depolarization and swelling of the mitochondria that occurs under stress conditions, most notably as a result of calcium overload or oxidative stress25. Purified recombinant cofilin was oxidized with TnCl in vitro and was then added to isolated rat liver mitochondria. Oxidation of cofilin in vitro was confirmed by reducing and labelling cofilin disulphides with 5-IAF and detecting the labelled protein after SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2a). When oxidized and native cofilin were incubated with purified mitochondria in vitro, only the oxidized form bound to and co-precipitated with the mitochondria (Fig. 2b). This binding was accompanied by depletion of cofilin from the medium and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. Exposure of isolated mitochondria to oxidized cofilin also resulted in mitochondrial swelling comparable to that seen from exposure to excess Ca2+ (Fig. 2c). Wild-type cofilin or oxidized bovine serum albumin had a minimal effect on the mitochondria. Together, these results suggest that, when oxidized by TnCl, cofilin loses its affinity for actin, translocates to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis-related mitochondrial damage.

Figure 2.

Oxidized cofilin binds to mitochondria, causing their swelling and cytochrome c release through opening of the PTP. (a) Recombinant human cofilin was oxidized by TnCl in vitro as described in the Methods. The figure shows detection of cofilin disulphides by 5-IAF-labelling and SDS–PAGE (fluorescein fluorescent band). (b) Rat liver mitochondria were exposed to purified, recombinant cofilin (5 μg for 10 min at 37 °C) that was either untreated or previously oxidized (ox-cofilin) with TnCl (100 μM). Mitochondria were treated in the presence or absence of the mitochondrial PTP inhibitors cyclosporine A (CsA; 2 μM) or bongkrekic acid (BA; 50 μM). A sample of ox-cofilin was treated with the sulphydryl reducing agent DTT and then dialysed before adding to the mitochondria to assess the role of cofilin disulphide bonds on its biological activity. The vehicle control contained TnCl (2 μM), which has no direct effect on the mitochondria6. Cofilin protein in the mitochondrial (Mito) pellet and cytochrome c in the supernatant were assessed by a western blot immunoassay (30 μg protein per lane). Adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) was used as a loading control for the mitochondrial pellet fraction. The remaining unbound cofilin and the cytochrome c (Cyt c) released by Ca2+ treatment (150 μM CaCl2) were assessed in the mitochondrial supernatants. (c) Swelling of mitochondria exposed to native or oxidized cofilin, or oxidized bovine serum albumin (ox-BSA; 5 μg) was measured as described in the Methods. Ca2+ (150 μM CaCl2) was used as a positive control for induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition. DTT and CsA or BA treatments were as described in b. Control (vehicle) mitochondria were stable and showed no swelling under the same incubation conditions. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Previous studies showed that TnCl-induced apoptosis requires opening of the PTP; apoptosis was inhibited by bongkrekic acid6, which blocks pore opening. To determine whether oxidized cofilin causes swelling through a direct effect on the PTP, we tested the effects of bongkrekic acid and cyclosporine A and found that both blocking agents inhibited the ability of oxidized cofilin to induce the release of cytochrome c and to cause mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 2b, c). Interestingly, these compounds did not interfere with the binding of oxidized cofilin to the mitochondria.

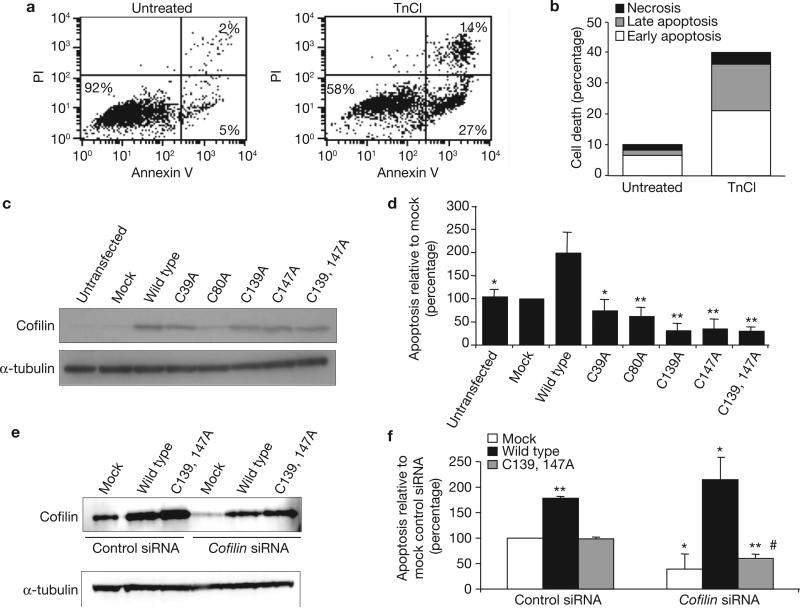

Human cofilin contains four Cys residues, at positions 39, 80, 139 and 147. To evaluate whether oxidation of one or several of these Cys residues mediates TnCl-induced apoptosis, we synthesized five expression plasmids containing human cofilin genes that were mutated to convert each Cys to an Ala residue, and one double mutant in which both Cys 139 and Cys 147 were mutated to Ala. These plasmids were transfected and overexpressed in cells to study their effects on the ability of TnCl to induce apoptosis. COS-7 cells were used because of their capacity to undergo apoptosis after TnCl treatment (41% cell death at 24 h; Fig. 3a, b), and because they express high levels of cofilin after transient transfection (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

TnCl-induced apoptosis is dependent on oxidation of Cys residues in cofilin, as determined by site-directed mutagenesis and siRNA silencing. (a, b) Induction of apoptosis in COS-7 cells 24 h after treatment with TnCl as assessed by (a) flow cytometry and (b) nuclear morphology (see Methods). PI, propidium iodide.(c) Western blot immunoassay of cofilin levels in total cell lysates from COS-7 cells transfected with plasmids expressing wild-type cofilin or cofilin in which the indicated Cys residues were mutated to Ala residues. α-tubulin protein levels served as an internal loading control. The blot shown is representative of three independent experiments. (d) At 24 h after transfection, COS-7 cells were treated with TnCl for 1 h and then the medium was replaced. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry 24 h later and is calculated relative to the levels in mock-transfected cells (lipofectamine plus empty plasmid vector). Data are mean ± s.d. from at least three independent experiments, n = 4, *P ≤ 0.01, **P ≤ 0.001 (compared to wild-type TnCl-treated cells; Student's t-test). Knockdown of endogenous cofilin with siRNA. COS-7 cells were treated with either control siRNA or cofilin siRNA as described in the Methods. After a 48 h incubation, the cells were transfected with an expression plasmid containing either no insert (Mock), the wild-type cofilin gene, or cofilin in which Cys 139 and 147 were mutated to Ala residues (Cys 139, 147). (e) Representative western blot for cofilin protein levels following knockdown and re-expression. (f) A day after transfection, the cells were treated for 1 h with TnCl (1.5 mM) and then washed. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry 24 h after TnCl treatment and is calculated relative to the levels in control siRNA, mock transfected cells. Data are mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments, *P ≤ 0.01, **P ≤ 0.001 (compared to control siRNA, mock transfected TnCl-treated cells; Student's t-test). There was no significant difference between the levels of TnCl- induced apoptosis in cofilin-knockdown cells transfected with mock plasmid versus plasmid expressing Cys-Ala mutated cofilin (#). Conditions for cofilin silencing are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S3. See Supplementary Information, Fig. S8 for full scans of c and e.

Mutation of any of the Cys residues or both Cys 139 and Cys 147 abolished the ability of TnCl to induce apoptosis, compared with cells overexpressing wild-type cofilin (Fig. 3d). The latter showed a 2.2-fold increase in apoptosis in response to TnCl treatment, compared with untransfected cells. COS-7 cells overexpressing wild-type or mutant forms of cofilin had normal morphology and no increase in basal levels of apoptosis when compared with vector-control cells 48 h after transfection. Thus, oxidation of every Cys residue in cofilin in response to TnCl is required for cofilin to take on a pro-apoptotic function.

The essential role of cofilin oxidation in mediating apoptosis was verified using siRNA to knockdown endogenous cofilin and then testing whether re-expression of cofilin lacking oxidizable Cys residues at positions 139 and 147 could replace endogenous cofilin in mediating TnCl-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3e, f). The conditions for optimizing the knockdown and re-expression of cofilin were established using different concentrations of siRNA and different time points after siRNA transfection (see Methods and Supplementary Information, Fig. S3). Knockdown of endogenous cofilin by ~70–90% resulted in significantly decreased apoptosis in response to TnCl, compared with cells treated with non-specific siRNA. Re-expression of wild-type but not mutated cofilin in the knockdown cells restored the ability of cofilin to stimulate apoptosis in response to TnCl. (Fig. 3f).

The stress-response protein HSP60 was also oxidized at Cys residues in cells exposed to TnCl (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1). However, in contrast to cofilin, overexpression of wild-type HSP60 did not enhance apoptosis in response to TnCl and expression of HSP60 lacking any oxidizable Cys residues did not interfere with induction of apoptosis by TnCl (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4). This result emphasizes the importance of determining whether an oxidation event has a causative, rather than a bystander, role in a cell regulatory pathway.

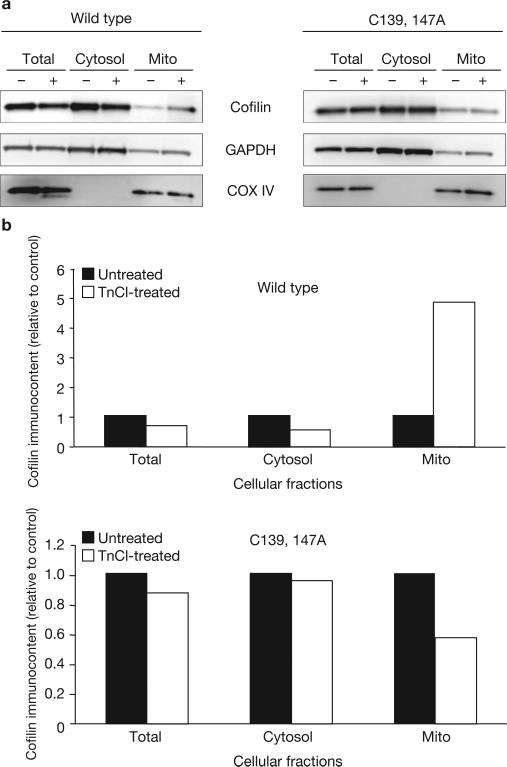

Consistent with a requirement for cofilin oxidation in the induction of mitochondrial damage during oxidant-induced apoptosis, oxidation of cofilin Cys residues is required for translocation of cofilin from the cytosol to the mitochondria. This was demonstrated by overexpressing cofilin in which Cys 139 and Cys 147 were mutated to Ala, exposing cells to TnCl and then measuring the subcellular localization of cofilin. Only wild-type (fully oxidizable) cofilin increased in the mitochondrial fraction after TnCl treatment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Oxidation of cofilin is required for its translocation to the mitochondria. (a) COS-7 cells were transfected with expression plasmids containing wild-type cofilin (left) or cofilin with Cys to Ala mutations at residues 139 and 147 (C139, 147A; right). At 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with TnCl (1.5 mM) for 3 h in complete medium, washed, collected and lysed as described in the Methods. Subcellular fractionation was carried out on control (–) or TnCl-treated (+) cells before analysis by a western blot immunoassay using anti-cofilin, anti-COX IV (as a mitochondrial marker) or anti-GAPDH (as a cytosolic marker). (b) Densitometric analysis of cofilin bands in the different subcellular compartments shown in a. Data are normalized to the relative densities of the appropriate marker bands for each subcellular fraction. Mito, mitochondria. See Supplementary Information, Fig. S8 for full scan of a.

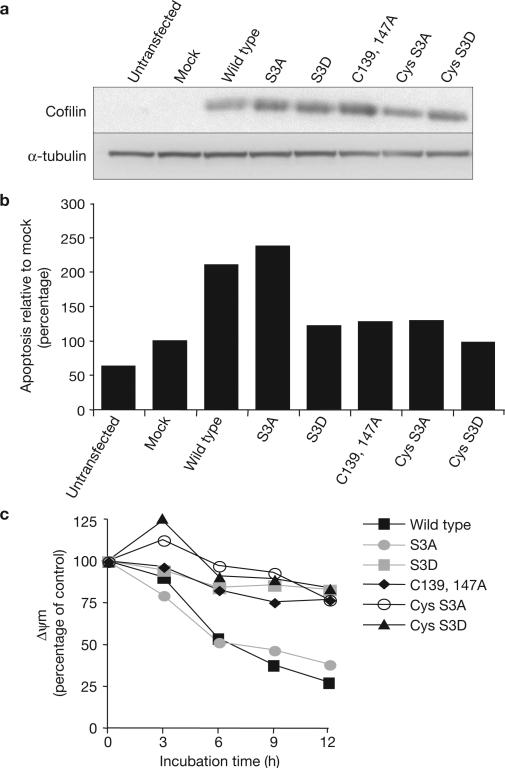

A key mechanism for the regulation of cofilin involves the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of its Ser 3 residue; cofilin is inhibited by phosphorylation17 and translocates to the mitochondria only in its dephosphorylated (active) form18. To determine whether the phosphorylation state of cofilin affects the ability of its oxidized state to mediate apoptosis, we generated and overexpressed mutants of cofilin that either cannot be phosphorylated (mutation of Ser 3 to Ala, S3A) or that mimic a constitutively phosphorylated form of the protein (mutation of Ser 3 to Asp, S3D) and combined these mutations with cofilin that either can or cannot be oxidized at Cys 139 and Cys 147. Overexpression of wild-type cofilin increased apoptosis in response to TnCl by roughly twofold, compared with mock transfected cells (Fig. 5 a, b). Overexpression of the S3A (dephosphorylated) mutant also increased apoptosis in response to TnCl, whereas overexpression of the S3D (phosphorylated) mutant did not. The Cys-Ala mutants prevented S3A and wild-type cofilin from stimulating apoptosis. Similar results were obtained when the effects of cofilin oxidation and phosphorylation were assessed by measuring the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in cells treated with TnCl (Fig. 5c). Wild-type and S3A-mutated cofilin both stimulated loss of Δψm by TnCl whereas S3D and all mutants containing the Cys mutations failed to stimulate apoptosis due to TnCl treatment. Thus, both oxidation and dephosphorylation are required for cofilin to mediate oxidant-induced apoptosis. Oxidative modification of cofilin represents a new mechanism for the control of this highly-regulated protein.

Figure 5.

Cofilin must be dephosphorylated and oxidized for TnCl to cause apoptosis and loss of cellular mitochondrial membrane potential. (a) COS-7 cells were transfected for 6 h with expression plasmids containing different constructs of wild-type or mutated cofilin. Total cell lysates were extracted 48 h after transfection. Expression of wild-type and mutant cofilin proteins was followed by a western-blot immunoassay using an anti-cofilin antibody. α-tubulin protein was used as an internal control for protein loads. The blot shown is representative of two independent experiments. (b) The transfected cells described in a were treated with TnCl (1.5 mM) for 1 h. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry 24 h after TnCl treatment and is calculated relative to the levels in mock transfected cells (lipofectamine plus empty vector). Data are the means from two independent experiments. (c) COS-7 cells transfected as in a were treated with TnCl (1.5 mM), washed and incubated with JC-1 dye (10 μg ml–1) at 37 °C for 20 min. The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) as a function of incubation time was assayed using the ratio of JC-1 red (590 nm) to green (540 nm) fluorescence and expressed as a percentage of control (untreated) cells. Data are the means from two independent experiments carried out in duplicate. S3A, Ser 3 mutated to Ala; S3D, Ser 3 mutated to Asp; C139,147A, Cys 139 and 147 mutated to Ala; Cys S3A, combined mutation of Cys 139 and 147, and Ser 3 to Ala; Cys S3D, combined mutation of Cys 139 and 147 to Ala, and Ser 3 to Asp. See Supplementary Information, Fig. S8 for full scan of a.

Oxidation of cofilin is also required for induction of apoptosis by another key physiological oxidant, H2O2 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5A, B). Because H2O2 alone causes mainly non-apoptotic death (due to the concurrent depletion of ATP from the cells)26, it was used with poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide, which protects cellular energy levels sufficiently to allow apoptosis to proceed. As was seen with TnCl, overexpression of wild-type cofilin increased the ability of H2O2 to induce apoptosis, and this increase was prevented by mutation of Cys 139 and Cys 147 to Ala residues. In contrast, oxidation of cofilin was not required for induction of apoptosis by agents that do not kill cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species (staurosporine and VP-16; Supplementary Information, Fig. S5C).

Chloramines also have the ability to oxidize Met residues7 and cofilin has three Met residues (not including the amino-terminal initiating Met, which is cleaved off during synthesis of the recombinant protein). Using mass spectrometry and recombinant human cofilin, we found that all cofilin Met residues undergo oxidation to Met sulphoxide in response to TnCl treatment, but this occurs at higher TnCl concentrations than are required to oxidize the Cys residues; that is, 30 μM TnCl is sufficient to oxidize ~30–50% of Cys resides, but at this TnCl concentration there is no appreciable oxidation of Met residues (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6A, B). At 100 μM TnCl, all Cys and Met residues in cofilin are oxidized.

To determine the possible role of cofilin Met oxidation in the induction of apoptosis by TnCl, we examined the effect of DTT (dithiothreitol) on mitochondrial swelling in response to cofilin that had been oxidized with 100 μM TnCl. DTT reduces disulphide bonds to free sulphydryls but has no effect on Met sulphoxide residues. As shown in Fig. 2b and c, treatment of oxidized cofilin with DTT completely reversed the ability of cofilin to bind to the mitochondria, to cause cytochrome c release and to induce mitochondrial swelling. A role for cofilin Met oxidation in the induction of apoptosis was also ruled out by mutating all of the Met residues in cofilin to Leu and then overexpressing this protein in COS-7 cells. Unlike the Cys residues, the ability to oxidize cofilin Met residues had no impact on the ability of TnCl to induce apoptosis (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6C, D).

Oxidation of Cys residues in proteins can result in several different oxidation products: intra- and intermolecular disulphides, mixed disulphides and sulphenic acid27. Western blot analysis of cell extracts taken from TnCl-treated lymphoma cells failed to detect any higher-molecular weight species of cofilin, indicating that cellular cofilin does not crosslink with itself or with other proteins in the cell. Instead, according to results from mass spectrometry, cofilin exposed to TnCl undergoes extensive intramolecular disulphide bonding, with no detectible sulphenic acid formation. Mapping of the disulphide linkages showed that four of the six possible intramolecular disulphide bonds are formed in cofilin after exposure to TnCl (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7). Cys 80 is apparently restricted to undergoing crosslinking with Cys 39. As a result, under conditions in which all Cys residues in cofilin are oxidized, the only disulphides found are Cys 139–Cys 147 and Cys 39–Cys 80. Residue Cys 39 can also crosslink with Cys 139, but the oxidation of Cys 80 ties up Cys 39.

To our knowledge, cofilin is the first protein shown to stimulate opening of the PTP depending on its state of oxidation. However, a recent study has also reported that cofilin oxidation impairs its cytoskeletal function in T cells28. The fact that cofilin-mediated apoptosis occurs independently of Bax or Bak activation suggests a direct interaction between oxidized cofilin and the PTP, but the protein–protein interactions involved remain to be elucidated.

Cofilin may not be the only protein that mediates apoptosis in response to oxidative stress29,30. Apoptosis involves several molecular events31 and oxidation at any step can influence the process. Future studies will examine the activities of other proteins oxidized by TnCl to determine whether they have roles in oxidant-induced apoptosis.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecellbiology/.

METHODS

Cell culture and treatments

Exponentially growing JLP-119 human Burkitt's lymphoma cells32 were treated with TnCl in PBS at 5 × 105 cells ml–1. After a 1 h incubation at 37 °C, an equal volume of complete RPMI medium was added and cells were incubated for an additional 5 h to allow apoptosis to proceed. Monkey kidney COS-7 fibroblasts (CRL-1651, ATCC) and wild-type or Bax–/–/Bak–/– double knockout (DKO) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; a gift from R. Youle National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH, MD)24 were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, glutamine (4 mM) and sodium bicarbonate (1.5 g l–1). TnCl was made fresh daily, as described previously2,5,6.

Morphological assessment of cell death using Hoechst/propidium iodide nuclear staining and fluorescence microscopy

Cells were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C with Hoechst 33342 dye (5 μg ml–1; Molecular Probes) in PBS, centrifuged and resuspended in PBS (20 μl) with propidium iodide (PI; 50 μg ml–1). Cells were analysed and counted using fluorescence microscopy as described previously26.

Assessment of apoptosis by FACScan analysis

To determine the percentage of cells with externalized phosphatidylserine (PS), collected cells were centrifuged and resuspended in FACS buffer containing annexin V–FITC (1.25 μg ml–1; PharMingen) and propidium iodide (0.1 mg ml–1), and were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The labelled cells (10,000 per sample) were then analysed by FACScan (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest flow cytometric analysis software. Cells in the lower right dot-plot quadrant (Fig. 3a, PS-positive and PI-negative) are apoptotic and have intact plasma membranes. In these experiments, cells in the upper right quadrant were shown to be late apoptotic using fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence labelling of oxidized thiol proteins and 2D electrophoresis

Protein thiols were blocked by resuspending cells in HEPES buffer (at 2 × 108 cells ml–1), at pH 7.4, containing N-ethylmaleimide (100 mM) and incubating at room temperature for 15 min. After lysing the cells with CHAPS (1% w/v), excess N-ethylmaleimide was removed using Micro Spin Columns (Bio-Rad). Oxidized thiols (disulphides) were reduced with Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP; 1 mM) and were then labelled with 5′-iodoacetamidofluorescein (5-IAF; 200 μM) (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen)15,16,33. Subsequent steps were carried out in low light. Excess 5′IAF and salts were removed with a micro spin column equilibrated with isoelectric focusing (IEF) solution (8 M urea, 10 mM DTT, 2% CHAPS w/v, 0.2% Biolytes 3–10 v/v and bromophenol blue). Extracts containing 50 μg of protein in 125 μl IEF buffer were absorbed overnight onto 10 cm, pH 3–10 (or as indicated in the figure legends) Immobiline Drystrips (Amersham). IEF was carried out on an Ettan IPGphor cell (Amersham) for 9083 Vh. Focused IPG strips were equilibrated for 15 min in 6 M urea, 36% glycerol v/v, 2% SDS w/v, bromophenol blue and 50 mM Tris-HCl, at pH 6.8, and placed onto 0.5% agarose on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and run for 45 min at 200 V. Gels were scanned immediately for fluorescein fluorescence using an Alpha Innotech FluoroChem 8000 imaging system and were analysed with Flicker software (http://www.lecb.ncifcrf.gov/Flicker/).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of oxidized cofilin and mapping of disulphide bonds

Cofilin was alkylated and digested with LysC as described previously34. Full-length cofilin and peptide digests were analysed by reverse phase HPLC with both spectrophotometric and mass spectrometric detection (Agilent model 1100 HPLC and model G1969A mass spectrometer with time of flight detector). Reference mass correction was as described previously35. Oxidation of Cys- and Met-containing peptides was followed by the loss of area of their extracted ion chromatograms. Formation of disulphide linked peptides was followed by the increase of area of their extracted ion chromatograms. Observed absorbance areas (210 nm) were normalized to the area of the peptide containing residues 53–72, as it does not contain Cys or Met residues and its area typically varied by ≤ 10%.

Western-blot immunoassay

The following antibodies were used for a western blot immunoassay: rabbit anti-cofilin (1:1,000), anti-α-tubulin (1:10,000), anti-GAPDH (1:10,000), anti-COX IV (1:1,000) and anti-HSP60 (1:1,000) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse monoclonals anti-α-actin (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-cytochrome c and anti-MnSOD (all at 1:1,000) were from BD Pharmingen. Goat anti-ANT (1:500) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. A mouse monoclonal that is selective for the N terminus of activated Bax was a gift from R. Youle and P. Clerc (both from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH, MD). Horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1:10,000) were from DakoCytomation. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using X-ray film or a Fuji LAS-4000 imager. Quantification was with ImageQuant Total Lab software (Amersham Biosciences) or Fuji quantification software.

Immunoprecipitation of cofilin

TnCl-treated (0.5 mM, 1 h in PBS) and control JLP-119 cells were washed with PBS, incubated on ice for 10 min in lysis buffer (120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM NaPP, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM glycerophosphate, protease inhibitor cocktail, 10% glycerol and 50 mM Tris-HCl, at pH 7.5), and lysed with a N2 bomb (100 PSI for 1 min; 10 × 107 cells ml–1). Cell extracts were centrifuged at 1,400g for 5 min at 0 °C. Supernatants were pre-cleared by incubation with an Ig isotype control (1 μg) attached to Protein G (20 μl; Pierce), rocked for 30 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min at 0 °C. Supernatants were mixed with rabbit anti-cofilin (1 μg; Cell Signaling Technology) and immobilized Protein G (20 μl). After rocking overnight at 4 °C, samples were centrifuged. The pellets were washed and resuspended in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (2×; Invitrogen) plus 1% β-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 5 min and frozen at –20 °C.

Subcellular fractionation

Treated and control JLP-119 or COS-7 cells were washed twice with PBS, incubated on ice for 10 min in lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Mg/Cl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitor and 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4) and lysed with a N2 bomb (100 PSI for 1 min) as described previously36. Lysates were centrifuged at 1,400g for 5 min at 0 °C and the pellets were used as the nuclear fraction. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged twice at 14,000g for 30 min at 0 °C. The final super-natant was the cytosolic fraction plus light membranes. The pellets were a crude mitochondrial fraction plus heavier membranes. All fractions were disrupted by sonication and the addition of 1% CHAPS before western blot analysis.

Oxidation of cofilin in vitro

Purified recombinant human cofilin made in Escherichia coli was purchased from Cytoskeleton. Cofilin (0.25 mg ml–1) was oxidized with TnCl (100 μM) in PBS for 30–60 min at 37 °C. For quantification of Cys and Met oxidation by mass spectrometry, the cofilin was first reduced with DTT, dialysed against PBS containing DTPA (100 μM) and then treated with TnCl. Recombinant cofilin does not contain the N-terminal Met residue, but the residue numbers used throughout the text include Met 1 to be consistent with the numbering system used in the literature.

Isolation of rat liver mitochondria and measurement of the mitochondrial permeability transition

Mitochondria from fresh rat liver were isolated as described previously37 and suspended in buffer B (210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.4, 4.2 mM succinate, 0.5 mM KH2PO4 and 4 μg ml–1 rotenone). Mitochondria were ~92% intact as measured by citrate synthase activity in the supernatant. Opening of the pore causes mitochondrial swelling that was measured as a decrease in light scattering of the mitochondrial suspension38. Mitochondria were suspended in cuvettes in buffer B (0.25 mg ml–1). After a 2 min equilibration period, oxidized or native cofilin was added. Mitochondrial swelling was followed by a decrease in absorbance at 540 nm, 25 °C for 10 min.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

COS-7 cells (1–2 × 106 cells ml–1) were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C with the lipophilic cationic probe 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1; 10 μg ml–1; Molecular Probes) in complete cell culture media, centrifuged, washed, transferred to a 96-well plate (100,000 cells per well) and assayed using a fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices) with excitation at 485 nm and collection of emission spectra between 530–620 nm.Valinomycin (200 nM) was used as a positive control.

Mutation of cofilin Cys, Ser and Met residues, and HSP60 Cys residues by site-directed mutagenesis

All site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the Stratagene QuickChange (Multi) Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The parental plasmid in each case was pCMV--XL5 (Origene).

Cofilin Cys to Ala mutations were generated in the four Cys residues of cofilin (Cys 39, Cys 80, Cys 139 and Cys 147) using the following primers: C39F, 5′-CGCAAGAAGGCGGTGCTCTTCGCGCTGAGTGAGGACAAGAAGAAC-3′; C39R, 5′-GTTCTTCTTGTCCTCACTCAGCGCGAAGAGCACCGCCTTCTTGCG-3′; C80F, 5′-GCTGCCAGATAAGGACGCGCGCTATGCCCTCTATGATGCAACC-3′; C80R, 5′-GGTTGCATCATAGAGGGCATAGCGCGCGTCCTTATCTGGCAGC-3′; C139F, 5′-GAATTGCAAGCAAACGCCTACGAGGAGGTCAAGGACCGC-3′; C139R, 5′-GCGGTCCTTGACCTCCTCGTAGGCGTTTGCTTGCAATTC-3′; C147F, 5′-GGAGGTCAAGGACCGCGCCACCCTGGCAGAGAAGCTGGGGGG-3′; C147R, 5′-CCCCCCAGCTTCTCTGCCAGGGTGGCGCGGTCCTTGACCTCC-3′; C139,147F, 5′-GCAAGCAAACGCCTACGAGGAGGTCAAGGACCGCGCCACCCTGGCAGAGAAG-3′ and C139,147R, 5′-CTTCTCTGCCAGGGTGGCGCGGTCCTTGACCTCCTCGTAGGCGTTTGCTTGC-3′. Cofilin Ser 3 residues were mutated to Ala (S3A) or Asp (S3D) using the following primers: S3A, 5′-CCGGAAACATGGCCGCCGGTGTGGCTGTCTC-3′ and S3D, 5′-CCGGAAACATGGCGACGGTGTGGCTGTCTC-3′. Cofilin Met residues were mutated to Leu in the three Met residues of cofilin (Met 18, Met 74 and Met 115) using the following primers: Met 18, 5′-GGTGTTCAACGACCTGAAGGTGCGTAAG-3′; Met 74, 5′-CGCCACCTTTGTCAAGCTGCTGCCAGATAAGGAC-3′ and Met 115, 5′-GCCCCTTAAGAGCAAACTGATTTATGCCAGCTCC-3′.

HSP60 Cys to Ala mutations were generated in the three Cys residues of HSP60 (Cys 237, Cys 442 and Cys 447) using the following primers: Cys 237, 5′-CATCAAAAGGTCAGAAAGCTGAATTCCAGGATGCC-3′ and Cys 442–447, 5′-TTTGGGAGGGGGTGCTGCCCTCCTTCGAGCCATTCCAGCCTTG-3′.

Transient transfections for overexpression of wild-type and mutant cofilin and HSP60

Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, COS-7 cells (7 × 105) were seeded in 25-cm2 flasks overnight before transfection with 10 μg of each construct. DNA was mixed with the liposome reagent at a ratio of 1:2 before addition to cells. At 6 h after transfection, the medium was removed and fresh medium (5 ml) was added. Transfection efficiency was determined using a pGFP-N1 vector (Clontech) and evaluated by cell counting to be ~80% after 48 h.

siRNA knockdown of endogenous cofilin and rescue of cofilin expression

A pool (Dharmacon) of three sequences homologous to the 3′-untranslated region of cofilin mRNA was used: 5′-CAUGGAAGCAGGACCAGUA-3′, 5′-UAAAUGGAAUGUUGUGGAG-3′ and 5′-ACUCUGUGCUUGUCUGUUU-3′. For optimal siRNA knockdown of endogenous cofilin (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3), 100 nmol of cofilin-1 siRNA or control, non-targeted siRNA (Dharmacon) was transfected into cells.

To re-express wild-type and mutated cofilin in cells containing cofilin-silencing siRNA, the cofilin expression vector was mutated in the 3′-UTR to make it refractory to the siRNA. The sequences at positions 872–873, 904–905 and 973–974 from the ATG start site of the cofilin-1 gene were mutated as follows (mutations underlined): 5′-CCGCAATAGTGACTCTGTGCCGGTCTGTTTAGTTC-3′, 5′- GTATAAATGGAATGCGGTGGAGATGACCCCTCCC-3′ and 5′- CGGCTACTCATGGCGGCAGGACCAGTAAGGGACC-3′. Two days after adding the siRNA, wild-type and mutated cofilin were re-expressed using transient expression vectors as described above.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the members of the Laboratory of Biochemistry for critical comments and discussions, and R. Youle and P. Clerc for providing Bax/Bak knockout cells and an anti-Bax N terminus antibody. The research was supported in part by the Brazilian MCT/CNPq Universal funds (479860/2006-8). F.K. and S.Z. were supported by training grants from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education. This project was funded in part by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract NO1-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The authors would like to dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Earl R. Stadtman for his mentoring and pioneering work in biochemistry and protein oxidation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.K., S.Z., R.L.L. and E.S. carried out project planning, experimental design, experimental work and data analysis. F.K. carried out experiments for Figs 1, 2, 4, 5, S1 and S2, and helped write the manuscript. S.Z. carried out experiments for Figs 3–5 and S3–S7, and helped write the manuscript. R.L.L. carried out experiments for Figs S6 and S7. A.P. carried out experiments and data analysis for Fig. S4. Y.Z. and B.Z. carried out experiments for Fig. 3. L.-R.Y. and T.D.V. carried out experiments and data analysis for Fig. S1. E.S. carried out experiments for Fig. 4, directed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Babior BM. Phagocytes and oxidative stress. Am. J. Med. 2000;109:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00481-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss SJ, Klein R, Slivka A, Wei M. Chlorination of taurine by human neutrophils. Evidence for hypochlorous acid generation. J. Clin. Invest. 1982;70:598–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI110652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee SG, et al. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giles GI. The redox regulation of thiol dependent signaling pathways in cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12:4427–4443. doi: 10.2174/138161206779010549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Englert RP, Shacter E. Distinct modes of cell death induced by different reactive oxygen species: amino acyl chloramines mediate hypochlorous acid-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20518–20526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klamt F, Shacter E. Taurine chloramine, an oxidant derived from neutrophils, induces apoptosis in human B lymphoma cells through mitochondrial damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21346–21352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25:207–218. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prutz WA. Hypochlorous acid interactions with thiols, nucleotides, DNA, and other biological substrates. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;332:110–120. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Biomarkers of myeloperoxidase-derived hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2000;29:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shacter E. Quantification and significance of protein oxidation in biological samples. Drug Metabol. Rev. 2000;32:307–326. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Absolute rate constants for the reaction of hypochlorous acid with protein side chains and peptide bonds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1453–1464. doi: 10.1021/tx0155451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine, and ascorbate. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2001;30:572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newmeyer DD, Ferguson-Miller S. Mitochondria: releasing power for life and unleashing the machineries of death. Cell. 2003;112:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Kwon KS, Rhee SG. Probing cellular protein targets of H2O2 with fluorescein-conjugated iodoacetamide and antibodies to fluorescein. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baty JW, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Proteomic detection of hydrogen peroxide-sensitive thiol proteins in Jurkat cells. Biochem. J. 2005;389:785–795. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bamburg JR, Wiggan OP. ADF/cofilin and actin dynamics in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:598–605. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chua BT, et al. Mitochondrial translocation of cofilin is an early step in apoptosis induction. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:1083–1089. doi: 10.1038/ncb1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu B, Fukada K, Zhu H, Kyprianou N. Prohibitin and cofilin are intracellular effectors of transforming growth factor β signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8640–8647. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannherz HG, et al. Activated cofilin colocalises with Arp2/3 complex in apoptotic blebs during programmed cell death. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2005;84:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinnally KW, Antonsson B. A tale of two mitochondrial channels, MAC and PTP, in apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:857–868. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0722-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chipuk JE, Green DR. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharpe JC, Arnoult D, Youle RJ. Control of mitochondrial permeability by Bcl-2 family members. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1644:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei MC, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowaltowski AJ, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondrial permeability transition and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YJ, Shacter E. Oxidative stress inhibits apoptosis in human lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19792–19798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poole LB, Karplus PA, Claiborne A. Protein sulfenic acids in redox signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klemke M, Wabnitz GH, Funke F, Funk B, Kirchgessner H, Samstag Y. Oxidation of cofilin mediates T cell hyporesponsiveness under oxidative stress conditions. Immunity. 2008;29:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakajima H, et al. The active site cysteine of the proapoptotic protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is essential in oxidative stress-induced aggregation and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26562–26574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeau PJ, Charette SJ, Toledano MB, Landry J. Disulfide Bond-mediated multimerization of Ask1 and its reduction by thioredoxin-1 regulate H2O2-induced c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase activation and apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:3903–3913. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shacter E, Williams JA, Hinson RM, Senturker S, Lee YJ. Oxidative stress interferes with cancer chemotherapy: inhibition of lymphoma cell apoptosis and phagocytosis. Blood. 2000;96:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JR, Yoon HW, Kwon KS, Lee SR, Rhee SG. Identification of proteins containing cysteine residues that are sensitive to oxidation by hydrogen peroxide at neutral pH. Anal. Biochem. 2000;283:214–221. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang DK, et al. Iron regulatory protein 2 as iron sensor. Iron-dependent oxidative modification of cysteine. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14857–14864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine RL. Fixation of nitrogen in an electrospray mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:1828–1830. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senturker S, Tschirret-Guth R, Morrow J, Levine R, Shacter E. Induction of apoptosis by chemotherapeutic drugs without generation of reactive oxygen species. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;397:262–272. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klamt F, Roberto de Oliveira M, Moreira JC. Retinol induces permeability transition and cytochrome c release from rat liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1726:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petronilli V, Cola C, Massari S, Colonna R, Bernardi P. Physiological effectors modify voltage sensing by the cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore of mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21939–21945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.