Abstract

Despite the use of daptomycin alone at high doses (greater than 6 mg/kg of body weight/day) against difficult-to-treat infections, clinical failures and resistance appeared. Recently, the combination daptomycin-cloxacillin showed enhanced efficacy in clearing bacteremia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of daptomycin at usual and high doses (equivalent to 6 and 10 mg/kg/day in humans, respectively) in combination with cloxacillin in a rat tissue cage infection model by MRSA and to compare its efficacy to that of daptomycin-rifampin. We used MRSA strain ATCC BAA-39. In the log- and stationary-phase kill curves, daptomycin-cloxacillin improved the bactericidal activity of daptomycin, especially in log phase. For in vivo studies, therapy was administered intraperitoneally for 7 days with daptomycin at 100 mg/kg/day and 45/mg/kg/day (daptomycin 100 and daptomycin 45), daptomycin 100-cloxacillin at 200 mg/kg/12 h, daptomycin 45-cloxacillin, and daptomycin 100-rifampin at 25 mg/kg/12 h. Daptomycin-rifampin was the best therapy (P < 0.05). Daptomycin 45 was the least effective treatment and did not protect against the emergence of resistant strains. There were no differences between the two dosages of daptomycin plus cloxacillin in any situation, and both protected against resistance. The overall effect of the addition of cloxacillin to daptomycin was a significantly greater cure rate (against adhered bacteria) than that for daptomycin alone. In conclusion, daptomycin-cloxacillin enhanced modestly the in vivo efficacy of daptomycin alone against foreign-body infection by MRSA and was less effective than daptomycin plus rifampin. The benefits of adding cloxacillin to daptomycin should be especially evaluated against infections by rifampin-resistant MRSA and for protection against the emergence of daptomycin nonsusceptibility.

INTRODUCTION

Foreign-body infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are especially difficult to treat because of the limited availability of antibiotic options that are effective against bacterial biofilm and nongrowing (stationary) bacteria (2, 26). Current standard treatment is still based on the use of vancomycin (plus rifampin when the bacteria are susceptible) (12, 31). This approach allowed a cure rate ranging from <50% to >90%, depending on the timing of infection (acute or chronic) and the kind of surgery intervention (debridement or prosthesis exchange) (31).

Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic with concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against growing and nongrowing MRSA (25). However, clinical failure and development of resistance have been reported when daptomycin is used alone against difficult-to-treat infections (14, 24). Although the use of daptomycin at doses greater than 6 mg/kg of body weight/day has been proposed, this dosage does not completely avoid these clinical failures (6). It may be that the use of daptomycin in combination with another drug improves its activity and protects against the emergence of resistant strains or changes in its MIC value.

In the setting of foreign-body infection, in which rifampin plays a major role, the daptomycin-rifampin combination has proved highly effective in experimental models and shows promise as a clinical therapy (8, 10). However, concerns remain regarding the best treatment against rifampin-resistant MRSA or in other situations that do not allow the use of rifampin (i.e., adverse events and drug-drug interactions).

Previous in vitro and in vivo studies of MRSA infections have reported an enhanced efficacy of the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination, despite the fact that the use of beta-lactam antibiotics against MRSA is discouraged (15, 20, 23, 29). The mechanism responsible for this activity has not been conclusively established, but it has been proposed that daptomycin activity against the Gram-positive cell membrane and the synthesis of its precursor peptidoglycan may improve the activity of beta-lactams against MRSA (6). This synergistic effect has been reported mainly with strains that show decreased susceptibility to daptomycin and a seesaw effect (an increasing daptomycin MIC associated with a decreasing cloxacillin MIC) (29). However, the effect has also been observed in the case of daptomycin-susceptible MRSA strains, in which no seesaw effect is seen (15, 20).

The tissue cage infection model is considered an accurate method of mimicking foreign-body infections. In recent years, it has been used to broaden our understanding of this setting and to test the efficacies of several antibiotics alone or in combination (13, 16, 32). Recently, our group standardized an earlier rat tissue cage model of infection (72-h infection) by MRSA and reported the comparative efficacies of several anti-MRSA therapies (8, 17).

In the present study, we aimed to test the efficacy of usual and high doses of daptomycin (equivalent to 6 and 10 mg/kg/day in humans, respectively) in combination with cloxacillin using a rat tissue cage infection model caused by a daptomycin-susceptible MRSA strain. We also aimed to compare the efficacy of this combined therapy with that of daptomycin plus rifampin, which previously proved to be the most active treatment in this setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganism.

The methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain HUSA 304 (ATCC BAA-39) was used for all in vitro and in vivo studies.

Antimicrobial agents.

For in vitro experiments, the purified powder of the antibiotic was resuspended in accordance with laboratory recommendations. Daptomycin was kindly supplied by Novartis (Barcelona, Spain), and cloxacillin came from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain).

For in vivo experiments, we diluted the commercial products to achieve a suitable final volume for administration to animals.

In vitro studies.

In all in vitro experiments with daptomycin, the medium was supplemented with 50 μg/ml of calcium (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain).

(i) Determination of MICs and MBCs.

The MICs and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) for all antibiotics were determined in the log phase in accordance with standard recommendations (1). The MIC was defined as the minimum concentration of antibiotic that was able to inhibit visible bacterial growth, and the MBC was defined as the lowest concentration which killed 99.9% of the original inoculum. We also determined MBCs during the stationary phase of growth. We used a methodology previously reported in detail elsewhere, which has proved to be a reliable approach for correlating the in vivo efficacy of antibiotics in the tissue cage infection model (16, 30). The MBCs were defined as described above.

(ii) Twenty-four-hour kill curves in log and stationary phases.

We performed kill curves in the log phase using standard methodology with bacterial inocula of 105 CFU/ml (19). We also carried out kill curves with higher inocula (108 CFU/ml) in the log phase; for these experiments, bacteria were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) for 3 h; later, they were centrifuged and resuspended to use a MHB macrodilution method with a final inoculum of 108 CFU/ml under exponential-growth conditions. For kill curves in the stationary phase, we used a methodology described elsewhere (16). All these 24-h kill curves were carried out in triplicate.

For studies in log phase, we selected prefixed concentrations of antibiotics that represent subinhibitory and clinically achievable levels above the MIC (0.25× to 32× MIC for daptomycin and 1/4×, 1/2×, 1×, and 2× MIC for cloxacillin). Due to the bacterial tolerance to antibiotics expressed in stationary phase, the drug concentrations tested were higher than those in log phase; these concentrations were equivalent to the peak and trough total levels achieved in the tissue cage fluid (TCF).

For all experiments, bactericidal activity was defined as a ≥3-log10 decrease in the initial inoculum in CFU/ml at 24 h. The results of the combination were compared with those of the most active single drug; synergy, indifference, and antagonism were then defined as a ≥2-log increase in killing, <2-log change (increase or decrease), and ≥2-log decrease, respectively.

To avoid carryover antimicrobial agent interference, the sample was placed on the plate in a single streak down the center and allowed to be absorbed into the agar until the plate surface appeared dry; the inoculum was then spread over the plate. As described in more detail elsewhere (7), this methodology was checked by comparing the results obtained with the centrifugation and resuspension of the fluid from tubes of killing curves.

Animal studies.

The animal model was approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments at the University of Barcelona. We used male Wistar rats weighing 230 to 250 g at the beginning of the experiments. They were in the stabulary for a week (under controlled conditions of food, drink, temperature, and light) to ensure they were healthy before the experiment's start. The rats were given food and water ad libitum throughout the study.

We used a 72-h tissue cage infection model. This earlier foreign-body infection rat model was previously standardized by our group, and all the methodology used has been reported in our studies (17). Briefly, two Teflon tissue cages with two coverslips (CV) each were subcutaneously implanted in male Wistar rats. After 3 weeks, the TCF was checked for sterility and infected with 0.1 ml of a MRSA preparation (106 CFU/ml). At 72 h postinoculation (day 1), TCF was obtained to quantify bacterial counts; therapy was then started and administered intraperitoneally for 7 days. One and four days after the end of treatment (days 8 and 11, respectively) TCF was again recovered to quantify bacterial counts. On day 11, animals were sacrificed, and coverslips were removed to quantify adherent bacteria.

All the procedures for processing TCF and coverslips have been reported to be harmless for bacteria and have been described in detail elsewhere (5, 13, 16). Briefly, the TCF obtained was sonicated to disrupt bacterial clumps; a sample of 100 μl of the sonicated fluids and their 10-fold dilutions was plated on a Trypticase soy agar plate with 5% sheep blood for 48 h at 37°C, and then bacterial counts were recorded as log CFU per ml. Coverslips from tissue cages were rinsed three times in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); they were then incubated in 1 ml of PBS with trypsin (6 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) for 20 min at 37°C, and later the same samples were sonicated to recover adherent bacteria. Finally, this fluid was used to perform bacterial counts and to screen resistant bacteria (see below).

The criterion of efficacy was defined as the decrease in bacterial counts from TCF between the beginning and end of treatment; it was evaluated twice, on days 8 and 11. The antibiotic efficacy against adherent bacteria from coverslips removed on day 11 was also evaluated by determining the bacterial counts. Finally, the cure rate of infection from the coverslips was calculated on day 11; it was defined as the percentage of samples with bacterial counts under the limit of detection with respect to the total samples.

For all cases, the lower limit of detection of bacterial counts was 10 CFU/ml.

Therapeutic groups.

All antibiotics were administered intraperitoneally. Animals were divided into therapeutic groups and received the following dosages: daptomycin at 100 mg/kg/day (daptomycin 100; equivalent to 10 mg/kg/day in humans), daptomycin at 45 mg/kg/day (daptomycin 45; equivalent to 6 mg/kg/day in humans), daptomycin at 100 mg/kg/day plus cloxacillin at 200 mg/kg/12 h, daptomycin at 45 mg/kg/day plus cloxacillin, and daptomycin at 100 mg/kg/day plus rifampin at 25 mg/kg/12 h. Controls received saline solution.

Pharmacokinetic studies.

All the methodology used has been described in detail elsewhere (16, 18). On the basis of previous reports, we used the dose of antibiotic that achieved pharmacodynamic parameters in the TCF close to those in human serum (3, 27). For daptomycin and rifampin, we adjusted the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) and maximum concentration of drug in TCF (Cmax) values, respectively. For the particular case of cloxacillin, we selected the dose used in our previous studies that mimics the usual dosage in humans due to the inability to optimize the pharmacodynamic parameters against the MRSA strain used (16).

All drug concentrations were determined using a bioassay method (4). The lower detection limit (μg/ml) and the intra-assay coefficient (R2) were 1 and 0.98 for cloxacillin, 0.25 and 0.99 for rifampin, and 1 and 0.99 for daptomycin, respectively. We achieved a good correlation between the duplicate assays with the antibiotics.

Peak and trough levels in TCF were determined on day 4 of therapy for each drug to check the equilibrium test concentrations during treatment.

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters achieved by the selected dosage of each antibiotic were reported in our earlier studies (16, 17). The Cmax (μg/ml) and AUC0-24 (μg · h/ml) in serum and TCF were 103, 830, 26, and 795, respectively, for daptomycin at 45 mg/kg, 140, 1,200, 40, and 1,100 for daptomycin at 100 mg/kg, and 24, 277, 6.6, and 304 for rifampin. The Cmax in TCF for cloxacillin was 43 μg/ml; the AUC and time above the MIC were not determined.

Resistance studies.

The screening of resistant strains from the TCF at day 8 and day 11 and from coverslips at day 11 was performed using agar plates containing 1 μg/ml for daptomycin and rifampin. The plates containing daptomycin were supplemented with calcium (50 μg/ml).

In all cases, a sample of 100 μl from the TCF or fluid from processed coverslips was inoculated onto the agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Results were interpreted as positive (some macroscopic growth) or negative (no growth).

For the particular case of daptomycin, resistant strains obtained from screening agar plates were recovered to determine MICs following standard methodology (1).

Statistical analysis.

All bacterial counts are presented as log numbers of CFU per milliliter (means ± standard deviations [SD]). Differences in bacterial counts between treated and untreated animals were evaluated for statistical significance using analysis of variance. An unpaired Student t test with Bonferroni's correction was used to determine statistical significance. For all tests, differences were considered to be statistically significant when P values were <0.05.

RESULTS

In vitro studies. (i) MICs and MBCs.

The MICs and MBCs (μg/ml) of daptomycin, rifampin, and cloxacillin in the log phase (with 105 CFU/ml) were, respectively, 1 and 4, 0.03 and 0.5, and 16 and >32. The MBCs for these antibiotics in the stationary phase were 24, >8, and >32 μg/ml, respectively.

(ii) Twenty-four-hour kill curves.

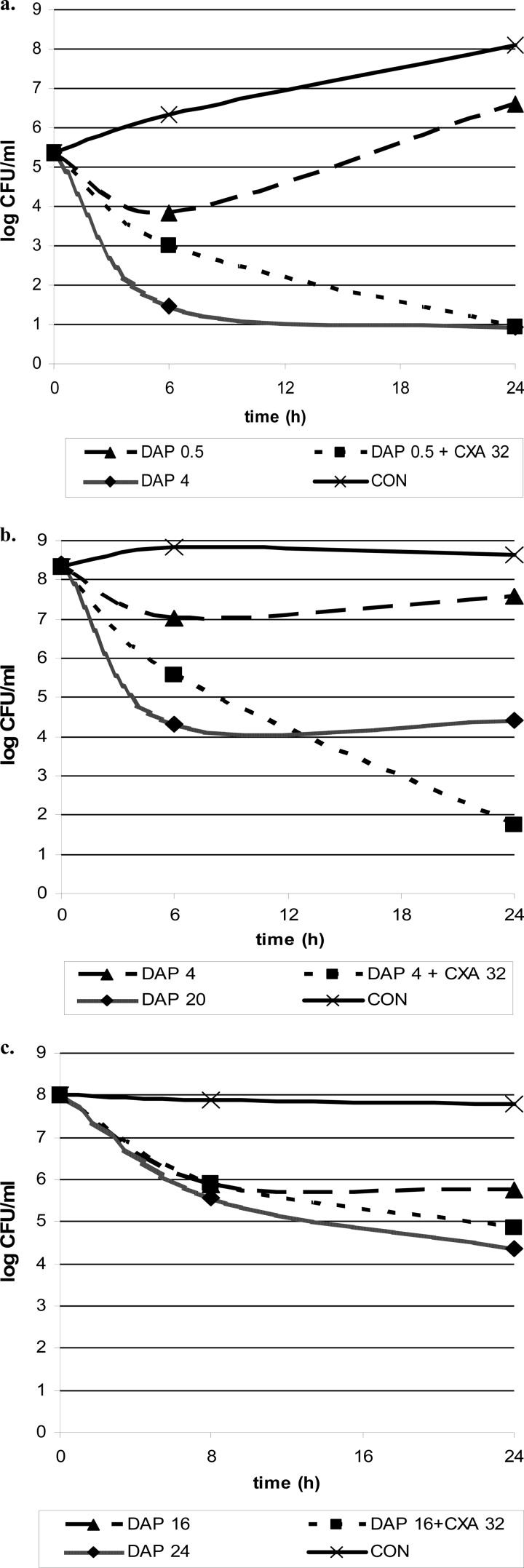

Cloxacillin alone showed no activity in either study, whereas daptomycin alone achieved a bactericidal effect in all phases (daptomycin concentrations of 4, 20, and 24 μg/ml in log phase with standard inocula, log phase with high inocula, and stationary phase, respectively). The combination daptomycin plus cloxacillin also achieved bactericidal activity in all studies.

In log phase with the standard inoculum of 105 CFU/ml, the combination was synergistic and achieved a bactericidal effect even with subinhibitory concentrations (below the MIC value) of daptomycin in combination with cloxacillin concentrations between 4 and 32 μg/ml (the concentration of daptomycin in combination with cloxacillin that allowed bactericidal activity was 0.5 μg/ml; the improvement in the daptomycin concentration value when it was used in combination with respect to that when it was used alone was 8-fold). With the higher inoculum of 108 CFU/ml in log phase, the activity of daptomycin plus cloxacillin was also synergistic and bactericidal (concentration of daptomycin, 4 μg/ml; improvement of 5-fold). Finally, against high bacterial inocula in stationary phase, the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination was not strictly synergistic but allowed bactericidal killing with a greater range of daptomycin concentrations (concentration of daptomycin, 16 μg/ml; improvement of 1.5-fold). Overall, the addition of cloxacillin to daptomycin always improved the in vitro activity of daptomycin, especially in log phase.

The most representative results of kill curves in the log and stationary phases for daptomycin in combination with cloxacillin are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig 1.

Time-kill curves for log phase with a bacterial inoculum of 105 CFU/ml (a) or 108 CFU/ml (b) and for stationary phase (c) with the antibiotics alone and in combination. Concentrations are in μg/ml. Abbreviations: DAP, daptomycin; CXA, cloxacillin; CON, growth control (no antibiotic).

Animal studies.

Sixty-five animals were used (130 tissue cages); since some tissue cages were lost due to spontaneous shedding, at the beginnings of experiments 120 cages were used. There were no significant differences between the groups on day 1 (beginning of the treatment). The bacterial counts (mean log CFU/ml ± SD) were as follows: 6.46 ± 0.9 for daptomycin 100 (n = 20), 6.17 ± 0.8 for daptomycin 45 (n = 21), 6.56 ± 0.8 for daptomycin 100 plus cloxacillin (n = 24), 6.45 ± 0.8 for daptomycin 45 plus cloxacillin (n = 22), 6.24 ± 0.7 for daptomycin 100 plus rifampin (n = 16), and 6.66 ± 1 for the controls (n = 17).

(i) Efficacy of antibiotics.

The decreases in the bacterial counts from the TCF at days 8 and 11 and bacterial counts from CV are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Decreases in bacterial counts from TCF at day 8 and day 11 and bacterial counts recovered from CV at day 11a

| Treatment (nb) | Decrease in bacterial count from TCF |

Bacterial count from CV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D8 | D11 | ||

| DAP 45 (21) | −2.76 (±1.3) | −2.80 (±1.4) | 2.22 (±1.4) |

| DAP 100 (20) | −2.82 (±0.7) | −3.24 (±0.7) | 1.88 (±0.8) |

| DAP 45 + CXA (22) | −3.24 (±1.2) | −3.19 (±1.1) | 1.40 (±0.9)*# |

| DAP 100 + CXA (24) | −3.19 (±1.1) | −3.22 (±1.1) | 1.43 (±0.7)*# |

| DAP 100 + RIF (16) | −4.94 (±0.8)** | −4.88 (±1.4)** | 0.91 (±0.2)** |

| Control (17) | 0.39 (±0.8) | 0.85 (±0.8) | 5.50 (±0.8) |

Bacterial counts are expressed in mean log CFU/ml (±SD). All therapeutic groups performed significantly better than controls (P < 0.05). *, P < 0.05 versus results for DAP 45; **, P < 0.05 versus all results for all therapies; #, P = 0.09 versus results for DAP 100. D8, day 8; D11, day 11.

n, number of TCF samples.

All therapeutic groups always performed significantly better than controls (P < 0.05).

Daptomycin-rifampin was the most effective treatment in eradicating either bacteria from TCF (P = 0.001) or adhered bacteria from CV (P = 0.01). Daptomycin 45 was significantly less active than either daptomycin-cloxacillin combination as determined by bacterial counts from CV. Also, daptomycin 100 had lower efficacy (P = 0.09, bacterial counts from CV) than the combination daptomycin-cloxacillin. There were no differences between the two dosages of daptomycin plus cloxacillin in any situation (bacteria from TCF or adhered bacteria from CV).

The cure rate evaluated for the coverslips showed that daptomycin plus rifampin (cure rate, 94%) was significantly the best treatment (P ≤ 0.008). The overall effect of the addition of cloxacillin to daptomycin (either dosage; cure rate, 54%) resulted in a significantly greater cure rate than that for daptomycin alone (cure rate, 26%; P = 0.005).

(ii) Resistance studies.

Among monotherapies, resistant strains emerged using daptomycin at 45 mg/kg/day (in 5% of cases) but not with daptomycin at 100 mg/kg/day. All cloxacillin and rifampin combinations protected against the appearance of daptomycin or rifampin resistance.

All daptomycin-resistant strains in the daptomycin-at-45-mg/kg/day group showed a MIC value of 2 μg/ml (2-fold increase with respect to that for the wild-type strain).

DISCUSSION

The present study focused on the efficacy of the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination against foreign-body infection by MRSA.

Daptomycin has rapid anti-MRSA bactericidal activity (25). This promising drug has been introduced into clinical practice in recent years, but clinical failures and the development of resistance when administered alone at usual doses (6 mg/kg/day) have appeared (14, 24). Recently, the use of daptomycin at higher doses (8 to 10 mg/kg/day) was also clinically ineffective in clearing persistent MRSA bacteremia and in preventing the emergence of nonsusceptibility (6).

Earlier experimental results by our group using a tissue cage MRSA infection model, which mimics prosthetic joint infections in humans, indicated high efficacy of daptomycin among anti-MRSA monotherapies but a low rate of cure of the infection despite the use of high doses equivalent to 10 mg/kg/day (8, 17).

According to previous work (8), it may be that the use of daptomycin in combination improves its activity and protects the emergence of resistance against certain difficult-to-treat infections, such as prosthetic joint infections and endocarditis, which may involve high bacterial inocula and may increase the risk of the emergence of resistance.

In the setting of prosthetic joint infection by MRSA, the best treatment is still not well defined. Rifampin in combination should be used whenever possible because of its benefits against nongrowing bacteria and biofilm-related infections (31, 33). Recently, using the tissue cage model of infection due to MRSA, we and others reported the highest levels of efficacy with the daptomycin-rifampin combination (8, 10). More concerns remain when rifampin-resistant MRSA strains are responsible for the infection or in those situations that do not allow the use of rifampin (i.e., adverse events and drug-drug interactions). Although there is marked geographical variation in the prevalence of rifampin resistance worldwide, the epidemic nature of MRSA infections may cause higher local rates of resistance (9, 11). In this way, the need for new drugs or the use of other antimicrobial combinations is imperative.

Although MRSA strains are considered resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, previous reports showed an improvement of the in vitro efficacy of daptomycin by the addition of cloxacillin against MRSA, although in one of these studies the effect was described as strain dependent (15, 20, 23, 29).

In the present study, we again confirmed the in vitro bactericidal activity of daptomycin in both phases of growth, although this killing was interfered with by the presence of high inocula and bacteria in the stationary phase (as shown by the MBC values). In agreement with previous studies, the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination in log phase achieved a synergistic and bactericidal effect using either standard (105 CFU/ml) or high (108 CFU/ml) inocula. The mechanisms underlying this effect are not clear, and their identification is beyond the scope of the present study (6, 20). To our knowledge, previous studies testing the efficacy of this combination in stationary phase are lacking. In this setting, the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination also improved the bactericidal effect of daptomycin. Overall, the in vitro bactericidal effect of daptomycin alone was enhanced by the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination in all the studies, but the effect was lower when high bacterial inoculums were used in stationary phase. The improvements in the daptomycin bactericidal concentration with the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination were 8-fold, 5-fold, and 1.5-fold when using standard inocula (log phase), high inocula (log phase), and in stationary phase, respectively.

Regarding in vivo efficacy, our results corroborated those of previous studies indicating that the emergence of resistant strains was not prevented by the use of standard doses of daptomycin (equivalent to 6 mg/kg/day in humans) but was prevented by high doses (8, 21, 22). Overall, the addition of cloxacillin to both doses improved the efficacy of daptomycin alone in a moderate manner (evaluated against bacteria from TCF or adherent bacteria from coverslips) and always protected against the emergence of daptomycin-resistant strains. Moreover, the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination was significantly less effective than the combination of high doses of daptomycin plus rifampin, which was confirmed as the best treatment and ensured protection against the appearance of resistance (8, 10). A limitation of our study is the fact that these results were obtained using only one MRSA strain, and thus further work should provide similar data with other MRSA strains, as previous in vitro studies have confirmed (15, 20, 23, 29).

To our knowledge, there is currently little information on the in vivo efficacy of the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination, and none of the studies carried out to date used a foreign-body infection model. In previous work using a rabbit model of endocarditis this combination was evaluated only against daptomycin-nonsusceptible MRSA strains and showed greater efficacy than daptomycin alone (29). The authors attributed this additive activity to the presence of MRSA strains with a seesaw effect (increasing daptomycin MIC associated with decreasing cloxacillin MIC). Unfortunately, because of the high efficacy of daptomycin alone, they did not evaluate the efficacy of the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination against a daptomycin-susceptible MRSA strain.

Recently, the clearance of persistent MRSA bacteremia in humans with the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination was described (6). The in vitro studies in log phase showed an enhanced killing of the combination with respect to daptomycin alone; the effect was more evident against daptomycin-resistant strains, but it was also recorded with daptomycin-susceptible MRSA strains.

Our results suggest that the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination may be considered as an alternative anti-MRSA therapy, even in the setting of daptomycin-susceptible infections. As is well known, the in vitro killing of antimicrobials in stationary phase correlates better with the in vivo efficacy against foreign-body infection (28, 30); in contrast, high inocula in the log phase of growth are commonly used to correlate the efficacy in endocarditis models (21, 22). We observed modest increases in in vitro killing in stationary phase and in the in vivo model but also noted a high increase in the in vitro log phase. Its possible clinical usefulness should be better defined and may vary depending on the kind of infection involved.

In conclusion, the daptomycin-cloxacillin combination improved the in vitro bactericidal activity of daptomycin, especially against bacteria in the log phase of growth. Against foreign-body infection by MRSA, this combination modestly enhanced the in vivo efficacy of daptomycin alone and was less effective than daptomycin plus rifampin. In this setting, the potential benefits of adding cloxacillin to daptomycin should be especially evaluated against infections by rifampin-resistant MRSA. Further studies should compare the efficacy of this combination versus other those of alternative therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a research grant from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS 11/013), and grants from the Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI C03/14 and REIPI RD06/0008); C.G. was supported by a grant from the REIPI.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard, 8th ed, M7-A8 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Craig WA. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chapin-Robertson K, Edberg SC. 1991. Measurements of antibiotics in human body fluids: techniques and significance, p 295–366 In Lorian V. (ed), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams & Wilkins Co., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chuard C, et al. 1991. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus recovered from infected foreign body in vivo to killing by antimicrobials. J. Infect. Dis. 163:1369–1373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dhand A, et al. 2011. Use of antistaphylococcal beta-lactams to increase daptomycin activity in eradicating persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: role of enhanced daptomycin binding. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:158–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garrigos C, et al. 2011. Efficacy of tigecycline alone and with rifampin in foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. 63:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garrigos C, et al. 2010. Efficacy of usual and high doses of daptomycin in combination with rifampin versus alternative therapies in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:5251–5256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gasch O, et al. 2011. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus clone related to the early pandemic phage type 80/81 causing an outbreak among residents of three occupational centres in Barcelona, Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. John AK, et al. 2009. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2719–2724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson AP. 2011. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the European landscape. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66(Suppl. 4):iv43–iv48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu C, et al. 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lucet JC, et al. 1990. Treatment of experimental foreign body infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2312–2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mangili A, Bica I, Snydman DR, Hamer DH. 2005. Daptomycin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1058–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miro JM, et al. 2010. In vitro activity of daptomycin plus oxacillin against methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains, abstr E-1550. Abstr. 50th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murillo O, et al. 2006. Efficacy of high doses of levofloxacin in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4011–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murillo O, et al. 2009. Efficacy of high doses of daptomycin versus alternative therapies against experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4252–4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murillo O, et al. 2008. Antagonistic effect of rifampin on the efficacy of high-dose levofloxacin in staphylococcal experimental foreign-body infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3681–3686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NCCLS 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. M26-A NCCLS, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rand KH, Houck HJ. 2004. Synergy of daptomycin with oxacillin and other beta-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2871–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rose WE, Leonard SN, Rybak MJ. 2008. Evaluation of daptomycin pharmacodynamics and resistance at various dosage regimens against Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibilities to daptomycin in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3061–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakoulas G, et al. 2008. Evaluation of endocarditis caused by methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus developing nonsusceptibility to daptomycin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:220–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scheetz M, Reddy P, Postelnick M, Flaherty J. 2005. In vivo synergy of daptomycin plus a penicillin agent for MRSA? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:398–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skiest DJ. 2006. Treatment failure resulting from resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to daptomycin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:655–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steenbergen JN, Alder J, Thorne GM, Tally FP. 2005. Daptomycin: a lipopeptide antibiotic for the treatment of serious Gram-positive infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stewart PS, Costerton JW. 2001. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet 358:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trampuz A, Wenk M, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W. 2000. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of levofloxacin against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in human skin blister fluid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1352–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Widmer AF, Frei R, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W. 1990. Correlation between in vivo and in vitro efficacy of antimicrobial agents against foreign body infections. J. Infect. Dis. 162:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang SJ, et al. 2010. Daptomycin-oxacillin combinations in treatment of experimental endocarditis caused by daptomycin-nonsusceptible strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with evolving oxacillin susceptibility (the “seesaw effect”). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3161–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zimmerli W, Frei R, Widmer AF, Rajacic Z. 1994. Microbiological tests to predict treatment outcome in experimental device-related infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:959–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. 2004. Prosthetic-joint infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1645–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zimmerli W, Waldvogel FA, Vaudaux P, Nydegger UE. 1982. Pathogenesis of foreign body infection: description and characteristics of an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 146:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. 1998. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA 279:1537–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]