LETTER

Colistin appears more and more frequently as a last-line defense therapy against nosocomial infections due to multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria (8). For parenteral administration, colistin is used as a prodrug, colistin methanesulfonate (CMS), which is less toxic but inactive and hydrolyzed in vivo into colistin. Its pharmacokinetics is complex but better understood recently (1, 2, 4, 9). Yet although peritonitis is the second-greatest cause of lethal infections in critical care patients (10), colistin distribution in patients' peritoneal fluid (PF) has never been described.

An 85-year-old man weighing 69 kg underwent surgical resection to remove colon carcinoma. His creatinine clearance (CLcreat) was stable at 35 ml/min. On day 4 postsurgery, he developed an intra-abdominal infection requiring further surgery and drainage of the abdominal cavity. Antibiotic therapy was started with a combination of piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin. Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were isolated from the abdominal cavity, and amikacin was switched to colistin. CMS was given intravenously over 60 min, starting with an initial loading dose of 8 million international units (MIU), corresponding to 640 mg of CMS. A maintenance dose was selected according to equation 1, with a target colistin plasma concentration ranging between 2 and 4 μg/ml (2).

| (1) |

For these calculations, CMS renal clearance (CLR) was set at 85% of CLcreat, CMS nonrenal clearance (CLNR) was considered equal to 27 ml/min, and colistin clearance (CLcoli) was considered equal to 35 ml/min, as previously estimated in critical care patients (6). Accordingly, a maintenance dose equal to 2 MIU/8 h, corresponding to a predicted average plasma colistin concentration at steady state (CSS,avg) of 3.0 μg/ml, was selected. Plasma and PF samples were rapidly frozen at −80°C pending the assay. CMS and colistin concentrations were measured in plasma and PF after the loading dose and at steady state (after the 7th dose) by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (5).

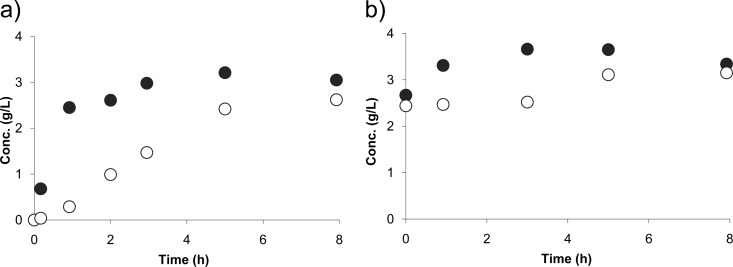

The CMS peak concentration in plasma obtained after the loading dose (59 μg/ml) was about 3-fold higher than the peak concentration in plasma obtained after the maintenance dose at steady state (18 μg/ml). Corresponding peak concentrations in PF were much lower (3.7 μg/ml and 0.8 μg/ml, respectively), a result which may be due to a slow distribution and/or rapid conversion of CMS in colistin within PF. Following the CMS loading dose, colistin concentrations increased more slowly in PF than in plasma, attesting for the relatively slow distribution (Fig. 1a), but at steady state, colistin PF concentrations compared favorably with plasma concentrations, which were close to the values predicted from equation 1 (Fig. 1b). In comparison, concentrations of carbapenems (3, 7) were shown to be much lower in PF than in plasma due to peripheral degradation in patients with peritonitis. Noticeably precise characterization of CMS and colistin PF distribution, as well as colistin antimicrobial activity, should ideally rely on unbound concentrations, which are unfortunately almost impossible to determine in practice, when both compounds are present in the medium. Yet this case report suggests that colistin presents pharmacokinetic characteristics, in particular chemical stability, in favor of its use for the treatment of peritonitis.

Fig 1.

Plasma (●) and PF (○) colistin concentrations measured in a patient with peritonitis after an initial 8-MIU CMS loading dose (a) and at steady state following multiple CMS administrations at 2 MIU every 8 h (b).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Ministry of Health (PHRC National 2009).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 April 2012

Contributor Information

Olivier Mimoz, CHU Poitiers Poitiers, France.

Franck Petitpas, CHU Poitiers Poitiers, France.

Nicolas Grégoire, Université de Poitiers UFR Médecine-Pharmacie Poitiers, France.

William Couet, Inserm U-1070 Poitiers, France.

REFERENCES

- 1. Couet W, et al. 2011. Pharmacokinetics of colistin and colistimethate sodium after a single 80-mg intravenous dose of CMS in young healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89:875–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Couet W, Gregoire N, Marchand S, Mimoz O. 2012. Colistin pharmacokinetics: the fog is lifting. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:30–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. 2010. Kinetics of imipenem distribution into the peritoneal fluid of patients with severe peritonitis studied by microdialysis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 49:323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garonzik SM, et al. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3284–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gobin P, Lemaitre F, Marchand S, Couet W, Olivier JC. 2010. Assay of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate in plasma and urine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1941–1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gregoire N, et al. 2011. Population pharmacokinetic study of colistin in combined healthy volunteers and patients with severe Gram-negative multidrug-resistant infections, poster P804. 21st ECCMID, Milan, Italy [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karjagin J, et al. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem determined by microdialysis in the peritoneal fluid of patients with severe peritonitis associated with septic shock. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 83:452–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li J, et al. 2006. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plachouras D, et al. 2009. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of colistin methanesulfonate and colistin after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with infections caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3430–3436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vincent JL, et al. 2009. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302:2323–2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]