Abstract

Retrospective review from 11 Canadian hospitals showed increasing incidence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from 0.12 per 1,000 inpatient days during 2005 to 0.47 per 1,000 inpatient days during 2009. By 2009, susceptibility rates of ESBL-positive E. coli/K. pneumoniae were as follows: ciprofloxacin, 12.8%/9.0%; TMP/SMX, 32.9%/12.2%; and nitrofurantoin, 83.8%/10.3%. Nosocomial and nonnosocomial ESBL-producing E. coli isolates had similar susceptibility profiles, while nonnosocomial ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae was associated with decreased ciprofloxacin (P = 0.03) and nitrofurantoin (P < 0.001) susceptibilities.

TEXT

Multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains have become a global concern. Increasing incidence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) may be attributable, in part, to the successful clonal dissemination of the CTX-M-15 plasmid worldwide (2, 22). Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are also emerging across the globe (3, 9, 15). Low prevalence rates (4.1%) of ESBL-producing E. coli have been described in Canada, predominantly due to CTX-M β-lactamases (23), and only sporadic cases of imported CRE have been reported (13, 23).

Infections due to ESBL-E are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay, and cost (11). Therapeutic alternatives for ESBL-E are limited with increasing resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics (6), resulting in a high likelihood of inappropriate initial empirical therapy (8). Carbapenems continue to be the treatment choice for severe infections due to ESBL-E (16), but resistance to these agents is also emerging (9, 15).

In light of these concerns regarding ESBL-E, a retrospective review of incidence rates and susceptibility profiles for ESBL-E was conducted in 11 large hospitals (five academic and six community) in Toronto, Canada, from 2005 to 2009. Participating hospital characteristics have been previously described (12). All ESBL-producing Ambler class A Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates were included. Susceptibility testing was performed utilizing VITEK2 (bioMérieux, St. Laurent, Quebec, Canada) in 10 hospitals and Phoenix2 (Becton Dickenson, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) in the remaining hospital. Isolates intermediate or resistant to an extended-spectrum cephalosporin (cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, or ceftazidime) were confirmed as ESBL-E with double disk diffusion testing as per the 2009 CLSI standards (1). Mean incidence rates were calculated after each site was adjusted per 1,000 inpatient days. Only the first clinical isolate from any one patient was included. Isolates were defined as nosocomial if they were identified from cultures obtained 3 or more days after admission to the hospital in patients without a prior specimen yielding ESBL-E. Statistical analysis was performed utilizing the chi-squared test or the chi-squared test for trend, as well as a multivariate analysis (SAS 9.2; Cary, NC).

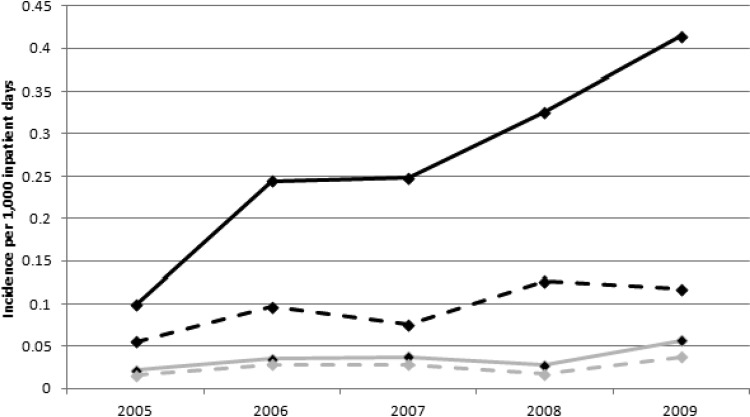

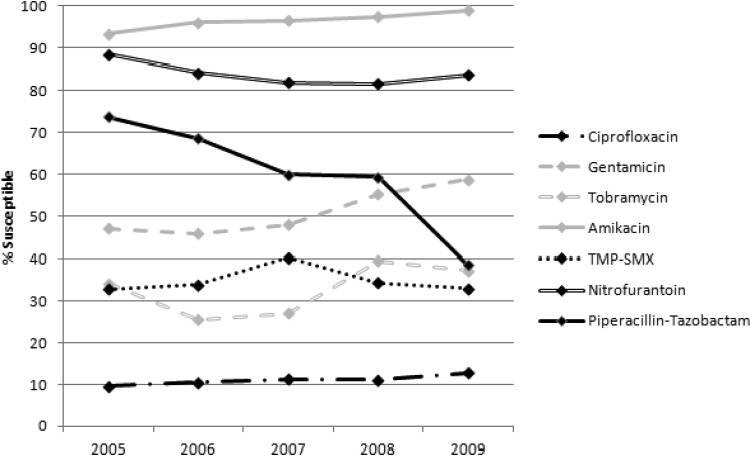

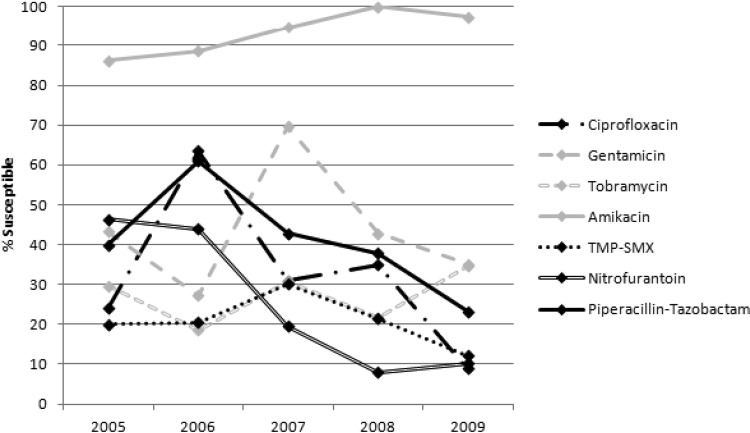

Overall incidence of ESBL-E per 1,000 inpatient days increased as follows: 0.12 in 2005, 0.28 in 2006, 0.29 in 2007, 0.35 in 2008, and 0.47 in 2009. Incidence rates stratified by organism are shown in Fig. 1. There were 1,994 ESBL-E isolates over the 5 years: 1,736 E. coli and 258 K. pneumoniae. Isolates were most commonly from a urinary source (74.1%) but were also recovered from blood (12.0%), respiratory tract (5.2%), wound (4.6%), abscess/fluid (2.7%), and other sources (1.4%). Figures 2 and 3 describe the susceptibility profile of E. coli and K. pneumoniae over time. Declining susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam in E. coli (P < 0.001) and K. pneumoniae (P = 0.01) was observed. With respect to E. coli, susceptibility to non-β-lactam agents was stable except for improved susceptibility to aminoglycosides (gentamicin and amikacin, P < 0.001; tobramycin, P = 0.002). For K. pneumoniae, susceptibility rates decreased for ciprofloxacin (P < 0.001) and nitrofurantoin (P < 0.001) over the course of the study. Both of these agents were also found to have reduced susceptibilities in nonnosocomial settings and community hospitals (Table 1). This study identified 3 carbapenem-resistant E. coli isolates: 1 in 2008 and 2 in 2009. Multivariate analysis adjusting for date of culture, nosocomial status, and hospital type did not differ from the univariate analysis. In addition, resistance to ≥3 non-β-lactam antimicrobial classes occurred in 30.2% of E. coli and 40.5% of K. pneumoniae isolates and did not change significantly over time.

Fig 1.

Overall (solid lines) and nosocomial (dashed lines) incidence of ESBL-E clinical isolates between 2005 and 2009. Black, E. coli; gray, K. pneumoniae.

Fig 2.

Susceptibility profile of ESBL-producing E. coli recovered over a 5-year period.

Fig 3.

Susceptibility profile of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae recovered over a 5-year period.

Table 1.

Comparison of susceptibility rates in E. coli and K. pneumoniae with respect to nosocomial status and hospital type

| Organism and drug | Valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosocomial | Nonnosocomial | P value | Academic | Community | P value | |

| E. coli | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 12.6 (76/601) | 10.7 (106/995) | 0.26 | 11.8 (109/927) | 10.9 (73/669) | 0.66 |

| Gentamicin | 49.1 (295/601) | 54.7 (525/960) | 0.04 | 52.5 (487/927) | 52.5 (333/634) | 0.96 |

| Tobramycin | 33.4 (189/566) | 33.4 (292/874) | 0.96 | 37.1 (343/925) | 26.8 (138/515) | <0.001 |

| Amikacin | 95.8 (588/614) | 98.0 (982/1002) | 0.01 | 97.1 (898/925) | 97.3 (672/691) | 0.96 |

| TMP-SMX | 36.9 (222/601) | 33.4 (319/955) | 0.17 | 31.5 (292/925) | 38.5 (243/631) | 0.005 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 83.9 (468/558) | 83.2 (754/906) | 0.80 | 83.1 (765/921) | 84.2 (457/543) | 0.63 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 60.4 (252/417) | 58.2 (291/500) | 0.53 | 60.4 (460/762) | 61.9 (86/139) | 0.81 |

| Meropenem | 99.6 (272/273) | 100.0 (447/447) | 0.80 | 99.8 (515/516) | 100.0 (204/204) | 0.63 |

| Imipenem | 99.5 (366/368) | 100.0 (517/517) | 0.34 | 99.8 (482/483) | 99.8 (401/402) | 0.56 |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 34.3 (59/172) | 19.5 (15/77) | 0.03 | 33.0 (65/197) | 17.3 (9/52) | 0.04 |

| Gentamicin | 36.9 (62/168) | 37.3 (28/75) | 0.94 | 35.0 (69/197) | 45.7 (21/46) | 0.24 |

| Tobramycin | 28.6 (46/161) | 27.1 (19/70) | 0.75 | 25.0 (49/196) | 45.7 (16/35) | 0.02 |

| Amikacin | 92.9 (158/170) | 97.4 (76/78) | 0.95 | 94.9 (186/196) | 92.3 (48/52) | 0.70 |

| TMP-SMX | 22.0 (37/168) | 16.0 (12/75) | 0.36 | 21.3 (42/197) | 15.2 (7/46) | 0.47 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 29.1 (46/158) | 7.4 (5/68) | <0.001 | 25.0 (49/196) | 6.7 (2/30) | 0.05 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 42.3 (60/142) | 38.0 (19/50) | 0.72 | 39.6 (72/182) | 70.0 (7/10) | 0.12 |

| Meropenem | 100.0 (73/73) | 100.0 (35/35) | 0.99 | 100.0 (83/83) | 100.0 (25/25) | 0.99 |

| Imipenem | 100.0 (105/105) | 100.0 (41/41) | 0.99 | 100.0 (127/127) | 100.0 (19/19) | 0.99 |

Values (except for P values) are the percentages (numbers) of isolates susceptible to each drug.

We report a 4-fold increase in overall incidence and a 2-fold increase in nosocomial incidence of ESBL-E over a 5-year period in Toronto, Canada. Previous Canadian surveillance in 2000 identified 0.3% of E. coli and 0.7% of K. pneumoniae isolates as ESBL producers (14). Between 2007 to 2009, estimated national prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli was reported to be 4.1% and stable over the 3-year study period (23). Concurrently, studies in Calgary have described increasing rates of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae (0.1% to 1.1%) and E. coli (0.3% to 14%) in the past decade (17, 19). This underscores the importance of understanding local epidemiology, particularly for antimicrobial susceptibility, as local geographic changes may not be apparent in larger surveillance studies.

ESBL-E is associated with a delay in administration of active antimicrobial agents (25), a risk factor for mortality due to ESBL-E infection (8). Over the 5-year study, the majority of agents had stable susceptibility profiles. Aminoglycoside susceptibility improved among E. coli, although about one-third of isolates remained resistant to gentamicin and tobramycin. Reduced ciprofloxacin susceptibility was observed in E. coli (12.8%), similar to rates reported in Canada and worldwide (5, 7, 23). However, K. pneumoniae susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (28 to 36%) (17, 26) was significantly higher in other Canadian centers than observed in this study in 2009 (9.0%). More concerning was the frequent occurrence of multiclass resistance among ESBL-E. Use of alternative agents, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, have been assessed (21), but in vitro susceptibility testing is required, as decreasing susceptibility was observed over the course of this study. In patients with severe sepsis where ESBL-E is considered the probable organism, empirical treatment with carbapenems is warranted. However, dependence on carbapenems will increase the selective pressure for carbapenem resistance. Resistance was rare in Toronto in 2009, but several recent case reports suggest that CRE incidence may be increasing (10, 24).

Although for K. pneumoniae there was a trend toward reduced susceptibility among nonnosocomial isolates to ciprofloxacin, TMP-SMX, and nitrofurantoin, there was no difference in the susceptibility to these oral agents in nosocomial and nonnosocomial E. coli isolates. Susceptibility profiles within academic and community institutions were generally indistinguishable. This may be due to the community introduction and spread of CTX-M β-lactamase-producing E. coli in Canada (18–20). The lack of difference between nosocomial and nonnosocomial isolates poses challenges in treatment of severe community-acquired infections in which ESBL-E is a potential pathogen.

There are limitations to this study, as antimicrobial susceptibility testing was based on 2009 CLSI standards with higher cephalosporin breakpoints. Although both extended-spectrum cephalosporin-intermediate and cephalosporin-resistant isolates were confirmed with phenotypic testing in this study, ESBL-E with low-level ceftazidime resistance could have been missed (4). As a result, ESBL-E incidence rates may have been underestimated. Also, given the retrospective nature of the study, nosocomial and nonnosocomial isolates were stratified by a predetermined definition. Without correlation with the clinical history, these isolates are “probable” rather than “confirmed” nosocomial isolates.

Increasing rates of ESBL-E, especially in nonnosocomial patients, presents therapeutic challenges due to low susceptibility to non-β-lactam antimicrobials. In addition, nonnosocomial ESBL-E isolates were associated with lower susceptibility to the limited oral agents remaining for ESBL-E, particularly K. pneumoniae. Fluoroquinolones should be avoided in patients with suspicion for an ESBL-E infection due to the very low rates of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin observed in both E. coli and K. pneumoniae.

(Preliminary results were presented at the 22nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in London, United Kingdom.)

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI M100-S19. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coque TM, et al. 2008. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grundmann H, et al. 2010. Carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: conclusions from a meeting of national experts. Euro Surveill. 15:19711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawser SP, Badal RE, Bouchillon SK, Hoban DJ, Hsueh PR. 2010. Comparison of CLSI 2009, CLSI 2010 and EUCAST cephalosporin clinical breakpoints in recent clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca from the SMART Global Surveillance Study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:293–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoban DJ, Bouchillon SK, Hawser SP, Badal RE. 2010. Trends in the frequency of multiple drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and their susceptibility to ertapenem, imipenem, and other antimicrobial agents: data from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends 2002 to 2007. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 66:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoban DJ, et al. 2010. Susceptibility of Gram-negative pathogens isolated from patients with complicated intraabdominal infections in the United States, 2007–2008: results of the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3031–3034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoban DJ, Nicolle LE, Hawser S, Bouchillon S, Badal R. 2011. Antimicrobial susceptibility of global inpatient urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli: results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) program: 2009–2010. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70:507–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hyle EP, et al. 2005. Impact of inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy on mortality in infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: variability by site of infection. Arch. Intern. Med. 165:1375–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumarasamy KK, et al. 2010. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:597–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kus JV, et al. 2011. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1: local acquisition in Ontario, Canada, and challenges in detection. CMAJ 183:1257–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lautenbach E, Patel JB, Bilker WB, Edelstein PH, Fishman NO. 2001. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: risk factors for infection and impact of resistance on outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1162–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lowe C, Katz K, McGeer A, Muller MP, Toronto Working Group ESBL 2012. Disparity in infection control practices for multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Am. J. Infect. Control. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mataseje LF, et al. 2011. Plasmid comparison and molecular analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae harbouring bla(KPC) from New York City and Toronto. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1273–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mulvey MR, et al. 2004. Ambler class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in Canadian hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1204–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. 2009. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. 2005. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:657–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peirano G, Hung King Sang J, Pitondo-Silva A, Laupland KB, Pitout JD. 2012. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae over a 10 year period in Calgary, Canada. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. doi:10.1093/jac/dks026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peirano G, et al. 2010. High prevalence of ST131 isolates producing CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Canada. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1327–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peirano G, van der Bij AK, Gregson DB, Pitout JD. 2012. Molecular epidemiology over an 11-year period (2000 to 2010) of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in a centralized Canadian region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:294–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pitout JD, Hanson ND, Church DL, Laupland KB. 2004. Population-based laboratory surveillance for Escherichia coli-producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: importance of community isolates with blaCTX-M genes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1736–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodriguez-Bano J, et al. 2012. Beta-lactam/beta-lactam inhibitor combinations for the treatment of bacteremia due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: a post hoc analysis of prospective cohorts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simner PJ, et al. 2011. Prevalence and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: results of the CANWARD 2007–2009 study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69:326–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tijet N, et al. 2011. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, Ontario, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:306–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tumbarello M, et al. 2007. Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: importance of inadequate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1987–1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walkty A, et al. 2011. In vitro activity of ceftobiprole against frequently encountered aerobic and facultative Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens: results of the CANWARD 2007–2009 study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69:348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]