Abstract

The characterization of a broad representative sample of ST131 Escherichia coli isolates from different origins and settings (1991 to 2010) revealed that this clonal group has likely diversified recently and that the expansion of particular variants has probably been favored by the capture of diverse, multidrug-resistant IncFII plasmids (pC15-1a, pEK499, pKF3-140-like). The low ability to adhere and to grow as biofilm that was detected in this study suggests unknown mechanisms for the persistence of this clonal group which need to be further explored.

TEXT

The B2-ST131 Escherichia coli clone is currently spread worldwide among humans, but it is also being frequently recovered from livestock and companion animals (28, 29). Variants showing highly similar pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) types but variable content of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes seem to be locally amplified in different areas (1, 4, 7, 22, 33). The acquisition of a diversity of genes encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs; mostly CTX-M-15), carbapenemases (VIM, NDM, KPC), cephamycinases (CMY), methylases (AmrA), quinolone-modifying enzymes (QNR), and/or virulence factors (VFs) seems to have contributed to the successful spread and persistence of this clonal group (5, 29, 32, 33). Specific VFs (fyuA, papC, papG, cnf1, or hlyA) potentially associated with in vitro biofilm production on abiotic surfaces have been identified in ST131 strains (10, 24); however, this feature has been tested only in a reduced number of strains (2). We aim to analyze the diversity of B2-ST131 E. coli isolates from different geographic origins and settings during the last decades (1991 to 2010) and to assess the ability of isolates representing particular lineages to adhere to and form biofilm on abiotic surfaces.

We studied 32 B2-ST131 E. coli isolates (31 ST131 and one ST1035, corresponding to a single-locus variant [SLV] of ST131) obtained between 1991 and 2010, including ST131 strains involved in nosocomial and community outbreaks but also isolates from healthy volunteers, animals, and environmental samples from different geographic areas and producing (18 CTX-M-15, 1 CTX-M-1, 1 CTX-M-3, 1 TEM-4, 1 TEM-24) and nonproducing ESBLs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Isolates included in this studya

| Country | No. of isolates | ST | Yr(s) obtained | Origin(s) (no. of isolates) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 9 | 131 | 2001–2010 | H (6), F (1), E (2) | 21, Novais et al., submitted for publicationb |

| Spain | 6 | 131 | 1991–2008 | H (5), C (1) | 5, 25 |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 131 | ND | H (3) | 16 |

| United States of America | 3 | 131 | 2008 | A (3) | 14 |

| France | 3 | 131 | 2006 | F (3) | 18 |

| Norway | 2 | 131 | 2003 | H (2) | 23 |

| Czech Republic | 2 | 131 | 2006 | H (2) | 11 |

| South Korea | 2 | 131 | 2006–2007 | C (2) | 17 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 131 | 2005 | H (1) | 5 |

| Croatia | 1 | 1035 | 2005 | H (1) | 20 |

ST, sequence type; H, hospitalized humans (obtained from representative outbreaks); C, community-acquired infections (obtained from representative outbreaks); F, healthy humans (feces); A, animals (2 animal infections, 1 fecal isolate); E, environment (marine waters); ND, not determined.

Â. Novais, C. Rodrigues, R. Branquinho, P. Antunes, F. Grosso, L. Boaventura, G. Ribeiro, and L. Peixe, submitted for publication.

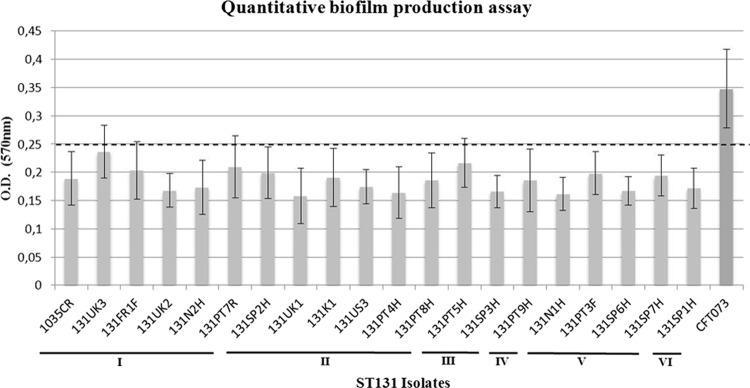

The relationship among isolates that was established by PFGE, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), identification of serogroups, and the presence of 38 genes encoding VFs presumptively associated with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) strains (5, 13, 19) indicated a high similarity in PFGE profiles (69.8% identity) among the ST131 isolates (all but one identified as O25) and a high virulence score (median, 11; range, 7 to 15), with most of the isolates (n = 25, 78.1%) being considered ExPEC (66.7% of them from urinary tract infections [UTIs] and 33.3% from other ExPEC infections). Isolates were grouped in six clusters (showing 81.1% to 90.9% identity) arbitrarily designated I to VI (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

XbaI profiles were analyzed by InfoQuest FP version 5.4 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and the percentage similarity was calculated by applying the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) algorithm based on the Dice coefficient (1.0% band tolerance; 1.0% optimization). (a) Isolates considered ExPEC are underlined. (b) H, hospitalized humans; C, community-acquired infections; F, healthy humans; A, animal; E, environment (marine waters). (c) Plasmids encoding the ESBLs identified in each isolate are shown in bold. FII plasmids were identified using the FAB formula (FII, FIA, FIB), as proposed previously (31). Antibiotic susceptibility testing was done by Etest and the disk diffusion method following CLSI guidelines (3) (d) This isolate coproduces SHV-12. Asc. Liq., ascistic liquid. (e) fimH, type 1 fimbriae; papA, P fimbriae major subunit, pyelonephritis associated; papC, P fimbriae assembly; papEF, P fimbriae minor tip pilins; papG allele II, papG variant, pyelonephritis associated; papG allele III, P fimbriae adhesin, cystitis associated; afa/draBC, Dr antigen-specific adhesin; iha, iron-regulated gene homologue adhesin; sat, secreted autotransporter toxin; tsh, serine protease autotransporter; fyuA, yersiniabactin receptor; iutA, ferric aerobactin receptor; iroN, catecholate siderophore receptor; kpsMTII, group II capsular polysaccharide; kpsMTII K1, variant K1; kpsMTII K5, variant K5; traT, serum survival associated; iss, increased serum survival; ibeA, invasion of brain endothelium; usp, uropathogen-specific protein; ompT, outer membrane protease; malX, pathogenicity-associated island marker. PT, Portugal; SP, Spain; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States of America; FR, France; NW, Norway; RC, Czech Republic; KO, South Korea; SW, Switzerland; CR, Croatia.

Most of the isolates belonging to clusters I to IV and VI exhibited a common profile of virulence genes (fimH, iha, traT, usp, sat, malX, fyuA, iutA, ompT) (n = 22, 69%) and also frequently kpsMTII-K5 (n = 23, 71.9%), as previously observed (4, 15, 26). Variations to this profile include the presence of K1 antigen (n = 8; mostly in cluster II), papEF (n = 5; mostly in cluster I) and occasionally other pap alleles, ibeA (n = 4; all from cluster V), or afa/draBC (n = 3; from clusters II and VI). Our results and the high prevalence of each of these 11 virulence genes among ST131 and its SLV isolates in different surveys (over 60%) suggest clonal diversification from a common ancestor by loss (kpsMTII-K5) or acquisition (K1, pap, afa/draBC, ibeA) of specific virulence traits (Fig. 1) (1, 6, 17), which would have originated variants with the ability to spread and evolve in different hosts and settings (1, 4, 17). ST131 variants containing afa/draBC, a Dr antigen-specific adhesin, were identified only in isolates (n = 3) from Spain and the United Kingdom, where they seem to be particularly frequent (over 25%) with respect to their presence in other countries (6.3 to 10%) (1, 4, 13, 15, 17). Interestingly, ST131 variants containing ibeA (n = 4; P < 0.05, as determined by the Fisher exact test), a VF previously associated with avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) and responsible for neonatal meningitis in humans (9, 22), corresponded to early ST131 isolates (1991 to 2003) grouped in a separate branch (cluster V; 81.1% identity). These isolates seem to be able to exhibit a diversity of genetic backgrounds (Fig. 1) (see below) (4, 22).

Plasmid analysis (number, size, and replicon typing) inferred by S1-PFGE, PCR-based replicon typing, and identification of IncFII plasmids by using the recently proposed FAB formula (based on FII, FIA, and FIB sequences) (www.pubmlst.org/plasmid/) (5, 31) revealed a high diversity of IncF plasmids identified in all ST131 isolates and the variable presence of the IncN, IncA/C, and IncI1 plasmid types, which seem to be enriching this clonal group, as recently reported (26).

IncFII plasmids from CTX-M-15 producers (clusters I to IV and VI; mostly from hospitalized patients) carried an FII replicon previously designated allele F2 (n = 7), resembling pC15-1a (F2:A−:B−; GenBank accession number AY458016), or FII plus FIA (n = 9), resembling pEK499 (F2:A1:B−; GenBank accession number EU935739) (Fig. 1) (31, 32). These variants constitute two of the most widespread CTX-M-15-encoding IncFII variants described worldwide (5, 32). IncFII plasmids from non-CTX-M-15 ST131 producers (clusters I, II, and III; mostly from extrahospital samples) contained FII, FIA, and FIB replicons (F1:A2:B2; n = 9), identical to the multidrug-resistant plasmid pKF3-140 (GenBank accession number FJ876827), which was primarily identified in a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain from hospitalized patients in China (2002 to 2006) (34) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, this configuration was not found among international CTX-M-15 producers characterized in previous studies (5, 8, 27). IncFII plasmids from non-CTX-M-15 ST131 isolates from cluster V harbored FII allele F29, which is homologous to that of the pUTI89 virulence plasmid (GenBank accession number CP000244), and all but one isolate also contained FIB (F29:A−:B10; n = 3). Most of these isolates also carried non-IncFII plasmids (IncA/C, IncI1, IncN) encoding ESBLs other than CTX-M-15 which seem to be captured by particular ST131 backgrounds (1, 4, 22). Other configurations were also sporadically detected (F2:A1:B1, F24:A1:B2, F1:A−:B2, F1:A2:B−) and might have resulted from recombinatorial events occurring among circulating IncFII plasmids, as previously suggested (5, 27).

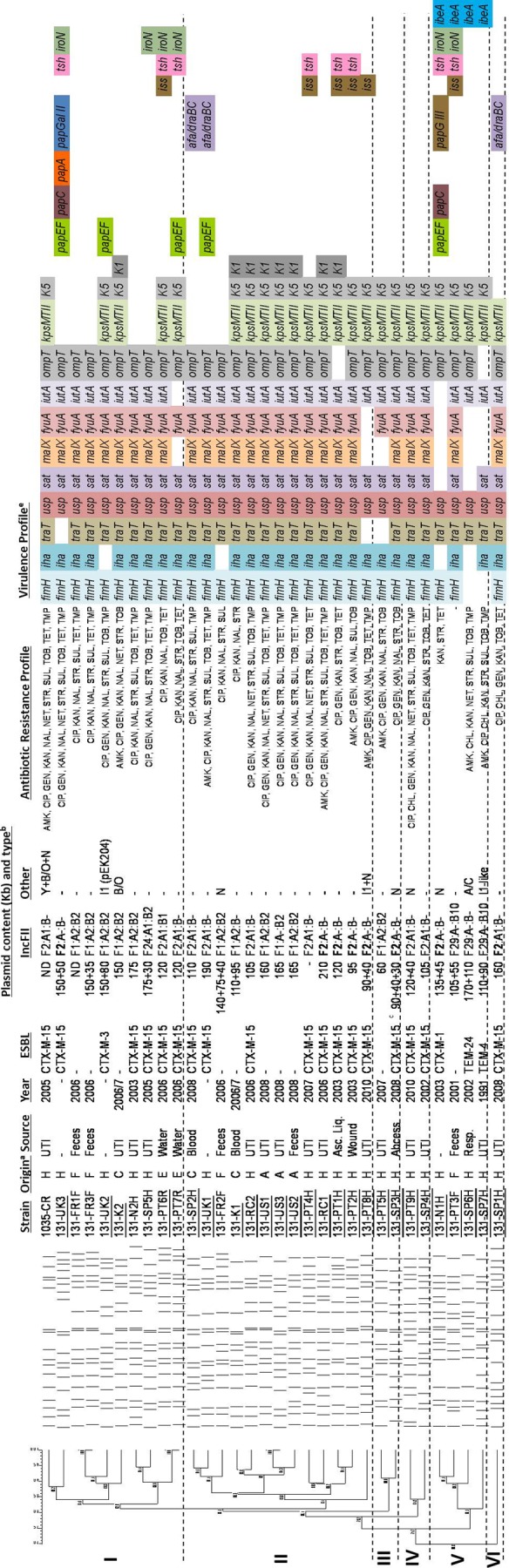

The ability of representative ST131 E. coli isolates (variable PFGE, virulence, and plasmid profiles) to adhere in vitro to abiotic surfaces was investigated by a modified quantitative biofilm production assay, adapted from previous studies (7, 12), and confirmed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). The E. coli strain CFT073 and the culture medium were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Assays were performed in triplicate and repeated 4 times. The cutoff optical density (ODc) was defined as three standard deviations above the mean OD of the negative control (culture medium), and strains were classified as nonadherent (OD ≤ ODc), weakly adherent (ODc < OD ≤ 2 × ODc), moderately adherent (2 × ODc < OD ≤ 4 × ODc), or strongly adherent (4 × ODc < OD). Despite the presence of genes presumptively implicated in adhesion to abiotic surfaces and/or biofilm formation (fimH, pap alleles, afa/draBC, fyuA, iutA, or ibeA), all strains tested (n = 20) were classified as weakly adherent, with OD values ranging from 0.158 and 0.237 (Fig. 2). Although adherent bacteria and clusters were sometimes observed in the micrographs, none of the obtained images definitely showed a mature biofilm (data not shown). In contrast with Clermont et al. (2), our results seem to suggest that ST131 isolates with variable virulence profiles and from different origins exhibited a low propensity to adhere and no ability to develop a mature biofilm on abiotic surfaces, at least under the experimental conditions. Apart from biofilm formation abilities, it cannot be discarded that certain predominant VFs, such as malX or usp, might have a role in intestinal colonization (as malX or usp) or eventually mediate an antibiofilm effect against other competitors (as kpsMTII), conferring an advantage within the same bacterial communities, possibilities which deserve to be further explored (30).

Fig 2.

The vertical axis represents the median optical density (OD), determined at 570 nm, of multiple replicas of each isolate. The horizontal axis includes the representative ST131 isolates tested and the assigned clusters (I to VI). E. coli CFT073 was used as a positive control. The horizontal dotted line represents the cutoff value between weakly adherent (light gray) and moderately adherent (dark gray) strains. PT, Portugal; SP, Spain; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States of America; FR, France; NW, Norway; RC, Czech Republic; KO, South Korea; SW, Switzerland; CR, Croatia.

In summary, this study shows that worldwide disseminated ST131 isolates from different origins and settings (ca. 70% identity; common virulence profiles) have recently been diversified and that particular widespread lineages might have been selected and amplified after acquisition of diverse and specific multidrug-resistant IncFII plasmids. None of the isolates included in this study was able to form biofilm in the tested conditions, highlighting that additional studies are necessary to further investigate the reasons favoring the expansion and persistence of the ST131 clonal group. This work contrasts with previous studies focused on the characterization of locally predominant ST131 isolates, and despite the limitations imposed by the sample size that may be overcome by an increased and more balanced number of isolates from different origins and periods of time, it allows us to gain insights about the global ST131 population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a Marie Curie Intra European Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Programme (reference no. PIEF-GA-2009-255512) and by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through grant no. PEst-C/EQB/LA0006/2011.

We thank (in alphabetical order) Rafael Cantón (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Spain), Marek Gniadkowski (National Medicines Institute, Poland), James R. Johnson (Minneapolis VA Medical Center, USA), So Hyun Kim (Asian Bacterial Bank of the Asia Pacific Foundation for Infectious Diseases), Marie-Hélène Nicolas-Chanoine (Hôpital Beaujon, France), Arnfinn Sundsfjord (Department of Medical Biology, University of Tromsø, Norway), and Neil Woodford (Antibiotic Resistance Monitoring & Reference Laboratory, Health Protection Agency, United Kingdom) for the strain gifts. We extend our gratitude to Patrice Nordman (Service de Bactériologie-Virologie, Hôpital de Bicêtre, Paris, France) and Johann Pitout (Division of Microbiology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada), who provided us with the CTX-M-15-producing ST131 isolates also included in a previous publication (5). We are also grateful to Maria Giovanna Martinotti for the gift of E. coli CFT073 and Carla Rodrigues for statistical analysis support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Blanco J, et al. 2011. National survey of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections reveals the spread of drug-resistant clonal groups O25b:H4-B2-ST131, O15:H1-D-ST393 and CGA-D-ST69 with high virulence gene content in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2011–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clermont O, et al. 2008. The CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli diffusing clone belongs to a highly virulent B2 phylogenetic subgroup. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1024–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2011. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 21st informational supplement. CLSI M100-S21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coelho A, et al. 2011. Spread of Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131 producing CTX-M-15 and SHV-12 with high virulence gene content in Barcelona (Spain). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coque TM, et al. 2008. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Croxall G, et al. 2011. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from a regional cohort of elderly patients highlights the prevalence of ST131 strains with increased antimicrobial resistance in both community and hospital care settings. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2501–2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Donelli G, et al. 2004. Sex pheromone response, clumping, and slime production in enterococcal strains isolated from occluded biliary stents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3419–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doumith M, Dhanji H, Ellington MJ, Hawkey P, Woodford N. 2012. Characterization of plasmids encoding extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and their addiction systems circulating among Escherichia coli clinical isolates in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:878–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Germon P, et al. 2005. ibeA, a virulence factor of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 151:1179–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hancock V, Ferrieres L, Klemm P. 2008. The ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli in human urine. Microbiology 154:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hrabak J, et al. 2009. International clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli with extended-spectrum β-lactamases in a Czech hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3353–3357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingle DJ, et al. 2011. Biofilm formation by and thermal niche and virulence characteristics of Escherichia spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2695–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson JR, et al. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson JR, Miller S, Johnston B, Clabots C, Debroy C. 2009. Sharing of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 and other multidrug-resistant and urovirulent E. coli strains among dogs and cats within a household. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3721–3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karisik E, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2008. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli with CTX-M-15 and other extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:54–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lau SH, et al. 2008. UK epidemic Escherichia coli strains A-E, with CTX-M-15 beta-lactamase, all belong to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1241–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee MY, et al. 2010. Dissemination of ST131 and ST393 community-onset, ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli clones causing urinary tract infections in Korea. J. Infect. 60:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leflon-Guibout V, et al. 2008. Absence of CTX-M enzymes but high prevalence of clones, including clone ST131, among fecal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy subjects living in the area of Paris, France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3900–3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li D, et al. 2010. A multiplex PCR method to detect 14 Escherichia coli serogroups associated with urinary tract infections. J. Microbiol. Methods 82:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Literacka E, et al. 2009. blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia coli strains from Croatian Hospitals are located in new (blaCTX-M-3a) and widely spread (blaCTX-M-3a and blaCTX-M-15) genetic structures. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1630–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Machado E, et al. 2006. Dissemination in Portugal of CTX-M-15-, OXA-1-, and TEM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains containing the aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene, which encodes an aminoglycoside- and fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3220–3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mora A, et al. 2010. Recent emergence of clonal group O25b:K1:H4-B2-ST131 ibeA strains among Escherichia coli poultry isolates, including CTX-M-9-producing strains, and comparison with clinical human isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6991–6997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naseer U, et al. 2009. Molecular characterization of CTX-M-15-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli reveals the spread of multidrug-resistant ST131 (O25:H4) and ST964 (O102:H6) strains in Norway. APMIS 117:526–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naves P, et al. 2008. Correlation between virulence factors and in vitro biofilm formation by Escherichia coli strains. Microb. Pathog. 45:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novais A, et al. 2010. International spread and persistence of TEM-24 is caused by the confluence of highly penetrating Enterobacteriaceae clones and an IncA/C2 plasmid containing Tn1696::Tn1 and IS5075-Tn21. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:825–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Novais A, et al. 2012. The contribution of IncFII and broad-host IncA/C and IncN plasmids to the local expansion and diversification of B2-Escherichia coli ST131 carrying blaCTXM-15 and qnrS1 genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2763–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Partridge SR, Zong Z, Iredell JR. 2011. Recombination in IS26 and Tn2 in the evolution of multiresistance regions carrying blaCTX-M-15 on conjugative IncF plasmids from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4971–4978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Platell JL, Johnson JR, Cobbold RN, Trott DJ. 2011. Multidrug-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli of sequence type ST131 in animals and foods. Vet. Microbiol. 153:99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valle J, et al. 2006. Broad-spectrum biofilm inhibition by a secreted bacterial polysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12558–12563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villa L, Garcia-Fernandez A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. 2010. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2518–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woodford N, et al. 2009. Complete nucleotide sequences of plasmids pEK204, pEK499, and pEK516, encoding CTX-M enzymes in three major Escherichia coli lineages from the United Kingdom, all belonging to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4472–4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. 2011. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:736–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao F, et al. 2010. Sequencing and genetic variation of multidrug resistance plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS One 5:e10141 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]