Abstract

Analyses of the breadth and specificity of virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses associated with control of HIV have largely relied on measurement of cytokine secretion by effector T cells. These have resulted in the identification of HIV elite controllers with low or absent responses in which non-T-cell mechanisms of control have been suggested. However, successful control of HIV infection may be associated with central memory T cells, which have not been consistently examined in these individuals. Gag-specific T cells were characterized using a peptide-based cultured enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISpot). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV elite controllers (n = 10), progressors (n = 12), and antiretroviral-treated individuals (n = 9) were cultured with overlapping peptides for 12 days. Specificity was assessed by tetramer staining, functional features of expanded cells were assessed by cytokine secretion, and virus inhibition and phenotypic characteristics were assessed by cell sorting and coculture assays. After peptide stimulation, elite controllers showed a greater number of previously undetectable (new) responses compared to progressors (P = 0.0008). These responses were highly polyfunctional, with 64.5% of responses having 3 to 5 functions. Expandable epitope-specific CD8+ T cells from elite controllers had strong virus inhibitory capacity and predominantly displayed a central memory phenotype. These data indicate that elite controllers with minimal T cell responses harbor a highly functional, broadly directed central memory T cell population that is capable of suppressing HIV in vitro. Comprehensive examination of this cell population could provide insight into the immune responses associated with successful containment of viremia.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) elite controllers (EC) spontaneously control viral replication to levels below the limit of detection by standard clinical assays without the need for antiretroviral therapy (ART). Although primarily defined by plasma virus load, most maintain high absolute CD4+ T cell counts, making them an excellent model of natural immunity to HIV (13, 29). As such, they have been the focus of extensive investigations aimed at identifying the immunologic correlates of protection that result in this remarkable outcome (3, 48).

Of the many adaptive immune responses that have been studied as correlates of protection in HIV infection, an overwhelming majority of data suggests that HIV-specific CD8+ T cells play a critical role in virus containment. The contribution of CD8+ T cells was initially demonstrated in animal models of AIDS virus infection in which a temporal relationship between the decline of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) load and the emergence of SIV-specific CD8+ T cells was demonstrated in rhesus macaques (28); additional indirect evidence comes from the identification of CD8+ T cell immune selection pressure on the virus, the emergence of escape mutants (1, 18, 27), and the genetic association between HLA class I polymorphisms and disease outcome (9, 36, 38, 39).

Despite these data suggesting a prominent role for virus-specific CD8+ T cells in controlling HIV, the correlates of immune protection in these individuals remain controversial. Indeed, there has been marked heterogeneity in studies of correlates of protection in persons who control HIV spontaneously (25, 38, 42). Studies have shown associations between polyfunctionality of CD8+ T cell responses and viral control (2), whereas others suggest that the ability to proliferate due in response to antigen exposure and loading of lytic granules are key parameters (34, 35). While some studies have demonstrated high frequency of virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses and HIV suppression capacity (11, 23, 41), others have demonstrated low or completely undetectable CD8+ T cell responses (weak responders or “non-T-cell controllers”) (16) and minimal detectable HIV suppression capacity despite harboring replication-competent viruses (38, 42). These data suggest that CD8+ T cell responses and function, at least as measured by ex vivo assays, are not a requirement for spontaneous HIV control and that other host restriction mechanisms must contribute to durable containment of HIV (10, 21, 33). Furthermore, it has led to the hypothesis that effective T cell responses are not necessary for long-term HIV control (16).

Ex vivo gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays (ELISpot) and intracellular cytokine staining assays commonly used to assess CD8+ T cell responses detect only a subset of cells capable of immediate secretion of IFN-γ upon stimulation. These populations are mainly comprised of effector, terminal effector, and partially exhausted cells, most of which are ineffective at sustaining virus inhibition (12). CD8+ T cells exist in a continuum of differentiation states ranging from naïve to the terminally differentiated stage (12, 24). The fate of the differentiation pathways is predisposed by the sequence of the infecting virus, immunological escape due to viral mutations, and antigen load (8, 22, 44, 49).

In situations in which plasma viremia is successfully and durably controlled to exceedingly low levels, central memory T cell populations might be expected to undergo less stimulation to effector memory cells, which would result in a lower frequency of effector memory responses. Hence, one could hypothesize that, because of the very low plasma viral loads in HIV elite controllers, the true breadth of responses to HIV in this situation of viral containment has not been fully evaluated. Moreover, although some studies have used in vitro stimulation and expansion to measure the cytotoxic capacity of memory cells (35) and maintenance of HIV-specific effector memory T cells responses has been correlated with viral control (20), characteristics of central memory cell populations in elite controllers have not been reported.

In this study, we sought to interrogate HIV-specific CD8+ central memory T cells among elite controllers with absent or low ex vivo T cell responses (weak responders) and to characterize their specificity, functionality, and phenotypic characteristics. Our results indicate that these individuals harbor a highly functional, broadly directed central memory T cell population that is capable of suppressing HIV in vitro and provide insights into the T cell responses that ultimately result in successful durable containment of plasma viremia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

HIV-infected individuals and HIV-seronegative controls were recruited from outpatient clinics at Massachusetts General Hospital and affiliated Boston area hospitals. The respective institutional review boards approved this study, and all subjects gave written informed consent. Elite controllers were defined as having plasma HIV RNA levels below the limit of detection for the respective available clinical assay (e.g., <75 RNA copies/ml by branched DNA [bDNA] or <50 copies by PCR) in the absence of antiretroviral therapy on at least three determinations over at least a year of follow-up. Previously identified elite controllers with known low breadth of Gag-specific T cell responses measured by an IFN-γ ELISpot assay were selected (38); on average, they had 5 Gag responses (range, 0 to 12). Chronic progressors (CP) included in the study had a median virus load of 29,231 copies/ml (interquartile range [IQR], 7,885 to 122,076 copies/ml) in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Chronic treated individuals had HIV RNA levels below the limit of detection for the respective available clinical assay (e.g., <75 RNA copies/ml by bDNA or <50 copies by PCR) while receiving of combination antiretroviral therapy; one chronic treated individual had a viral blip of 160 copies/ml at the time of the sample collection. All subjects selected for this study were selected to have absolute CD4+ T cell counts of >400 cells/mm3. Among chronic progressors and treated individuals with high absolute CD4+ T cell counts, selection was also made on the basis of known Gag-specific T cell responses; on average, they had 8 responses (range, 4 to 15). High-resolution HLA class I typing was performed in all patients by sequence-specific primer PCR as previously described (38).

IFN-γ ELISpot.

IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays (ELISpot) were performed as described previously (45) using a final concentration of 100 ng/ml (20 ng in a 200-μl volume) of 66 overlapping peptides (OLPs; each peptide averaged 18 amino acids in length and overlapped by 10 amino acids) spanning the entire Gag protein. Input cells ranged from 50,000 to 100,000 per well depending on cell availability. The number of specific spot-forming cells (SFC) was calculated by subtracting the number of spots in the negative-control wells from the number of spots in each experimental well. Responses were regarded as positive if they had at least three times the mean number of SFC in the three negative-control wells. Positive responses also had to be at least 50 SFC/106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). The magnitude of the epitope-specific response was reported as the number of SFC per million cells.

Cultured IFN-γ ELISpot.

Gag-stimulated and unstimulated cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 12 days in RPMI medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (R10 medium) and supplemented with 50 units/ml of recombinant human interleukin 2 (IL-2) (R10/50 medium). Serial peptide dilutions ranging from 10 μg/ml to 10 ng/ml were tested in 5 subjects (3 elite controllers and 2 chronic progressors) to define the concentration at which pooled Gag OLPs stimulated the greatest number of responses with the lowest background. A concentration of 100 ng/ml (the final concentration of each peptide within the pool) was selected for these experiments. Fresh R10/50 medium was added at day 3, day 7, and day 10 as needed. On day 12, cells were washed three times with fresh R10 medium and rested at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight in fresh R10 medium. They were then retested against all 66 Gag-OLPs in an ELISpot assay as described above.

Tetramer staining.

PBMC were first stained with the blue viability dye (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) for 15 min, followed by tetramer staining for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then surface stained with the following human antibody panel: CD3, CD8, CD4, CD14, CD19, and CD56 (BD Pharmingen) (37). Samples were acquired on the BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences), and data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 9.0.2.

Intracellular cytokine staining.

PBMC were expanded for 12 days, rested overnight as described above, and then restimulated with Gag OLPs at a 20-ng/ml final concentration and anti-CD28/CD49d antibodies (BD Biosciences) for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Anti-CD107a antibody was also added at the beginning of the stimulation period to measure degranulation. After 1 h, 10 ng/ml of brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and the cells were incubated for another 5 h. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed as previously described (2). Briefly, cells were first stained with dead-cell dye for 10 min and then washed and surface stained with anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -CD14, -CD19, and -CD56. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution and stained with cytokine-specific antibodies against IFN-γ and IL-2, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and MIP-1β (all purchased from BD Biosciences). Following staining, the cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were acquired on the BD LSRFortessa cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed with the FlowJo software package (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Viral inhibition assay.

The ability of CD8+ T cells to inhibit virus replication in autologous primary CD4+ T cells was assessed by measuring p24 antigen production, as described elsewhere (11). Primary CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated on the RoboSep (Stemcell Technologies) using the EasySep human CD8-positive selection kit (catalog number 18053). The enriched CD8+ T cells were cultured for 3 days in R10 medium for use as the ex vivo CD8+ effector condition. The CD4+ T cells were stimulated with CD3-/CD8-bispecific antibody and infected at day 3 with the NL4-3 lab-adapted HIV strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 for 4 h at 37°C. Virally infected cells were then washed and incubated in the absence or presence of effector cells at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 1:1. The cultures were fed at regular intervals by removing and replacing one-half of the culture supernatant with fresh medium. Supernatants were cryopreserved for later p24 antigen quantification by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). Log inhibition values were calculated by subtracting log10 p24 values with CD8+ T cells from log10 p24 values without CD8+ T cells at day 7.

Column enrichment of tetramer-specific T cells.

A total of 1 × 107 PBMC were incubated with 5 μl phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled B*57 IW9 and B*57 KF11 tetramers for 45 min at room temperature (22°C), followed by 20 μl anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were passed over an LS column, and the flowthrough fraction was discarded. The column was then removed from the magnetic field, and the retained target cells were flushed out as positively selected cells. To further enrich the antigen-specific cells, positively selected cells were passed over MS columns three more times. Enrichment of tetramer-positive cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

Isolation of phenotypically defined CD8+ memory subsets.

PBMC were enriched for CD8+ T cells by negative selection using the CD8+ T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). Enriched CD8+ T cells were stained with the following commercial cytokine antibodies (all from BD): CD45RA fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD27 PE, CD4 alexa700, CD14 pacific blue, CD19 pacific blue, and CD56 pacific blue. Memory CD8+ T cell subsets in each individual were identified using the cell surface reagents listed above and isolated by sorting samples on a 20-parameter BD FACSAria.

Statistical analyses.

Spearman rank correlation and Mann-Whitney tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0b. All tests were two-tailed, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro expansion results in the detection of new Gag-specific T cell responses.

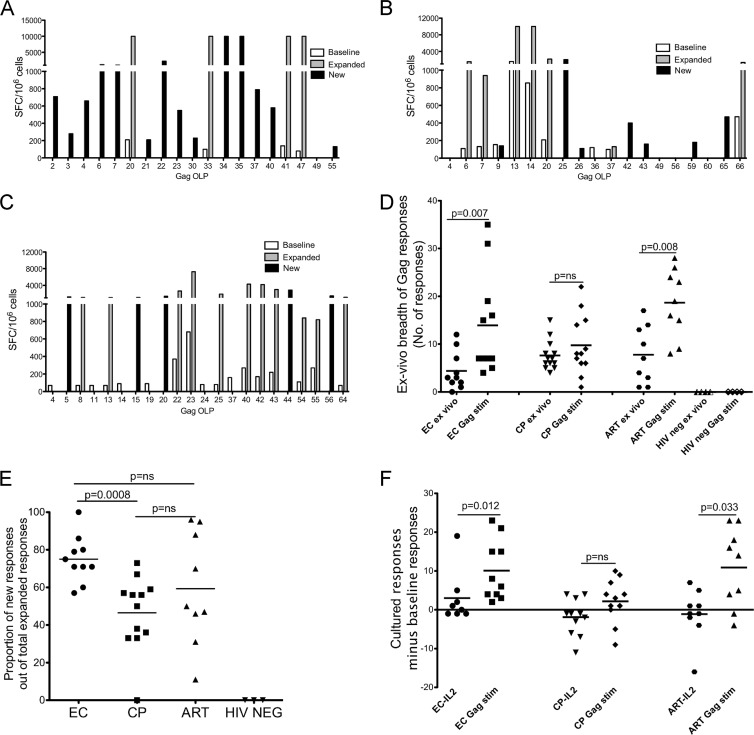

A total of 31 HIV-infected individuals and 4 HIV-seronegative controls were studied. Infected individuals included 10 elite controllers (EC), 12 chronic progressors (CP), and 9 antiretroviral therapy-treated (ART-treated) individuals. Characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. HIV-specific T cell responses were measured ex vivo following 12 days of culture stimulation using a panel of 66 overlapping HIV Gag peptides (Gag OLPs) in an IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Representative results for one elite controller (Fig. 1A), one chronic progressor (Fig. 1B), and one person on suppressive ART (Fig. 1C) show ex vivo responses at baseline (open bars), expanded but detectable responses at baseline (gray bars), and new responses that emerged after cultured stimulation (black bars). The greatest numbers of new responses were detected among elite controllers: expansion of HIV-specific T cells resulted in a significantly higher breadth of responses compared to the baseline in elite controllers (P = 0.007) and in ART-treated individuals (P = 0.008) but not in CP (P = 0.38) (Fig. 1D). Since in vitro expansion of HIV-specific T cells is a more sensitive method for detecting previously unrecognized responses, we compared new responses between elite controllers, CP, and ART-treated individuals. The proportion of new responses out of the total number of expanded responses was significantly higher in elite controllers than in CP (P = 0.0008), but the comparison did not reach statistical significance between ART-treated persons and progressors (P = 0.2) (Fig. 1E). Since IL-2 added to the culture can result in nonspecific expansion of T cells, we compared the numbers of new responses in IL-2-only cultures and found no statistical difference between the three groups (P = 0.2) (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, up to 80% (n = 17) of chronic progressors and ART-treated individuals had a net loss of baseline responses in IL-2-stimulated cultures, compared to only 20% (n = 2) among elite controllers (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these data suggest that among elite controllers with minimal or no measurable ex vivo T cell responses, expansion of Gag-specific responses is significantly higher than that in chronic progressors and that expansion consists mainly of previously unrecognized (new) HIV-specific responses.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Values for each participant type |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controllers | Progressors | ART treated | |

| Gender (no. [%]) | |||

| Male | 7 (70) | 10 (83) | 7 (77) |

| Female | 3 (30) | 2 (17) | 2 (23) |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Median | 51 | 50 | 46 |

| Interquartile range | 44–58 | 34–52 | 42–51 |

| No. of CD4+ T cells/mm3 | |||

| Median | 1,012 | 559 | 600 |

| Interquartile range | 787–1,213 | 429–584 | 508–728 |

| No. of HIV-1 copies/ml | |||

| Median | 49 | 29,231 | 49 |

| Interquartile range | 49–49 | 7,885–122,076 | 49–49 |

Fig 1.

Breadth and magnitude of expandable HIV Gag-specific T cell responses. IFN-γ ELISpot data for one representative elite controller (A), chronic progressor (B), and ART-treated person (C) before and after 12 days of stimulation. (D) Ex vivo and Gag-stimulated breadths of responses are shown. (E and F) Proportions of new responses in cultures stimulated with Gag OLP together with IL-2 (E) and IL-2 alone (F). For all panels, the median numbers for each group are indicated as horizontal black bars. Underlined P values were calculated using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant.

Gag stimulation and viral infection expand HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses.

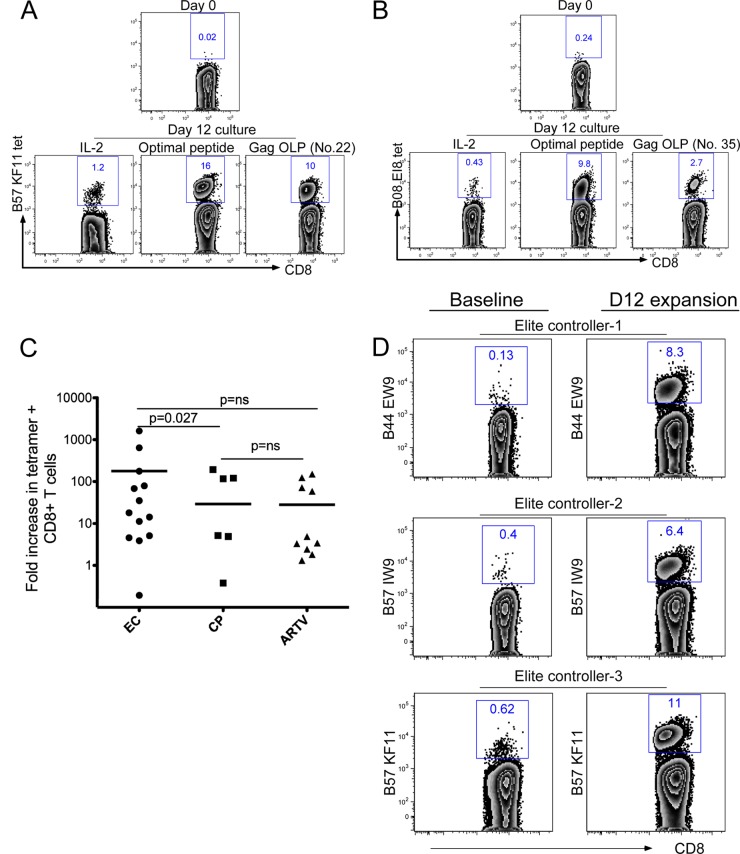

Stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Gag OLPs can result in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell expansion. Considering the strong evidence supporting a specific role for CD8+ T cell responses in long-term viral control, we focused on characterizing low-frequency CD8+ T cell responses. For each donor, at least four Gag OLP sequences that induced a new response were examined for the presence of a known optimal epitope sequence restricted by the class I HLA allele of the responding donor. Tetramers folded with identified epitopes were then used to stain donor cells before and after in vitro expansion. For example, an HLA-B*57/B*08-positive elite controller with strong new responses to Gag OLP number 22 and Gag OLP number 35 (Fig. 1A), which contain B*57 KF11 and B*08 EI8 sequences, respectively, was examined for the expansion of CD8+ T cells restricted by these epitopes. CD8+ T cells specific for B*57 KF11 were expanded from less than 0.02% ex vivo to greater than 10% after 12 days of culture stimulation with a KF11 peptide (Fig. 2A). Similarly, B*08 EI8-specific cells were expanded from 0.24% ex vivo to 9.8% following culture stimulation with a B*08 EI8 peptide (Fig. 2B). Intracellular IFN-γ staining was used to assess expansions before and after cultured expansion for responses for which tetramers were not available. Using these strategies, we examined the expansion of several HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in each donor. On average, elite controllers had a significantly higher fold expansion of tetramer-specific cells than CP (P = 0.027); however, all groups had an average of a more-than-10-fold increase in virus-specific cells following expansion (Fig. 2C). Comparable results were observed when intracellular IFN-γ staining was used as a readout (data not shown). Given that a limitation of the IFN-γ ELISpot is that it does not reflect critical steps in antigen processing (31) and does not represent physiologic expression of peptide epitopes on the cell surface, we stimulated freshly isolated CD8+ T cells with autologous CD4+ T cells infected with NL4-3 virus and assessed the expansion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by tetramer staining. Similar to peptide-stimulated cultures, CD8+ T cell cocultures with NL4-3-infected autologous CD4+ T cells resulted in more-than-60-fold expansions of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Data for three elite controllers are shown (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data show that peptide stimulation or exposure to autologous CD4+ T cells infected with HIV can readily expand previously undetectable HIV-specific CD8+ T cells.

Fig 2.

Specificity of expandable CD8+ T cells responses. Flow cytometry scatterplots of HLA class I tetramer staining. Gates depict the percentages of HLA B*57 KF11-specific CD8+ T cells (A) and B*08 EI8-specific CD8+ T cells (B). Representative data for one elite controller are shown. (C) Fold increases in tetramer-specific CD8+ T cells before and after 12 days of stimulation. P values between groups were calculated using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. (D) Scatterplots showing percentages of tetramer-specific cell populations before and after cultured stimulation with NL4-3-infected autologous CD4+ T cells. Data for three elite controllers are shown.

Ex vivo-expanded HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are highly polyfunctional and capable of inhibiting in vitro virus replication.

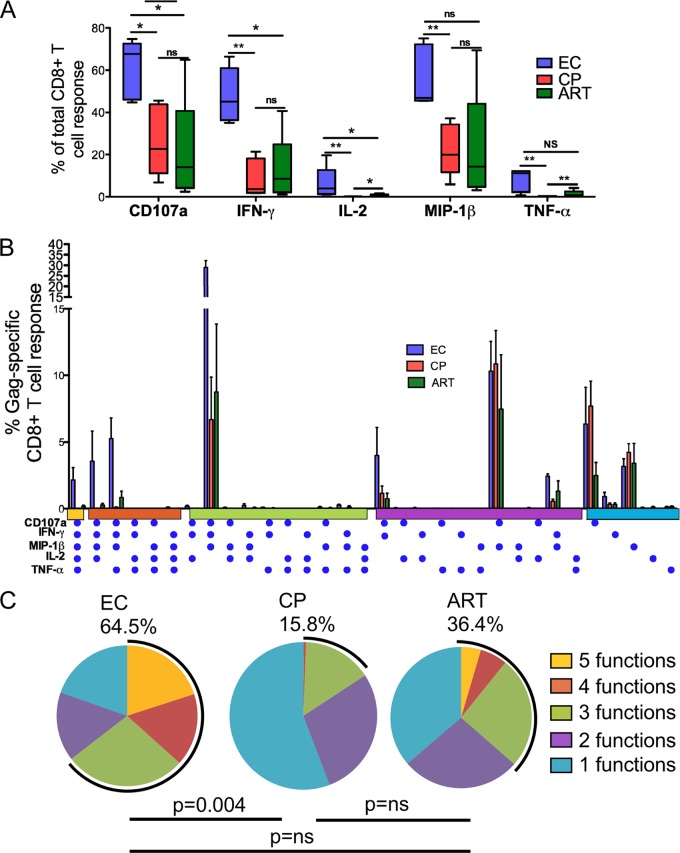

Next, we assessed multiple effector functions of ex vivo-expanded CD8+ T cells using 12-color flow cytometry after 6 h of stimulation with Gag OLPs. The assessed functions included the capacity to simultaneously produce effector cytokines and the chemokines IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and MIP-1β and the ability to release cytotoxic factors by monitoring the expression of the degranulation marker CD107a. First we examined the functional profile of each response between the groups, looking at each response as a proportion of the total CD8+ T cell response. Overall, elite controllers had significantly higher proportions of Gag-specific cells expressing CD107a and secreting IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and MIP-1β than did chronic progressors (Fig. 3A). Previous studies using ex vivo-stimulated PBMC have shown that the ability to produce 3 to 5 functions concurrently is associated with immune control (2). We therefore examined the polyfunctional profile of ex vivo-expanded Gag-specific CD8+ T cells. Boolean gating was used to generate 32 unique Gag-specific response patterns comprising every possible combination of each of the five individual measurements (Fig. 3B). Similar to what has been observed with ex vivo stimulations, elite controller cultured cells had significantly higher proportions of cells with simultaneous expression of 3 to 5 functions, whereas CP had few or no detectable cells expressing more than three functions simultaneously (64.5% and 15.8%, respectively; P = 0.004) (Fig. 3B and C).

Fig 3.

Functionality of in vitro-expanded CD8+ T cells. Gag-specific responses from 5 elite controllers (blue), 5 chronic progressors (red), and 5 ART-treated subjects (green). Five concurrent T cell functions were measured. (A) Proportions of total CD8+ T cells expressing each function. P values between groups were calculated using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.009. (B) The y axis denotes the CD8+ T cell frequency, and the x axis denotes different combinations of functions, with each function being represented by a blue dot. (C) Each pie chart represents the mean response across the five subjects to the Gag peptide stimulation. Each sector of the pie chart represents the number of functions produced, matched to the horizontal bars in panel B as indicated.

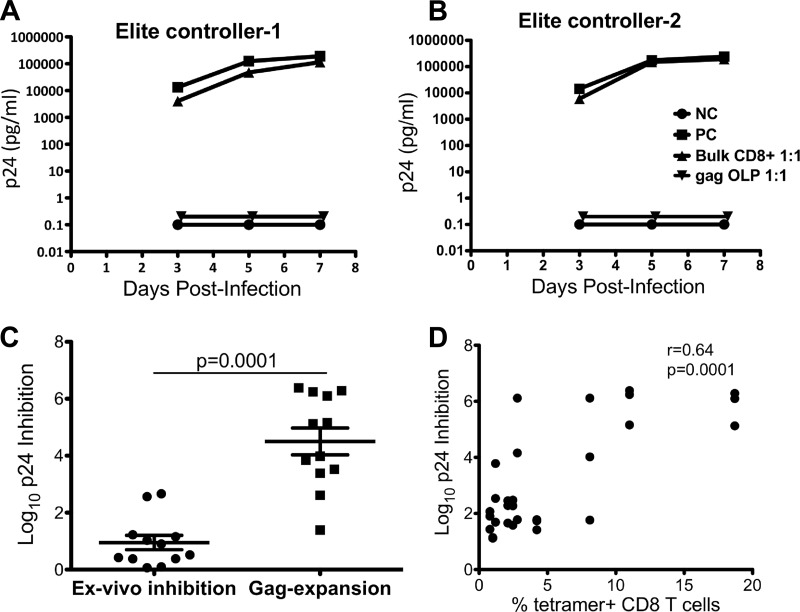

We hypothesized that the central memory cells in weak responders retain the capacity to inhibit virus replication upon stimulated expansion. To test this hypothesis, we directly compared the virus inhibitory activity of in vitro-expanded epitope-specific cells to that of unstimulated (ex vivo) CD8+ T cells. Figure 4A and B show the representative data for two elite controllers with no ex vivo CD8+ T cell viral inhibition capacity. Addition of Gag-stimulated CD8+ T cells from elite controllers to NL4-3 virus-infected autologous CD4+ T cells resulted in a 4- to 5-log reduction in p24 antigen production over a 7-day culture period. For all seven elite controllers, tested log p24 inhibitions by CD8+ T cells increased significantly after cultured stimulation with Gag OLPs compared to baseline inhibition levels (P = 0.0006) (Fig. 4C).

Fig 4.

Viral inhibition of NL4-3-infected autologous CD4+ T cells by expanded Gag-directed CD8+ T cells. NL4-3-infected CD4+ T cells were cultured at a 1:1 ratio with unstimulated or Gag-stimulated CD8+ T cells. (A) Triangles, unstimulated CD8+ T cells; inverted triangles, Gag-stimulated CD8+ T cells. Control conditions included infected CD4+ T cells alone (squares; positive control [PC]) and uninfected CD4+ T cells (circles; negative control [NC]). Day 3, 5, and 7 log10 differences in p24 values between CD4+ T cells alone and CD4+ T cells cocultured with CD8+ T cells are displayed. (B) Log10 p24 antigen concentrations in supernatants taken from infected CD4+ T cells cultured with unstimulated CD8+ T cells were compared with those in supernatants from stimulated CD8+ T cells incubated with infected CD4+ T cells. Values shown are from day 7. Lines show the mean values and the standard error of mean. (C) Each dot depicts the log10 p24 inhibition for the supernatant from each culture stimulated with a single HLA-defined optimal HIV Gag peptide plotted directly against the percentage of tetramer-positive cells cultured for 10 days.

As previously demonstrated, stimulation with optimal peptide pools resulted in heterogeneous populations of epitope-specific (tetramer-positive) cells within individual donors in spite of comparable ex vivo frequencies (Fig. 2C). We therefore examined the relationship between the frequency of epitope-specific expanded CD8+ T cells and the efficiency of HIV suppression the efficiency of HIV suppression. Cells from seven elite controllers were stimulated with optimal peptides. Three to four donor HLA-matched optimal peptides were selected based on availability of tetramers. Head-to-head comparisons of virus-suppressive activity of peptide-expanded cultures and the corresponding frequencies of expanded tetramer-specific cells showed strong positive correlations (Spearman's r = 0.64, P = 0.0001) (Fig. 4D). These data reveal a direct link between the suppressive capacity of virus-specific cells and the frequency of tetramer-positive cells, consistent with what has been observed for ex vivo responses in strong responders (32). Together, these data suggest that low-frequency Gag-directed CD8+ T cells retain the capacity to secrete multiple cytokines, carry out multiple effector functions, and maintain antiviral activity upon in vitro expansion.

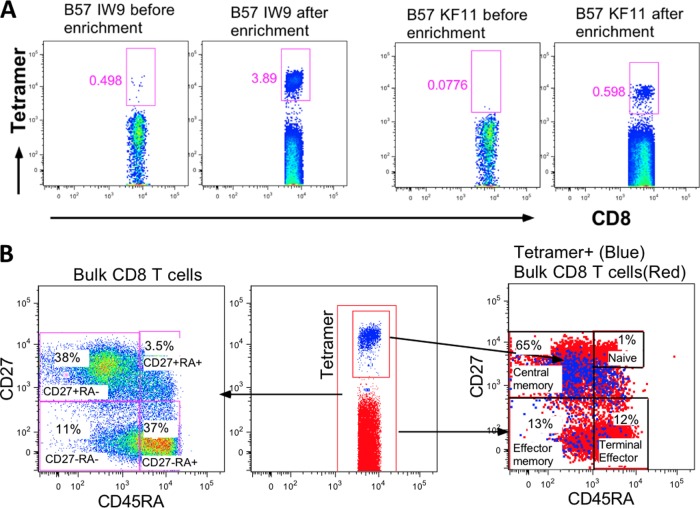

Low-frequency ex vivo Gag-specific T cells represent central memory CD8+ T cells with strong proliferative capacity.

Next we characterized the phenotype of low-frequency HIV-specific CD8+ T cells directly ex vivo. To ensure accuracy, magnetic column enrichments were performed prior to phenotyping. Freshly isolated CD8+ T cells from elite controllers were first stained with PE-conjugated tetramers followed by anti-PE-conjugated beads and passed through a magnetic column three times before washing. As shown by data from one representative elite controller (Fig. 5A), very few tetramer-positive cells were detected before enrichment, but there was a 7.8-fold increase in B*57 IW9-specific cells and a 7.7-fold increase in B*57 KF11-specific cells after magnetic-bead column enrichment. These data were reproducible in two other elite controllers (data not shown). After column enrichment, ex vivo-enriched tetramer-positive cells were stained with memory markers. We used anti-CD27 and anti-CD45RA monoclonal antibodies because these two markers have been used to define low-frequency central memory cells, which were found to be elevated after initiation of ART during acute primary HIV infection (30). Column-enriched HIV-specific CD8+ T cells showed that 65% (Fig. 5B, right panel) of the virus-specific cells had a CD27+/CD45RAlow phenotype characteristic of central memory cells (17) (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Enrichment and phenotypes of ex vivo tetramer-specific CD8+ T cells. PBMC from one representative elite controller that were stained with B*57 IW9 and B*57 KF11 tetramers. (A) Frequencies of tetramer-specific CD8+ T cells before and after column enrichment. (B) Phenotypes of column-enriched tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells. The left panel shows proportions of bulk CD8+ T cells in each gate, and the right panel shows percentages of tetramer-positive cells with the indicated phenotype.

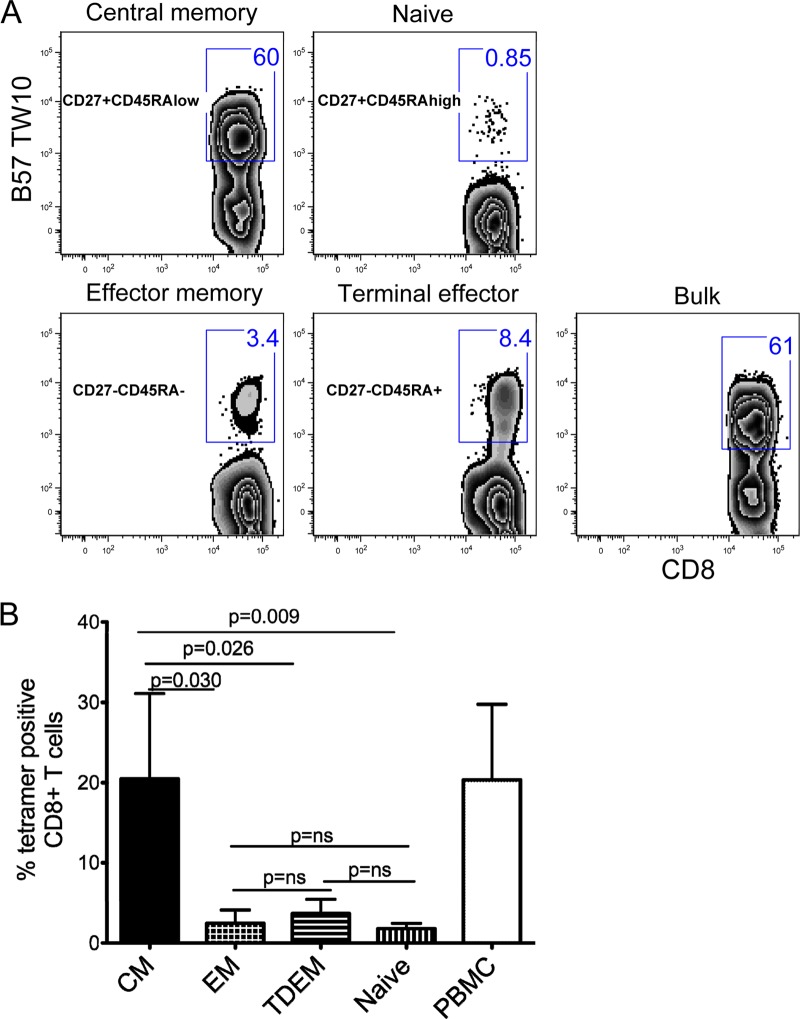

To investigate more directly whether the central memory cells are the ones that readily expanded in our in vitro culture, we freshly isolated CD8+ T cells and used FACSAria to sort four subsets based on the CD27 and CD45RA staining (Fig. 5B, left panel). The CD8+ T cell subpopulations were each cocultured with autologous CD8-depleted peptide-pulsed cells. Data for B*57 TW10-specific cells from a representative elite controller are shown (Fig. 6A). After 12 days of stimulation, tetramer-positive cells with a central memory phenotype (CD27+ CD45RAlow) increased from less than 0.5% to 60%, whereas effector subsets (CD27− CD45RA− and CD27− CD45RA+) increased only from 0.1% to 3.4% for CD27− CD45RA− cells and from 0.1% to 8.4% for CD27− CD45RA+ cells. Similar expansion profiles were observed for other tetramer specificities within this donor and two other elite controllers (Fig. 6B). Even when we took differences in baseline proportions into consideration, central memory cells had greater fold expansions compared to those of other subsets (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that among elite controllers, newly expanded Gag-specific T cell responses represent primarily proliferating central memory CD8+ T cells.

Fig 6.

PBMC from three elite controllers were sorted by flow cytometry into four different subsets based on their CD27 and CD45RA staining. Each subset was added to CD8-depleted peptide-pulsed PBMC and stimulated for 12 days as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Percentages of tetramer-positive cells for each fraction after 12 days of stimulation. (B) Summary data of the mean frequencies of the four different subsets of tetramer-specific cells after 12 days of culture. CM, central memory; EM, effector memory; TDEM, terminal effector.

DISCUSSION

Although several studies have found strong associations between the immune responses driven by CD8+ T cells and durable spontaneous control of HIV infection (4, 43), it is unclear whether these cells play an important antiviral role in a subset of elite controllers with weak or undetectable cellular responses (weak responders). In this study, we assessed the true breadth of Gag-specific responses in weak responders by measuring dominant and subdominant responses using a combination of ex vivo and cultured ELISpot assays. We further characterized the specificity and functional features of expanded CD8+ T cells using tetramer sorting and viral inhibition assays.

Our data demonstrate that stimulated cultures expanded the breadths of detectable virus-specific T cell responses mostly in elite controllers, in whom greater breadths of previously undetectable (new) responses were found. We also showed that among these low-frequency but readily expandable T cells, there are epitope-specific central memory CD8+ T cells that have a wide range of antiviral functions associated with elite controller cells, such as polyfunctionality, greater virus inhibition capacity, and high secretion of relevant soluble mediators, including MIP-1β, CD107a, and IL-2.

Previous studies have shown that CD8+ T cells restricted by the protective class I alleles HLA B*27 and B*57 have strong proliferation and expansion capacity throughout chronic HIV infection, partly due to evasion of suppressive mechanisms by T regulatory cells (14, 32). Interestingly, although protective alleles were overrepresented among the elite controllers included in our study, the greatest expansion of virus-specific T cell responses was observed in an individual that did not express any protective alleles (B*18, B*08); this individual had no measurable responses at baseline and had 16 new responses after stimulation.

Among elite controllers, marked heterogeneity of virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses has been documented (15, 38), with some individuals exhibiting a high frequency of virus-specific responses with strong viral inhibition capacity and others exhibiting very low or absent responses and limited viral inhibition capacity (42). This observation has resulted in speculation about the role that CD8+ T cell responses play in durable containment of HIV among the weak or low responders (16, 38, 42) and has led many to believe that there must be non-T-cell-mediated correlates of protection among these individuals (5, 6, 40). The mechanisms that explain the variability in breadth and function of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells among elite controllers are not fully understood, but they involve complex interactions between the level of circulating cognate antigen and the nature of the virus-specific cells responsible for sustained virus suppression. Several studies have shown that weak responders have fewer HIV antigens and no viral blips when followed longitudinally (47) despite harboring replication-competent viruses (42). In addition, weak-responder HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have lower expression of immune activation markers and have a phenotype that resembles that of a population of long-term memory cells. Together, these data support a model in which weak responders might have achieved tighter control of virus replication, lower levels of immune activation, and maintenance of a quiescent pool of central memory cells (42, 47), all features that are characteristic of a functional cure.

In this study, we examined virus inhibition activity in seven weak responders, one of which had no detectable ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot responses, and demonstrated strong virus inhibition capacities when in vitro-expanded epitope-specific CD8+ T cells were used. Interestingly, as is the case with strong responders, the levels of inhibition correlated with the frequencies of expanded HIV-specific cells, suggesting that traditional virus inhibition assays are not sensitive to measure the inhibitory capacity of low-frequency central memory cells and instead characterize mainly high-frequency cells, which are maintained by continuous antigenic stimulation and are therefore more differentiated (8). Not surprisingly, no differences in virus inhibition activity between cells from different differentiation stages have been found in studies combining phenotypic cell sorts and functional antiviral assays (17). Furthermore, until this study, no relationship between memory subsets and viral inhibition capacity of Gag-specific CD8+ T cells had been demonstrated (23).

Among elite controllers, memory cells have been identified as critical determinants of cytotoxicity (35), and in studies using peptide-based cultured IFN-γ ELISpot, expandable memory cells have been correlated with low plasma viremia in untreated individuals (7) and in individuals with other infectious diseases (26). Furthermore, strong evidence in support of their role as correlates of protection comes from nonhuman primate models (46) in which vaccine-induced memory T cells conferred protection against localized and less-diverse viruses at the site of infection (19). Although more-differentiated effector memory T cells may well be necessary to avoid rapid spread and the establishment of viral reservoirs during acute infection, generation and maintenance of a substantial central memory pool is desirable for sustained viral control, particularly in situations in which some degree of residual low-level viral replication is expected. We describe qualitative features of central memory CD8+ T cells that suggest they could play a role as correlates of protection. Moreover, although it is possible that outgrowth of autologous virus may have affected the frequency and function of expanded cells among chronic progressors, our study demonstrates clear differences between elite controllers and chronic progressors with relatively preserved absolute CD4+ T cell counts.

Although there remains the possibility that a large proportion of virus-specific cells in weak responders resides in lymphoid tissues, in this study, we have definitively proven that weak responders maintain a large pool of HIV-specific central memory T cells that are highly functional and readily expandable upon antigen stimulation. These Gag-specific CD8+ T cells are functionally similar to high-frequency virus-specific CD8+ T cells in strong responders, suggesting that a common immune mechanism of virus control in this seemingly heterogeneous population is possible. It is important to point out that our study cannot definitively rule out that alternative mechanisms, including but not limited to restriction of viral replication, are at play in the durable containment of HIV (5, 6, 10, 40). Despite this, our data suggest that interrogation of the true breadth and epitope specificity of this previously unrecognized cell pool will be critical to understanding the role that these CD8+ T cell responses played during successful containment of HIV replication and to what extent they are necessary for durable control of HIV and desirable to include in a vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (F.P. and B.D.W.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (B.D.W. and Z.M.N.).

Patient recruitment was conducted by the International HIV Controllers Study (www.hivcontrollers.org) and supported by the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Barouch DH, et al. 2002. Eventual AIDS vaccine failure in a rhesus monkey by viral escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 415:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Betts MR, et al. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781–4789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blankson JN. 2011. The study of elite controllers: a pure academic exercise or a potential pathway to an HIV-1 vaccine? Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 6:147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 68:6103–6110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brass AL, et al. 2008. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science 319:921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buzon MJ, et al. 2011. Inhibition of HIV-1 integration in ex vivo-infected CD4 T cells from elite controllers. J. Virol. 85:9646–9650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calarota SA, et al. 2008. HIV-1-specific T cell precursors with high proliferative capacity correlate with low viremia and high CD4 counts in untreated individuals. J. Immunol. 180:5907–5915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao W, et al. 2009. Premature aging of T cells is associated with faster HIV-1 disease progression. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 50:137–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carrington M, O'Brien SJ. 2003. The influence of HLA genotype on AIDS. Annu. Rev. Med. 54:535–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen H, et al. 2011. CD4+ T cells from elite controllers resist HIV-1 infection by selective upregulation of p21. J. Clin. Invest. 121:1549–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen H, et al. 2009. Differential neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication in autologous CD4 T cells by HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 83:3138–3149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day CL, et al. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deeks SG, Walker BD. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity 27:406–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elahi S, et al. 2011. Protective HIV-specific CD8+ T cells evade Treg cell suppression. Nat. Med. 17:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emu B, et al. 2005. Phenotypic, functional, and kinetic parameters associated with apparent T-cell control of human immunodeficiency virus replication in individuals with and without antiretroviral treatment. J. Virol. 79:14169–14178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Emu B, et al. 2008. HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses may contribute to the control of human immunodeficiency virus infection, but such responses are not always necessary for long-term virus control. J. Virol. 82:5398–5407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freel SA, et al. 2010. Phenotypic and functional profile of HIV-inhibitory CD8 T cells elicited by natural infection and heterologous prime/boost vaccination. J. Virol. 84:4998–5006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goulder PJ, et al. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3:212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen SG, et al. 2011. Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature 473:523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hansen SG, et al. 2009. Effector memory T cell responses are associated with protection of rhesus monkeys from mucosal simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. Nat. Med. 15:293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jager S, et al. 2011. Vif hijacks CBF-β to degrade APOBEC3G and promote HIV-1 infection. Nature 481:371–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jamieson BD, et al. 2003. Epitope escape mutation and decay of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CTL responses. J. Immunol. 171:5372–5379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Julg B, et al. 2010. Enhanced anti-HIV functional activity associated with Gag-specific CD8 T-cell responses. J. Virol. 84:5540–5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaech SM, et al. 2003. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:1191–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaufmann DE, et al. 2007. Upregulation of CTLA-4 by HIV-specific CD4+ T cells correlates with disease progression and defines a reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Immunol. 8:1246–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Keating SM, et al. 2005. Durable human memory T cells quantifiable by cultured enzyme-linked immunospot assays are induced by heterologous prime boost immunization and correlate with protection against malaria. J. Immunol. 175:5675–5680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koenig S, et al. 1995. Transfer of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to an AIDS patient leads to selection for mutant HIV variants and subsequent disease progression. Nat. Med. 1:330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koup RA, et al. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650–4655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lambotte O, et al. 2005. HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1053–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lecuroux C, et al. 2009. Identification of a particular HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell subset with a CD27+ CD45RO−/RA+ phenotype and memory characteristics after initiation of HAART during acute primary HIV infection. Blood 113:3209–3217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Le Gall S, Stamegna P, Walker BD. 2007. Portable flanking sequences modulate CTL epitope processing. J. Clin. Invest. 117:3563–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez M, et al. 2011. The expansion ability but not the quality of HIV-specific CD8(+) T cells is associated with protective human leucocyte antigen class I alleles in long-term non-progressors. Immunology 134:305–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin MP, et al. 1998. Genetic acceleration of AIDS progression by a promoter variant of CCR5. Science 282:1907–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Migueles SA, et al. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat. Immunol. 3:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Migueles SA, et al. 2008. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity 29:1009–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Migueles SA, et al. 2000. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2709–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ndhlovu ZM, et al. 2011. Mosaic HIV-1 Gag antigens can be processed and presented to human HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 186:6914–6924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pereyra F, et al. 2008. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 197:563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pereyra F, et al. 2010. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 330:1551–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saez-Cirion A, et al. 2011. Restriction of HIV-1 replication in macrophages and CD4+ T cells from HIV controllers. Blood 118:955–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saez-Cirion A, et al. 2007. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6776–6781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saez-Cirion A, et al. 2009. Heterogeneity in HIV suppression by CD8 T cells from HIV controllers: association with Gag-specific CD8 T cell responses. J. Immunol. 182:7828–7837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmitz JE, et al. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Streeck H, et al. 2008. Antigen load and viral sequence diversification determine the functional profile of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells. PLoS Med. 5:e100 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Streeck H, Frahm N, Walker BD. 2009. The role of IFN-gamma Elispot assay in HIV vaccine research. Nat. Protoc. 4:461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vaccari M, Trindade CJ, Venzon D, Zanetti M, Franchini G. 2005. Vaccine-induced CD8+ central memory T cells in protection from simian AIDS. J. Immunol. 175:3502–3507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vigneault F, et al. 2011. Transcriptional profiling of CD4 T cells identifies distinct subgroups of HIV-1 elite controllers. J. Virol. 85:3015–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Virgin HW, Walker BD. 2010. Immunology and the elusive AIDS vaccine. Nature 464:224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vollbrecht T, et al. 2010. Impact of changes in antigen level on CD38/PD-1 co-expression on HIV-specific CD8 T cells in chronic, untreated HIV-1 infection. J. Med. Virol. 82:358–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]