Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to report the findings of a study of hematopoietic cell transplant patients, describing the needs of allogeneic transplant patients at the time of discharge in regard to their functional status, quality of life (QOL), and caregiver information and comparing these needs across a number of sociodemographic, disease, and treatment characteristics. The findings of this study are part of a larger mixed-methods study, representing one data time point of the larger study.

Methods

This paper will discuss the baseline data collected at the time of discharge for 282 allogeneic transplant patients, which include sociodemographic data combined with disease, treatment, functional status, and QOL data to present a comprehensive portrait of the transplant patient at discharge.

Results

Mean age was 48 years, males represented 52%, and 22% of the patients were Hispanic. The majority of the patients had acute leukemia (55%), were diagnosed within the last 3 years, and had matched unrelated (52%) transplants. The time from transplant to discharge averaged 30 days. Mean scores for QOL (scale = 1–10, with 10 = best QOL) included a low score of 5.7 for both psychological and social well-being, 6.3 for overall QOL, and 7.1 for both physical and spiritual well-being. Males had significantly higher QOL than females, as did non-Hispanics. Patients with Hodgkin’s disease had significantly lower overall QOL scores.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual challenges which present for patients and their caregivers at the time of hospital discharge following allogeneic transplant.

Keywords: Allogeneic transplant, Discharge status, Quality of life

Introduction

Over 100 transplant centers are performing 30,000 allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplants (HCT) per year in the USA [1]. The field of transplantation has grown substantially since the first clinical trials in transplantations in the 1960s [2]. Along with the growth of knowledge regarding the biophysical experiences of the patients, studies have reported the psychosocial needs of both the patients and their families [3–7]. HCT is without a doubt one of the most physically, psychologically, and socially taxing cancer treatments for both the patients and their families. Decreases in the probability of treatment-related morbidity since 1985 have been reported and may be related to changes in both practice and patient characteristics [8]. Overall survival in the first year post transplant ranges from 22% to 90%, depending on the patient demographics, diagnosis, stage of disease, and treatment characteristics [9]. Causes of complications and death during the first year after transplant include infections, nutritional problems, failure to thrive, multiple organ failure, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and relapse [10]. Vigilant care following discharge includes careful assessment for emerging complications, prevention and early treatment of infections, and reestablishment and maintenance of a healthy nutritional status. These may be important factors in the early treatment and management of potentially lethal complications. Thus, patients’ self-care and also care provided by family caregivers may be contributing factors in survival for this population.

Few studies have focused on the time of discharge as a point of time to assess physical and psychosocial variables [4, 11]. This time has clinical relevance for the discharge teaching needed, what education the patient and caregiver need for managing physical care, and the continued psychosocial support needed up to 1 year post discharge. Information on the functional status and quality of life (QOL) of transplant patients at the time of discharge can provide valuable information for staff in identifying discharge teaching for patients and family caregivers. Identification of the effects of age, sex, and race/ethnicity on status at discharge may assist in tailoring education and delineating patients who may be especially vulnerable to post discharge complications and potential readmissions and may need additional support. The purpose of this paper is to report the findings of a study of HCT patients, describing the needs of allogeneic transplant patients at the time of discharge related to their functional status, QOL, and caregiver information and comparing these needs across a number of sociodemographic, disease, and treatment characteristics.

Methods

Design

This study describes baseline data from a study on the effects of a structured nursing intervention protocol provided by advanced practice nurses on patients being discharged from the hospital after allogeneic transplant [12]. This paper describes the health-related QOL of these allogeneic HCT patients at the time of hospital discharge and examines how QOL differs depending upon sociodemographic, disease, and treatment characteristics and physical functioning. The study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee and the Institutional Review Board.

Patients

A consecutive sample between 2005 and 2009 was drawn from one large tertiary care center in the western USA. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of a hematologic cancer, scheduled for a single allogeneic bone marrow or stem cell transplant, ready for hospital discharge, 18 years or older, residing within a 50-mile radius of the tertiary care center, had no previous hematopoietic cell transplant, and were English-speaking.

Measures

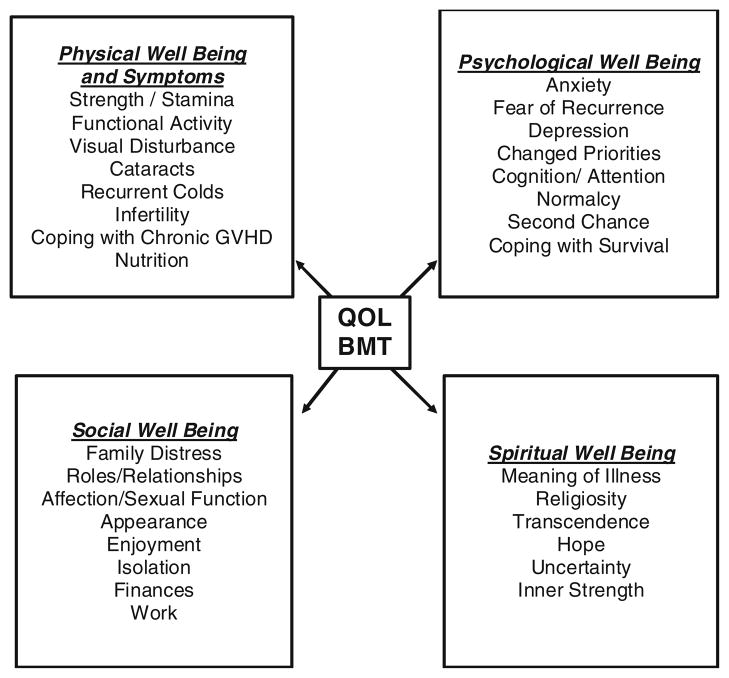

The theoretical model that guided the research was the City of Hope Quality of Life Model Applied to Bone Marrow Transplant and consisted of four dimensions: physical well-being and symptoms, psychological well-being, social well-being, and spiritual well-being (Fig. 1). Several questionnaires were used to measure the variables of interest. Socio-demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics were collected on an investigator-designed questionnaire used in previous clinical studies. Patient-related information included age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, and race. Disease-related information included diagnosis, remission status, HLA match, and time to first discharge.

Fig. 1.

City of Hope QOL/HCT model [13]

QOL was measured on the City of Hope Quality of Life in Hematopoietic Cell Transplant (COH-QOL-HCT) questionnaire. The questionnaire includes 62 QOL items divided into 4 domains or subscales (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual). All items are scored so that 10 = best QOL or the absence of symptoms or concerns. Subscale scores are produced by adding scores on each item within the subscale and then dividing by the number of items in that subscale. Adding the score of all items and dividing by the total number of items scored is used to create a total QOL score. Reported psychometric analysis revealed the content validity index of 0.90, test–retest reliability (r = 0.71, p = 0.001), total score internal consistency (r = 0.85), and subscale coefficient alphas of r = 0.40 to r = 0.86 [13]. The reliability and validity were repeated and upheld in studies at another institution [14]. The measure was used in a number of other studies at COH [15–17] and used in QOL studies in other institutions [18–21]. The instrument is available for use through the COH Pain and Palliative Resource Center (http://prc.coh.org).

An additional measure of functional status was evaluated using the Physical Functioning Subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36 Short Form (SF-36). Scores on this subscale range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing higher levels of functioning. The validity of the SF-36 was determined using data from more than 20,000 subjects. The SF-36 has a reliability of r = 0.7–0.9. Norms for the general US population and individuals with chronic conditions have been published [22]. For this study, we used only the Physical Functioning Subscale.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics. Mean scores for overall QOL, the four QOL dimensions from the COH-QOL-HCT questionnaire, and physical functioning from the SF-36 were computed. QOL and physical functioning scores were compared by selected demographic and clinical characteristics using independent t tests or a priori comparisons between groups with three or more levels. The association among continuous variables was examined using the Pearson product–moment correlation. Age, gender, length of stay (LOS), type of transplant, and diagnosis were hypothesized a priori as influencing QOL and functional status at the time of hospital discharge on the basis of clinical literature and experience. Comparisons of individual scaled items within the COH-QOL transplant measure were explored to generate hypotheses for future studies.

Results

A total of 282 patients consented to participate and were enrolled in the study. Mean age was 48 years, with a range of 19–71 years of age and a standard deviation of 13.5. Males represented 52% and 22% of the patients were Hispanic (Table 1). Eighty-five percent of the patients did not have other malignancies before transplant, and almost half of the patients had infections 1 month prior to transplant. The majority of the patients had acute leukemia (55%). Most of the patients were diagnosed within the last 3 years. The type of transplant was related in 48% and matched unrelated in 52%. Most patients had reduced-intensity transplants. Other characteristics of the transplant are also found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and characteristics, N = 282

| Characteristics | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 146 | 52 |

| Female | 136 | 48 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| Yes | 63 | 22.3 |

| No | 218 | 77.3 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 7 | 2.5 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 | 0.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 36 | 12.8 |

| Caucasian | 235 | 83.3 |

| Mixed/other | 3 | 1.1 |

| Other malignancies before transplant | ||

| None | 239 | 84.8 |

| Yes | 43 | 15.2 |

| Infection within a month prior to HCT | ||

| None | 140 | 49.6 |

| Yes | 136 | 48.2 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.7 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.4 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Acute leukemia | 163 | 54.7 |

| Chronic leukemia | 26 | 8.7 |

| Myeloproliferation disorder | 7 | 2.3 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 39 | 13.1 |

| Myelofibrosis | 10 | 3.4 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 42 | 14.1 |

| Hodgkin’s | 7 | 2.3 |

| Other | 4 | 1.3 |

| Total | 298 | 100 |

| Year diagnosed | ||

| 1988 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 1989–1994 | 7 | 2.5 |

| 1995–1999 | 12 | 4.4 |

| 2000–2004 | 43 | 15.2 |

| 2005–2008 | 219 | 77.6 |

| Types of BMT—allogeneic | ||

| Related | 135 | 47.9 |

| Matched, unrelated donor | 147 | 52.1 |

| Types of BMT—myelosuppression | ||

| Full | 126 | 44.7 |

| Partial/reduced intensity | 153 | 54.3 |

| Missing | 3 | 1.1 |

| HLA match | ||

| Match | 237 | 84 |

| Mismatched | 32 | 11.3 |

| Unknown | 9 | 3.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.4 |

| Blood/ABO | ||

| Match | 86 | 30.5 |

| Mismatch | 105 | 37.2 |

| Unknown | 85 | 30.1 |

| Missing | 6 | 2.1 |

LOS is described in several ways (Table 2). The time from admission to transplant averaged 10 days, with a range of 2–83 days. The average total hospital LOS for the transplant patients was 40 days, with a range of 18–129 days. This broad range includes those patients who were admitted and proceeded directly to transplant and those who were admitted for consolidation treatment, infection, or other reasons before moving to transplant. Finally, the time from transplant to discharge averaged 30 days, with a range of 15–78 days. This reflects an indicator of LOS that can be compared to the LOS for other cancer diagnoses and treatments.

Table 2.

LOS and QOL scores, N = 282

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS (days) | |||

| From admission to transplant | 10 | 11.4 | 2–83 |

| From admission to discharge | 40 | 16.4 | 18–129 |

| From transplant to discharge | 30 | 10 | 15–78 |

| QOL | |||

| Physical Functioning SF-36 Physical Subscalea | 33.5 | 20.4 | 0–100 |

| QOL—physical well-beingb | 7.1 | 1.2 | 3.7–9.3 |

| QOL—psychological well-beingb | 5.7 | 1.6 | 1.2–9.4 |

| QOL—social well-beingb | 5.7 | 1.6 | 2–9.7 |

| QOL—spiritual well-beingb | 7.4 | 1.6 | 2.5–10 |

| Overall QOLb | 6.3 | 1.7 | 2.8–9.1 |

Scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores equal to higher functional status

Scored from 0 to 10, with higher scores equal to higher QOL

The average SF-36 was 33.5 and ranged from 0 to 100 (Table 2). The average and range of scores for the QOL measures include the QOL-HCT domain scores and the QOL-HCToverall QOL score for the total population (Table 2). Mean scores for QOL included a low score of 5.7 for both psychological and social well-being, 6.3 for overall QOL, and 7.1 and 7.4 for physical and spiritual well-being, respectively.

Individual items from the COH-QOL-HCT were further examined in an exploratory manner (Table 3). Items that scored below 5 on the 10-point scale are presented here as areas of hypothesis generation for future studies and areas to target for clinical practice.

Table 3.

Table of mean QOL individual low items in the QOL scale

| Item | Mean score | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Physical well-being | ||

| Fatigue | 4.96 | 2.691 |

| Appetite changes | 3.90 | 2.925 |

| Physical strength | 4.94 | 2.357 |

| Sleep changes | 4.49 | 3.051 |

| Psychological well-being | ||

| Usefulness | 4.97 | 3.052 |

| In control | 4.83 | 3.086 |

| Unwanted changes in appearance | 4.08 | 3.783 |

| Fearful of recurrence | 4.61 | 5.591 |

| Social well-being | ||

| Family distress | 2.21 | 2.281 |

| Employment interference | 4.57 | 7.480 |

| Family goals interference | 4.64 | 4.777 |

| Activities at home interference | 1.59 | 5.271 |

| Spiritual well-being | ||

| Uncertainty | 4.98 | 4.922 |

Scored from 0 to 10, with higher scores equal to higher QOL

A number of demographic and clinical variables were examined to determine comparisons on QOL and functional status. In examining diagnosis, the a priori p value of ≤0.05 was present (1) for patients with Hodgkin’s disease (HD) who demonstrated decreased or significantly lower scores for overall QOL, (2) for myeloproliferative disease with significantly lower scores for psychological well-being, and (3) for myeloproliferative diseases and chronic leukemia with significantly lower scores for social well-being. Additional comparisons of QOL and functional status with gender, age, and ethnicity are found in Table 4. Females had significantly lower physical well-being than males, and unexpectedly, the youngest age group (17–35 years) had lower scores in physical well-being, social well-being, and overall QOL. For ethnicity, Hispanics had lower scores than non-Hispanics for physical well-being, social well-being, and overall QOL. Characteristics that did not show QOL and physical functional status differences across groups included marital status, race, time to first discharge (LOS), remission status, type of transplant, type of allogeneic transplant, and type of myelosuppression.

Table 4.

QOL and functional status: comparison by gender, age, and ethnicity

| Gender Male Female |

Age 17–35 36–59 60+ |

Ethnicity Hispanic Non-Hispanic |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Physical functioninga | 35.7 (21) | 34.9 (17.8) | 31.1 (21.5) |

| 31.3 (20) | 34.5 (21.6) | 34.3 (20.2) | |

| 28.8 (19.6) | |||

| Physical QOLb | 7.2 (1.1)* | 6.8 (1.1)** | 6.7 (1.2)** |

| 6.9 (1.2) | 7.1 (1.3) | 7.2 (1.1) | |

| 7.3 (0.9) | |||

| Psychological QOLb | 5.8 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.7) |

| 5.5 (1.7) | 5.5 (1.6) | 5.7 (1.5) | |

| 6.0 (1.6) | |||

| Social QOLb | 5.7 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.4)* | 5.2 (1.7)** |

| 5.6 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.5) | |

| 6.1 (1.3) | |||

| Spiritual QOLb | 7.4 (1.6) | 7.4 (1.8) | 7.6 (1.7) |

| 7.5 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.5) | 7.4 (1.7) | |

| 7.4 (1.7) | |||

| Overall QOLb | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.0)* | 6.1 (1.2)** |

| 6.2 (1.3) | 6.3 (1.2) | 6.4 (1.2) | |

| 6.6 (1.1) |

p<0.01;

p<0.05

Scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores equal to higher functionality

Scored from 0 to 10, with higher scores equal to greater functional ability

Discussion

A few studies were found that examine the demographic, physical, and psychosocial variables at the time of discharge. Two articles reported the characteristics of allogeneic transplant patients at the time of discharge, but both papers had small sample sizes [4, 11]. Studies have also been reported which assess QOL and functional status close to the time of discharge such as first clinic appointment or 90 and 100 days post transplant [23–25]. The findings reported in this paper add to the literature by presenting demographic, functional status, and QOL data for 282 allogeneic transplant patients at the time of first hospital discharge.

During the transplant hospitalization period, multiple complications can occur, including infections, gastrointestinal complications, renal and hepatic toxicities, cardiopulmonary toxicities, skin and vision changes, GVHD, and psychosocial responses including anxiety and depression [10]. The extent of these complications determines when discharge can occur. Most transplant centers identify criteria that must be met before patients may be discharged (Table 5) [26]. For allogeneic transplant patients, length of hospitalization varies depending on the primary disease, the preparatory regimen, the stem cell source, and the complications that occur following transplant. Engraftment of transplanted cells can occur 11–36 days after HCT infusion [27] and LOS may vary from 20 to 40 days [28]. The population in this study was typical, with the average LOS from transplant to discharge reported at 30 days.

Table 5.

Usual discharge criteria [26]

| Sufficient ambulation to maintain daily clinic visits |

| Adequate training of caregivers for continuing monitoring and treatment at home |

| Ability to take oral fluids |

| Tolerance of oral medications |

| IV medication deliverable in minibag preparation (e.g., cyclosporine, ganciclovir, etc.) |

| No need for i.v. narcotics |

| Manageable amounts of i.v. fluids for home delivery |

| Successful transfer from i.v. to p.o. medications 48 h prior to discharge |

| Platelets >10×109/l supportable with <2 platelet transfusions/day |

| Absence of fever and active infection |

Physical status as shown on the Physical Functioning Sub-scale of the SF-36 demonstrates that transplant patients at the time of discharge are quite debilitated. Specific items target the common functional concerns: lack of ability to do moderate activities, lift or carry groceries, climb stairs, and walk more than a mile. Specific symptom concerns are fatigue, appetite changes, physical strength changes, and sleep changes. All of these symptoms have been well-documented in the literature as common symptoms after transplant [4, 11, 23]. Fatigue during and following transplant is significantly increased and physical activity decreased [29]. Gielissen and colleagues studied fatigue in 98 patients treated with stem cell transplantation (81% allogeneic and 19% autologous) from 1 to 21 years post transplantation [30]. Findings revealed that 35% of patients reported severe fatigue, which remained more than 15 years later. Post discharge complications that also occur frequently include nutrition problems, infections, dehydration, and failure to thrive [10]. Thus, discharge teaching of patients and family caregivers needs to include specific ways to monitor and report early changes in function, nutrition and hydration status, and early signs of infection.

Transplant patients often approach transplant as a “last option for cure,” so feelings of uncertainty and fears of recurrence are understandable. Although mortality after HCT has improved within the last 20 years, it is still a substantial and reasonable fear. Relapse after transplant with progression to end-of-life care is, unfortunately, a reality for 30–50% of the patients [31]. Psychological and social well-being domains of the QOL-HCT questionnaire indicate many psychosocial concerns at the time of discharge. The results indicate difficulty feeling useful, a lack of control, changes in appearance, fears of relapse and recurrence, family distress, employment interference, and feelings of uncertainty. Items such as not feeling useful, having employment interference, and being unable to perform roles at home may be due to the patients’ functional impairment and the patients’ feelings about their incapacity to do activities performed before transplant. This lack of ability and functional impairment may make patients more prone to depression. A longitudinal study by Lee and colleagues reported that 44% of transplant patients had symptoms of depression, anxiety, or post traumatic stress disorder after transplant [24]. Grulke and colleagues who measured depression and fatigue at the time of discharge found that these symptoms increased over time [4].

A substantial and growing body of knowledge has identified the different psychosocial responses before, during, and after transplantation. Psychosocial studies that have examined patients prior to transplant have found that pretransplant overall health and mental well-being were predictors of QOL outcomes at 6 months post transplant [32, 33]. Sherman and colleagues evaluated adjustment issues and QOL in myeloma patients before transplant during their initial diagnostic evaluation [34]. Findings revealed that, before transplant, roughly 30% of patients showed clinically elevated evidence of distress, anxiety, and depression. Another study that assessed anxiety before and after transplant found elevated anxiety and/or depression in 55% of the patients with either symptom related to the QOL [24]. Results from this study add to the evidence for psychological challenges allogeneic patients experience at the time of hospital discharge post transplant.

The score on family distress was 2.21 and parallels that found on our previous studies [35]. The score illustrates patients’ concerns about their family and the burden their caregivers experience. This burden is well-documented in the literature [3, 6, 36]. The demands of care are high and potential sources of stress may include the fear of relapse, uncertainty, prolonged hospitalizations, family disruptions, infection risk, complex medication regimens, symptoms monitoring, social isolation, and patient dependency [3]. Role preparedness at the time of discharge correlates with the caregivers’ perceived rewards from caregiving such as emotional and interpersonal satisfaction [37]. Caregiver resources relate to demographic variables, financial strain, social support, personal issues, and self-care [3]. Strain on the caregiver coupled with patients feeling useless and physically debilitated may lead to increased patient distress as well as changes in the patient–caregiver dynamics. Concerns about family distress point to a clear need to prepare families for caregiving responsibilities and provide resources for use immediately following the patient’s discharge from the hospital. Concerns in this area mirror those studying other cancer populations and the burdens that occur in caregiving [36].

While not previously reported, HD patients had significantly lower psychological, social, and overall QOL when compared to populations with other diagnoses. This significant difference may be due to several reasons. Because HD has a high cure rate, patients that progress to allogeneic transplant may be those patients who are heavily pretreated for refractory disease [31]. HD patients are a younger population when compared to all HCT patients. Young adults have significant psychosocial issues when compared to the older population [38]. They are twice as likely as adults to go without insurance and to have difficulty finding work [39]. Psychologically, they have personality disruptions and high psychological distress [40]. Learning, memory, and attention problems are common [40].

To further substantiate these data about young adults, our results for those between 17 and 35 years were significantly lower for physical, social, and overall QOL. Psychological QOL for the young cancer group was much lower but not statistically significant in the young adult category. In regard to ethnic and racial differences, the Hispanic group had lower physical, social, and overall QOL. As far as we know, there are no data in the literature about this ethnic difference at the time of transplant. This group of patients in the site of the transplant center tends to be more economically disadvantaged. Therefore, this factor may affect their QOL. These findings indicate the need to tailor discharge planning education to meet the needs of specific patient populations.

Consistently, female patients in our study had significantly lower physical functioning, psychological well-being, social well-being, and spiritual well-being than the male patients. This difference was also found in the study of Prieto et al. when female sex significantly predicted poorer hospital discharge outcomes [41]. In the study of Heinonen et al. of 109 allogeneic transplant patients, females reported significantly lower well-being and fatigue from 1 to 10 years post transplant [42]. Previous studies also identify that women do experience more depression years from transplant [43].

In summary, transplant patients at the time of discharge can be significantly physically debilitated and have many QOL concerns. Women, younger patients, and Hispanic ethnicity may be risk factors for psychosocial impairment. A host of psychosocial concerns including the patients’ perception of their physical status may trigger increased psychosocial distress for both the patients and caregivers. Clearly, these findings indicate the critical need for expert, patient-specific education for allogeneic hematopoietic transplant patients and their caregivers before and at the time of hospital discharge. Applying these findings to creating and testing discharge planning approaches, to providing a variety of measures, and to evaluating their effectiveness is needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NCI R01-CA107446, Standardized Nursing Intervention Protocol for HCT Patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors do not have financial relationship with the organization that sponsored the research. We have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Contributor Information

Marcia Grant, Email: mgrant@coh.org, Division of Nursing Research and Education, City of Hope, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Liz Cooke, Division of Nursing Research and Education, City of Hope, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Anna Cathy Williams, Division of Nursing Research and Education, City of Hope, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Smita Bhatia, Division of Outcomes Research, City of Hope, Duarte, USA.

Leslie Popplewell, Division of Hematology, City of Hope, Duarte, USA.

Gwen Uman, Vital Research LLC, Los Angeles, USA.

Stephen Forman, Division of Hematology, City of Hope, Duarte, USA.

References

- 1.The Medical College of Wisconsin IatNMDP. 2011. [Accessed April 19, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelbaum FR. Hematopoietic-cell transplantation at 50. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1472–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gemmill R, Cooke L, Williams AC, Grant M. Informal caregivers of hematopoietic cell transplant patients: a review and recommendations for interventions and research. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:E13–E21. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31820a592d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grulke N, Bailer H, Kachele H, Bunjes D. Psychological distress of patients undergoing intensified conditioning with radio-immunotherapy prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2005;35(11):1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer SL, Yi JC, Storer BE, Syrjala KL. Marital adjustment, satisfaction and dissolution among hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and spouses: a prospective, five-year longitudinal investigation. Psychooncology. 2010;19(2):190–200. doi: 10.1002/pon.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson ME, Eilers J, Heermann JA, Million R. The experience of spouses as informal caregivers for recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(3):E15–E23. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819962e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrykowski M, McQuellon R. Psychosocial issues in hematopoietic cell transplantation. In: Blume KBSJF, Appelbaum FR, editors. Thomas’ hematopoietic cell transplantation. 3. Blackwell Science LTD; Malden, Massachusetts: 2004. pp. 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horan JT, Logan BR, Agovi-Johnson MA, Lazarus HM, Bacigalupo AA, Ballen KK, Bredeson CN, Carabasi MH, Gupta V, Hale GA, Khoury HJ, Juckett MB, Litzow MR, Martino R, McCarthy PL, Smith FO, Rizzo JD, Pasquini MC. Reducing the risk for transplantation-related mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: how much progress has been made? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):805–813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquini MC, Wang Z. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Part II- CIBMTR Summary Slides. CIBMTR Newsl. 2009;15(2):7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant M, Cooke L, Bhatia S, Forman S. Discharge and unscheduled readmissions of adult patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: implications for developing nursing interventions. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(1):E1–E8. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E1-E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacker ED, Ferrans CE. Quality of life immediately after peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(4):312–322. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200308000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant M Primary investigator. RO1 CA 107446: a standardized nursing intervention protocol for HCT patients. National Cancer Institute, City of Hope Medical Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant M, Ferrell B, Schmidt GM, Fonbuena P, Niland JC, Forman SJ. Measurement of quality of life in bone marrow transplantation survivors. Qual Life Res. 1992;1(6):375–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00704432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleh US, Brockopp DY. Quality of life one year following bone marrow transplantation: psychometric evaluation of the quality of life in bone marrow transplant survivors tool. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(9):1457–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong FL, Francisco L, Togawa K, Bosworth A, Gonzales M, Hanby C, Sabado M, Grant M, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Long-term recovery after hematopoietic cell transplantation: predictors of quality-of-life concerns. Blood. 2010;115(12):2508–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant M. Assessment of quality of life following hematopoietic cell transplantation. In: Forman SJ, Blum KG, Thomas ED, editors. Hematopoietic cell transplantation. 2. Blackwell Science, Inc; 1999. pp. 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- 17.King CR, Ferrell BR, Grant M, Sakurai C. Nurses’ perceptions of the meaning of quality of life for bone marrow transplant survivors. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18(2):118–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch JC, Morris ME, Bociek G, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, Armitage JO. Quality of life of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. Poster session presented at the annual conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research; Prague, Czech Republic. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byar KL, Eilers JE, Nuss SL. Quality of life 5 or more years post-autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(2):148–157. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whedon M, Stearns D, Mills LE. Quality of life of long-term cancer survivors. Oncol (Williston Park) 1997;11(4):565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris AS, Lynch JC, Bociek G, Tarantolo S, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, Armitage JO. Preliminary quality of life findings of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant untilizing the City of Hope National Medical Center and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Instruments. Clin Ther Supl D. 2003:D21–D22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(11):1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Antin JH, Kirkpatrick T, Prokop L, Alyea EP, Cutler C, Ho VT, Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Fisher DC, Logan B, Soiffer RJ. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2005;35(1):77–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, Storer B, Sanders JE, Flowers ME, Martin PJ. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291(19):2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flowers ME, Sullivan KM. Management of patients undergoing marrow or blood stem cell transplantation. In: Atkinson KRC, Ritz J, Fibbe W, Ljungman P, Brenner M, editors. Clinical bone marrow and blood stem cell transplantation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. pp. 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz N. Peripheral Blood Hematopoietic Cells for Allogeneic Transplantation. In: Blume KG, Fredrick SJF, Appelbaum R, editors. Thomas’ hematopoietic cell transplantation. 3. Blackwell Science Ltd; Malden, Massachusettes: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavletic ZS, Bishop MR, Tarantolo SR, Martin-Algarra S, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, Reed EC, Gross TG, Kollath J, Nasrati K, Jackson JD, Armitage JO, Kessinger A. Hematopoietic recovery after allogeneic blood stem-cell transplantation compared with bone marrow transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1608–1616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danaher EH, Ferrans C, Verlen E, Ravandi F, van Besien K, Gelms J, Dieterle N. Fatigue and physical activity in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(3):614–624. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.614-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gielissen MF, Schattenberg AV, Verhagen CA, Rinkes MJ, Bremmers ME, Bleijenberg G. Experience of severe fatigue in long-term survivors of stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2007;39(10):595–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peniket AJ, Ruiz de Elvira MC, Taghipour G, Cordonnier C, Gluckman E, de Witte T, Santini G, Blaise D, Greinix H, Ferrant A, Cornelissen J, Schmitz N, Goldstone AH. An EBMT registry matched study of allogeneic stem cell transplants for lymphoma: allogeneic transplantation is associated with a lower relapse rate but a higher procedure-related mortality rate than autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2003;31(8):667–678. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andorsky DJ, Loberiza FR, Lee SJ. Pre-transplantation physical and mental functioning is strongly associated with self-reported recovery from stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2006;37(9):889–895. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Brink MR, Porter DL, Giralt S, Lu SX, Jenq RR, Hanash A, Bishop MR. Relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2010;16(1 Suppl):S138–S145. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, Spohn R, Tricot G. Psychosocial adjustment and quality of life among multiple myeloma patients undergoing evaluation for autologous stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2004;33(9):955–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris ME, Grant M, Lynch JC. Patient-reported family distress among long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldredge DH, Nail LM, Maziarz RT, Hansen LK, Ewing D, Archbold PG. Explaining family caregiver role strain following autologous blood and marrow transplantation. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(3):53–74. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooke L, Chung C, Grant M. Psychosocial care for adolescent and young adult hematopoietic cell transplant patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29(4):394–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen J. A third of young adults uninsured in 2008: US report. Washington: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson K, Palmer S, Dyson G. Adolescents & young adults: issues in transition from active therapy into follow-up care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, Carreras E, Rovira M, Cirera E, Gasto C. Psychometric study of quality of life instruments used during hospitalization for stem cell transplantation. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinonen H, Volin L, Uutela A, Zevon M, Barrick C, Ruutu T. Gender-associated differences in the quality of life after allogeneic BMT. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2001;28(5):503–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooke L, Gemmill R, Kravits K, Grant M. Psychological issues of stem cell transplant. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]