Abstract

We describe a systematic approach to modeling blood flow using reconstructed capillary networks and in vivo hemodynamic measurements. Our objective was to produce flow solutions that represent convective O2 delivery in vivo. Two capillary networks, I & II, (84×168×342 & 70×157×268 μm3) were mapped using custom software. Total network red blood cell supply rate (SR) was calculated from in vivo data and used as a target metric for the flow model. To obtain inlet hematocrits, mass balances were applied recursively from downstream vessels. Pressure differences across the networks were adjusted to achieve target SR. Baseline flow solutions were used as inputs to existing O2 transport models. To test the impact of flow redistribution, asymmetric flow solutions (Asym) were generated by applying a ±20% pressure change to network outlets. Asym solutions produced a mean absolute difference in SR per capillary of 27.6 ± 33.3% in network I & 33.2 ± 40.1% in network II vs. baseline. The O2 transport model calculated mean tissue PO2 of 28.2 ± 4.8 & 28.1 ± 3.5 mmHg for baseline and 27.6 ± 5.2 & 27.7 ± 3.7 mmHg for Asym. This illustrates that moderate changes in flow distribution within a capillary network have little impact on tissue PO2 provided that total SR remains unchanged.

Keywords: blood flow, capillary networks, oxygen transport modeling, red blood cell supply rate

INTRODUCTION

In our previous paper we described an experimental protocol and software package for reconstructing 3D capillary networks from video recordings of microvascular blood flow in vivo (3). We also described how measurements of red blood cell (RBC) velocity, hematocrit, RBC supply rate (SR), and RBC O2 saturation in these capillaries were acquired from the same videos used to reconstruct the network. By indexing quantitative measurements of hemodynamics (RBC velocity, hematocrit, RBC supply rate) and O2 saturation onto specific vessels within a 3D map of a vascular network, we produce a complete and rich data set on which to base related computational models. However, there are two primary limitations that prevent us from directly using the experimental data in existing O2 transport models (14). First, it is not always possible to acquire a complete hemodynamic dataset for each vessel within a full capillary network due to the topology of the network and hardware limitations under low light levels conditions (14). In capillary networks it is not unusual for one vessel to mask another vessel (independent data cannot be acquired from each vessel) or for there to be very short connecting vessels (there is not enough spatial data for velocity measurements) (14). The wavelengths used for spectrophotometric analysis of O2 saturation result in very low light level conditions in thicker tissues such as the rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle. Some vessels may be too dark to obtain data from, or may require long exposure times and slower framing rates resulting in blurred images of high velocity RBCs. Second, to record a complete vascular map, multiple overlapping fields of view must be acquired sequentially in time to accurately reconstruct the network, and to obtain in-focus video data in as many capillaries as possible. Thus, hemodynamic and O2 saturation data cannot be acquired simultaneously in all vessels (except for 2D networks entirely visible in one field of view). The inability to simultaneously measure conditions in every vessel, combined with the temporal variability in RBC flow in and among capillaries creates a situation where the collected experimental data may not represent an accurate flow balance throughout a branching network despite best efforts to obtain representative data for each vessel.

Our approach to overcome the above challenges was to apply a steady state flow model that appropriately represents the convective supply of oxygen as observed in vivo across the entire network. The flow model includes rheological dependence of RBC distribution at bifurcations as well as the dependence of viscosity in small vessels on local hematocrit and velocity (4). Since both RBC velocity and capillary hematocrit are highly variable among vessels, we chose to focus on RBC supply rate as the metric to match with our flow model. Our rationale for using RBC supply rate was that supply rate is effectively a direct measure of how much O2 can be transported in a capillary network. Although velocity measurements have been used by others as the target metric (11, 12), velocity alone cannot be used to calculate O2 transport in vessels without corresponding hematocrit data to calculate supply rate. The same is true of using hematocrit as the metric without data on velocity. We also propose that attempting to precisely match supply rate on a vessel-by-vessel basis is unnecessary since diffusional exchange among capillaries will compensate for a mismatch in individual vessel supply rate provided that the total network supply rate is maintained. For this reason we adjusted the driving pressure across the network until the total RBC supply rate computed using the flow model matched the total red blood cell supply rate measured in the network in vivo. In vessels for which we did not have supply rate data, we applied a mass balance with measurements recorded from connected downstream or upstream vessels (14).

The first stage in applying the steady state flow model was to establish this basic mass balance, using hemodynamic measurements in daughter vessels, and test the validity of the resulting calculated blood flow in upstream parent vessels. Second, it was necessary to verify that the rule for distribution of RBC supply rate at bifurcations could be applied to capillary bifurcations in skeletal muscle. Published bifurcation rules acquired for larger vessel bifurcations in different tissues are described by continuous functions that calculate non-discrete cell distributions that cannot directly be rationalized with individual cell transits (8, 9, 11). Select experimental data sets, where data from parent and both daughter vessels could be acquired simultaneously, were used to compare flow distributions measured experimentally with the distributions predicted by empirical rules. The third stage was to determine how much effect an error in estimating the total RBC supply rate in the network would have on the computed tissue PO2 distribution by varying network supply rate by up to ±40%. Finally, since we matched the total RBC SR to the network but not the RBC SR in each individual vessel, we needed to determine how variability in RBC supply rate among capillaries affects the tissue PO2 distribution. These last two stages were studied using two reconstructed capillary networks and their associated hemodynamic and O2 saturation data. Results from the O2 transport model demonstrate that matching RBC supply rate to individual vessels is not necessary, provided that the total RBC supply rate to the network is maintained. Changes to the total network supply rate of ±20% result in errors in tissue PO2 proportional to approximately 1/2 the change in supply rate. From this we conclude that the approach we outline in this paper is a robust way to apply measured hemodynamic data to reconstructed capillary networks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Intravital Video Microscopy

Intravital video sequences of capillary networks in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) from previous work were used in this study (3). The experimental protocol used to visualize blood flow in the microvasculature has been described previously (3). Animal protocols were approved by the University of Western Ontario’s Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly selected on the day of experiment and weighed to verify a suitable mass between 140 – 180g. Animals were anaesthetized with a sodium pentobarbital solution (6.5 mg/100g body weight) and mechanically ventilated at a mean rate of 74 breaths per minute. A cannula was inserted into the carotid artery to monitor heart rate and blood pressure using an attached pressure transducer. Supplementary saline and anesthetic were delivered as needed via a catheter inserted into the jugular vein. EDL muscle was dissected as described by Tyml and Budreau (13). The isolated muscle was secured with silk ligature and reflected on the microscope stage such that the lateral side of the muscle faced the objectives. The muscle was secured at approximately its in situ resting length and orientation, isolated from the air with polyvinylidene chloride film (Saran Wrap, Dow Chemical) and a glass cover slip, and kept moist with warm saline. At the completion of experimental protocols animals were euthanized using an intravenous injection of Euthanyl Forte (Bimeda MTC).

The video acquisition system utilized a Nikon Diaphot 300 inverted microscope fitted with a 100W white light Xenon lamp for transillumination of the EDL muscle. The intravital image was reproduced via a parfocal beam splitter fitted with 420 nm & 431 nm band pass filters. Simultaneous frame-by-frame video was captured at each wavelength using two identical computer systems, each connected to a charged-coupled device camera through real-time analog to digital capture cards. A live video output was displayed locally on closed circuit monitors to allow the user to select regions of interest and maintain focus during capture.

Mapping Bifurcation and Network Morphology

Vascular morphology for complete networks was determined using custom MATLAB software that has been previously described (3). Briefly, multiple intravital video sequences were recorded in overlapping fields at multiple focal depths in order to capture the complete geometry and connectivity of the network within a region of interest. Variance images were generated offline from each video sequence using the method described by Japee et al. (5). Variance images were used for registration of overlapping fields and fields at different focal planes. Individual vessel segments were selected from functional images and joined using automated and manual methods described elsewhere (3). The resulting reconstructed networks accurately map the functional morphology of contiguous networks observed in vivo.

Isolated divergent bifurcations used to analyze mass balance and cell distribution were captured and mapped (Figure 1) using a similar process as that described above. Individual bifurcations were selected on the basis that all three branches lay in approximately the same focal plane.

Figure 1.

Example of a diverging isolated bifurcation mapped using custom 3D microvascular mapping software. Direction of flow is from parent to daughters.

Capillary Hemodynamic Measurements

Hemodynamic measurements were made offline from video sequences of individual, in-focus capillaries within each field of view. Automated measurements for velocity, lineal density and supply rate were made on a frame-by-frame basis from each 60s sequence using custom analysis software described elsewhere (3, 6). Briefly, capillaries within each field were selected and outlined from variance images generated by processing the intravital video sequences. Variance images provide high contrast delineation between tissue and the luminal space swept out by the passage of RBCs. Space-time images were created for each vessel thereby describing the light intensity along the centerline of a vessel over time. In the resulting space-time images, due to the wavelengths selected (420 & 431 nm), areas containing RBCs have high contrast relative to the surrounding plasma (2, 6). Automated routines were used to segment the RBCs from plasma in order to measure RBC lineal density and to quantify the displacement of the RBC column from frame-to-frame to measure the RBC velocity. Tube hematocrit (HctT) for each video frame was calculated as the product of lineal density and RBC volume divided by the volume of the vessel segment. Vessel segment volume was calculated using mean vessel diameter and assumed a circular cross section. Frame-by-frame RBC supply rate (RBC/sec) was calculated as the product of the RBC velocity (mm/sec) and RBC lineal density (RBC/mm). Hemodynamic values averaged over the collection period were indexed to corresponding vessels in reconstructed networks and isolated bifurcations. RBC oxygen saturations were determined using custom software that employs a spectrophotometric technique (calibrated in vivo) which calculates RBC oxygen saturation using RBC optical density as recorded at each wavelength similar to what has been described previously (3, 6).

Mass Balance at Bifurcations

In order to assess the validity of applying a mass balance to supplement direct measurements in a complete network, 8 diverging bifurcations were examined. As previously mentioned, bifurcations were selected on the basis that the parent and both daughter vessels lay within approximately the same plane of focus thus allowing for simultaneous measurement of velocity, hematocrit and RBC supply rate.

The software used to calculate capillary segment hemodynamics determines a mean velocity along the segment of interest. Since the empirical formula used for relative viscosity is based on Poiseuille’s law (10), the effective cylindrical diameter (Dcyl)for each capillary segment was determined by:

| (1) |

where n represents the number of measured diameters (Di) along the vessel length. Average RBC supply rate was calculated from measured lineal density and velocity in parent and daughter vessels over a 60s sequence, as well as in 1s averages (30 frames) throughout the entire sequence. The resulting values for average parent RBC supply rate over the entire sequence duration and on a second-by-second basis were then compared with the sums of RBC supply rate in the corresponding daughter vessels over each time period:

| (2) |

Where SRp is the calculated RBC supply rate in the parent vessel as determined by the sum of the measured RBC supply rate in the two daughters (SRd1 & SRd2) over the measurement period. SRp was compared against the observed supply rate in the parent vessel using a linear regression (Prism 4.0a, GraphPad Software).

Cell Distribution at Bifurcations

The fractional distribution of cells in daughter vessels is primarily determined by the relative downstream flow in each branch. When considering convective transport of oxygen via RBCs in a computational model it is important that an accurate application of this rheological distribution be observed in order for the construct to remain consistent with the observed biophysical properties. This distribution has been previously described in vessels between 7 – 50 μm (7). In capillary bifurcations, RBCs usually arrive at a branch individually or in short trains of a few cells and must traffic down one of the two possible paths. The empirically derived bifurcation rule is continuous in nature and cannot directly account for the discrete distribution of RBCs on a cell-by-cell basis. Due to the necessity of applying such a rule in a mathematical model of blood flow, it was important to determine the relevance of a continuous function compared to discrete experimental observations in vivo. Using the calculated parent RBC supply rate (SRp) defined in equation 2 and the fractional blood flow in each daughter branch described by:

| (3) |

where blood velocity (vb) is defined as vb = (HctT/HctD) •vc, given measured cell velocity (vc), tube hematocrit (HctT) calculated from measured values, and discharge hematocrit (HctD) obtained via Equation 5 below.

The fractional distribution of cells can then be calculated using the aforementioned empirical rule (7, 8):

| (4) |

where the asymmetry of the distribution is represented by A = −0.004 – 6.99• log((Dcyld1/Dcyld2)/Dcylp) and B B = 1.01 + 6.716• ((1 − HctDp)/Dcylp) which characterizes the sigmodal shape of the distribution, and Xo = 0.047 - 0.00123 •Dcylp, which is the fractional blood flow threshold below which no cells enter the downstream branch. This distribution relies on the conversion of the tube hematocrit (HctT) into a discharge hematocrit (HctD) using the relationship described by Pries et al. (9)

| (5) |

as it relates to the apparent viscosity of blood in narrow tubes.

Red blood cell supply rates predicted by the bifurcation rule were compared with measured values in each daughter vessel using linear regression (Prism 4.0a, GraphPad Software).

Modeling Flow in 3D Capillary Networks

Several approaches were employed to produce an accurate representation of the flow conditions observed in vivo. Missing velocity and hematocrit values in parent vessels were determined by using software that applied a mass balance at bifurcations similar to that described by Wetter et al. (14). Parent vessel blood flow (Qbp) was taken as the sum of blood flow (Qbd1 & Qbd2) from each daughter vessel as calculated by equation 3

| (6) |

Values for discharge hematocrit (HctDp) were calculated by dividing the volume of cell flow in the two daughters (Qbd1 & Qbd2) by parent vessel blood flow from equation 6

| (7) |

where the volume of cell flow in each daughter is .

Similarly, blood velocity in parent vessels (Vbp) was determined by

| (8) |

In cases where data in a daughter vessel was not available, the measured values from the corresponding paired branch were assigned. Where necessary these approaches were applied sequentially upstream to provide a calculated hematocrit and velocity in each inlet vessel.

Observed network red blood cell supply rate (SRN) for the volume was calculated from vessels that lay in the network cross-section containing the largest proportion of vessels with direct hemodynamic measurements. Vessels included in the cross section that were not measured experimentally were assigned a mean supply rate calculated manually from the values measured in other vessels within the cross section.

The calculated inlet hematocrits were incorporated into the reconstructed networks and an established flow model created by Goldman and Popel (4), based on equations derived by Pries et al. (11, 12), was applied. Pressure boundary conditions were adjusted iteratively at the network inlets and outlets to approximately match the relative velocity differences in individual vessels observed experimentally. Finally, the boundary conditions were linearly scaled to match the cross-sectional SRN.

Two sets of flow solutions were created. One set closely matched the conditions observed in vivo; approximately matching observed velocity and hematocrit in each vessel, and matching measured total cross sectional SRN to within < 0.1%. A second set of flow solutions was created that applied an asymmetric increase/decrease in pressure gradient onto the network outlets while maintaining total SRN in order to test the relative sensitivity of using cross sectional supply rate as a target for observationally matched solutions.

To test the effect of changes in SRN on tissue PO2 an additional series of flow solutions were created that applied changes to SRN in 10% increments spanning from −40% to +40% of the total cross sectional supply rate matched flow solutions.

Oxygen Transport Model

The O2 transport model is based on the model described previously by Goldman and Popel (4). Our reconstructed capillary networks have replaced the idealized parallel vessel arrangement, and the flow solutions from the 3D networks have been used as input into the model rather than statistical velocity and hematocrit profile.

The tissue oxygen partial pressure, P(x,y,z,t), is described by:

| (9) |

where D, α, and M(P) are the diffusion coefficient, solubility and consumption rate of O2 respectively of the tissue. The influence of myoglobin on O2 transport in the tissue is also included where cMb, DMb, and SMb(P) = P/(P + P50,Mb) are the myoglobin concentration, diffusion coefficient and oxygen saturation. The following equation describes the convective O2 transport in the blood at each constituent axial location (ξ) using the mass balance equation for blood hemoglobin oxygen saturation S(ξ,t):

| (10) |

where u is the mean blood velocity, R is capillary radius, j is the oxygen flux out of the capillary at the axial location (ξ,θ), C is the O2-binding capacity of blood, Pb is the intracapillary PO2 and αb is the solubility of O2 in plasma.

The exchange of O2 between capillaries and tissue is given by following flux equation:

| (11) |

where κ is the mass transfer coefficient and Pw is the tissue PO2 at the capillary surface. κ reflects the impact of red blood cell spacing on diffusional exchange between capillary and tissue, and hence is a function of the capillary hematocrit at that location. The boundary condition at the capillary-tissue interface was specified as:

| (12) |

where n is the unit vector normal to the capillary surface and j is defined by Eq. 11. In the current work, the boundary condition at the tissue boundaries was specified as a zero flux boundary condition.

As outlined in Goldman et al. (4) the above O2 transport equations 9 – 12 were combined with Michaelis-Menten consumption kinetics, M = M0 P/(P + Pcr) and the Hill equation for oxyhemoglobin saturation, S(P) = Pn/(Pn + P50n) to define O2 transport within the 3D volume.

All simulations employed a grid spacing of 2 μm to provide adequate spatial resolution for calculations of tissue PO2 within tissue elements. A summary of network geometry and simulation parameters can be found in Table 1. The initial condition for all of the simulations was zero tissue PO2. The simulations were run on an Apple Mac Pro workstation with the approximate runtime to a steady state solution of 18 hours per run depending on the size of the reconstructed network.

Table 1.

Summary of network geometry and hemodynamic parameters used in oxygen transport simulations.

| Network | Volume Dimensions (μm × μm × μm) | Volumetric Capillary Density (%) | Calculated RBC SR/Volume (mL RBC x mL tissue−1 x s−1) | Entrance Saturation (%) | Consumption Rate (mL O2 x mL tissue−1 x s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 84 × 168 × 342 | 1.9 | 8.3 E-4 | 63 | 1.5 E-4 | |

| II | 70 × 157 × 268 | 2.4 | 8.5 E-4 | 63 | 1.5 E-4 | |

RESULTS

Isolated Bifurcations – Upstream Mass Balance

An example of second by second measurements at an isolated bifurcation is shown in Figure 2. This example is representative of how the sum of daughter supply rates matches the measured supply rate in the parent vessel over time. Figure 3 shows the regression analysis for mean measured red blood cell supply rate in the parent vessel (SRp) versus the mean sum of the corresponding daughter vessels supply rates (SRd1 + SRd2), applying a mass balance on RBCs at the bifurcation. Regression analysis verified that measurements of SRp were not significantly different from the sum of supply rates in the daughters (linear regression: y = 1.184 + 0.91x, r2 = 0.9731; p < 0.0001) across the bifurcations sampled. The 95% confidence interval for the slope includes 1.0 (0.76 to 1.06) and for the intercept it includes zero (−0.25 to 2.6 RBC/s).

Figure 2.

Measured red blood cell supply rate in each branch of bifurcation H recorded over a 60s period. A mass balance was performed on a second-by-second basis to produce the SRd2 + SRd3 curve which shows the sum of the SR in the two daughter vessels over the collection period.

Figure 3.

Linear regression of the mean measured supply rate for parent vessels in each isolated bifurcation vs the sum of the mean measured supply rate in the corresponding daughter vessels. N = 8 bifurcations.

Summary data for each sampled bifurcation can be found in Table 2 which indicates effective diameter, hematocrit, velocity, and measured supply rates for each branch of the bifurcation as well as parent supply rate estimated from the mass balance at the bifurcation and the daughter supply rates predicted by the bifurcation rule. Effective vessel diameters of parent vessels ranged from 4.8 – 6.0 μm with mean tube hematocrits from 7.2 ± 3.8 to 20.4 ± 3.8 % and cell velocities ranging from 102.0 ± 48.8 to 351.1 ± 67.0 μm/s.

Table 2.

Summary of isolated bifurcation data. The table indicates mean values for Effective Diameter (ED), Discharge Hematocrit (Hct), Blood Velocity (Vel), Supply Rate (SR), Predicted Supply Rate by Mass Balance (PSRMB) and Predicted SR by the Bifurcation Rule.

| Bifurcation ID | EDp,d1,d2 (μm) | Hctp,d1,d2 (%) | Velp,d1,d1 (μm/s) | SRp,d1,d2 (cells/s) | PSRMBp (cells/s) | PSRBRd1,d2 (cells/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| A | 4.94 | 17.20 ± 5.36 | 177.99 ± 80.45 | 8.67 ± 4.64 | 9.46 ± 3.17 | - |

| 4.86 | 12.89 ± 3.67 | 74.64 ± 37.71 | 3.02 ± 1.80 | - | 2.69 ± 2.41 | |

| 4.79 | 19.18 ± 4.48 | 118.03 ± 43.64 | 6.44 ± 2.61 | - | 6.14 ± 2.98 | |

|

| ||||||

| B | 5.90 | 14.59 ± 2.81 | 101.95 ± 48.79 | 6.86 ± 3.63 | 7.99 ± 4.14 | - |

| 5.14 | 17.56 ± 3.14 | 52.33 ± 37.71 | 3.24 ± 2.54 | - | 2.86 ± 2.40 | |

| 5.66 | 16.21 ± 3.20 | 70.68 ± 26.19 | 4.78 ± 2.1 | - | 4.49 ± 2.11 | |

|

| ||||||

| C | 6.00 | 12.76 ± 4.46 | 156.07 ± 79.59 | 9.09 ± 4.68 | 9.23 ± 3.23 | - |

| 5.93 | 11.59 ± 3.81 | 126.75 ± 35.85 | 6.61 ± 2.88 | - | 7.98 ± 3.36 | |

| 6.06 | 13.61 ± 3.65 | 30.02 ± 22.95 | 2.59 ± 1.70 | - | 1.19 ± 1.12 | |

|

| ||||||

| D | 5.93 | 7.47 ± 3.77 | 332.21 ± 72.26 | 10.92 ± 5.32 | 11.45 ± 3.60 | - |

| 5.39 | 6.19 ± 3.16 | 229.04 ± 61.06 | 5.02 ± 2.53 | - | 7.45 ± 3.87 | |

| 5.65 | 9.4 ± 3.13 | 173.52 ± 31.47 | 6.45 ± 2.20 | - | 5.22 ± 2.69 | |

|

| ||||||

| E | 5.50 | 10.02 ± 6.2 | 351.08 ± 67.02 | 13.50 ± 8.53 | 13.06 ± 4.90 | - |

| 5.86 | 7.26 ± 3.51 | 176.34 ± 29.27 | 5.51 ± 2.77 | - | 7.90 ± 4.08 | |

| 5.52 | 8.84 ± 3.44 | 226.16 ± 42.11 | 7.58 ± 2.95 | - | 10.97 ± 5.30 | |

|

| ||||||

| F | 4.79 | 7.16 ± 3.80 | 196.59 ± 73.87 | 4.04 ± 2.62 | 4.31 ± 2.25 | - |

| 5.04 | 5.55 ± 2.85 | 60.19 ± 32.00 | 0.99 ± 0.66 | - | 0.95 ± 1.14 | |

| 5.74 | 10.30 ± 3.95 | 79.27 ± 36.34 | 3.36 ± 2.05 | - | 2.15 ± 1.72 | |

|

| ||||||

| G | 5.78 | 20.43 ± 3.81 | 119.86 ± 31.15 | 10.16 ± 3.27 | 10.08 ± 3.42 | - |

| 5.49 | 15.77 ± 2.76 | 95.57 ± 34.89 | 5.79 ± 2.46 | - | 8.75 ± 2.70 | |

| 5.30 | 19.68 ± 3.70 | 60.01 ± 16.65 | 4.34 ± 1.54 | - | 3.89 ± 1.68 | |

|

| ||||||

| H | 5.33 | 13.4 ± 3.58 | 206.78 ± 48.68 | 9.93 ± 3.10 | 10.43 ± 2.52 | - |

| 5.72 | 16.20 ± 3.05 | 121.95 ± 28.58 | 8.10 ± 2.10 | - | 7.30 ± 2.45 | |

| 4.83 | 8.78 ± 3.19 | 92.45 ± 31.01 | 2.36 ± 1.06 | - | 3.10 ± 1.92 | |

Isolated Bifurcations – Downstream RBC Distribution

Supply rate data, represented in Figure 2, is plotted in Figure 4 in terms of the distribution of RBCs at the bifurcation as a function of the flow fraction compared against the predictions of the bifurcation rule for that bifurcation. Regression analysis was used to compare, for eight bifurcations, the measured RBC supply rate in daughter branches versus the distribution that was predicted by the bifurcation rule (Figure 5) given the hemodynamic conditions measured in each parent vessel and the diameter of their daughter vessels. Mean supply rates in the daughter branches were not found to be statistically different than supply rates predicted by the bifurcation rule (linear regression: y = −0.86 + 1.27x, r2 = 0.7517; p = 0.0001). The 95% confidence interval for the slope includes 1.0 (0.85 to 1.69) and for the intercept it includes zero (−3.01 to 1.30 RBC/s). Effective vessel diameters of daughter vessels ranged from 4.8 – 6.1 μm with ratios between daughter vessel diameters between 1.0 and 1.2 (larger relative to smaller). Hemodynamic conditions within daughter branches were variable with mean tube hematocrits ranging from 5.6 ± 2.9 to 19.7 ± 3.7 % and cell velocities ranging from 52.3 ± 37.7 to 229.0 ± 61.1 μm/s.

Figure 4.

The fractional RBC distribution vs. fractional blood flow for one daughter branch of bifurcation H with varying hematocrit. The disproportionate distribution of cells follows the prediction of the empirical rule outlined in equation 4. Predicted values are based on the mean hematocrit over the collection period.

Figure 5.

Linear regression of measured supply rates in each daughter vessel vs supply rate predicted by the bifurcation rule given the appropriate flow rate measured in the parent vessel. N = 16 daughter vessels from 8 bifurcations.

Reconstructed Networks – Flow Model

Hemodynamic measurements for each vessel were compiled and indexed to the corresponding vessel in the 3D network. Cross sectional network red blood cell supply rate for networks 1 and 2 as measured from in vivo data were 47.9 and 38.3 RBCs/s respectively. Flow model solutions for each network yielded total RBC SR within < 0.1% of the corresponding measured values. Direct comparisons were made between the hemodynamic measurements and flow solution values on a vessel-by-vessel basis by utilizing indexed data for each 3D network. Figure 6 illustrates the difference in supply rate between the measured and modeled result for each vessel in the two test networks; vessels with no in vivo measurement are indicated in grey. The mean RBC supply rate difference per vessel was −1.6 ± 2.7 cells/s in network I and −0.7 ± 2.7 cells/s in network II, and the maximum absolute difference was 9.3 and 5.5 cells/s in network I and II, respectively. Despite these individual differences the total SR difference was less than 0.005 cells/s in both networks.

Figure 6.

Colormap of network I (top) and network II (bottom) showing the difference in supply rate in RBCs/s between in vivo measurements and the flow model result. Grey indicates that there were no in vivo measurements for comparison.

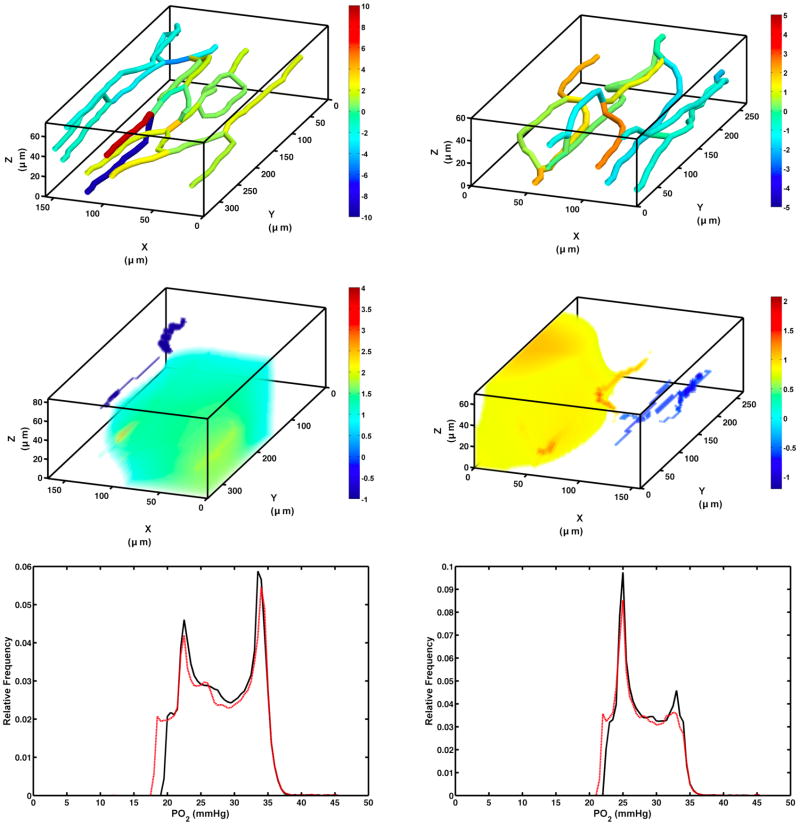

The flow solutions for the asymmetric case for the two networks were generated by increasing outlet pressure for capillaries on one side of the network while decreasing it for capillaries on the other side (inlet pressure was kept fixed). The goal was to maintain total SR to the network while varying RBC distribution asymmetrically such that SR increased by approximately 20% on one side of the network and decreased by 20% on the opposite side. Figure 7 (top panel) shows the difference of SR in the asymmetric cases in each capillary relative to the original flow model solution. Mean absolute difference in SR per capillary between the original and asymmetric perturbations were 27.6 ± 33.3% & 33.2 ± 40.1% in network I and network II, respectively.

Figure 7.

Top – RBC supply rate difference (cells/s) between the original solution and the asymmetrically perturbed flow solution for network I (left) and network II (right). Middle – Volumetric tissue PO2 difference map (mmHg) of the oxygen transport model for each network (only regions that have an difference greater than ± 1 mmHg are visible). Bottom – Relative distribution of PO2 in the tissue as determined by the oxygen transport model. Black curves represent the PO2 distributions for the original flow solutions while the red curves show the asymmetrically perturbed cases.

Reconstructed Networks – Oxygen Transport Model

Flow solutions for each network were applied to the O2 transport model. The resulting oxygen profiles in the volumes of interest were treated as controls against the transport models using the asymmetrically perturbed flow solutions. The oxygen transport simulations for the baseline flow solutions of networks I and II resulted in a mean tissue PO2 of 28.2 ± 4.8 mmHg and 28.1 ± 3.5 mmHg, respectively. For the asymmetrically perturbed cases, mean PO2 was 27.6 ± 5.17 mmHg and 27.7 ± 3.7 mmHg in networks I and II, respectively. The bottom panels of Figure 7 show the distribution of tissue PO2 for both cases in each network.

Resulting mean PO2 levels for the incremental changes in SRN are shown in Figure 8. Increasing supply rate by 10% resulted in a marginal increase in mean tissue PO2 of 4.0 and 3.4 % for networks I and II, respectively. Similarly, decreasing network supply rate by 10% produced decreases in mean tissue PO2 of 4.8 and 4.3 % in the two networks. Increasing SR by 40% only caused a mean tissue PO2 increase of 12.7 and 9.3 % in the networks whereas the SRN decrease of 40% lowered mean tissue PO2 by 29.1 and 29.6 % in networks I and II, respectively.

Figure 8.

Mean tissue PO2 changes predicted by the oxygen transport model for varying changes in SRN for networks I and II (error bars are the volume standard deviation).

DISCUSSION

We have described a systematic approach of using red blood cell supply rate to produce a flow solution that is representative of convective oxygen delivery conditions as observed in vivo. When combined with a 3D model of oxygen transport the use of red blood cell supply rate provides an excellent metric to use when attempting to accurately model oxygen levels within a 3D volume. By perturbing the original flow solutions and comparing results of the oxygen transport model, we were able to show that large supply rate differences in individual vessels did not result in similarly large differences in tissue PO2. This suggests that obtaining accurate inlet oxygen saturation measurements and representative total volume red blood cell supply rate are of paramount importance when modeling oxygen transport in complex networks. The specific distribution of cells within a discrete network does have an impact on oxygen delivery but our results suggest that diffusional exchange between vessels limits the impact of flow redistribution, provided that the overall supply rate remains constant. Small local changes in tissue PO2 are evident given the substantial redistribution of cells within the network (Top panel, figure 7), though the resulting change in tissue PO2 is relatively small (< 2% decrease in mean tissue PO2) compared to baseline solutions.

By applying mass balance on isolated bifurcations we were able to demonstrate that mean downstream measurements in daughter vessels over a 60 second period yield a value that is representative of direct measurements made over the same period in the parent vessels. While this result was not unexpected it is important to demonstrate that mean measurements of unsteady state flow are relevant to conditions elsewhere in the contiguous network.

Application of an empirical bifurcation rule (8) to predict red cell distribution at capillary branches did not prove to be entirely deterministic. Pries et al. indicated several potential reasons why experimental observations of flow distribution may not agree with the empirical prediction including irregularities in the vessel cross section, retardation of the plasma layer due to endothelial surface proteins and the presence of white blood cells (11). Furthermore, unsteady state flow produces constantly changing downstream conditions (blood flow rate, hematocrit and velocity) and creates inequitable discrepancies that confound efforts to accurately predict flow separation at bifurcations. This highlights the advantage of using measured SRN as a metric to compare flow solutions, as it less sensitive to local distribution variability.

Recent work by Benedict et al. (1) illustrates the potential utility of applying flow models to reconstructed microvascular networks in order to study the effect of specific pathologies. The present work presents the additional advantage of utilizing fully 3D network geometries and incorporating direct, vessel-by-vessel, hemodynamic measurements into a functional blood flow model.

We were able to demonstrate that substantial changes in total network supply rate do impact total tissue PO2. However, small changes in SRN only resulted in moderate alterations to mean tissue PO2 despite small heterogeneous spatial perturbations to PO2 distribution. Large decreases to SRN did substantially reduce mean tissue PO2 indicating the continued importance of accurate measurements of RBC supply rate in vivo. Experimental protocols need to focus first on ensuring that the best estimate of SRN is obtained before moving on to sample additional vessels.

CONCLUSION

Accurately quantifying blood flow in discrete vessels throughout a complex 3D capillary network remains a challenge. Currently it is not possible to make simultaneous measurements in all vessels of interest when a given network spans multiple fields of view, with vessels lying in numerous planes of focus. Further, the necessity of observing flow in each vessel for enough time to make accurate measurements of velocity, hematocrit and oxygen saturation, increases the time between individual vessel measurements thus exacerbating the problem of measuring unsteady flow in an inherently dynamic system. We believe that making serial measurements within individual vessels and utilizing total cross sectional red blood cell supply rate as a basis for determining an appropriate flow solution provides a result that represents flow conditions within the network as accurately as current technology will allow. We have shown that SRN provides a robust metric for quantifying blood flow in a discrete network, for the purposes of oxygen transport calculations, that is insensitive to errors in flow distribution and small perturbations in total RBC supply rate.

Perspectives.

Many pathological conditions (sepsis, diabetes, shock) result in impaired microvascular perfusion which affect tissue oxygenation. The approach outlined in the present work gives insights into how one should design experimental protocols for collecting the best data to model oxygen transport in these diseases. Models based on experimental measurements of capillary network 3D geometry, network SR and hemoglobin oxygen saturations at entrance and exit from the network can yield a better understanding of the impact of loss of capillary perfusion (sepsis, diabetes) or reduced flow on tissue oxygenation.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This project was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP 102504 (C.G. Ellis) and the National Institute of Health HL089125 (D. Goldman & C.G. Ellis).

References

- 1.Benedict KF, Coffin GS, Barrett EJ, Skalak TC. Hemodynamic Systems Analysis of Capillary Network Remodeling During the Progression of Type 2 Diabetes. Microcirculation. 2010;18:63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis CG, Ellsworth ML, Pittman RN, Burgess WL. Application of image analysis for evaluation of red blood cell dynamics in capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1992;44:214–225. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(92)90081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser GM, Milkovich S, Goldman D, Ellis CG. Mapping 3-D functional capillary geometry in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H654–664. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01185.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman D, Popel AS. Computational modeling of oxygen transport from complex capillary networks. Relation to the microcirculation physiome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;471:555–563. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4717-4_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japee SA, Ellis CG, Pittman RN. Flow visualization tools for image analysis of capillary networks. Microcirculation. 2004;11:39–54. doi: 10.1080/10739680490266171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japee SA, Pittman RN, Ellis CG. A new video image analysis system to study red blood cell dynamics and oxygenation in capillary networks. Microcirculation. 2005;12:489–506. doi: 10.1080/10739680591003332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pries A, Secomb T, Gaehtgens P. Biophysical aspects of blood flow in the microvasculature. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:654–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pries AR, Ley K, Claassen M, Gaehtgens P. Red cell distribution at microvascular bifurcations. Microvasc Res. 1989;38:81–101. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pries AR, Neuhaus D, Gaehtgens P. Blood viscosity in tube flow: dependence on diameter and hematocrit. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1770–1778. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pries AR, Schönfeld D, Gaehtgens P, Kiani MF, Cokelet GR. Diameter variability and microvascular flow resistance. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2716–2725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P, Gross JF. Blood flow in microvascular networks. Experiments and simulation. Circulation Research. 1990;67:826–834. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gessner T, Sperandio MB, Gross JF, Gaehtgens P. Resistance to blood flow in microvessels in vivo. Circulation Research. 1994;75:904–915. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyml K, Mathieu-Costello O, Budreau CH. Distribution of red blood cell velocity in capillary network, and endothelial ultrastructure, in aged rat skeletal muscle. Microvasc Res. 1992;44:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(92)90097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wetter T, Hoffmann D, Schmid-Schönbein H. Analysis of network flow distribution: computational aid to minimize experimental expenditure. Microvasc Res. 1983;26:221–237. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(83)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]