Abstract

Purpose

Teenage pregnancy and marijuana use are associated with higher risk of contracting Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). In this study, we examined the role of early and current marijuana use as it related to STI risk in a sample of young women who were pregnant teenagers, using a variety of statistical models.

Methods

279 pregnant adolescents, ages 12–18, were recruited at an urban prenatal clinic as part of a study that was developed to evaluate the long-term effects of prenatal substance exposure. Six years later, they were asked about their substance use and sexual history. The association of early and late marijuana use to lifetime sexual partners and STIs was examined, and then structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to illustrate the associations among marijuana use, number of sexual partners, and STIs.

Results

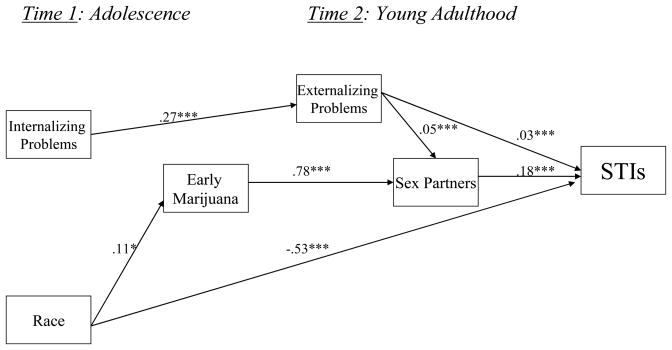

Bivariate analyses revealed a dose-response effect of early and current marijuana use on STIs in young adulthood. Early and current marijuana use also predicted a higher number of lifetime sexual partners. However, the effect of early marijuana use on STIs was mediated by lifetime number of sexual partners in the SEM, whereas African-American race, more externalizing problems, and a greater number of sexual partners were directly related to more STIs.

Conclusions

Adolescent pregnancy, early marijuana use, mental health problems, and African-American race were significant risk factors for STIs in young adult women who had become mothers during adolescence. Pregnant teenage girls should be screened for early drug use and mental health problems, because they may benefit the most from the implementation of STI screening and skill-based prevention programs.

Compared to other developed countries, American 15–19 year olds have one of the top three highest reported rates of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia (Panchaud, Singh, Feivelson, & Darroch, 2000). Within the US adolescent population, girls (especially African-American girls) are at higher risk of contracting a sexually-transmitted infection (STI) than boys (Aral & Holmes, 1990; Bunnell et al., 1999; CDC, 2005; Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2000). Although all sexually-active girls are vulnerable to STIs, those who become teenage mothers are a particularly high-risk subset within this age group (Boyer, Shafer, Wibbelsman, Seeberg, Teitle, & Lovell, 2000; Ethier, Kershaw, Niccolai, Lewis, & Ickovicks, 2003; Meade & Ickovicks, 2005). For example, Ickovics et al. (2003) conducted a prospective cohort study of pregnant 14–19 year olds and reported that they are twice as likely to become infected with chlamydia or gonorrhea than non-pregnant peers.

Marijuana is the most prevalent illicit drug used by American adolescents, with a third of tenth-graders reporting use in the last year. Marijuana is the only drug that African-American youth use at a rate comparable to Caucasian youth (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2006), and several recent studies have linked marijuana use to STIs among sexually-active African-American girls (Boyer, Sebro, Wibbelsman, & Shafer, 2006; Crosby et al., 2002; Liau et al., 2002). Research suggests that although pregnant adolescents may reduce substance use during pregnancy (Flanagan & Kokotailo, 1999; Gillmore, Gilchrist, Lee, &Oxford, 2006) their use increases after pregnancy and does not decline during the transition to adulthood (Gilchrist, Hussey, Gillmore, Lohr, & Morrison,1996; Gillmore et al., 2006). Therefore, increased use of marijuana may be one pathway of risk for STIs in this more vulnerable group of girls.

Marijuana could impact STI risk in girls through changes in sexual behavior including disinhibition (Kandel & Chen, 2000), multiple and concurrent sexual partners, or widening social networks to include riskier sexual partners. Alternatively, marijuana and risky sexual behavior could be linked by common personality traits or a syndrome of deviance, as suggested by problem behavior theory (Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Jessor, 1991; Jessor & Jessor, 1978).

Problem behavior theory states that due to the social ecology of youth, involvement in a problem behavior such as illicit drug use increases the likelihood that a child will become involved in another problem behavior, such as sexual risk-taking. The theory also proposes a system of checks and balances, in which conventional behaviors such as church attendance and school achievement serve to involve youth in the larger societal network, and can act as protective factors. Furthermore, the model predicts “transition proneness,” in which youth who engage in one problem behavior ahead of age-graded norms are more likely to transition into another problem behavior ahead of peers. Therefore, earlier initiation of a problem behavior such as marijuana use denotes higher risk (Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Jessor, 1991; Jessor & Jessor, 1978).

Other authors have provided evidence that internalizing problems (negative affect and social withdrawal) and externalizing problems (deviance and “acting out” behaviors related to problem behavior theory) may be separate pathways to substance abuse (Chassin & Ritter, 2001) and sexual risk-taking (Donenberg & Pao, 2005) during adolescence. More prospective, longitudinal research is needed to better understand the relationships among early substance use, psychosocial problems and STIs, especially in high-risk groups of girls. Although there is a small body of research examining substance use and STIs, few studies have prospectively examined marijuana use and other correlates of STIs among pregnant and mothering teenagers, and even fewer have used multivariate analyses to test associations while adjusting for potential confounds (Meade & Ickovicks, 2005).

The present study was designed to address some of the shortcomings in the literature, and to compare the antecedent and concurrent predictors of number of lifetime partners and STIs in young adults who were teenage mothers. We hypothesized that young mothers who initiated marijuana use at an earlier age would have more lifetime sex partners and STIs than other young mothers from the same high-risk sample, consistent with problem behavior theory. Young mothers who currently used more marijuana were also expected to have more lifetime sex partners and STIs. However, we hypothesized that early use of marijuana would predict more lifetime number of partners and STIs, even after controlling for current marijuana use and other psychosocial variables.

Method

Study sample

Participants in this study were part of a larger, ongoing cohort study that sought to determine the long-term effects of prenatal substance use in the offspring of pregnant teenagers. Detailed methods of the study have been published previously (Cornelius, Goldschmidt, Day, & Larkby, 2002). Pregnant adolescents (12–18 years old) were recruited from an outpatient prenatal clinic (Time 1) at an inner-city teaching hospital associated with the University of Pittsburgh. All pregnant girls under age 19 who attended the prenatal clinic were eligible for the study, and only 3 of the 448 adolescents who were approached for the study refused to participate (initial refusal rate = 0.7%). Of the 445 teenagers enrolled in the study, 15 subsequently moved out of the area, 1 refused a delivery interview, and 16 did not give birth to a live, singleton pregnancy. The remaining 413 were assessed at birth and contacted for follow-up 6 years later (Time 2). Six years of age was considered an optimal age to reliably assess the cognitive and neurobehavioral status of the offspring, and marks an important stage in child development (transition to school). Although the larger study was not designed to examine STI risk among the mothers, additional funding was received to examine their sexual histories which allowed us to examine risk for STIs in this highly vulnerable group, and to examine correlates of that risk using other data collected from the larger project. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh approved each phase of the study protocol.

At the six-year follow-up, 334 women and their children were seen. The current study resulted from additional funding that was received to comprehensively examine the sexual history of this sample. However, this funding was not received until after the original follow-up testing began, when some women had already been assessed. Therefore, the present study is based on the remaining 279 women in the sample who received the sexual history questionnaire (86% of the original 334 seen at both time points). At the six-year postpartum phase, 10 mothers refused to participate, 25 were lost to follow-up, 9 had moved out of the state, and 5 children were in foster placement. In addition, there had been 6 child deaths and 1 child was adopted. Prenatal substance exposure and demographic characteristics were not significantly different between the 56 children who were not assessed and the remaining children who were assessed (Cornelius, Goldschmidt, De Genna, & Day, 2007).

Most (75%) of the subsample was African-American, and the remainder were Caucasian. Participants’ average age was 16.32 years (SD = 1.26) at Time 1, and 23.22 years (SD = 1.42) at Time 2. Although one-third of the teenagers dropped out of school while pregnant, only 18% reported that they had completed less than 12 years of education by Time 2, suggesting that many of the adolescent mothers had either returned to school or completed a GED. At Time 1, 72% of the adolescents were primagravidas and only 3 were married, whereas 88% had been pregnant at least twice by Time 2 and 17% of the sample were married.

Data collection

The data for this study come from the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development Project (MHPCD), a consortium of projects that evaluate the long-term effects of prenatal substance exposure. The recruitment, prenatal, and delivery phases of this study occurred between 1990 and 1994. These phases took place at the Magee-Women’s Hospital, the teaching hospital for the departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Neonatology of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Time 1 data were collected during interviews with pregnant teenagers in a private room at the prenatal clinic of an urban teaching hospital, after assuring confidentiality and obtaining informed consent. Demographic information and data on the participants’ substance use, physical and mental health were obtained during the initial wave of testing (Time 1). The six-year follow-up of the participants and their offspring (Time 2) took place at the MHPCD offices (in the same neighborhood as the teaching hospital) between 1996 and 2000.

Measures

Dependent variables

At Time 2, participants provided information about their lifetime number of sexual partners (M = 6.54, SD =4.95) and lifetime diagnoses of STIs (M =0.87, SD = 1.14). Lifetime number of sex partners was determined by asking, “How many people have you ever had vaginal sexual intercourse with?” The number given was used as an outcome in hierarchical regression analyses, but was also recoded into 4 categories using quartiles for the path model analyses (1= 1–3 sex partners, 2 = 4–5 sex partners, 3 = 6–8 sex partners, 4 = 9+ sex partners). STI history was determined by asking, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or a nurse that you have…?” followed by a list of possible STIs. Self-reported STIs are sometimes subject to under-reporting, but several recent studies suggest that self-report is a cost-effective and reliable method of data collection (Niccolai, Kershaw, Lewis, Cicchetti, Ethier, & Ickovicks, 2005). Almost half (45%) of the young mothers who had gotten pregnant as teenagers reported being diagnosed with chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital warts, trichimonas, herpes, and/or pubic lice (range = 0–4 separate diagnoses). Due to the high prevalence of multiple STIs in this sample, an ordinal level variable was created: no STIs diagnosed by Time 2 (55% of the sample), 1 STI diagnosed (21% of the sample), 2+ STIs diagnosed (24% of the sample).

Independent Variables

The independent variables in this study were the early initiation and current use of marijuana. If the participants reported trying marijuana, interviewers asked about age at initiation and current usage. We used a cut-off of age 15 to create an “early initiation” variable because data suggest that only one-third of high-school students have tried marijuana by tenth-grade (Johnston et al., 2006). After excluding all adolescent mothers who entered the study before age 15 (n = 24), 18% of the remaining sample had used marijuana before age 15, and were therefore considered early users. At Time 2, participants were asked again if they had ever smoked marijuana, and if they responded positively, they were asked to estimate how often (using a calendar) and how much was used in the past year. Quantity and frequency of the usual, maximum, and minimum use of marijuana was assessed. This information was used to calculate an average daily joints of marijuana, hashish, and sensimilla. A blunt of marijuana was converted to four joints and a hashish cigarette or bowl was counted as three joints, based on the relative amount of delta-9-THC in each (Gold, 1989). Gillmore et al., (1996) reported that nearly 20% of the young women who were adolescent mothers in their sample used marijuana 6 years after a teenage pregnancy, and marijuana use in our sample was comparable: 23% used marijuana in the past year.

Covariates

We also assessed demographic, psychological, and marijuana-associated variables that could mediate the relationship between marijuana use and sexual health outcomes, based on previous research (Billy, Brewster, & Grady, 1994; Meade & Ickovicks, 2005; Sionean et al., 2001). Information obtained at baseline included age, race, age at menarche, and the educational levels attained by the adolescent participant and her mother. Twenty-seven of the teenage mothers reported that they did not know their mothers’ level of educational attainment: mean replacement was used in these cases. Monthly family income was obtained at Time 2, and a square-root transformation was used on this variable because of significant positive skew. The participants’ mother’s level of education was used as a proxy for SES at Time 1, whereas her own monthly family income was used at Time 2.

Two psychosocial variables included as covariates were participant t-scores for externalizing problems (e.g., disobeying parents and teachers, cheating, destroying property, lying) and internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, physical symptoms without medical cause, fear). Two widely-used, developmentally-appropriate, normed and reliable instruments were used to assess internalizing and externalizing problems: the Youth Self-Report (YSR: Achenbach, 1991) was used at Time 1 and the Young Adult Self-Report (YASR: Achenbach, 1997) was used at Time 2. The YSR and YASR measure adaptive functioning and emotional and behavioral problems experienced in the past 6 months using items that are scored on a three-point scale : 0=not true; 1=somewhat or sometimes true; 2=very true or often true. Time 1 internalizing scores were compiled from the anxious/depressed (16 items), somatic complaints (9 items), and withdrawn subscales (7 items) of the YSR. Time 2 internalizing scores were derived from the anxious/depressed (17 items) and withdrawn subscales (7 items) of the YASR. For externalizing scores, the YSR at Time 1 included the combined aggression (19 items) and delinquent (11 items) subscales whereas the YASR at Time 2 included the Intrusive (7 items), Aggressive (12 items), and Delinquent subscales (9 items).

Church attendance was also included in regression models as a proxy for religiosity, because religiosity has been demonstrated to protect adolescents from both substance abuse and sexual risk (Miller, Davies, & Greenwald, 2000; Resnick et al., 1997). Church attendance was assessed with one item at both time points: “How often do you go to church?” Answers were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “more than once a week.” Additional marijuana-associated measures obtained at Time 1 included an assessment of peer marijuana use, in which participants reported on whether all, most, some, or none of their friends used marijuana. At Time 2, the 119 participants who were married or living with a male partner were asked if their husband or live-in boyfriend had or ever had a problem with alcohol and/or drugs. This was used to create a dichotomous covariate: partner ever/never had an alcohol/drug problem.

Statistical Analyses

Three levels of statistical analysis were conducted using SPSS 13.0 for Windows (Norusis, 2005). First, bivariate analyses using the χ2 test of differences in proportions examined the relations between the independent variables (early initiation of marijuana, current use of marijuana) and the three-category outcome of lifetime diagnoses of STIs. Next, two sets of multiple regressions were utilized to test the independent, predictive value of marijuana use on the sexual history outcomes: lifetime number of sexual partners and lifetime diagnoses of STIs. The first set of regressions tested longitudinal predictors of young mothers’ sexual risk (i.e., from Time 1 predictors to Time 2 outcomes). The second set of regressions tested cross-sectional predictors of young mothers’ sexual risk (i.e., examining independent and dependent variables from Time 2).

Independent variables were entered into the regression analyses in 3 separate steps, in order to consider the unique contributions of each domain in turn. First, we included demographic covariates (participants’ age, race, and SES). Second, we included psychosocial covariates (age at menarche, church attendance, and externalizing and internalizing problems). Finally, marijuana use variables were entered in the last step of each regression, including early use of marijuana and peer use of marijuana at Time 1, and average daily marijuana joints and partner’s ever/never problem with alcohol and drugs at Time 2.

Structural equation modeling (LISREL 8: Joreskog & Sörbom, 1993) was utilized in the final stage of analyses to assess a conceptual path model for the effects of marijuana use and lifetime number of partners on STIs in young adults who were teenage mothers. Structural equation modeling is useful for testing a priori hypotheses, and is also model-generating, in that insignificant paths can be removed until the most parsimonious model for STIs has been identified. Moreover, it is one of the most inclusive statistical practices currently used in the behavioral sciences, containing elements of techniques such as ANOVA and multiple regression that may be more familiar to clinicians (Kline, 2005). Finally, the structural equation yields a visual that can help health care providers quickly and easily identify risk factors for STIs.

Results

Bivariate results

Consistent with national surveillance data (CDC, 2005; Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2000), African-Americans in this sample were significantly more likely to report having been infected with gonorrhea (18% vs 3%), chlamydia (42% vs 16%), pubic lice (13% vs 3%) and trichomonas (24% vs 7%) than Caucasians. The zero-order correlation between lifetime number of sex partners and number of STIs reported by Time 2 was r = .315 (p < .001). The results of cross-tabulations on marijuana usage at both time points and reported number of STI diagnoses are presented in Table 1. Almost sixty percent of the young women who had initiated marijuana use by age 15 had ever had a STI diagnosis, compared to 42% of the young women who did not use marijuana at an early age. The results of a cross-tabulation of Time 2 marijuana and reported number of STI diagnoses suggest a dose-response effect. Only 20% of the non-users had 2 or more STIs diagnosed by young adulthood, whereas 35% of the light users and 64% of the heavy users had 2 or more STIs.

Table I.

Lifetime diagnoses of STIs as a function of Marijuana Usage (unadjusted)

| No STI diagnoses | 1 STI diagnosis | 2+ STI diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | |||

| No early use of Marijuana (n = 204) | 58% | 21% | 21% |

| Early use of Marijuana (n = 46) (χ2 = 5.82, p < .05) | 41% | 22% | 37% |

| Time 2 | |||

| No Marijuana Use (0 average daily joints: n = 214) | 57% | 23% | 20% |

| Light Marijuana Use (< 1joint/day: n = 43) | 48% | 18% | 35% |

| Heavy Marijuana Use (1+ joints/day: n = 22) (χ2 = 22.39, p < .001) | 27% | 9% | 64% |

Multiple regression results

The results of the multiple regressions from the longitudinal (from adolescence to young adulthood) and cross-sectional data (young adulthood) on lifetime number of sex partners are presented in Table 2. Early initiation of marijuana was the strongest longitudinal predictor of lifetime number of sexual partners in young adulthood in women who were teenage mothers, and the final model accounted for 12% of the variance in the number of sexual partners (F = 4.72, p < .001). More externalizing problems and current use of marijuana significantly predicted more sexual partners in the cross-sectional model, which accounted for 16% of the variance in number of sexual partners by young adulthood (F = 6.80, p < .001).

Table II.

Final Models of Hierarchical Regressions on Lifetime Sex Partners (n = 279)

| Statistics for Individual Predictors in the Final Model | Step Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Beta | t | R2 change | F change | |

| Time 1 (Longitudinal Model) | ||||

| Age at entry into study | −.04 | −0.67 | .01 | 1.02 |

| Race | −.01 | −0.20 | ||

| SES (adolescent’s mother’s education) | .03 | 0.56 | ||

| Age at menarche | .03 | 0.44 | .06 | 3.77** |

| Frequency of church attendance | −.09 | −1.50 | ||

| Externalizing problems | .08 | 1.00 | ||

| Internalizing problems | .14 | 1.82t | ||

| Early Marijuana use | .30 | 4.73*** | .08 | 11.33*** |

| Friends use marijuana | −.05 | −0.71 | ||

| Time 2 (Cross-sectional Model) | ||||

| Age | −.07 | −1.15 | .01 | 0.75 |

| Race | −.01 | −0.14 | ||

| Educational attainment | .02 | 0.30 | ||

| Income | .06 | 0.91 | ||

| Frequency of church attendance | −.11 | −1.89t | .16 | 16.47*** |

| Externalizing problems | .24 | 2.82** | ||

| Internalizing problems | .13 | 1.62 | ||

| Average daily joints used at Time 2 | .15 | 2.43* | .02 | 3.62* |

| Household male has/had alcohol/substance abuse problem | .06 | 1.00 | ||

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

The results of the ordinal regressions from the longitudinal and cross-sectional data on number of STIs reported by Time 2 are presented in Table 3. Race, SES, and higher scores on the internalizing scale were significant longitudinal predictors of STIs: African-American teenagers, teenage girls whose own mothers had less education, and girls who reported more internalizing problems had been infected with more STIs by Time 2. Early initiation of marijuana was also a significant longitudinal predictor of STIs, even after accounting for other covariates at Time 1 (χ 2= 59.94, p < .001; Cox & Snell R2 = .21). In the model using cross-sectional data from Time 2, African-Americans and women with more externalizing problems had more STI diagnoses. However, after controlling for race and externalizing problems, current marijuana use remained a significant predictor of number of STIs in these young women (χ 2= 68.82, p < .001; Cox & Snell R2 = .23).

Table III.

Final Models of Ordinal Regressions on Reported STI Diagnoses (n = 279)

| Estimate | Standard Error | Wald | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 (Longitudinal Model) | ||||

| Age at entry into study | −0.22 | .14 | 2.37 | −0.49 – 0.06 |

| Race | −1.62 | .33 | 24.06*** | −2.27 – −1.00 |

| SES (adolescent’s mother’s education) | −0.31 | .10 | 9.41** | −0.51 – −0.11 |

| Age at menarche | 0.15 | .10 | 2.32 | −0.04 – 0.34 |

| Frequency of church attendance | −0.07 | .09 | 0.60 | −0.24 – 0.11 |

| Externalizing problems | 0.01 | .02 | 0.20 | −0.03 – 0.04 |

| Internalizing problems | 0.06 | .02 | 7.29** | 0.02 – 0.10 |

| Early Marijuana use | 1.01 | .36 | 7.91** | 0.31 – 1.71 |

| Friends use Marijuana | 0.19 | .14 | 1.80 | −0.09 – 0.46 |

| Time 2 (Cross-sectional Model) | ||||

| Age | −0.22 | .10 | 5.03* | −0.41 – −0.03 |

| Race | −1.32 | .32 | 17.13*** | −1.95 – −0.70 |

| Educational attainment | −0.10 | .10 | 1.14 | −0.30 – 0.09 |

| Income | 0.08 | .32 | 0.07 | −0.55 – 0.71 |

| Frequency of church attendance | −0.09 | .09 | 0.97 | −0.26 – 0.09 |

| Externalizing problems | 0.04 | .02 | 3.96* | 0.00 – 0.07 |

| Internalizing problems | 0.03 | .02 | 2.25 | −0.01 – 0.07 |

| Average daily joints used at Time 2 | 0.31 | .16 | 3.89* | 0.00 – 0.61 |

| Household male alcohol/substance abuse problem | −0.33 | .54 | 0.37 | −1.38 – 0.72 |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Structural Equation Model

Structural equation modeling with LISREL 8.5.1 was used as a final step to evaluate a more comprehensive longitudinal and mediational model on the effects of race, marijuana, and sexual risk activity on STIs in young women who were teenage mothers. The adolescent’s mother’s level of education was initially included to control for the teenage girls’ SES, and current marijuana use was included to test for cross-sectional effects of marijuana use. However, both of these variables were removed because no paths including them were statistically significant. Goodness-of-fit indices indicate that the final model has a good fit, accounting for 22% of the total variance in reported diagnoses of STIs by Time 2 (Figure 1). Although early marijuana use was a significant predictor of STIs in the multiple regression analyses, it is clear from the path model that its effects are mediated by number of lifetime sex partners. Race continued to predict directly STIs in women who had been teenage mothers: consistent with national samples, African Americans were at higher risk. However, Caucasian adolescents were more likely to have initiated marijuana use before age 15, and earlier initiation of marijuana predicted more lifetime sex partners, also placing these mothers at-risk of contracting more STIs.

Figure 1.

Path model predicting STI diagnoses in young women who were pregnant teenagers (n = 279) χ2= 16.70, p = .12; RMSEA = .04; NFI = .92, CFI = .97

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study that examines the associations between early and current marijuana use and risk for reported STIs in an urban community sample of teenage mothers, while controlling for several demographic and psychosocial factors. Bivariate analyses suggested a dose-response effect of current marijuana use on STIs, and subsequent multivariate analyses were generally consistent with our other hypotheses. Adolescent mothers who had initiated marijuana at a younger age as well as young adult mothers who currently used more marijuana were at higher risk for STIs. However, by pitting early and current marijuana use against each other and against lifetime sex partners in a structural equation model, we were able to learn that early marijuana use was a better predictor of sexual risk than elevated current marijuana use, and that the effect of early marijuana use on risk for increased STIs was mediated by lifetime number of sex partners.

Our finding that early-onset marijuana predicted a greater number of lifetime sexual partners was consistent with findings from a cross-sectional study of drug use and sexual risk-taking in high-school students (Shrier, Emans, Woods, & DuRant, 1996). Although Halpern and colleagues (2004) found that substance use does not necessarily covary with sexual risk-taking in young African-American females, several cross-sectional studies have linked concurrent marijuana use to STIs in similar samples (Boyer et al., 2000; Crosby et al., 2002; Liau et al., 2002). Our use of both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses as well as a path model may help explain some of the discrepancies reported in the literature. Caucasian teenage mothers were more likely than African-American teenage mothers to have used marijuana by age 15, and the path model demonstrated a pathway between early marijuana use and STIs through increased number of sexual partners by young adulthood.

Although Caucasian adolescent mothers in our study were more likely to initiate marijuana at an early age, and this early initiation was associated with more sex partners, African-American race directly predicted more STIs in the path model. Consistent with our finding that lifetime number of sex partners was only one pathway to risk for STIS, Bunnell et al. (1999) found that 30% of urban female adolescents with only 1 lifetime partner were found to have an STI during a visit to a teen clinic for an annual checkup or to start birth control. Some authors (Franks et al., 2006) postulate that the higher burden of disease associated with African-American race in the US can largely be explained by SES (which was not significant in our path model) and racism. Several studies have demonstrated the effects of residential segregation, racism and perceived racism on physical health (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Kunitz & Pesis-Katz, 2005), trust in physicians (Bird & Bogart, 2001; Doescher, Saver, Franks, & Fiscella, 2000), and negative attitudes towards contraception (Thorburn & Bogart, 2005). Other researchers have attempted to explain racial/ethnic group differences in sexual risk with measures of neighborhood poverty and collective efficacy (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004). Finally, epidemiologists have examined differences in sexual contact networks (e.g., more dissortative mating and concurrent relationships) that may help explain differences in exposure to STIs (Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005; Laumann & Youm, 1999; Turner, Garnett, Ghani, Sterne, & Low, 2004).

The multivariate analyses also revealed the importance of maladaptive functioning (internalizing and externalizing problems) in predicting risk for STIs among women who were teenage mothers. These results were consistent with previous studies linking mental health problems to risky sexual behavior in adolescence (Brown, Danovsky, Lorie, DiClemente, & Ponton, 1997; Tubman, Windle, & Windle, 1996) and adulthood (Meade, 2006; Tubman, Gil, Wagner, & Artigues, 2003). Externalizing problems in young adulthood were associated with multiple STIs, both directly and indirectly (through more lifetime sexual partners). The path model suggests that externalizing problems in young adulthood were predicted by internalizing problems in adolescence, rather than continuity of internalizing or externalizing symptoms across this period. This finding is interesting in light of findings that childhood internalizing problems may be protective for health-risk behaviors in adolescence and adulthood (De Genna, Stack, Serbin, Ledingham, & Schwartzman, 2006; De Genna, Stack, Serbin, Schwartzman, & Ledingham, in press; Tubman et al., 1996). However, other studies have demonstrated an association of internalizing problems with sexual risk via decreased assertiveness, earlier sexual initiation, more sexually active friends, and less ability to negotiate safe sex and other sexual demands (Brooks-Gunn & Paikoff, 1997; Donenberg & Pao, 2005; Jordan & Donenberg, 2006; Whitbeck, Conger & Kao, 1993). Although girls with externalizing problems may be easier to identify in our clinics and classrooms, these findings suggest that pregnant girls suffering from internalizing problems may also be at-risk for multiple STIs by young adulthood.

Limitations

Although this is one of the first studies to systematically and longitudinally examine predictors of sexual risk and STIs in adolescent mothers using multivariate techniques, there were several limitations which should be addressed in future research. One limitation was that number of sexual partners was only assessed at Time 2, and it is possible that some teenage mothers may have had many sexual partners before age 15, and then been abstinent or had fewer partners in late adolescence and early adulthood. However, Meade and Ickovick’s (2005) finding that teenage mothers are more likely to get pregnant or contract STIs than other adolescents suggests that they were not as likely to have been abstinent in this period. The analyses also relied on self-report data, including self-report of an illegal activity (use of marijuana) and data of a sensitive nature (i.e., lifetime number of sexual partners, STIs). However, participants were assured of confidentiality and, although one study has found that self-report may under-estimate STI prevalence in African-American teenagers (Harrington et al., 2001), other studies have shown that self-report data for sexual behavior are consistent with biological markers and medical records (e.g., Niccolai et al., 2005). Another limitation was the uneven distribution of pregnant adolescents by race, which reflected the racial distribution at the prenatal clinic of the inner-city teaching hospital (for pregnant teenagers who do not terminate their pregnancies and who seek prenatal care). Therefore, there were fewer Caucasian teenage mothers for purposes of comparison. Nonetheless, the epidemic rates of STIs in this sample and in young African-American women in general, merit further investigation of the risk factors for exposure in this high-risk group.

Conclusions

One of the most valuable contributions of this study is the use of both cross-sectional and longitudinal models, which were crucial in distinguishing which variables were associated with multiple partners and infections at both time points, and highlight the value of prospective cohort studies. Early marijuana use was associated with more sexual partners by young adulthood, suggesting that early substance users are at especially high-risk for STIs, even within this vulnerable sub-group of girls. Internalizing problems (e.g. anxiety, depression, and withdrawal) were also early markers of problems by young adulthood: this was associated with more externalizing problems, a risk factor for more sexual partners and STIs in this sample. Finally, African-American race remained a significant predictor of STIs in our multivariate models, even after controlling for many individual-level variables. More research to address racial disparities in STDs is clearly warranted.

The high prevalence of STIs in this sample of young women who were teenage mothers is consistent with the literature on adolescent pregnancy, and supports assertions that teenage pregnancy is a marker for increased future sexual risk--these girls are more likely to continue to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse that may lead to unplanned pregnancies and STIs (Ickovicks et al., 2003; Meade & Ickovicks, 2005). Therefore, it is crucial that the health care providers that come into contact with adolescents and young mothers are aware of this heightened risk and aggressively screen for drug use and mood disorders. This may require improved screening methods to identify drug use (such as marijuana) and psychological problems (such as anxiety or depression), as well as effective interventions to address them.

Acknowledgments

Young Shim Jhon, Lidush Goldschmidt and Sharon Leech provided invaluable assistance with data management and statistical analyses. The authors would also like to thank the young women who made this study possible by contributing their time and candidly sharing their experiences with our interviewers and field staff.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA 009275 PI: MC) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA 08284 PI: MC). ND was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, (NIAAA T32 07453 PI: MC) as well as the University of Pittsburgh.

Young Shim Jhon, Lidush Goldschmidt and Sharon Leech provided invaluable assistance with data management and statistical analyses. The authors would also like to thank the young women who made this study possible by contributing their time and candidly sharing their experiences with our interviewers and field staff.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Marie D. Cornelius, Email: mdc1@pitt.edu.

Robert L. Cook, Email: cookrl@phhp.ufl.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191:S115–122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, Holmes KK. Epidemiology of sexual behavior and sexually transmitted diseases. In: Holmes KK, Mardh PA, Weisner P, et al., editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2. New York: McGraw Hill; 1990. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Billy JOG, Brewster KL, Grady WR. Contextual effects on the sexual behavior of adolescent women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff R. Sexuality and Developmental Transitions during Adolescence. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelman K, editors. Health risks and developmental trajectories during adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Danovsky MB, Lorie KJ, DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE. Adolescents with psychiatric disorders and the risk of HIV. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell RE, Dahlberg L, Rolfs R, Ransom R, Gershman K, Farshy C, Newhall WJ, Schmid S, Stone K, St Louis M. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in urban adolescent females despite moderate risk behaviors. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1999;80:1624–1631. doi: 10.1086/315080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer CB, Sebro NS, Wibbelsman C, Shafer MA. Acquisition of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents attending an urban, general HMO teen clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(2):287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Wibbelsman CJ, Seeberg D, Teitle E, Lovell N. Associations of sociodemographic, psychosocial and behavioral factors with sexual risk and sexually transmitted diseases in teen clinic patients. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:102–111. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2004. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Ritter J. Vulnerability to Substance Abuse Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. In: Ingram RE, Price JM, editors. Vulnerability to Psychopathology: Risk Across the Lifespan. Guilford Press; New York City: 2001. pp. 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, Day N, Larkby C. Prenatal substance use among pregnant teenagers: A six-year follow-up of effects on offspring growth. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2002;24:703–710. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, De Genna N, Day N. Smoking during teenaged pregnancies: Effects on behavioral problems in offspring. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9:739–750. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington K, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, Oh MK. Predictors of infection with Trichomonas vaginalis: A prospective study of low income African-American adolescent females. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78:360–364. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.5.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Stack DM, Serbin LA, Ledingham J, Schwartzman AE. From healthy behaviour to health-risk: Continuity across two generations. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:297–309. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Stack DM, Serbin LA, Schwartzman AE, Ledingham J. Maternal and child health problems: The inter-generational consequences of early maternal aggression and withdrawal. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:2417–2426. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:1156–1163. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier KA, Kershaw T, Niccolai L, Lewis JB, Ickovics JR. Adolescent women underestimate their susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:408–411. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.5.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg G, Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry’s role in a changing epidemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;58:890–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan P, Kokotailo P. Adolescent pregnancy and substance use. Clinical Perinatology. 1999;26(1):185–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P, Muennig P, Lubetkin E, Jia H. The burden of disease associated with being African-American in the United States and the contribution of socio-economic status. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:2469–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist LD, Hussey JM, Gillmore MR, Lohr MJ, Morrison DM. Drug use among adolescent mothers: Prepregnancy to 18 months postpartum. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;19(5):337–344. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Gilchrist LD, Lee J, Oxford ML. Women who gave birth as unmarried adolescents: Trends in substance use from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. Marijuana. Plenum Publishing Company; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Hallfors D, Bauer DJ, Iritani B, Waller MW, Cho H. Implications of racial and gender differences in patterns of adolescent risk behavior for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Perspectives on Sex and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:239–247. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.239.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington KF, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Person S, Oh MK, Hook EW., 3rd Validity of self-reported sexually transmitted diseases among African American female adolescents participating in an HIV/STI prevention intervention trial. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(8):468–471. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200108000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, Kershaw TS, Ethier KA. High postpartum rates of sexually transmitted infections among teens: Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:469–473. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:507–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Theory testing in longitudinal research on marijuana use. In: Kandel D, editor. Longitudinal Research on Drug Use. Washington, D.C: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2005. (NIH Publication No. 06-5882) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Donenberg GR. Child and adolescent psychiatry and HIV/AIDS. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. 2006;18:545–550. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245356.68207.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog K, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Chen K. Types of marijuana users by longitudinal course. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:367–378. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ, Pesis-Katz I. Mortality of white Americans, African Americans, and Canadians: The causes and consequences for health of welfare state institutions and policies. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83:5–39. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: A network explanation. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liau A, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Williams KM, Harrington K, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, Oh MK. Associations between biologically confirmed marijuana use and laboratory-confirmed sexually transmitted diseases among African American adolescent females. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:387–390. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS. Sexual risk behavior among persons dually diagnosed with severe mental illness and substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse and Treatment. 2006;30(2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Ickovics JR. Systematic review of sexual risk among pregnant and mothering teens in the USA: Pregnancy as an opportunity for integrated prevention of STI and repeat pregnancy. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:661–678. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Davies M, Greenwald S. Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(9):1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccolai LM, Kershaw TS, Lewis JB, Cicchetti DV, Ethier KA, Ickovics JR. Data collection for sexually transmitted disease diagnoses: A comparison of self-report, medical record reviews, and state health department reports. Annuals of Epidemiology. 2005;15:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis M. SPSS 13.0 Statistical Procedures Companion. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Panchaud C, Singh S, Feivelson D, Darroch JE. Sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents in developed countries. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(1):24–32. 45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger LH, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Emans SJ, Woods ER, DuRant RH. The association of sexual risk behaviors and problem drug behaviors in high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;20:377–383. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sionean C, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies SL, Hook EW, 3rd, Oh MK. Socioeconomic status and self-reported gonorrhea among African American female adolescents. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(4):236–239. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn S, Bogart LM. Conspiracy beliefs about birth control: Barriers to pregnancy prevention among African Americans of reproductive age. Health, Education, and Behavior. 2005;32:474–487. doi: 10.1177/1090198105276220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Gil AG, Wagner EF, Artigues H. Patterns of sexual risk behaviors and psychiatric disorders in a community sample of young adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(5):473–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1025776102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Windle M, Windle RC. Cumulative sexual intercourse patterns among middle adolescents: Problem behavior precursors and concurrent health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;18:182–191. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00128-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KM, Garnett GP, Ghani AC, Sterne JA, Low N. Investigating ethnic inequalities in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections: Mathematical modeling study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80:379–385. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sex and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck L, Conger R, Kao M. The influence of parental support, depressed affect, and peers on the sexual behaviors of adolescent girls. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14:261–278. [Google Scholar]