Abstract

Restriction-free cloning (RF-cloning) is a PCR-based technology that expands on the QuikChange™ mutagenesis process originally popularized by Stratagene in the mid-1990s, and allows the insertion of essentially any sequence into any plasmid at any location. While RF-cloning is a powerful tool for the design of custom plasmids when restriction sites are not conveniently situated, manually designing the requisite primers can be tedious and error prone. We present here a web-service that automates the primer design process, along with a user interface that includes a number of useful tools for managing both the input sequences and the resulting outputs. RF-Cloning is free and open to all users, and can be accessed at http://www.rf-cloning.org.

INTRODUCTION

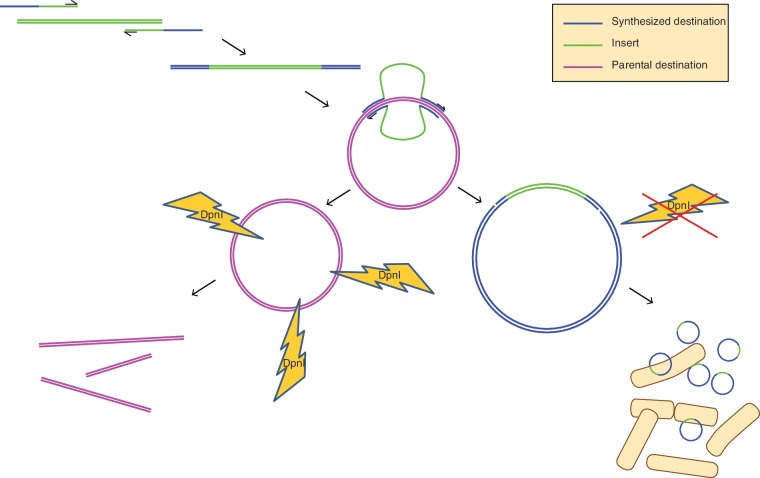

Classical DNA cloning generally involves cleaving a destination plasmid and a target insert sequence with restriction enzymes, and then stitching them together with DNA ligase. This approach is enormously convenient and straight forward when the appropriate restriction sites are well positioned in the sequences being manipulated, but becomes problematic when these restriction sites are not present. A number of ligation-independent cloning technologies have been developed that utilize recombinase enzymes, such as the Gateway® system by Invitrogen and In-Fusion™ by Clontech. Gateway® requires the presence of recombinase-specific attR and attL sequences (1), so there is no gain in overall flexibility. In-Fusion™ allows for recombination to occur at user-specified sites, but the per-reaction cost can be high due to the proprietary recombinase required. PCR-based restriction site-free cloning (RF-cloning) overcomes these limitations, and has been described in the literature numerous times in the past decade (2–6). RF-cloning is based on the overlap extension site-directed mutagenesis technique first described by Steffan Ho in 1989 (7), and commercialized by Stratagene under the name QuikChange™ (8). The technique is initiated by a pair of primers each designed with complementary sequence to both the desired insert and the destination plasmid. High-fidelity PCR is used to first amplify the insert sequence, and then the resulting product is purified for use as a ‘mega-primer' in a secondary PCR reaction, using the destination plasmid as template. During this second reaction, the destination plasmid is amplified in its entirety. PCR customarily results in geometric expansion of product, which can amplify point mutations that occur during synthesis. The mega-primer, on the other hand, only initiates amplification from the parental destination plasmid, resulting in arithmetic accumulation of daughter molecules; this is sufficient for cloning purposes while minimizing mutations. When these newly synthesized strands anneal, the mega-primers act as long complimentary overhangs that circularize the plasmid, forming a nicked hybrid molecule. DpnI is used to degrade the methylated parental plasmid while leaving the unmethlyated in vitro synthesized hybrid plasmids intact and ready to transform competent bacteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of a typical restriction free cloning protocol. Hybrid primers are designed with complementarity to the desired insert (green) and the destination plasmid (blue). A first round of PCR is performed to create a ‘mega-primer’ comprising the insert sequence flanked by sequences complementary to the destination plasmid. During a second round of PCR, the mega-primer initiates replication of the destination plasmid (pink). Since the entire destination plasmid is replicated in the reaction, mega-primer binding to a daughter molecule fails to expose a free 3′-end for polymerase elongation, so accumulation of new product is linear. The destination plasmid must be purified from a DAM+ bacterial stain, since DpnI is used to selectively degrade parental DNA after the second PCR reaction, leaving the unmethylated daughter products intact. The reaction can then be used to transform competent bacteria.

Currently, designing the hybrid RF-cloning primers is a manual task. Four separate primer sequences must be created (two for the insert and two for the plasmid) with compatible melting temperatures (Tm), requiring the investigator to arbitrarily test sequences of varying length until the proper conditions are achieved (2). To automate primer design, we have written an algorithm that accepts a user specified insert sequence, destination plasmid sequence and the desired insert sites as input. The algorithm then returns hybrid primers with the correct orientation and compatible Tm. The service can be accessed through our web based user interface at http://www.rf-cloning.org, or through direct XML requests with the Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP).

PROJECT WORKFLOW

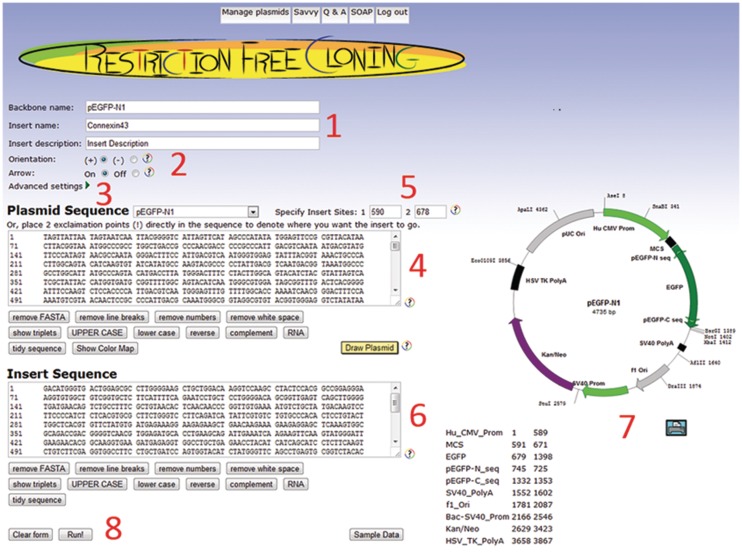

From the RF-Cloning.org home page (Figure 2), the user supplies the sequence of their insert and destination plasmid in plain text or FASTA format. The desired insertion sites in the destination plasmid can be specified numerically, or by placing exclamation marks (!) directly into the plasmid sequence. A list of common plasmids is supplied as a pull-down menu, and the sequence and associated plasmid map are loaded automatically if one is selected. If the user inputs a custom destination plasmid sequence, common features and restriction sites can be automatically identified by clicking the ‘draw plasmid’ button; this will then dynamically generate a plasmid map. The database of common plasmid features has been adapted from the AddGene listing found at http://www.addgene.org/tools/reference/plasmid-features/ (last accessed April 2012), which is an expanded list of the features used by PlasMapper (9). A number of useful sequence manipulation tools (some of which have been adapted from those found at Sequence Massager, http://www.attotron.com/cybertory/analysis/seqMassager.htm) are also included to perform common tasks, such as removal of numbers and whitespace or converting a sequence to its reverse complement. When the user runs the project, they are redirected to the output page, where they will find the newly designed hybrid primers, recommended PCR conditions and new construct sequence (Figure 3). The hybrid primers are necessarily a direct function of the insert sequence and the insertion sites within the destination plasmid, and the design algorithm constrains the final primers to a minimum length and annealing temperature of 18 bases and 55°C on the insert side, and 22 bases and 60°C on the plasmid side. These values are based on general PCR primer design best practices, as well as RF-Cloning specific recommendations (2,10). Annealing temperature is defined by the Wallace–Itakura rule for sequences <14 bases long (°C = 4[G + C] + 2[A + T]), while nearest-neighbor thermodynamics are used for sequences 14 bases long or greater (11,12). The nearest neighbor calculations assume a primer concentration of 500 nM, monovalent cation concentration of 50 mM and divalent cation concentration of 0 mM. Of course, magnesium has a stabilizing effect on DNA hybridization (12) and is also a necessary component of the PCR reaction buffer, so the calculated annealing temperature is 5–10°C below the actual primer Tm expected in the final PCR reaction. The default minimums for length and annealing temperature can be over-ridden by the user from the main page using the ‘advanced settings’ form.

Figure 2.

RF-Cloning.org input page. (1) Optional information about the project. (2) ‘Orientation’ refers to complementarity of the insert sequence relative to the destination plasmid, and ‘arrow’ refers to how the insert will be drawn in the Savvy map. (3) Collapsible form fields where the default primer length and annealing temperature parameters can be modified. (4) Destination plasmid sequence can be entered manually (numbers and FASTA comments are ignored) or by selecting popular plasmids from the dropdown menu. (5) Insert sites within the plasmid sequence should be designated numerically in the fields provided (the very front of the plasmid is position 0), or by placing exclamation points (!) directly into the sequence. (6) Insert sequences must be entered manually (numbers and FASTA comments are ignored). (7) Plasmid maps are dynamically generated based on destination plasmid sequence. (8) When ready, the project can be submitted to the server.

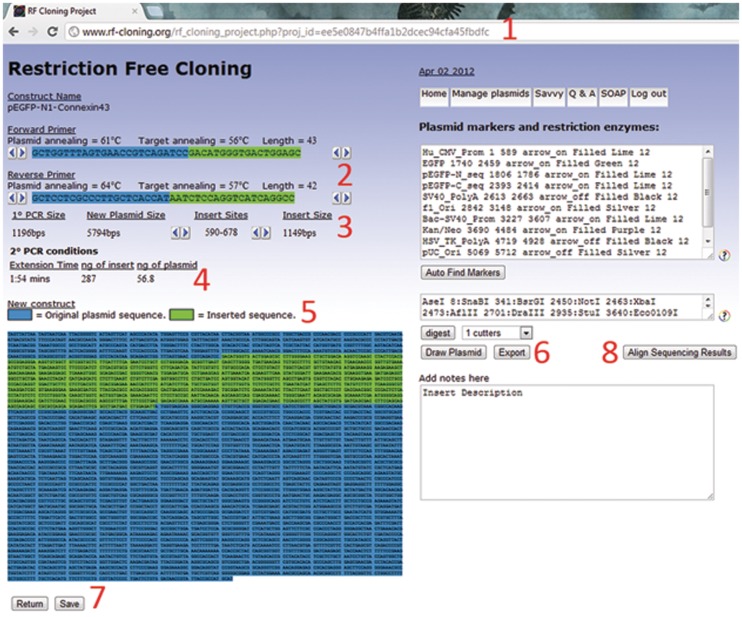

Figure 3.

RF-Cloning.org output page. (1) A unique 32 byte hash code is generated for all new projects, and is present in the URL for bookmarking purposes. (2) The hybrid primers are color coded, blue for sequence complementary to the plasmid, and green for the insert. The length of the primers can be adjusted by clicking on the arrow buttons if the user wishes to alter the annealing temperature. (3) If the insert site needs to be adjusted, the user can use the provided arrow buttons. (4) The secondary PCR conditions are optimized for iProof or Phusion as the polymerase, so the user should follow manufacturer’s instructions if using another high fidelity enzyme. ‘Insert’ refers to the mega-primer purified from the primary PCR reaction. (5) The entire sequence of the new plasmid is output, with insert in green and parental plasmid in blue. (6) The plasmid map can be drawn by specifying the positions of markers manually, or by auto-finding common features. Restriction enzyme cut sites can also be specified or automatically identified. If desired, the plasmid can be exported as a genbank file. (7) All projects are automatically saved, but making changes to the output page will activate the save button so those changes can be uploaded to the database. If the user has registered an account to access the plasmid management system, the save button will attach the project to their profile. (8) After the project has been completed and sent for sequencing, the sequencing results can be copied into a popup window for BLAST2 sequence alignment.

All new projects are assigned a unique 32 byte hash code and are immediately saved to the database at runtime. The hash code is appended to the output page URL, so the user is able to bookmark their projects should they wish. The length of the hybrid primers and insertion sites can be manually adjusted on the output page by clicking the associated arrow buttons, and a save button is provided to update the project in the database if any changes are made. If users would prefer to not keep track of their project hash keys manually, they are able to register a free account to access a simple project/plasmid management system where they can save their work.

Throughout the site, users are able to graphically visualize plasmids using an integrated version of ‘Savvy’. Savvy is a scalable vector graphics (SVG) plasmid map drawing software adapted from the original version 0.1 source code kindly provided by Dr Malay Basu (http://www.bioinformatics.org/savvy/). These plasmid maps are generated dynamically, and if the user wishes to retain a copy for their own records, the SVG file can be downloaded by clicking the associated ‘print’ symbol in the lower right hand corner of the image. The SVG format can be opened by vector graphics manipulation software from various commercial vendors (e.g. Adobe Illustrator and CorelDRAW) as well as the open source SVG editor, Inkscape (http://inkscape.org/). Plasmids can also be exported in genebank format, which is importable by most plasmid management platforms.

RECOMMENDED RF-CLONING PROTOCOL

By default, the starting hybrid primers will be at least 40 bp long with an annealing temperature of at least 55°C for the primary PCR (amplification of insert) and at least 60°C for the secondary PCR (extension around the plasmid). High-fidelity DNA polymerase should be used for all PCR reactions, and it has been our experience that iProof (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and Phusion (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) produce consistent results. To generate the mega-primer, use a standard 50 μl PCR reaction (1× PCR buffer, 200 μM dNTP, 500 nM of each primer, 1 U polymerase, user defined amount of starting template) and cycle 30–35 times with the RF-Cloning.org recommended annealing temperature, followed by product purification (e.g. by gel extraction). A recent study has identified the optimal conditions for the secondary PCR reaction (2): a molar insert:plasmid ratio of ≥20, using 20–50 ng of parental plasmid as starting material, 18–20 amplification cycles (note that cycling more than 20 times has significant detrimental effects) and setting the annealing temperature to 5–10°C below Tm. A 20 μl reaction is sufficient for the secondary PCR, and upon completion it should be treated with 20 U of DpnI for 2 h at 37°C (DpnI is active in the iProof and Phusion PCR buffers), followed by a 20 min inactivation at 80°C. RF-cloning reactions are inherently low efficiency, so using super-competent bacteria (>108 CFU/μg pUC18) for the subsequent transformation can be beneficial, although we usually find sub-cloning grade competent cells (106 CFU/μg pUC18) to be sufficient. The design algorithm at RF-Cloning.org can also be used to create hybrid primers compatible with other overlap-extension based methods, such as fusion PCR (13) or the recently described transfer-PCR (14), although the parameters associated with the downstream protocol will need to be optimized by the user.

IMPLEMENTATION

RF-Cloning.org runs on a standard LAMP configuration (Debian 6.0 ‘Squeeze’ web server, Apache2, MySQL and PHP), and the user interface has been successfully tested on Firefox 3+, Opera 9+, Safari 3+, Internet Explorer 9+ and Chrome web browsers, on Windows XP/Vista/7, Debian based distributions of Linux and Mac OS-X. All critical functionality of the site is also present when using Internet Explorer 7 and 8, but due to incomplete support of the SVG web standard by these older browsers, they are unable to download the Savvy plasmid maps. Many features of RF-Cloning.org communicate with the web server via asynchronous JavaScript calls, so JavaScript support must be enabled at all times. Common gateway interface scripts are implemented in PHP, Perl [using pre-existing BioPerl modules (15)], and C++ [select components of the BLAST+ suite, version 2.2.24, NCBI C++ toolkit (16)]. For those wishing to access the RF-Cloning design algorithm directly from custom scripts, we have included a SOAP server to accept incoming XML requests (http://www.rf-cloning.org/classes/rf_cloning_server.php). The affiliated WSDL file and sample SOAP clients can be downloaded from http://www.rf-cloning.org/soap_server.php.

CONCLUSION

RF-cloning is a powerful technique for constructing custom plasmids, but designing the necessary hybrid primers has been a manual task up until now. We have created RF-Cloning.org to help automate hybrid primer design, which is both faster and reduces the likelihood of human error. An emphasis has been placed on creating an intuitive browser-based user interface, although the underlying design algorithms can be accessed by direct XML requests if a user wishes to create their own custom batch scripts.

FUNDING

The Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Research Trainee Award to S.R.B.); Canadian Institute of Health Research (Operating grant to C.C.N.). Funding for open access charge: Canadian Institute of Health Research.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Dr Kurt Hass and Dr Douglas Allan for critical review of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA. DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination. Genome Res. 2000;10:1788–1795. doi: 10.1101/gr.143000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques. 2010;48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen GJ, Qiu N, Karrer C, Caspers P, Page MG. Restriction site-free insertion of PCR products directionally into vectors. Biotechniques. 2000;28:498–500, 504–505. doi: 10.2144/00283st08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiser M, Cebe R, Drewello D, Schmitz R. Integration of PCR fragments at any specific site within cloning vectors without the use of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase. Biotechniques. 2001;31:88–90, 92. doi: 10.2144/01311st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unger T, Jacobovitch Y, Dantes A, Bernheim R, Peleg Y. Applications of the Restriction Free (RF) cloning procedure for molecular manipulations and protein expression. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;172:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Ent F, Lowe J. RF cloning: a restriction-free method for inserting target genes into plasmids. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2006;67:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papworth C, Bauer JC, Braman J. QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis. Strategies. 1996;9:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong X, Stothard P, Forsythe IJ, Wishart DS. PlasMapper: a web server for drawing and auto-annotating plasmid maps. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W660–W664. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieffenbach CW, Lowe TM, Dveksler GS. General concepts for PCR primer design. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3:S30–S37. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.3.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SantaLucia J., Jr A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1460–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Ahsen N, Oellerich M, Armstrong VW, Schutz E. Application of a thermodynamic nearest-neighbor model to estimate nucleic acid stability and optimize probe design: prediction of melting points of multiple mutations of apolipoprotein B-3500 and factor V with a hybridization probe genotyping assay on the LightCycler. Clin. Chem. 1999;45:2094–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erijman A, Dantes A, Bernheim R, Shifman JM, Peleg Y. Transfer-PCR (TPCR): a highway for DNA cloning and protein engineering. J. Struct. Biol. 2011;175:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stajich JE. An Introduction to BioPerl. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;406:535–548. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-535-0_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]