Abstract

Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) are very important to the biotech industry, particularly the emerging biofuel industry because CAZymes are responsible for the synthesis, degradation and modification of all the carbohydrates on Earth. We have developed a web resource, dbCAN (http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/annotate.php), to provide a capability for automated CAZyme signature domain-based annotation for any given protein data set (e.g. proteins from a newly sequenced genome) submitted to our server. To accomplish this, we have explicitly defined a signature domain for every CAZyme family, derived based on the CDD (conserved domain database) search and literature curation. We have also constructed a hidden Markov model to represent the signature domain of each CAZyme family. These CAZyme family-specific HMMs are our key contribution and the foundation for the automated CAZyme annotation.

INTRODUCTION

Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZyme), responsible for the synthesis, degradation and modification of all the carbohydrates on Earth, are an important class of proteins, particularly for the biotech industry, such as the biofuel industry. The CAZy database (short as CAZyDB hereafter) represents the currently most comprehensive database (http://www.cazy.org) for CAZyme proteins, which consists of 308 CAZyme families as of April 2011 (excluding nine deprecated ones and five unclassified families, e.g. GT0), grouped into five functional classes: glycoside hydrolases (GHs), glycosyltransferases (GTs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs) and the non-catalytic carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs). CAZyDB is updated every few weeks, mainly to add new families to keep up with the most recent literature. The popularity of the database along with its classification scheme is obvious based on its high citation number (1).

While popular, we see three issues with CAZyDB based on our own experience in using it. First, CAZyDB maintains a list of proteins from GenBank and UniProt belonging to each CAZyme family but does not provide an easy way to query, search or download the sequence, structure and annotation data. Second, the database does not explicitly define the ‘signature domain’ for any of the CAZyme families; so from a user’s perspective, it is unknown what the defining (signature) domain is for each family and where the domain is located in a full-length protein. Last and most importantly, CAZyDB does not provide a way for an automated annotation of the CAZyme members in a given genome, which becomes increasingly needed with more and more genomes and metagenomes being sequenced at an increasing rate.

A common practice now when trying to annotate a genome is to BLAST the genome against the annotated full-length CAZyme proteins in CAZyDB (2–4). Often this does not work well for annotating CAZymes, many of which are multiple-domain proteins, e.g. searching for short CBM regions in GHs. Another approach is to use Pfam models that are associated with CAZyme families for domain-based annotation (4–7). The CAZyme Annotation Toolbox (CAT) (6) falls into this category, which was recently developed to address the automated annotation issue. It combines a BLAST search and a Pfam domain-based search; to extend the Pfam search result, an association rule learning algorithm was used to find the correspondence between Pfam domains and CAZyme families. The main problems with the CAT program include: (i) it did not define a signature domain for each CAZyme, the key information needed for accurate and reliable annotation of CAZyme proteins in an automated fashion and (ii) its Pfam domain-based search covers only 46% (142/308) of the CAZyme families.

For a comprehensive and accurate annotation of the CAZyme families, users often have to contact the developers of CAZyDB for their semi-automatic annotations (1,8–10). This is clearly becoming a bottleneck and is not consistent with the way the other popular protein domain/family databases such Pfam (11), InterPro (12) and CDD (13) handle the annotation needs, which all provide data and automated services through their websites. Clearly, there is an urgent need for an accurate and reliable tool for automated and comprehensive annotation of CAZyme proteins.

To fully address the issues outlined above, we developed a web resource, dbCAN (http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/), based on the classification scheme of CAZyDB. We aimed to provide a solution for automated CAZyme annotation for any given genome, as well as an easy and convenient access to sequences, domain models, alignments and phylogeny data of CAZyme-related enzyme families and functional modules, hence addressing all the three issues discussed above. The basis for dbCAN’s automated and comprehensive annotation is the clearly defined signature domain models of all the 308 CAZyme families, which are not provided by any existing tools, including CAZyDB and CAT. In addition to the current five CAZyme classes, we also included in dbCAN three additional domain modules: dockerin, cohesin and SLH (S-layer homology domain), which are critical for forming cellulosomes, a multi-protein complex that can efficiently degradate carbohydrate-rich biomasses (14).

IDENTIFICATION AND DEFINITION OF SIGNATURE DOMAINS

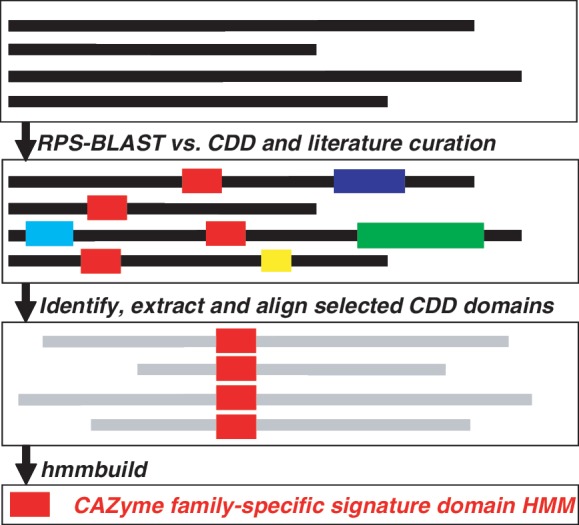

In order to define a signature domain for each CAZyme family, we have identified an annotated functional domain by referring to the CDD (Conserved Domain Database) (13) search result and the published literature (Figure 1) of the member GenBank proteins in that family. Specifically, we analyzed the CDD search results (by RPS-BLAST) of the member proteins to select a CDD model that matches most of these proteins with significant sequence similarities. The underlying assumption is that proteins of the same CAZyme family must share a common region, which might be represented by some annotated functional domain in the public protein domain databases. Moreover, we manually reviewed the functional description of the top CDD models to ensure that the selected model indeed represents the similar functional activities of the CAZyme family. For instance, family CE2 was assigned the CDD domain cd01831 (Endoglucanase_E_like) as this domain covers all GenBank proteins in this family with very significant E-values. It is worth noting that there are redundant CDD models as cd01831, e.g. pfam00657 (Lipase_GDSL), cd00229 (SGNH_hydrolase) and COG2755 (TesA, Lysophospholipase L1 and related esterases). Although these models describe different biochemical activities, they all match significantly overlapped regions in the member proteins of CAZyme family CE2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of our procedure for identifying and defining signature domain models for an example CAZyme family. Here this family contains four full-length proteins with different lengths. The red box is the signature domain regions defining the CAZyme family. It could be either identified by searching against annotated functional domain models in the CDD database or retrieved from literature curation. Boxes in other colors are non-overlapped domain regions annotated by other CDD models. The CDD search is done by RPS-BLAST, the multiple sequence alignment is done by MAFFT (default parameters), the building of HMM is done by hmmbuild and all other processes are done by self-developed perl scripts.

We were able to find a CDD model (defined as a position-specific scoring matrix) for 248 CAZyme families out of the total of 308 (Supplementary Data S1). Since CDD is a general protein domain database containing over 40 000 models defined based on the alignment of some seed proteins, the selected CDD models are not exactly CAZyme family specific. In addition, analyses of these CDD models indicate multiple CAZyme families may share the same CDD model. To build CAZyme family-specific models, we first identified the domain regions in the component GenBank proteins of each CAZyme family based on its selected CDD model using hmmsearch (a command in the HMMER 3.0 package, hmmer.org) and then generated a hidden Markov model (HMM, by hmmbuild, hmmer.org) based on the multiple sequence alignment [by MAFFT v6.603b (15)] of the identified CDD domain regions, which gives rise to a unique HMM for each of the 248 families.

The other 60 CAZyme families did not have a CDD model since no model covers the majority (80%) of the component GenBank proteins for each of these families (Supplementary Data S1). For 20 of them (including 15 CBM families, Supplementary Data S2), we were able to identify an initial signature domain for some characterized GenBank proteins in each family through manual curation of the published literature; we then populated the domain regions by retrieving them (by BLASTP) from all component proteins of the family and finally we were able to build an HMM specifically for the family using the aforementioned procedure (i.e. MAFFT + HMMER). For the remaining 40 families (mostly small and non-CBM families), CDD and literature search did not provide any signature domain information. For each such family, we generated a multiple sequence alignment (by MAFFT) among all component full-length GenBank proteins and then manually edited the alignment by removing long gaps and ambiguously aligned regions. Based on these carefully edited alignments, we then built an HMM (hmmbuild) for each of these families to represent its signature domain.

Overall we were able to generate a unique and family-specific signature HMM for each of the 308 CAZyme families. Using these HMMs to search against the CAZyme component (GenBank) proteins, we were able to correctly identify at least 95% of the component proteins from each of the 308 CAZyme families (Supplementary Data S1).

EVALUATION OF ANNOTATION ACCURACY

With the signature domain HMMs available, we are now able to perform hmmscan of any given protein data set against the 308 dbCAN HMMs for an automated CAZyme annotation.

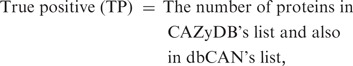

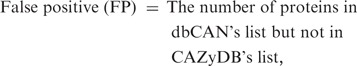

To evaluate the quality of the automated annotation, we compared our annotation results with the CAZyme protein list annotated in CAZyDB done by semi-automatic annotation (1), on one bacterial genome (annotated protein data set in the genome) Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 and one plant genome Arabidopsis thaliana. When processing the hmmscan result, we noticed that there are three parameters that can impact the annotation result: (i) E-value; (ii) alignment length; and (iii) alignment coverage (w.r.t CAZyme HMM). Since shorter alignments tend to have less significant E-values compared to the longer ones, we used E-value < 1e − 3 as the cutoff for alignments shorter than 80 amino acids, while used E-value < 1e − 5 for alignments longer than 80 amino acids. This cutoff setting allows short but significant CBM matches to be kept. The third parameter, alignment coverage measuring the fraction of CAZyme HMM covered by the alignment, is also important: if a protein sequence matches a CAZyme HMM with a significant E-value while the alignment covers only a small fraction of the HMM, the protein is either a truncated fragment (e.g. un-functional) or a false match. To remove such proteins, we tried different cutoffs on the alignment coverage and found that it can significantly affect the sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV, also called precision) of the dbCAN annotation (Supplementary Data S9), where

|

|

|

Basically we regarded all CAZyme proteins of the two genomes annotated by CAZyDB as true positives. Assuming the annotated CAZyme protein list by CAZyDB are accurate and complete, we found that our automated annotation has the best overall performance for C. thermocellum (sensitivity = 99.3% and PPV = 89.4%) using alignment coverage >0.5 as the threshold, while for A. thaliana (sensitivity = 96.3% and PPV = 78.8%) using alignment coverage >0.3 as the threshold (Supplementary Data S9).

We also performed a similar assessment using a set of rebuilt HMMs without including any information from the two genomes C. thermocellum and A. thaliana that we were testing against. Specifically, we removed all the proteins of the two genomes from the list of all 308 CAZyme families and rebuilt the HMMs based on this reduced protein list. The performance of the new HMMs is as follows: sensitivity = 98.6% and PPV = 86.1% for C. thermocellum and sensitivity = 95.6% and PPV = 76.6% for A. thaliana (Supplementary Data S10). While the performance dropped slightly, the results indicate the robustness of dbCAN’s HMMs for CAZyme annotation.

The detailed comparison results in terms of the TP, TN and FP values for the two genomes are summarized in Supplementary Data S3–S8. Obviously, we did well in identifying most CAZymes from the two organisms, but in the meantime included many FP proteins. However, another possibility is that these ‘FP’ proteins may be real CAZyme proteins but missed by the CAZyDB, since we noticed that many of the FP proteins have very significant E-values against the CAZyme family HMMs. For example, Cthe_1186 of C. thermocellum was found to match CE10 family HMM with an E-value = 1.20e − 64 and AT1G29660.1 of A. thaliana matched CE16 HMM with an E-value = 1.6e − 28 (see Supplementary Data S11 for the alignment). The real truth can only be found out through experimental studies on these proteins.

COMPARISON WITH BLAST-BASED AND CDD-BASED SEARCH STRATEGIES

We also compared our HMM-based annotation with the other two often used annotation strategies. The first is using BLASTP to search the proteins of C. thermocellum and A. thaliana against the CAZyDB (after excluding the proteins of the two genomes). Similar to domain-based hmmscan search, we also processed BLAST search results by considering two parameters: E-value and bit-score. Specifically, we used the same E-value cutoffs as above and then tried different bit-score cutoffs to parse the BLAST outputs. Supplementary Data S12 shows that for C. thermocellum using bit-score >425 as cutoff gave the most balanced performance (sensitivity = 92.4%, PPV = 96.4% and average of the two = 94.4%) and that for A. thaliana using bit-score >350 as cutoff gave the most balanced performance (sensitivity = 78.8%, PPV = 66.7% and average = 72.7%). These numbers appear to be similar to those of dbCAN’s performance for C. thermocellum (sensitivity = 99.3%, PPV = 89.4% and average = 94.3%) while they are much worse than those of dbCAN’s for A. thaliana (sensitivity = 96.3%, PPV = 78.8% and average = 87.6%).

More importantly, a key drawback with BLAST-based strategy is that it can only tell if the query protein has a very significant hit in CAZyDB and then transfer the CAZyme family assignment from the hit to the query protein. Supposing the query protein has a GH and a CBM domain in reality, while the hit has only a GH domain, the BLAST annotation will only assign the query to the GH family while miss the CBM family assignment. We can imagine even more complex situations with multiple such domains. In contrast, dbCAN annotation provides much richer information such as which and how many CAZyme domains (including, e.g. repetitive CBM domains) a query protein has and where the boundaries of these domains are in the full-length protein. Therefore, overall dbCAN offers much better and more comprehensive CAZyme annotation than the simple BLAST search.

For the 248 CAZyme families having a selected CDD domain model, we checked if the CDD models can lead to accurate CAZyme annotation. We found that the CDD-based search was able to identify 94.3% (C. thermocellum) and 87.1% (A. thaliana) CAZyme homologs that are identified by our HMMs. However, one major issue with the CDD-based search is that CDD models are not specifically built for CAZyme families. There are cases of multiple CAZyme families mapped to the same CDD model, e.g. GT2, GT12 and GT45 families all pointing to pfam00535; hence one cannot tell which specific CAZyme family a query protein belongs to if it matches the CDD model pfam00535. Furthermore, 60 CAZyme families do not have a CDD model so the CDD-based CAZyme annotation is incomplete.

Overall our CAZyme family-specific HMMs-based method provides a significantly better solution to the automated CAZyme annotation problem than these simpler strategies.

DESCRIPTION OF THE dbCAN ANNOTATION SERVER

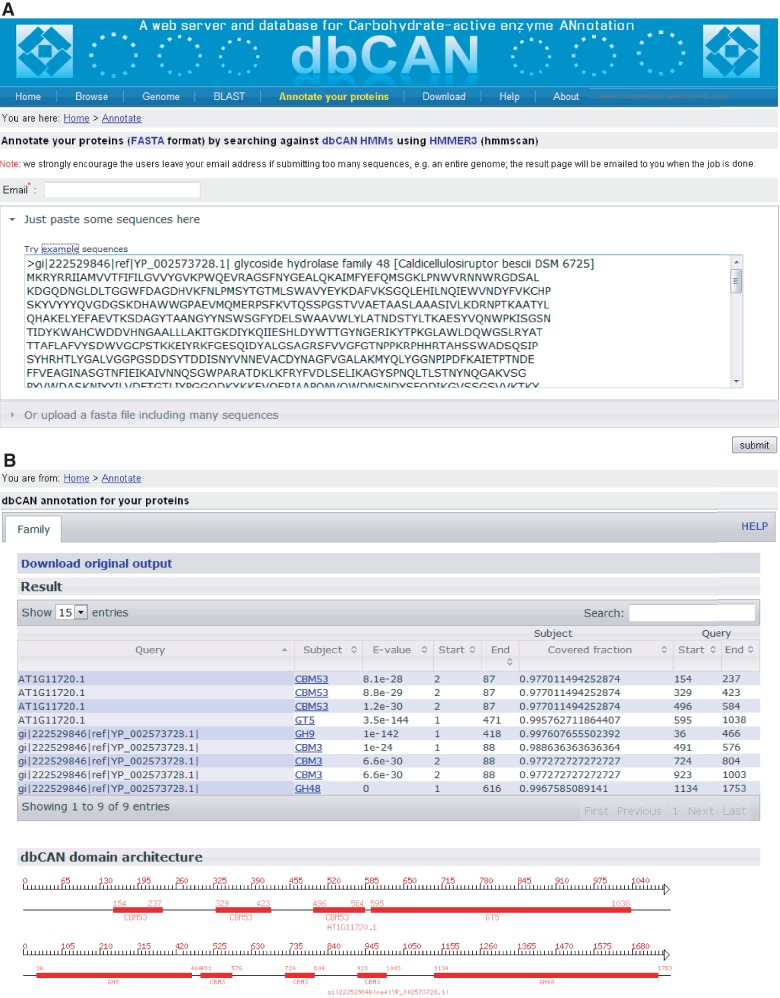

dbCAN provides a capability for automated CAZyme annotation for any given genome or set of protein sequences. Like most of the public protein databases such as Pfam and CDD, we make all the HMMs available through our website. Users can download the HMMs and run hmmscan on their interested proteins/genomes against these domain models. We have built a web server (Figure 2A) so that users can upload their protein or genome sequences for CAZyme annotation. A submitted job is processed on a Linux cluster with 100 computing nodes. For small bacterial genomes such as C. thermocellum, it normally takes <10 min to finish the annotation. A result page (Figure 2B) will be returned showing the detailed information of the locations of the identified CAZyme domains and a diagram of the domain architecture, which is very useful for viewing multi-domain proteins.

Figure 2.

Snapshots of dbCAN annotation server. (A) The query page, where users can paste some FASTA format protein sequences in the text box or upload a text file containing the FASTA sequences. Clicking on ‘submit’ will invoke the hmmscan program in the backend server to search the queried sequences against the dbCAN HMMs. (B) The result page, where users can download the raw output from the hmmscan run and view the processed tabular format output (if alignment length >80 amino acids, use E-value < 1e − 5, otherwise use E-value < 1e − 3). A diagram is shown in the bottom to illustrate the CAZyme domain architecture according to the positional information in the tabular output.

In addition, dbCAN provides pre-computed sequence alignments, HMMs and phylogenies of the signature domains in each and every CAZyme family, downloadable from the dbCAN website and it also provides the following capabilities: CAZyme family-based browsing, genome-based browsing, keyword search, BLAST search as well as detailed functional annotation for every sequence included in dbCAN.

APPLICATION TO METAGENOME DATA SETS

Metagenomes, mixture of genomic DNAs from uncultured environmental microorganisms (16), represent a new source of enormously large gene pools containing potentially many new catalytic enzymes that could be of use for biotechnology (17–19). We have applied the 308 HMMs to search against a number of metagenomes such as the JGI metagenomes (20), the CAMERA marine metagenomes (21–23) and two recently published animal gut metagenomes (5,24). Using E-value < 1e − 5 as the cutoff, we obtained over one million (1 038 912) full-length CAZyme homologous proteins containing 1 209 177 CAZyme domain regions, all of which are accessible from the dbCAN website. This is about three times of the number of CAZyme homologs (358 959) in the NCBI-nr database, indicating that there are many new CAZyme related proteins in the environmental metagenomes awaiting further investigation (manuscript in preparation); many of them may represent new catalytic enzymes that could be of good use for the biotech industry (17,25).

DISCUSSION

dbCAN is designed to offer a free, easy-to-use and public service of automated CAZyme annotation to users worldwide. Such a service will be highly useful to researchers who sequenced biotech-related genomes and metagenomes and will be very valuable in helping to find novel catalysts, e.g. (2–4,6–10). A key unique feature of the dbCAN database is its collection of the CAZyme family-specific HMMs, which are built based on the annotated CAZyme proteins by CAZyDB. The following is worth noting about using dbCAN.

dbCAN models are different from the selected CDD models, for we just used CDDs to locate the CAZyme signature domain regions and build our own models based on the domain regions in the annotated CAZyme proteins. Therefore, dbCAN models are CAZyme-specific and each CAZyme family has a unique HMM. In addition, 60 dbCAN models are new and have not been described in CDD.

dbCAN is built upon CAZyDB but not meant to be a substitute of CAZyDB. dbCAN aimed to enable automated CAZyme annotation at a genome scale, while CAZyDB is the original database that created all the CAZyme families since early 1990s and will continue to create new families. The creation of the new families is often done by the coordination between experimentalists and the CAZyDB team. We will add new dbCAN HMMs as soon as CAZyDB adds new CAZyme families, to provide a service complementary to that by CAZyDB.

CAZyDB may have the domain models internally for many if not all CAZyme families, but do not release them to the public. This might be because these models are constantly updated or are considered to be not good for the use of automated annotation. In fact, CAZyDB performs the semi-automatic annotation for newly sequenced genomes. However, this led to the reality that the entire annotation process is invisible to the users, i.e. without providing any guidance to the users about how they can do automated CAZy annotation when they desire so.

dbCAN annotation explicitly offers the positions of each CAZyme domain in each full-length protein, which are missing for all annotated proteins in CAZyDB. However, it should be noted that the exact domain boundaries in each protein annotated by dbCAN might be slightly different from those in CAZyDB.

CONCLUSION

In summary, through dbCAN, we have made two key contributions: (i) we recovered and defined a signature domain model for each and every CAZyme family and (ii) we release all models freely to the community and build a web server to facilitate efficient annotation of CAZyme proteins at a genome scale. With dbCAN models and the web server, users can easily obtain a comprehensive and automated CAZyme annotation, on which they can perform their own manual curation if they choose to do so.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Data 1–12.

FUNDING

U.S. Department of Energy [DE-PS02-06ER64304]; National Science Foundation [DEB-0830024]; Office of Biological and Environmental Research in the DOE Office of Science [to The BioEnergy Science Center]. Funding for open access charge: The BioEnergy Science Center.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the Research Computing Center of the University of Georgia for providing computing facility. We thank Wen-Chi Chou for helping with the curation of CAZyme signature domains in the early stage of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D233–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li LL, McCorkle SR, Monchy S, Taghavi S, van der Lelie D. Bioprospecting metagenomes: glycosyl hydrolases for converting biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2009;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasse L, Bercovici J, Pizzut-Serin S, Robe P, Tap J, Klopp C, Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Leclerc M, et al. Functional metagenomics to mine the human gut microbiome for dietary fiber catabolic enzymes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1605–1612. doi: 10.1101/gr.108332.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allgaier M, Reddy A, Park JI, Ivanova N, D’Haeseleer P, Lowry S, Sapra R, Hazen TC, Simmons BA, VanderGheynst JS, et al. Targeted discovery of glycoside hydrolases from a switchgrass-adapted compost community. PloS One. 2010;5:e8812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess M, Sczyrba A, Egan R, Kim TW, Chokhawala H, Schroth G, Luo S, Clark DS, Chen F, Zhang T, et al. Metagenomic discovery of biomass-degrading genes and genomes from cow rumen. Science. 2011;331:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1200387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park BH, Karpinets TV, Syed MH, Leuze MR, Uberbacher EC. CAZymes Analysis Toolkit (CAT): web service for searching and analyzing carbohydrate-active enzymes in a newly sequenced organism using CAZy database. Glycobiology. 2010;20:1574–1584. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu L, Wu Q, Dai J, Zhang S, Wei F. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17714–17719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017956108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muegge BD, Kuczynski J, Knights D, Clemente JC, Gonzalez A, Fontana L, Henrissat B, Knight R, Gordon JI. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science. 2011;332:970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1198719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duplessis S, Cuomo CA, Lin YC, Aerts A, Tisserant E, Veneault-Fourrey C, Joly DL, Hacquard S, Amselem J, Cantarel BL, et al. Obligate biotrophy features unraveled by the genomic analysis of rust fungi. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9166–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019315108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brulc JM, Antonopoulos DA, Miller ME, Wilson MK, Yannarell AC, Dinsdale EA, Edwards RE, Frank ED, Emerson JB, Wacklin P, et al. Gene-centric metagenomics of the fiber-adherent bovine rumen microbiome reveals forage specific glycoside hydrolases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1948–1953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806191105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, et al. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D205–D210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayer EA, Lamed R, White BA, Flint HJ. From cellulosomes to cellulosomics. Chem. Rec. 2008;8:364–377. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handelsman J. Metagenomics: application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:669–685. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.669-685.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Arrojo L, Guazzaroni ME, Lopez-Cortes N, Beloqui A, Ferrer M. Metagenomic era for biocatalyst identification. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010;21:725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HS, Kwon KK, Kang SG, Cha SS, Kim SJ, Lee JH. Approaches for novel enzyme discovery from marine environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010;21:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godzik A. Metagenomics and the protein universe. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markowitz VM, Chen IM, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, Ratner A, Anderson I, Lykidis A, Mavromatis K, et al. The integrated microbial genomes system: an expanding comparative analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D382–D390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yooseph S, Sutton G, Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Williamson SJ, Remington K, Eisen JA, Heidelberg KB, Manning G, Li W, et al. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: expanding the universe of protein families. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seshadri R, Kravitz SA, Smarr L, Gilna P, Frazier M. CAMERA: a community resource for metagenomics. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, Halpern AL, Rusch D, Eisen JA, Wu D, Paulsen I, Nelson KE, Nelson W, et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science. 2004;304:66–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy J, Marchesi JR, Dobson AD. Marine metagenomics: strategies for the discovery of novel enzymes with biotechnological applications from marine environments. Microb. Cell Fact. 2008;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]