Abstract

Barrett esophageal cancer has the fastest growing incidence of any cancer in Western countries. In Asian countries, most cases of esophageal cancer consist of squamous cell carcinomas, not adenocarcinomas. Recently, however, the increase in the number of Barrett esophagus cases with subsequent Barrett cancer has become worrisome in Asian countries, as the number of patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease has been increasing in these countries. In this review, recent reports regarding Barrett esophagus in Asian countries have been collected and this problem is discussed from various perspectives. In Asia, long-segment Barrett esophagus is much less prevalent than in Western countries, whereas short-segment Barrett esophagus is frequently found. In epidemiologic studies, evaluation of the prevalence of Barrett esophagus is limited by poor interob-server diagnostic agreement. Standard criteria for the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus in Asian patients, especially of the short-segment type, should be established as soon as possible. A high prevalence of hiatal hernia and a decreasing prevalence of Helico-bacter pylori infection may increase the number of Barrett esophagus cases and subsequent Barrett cancer in Asian countries in the near future. Therefore, a strategy for the clinical management of Barrett esophagus in Asian countries should be devised.

Keywords: Barrett esophagus, Asian population, endoscopic diagnosis, Helicobacter pylori infection

Barrett esophagus is defined as intestinal metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa, leading to replacement of the esophageal squamous epithelium with columnar epithelium.1,2 Esopha-geal adenocarcinoma, namely Barrett cancer, derived from Barrett esophagus has been rapidly increasing during the last two decades in North America, Australia, and Europe. Approximately 60% of Caucasian patients with esophageal cancer living in the United States have adenocarcinoma in Barrett esophagus.3 Columnar-lined esophagus with intestinal metaplasia expressing MUC2 core protein can develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma.4–7 Therefore, in Western countries, it is quite reasonable to define columnar-lined esophagus with goblet cell metaplasia as Barrett esophagus with malignant potential, as goblet cells express MUC2 core protein. In Asian countries, the majority of esophageal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. The number of patients with Barrett cancer is small, and only approximately 1% of cases with esophageal cancer are histo-logically adenocarcinomas.8 One reason for the low prevalence of Barrett cancer in Asia may be that Barrett esophagus cases are mainly short-segment (<3 cm). However, as with long-segment Barrett esophagus (LSBE; >3 cm), some short-segment Barrett esophagus (SSBE) cases also show malignant potential.9–11 Reports of a gradually increasing incidence of Barrett cancer in Asia suggest that particular attention should be paid to these patients.12,13 Accordingly, the strategy for clinical management of Barrett esophagus in Asia, as well as in Western countries, should be established. This review article evaluates the present status of Barrett esophagus in Asia and discusses perspectives on its diagnosis and treatment.

Prevalence of Barrett Esophagus in Asia

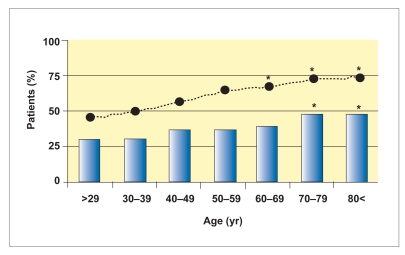

According to recent reports from Western countries, the prevalence of Barrett esophagus (histologically confirmed by the presence of goblet cell metaplasia/specialized columnar epithelium), LSBE, and SSBE is 1.6–25.0%, 0.5–7.2%, and 1.1–17.2%, respectively.14–19 In these reports, most of the patients were Caucasian. In patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the prevalence of Barrett esophagus is over 10%.20,21 Cameron and associates reported that LSBE showed a fairly rapid evolution to its full length with little subsequent change. They observed no age-related increase in the prevalence of LSBE.22 On the other hand, in our study, we found that change in the prevalence of Barrett esophagus (which was 99% SSBE) was age-related, as shown in Figure 1. In our study, Barrett esophagus was significantly more prevalent in patients over 70 years of age than in younger patients. This finding suggests that the pathophysiology of Barrett esophagus (mainly SSBE) may be different in Asia than in the West (which has a high LSBE prevalence).

Figure 1.

The prevalence of patients with Barrett esophagus (indicated by the bars) and hiatal hernia (indicated by the black dots) correlates with increasing age. During the study period of 2004– 2006, 333 patients with histologically confirmed Barrett esophagus were found in 1,997 patients who underwent eso-phagogastroduodenoscopy. In patients over 70 years of age, the prevalence of Barrett esophagus and hiatal hernia was higher than that in the younger population.

*P<.05, compared to the patients younger than 40 years of age.

Reports examining the prevalence of Barrett esophagus in Asian countries are shown in Table 1.7,8,12,23–39 LSBE prevalence in Asia is extremely low (<1.0% of all Barrett esophagus patients in most reports). In contrast, SSBE prevalence in Asia is greater than 96% of all Barrett esophagus patients. The prevalence data vary, as demonstrated in Table 1, possibly due to racial differences in Asian countries23 or differences in how the Barrett esophagus was diagnosed (endoscopically vs histologically). The prevalence of endoscopic versus histologic Barrett esophagus also varied widely. Armstrong was the first researcher to recommend that “endoscopic Barrett esophagus” be considered synonymous with esophageal columnar-appearing mucosa or columnar-lined esophagus.40 The most important reason for the differentiation is the difficulty in diagnosing Barrett esophagus endoscopically. In particular, the endoscopic diagnosis of SSBE is less reliable than that of LSBE.41,42

Table 1.

Prevalence of Barrett Esophagus in Asian Countries

| Study | Study Period | Country or Ethnicity | Sample Size (N) | Study Method | Prevalence of Barrett Esophagus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajendra S, et al.23 | 1997–2000 | Chinese, Indian, Malay | 1,985 | Single center | LSBE: 1.6%, SSBE: 4.6% |

| Hongo M, Shoji T8 | 1999–2000 | Japan, Korea, Taiwan | 7,134 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.4%,* SSBE: 0.9%* |

| Wong WM, et al.24 | 1997–2001 | China | 16,606 | Single center | LSBE: 0.02%, SSBE: 0.04% |

| Zhang J, et al.25 | 2001–2002 | China | 391 | Single center | LSBE: 6.6%,* SSBE: 24.0%* |

| Amarapurkar AD, et al.26 | 1997 | India | 150 with FD | Single center | 2.6% |

| Dhawan PS, et al.27 | 2000 | India | 271 | Single center | 5.9% (by 1 biopsy specimen) |

| Punia RS, et al.28 | 1999–2002 | India | 55 with GERD | Single center | 23.6% |

| Bafandeh Y, et al.29 | 2001–2003 | Iran | 1,248 with GERD | Single center | LSBE: 0.8%, SSBE: 1.6%, BE: 8.3%* |

| Rezailashkajani M, et al.30 | 2005–2006 | Iran | 501 | 0.2% | |

| Azuma N, et al.31 | 1996–1998 | Japan | 650 | Single center | LSBE: 0.6%,* SSBE: 15.1%*† |

| Hongo M, Skoji T8 | 1999–2000 | Japan | 18,400 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.2%,* SSBE: 1.0%* |

| Fujiwara Y, et al.32 | 2001–2003 | Japan | 548 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.2%, SSBE: 12.0% |

| Kawano T, et al.33 | 2003 | Japan | 2,577 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.2%,* SSBE: 20.8%*† |

| Amano Y, et al.7 | 2003–2004 | Japan | 1,699 | Single center | LSBE: 0.2%, SSBE: 19.7% LSBE: 0.4%,* SSBE: 37.7%* |

| Lee JI, et al.34 | 2000 | Korea | 1,553 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.32% |

| Kim JH, et al.35 | 1997–2004 | Korea | 70,103 | Multicenter | LSBE: 0.01%, SSBE: 0.14% LSBE: 0.01%,* SSBE: 0.53%* |

| Choi DW, et al.36 | 2002 (publication) | Korea | 847 | Single center | LSBE: 0.5%,* SSBE: 16.5%* |

| Kim JY, et al.37 | 2005 (publication) | Korea | 992 | Multicenter | LSBE : 0.1%, SSBE : 3.5% LSBE: 0.3%,* SSBE: 10.9%* |

| Rosaida MS, Goh KL38 | 2004 (publication) | Malaysia | 1,000 | Single center | 2.0% |

| Gadour MO, Ayoola EA39 | 1999 (publication) | Saudi Arabia | 159 | Single center | 0.3% |

| Yeh C, et al.12 | 1991–1992 | Taiwan | 464 | Single center | 1.98% |

- BE

Barrett esophagus

- FD

functional dyspepsia

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- LSBE

long-segment Barrett esophagus

- SSBE

short-segment Barrett esophagus.

Prevalence of endoscopic Barrett esophagus.

Endoscopic Barrett esophagus diagnosed by palisade vessel criteria.

A multicenter, prospective, nationwide, epidemio-logic study conducted in Japan by the Japanese GERD Society found an overall prevalence of endoscopically suspected Barrett esophagus of 24.1%, of which 99.1% was SSBE.33 Some patients were symptomatic during their annual health check-up, whereas others were asymptomatic. The prevalence of Barrett esophagus was higher in this study than in other studies. Moreover, the diagnostic criteria for endoscopic Barrett esophagus were those widely used in Japan, but not in Western countries. The distal end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels was used to define the gastroesophageal junction.

Endoscopic Diagnosis of Barrett Esophagus

Marked variation in the prevalence of Barrett esophagus in Asian countries may stem from differences in endoscopic diagnostic criteria among studies. In the study by the Japan GERD Society cited above, the endoscopic criteria proposed by the Japan Esophageal Society were utilized.43 In Japan, the distal end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels is believed to coincide with, and is used to define, the esophagogastric junction (EGJ).44–48 In Japan, Barrett esophagus is defined by the presence of columnar epithelium between the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) and the EGJ, irrespective of the type of columnar epithelium and its length (ie, LSBE or SSBE), depending upon the distance of the SCJ from the EGJ.

In Western countries, the landmark for the EGJ is the proximal end of the gastric longitudinal folds. According to the Prague C & M Criteria for Barrett Esophagus, which were proposed by a subgroup of the International Working Group for the Classification of Oesophagitis (IWGCO) in order to standardize the objective diagnosis of endoscopic Barrett esophagus using conventional endoscopy,40 the landmark for the EGJ is the proximal end of the gastric folds. As interobserver disagreement regarding endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus, in particular SSBE, results from the difficulty of determining the location of the EGJ,41,42 the question arises as to which landmark is appropriate: the proximal end of the gastric folds or the distal end of the esophageal palisade vessels?

Usually, palisade vessels can be found easily when the lower esophagus is adequately distended by air insufflation. In cases with superficial dysplastic lesions and/or intense inflammation, palisade vessels sometimes cannot be endoscopically detected, suggesting that the palisade vessels criterion may not be useful for endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus.

On the other hand, an investigation of the Prague C & M Criteria using video clip images of the EGJ found interobserver disagreement in Barrett esophagus cases less than 1 cm in length, but it also found interobserver agreement in Barrett esophagus cases greater than 1 cm.41 Similarly, in our own study, kappa values were higher for endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus longer than 1 cm in length,42 suggesting the unsuitability of the C & M criteria for diagnosing SSBE.

Utilizing only palisade vessels to determine the endoscopic definition of the EGJ resulted in a low kappa coefficient of reliability. When the upper end of the longitudinal gastric folds was used, the diagnostic concordance, though initially low, improved to an acceptable level after the complete application of Prague C & M Criteria for Barrett Esophagus.42 In April 2007, the Japan Esophageal Society added gastric folds as an additional landmark of the EGJ to the guidelines for clinical and pathologic studies on carcinoma of the esophagus.43 Therefore, it is acceptable for Japanese endoscopists to determine the EGJ using both landmarks: the distal end of the palisade vessels and the proximal end of the gastric folds when the palisade vessels are invisible.

Histologic Diagnosis of Barrett Esophagus

Another reason for variation in the prevalence of Barrett esophagus may stem from the lack of a worldwide consensus on the histologic definition of Barrett esophagus. According to the guidelines of the American College of Gastroenterology,1 Barrett esophagus is defined by the change of the esophageal epithelium of any length recognized at endoscopy and histologically confirmed to contain intestinal metaplasia. Furthermore, a definite histologic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus requires proof of intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells. Kerkhof and colleagues showed that intestinal metaplasia can be found easily in biopsy specimens if the length of endoscopic Barrett esophagus is longer than 2 cm.49 However, intestinal metaplasia cannot be found easily in many SSBE cases with uneven distribution of intestinal metaplasia.

According to the proposed guidelines of the British Society of Gastroenterology,2 the presence of specialized columnar epithelium is less important for the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus than the presence of a proper esopha-geal gland, squamous island, and/or double muscularis mucosae.50–53 The efficacy and usefulness of their criteria have also been sufficiently discussed at the Paris Workshop on Columnar Metaplasia in the Esophagus and the Esophagogastric Junction.54 Like the British Society of Gastroenterology, the Japan Esophageal Society defines Barrett esophagus as the presence of at least 1 of the following factors: a proper esophageal gland, squamous island, and double muscularis mucosae.43 Therefore, differences among studies regarding epidemiologic prevalence data for Barrett esophagus may be due to differences among these studies regarding their histologic criteria.

Barrett Esophagus and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Asia

Predictors for the presence of Barrett esophagus include old age, male gender, hiatal hernia, and long-lasting reflux symptoms.16,55–59 Alcohol and smoking have also been reported to be predictors for Barrett esophagus and Barrett cancer in the West,15,18,49,60 but not in Asia.7,35,37

However, hiatal hernia and Helicobacter pylori infection are important predictors for Barrett esophagus in Asia. The presence of hiatal hernia plays an important role for the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis and Barrett esophagus, as hiatal hernia induces long-lasting reflux of gastric acid contents.23,38,61 The prevalence of hiatal hernia increases with age in Japan; hiatal hernia was found in approximately 70% of patients over 70 years of age, as shown in Figure 1.

H. pylori infection is well known to be more prevalent in Asian than in Western countries and to protect against the development of GERD and Barrett esophagus.62–69 In Japan, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was approximately 70% among patients born before 1950.70 The prevalence of H. pylori infection, however, has decreased during the last two decades.71 The gradual decrease of H. pylori seroprevalence was also found in many Asian countries.72–74 H. pylori infection protects against the development of Barrett esophagus via the decrease of gastric-acid secretion. Therefore, the high rate of H. pylori infection is believed to account for the lower prevalence of Barrett esophagus in Asian countries. Vieth and coworkers determined the prevalence of H. pylori infection from a meta-analysis of 23 studies, including their own, and concluded that 35.6% of 2,084 patients with Barrett esophagus in Western countries were infected with H. pylori.75 As shown in Table 2,69,75–83 the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with Barrett esophagus is higher in Asian than in Western countries.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients with Barrett Esophagus in Asian Versus Western Countries

| Study | Study Period | Country | Sample Size (N) | Study Method | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian Countries | |||||

| Abe Y, et al.76 | 1996-2001 | Japan | 112 with RE | Single center | SSBE: 18.7% LSBE: 0% |

| Zhang J, et al.77 | 2001-2002 | China | 375 with GERD | Single center | SSBE: 48.7%, LSBE: 41.8% |

| Amano Y, et al.78 | 2002-2003 | Japan | 400 with BE | Single center | SSBE: 51.2% |

| Chinuki D, et al.79 | 2003-2004 | Japan | 266 with BE | Single center | SSBE: 45.5% |

| Rajendra S, et al.69 | 2003-2005 | Malaysia | 188 with GERD | Single center | SSBE: 72.0%, LSBE: 26.7% |

| Western Countries | |||||

| Vieth M, et al.75 | 1990-1997 | Germany | 1,054 with BE | Single center | 43.9% |

| Loffeld RJ, van der Putten AB80 | 1994-2004 | Netherlands | 11,691 | Single center | 30.7% |

| Wani S, et al.81 | 2000-2002 | US | 46 with BE | Single center | 6.5% |

| Weston AP, et al.82 | 2000 (publication) | US | 289 with BE | Single center | 35.1% |

| Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, et al.83 | 2006 (publication) | Canada | 1,040 | Multicenter | 28.0% |

- BE

Barrett esophagus

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- LSBE

long-segment Barrett esophagus

- RE

reflux esophagitis

- SSBE

short-segment Barrett esophagus.

Schenk and associates found that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was 20.4% and 44.3% in patients with and without Barrett esophagus, respectively.84 Weston and colleagues also found that the incidence of H. pylori infection is related to the incidence of Barrett carcino-genesis (ie, 35.1%, 14.3%, and 15.0% in patients without dysplastic lesion, with high-grade dysplasia, and with Barrett cancer, respectively).82 Moreover, SSBE developed in 10.3% of patients who underwent H. pylori eradication therapy,85 and Barrett esophagus developed after spontaneous healing of atrophic gastritis in patients with H. pylori antibody titers that had fallen to normal levels.86 These findings clearly suggest that H. pylori infection is protective for the development of Barrett esophagus.

Vicari and colleagues reported that cytotoxin-associ-ated gene A (CagA)-positive strains of H. pylori, which are known to induce intense inflammation in the gastric mucosa and are closely correlated with the incidence of gastric carcinogenesis, protect against the development of Barrett esophagus.87 Although the prevalence of H. pylori infection was not significantly lower in patients with Barrett esophagus (approximately 34%) than in the control group, the prevalence of CagA-positive H. pylori infection was significantly decreased in patients with Barrett esophagus (13.3%). This protective effect was confirmed by other investigations in Asian and Western countries.88–91 Thus, it is suggested that H. pylori infection affects the prevalence of Barrett esophagus and may account for the lower prevalence of this disease in Asia than in the West.

On the other hand, several investigators found no relationship between H. pylori infection and the development of Barrett esophagus or Barrett cancer.75,77,92–94 Henihan and coworkers found that H. pylori infection induces severe chronic inflammation in Barrett esophagus and, thereby, is not protective against development of Barrett esophagus.95 Thus, the relationship between H. pylori infection and Barrett esophagus is still ambiguous. Koike and associates demonstrated that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly lower in patients with adenocarcinoma at the EGJ than in patients with gastric cancer, though not as low as in patients with erosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus.96 This finding suggests that preservation of gastric acid secretion may be important for the development of adenocarcinoma at the EGJ, regardless of the presence of H. pylori infection. Thus, a high infection rate of H. pylori does not completely explain the lower prevalence of Barrett esophagus and shorter Barrett segments in Asian than in Western countries.

Issues Related to Incidence of Barrett Esophagus in Asia

According to the comprehensive registry of the Japan Esophageal Society during 1995–1997, esophageal aden-ocarcinoma accounted for only 1.4% of all esophageal cancers.8 However, as GERD is gradually increasing in Asia,97 Barrett esophagus may increase. Most Barrett esophagus in Asia is SSBE, which also has a malignant potential. Therefore, the establishment of strategies for diagnosing and treating Barrett esophagus is an important goal in Asia, as well as in the West.

First, new criteria need to be established for the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus, as the Prague C & M criteria proposed by IWGCO are not helpful for the diagnosis and classification of SSBE.41,42 Second, a systematic method for the endoscopic surveillance of SSBE should also be established. Most Barrett cancer in Asian countries develops from SSBE. Although a stepwise 4-quadrant biopsy procedure is the gold standard for the surveillance of dysplastic Barrett esophagus in many Western countries, it is not an ideal method from the standpoint of safety, labor, or cost-effectiveness, and it should be avoided if guidance methods such as crystal violet chromoendoscopy,98,99 magnifying endoscopy with acetate enhancement100,101 or narrow band imaging,102,103 or autofluorescence endoscopy104 can be used to obtain the target biopsy. Crystal violet chromoendoscopy can detect dysplastic Barrett lesions with high sensitivity and specificity in both LSBE and SSBE cases. Magnifying endoscopy combined with acetate enhancement or narrow band imaging is also useful, though it is time-consuming in LSBE cases. These new endoscopic procedures may have advantages over the random biopsy diagnostic method in Asian patients with SSBE.

Strategies for the treatment and management of Barrett esophagus and the prevention of Barrett cancer should also be established in Asia. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used to shorten the length of Barrett esophagus. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, or selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors are used to prevent Barrett carcinogenesis. PPIs suppress cellular proliferation105,106 and facilitate the regression of Barrett esophagus.107–109 NSAIDs such as aspirin are known to decrease the risk of many types of cancer, and in patients with Barrett esophagus, they decrease the risk of carcinogenesis from Barrett esophagus.6,110–112 Recent studies have discussed the prophylactic effects of selective COX-2 inhibitors for Barrett carcinogenesis.113–115 The efficacy of their drugs must be evaluated in Asian patients with Barrett esophagus, as little data from Asian countries are available.

Conclusion

Barrett esophagus is not rare, even in Asia, where the majority of it is in the form of SSBE. Endoscopic diagnosis of SSBE has several problems, and an endoscopic surveillance policy should be established. As patients with SSBE have a somewhat higher risk for developing cancer, an appropriate treatment strategy for SSBE should also be established in Asia.

Contributor Information

Yuji Amano, Dr. Amano serves as Director and Associate Professor in the Division of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy at Shimane University Hospital in Izumo, Japan..

Yoshikazu Kinoshita, Dr. Kinoshita is the Dean in the School of Medicine at Shimane University in Izumo, Japan, where he also serves as Professor and Chairman in the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology..

References

- 1.Sampliner RE. Practice guidelines on the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett esophagus. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1028–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson A, Heading RC, Shepherd NA, editors. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett columnar-lined oesophagus. A report of the working party of the British Society of Gastroenterology. [December 10, 2007];British Society of Gastroenterology. [web page]. August 2005. Available at http://www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/Bar-retts_Oes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF., Jr Continuing climb in rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma: an update. JAMA. 1993;270:1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guillem P, Billeret V, Buisine MP, Flejou JF, Lecomte-Houcke M, et al. Mucin expression and cell differentiation in human normal, premalignant, and malignant esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:856–861. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001215)88:6<856::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warson C, Van De Bovenkamp JH, Korteland-Van Male AM, Büller HA, Ein-erhand AW, et al. Barrett esophagus is characterized by expression of gastric-type mucins (MUC5AC, MUC6) and TFF peptides (TFF1 and TFF2), but the risk of carcinoma development may be indicated by the intestinal-type mucin, MUC2. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:660–668. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amano Y, Ishihara S, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, Takahashi Y, et al. Barrett oesophagus with predominant intestinal metaplasia correlates with superficial cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression, increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis: changes that are partially reversed by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs usage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, Takahashi Y, Moriyama I, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett esophagus with intestinal predominant mucin pheno-type. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:873–879. doi: 10.1080/00365520500535485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(suppl 15):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnell TG, Sontag SJ, Chejfec G. Adenocarcinoma arising in tongues or short segments of Barrett esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:137–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01308357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drewitz DJ, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in Barrett esophagus: a prospective study of 170 patients followed 4.8 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma P, Morales TG, Bhattacharyya A, Garewal HS, Sampliner RE. Dysplasia in short-segment Barrett esophagus: a prospective 3-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2012–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh C, Hsu CT, Ho AS, Sampliner RE, Fass R. Erosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus in Taiwan: a higher frequency than expected. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:702–706. doi: 10.1023/a:1018835324210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen PH. Review: Barrett oesophagus in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston MH, Hammond AS, Laskin W, Jones DM. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of short segments of specialized intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus on routine endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1507–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirota WK, Loughney TM, Lazas DJ, Maydonovitch CL, Rholl V, Wong RK. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:461–467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RK, et al. Screening for Barrett esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1670–1677. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, Loeb DS, Krishna M, et al. Barrett esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero Y, Cameron AJ, Schaid DJ, McDonnell SK, Burgart LJ, et al. Barrett esophagus: prevalence in symptomatic relatives. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1127–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westhoff B, Brotze S, Weston A, McElhinney C, Cherian R, et al. The frequency of Barrett's esophagus in high-risk patients with chronic GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:226–231. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT. Barrett esophagus: age, prevalence, and extent of columnar epithelium. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1241–1245. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91510-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajendra S, Kutty K, Karim N. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of endo-scopic esophagitis and Barrett esophagus: the long and short of it all. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:237–242. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000017444.30792.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong WM, Lam SK, Hui WM, Lai KC, Chan CK, et al. Long-term prospective follow-up of endoscopic oesophagitis in southern Chinese: prevalence and spectrum of the disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2037–2042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Chen XL, Wang KM, Guo XD, Zuo AL, Gong J. Barrett esophagus and its correlation with gastroesophageal reflux in Chinese. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1065–1068. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i7.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amarapurkar AD, Vora IM, Dhawan PS. Barrett esophagus. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1998;41:431–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhawan PS, Alvares JF, Vora IM, Joseph TK, Bhatia SJ, et al. Prevalence of short segments of specialized columnar epithelium in distal esophagus: association with gastroesophageal reflux. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Punia RS, Arya S, Mohan H, Duseja A, Bal A. Spectrum of clinico-pathologi-cal changes in Barrett oesophagus. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bafandeh Y, Esmaili H, Aharizad S. Endoscopic and histologic findings in Iranian patients with heartburn. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezailashkajani M, Roshandel D, Shafaee S, Zali MR. High prevalence of reflux oesophagitis among upper endoscopies of Iranian patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:499–506. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32811ebfec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azuma N, Endo T, Arimura Y, Motoya S, Itoh F, et al. Prevalence of Barrett esophagus and expression of mucin antigens detected by a panel of monoclonal antibodies in Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:583–592. doi: 10.1007/s005350070057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, et al. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawano T, Kouzu T, Ohara S, Kusano M. The prevalence of Barrett mucosa in the Japanese [in Japanese with English abstract] Gastroenterol Endosc. 2005;47:951–961. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JI, Park H, Jung HY, Rhee PL, Song CW, Choi MG. Prevalence of Barrettesophagus in an urban Korean population: a multicenter study. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:23–27. doi: 10.1007/s005350300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JH, Rhee PL, Lee JH, Lee H, Choi YS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett esophagus in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:908–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi DW, Oh SN, Baek SJ, Ahn SH, Chang YJ, et al. Endoscopically observed lower esophageal capillary patterns. Korean J Intern Med. 2002;17:245–248. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JY, Kim YS, Jung MK, Park JJ, Kang DH, et al. Prevalence of Barrett esophagus in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosaida MS, Goh KL. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, reflux oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a multiracial Asian population: a prospective, endoscopy based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:495–501. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadour MO, Ayoola EA. Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer in Saudi Arabia. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong D. Review article: towards consistency in the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett oesophagitis and columnar metaplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ter. 2004;20(suppl 5):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, Bergman JJ, Gossner L, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amano Y, Ishimura N, Furuta K, Takahashi Y, Chinuki D, et al. Which landmark results in a more consistent diagnosis of Barrett esophagus, the gastric folds or the palisade vessels? Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Japan Esophageal Society. 10th ed. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara Co.; Guidelines for the clinical and pathologic studies on carcinoma of the esophagus. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshihara Y, Kogure T, Yamamoto T, Hoshimoto M, Hoteya O. Endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett esophagus [in Japanese with English abstract] Nippon Rinsho. 2005;63:1394–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoshihara Y, Kogure T. What are longitudinal vessels? Endoscopic observation and clinical significance of longitudinal vessels in the lower esophagus. Esophagus. 2006;3:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Carvalho CA. Sur l'angioarchitecture veineuse de la zone de transition oesophagogastrique et son interpretation functionnelle. Acta Anat. 1966;64:125–162. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noda T. Angioarchitectural study of esophageal varices. With special reference to variceal rupture. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:381–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00695222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vianna A, Hayes PC, Moscoso G, Driver M, Portmann B, et al. Normal venous circulation of the gastroesophageal junction. A route to understanding varices. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:876–889. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerkhof M, Steyerberg EW, Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Predicting presence of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in columnar-lined esophagus: a multivariate analysis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:772–778. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takubo K, Sasajima K, Yamashita K, Tanaka Y, Fujita K. Double muscularis mucosae in Barrett esophagus. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90270-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takubo K, Nixon JM, Jass JR. Ducts of esophageal glands proper and Paneth cells in Barrett esophagus: frequency in biopsy specimens. Pathology. 1995;27:315–317. doi: 10.1080/00313029500169213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long JD, Orlando RC. Esophageal submucosal glands: structure and function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2818–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1422_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takubo K, Vieth M, Aryal G, Honma N, Sawabe M, et al. Islands of squamous epithelium and their surrounding mucosa in columnar-lined esophagus: a pathog-nomonic feature of Barrett esophagus? Hum Pathol. 2005;36:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paris Workshop on Columnar Metaplasia in the Esophagus and the Esopha-gogastric Junction, Paris, France, December 11-12 2004. Endoscopy. 2005;37:879–920. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campos GM, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, Oberg S, Crookes PF, et al. Predictive factors of Barrett esophagus: multivariate analysis of 502 patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1267–1273. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conio M, Filiberti R, Blanchi S, Ferraris R, Marchi S, et al. Risk factors for Barrett esophagus: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:225–229. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Hiatal hernia and acid reflux frequency predict presence and length of Barrett esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:256–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1013797417170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wakelin DE, Al-Mutawa T, Wendel C, Green C, Garewal HS, Fass R. A predictive model for length of Barrett esophagus with hiatal hernia length and duration of esophageal acid exposure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:350–355. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Chejfec G, Metz A, Sontag SJ. Hiatal hernia size, Barrett length, and severity of acid reflux are all risk factors for esopha-geal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1930–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Jonge PJ, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Honkoop P, Wolters LM, et al. Risk factors for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amano K, Adachi K, Katsube T, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. Role of hiatus hernia and gastric mucosal atrophy in the development of reflux esophagitis in the elderly. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:132–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim NY, Kim SW, Kim JG, et al. Seroepidemiological study of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic people in South Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:969–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh V, Trikha B, Nain CK, Singh K, Vaiphei K. Epidemiology of Helico-bacter pylori and peptic ulcer in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:659–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown LM, Tomas TL, Ma JL, Chang YS, You WC, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in rural China: demographic, lifestyle and environmental factors. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:638–645. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan HJ, Rizal AM, Rosmadi MY, Goh KL. Distribution of Helicobacter pylori cagA, cagE and vacA in different ethnic groups in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:589–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jais M, Barua S. Seroprevalence of anti Helicobacter pylori IgG/IgA in asymptomatic population from Delhi. J Commun Dis. 2004;36:132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin HY, Chuang CK, Lee HC, Chiu NC, Lin SP, Yeung CY. A seroepidemio-logic study of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus infection in primary school students in Taipei. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005;8:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan MA, Ghazi HO. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajendra S, Ackroyd R, Robertson IK, Ho JJ, Karim N, Kutty KM. Helico-bacter pylori, ethnicity, and the gastroesophageal reflux disease spectrum: a study from the East. Helicobacter. 2007;12:177–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760–766. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90156-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fujisawa T, Kumagai T, Akamatsu T, Kiyosawa K, Matsunaga Y. Changes in seroepidemiological pattern of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus over the last 20 years in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2094–2099. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, Kim YS, Cho KR, et al. Seroprevalence of Helico-bacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee SY, Park HS, Yu SK, Sung IK, Jin CJ, et al. Decreasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: a 9-year observational study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:630–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen J, Bu XL, Wang QY, Hu PJ, Chen MH. Decreasing seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection during 1993-2003 in Guangzhou, southern China. Helicobacter. 2007;12:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vieth M, Masoud B, Meining A, Stolte M. Helicobacter pylori infection: protection against Barrett mucosa and neoplasia? Digestion. 2000;62:225–231. doi: 10.1159/000007820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abe Y, Ohara S, Koike T, Sekine H, Iijima K, et al. The prevalence of Heli-cobacter pylori infection and the status of gastric acid secretion in patients with Barrett esophagus in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1213–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang J, Chen XL, Wang KM, Guo XD, Zuo AL, Gong J. Relationship of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection to Barrett esophagus and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in Chinese. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:672–675. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, Takahashi Y, Chinuki D, et al. Predictors for squamous re-epithelialization of Barrett esophagus after endoscopic biopsy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:901–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chinuki D, Amano Y, Ishihara S, et al. REG Ia protein expression in Barrett esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04832.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Loffeld RJ, van der Putten AB. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Neth J Med. 2004;62:188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wani S, Sampliner RE, Weston AP, Mathur S, Hall M, et al. Lack of predictors of normalization of oesophageal acid exposure in Barrett oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weston AP, Badr AS, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Dixon A, Hassanein RS. Prospective evaluation of the prevalence of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with GERD Barrett esophagus, Barrett dysplasia, and Barrett adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Tomson AB, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Chiba N, et al. The prevalence of Barrett oesophagus in a cohort of 1040 Canadian primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia undergoing prompt endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:595–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Eskes SA, Meuwissen SG. Helicobacter pylori and the efficacy of omeprazole therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.982_e.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yachida S, Saito D, Kozu T, Gotoda T, Inui T, et al. Endoscopically demonstrable esophageal changes after Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with gastric disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1346–1352. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kokkola A, Sipponen P, Haapiainen R, Rautelin H, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Puolakkainen P. Development of Barrett esophagus after ‘spontaneous’ healing of atrophic corpus gastritis. Helicobacter. 2003;8:590–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2003.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, Easley KA, et al. The seroprevalence of cagA positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chow WH, Blaser MJ, Blot WJ, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, et al. An inverse relation between cag A+ strains of Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Clark GW. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection in Barrett esophagus and the genesis of esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2003;27:994–998. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vaezi MF, Falk GW, Peek RM, Vicari JJ, Goldblum JR, et al. CagA-posi-tive strains of Helicobacter pylori may protect against Barrett esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2206–2211. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ackermark P, Kuipers EJ, Wolf C, Breumelhof R, Seldenrijk CA, et al. Colonization with cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1719–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferrández A, Benito R, Arenas J, García-González MA, Sopeña F, et al. CagA-positive Helicobacter pylori infection is not associated with decreased risk of Barrett esophagus in a population with high H. pylori infection rate. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Quddus MR, Henley JD, Sulaiman RA, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett esophagus. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1007–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Geoffrey WB, Clark GWB. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection in Barrett esophagus and the genesis of esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2003;27:994–998. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Henihan RD, Stuart RC, Nolan N, Gorey TF, Hennessy TP, O'Morain CA. Barrett esophagus and the presence of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:542–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.162_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koike T, Ohara S, Inomata Y, Abe Y, Iijima K, Shimosegawa T. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the status of gastric acid secretion in patients with gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma in Japan. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:61–64. doi: 10.1007/s10787-006-1549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wong BC, Kinoshita Y. Systematic review on epidemiology of gastroesopha-geal reflux disease in Asia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Ishihara S, Yuki T, Miyaoka Y, et al. Crystal violet chromoendoscopy with mucosal pit pattern diagnosis is useful for surveillance of short-segment Barrett esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yuki T, Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Takahashi Y, Ose T, et al. Evaluation of modified crystal violet chromoendoscopy procedure using new mucosal pit pattern classification for detection of Barrett dysplastic lesions. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, Castro J. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: a new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:559–565. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sharma P, Weston AP, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Bhattacharyya A, Sampliner RE. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in Barrett oesophagus. Gut. 2003;52:24–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kara MA, Ennahachi M, Fockens P, ten Kate FJ, Bergman JJ. Detection and classification of the mucosal and vascular patterns (mucosal morphology) in Barrett esophagus by using narrow band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goda K, Tajiri H, Ikegami M, Urashima M, Nakayoshi T, Kaise M. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging for the detection of specialized intestinal metaplasia in columnar-lined esophagus and Barrett adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kara MA, Peters FP, Fockens P, ten Kate FJ, Bergman JJ. Endoscopic video-autofluorescence imaging followed by narrow band imaging for detecting early neoplasia in Barrett esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ouatu-Lascar R, Fitzgerald RC, Triadafilopoulos G. Differentiation and proliferation in Barrett esophagus and the effects of acid suppression. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:327–335. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Amano Y, Chinuki D, Yuki T, Takahashi Y, Ishimura N, et al. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitors for cellular proliferation and apoptosis in Barrett oesophagus with different mucin phenotypes. Aliment Pharmacol Ter. 2006;24(suppl 4):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peters FT, Ganesh S, Kuipers EJ, Sluiter WJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, et al. Endoscopic regression of Barrett oesophagus during omeprazole treatment; a randomised double blind study. Gut. 1999;45:489–494. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wilkinson SP, Biddlestone L, Gore S, Shepherd NA. Regression of columnar-lined (Barrett) oesophagus with omeprazole 40 mg daily: results of 5 years of continuous therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1205–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Srinivasan R, Katz PO, Ramakrishnan A, Katzka DA, Vela MF, Castell DO. Maximal acid reflux control for Barrett oesophagus: feasible and effective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:519–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vaughan TL, Dong LM, Blount PL, Ayub K, Odze RD, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of neoplastic progression in Barrett oesophagus: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:945–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Anderson LA, Johnston BT, Watson RG, Murphy SJ, Ferguson HR, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the esophageal inflammation-metaplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4975–4982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Triadafilopoulos G, Kaur B, Sood S, Traxler B, Levine D, Weston A. The effects of esomeprazole combined with aspirin or rofecoxib on prostaglandin E2 production in patients with Barrett oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:997–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Oyama K, Fujimura T, Ninomiya I, Miyashita T, Kinami S, et al. A COX-2 inhibitor prevents the esophageal inflammation-metaplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:565–570. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lanas A, Ortego J, Sopeña F, Alcedo J, Barrio E, et al. Effects of long-term cyclo-oxygenase 2 selective and acid inhibition on Barrett oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:913–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Heath EI, Canto MI, Piantadosi S, Montgomery E, Weinstein WM, et al. Secondary chemoprevention of Barrett esophagus with celecoxib: results of a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:545–557. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]