Abstract

Previous studies demonstrate the initiation of colon cancers through deregulation of WNT-TCF signalling. An accepted but untested extension of this finding is that incurable metastatic colon carcinomas (CCs) universally remain WNT-TCF-dependent, prompting the search for WNT-TCF inhibitors. CCs and their stem cells also require Hedgehog (HH)-GLI1 activity, but how these pathways interact is unclear. Here we define coincident high-to-low WNT-TCF and low-to-high HH-GLI transitions in patient CCs, most strikingly in their CD133+ stem cells, that mark the development of metastases. We find that enhanced HH-GLI mimics this transition, driving also an embryonic stem (ES)-like stemness signature and that GLI1 can be regulated by multiple CC oncogenes. The data support a model in which the metastatic transition involves the acquisition or enhancement of a more primitive ES-like phenotype, and the downregulation of the early WNT-TCF programme, driven by oncogene-regulated high GLI1 activity. Consistently, TCF blockade does not generally inhibit tumour growth; instead, it, like enhanced HH-GLI, promotes metastatic growth in vivo. Treatments for metastatic disease should therefore block HH-GLI1 but not WNT-TCF activities.

Keywords: colon cancer, Hedgehog-Gli, metastasis, stem cell, Wnt-Tcf

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancers are highly prevalent worldwide with over 1 million new cases yearly and despite numerous efforts the cure rates from metastatic disease are below 5% (e.g. Jemal et al, 2009; Tol et al, 2009). Colon carcinomas (CCs) derive from the intestinal epithelium, which is constantly renewed by the progeny of stem cells residing at the bottom of the crypts of Lieberkühn. Normal intestinal stem cell self-renewal is supported by canonical WNT-TCF signalling. WNT ligands bind the LRP-FRZ receptors and trigger an intracellular signalling cascade that leads to the stabilization of β-catenin (βCAT) through the inhibition of the APC destruction complex, which normally degrades βCAT. TCF factors bound to βCAT then regulate target gene expression in the nucleus (reviewed in MacDonald et al, 2009).

Over 90% of human CCs contain loss-of-function mutations in the APC gene or gain-of-function mutations in βCAT (CTNNB1), leading in all cases to hyperactivity of TCF family transcriptional regulators and tumour formation (reviewed in Hoppler & Kavanagh, 2007). Similarly, direct deregulation of WNT-TCF signalling results in the formation of intestinal adenomas in mice (e.g. MacDonald et al, 2009). It is thought that sustained WNT-TCF activity drives the expansion of CC stem cells, which express the AC133 (CD133+) epitope (O'Brien et al, 2007; Ricci-Vitiani et al, 2007; Zhu et al, 2009), and thus it promotes tumour growth, recurrence and metastases. The requirement of WNT-TCF activity in human CC is further supported by the finding that adenomas display a crypt/adenoma TCF-dependent gene expression signature, e.g. SOX4, LGR5, AXIN2, cMYC (Leung et al, 2002; van de Wetering et al, 2002; van der Flier et al, 2007; Yochum et al, 2007) and that this signature and tumour cell proliferation are abrogated in vitro by the inhibition of TCF function through the expression of dominant-negative TCF (dnTCF4) (van de Wetering et al, 2002). These and other results (reviewed in MacDonald et al, 2009) have spurred major efforts to develop WNT-TCF inhibitors to treat patients with CCs (e.g. Chen et al, 2009; Huang et al, 2009; Lepourcelet et al, 2004).

Another signalling pathway important for CCs is Hedgehog (HH)-GLI (reviewed in Ruiz i Altaba, 2006). Signalling is normally triggered by secreted HH ligands, most often by Sonic HH (SHH), that inactivate the 12-transmembrane protein Patched1 (PTCH1). PTCH1 activity inhibits the function of the 7-transmembrane G-couple-receptor-like protein Smoothened (SMOH). Upon PTCH1 inactivation by HH ligands, SMOH is free to signal intracellularly, involving several kinases and leading to the activation of the GLI transcription factors. Of the three GLI proteins in mice and humans, GLI1 is mostly an activator and acts as the last element of the pathway, activating the expression of targets that include PTCH1, HIP and GLI1 itself. All GLIs have both repressor and activator functions. GLI3 encodes the strongest repressor in its proteolytically processed C′Δ form (GLI3R), which antagonizes HH signalling. In the absence of HH ligands or pathway activating mutations, GLI3R is dominant, and GLI1 is not transcribed. Upon SMOH activation, the GLI code is switched so that GLI1 is transcribed and GLI3R formation repressed (reviewed in Ruiz i Altaba, 2006).

We have recently shown that HH-GLI is essential for the proliferation and survival of primary human CCs of all stages (see Varnat et al, 2009 and references therein). HH-GLI is active in CC epithelial cells and affects both tumour growth and CD133+ cancer stem cells. Interestingly, we detected an increase in the levels of expression of HH-GLI signalling components in advanced and metastatic CCs, and their increased dependence on HH-GLI pathway activity, as compared with non-metastatic CCs (Varnat et al, 2009).

How the HH-GLI and WNT-TCF pathways control the growth and progression of human CCs is not known. Our previous genetic analyses using Apc/Smo conditional mutant mice suggested that Hh-Gli acts in parallel or downstream of βCat/Tcf in intestinal tumorigenesis (Varnat et al, 2010; see also Arimura et al, 2009). Here we have analyzed changes in these pathways directly in patient-derived CCs and their CD133+ CC stem cells, and investigate the possible interactions between HH-GLI, TCF and oncogenic/tumour suppressor inputs important for CCs.

We find that non-metastatic CCs harbour an adenoma-like high WNT-TCF signature but that, surprisingly, metastatic CCs show repressed WNT-TCF and enhanced HH-GLI pathway levels. This metastatic transition is recapitulated in advanced CCs grown in vitro, in which a high WNT-TCF non-metastatic state is imposed, versus in vivo in xenografts, which faithfully mimic advanced tumours in patients and display a high HH-GLI and low WNT-TCF state. Repression of WNT-TCF signalling in advanced and metastatic cancers is critical as suggested by the finding that blockade of TCF activity generally inhibits CC growth in vitro, but not in vivo where it can, in fact augment tumor growth. Importantly, we show that TCF blockade in vivo generally enhances CC metastases.

Analyses of interactions of GLI1 with WNT-TCF, and with CC oncogenes and tumour suppressors, allow us to propose a model in which it is the oncogene- and tumour-suppressor-loss-driven boosting of GLI1 above a threshold during CC progression that drives a pathway switch and the metastatic transition. HH-GLI1, but not WNT-TCF, also regulates an embryonic stem (ES) cell-like signature, prevalent in all CD133+ CC stem cells, that is akin to that involved in reprogramming differentiated cells to an induced pluripotent cell state (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al, 2007). We suggest that enhanced GLI1 levels drive the acquisition of a reprogrammed-like, ES-like, metastatic state that involves repression of WNT-TCF activity. Taken together, the data support interference with HH-GLI, but not WNT-TCF, as a therapeutic strategy against advanced and metastatic CCs, which remain a large unmet medical need.

RESULTS

The presence of metastases in patients is marked by the downregulation of WNT-TCF and enhancement of HH-GLI signatures in CD133+ CC cells

To begin to compare the WNT-TCF and HH-GLI pathways in human CCs we tested for the expression levels of a WNT-TCF gene signature archetypal of crypts and adenomas in relation to the profile of a canonical HH-GLI signature during tumour progression (Varnat et al, 2009). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (after reverse transcription) qRT-PCR was performed on messenger RNAs (mRNAs) directly extracted from freshly sorted CD133+ and CD133− populations from a panel of tumours directly obtained from patients and processed immediately after reception. This contained 34 samples including 24 unselected fresh non-metastatic (tumour-node-metastasis (TNM stages 1,2) and metastatic (TNM3,4) CCs, as well as CC liver metastases (see Supporting information and Varnat et al, 2009 for tumour descriptions). While these cell populations are not homogenous and the CD133− pool includes stromal cells, CD133+ cells are epithelial and enriched for CC stem cells. Normalized gene expression levels are shown individually for selected genes (Figs 1A; S1) and as ratios of normalized values in CD133+ cells over normalized values in the corresponding CD133− cell population (Figs 1B and C; S2).

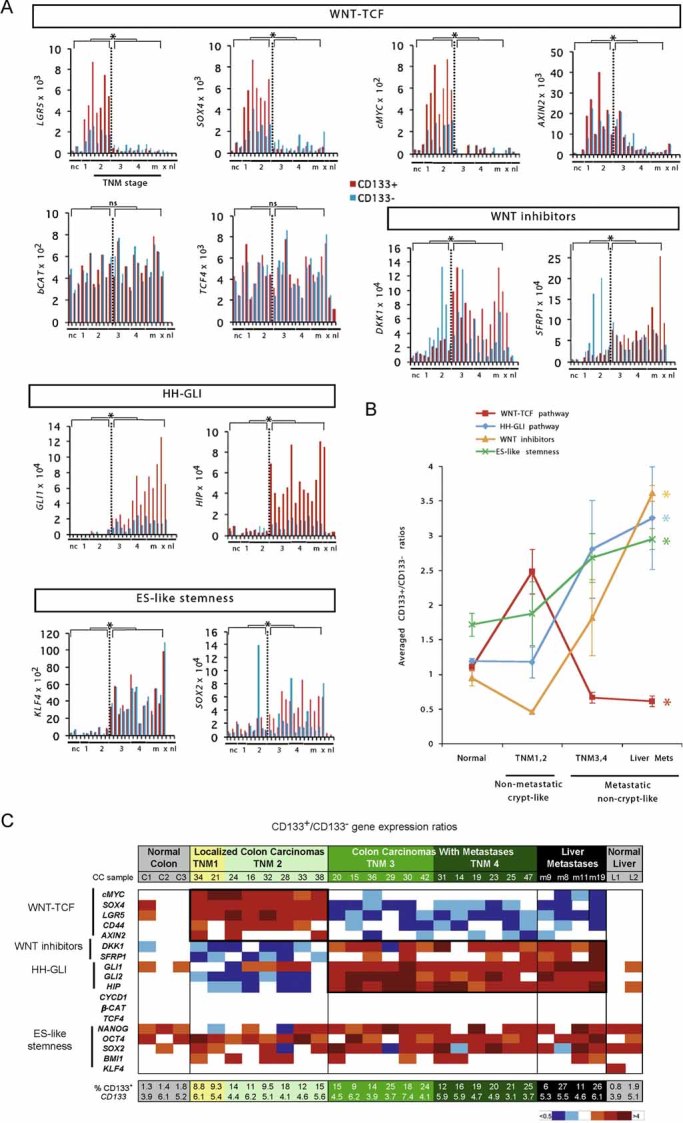

Figure 1. Repressed WNT-TCF and enhanced HH-GLI characterize the metastatic transition of human CCs detected in fresh patient samples.

- Histograms of individual changes in gene expression determined by qRT-PCR in individual patient tumour samples, obtained from the operating room, for both CD133+ (red bars) and CD133− (blue bars) cells of each sample for WNT-TCF, HH-GLI, ES-like stemness and WNT-inhibitors (additional genes are shown in Fig S1 and in Varnat et al, 2009). CCs are grouped by TNM stage (numerals) plus liver metastases (m). Normal colon (nc) and normal liver (nl), and subcutaneous xenografts (x; mCC17) are also included. Description of tumours is as in Varnat et al (2009). Values for GLI1 and HIP are from Varnat et al (2009) shown here for comparison. In all cases ct expression levels are normalized by the geometric mean of the ct values of the EEFIA1 and GAPDH, yielding relative expression levels. Statistics comparing TNM1,2 versus TNM3,4 plus liver metastases are shown by the brackets above each graph. Error bars of s.e.m.'s are not included to enhance clarity. However, asterisks show significance (p < 0.05) using the Student's t-test between CD133+ (red columns) values of TNM1,2 versus those of TNM3,4+ metastases. ns: not significant. In addition, we provide individual comparisons of TNM1,2 versus TNM3,4 and statistics: the CD133+/CD133− ratios were: LGR5: 3.2 in TNM1,2 versus 0.5 in TNM3,4, p < 0.001; SOX4: 2.7 versus 0.4, p < 0.001; cMYC: 3.1 versus 0.8, p < 0.001; DKK1: 0.4 versus 2.3, p < 0.001; SFRP1: 0.4 versus 1.3, p < 0.01; SOX2: 1.4 versus 3.3, p = 0.03; AXIN2, a direct TCF target (e.g. Leung et al, 2002), displayed a decreasing trend in both populations but significantly only in CD133+ cells (19.9 vs. 6.5, p < 0.01); KLF4 showed increased expression in both CD133+ and CD133− populations in metastatic versus non-metastatic CCs: 7.7-fold increase in CD133+ cells of TNM1,2 versus TNM3,4, p = 0.003; eightfold for CD133− cells, p < 0.0001. Ls = LS174T, HT = HT29. Analyses of gene expression in the GEO database was uninformative since there is no data on CD133+ cells and CCs are not TNM sorted.

- Graphic representation of the changes in HH-GLI, WNT-TCF, ES-like stemness and WNT inhibitor signatures in normal colon and during CC progression shown in (Figs 1A; S1). The signatures shown are the averages of the CD133+/CD133− ratios of GLI1, GLI2, PTCH1, SHH, HIP and SNAIL1 for HH-GLI; of cMYC, CD44, LGR5, AXIN2 and SOX4 for WNT-TCF; of NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 for ES-like stemness and of DKK1 and SFRP1 for WNT inhibitors. Asterisks denote significant changes (p < 0.05) between the values of TNM1,2 versus those of liver metastases as indicated by the colour code of the asterisks (e.g. red for HH-GLI).

- Heat map representation of individual gene expression levels determined by qRT-PCR shown in (Figs 1A; S1) in normal and cancer samples shown as CD133+/CD133− ratios. White boxes denote values within the 0.7–1.4 ratio range (see Fig S2). Other colours follow the code given below the table. All values are given in Fig S2. The pathway level switch at the metastatic transition from a high-to-low crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF signature in TNM1,2 CCs, to a low-to-high HH-GLI signature in TNM3,4 and liver metastases is highlighted by bold boxes. HH-GLI data is derived from (Varnat et al, 2009). Note that the signatures of xenografts mimic those of advanced TNM3,4 CCs. The percentage of CD133+ cells in each sample is also given at the bottom of the table, as is the normalized CD133+/CD133− expression ratio of CD133 mRNA.

The expected high expression of key components of a crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF signature (LGR5, SOX4, AXIN2, cMYC and CD44) (Barker et al, 2007; van de Wetering et al, 2002; van der Flier et al, 2007; Yochum et al, 2007) was detected in CD133+ cells of all early, non-metastatic TNM1,2 CCs compared with those of normal colon and liver (Figs Fig 1A–C; S1 and 2).

Surprisingly, WNT-TCF levels significantly decreased ∼3–6-fold in all metastatic TNM3,4 CCs and remained low in all liver metastases in both CD133+ and CD133− cells (Figs 1A–C; S1 and 2). This was not due to the downregulation of βCAT or TCF expression (Fig 1A and C; S2) and was uncoupled from CYCD1 (Figs S1 and 2). The repression of the crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF signature exactly correlated with the upsurge in the levels of the HH-GLI signature (2–10-fold as measured by GLI1, HIP and PTCH1) (Figs 1A–C; S1 and 2; see Varnat et al, 2009).

To extend these results we tested two additional proven WNT-TCF signature genes (Yochum et al, 2007), WNT2 and DVL3, in a group of ten CCs from the above set but also in four additional fresh CCs from patients, one from each TNM stage. The expression of these two genes was consistently repressed in metastatic versus non-metastatic CCs (Figs S1 and 2). Taken together, our data uncover a novel molecular transition coincident with the development of patient metastases that is characterized by changes in the expression of WNT-TCF and HH-GLI signatures mostly, but not exclusively, in CD133+ cells (Figs 1A; S1).

Upregulation of WNT inhibitors in patient metastatic tumours

Since APC mutant CC cells remain WNT ligand-dependent and adenomas and early CCs harbour epigenetically silenced DKK1 and SFRP1 WNT antagonists (González-Sancho et al, 2005; MacDonald et al, 2009; Niida et al, 2004; Suzuki et al, 2004), we tested whether these WNT signalling inhibitors would also be upregulated at the metastatic transition we describe above in patient samples. Advanced metastatic CCs (TNM3,4 and liver metastases) displayed higher levels of DKK1 and SFRP1 than non-metastatic CCs (∼3–6-fold higher; Figs Fig 1A–C; S2), most notably in CD133+ cells, supporting WNT-TCF repression in advanced, metastatic CCs.

Upregulation of part of an ES-like signature in patient metastatic tumours

In addition to known HH-GLI and WNT-TCF pathway components and targets, we have measured by qRT-PCR the levels of an ES cell-like signature we previously described in human glioma stem cells (Clement et al, 2007; Zbinden et al, 2010). The core of this signature is formed by NANOG, OCT4 and SOX2, as in ES cells (Boyer et al, 2005), but the signature also contains other stemness genes such as KLF4 and BMI1 (Clement et al, 2007), and resembles a reprogramming gene set involved in inducing an ES-like state in differentiated cells (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al, 2007). ES-like signature components were enriched in CD133+ versus CD133− cells in all cases (Fig 1C) supporting their use as stemness markers. Overall, the average of the ES-like signature was slightly (∼1.5-fold) but significantly enhanced in CD133+ versus CD133− cells of advanced and metastatic CCs as compared with non-metastatic CCs (Figs 1A–C; S1): NANOG, OCT4 and BMI1 showed minor changes (Figs Fig 1C; S1), but SOX2 and KLF4 clearly increased in both CD133+ and CD133− cells in metastatic versus non-metastatic CCs (∼2–8-fold; Fig 1A–C). Since SOX2 and KLF4 increased in both populations, these increases were not evident in the heatmap showing CD133+ over CD133− ratios (compare Fig 1A vs. 1C).

HH-GLI is epistatic to WNT-TCF function in CC cells in vitro

What drives the changes in gene expression we describe above at the metastatic transition? To investigate possible interactions between CC pathways and oncogenes that might explain the gene expression level changes we observe at the metastatic transition, we first modified the activities of HH-GLI and WNT-TCF in vitro in a number of primary CCs and in the Ls174T cell line, used as a standard in the field (e.g. van de Wetering et al, 2002), and scored the resulting phenotypes, and then tested the ability of several CC oncogenes and tumour suppressors to modify the levels or activity of GLI1.

To block TCF function we have used a modified version of dnTCF fused to the oestrogen receptor ligand binding domain (ERT2) thus rendering it dependent on the addition of the oestrogen analogue tamoxifen (TAM). Inhibition of endogenous TCF activity by TAM-induced dnTCF4ERT2 abolished colony formation of stably transfected CC Ls174T cells (Fig 2A). Similarly, the proliferation of all tested CC cells in vitro, as monolayers or in 3-dimensional collagen gels, was inhibited by dnTCF4 (Fig S3A and B), perfectly reproducing previous data (e.g. van de Wetering et al, 2002).

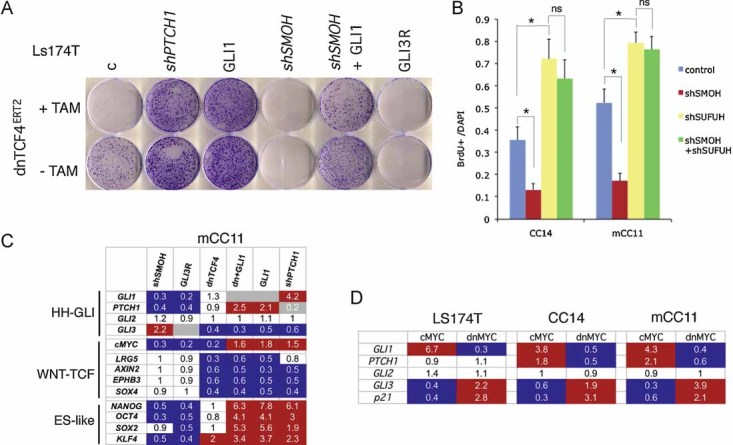

Figure 2. Effects of modulating WNT-TCF and HH-GLI levels in CC cells.

- Images of Ls174T-dnTCF4ERT2 colonies on plates after staining with crystal violet. Cells were transduced with lentivectors as noted. Addition of TAM (+TAM) activated dnTCF4ERT2 and is compared with mock-treated cells (−TAM). Control cells (c) were transduced with GFP-only parental lentivectors. Control assays were also performed with the ERT2 part only ±TAM confirming that ERT2 or TAM per se had no adverse effects (not shown). Quantification is shown in Fig S4A.

- Quantification of the rescue of the anti-proliferative effects, shown as BrdU+ nuclei/total DAPI-labelled nuclei counted per field, of shSMOH by concomitant inhibition of the GLI inhibitor SUFUH through expression of shSUFUH. Results in two primary CCs are shown as indicated. >10 fields were counted per condition. Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests. ns: not significant. Error bars represent s.e.m.

- Heat map of early (16 h) changes of selected key genes for HH-GLI, WNT-TCF and ES-like stemness signatures in mCC11 cells determined by qRT-PCR after expression of cDNAs or shRNAs as indicated. Values are ratios of individual experimental over control (GFP-only transfected cells) values after normalization. Results for CC14 and Ls174T are shown in Fig S4B. White boxes represent ratio values within the 0.7–1.4 range. Blue boxes represent ratio values equal to or smaller than 0.5. Red boxes represent values equal to or greater than 1.5.

- Positive regulatory loop between GLI1 and cMYC. mRNA expression levels determined by qRT-PCR are shown as ratios over control transfected (GFP only) cells. Heat map colours and values are as in (C). Enhanced cMYC levels were obtained by its overexpression while blockade of endogenous cMYC activity was obtained through the expression of dnMYC (also known as OMOMYC; Soucek et al, 2002). Note the general differential regulation of GLI1 and PTCH1 versus GLI3 and p21, the latter being a proven cMYC target. GLI2 levels were unaffected. The lack of upregulation of PTCH1, a GLI1 target (Agren et al, 2004), when GLI1 is upregulated by cMYC in Ls174T cells may be due to different target response kinetics (see Zbinden et al, 2010).

HH-GLI1 pathway blockade by knockdown of SMOH with a specific shRNA (shSMOH; Clement et al, 2007), or by expression of a complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding for GLI3R (Varnat et al, 2009) abolished Ls174T colony formation (Figs 2A; S4A). Conversely, enhanced activation of HH-GLI with shPTCH1 (Varnat et al, 2009) or by enhanced expression of GLI1 (Stecca et al, 2007) increased colony number ∼5-fold (Figs 2A; S4A). Specificity is supported by the finding that enhanced expression of GLI1 or knockdown of suppressor of fused with shSUFUH, which targets a key negative regulator of GLI function (Svärd et al, 2006), rescued the effects of pathway blockade by shSMOH (Fig 2A and B).

Strikingly, both GLI1 and shPTCH1 rescued the inhibitory effect of dnTCF4 (Figs 2A; S4A). This suggests that HH-GLI acts downstream or in parallel to WNT-TCF and that enhanced HH-GLI bypasses the requirement for WNT-TCF function.

Interactions between WNT-TCF and HH-GLI revealed by target gene expression

Early gene expression changes were monitored by qRT-PCR after WNT-TCF and/or HH-GLI pathway modulation in primary (passage 3–6) local CC (CC14; TNM4), CC liver metastatic (mCC11) and CC cell line (Ls174T) cells. Blockade of endogenous WNT-TCF signalling by dnTCF4 resulted in the inhibition of a crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF signature by dnTCF4, as expected (van de Wetering et al, 2002), but it did not decrease the expression of the bona fide HH-GLI pathway activity markers GLI1 and PTCH1 (Figs 2C; S4B). In turn, blockade of endogenous HH-GLI by shSMOH or GLI3R repressed GLI1 and PTCH1, as expected (Clement et al, 2007; Varnat et al, 2009), but it did not inhibit WNT-TCF targets (Figs 2C; S4B), suggesting that, in vitro, WNT-TCF and HH-GLI act in parallel.

In contrast to the results with the blockade of endogenous activities, enhanced HH-GLI activity with GLI1 or shPTCH1 (∼2–4-fold as measured by GLI1 or PTCH1 levels) (Figs 2C; S4B) resulted in the repression of WNT-TCF targets, further suggesting that enhanced HH-GLI can dispense with WNT-TCF activity. Transcription of GLI3 was also repressed by enhanced HH-GLI activity with GLI1 or shPTCH1 (Figs 2C; S4B), but induced by pathway blockade with shSMOH in multiple CC cells tested (Figs 2C; S4B), as expected (e.g. Varnat et al, 2009). Moreover, GLI3 was also repressed by blockade of WNT-TCF function with dnTCF4 in agreement with it being a WNT-TCF target in the CNS (Alvarez-Medina et al, 2008).

The core ES-like stemness signature is regulated by HH-GLI but not WNT-TCF

The expression of the ES-like signature components NANOG, SOX2, OCT4 and KLF4 was detected in all CCs tested (Figs 2C; S4B). Interestingly, they were found to require endogenous HH-GLI activity as revealed by pathway blockade with shSMOH or GLI3R, and its levels were boosted by enhanced HH-GLI function by expression of GLI1 or shPTCH1 (Figs 2C; S4B). In contrast, they were unaffected by blockade of endogenous WNT-TCF signalling by dnTCF4 (Figs 2C; S4B). We conclude that HH-GLI, but not WNT-TCF, regulates the ES-like stemness signature of human CCs.

cMYC is regulated by WNT-TCF and HH-GLI and establishes a positive loop with GLI1 in vitro

cMYC has been described as a key WNT-TCF target required for intestinal tumour formation in mice (Sansom et al, 2007). We therefore analyzed its expression in human CCs and changes in its mRNA levels after WNT-TCF or HH-GLI pathway modulation. The blockade of either WNT-TCF or HH-GLI signalling strongly decreased the expression of cMYC as measured by qRT-PCR (Fig 2C), suggesting a convergence of HH-GLI and TCF on cMYC in vitro. Interestingly, GLI1 generally rescued the inhibition of cMYC by dnTCF4 (Figs 2C; S4B), consistent with the colony assay rescue (Fig 2A), and enhanced HH-GLI pathway activity by GLI1 or shPTCH1 enhanced cMYC levels in mCC11 cells (Fig 2C).

The phenotypic (Fig 2A and B) and gene expression (Fig 2C) analyses described above raised the possibility that WNT-TCF and HH-GLI, which act in parallel in vitro, can functionally interact. To test this idea we have first analyzed an influence of cMYC, a WNT-TCF- and HH-GLI-regulated gene (see above) on GLI1 since cMyc can regulate Gli1 in mouse NIH3T3 cells (Zwerner et al, 2008). Enhanced expression of cMYC by transfection of a cMYC cDNA plasmid in CCs led to an increase in GLI1 levels as determined by qRT-PCR (Fig 2D). More importantly, we could demonstrate that endogenous GLI1 expression in CC cells in vitro requires endogenous MYC activity as revealed by blockade of endogenous cMYC with a dominant-negative construct (dncMYC) (Fig 2D). These results, and the finding that cMYC did not affect GLI-luciferase reporter activity by exogenous GLI1 (Fig S5), suggest that GLI1 and cMYC form a positive transcriptional regulatory loop but that cMYC does not affect the activity of GLI1 protein. Unlike GLI1, GLI2 expression was largely unchanged whereas GLI3 was repressed by cMYC and derepressed by dnMYC to a similar extent than the bona fide CC cMYC target p21 (Fig 2D). In vitro, cMYC thus appears to boost positive GLI activity by upregulating GLI1 mRNA levels but also by repressing GLI3 mRNA expression and thus any derived GLI3R.

βCAT induces GLI1 activity and is mutually antagonistic with GLI3R

In addition to cMYC, we have analyzed possible functional interactions of HH-GLI with other CC oncogenes starting with βCAT, the quintessential oncogene of CCs. Enhanced expression of oncogenic βCAT induced GLI1 activity in a GLI-binding site-luciferase reporter assay in a dose-dependent manner both in whole and in magnetic-activated cell sorted (MACS) CD133+ CC stem cell populations (Figs 3A and B; S6A and B). This effect was also observed in the presence of dnTCF (Figs 3B; S6B), suggesting that the action of βCAT on GLI1 is independent of TCF function. Oncogenic βCAT similarly enhanced the activity of a nuclear SV40NLS-GLI1 fusion, but not of a VP16-GLI1 zinc finger domain fusion (Ruiz i Altaba, 1999), or of the full-length GLI3 weak activator (Fig 3C). These results are important as they indicate nuclear action and specificity.

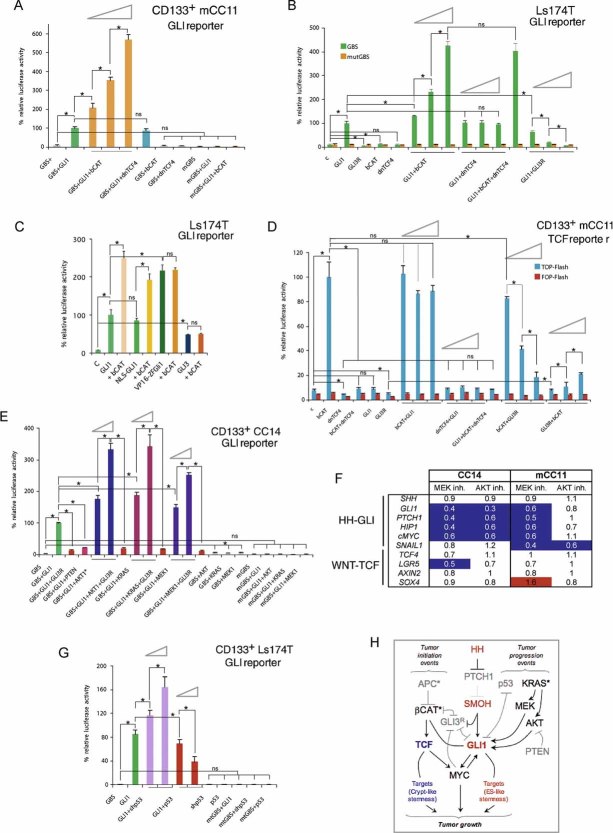

Figure 3. Regulatory HH-GLI and WNT-TCF interactions and modulation of GLI1 activity by CC oncogenes and tumour suppressors.

A,B. GLI-dependent luciferase assays in purified CD133+ mCC11 (A) and Ls174T (B) cells as indicated with wt or mutant (mGBS) reporters. Assays with CC14 and its CD133+ population are shown in Fig S6. Triangles in this and other panels show dose-dependent effects with increasing concentrations of the second plasmid as written in the figures (e.g. GLI1 + βCAT under the left triangle in A have increasing amounts of βCAT with constant amounts of GLI1 plasmids).

C. GLI-dependent luciferase assay showing βCAT (bCAT) action on chimeric GLI1 proteins. See text for details.

D. TCF-dependent luciferase reporter assays using wt (TOP) or mutant (FOP) reporters as indicated in CD133+ mCC11 cells. Similar results with CC14, CD133+ CC14 and Ls174T cells are shown in Fig S7A–C.

E. GLI-dependent luciferase reporters testing for the regulation of GLI1 activity by oncogenic KRAS (KRASV12G), MEK1 (p45MAPKKS222D) and AKT1 (N-myristoylated AKT1). Similar results in CD133+ mCC11 cells are shown in Fig S8.

F. Changes in the expression of key HH-GLI and WNT-TCF pathway genes as determined by qRT-PCR in CC14 and mCC11 after inhibition of endogenous MEK1 activity with U0126 or endogenous AKT activity with SH6 (10 µM, 48 h). Expression values were normalized with housekeeping genes as in Fig 1 and the ratios of the experimental over control mock-treated cells are shown. White boxes denote values within the 0.7–1.4 range. Blue boxes with values equal to or smaller than 0.5. Red boxes with values equal to or greater than 1.5.

G. GLI-dependent luciferase reporters testing for the modulation of GLI1 by increased exogenous p53 and by inhibition of endogenous p53 activity with shp53 as noted, using also mutant (mt) reporters.

H. Scheme of the proposed interactions between WNT-TCF, HH-GLI, oncogenes and tumour suppressors in CC cells as determined in vitro.

Plasmids were nucleofected at similar concentrations unless noted by triangles, where  ,

,  and 1/1 ratios were used for the plasmid in second position. Percent changes in relation to the GLI1 value (equated to 100%, all after normalization with the renilla internal control) are shown (A–C, E and G). Percent changes in relation to the βCAT value are shown in (B and D). ns: difference not significant between the samples at the end of the line. Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests. Error bars represent s.e.m.

and 1/1 ratios were used for the plasmid in second position. Percent changes in relation to the GLI1 value (equated to 100%, all after normalization with the renilla internal control) are shown (A–C, E and G). Percent changes in relation to the βCAT value are shown in (B and D). ns: difference not significant between the samples at the end of the line. Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests. Error bars represent s.e.m.

Although previous work has suggested the inhibition of GLI1 activity by TCF (Akiyoshi et al, 2006), we were unable to reproduce such effect (Figs 2C, 3A and B; S4B and S6). Other work has also highlighted an antagonism between GLI3R and βCAT (Ulloa et al, 2007). In this case, we could reveal their dose-dependent mutual antagonism on TCF activity as shown in TCF binding site-luciferase (TOP) reporter assays in whole and in CD133+ populations (Figs 3D; S7A–C).

As controls we showed that endogenous HH-GLI1 activity was also present in CCs (Varnat et al, 2009), and measured endogenous TCF activity in luciferase reporter assays, finding that it was ∼2-fold in mCC11 cells and 3-fold over background in CC14 cells (Figs 3D; S7C). TCF activity was low or absent in CC14 CD133+ cells as compared with the unsorted population, where it was repressed by dnTCF (Fig S7A and D). Additional controls showed that mutant GLI (GLImut) or TCF (FOP) reporters were inactive (Figs 3A, B, D, E and G; S5–8).

Taken together, our data suggest that βCAT can independently induce both positive TCF and GLI1 activities, and antagonize any GLI3R function, in the tumour bulk and in its CD133+ stem cells (Fig 3H).

GLI1 activity is regulated by RAS-MEK/AKT, PTEN and p53 in CCs

In addition to βCAT, loss of function of the tumour suppressor p53, and gain of oncogenic KRAS mutations are common events during CC progression (Vogelstein et al, 1988). To test if these events could affect GLI1 activity in CC cells as they do in other cancer cells (Stecca & Ruiz i Altaba, 2010; Stecca et al, 2007), we tested the effects of enhanced expression of oncogenic KRAS (KRASV12G) and the downstream components MEK1 (p45MAPKKS222D) and AKT1 (N-myristoylated AKT1) on GLI1 activity using GLI-luciferase reporter assays. RAS, MEK and AKT enhanced GLI1 activity in a dose-dependent manner in different CCs and their CD133+ subpopulations (Figs 3E; S8). As controls, oncogenic KRAS-, AKT- and MEK-induced GLI1 activity levels were fully repressed by GLI3R, and mutant reporters were inactive (Figs 3E; S8).

To test if endogenous RAS-MEK signalling was required for endogenous GLI1 activity in CC cells, we blocked the activities of MEK1 with the small molecule inhibitor U0126 or of AKT with the SH6 inhibitor both at 10 µM for 48 h. Both treatments lead to the repression of GLI1, PTCH1, HIP and cMYC in CC14 cells as measured by qRT-PCR, whereas these were only repressed by MEK blockade in mCC11 cells, all as compared with control DMSO-treated cells (Fig 3F). Moreover, both MEK and AKT inhibitors repressed the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and CC metastatic cell marker SNAIL1 only in metastatic mCC11 cells (Fig 3F). These treatments did not affect the expression of SHH or of the WNT-TCF signature (Fig 3F), supporting the specific requirement of endogenous MEK/AKT signalling downstream of oncogenic RAS for endogenous GLI1 function in CCs. Consistently, exogenous GLI1 activity was also repressed by PTEN, a major tumour suppressor and inhibitor of AKT (Figs 3E; S8).

Along with PTEN, p53 is an important CC tumour suppressor that regulates GLI1 activity in other contexts (Stecca & Ruiz i Altaba, 2009, 2010). Knockdown of endogenous p53 with shp53 increased whereas exogenous p53 decreased GLI1 activity in CD133+ Ls174T (p53 wt) cells in a dose-dependent manner as revealed in GLI-luciferase reporter assays (Fig 3G). p53 and shp53 were ineffective on GLI1 using mutant reporters (Fig 3G). GLI1 levels and activity can thus be modulated by multiple oncogenic and tumour suppressor inputs in CC cells (Fig 3H).

Differential regulation of WNT-TCF and HH-GLI by the microenvironment

The results presented above derive from cells that have high WNT-TCF signatures (Fig 1). However, advanced CCs and liver metastases in patients harbour repressed WNT-TCF signature levels, raising the possibility that the microenvironment may affect pathway use. To test this idea we compared the in vitro gene expression signatures presented above with those present in sibling cells engrafted in immunocompromised mice. The analyses were carried out both with sorted CD133+ and CD133− cells after in vitro culture and from dissected xenografts.

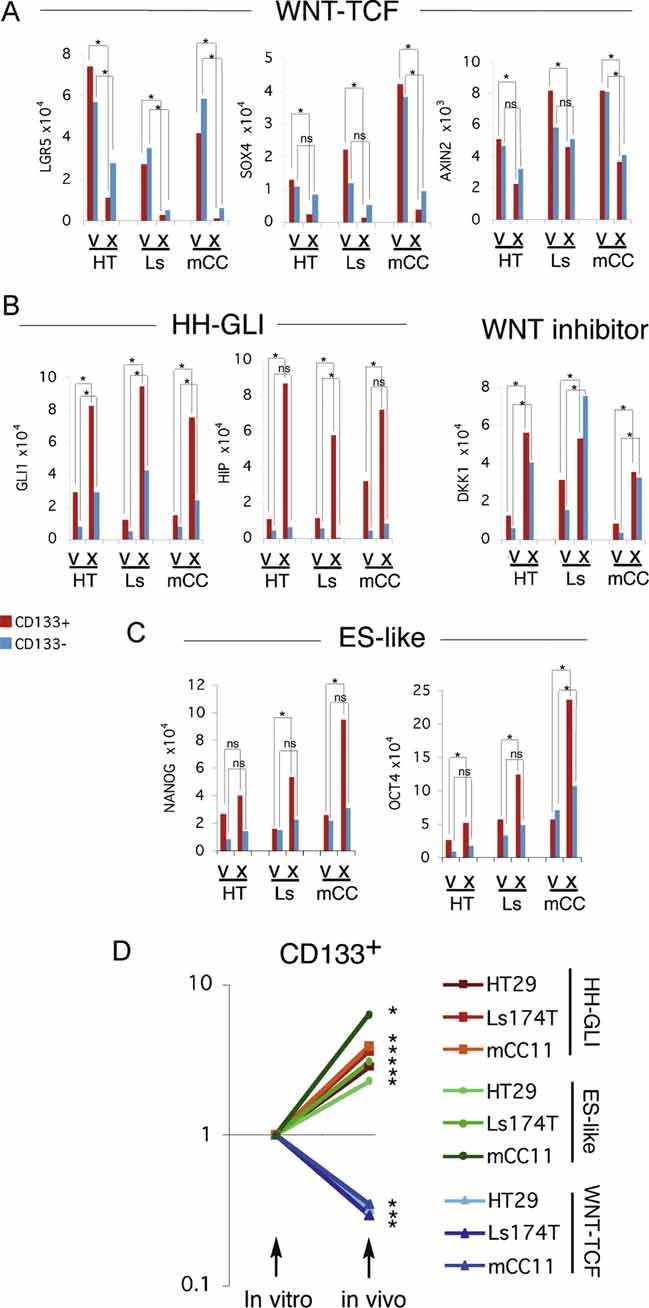

Analyses of HT29, Ls174T, DLD1 CC cell lines and primary mCC11 CC cells revealed that the high expression of WNT-TCF signature components (e.g. LGR5, SOX4, AXIN2, CD44, cMYC) characteristic of crypts/adenomas (van de Wetering et al, 2002) was generally repressed in vivo as compared with the same signature present in sibling cells grown in vitro, especially in CD133+ cells (Figs 4A–C; S9). Conversely, an extended HH-GLI signature (GLI1, GLI2, HIP, SNAIL1, PTCH1, SHH) and core ES-like (NANOG, OCT4, SOX2) signatures were generally enhanced in vivo versus in vitro, consistent with the regulation of ES-like stemness signature by HH-GLI, but not WNT-TCF, with expression level differences being also highest in CD133+ cells (∼3–8-fold) (Figs 4A–C; S9). The opposite changes of WNT-TCF versus those of HH-GLI and ES-like stemness signatures were clearly displayed in plots averaging gene expression levels of individual signatures in CD133+ cells in which in vitro values were equated to 1 for normalization (Fig 4D). Consistent with the in vitro-to-in vivo switch of high-to-low WNT-TCF, the expression of the WNT-LRP inhibitor DKK1 also increased (∼2–4-fold) in vivo versus in vitro, whereas the levels of βCAT and TCF4 did not show consistent changes in vitro versus in vivo (Fig S9).

Figure 4. Differential expression of WNT-TCF and HH-GLI pathway components in CC cells in vitro versus in vivo in xenografts.

A–C. Histograms of individual gene expression changes determined by qRT-PCR for CD133+ (red bars) and CD133− (blue bars) cells, after normalization as in Fig 1, shown for selected WNT-TCF (A), HH-GLI (B) and ES-like stemness genes (C) in HT: HT29; Ls: Ls174T; mCC: mCC11 cells. v: in vitro culture; x; in vivo xenografts. Analyses of additional genes are shown in Fig S9. Error bars of s.e.m.'s are not included to enhance clarity. However, asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests using PCR triplicates in each case. ns: not significant.

D. Logarithmic scale representation of averaged gene expression changes in CD133+ cells (cell lines Ls174T and HT29, and primary mCC11) cultured in vitro versus in vivo in xenografts. Primary data derived from (A) and Fig S9. The values for HH-GLI, βCAT/TCF and ES-like stemness signatures represent the averages, after normalization of the values of GLI1, GLI2, HIP and PTCH1 for HH-GLI, of LGR5, SOX4, AXIN2, cMYC and CD44 for WNT-TCF, and of NANOG, SOX2 and OCT4 for ES-like stemness, shown in panels A-C and Fig S9. In vitro levels were equated to 1 to normalize the graph, and in vivo levels were correspondingly adjusted. Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes between the same cell/signature averages in vitro versus in vivo. ns: difference not significant. Note the clear and strong differences in CD133+ cells.

These unexpected results suggest that the in vitro microenvironment imposes an inappropriate crypt/adenoma/early CC state on advanced and metastatic CC cells. Thus, the pathway and molecular interactions described above in vitro are appropriate of CCs with early, non-metastatic (TNM1,2) character. The data also suggest that the state of advanced and metastatic CCs (TNM3,4) as well as liver metastases, in contrast, is only faithfully maintained in vivo in xenografts, the signatures of which recapitulate those of patient metastatic tumours (Fig 1).

TCF activity is not a strict requirement for the growth of CC cell line-derived tumours in vivo

The general repression of a WNT-TCF crypt/adenoma signature in patient samples (Fig 1) and in xenografts versus in vitro culture (Fig 4) raised the possibility that WNT-TCF signalling might be less central in vivo than suspected from the results of in vitro assays. To probe for the requirement of WNT-TCF activity in CC cells in vivo, we first utilized the two established CC cell lines previously used to demonstrate the key role of TCF function in vitro: Ls174T-dnTCF4dox and DLD1-dnTCF4dox (van de Wetering et al, 2002). Ls174T is a near diploid cell line harbouring activated βCAT whereas DLD1 is a microsatellite unstable cell line with mutant APC. These cells were chosen as they show complementary phenotypes representative of most CCs. They are stable clones and display homogeneous dnTCF4 expression only upon doxycycline (dox) addition. Ls174T-dnTCF4dox cells transplanted in vivo displayed TCF target inhibition to the same low levels as in vitro, all as compared with untreated cell controls demonstrating equal potency and the correct operation of the induction system in vitro and in vivo, but this had no impact on tumour growth (Fig 5A–C): tumours resulting from Ls174T-dnTCF4dox cells or parental Ls174T cells with and without dox treatment showed similar growth curves and tumour appearance (Fig 5A and B). This is remarkable as the same level of inhibition in vitro leads to complete growth arrest (Figs 2A; S3).

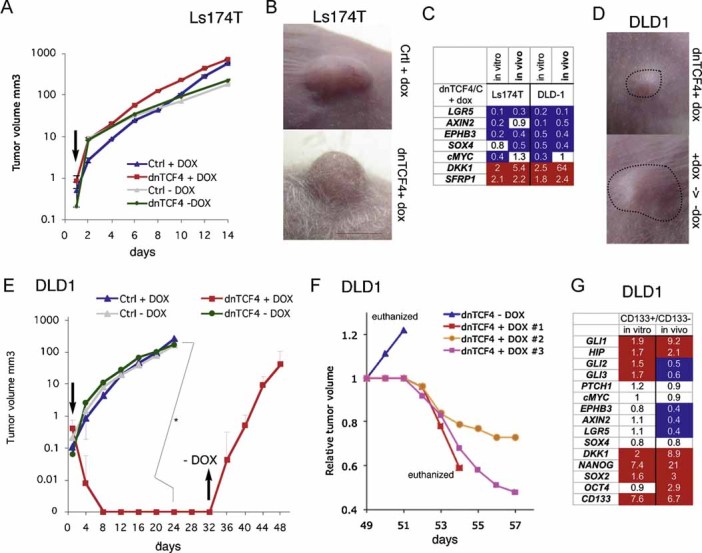

Figure 5. Effects of dox-inducible TCF4 inhibition on CC Ls174T and DLD1 cell line xenograft growth in mice.

A,B,D,E. Xenograft growth curves (A and E) and representative images (B and D) control (Ctrl) and dnTCF4dox (dnTCF4) expressing Ls174T (A and B) or DLD1 (D and E) cells treated with doxycycline (DOX) in vivo. Arrows pointing down in (A and E) denote the time of initiation of dox treatment in vivo after tumour appearance. Arrow pointing up in (E) indicates the time of termination of dox treatment. +dox->-dox in (D lower panel) denotes the growth of the tumour after removal of dox. Tumours in (D) are outlined. n = 8 tumours for each condition. Asterisk denotes significant (p < 0.05) change in Student's t-tests. Error bars represent s.e.m.

C. Gene expression changes induced by dox-inducible dnTCF4 in Ls174T and DLD1 cells in vitro and in vivo shown as the ratios of experimental over control cells without dox, all after normalization as in Fig 1. White boxes denote values within the 0.7–1.4 range. Blue boxes with values equal to or smaller than 0.5. Red boxes with values equal to or greater than 1.5.

F. Growth curves of individual, recurrent DLD1 xenograft tumours from (E) starting at day 49. One tumour was left untreated (blue line), continued to grow aggressively and the animal was euthanized. Three other mice treated again with dox showed a block of tumour growth and reduction of tumour volume. To simplify comparisons, tumour volumes were each equated to 1 at day 49 before restarting dox treatment in order to have all tumours share the same starting point. Actual averaged tumour volumes at day 49 are shown in (E).

G. CD133+/CD133− gene expression ratios in DLD1 cells in vivo versus in vitro, determined by qRT-PCR and after normalization as in Fig 1. As we had found for other CC cells (Varnat et al, 2009), DLD-1 CD133+ cells had enriched CD133 mRNA levels as compared to CD133− cells (6.7-fold in vivo and 7.6-fold in vitro). CD133+ cells were more abundant in vivo than in vitro (16% vs. 5%, respectively). Colours of boxes are as in (C).

DLD1-dnTCF4dox cells treated with dox also repressed TCF targets to the same levels in vitro and in vivo, all compared with untreated cells, but TCF blockade after tumour appearance did inhibit growth, with tumours disappearing within 1 week (Fig 5C–E).

To test if TCF blockade could inhibit all tumour-initiating DLD1-dnTCF4dox cells that could pose the threat of recurrence, dox treatment was terminated after ∼1 month—a time when no tumours were detectable—and the mice were inspected for recurrent tumour growth. Upon cessation of dox treatment, DLD1-dnTCF4dox tumours rapidly grew (Fig 5E; 5/8 cases). Recurrence was not due to escapers since renewed dox treatment inhibited tumour growth anew (Fig 5F). These results prove the effectiveness of dnTCF4 in vivo.

As in the case of Ls174T (Fig 4), DLD1 cells were found to harbour a CD133+ subpopulation with increased levels of HH-GLI and ES-like stemness signature components: GLI1, NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 and DKK1 in vivo versus in vitro (Fig 5G). These cells also showed decreased levels of TCF targets: AXIN2, LGR5 and EPHB3, in vivo versus in vitro, all as compared with CD133− cells (Fig 5G).

Therefore, while DLD1 cells responded as expected to TCF inhibition, Ls174T cells were unaffected, indicating that WNT-TCF is not a strict requirement for CC growth in vivo.

Primary CCs do not require TCF activity in vivo and its blockade can boost tumour growth

To extend and further control these findings we used Ls174T and primary CC36, CC14 and mCC11 cells harbouring dnTCF4ERT2. In this case, dnTCF4 is fused to a TAM-inducible oestrogen receptor module (see above). Moreover, to bypass the potential problems of clonal dnTCF4dox cell lines, we used pooled dnTCF4ERT2 or control (ERT2 alone) stably transfected CC cells. The different cells were then grafted subcutaneously and TAM or corn oil vehicle control given orally after detection of a palpable tumour.

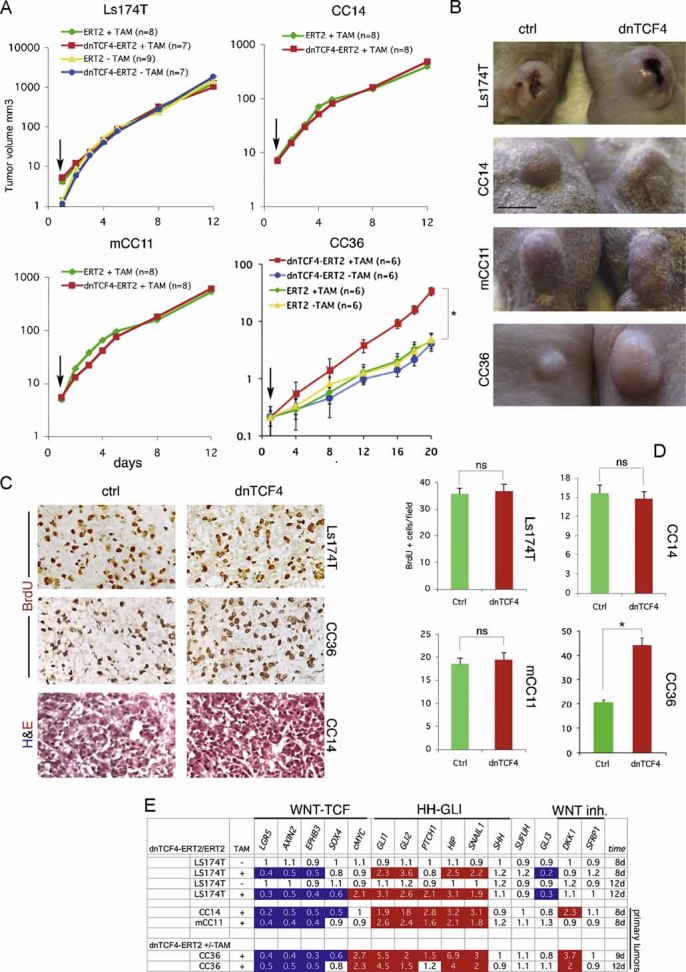

Xenografts of Ls174T-dnTCF4ERT2 cells grew in the presence of TAM equally well than in its absence, perfectly mimicking the results with Ls174T-dnTCF4dox (Figs 5A and B; 6A and B). dnTCF4 activity did not affect tumour growth, cell proliferation, external or histological appearance in non-metastatic CC14 or metastatic mCC11 (Fig 6A–D) while TCF targets were generally repressed in all cells to the same extent as in vitro (Fig 6E). TAM treatment had no effect on Ls174T-ERT2 control cells (Fig 6A).

Figure 6. Effects of TAM-inducible TCF4 blockade in Ls174T and primary human CCs in xenografts in mice.

A. Growth curves of xenografts with Ls174T, CC14, mCC11 or CC36 cells carrying dnTCF4ERT2 or ERT2 alone with (+) or without (−) TAM treatment as indicated. Plots show logarithmic Y-axis scales. Arrows point to the beginning of TAM addition once the tumours were visible. Growth curves are overlapping except for those of CC36. ns: not significant in Student's t-tests. Error bars represent s.e.m.

B. Representative images of xenograft tumours of Ctrl (ERT2, +TAM) or dnTCF4 (dnTCF4ERT2, +TAM) taken at the same time.

C,D. Histological sections of xenografts shown in (B) displaying BrdU incorporation (brown in nuclei in top two rows, C) or morphology after H&E staining (bottom row, C), and quantification of cell proliferation (D). Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests. ns: not significant. Error bars represent s.e.m.

E. RT-qPCR analyses of human CC xenografts harvested 8-12d after continuous treatment with TAM (+) or vehicle (−) similar to those shown in (A and B). The values are ratios of human-specific gene expression levels after normalization between tumours expressing dnTCF4ERT2 over those expressing the control ERT2 part only with or without TAM as indicated. In the absence of induction by TAM the ratios are ∼1. White boxes denote values within the 0.7–1.4 range. Blue boxes with values equal to or smaller than 0.5. Red boxes with values equal to or greater than 1.5.

Scale bar = 5 mm (B), 100 µm (C).

In contrast to Ls174T, CC14 and mCC11 in which TCF blockade had no effect, CC36-dnTCF4ERT2 cells treated with TAM displayed a ∼2-fold increase in BrdU incorporation and an ∼8-fold increase in the volume of the resulting tumour, as compared with untreated cells (Fig 6A–D). Analysis of gene expression in vivo confirmed the repression of TCF targets to the same extent as the other primary CCs and revealed the upregulation of DKK1 and the HH-GLI pathway (Fig 6E). Moreover, it revealed the dissociation of cMYC from TCF activity in vivo (Fig 6E). Primary human CCs therefore do not generally require WNT-TCF activity for growth in mice and, surprisingly, its inhibition can even enhance tumour growth.

CC36 CD133+ cells with cell-autonomous TCF blockade outcompete sibling cells in vivo

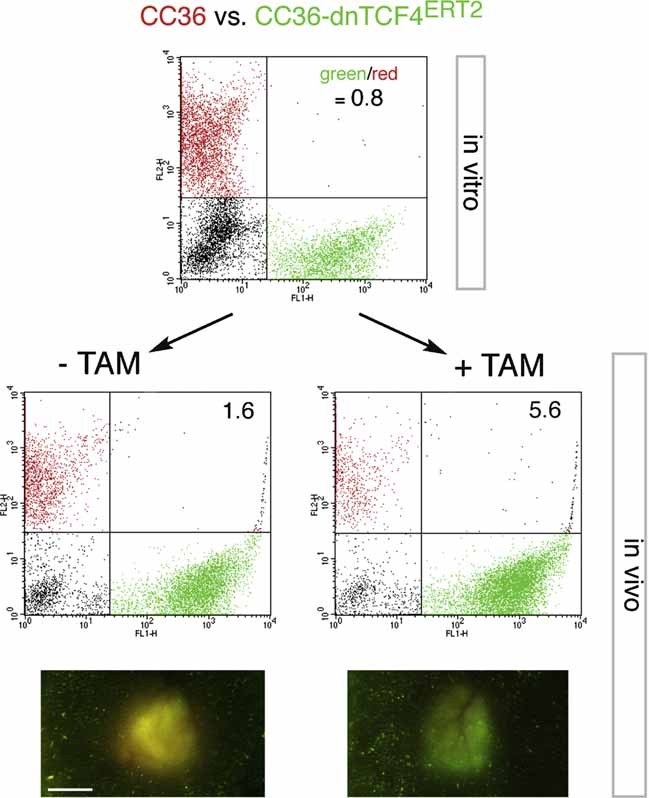

To test if CD133+ stem cells were affected in CC36 responding to TCF blockade and to discern the cell autonomy of this effect, we have used a novel ‘Red/Green’ competition assay that we developed (Varnat et al, 2009; Zbinden et al, 2010). This assay uses a mixed population of fluorescent red (RFP+) and green fluorescent protein (GFP+) transduced tumour cells that can be monitored by in vivo imaging and by FACS analysis after tumour dissociation and MACS sorting for CD133+ cells, thus tracking the behavior of the CD133+ stem cell population.

CC36-dnTCF4ERT2; GFP+ cells tested in competition with wt sibling RFP+ cells in the Red/Green assay showed that TCF inhibition in GFP+ cells through TAM addition (+TAM tumours in Fig 7) lead to an increase in the overall green dnTCF4ERT2; GFP+ population in relation to the control, sibling RFP+ population. This was seen in whole tumour images and in FACS plots analyzing the population sizes of sorted CD133+; GFP+ versus CD133+; RFP+ cells, always in relation to identical tumours not treated with TAM (−TAM tumours; Fig 7). Whereas there were similar populations of CD133+ cells in the +TAM versus −TAM tumours (15% vs. 12%), the CC36-dnTCF4ERT2; GFP+; CD133+ stem cell population increased 3.5-fold upon inhibition of TCF activity, always in relation to the RFP+control populations. This suggests that WNT-TCF activity restricts CC36 stem cell expansion in vivo in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 7. In vivo competition reveals enhancement of the CD133+ CC stem cell population after TCF blockade.

CC36 cells transduced with RFP+ (red) lentivectors, or CC36-dnTCF4ERT2 transduced with GFP+ (green) lentivectors were mixed in similar amounts (FACS green to red ratio of 0.8) in vitro. Untransduced cells were also present (black cells in the FACS plots). This mixture was injected subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice. Their treatment with TAM (+TAM) or corn oil vehicle only (−TAM) once a day for 8 days resulted in a 3.5-fold increase in the green/red ratio in MACS sorted CD133+ cells in the tumours treated with TAM as compared with control tumours (−TAM). The increase of green over red cells in tumours without TAM maybe due to a slight leakiness of the system leading to a small amount of dnTCF4 activity in the absence of TAM. Nevertheless, +TAM tumours were greener than −TAM tumours, which were yellow due to near equivalent green and red cell populations as exemplified in the micrographs in the bottom panels. n = 2 per sample. Average ratios are shown inside the FACS plots. Scale bar = 4 mm.

General enhancement of metastatic growth of CCs by TCF blockade

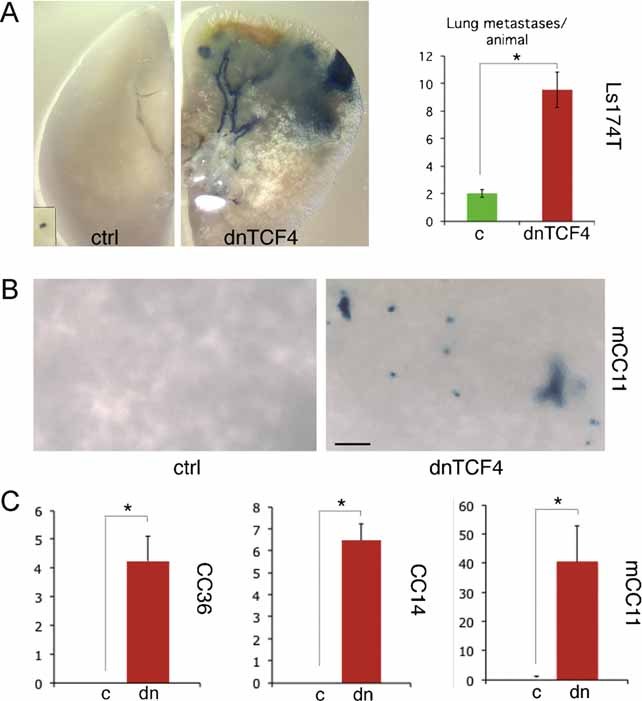

As an additional stringent test in vivo, we analyzed the requirement of TCF activity in metastatic growth, testing also the idea that the coincidence of a repressed WNT-TCF signature and the presence of metastases in patients could be functionally related. Here we have analyzed the growth of lung metastases after injection of CC cells expressing dnTCF4ERT2 into the tail vein of immunocompromised mice. Cells to be injected were transduced with a LacZ-expressing lentivector to be able to detect even single cells in the lungs after X-Gal staining (Stecca et al, 2007). Two weeks after injection, when cells have already left the circulation, one half of the cohort was given corn oil as vehicle and the other received TAM in corn oil. Injected mice were scored for lung metastases 2 months after injection, giving ample time for cells to colonize the target tissues and proliferate.

Vehicle-treated Ls174T-dnTCF4ERT2 cells produced few and small lung metastases as expected (Varnat et al, 2009) (Fig 8A), whereas, strikingly, Ls174T-dnTCF4ERT2 treated with TAM yielded a ∼5-fold increase in the number of metastatic lesions, which were often larger (Fig 8A). More extreme results were obtained with metastatic mCC11 cells, yielding a 40-fold increase in the number of metastases after TCF blockade (Fig 8B and C). Importantly, CC36 and CC14 cells, derived from localized CCs in the intestinal wall, yielded no detectable metastases after treatment with vehicle, but became metastatic upon TCF blockade after TAM treatment (Fig 8C).

Figure 8. Enhanced metastatic behavior by blockade of TCF activity in vivo.

A,B. Images of dissected lungs after X-Gal staining (blue) showing metastatic growth of Ls174T-LacZ+-dnTCF4ERT2 (A) or mCC11-LacZ+-dnTCF4ERT2 (B) cells after systemic treatment with TAM (dnTCF4) or corn oil vehicle as control (ctrl).

C. Quantification of lung metastases per animal in LacZ+-dnTCF4ERT2 injected animals treated with TAM as compared with those identical injected but treated only with vehicle (corn oil). Results for CC36, CC14 and mCC11 are shown. Asterisks denote significant (p < 0.05) changes in Student's t-tests. Error bars represent s.e.m.

Scale bar = 1.5 mm (A), 0.1 mm (A inset), 150 µm (B).

The increased tumour growth in CC36 and the generalized increase in metastatic growth by TCF blockade suggest that human CCs may repress aspects of the crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF programme to become metastatic.

DISCUSSION

The metastatic transition of human CCs involves a WNT-TCF to HH-GLI predominant pathway switch

Here we describe a novel molecular switch that characterizes the metastatic transition of human CCs, which we have discovered in fresh tumour samples from patients. This transition, which is most prominent in the CD133+ epithelial tumour stem cell population, involves the repression of archetypal components of the crypt/adenoma/early carcinoma WNT-TCF programme (e.g. van de Wetering et al, 2002; van der Flier et al, 2007; Yochum et al, 2007; this work), and perfectly coincides with the upregulation of HH-GLI signalling we have recently discovered (Varnat et al, 2009). This transition also appears to involve the inhibition of any ligand-driven WNT signalling as suggested by the upregulation of the WNT-LRP-FRZ signalling inhibitors DKK1 and SFRP1 in metastatic CCs and liver metastases. Furthermore, a change in the character of metastatic versus non-metastatic CCs is suggested by the increase in components of the HH-GLI-regulated ES-like stemness signature in CD133+ and CD133− cells. Since the signatures of both CD133+ and CD133− cells are recapitulated in xenografts with purified human CC epithelial cells, we interpret them as readouts of the state of CC cells in general and those in CD133+ cells as readouts of CC stem cells. Taken together, the gene expression signatures in CD133+ and CD133− cells of CCs of different stages suggest that CCs repress early non-metastatic, crypt/adenoma-like WNT-TCF activity and enhance HH-GLI function in their stem cells to become metastatic.

Our findings are consistent with the downregulation of a cohort of crypt/adenoma WNT-TCF targets in whole unsorted CCs (van der Flier et al, 2007). However, since a distinct subset of targets was still detected in CCs (van der Flier et al, 2007), aspects of non-crypt/adenoma WNT signalling could remain active in advanced CCs. Nevertheless, it is not known if these targets are expressed in CD133+ cells or if the CCs used were early CCs (TNM1,2), which resemble adenomas in their WNT-TCF signatures, or late CCs (TNM3,4), which do not.

The existence of the molecular metastatic transition that we describe herein is surprising given the heterogeneity of the randomly obtained CCs, of the cell populations used, and of the medical histories of the patients. While future studies with larger cohorts will address further details of this transition, such as the possible correlation with CD26 expression in a subpopulation of CD133+ cells (Pang et al, 2010), the presence of the transition in all samples analyzed strongly suggests that this represents a general phenomenon. The presence of a metastatic transition is also surprising given the usual varied landscape of genetic lesions in the different tumours, and the likely varied timing required by each individual tumour to become metastatic. The consistency of the transition we detect thus suggests that it is functionally relevant.

In vitro culture imposes an early CC identity, enhancing WNT-TCF and decreasing HH-GLI signature levels

We find that the microenvironment in which CC cells grow determines WNT-TCF and HH-GLI pathway levels and use. The appreciation of this surprising finding is critical to understand why the previously untested but widely accepted extension of the WNT-TCF addiction of adenomas to metastatic CC and liver metastases is not appropriate:

The character and signatures of early, non-metastatic (TNM1,2) CCs—low HH-GLI and high WNT-TCF is imposed on advanced metastatic CC and CC liver metastases cells when grown in vitro. Molecular mechanisms of CC cell proliferation and survival elucidated in vitro, such as the boosting of GLI1 activity by CC oncogenes and the GLI1-cMYC regulatory loop we describe, thus relate to TNM1,2 tumours and pertain to their progression.

In contrast, the character of advanced and metastatic (TNM3,4) CCs is only faithfully maintained in vivo in xenografts, the profiles of which mimic those of advanced, metastatic CCs and liver metastases from patients, where HH-GLI is high and WNT-TCF (and cMYC) is low. Loss of WNT-TCF addiction in vivo is thus pertinent to metastatic CCs and liver metastases.

Neither in vitro culture nor xenografts have been found in retrospect to be perfect predictors of tumour behavior in patients. However, our data suggest that it is inappropriate to test for the function of WNT-TCF that metastatic CCs and metastases may have in vivo using in vitro culture. Instead, our results suggest that in vivo analyses in mice more closely recapitulate the situation in patient tumours for HH-GLI and WNT-TCF signalling. Consistently, a study published while this paper was in revision suggests effects of secreted factors on WNT-TCF activity in CCs (Vermeulen et al, 2010). It also suggests that CC stem cells harbour high WNT-TCF activity but, unfortunately, their key transplantation tests relied on cells of unspecified TNM stage selected as high TCF-binding-site-GFP expressors in vitro, making it thus unclear what was actually being measured since we find that high WNT-TCF activity in CC cells grown in vitro can be artifactual.

Metastatic CCs and liver metastases generally require WNT-TCF in vitro but not in vivo

In vitro, and thus in CCs with non-metastatic character (proper of the stage or imposed by the in vitro microenvironment), we find that both WNT-TCF and HH-GLI are ubiquitously required for CC cell proliferation and survival, in full agreement with previous work (e.g. van de Wetering et al, 2002; Varnat et al, 2009).

Such requirement of WNT-TCF in vitro in all CCs—independent of their original identity have led to the accepted general idea that advanced and metastatic CCs maintain and require a crypt/adenoma/early CC WNT-TCF programme (e.g. Chen et al, 2009; Huang et al, 2009; van de Wetering et al, 2002).

In vivo, we show that WNT-TCF activity is not a general requisite for CC growth using two different ways to activate TCF blockade. Moreover, we provide evidence to support the idea that endogenous WNT-TCF activity can actually antagonize both tumour growth and, critically, metastatic growth. These findings are against all expectations but, importantly, they do not contradict or deny any previous experimental result. The in vivo requirement of TCF activity in advanced, metastatic CCs had just been assumed but never actually tested under conditions that preserve their identity.

We find that only one cell line tested in vivo requires TCF activity for tumour growth, but, importantly, none of the primary CCs tested do. Moreover, inhibition of TCF activity enhances metastatic growth in all cases analyzed. While future studies with additional primary CCs will address the penetrance of these phenotypes and possible correlations with other parameters (e.g. DLD1, but not Ls174T, cells are microsatellite unstable), our data already show that TCF function is not a general requirement in advanced CCs in vivo, as opposed to in vitro (this work; van de Wetering et al, 2002). Moreover, they suggest that repression of WNT-TCF activity, as seen in metastatic patient samples, promotes metastatic behavior.

HH-GLI and WNT-TCF interactions

In this study we have also explored possible interactions of HH-GLI with WNT-TCF as well as with key oncogenic and tumour suppressive inputs in CC in an attempt to shed light on the mechanisms that may drive the progression of early TNM1,2 CCs towards metastatic states.

The upregulation of HH-GLI1 and downregulation of early crypt/adenoma-like CC WNT-TCF signatures at the metastatic transition that we describe here appear to be linked: the low WNT-TCF/high HH-GLI profile of metastatic CCs is reproduced through the downregulation of the TCF signature by experimentally enhanced HH-GLI. Conversely, HH-GLI is enhanced by the experimental TCF blockade.

In CCs with non-metastatic character and in metastatic CCs grown in vitro in which a non-metastatic state is imposed by the microenvironment, HH-GLI and WNT-TCF may interact at multiple levels: in a positive manner through the common regulation of cMYC and through an antagonistic manner by effects on GLI3. Since we find that WNT-TCF regulates GLI3 transcription, its repressor function (GLI3R) might mediate the restrictive activity of WNT-TCF on GLI1. This situation would then be abolished by enhanced HH-GLI signalling, which represses GLI3 and WNT-TCF signature levels.

Conversely, we provide evidence that βCAT, which is required for CC growth (Roh et al, 2001), can negatively regulate GLI3R and positively regulate GLI1 exogenous activities independent of TCF in CCs generally and in their CD133+ stem cell populations. These results are consistent with previous data on the binding of βCAT to GLI3R (Maeda et al, 2006; Ulloa et al, 2007) and possibly to GLI1 (Liao et al, 2009) in other cells. Taken together, the data suggest an interactive balance in non-metastatic CCs between HH-GLI and WNT-TCF, with cross-regulation at different levels (Fig 2H).

GLI1 activity is boosted by oncogenes and loss of tumour suppressors characteristic of CC progression

What then drives the high-to-low WNT-TCF and low-to-high HH-GLI pathway level switch, most notably but not exclusively in CD133+ CC stem cells, at the metastatic transition? In addition to the boosting of GLI1 activity by βCAT (see above), we show that GLI1 transcriptional activity can also be enhanced by cMYC, oncogenic KRAS-MEK/AKT and loss of PTEN and p53. These positive effects are detected in both whole and in CD133+ CC cell populations, supporting the notion that regulation of GLI1 in stem cells is critical. GLI1 could similarly be enhanced indirectly through the upregulation of βCAT by oncogenic KRAS and loss of p53 (Janssen et al, 2006; Sadot et al, 2001).

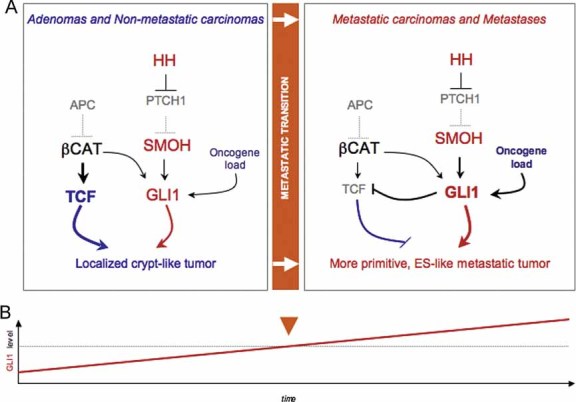

While the mechanisms of GLI1 regulation are only beginning to be understood and are likely to be context-dependent (Lauth et al, 2010; Stecca & Ruiz i Altaba, 2010; Zbinden et al, 2010), the end result is the progressive accumulation of events that boost GLI1 activity over time in an irreversible manner. These findings lend support to and extend a model (Fig 9; Ruiz i Altaba et al, 2002, 2007) in which the boosting of GLI1 above a critical threshold by the accumulating oncogenic load drives the metastatic transition's molecular switch, in part by driving epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (Varnat et al, 2009), crypt-like WNT-TCF repression and enhancement of the ES-like signature. After the metastatic switch takes place, some of the regulatory interactions present in early non-metastatic tumours will cease, such as the positive feedback regulation between GLI1 and cMYC.

Figure 9. Model of molecular mechanisms underlying the metastatic transition and the proposed evolution of cancer stem cells by reprogramming.

- Diagram of the changes in pathway use in non-metastatic versus metastatic CCs, highlighting the metastatic transition and the recapitulation of non-metastatic CCs by in vitro conditions and of metastatic CCs by in vivo xenograft conditions. WNT-TCF and HH-GLI interactions are highlighted.

- Model for the proposed role of GLI1 driving the metastatic transition when its activity levels, enhanced by multiple oncogene and loss of tumour suppressor events (the oncogene load), reach a threshold. This model recapitulates morphogenetic gradient interpretation resulting in distinct cell fates during development. Cancer stem cell reprogramming is proposed to be GLI1 driven at the metastatic transition.

Tumour reprogramming and the evolution of cancer stem cells towards advanced and metastatic states

As CCs develop metastases, the levels of two components of an HH-GLI-dependent ES-like signature, KLF4 and SOX2, increase in both CD133+ and CD133− cells. Whereas the consequence of this is unclear we already know that several types of advanced human tumours display an ES-like signature, as first discovered in gliomas (Clement et al, 2007) and later in other cancers (Ben-Porath et al, 2008) and that at least SOX2 (Gangemi et al, 2009) and NANOG (Zbinden et al, 2010) are essential for glioblastoma stem cells and tumorigenicity in vivo. Thus, one possibility is that CC stem cells with enhanced ES-like signatures become more primitive.

Interestingly, the ES-like stemness genes NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 (i) are present and/or upregulated in advanced CCs (this work), (ii) are all induced by and require HH-GLI1 activity in CCs and other cancers (Clement et al, 2007; Stecca & Ruiz i Altaba, 2009; Zbinden et al, 2010; this work) and (iii) form a cohort which mimics that involved in cell reprogramming (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al, 2007). We therefore suggest that cancer stem cells evolve from organ specific (crypt-like for CCs) to more primitive (ES-like) and metastatic states, and that this is through GLI1-driven epigenetic events akin to reprogramming once a threshold level of GLI1 activity is achieved (Fig 9).

Therapeutic implications

Major efforts are underway to develop TCF inhibitors for CC therapy (e.g. Chen et al, 2009; Huang et al, 2009; Lepourcelet et al, 2004; reviewed in Barker & Clevers, 2006), in which in vitro assays have guided the assessment of CC growth inhibition efficacy (e.g. Huang et al, 2009; van de Wetering et al, 2002). In contrast, our present and recent (Varnat et al, 2009) data support the blockade of HH-GLI but not of WNT-TCF as a therapeutic strategy for so far incurable metastatic CCs. We suggest blocking of GLI1 and tumor deprogramming (blocking the proposed tumour reprogramming) as anti-metastatic strategies. Moreover, while WNT-TCF blockade may be effective for early adenomas and non-metastatic CCs, it could be highly counterproductive in advanced and metastatic disease. Care should thus be taken when administering WNT-TCF pathway inhibitors, such as aspirin (Dihlmann et al, 2003; Nath et al, 2003), to patients with localized CCs or to populations at risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human CC specimens and cells

Early passage primary human CC14 (TNM4), CC36 (TNM3) and mCC11 (liver metastasis) cells were obtained under approved ethical protocols and patient consent from the University of Geneva Hospitals, are described in Varnat et al (2009), and were grown in 10% FBS. βCAT mutant Ls174T-dnTCFdox and APC mutant DLD1-dnTCFdox were grown under standard conditions (van de Wetering et al, 2002) and were kind gifts from H. Clevers (Utrecht) and J. Behrens (Erlangen). Induction in vitro was with 5 µg/ml dox. Ls174T-dnTCF4ERT2, CC14-dnTCF4ERT2, mCC11-dnTCF4ERT2 and CC36-dnTCF4ERT2 were pools of stably transfected cells. Induction in vitro was with 1 µM 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Collagen assays were performed in 24-well plates by placing a 5 µl drop containing 1.5 × 103 cells mixed with collagen (diluted in medium to 2 mg/ml of rat Collagen I, GIBCO) on top of a collagen cushion and covering this with a second collagen layer. Cells were fed daily with Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium nutrient mixture F-12 Ham (Sigma), 10% FBS plus antibiotics and antimycotics and analyzed 1–2 weeks after seeding.

The paper explained

PROBLEM:

Colorectal cancers are highly prevalent worldwide with over 1 million new cases yearly and despite numerous efforts the cure rates from metastatic disease are below 5%. Over 90% of human CCs have been reporter to harbour an active WNT-TCF pathway, CC cells in vitro require WNT-TCF activity and mouse intestinal tumours develop through deregulated Wnt-Tcf signalling. Together, these results have spurred major efforts to develop WNT-TCF inhibitors to treat metastatic disease, which remains a major unmet medical need. In addition to WNT-TCF, HH-GLI is also required for CC growth and stem cell expansion. However, how these pathways interact in CC cells is not known.

RESULTS:

We have discovered coincident high-to-low WNT-TCF and low-to-high HH-GLI transitions in patient CCs, most strikingly in their CD133+ stem cells, that mark the development of metastases. This metastatic transition is recapitulated in advanced CCs grown in vitro, in which a high WNT-TCF non-metastatic state is imposed, versus in vivo in xenografts, which faithfully mimic advanced tumours in patients. Consistently, we find that blockade of TCF activity generally inhibits CC growth in vitro, but not in vivo, and that TCF blockade in vivo enhances CC metastases. Analyses of interactions of GLI1 with WNT-TCF, and with CC oncogenes and tumour suppressors, allow us to propose a model in which it is the oncogene- and tumour-suppressor-loss-driven boosting of GLI1 above a threshold during CC progression that drives a pathway switch, the loss of crypt-like and gain of more ES-like primitive states, and the development of metastases.

IMPACT:

We identify a novel molecular switch at the transition of CCs from non-metastatic to metastatic, with an inverse change in the levels of expression of the key CC pathways WNT-TCF and HH-GLI. The metastatic transition may involve GLI1-driven reprogramming-like events in which tumour cells loose part of their original identity to become more primitive and ES-like. Since we find that human advanced, metastatic CCs and liver metastases are not WNT-TCF addicted, whereas we previously showed that these CCs are HH-GLI-dependent, treatments for metastatic disease should therefore block HH-GLI1 but not WNT-TCF activities. Interference with WNT-TCF could in fact be detrimental by promoting metastases.

Immunocytochemistry

Cell proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation for 48 h followed by staining with anti-BrdU antibodies (BD Biosciences) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or RITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Labeled cells were imaged with a Zeiss Axiocam optical microscope.

Plasmids, lentivectors, CD133+ selection, transfections, colony assays and PCR

GLI plasmids were as described (Ruiz i Altaba, 1999). βcateninN′Δ45 was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cloned and NotI/BamHI inserted into the pFLAG-CMV2 vector (Sigma). dnTCF4ERT2 and ERT2 constructs were kind gifts from E. Batlle and G. Whisell (Barcelona). KRASV12G was a kind gift of M. Phillips (New York). Oncogenic MEK1 and AKT1 were as in (Stecca et al, 2007). cMYC and dnMYC (OMOMYC) were kind gifts of A. Trumpp (Heidelberg) and S. Nasi (Rome) (Soucek et al, 2002), respectively. Lentivectors and CD133+ MACS selection were as in (Varnat et al, 2009). 106 of the total or CD133+ selected cell populations of CC cells were mixed with 5 µg of total deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and transfected with a Nucleofector (Amaxa). After 16 h, transfection efficiency was 70–90% and cells were either collected in 500 µl Trizol (Gibco) for RNA extraction or analyzed for colony formation in 35 mm dishes. After 3 weeks, cresyl violet-stained colonies were counted. RT-qPCR reaction conditions were as in (Varnat et al, 2009).

Mouse xenografts, metastatic and ‘red/green’ competition assays

Six- to 8-week-old female NMRI mice received each two injections of 105–106 human CC cells each on their backs. As soon as the tumour was palpable (1–2 mm), TAM (2 mg/day by oral dosing) or dox (2 g/L in 5% sucrose in the drinking water plus one IP injection of 500 mg every 2 days) was given and tumour size measured periodically with a caliper. Mice were sacrificed before the tumours approached the legal size limit. For metastatic assays, 106 Ls174T-dnTC4ERT2 cells were injected into the tail vein and mice given TAM or saline for 1.5 months starting 2 weeks after injection. Lungs were stained in toto with X-Gal (Stecca et al, 2007; Varnat et al, 2009). Red/green competition assays were performed as described in Varnat et al (2009) and Zbinden et al (2010).

Luciferase reporter assays

GLI (GBS) and mutant (mGBS), and TCF (TOP) and mutant (FOP) binding site-luciferase reporter assays were performed as described with renilla control reporters (Promega). Transfections (Amaxa) were analyzed after 16–24 h and had equal amounts of DNA unless otherwise stated.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Clevers, M. Scott, A. Duquet, E. Fearon, N. Dahmane, C. Mas, A. Carleton, A. Melotti, A. Lorente-Trigos and all Ruiz i Altaba lab members for discussion and/or comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to E. Batlle and G. Whisell (Barcelona) for dnTCF4ERT2 and ERT2 constructs, H. Clevers (Utrecht) and J. Behrens (Berlin) for cells and S. Nasi (Rome), A. Trumpp (Heidelberg) and M. Phillips (New York) for constructs. ISC is a recipient of a Human Frontiers Science Project Long Term Fellowship. This work was supported by institutional funds from the Département d'Instruction Publique of Geneva and by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Cancer League and Jeantet and Swissbridge Foundation to ARA.

Supporting information is available at EMBO Molecular Medicine online.

Conflict of interest: ARA is a consultant for and holds stock in Phistem.

Author contributions

ARA, FV, ISC and MM designed experiments. ISC performed the collagen assays, MM the metastases assays and FV the rest. PG provided tumour samples and medical data. ARA wrote the paper with input from FV and ISC.

Supplementary material

Detailed facts of importance to specialist readers are published as ”Supporting Information”. Such documents are peer-reviewed, but not copy-edited or typeset. They are made available as submitted by the authors.

References

- Agren M, Kogerman P, Kleman MI, Wessling M, Toftgård R. Expression of the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene is regulated by alternative promoters and a single functional Gli-binding site. Gene. 2004;330:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyoshi T, Nakamura M, Koga K, Nakashima H, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M, Katano M. Gli1, downregulated in colorectal cancers, inhibits proliferation of colon cancer cells involving Wnt signalling activation. Gut. 2006;55:991–999. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Medina R, Cayuso J, Okubo T, Takada S, Martí E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135:237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura S, Matsunaga A, Kitamura T, Aoki K, Aoki M, Taketo MM. Reduced level of smoothened suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis by down-regulation of Wnt signaling. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:629–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Clevers H. Mining the Wnt pathway for cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:997–1014. doi: 10.1038/nrd2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement V, Sanchez P, de Tribolet N, Radovanovic I, Ruiz i Altaba A. HEDGEHOG-GLI1 signaling regulates human glioma growth, cancer stem cell self-renewal, and tumorigenicity. Curr Biol. 2007;17:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dihlmann S, Klein S, Doeberitz Mv MK. Reduction of beta-catenin/T-cell transcription factor signaling by aspirin and indomethacin is caused by an increased stabilization of phosphorylated beta-catenin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:509–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi RM, Griffero F, Marubbi D, Perera M, Capra MC, Malatesta P, Ravetti GL, Zona GL, Daga A, Corte G. SOX2 silencing in glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells causes stop of proliferation and loss of tumorigenicity. Stem Cells. 2009;27:40–48. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sancho JM, Aguilera O, García JM, Pendás-Franco N, Peña C, Cal S, García de Herreros A, Bonilla F, Muñoz A. The Wnt antagonist DICKKOPF-1 gene is a downstream target of beta-catenin/TCF and is downregulated in human colon cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:1098–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppler S, Kavanagh CL. Wnt signalling: variety at the core. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:385–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, Charlat O, Wiellette E, Zhang Y, Wiessner S, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen KP, Alberici P, Fsihi H, Gaspar C, Breukel C, Franken P, Rosty C, Abal M, El Marjou F, Smits R, et al. APC and oncogenic KRAS are synergistic in enhancing Wnt signaling in intestinal tumor formation and progression. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1096–1109. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauth M, Bergström A, Shimokawa T, Tostar U, Jin Q, Fendrich V, Guerra C, Barbacid M, Toftgård R. DYRK1B-dependent autocrine-to-paracrine shift of Hedgehog signaling by mutant RAS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:718–725. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepourcelet M, Chen YN, France DS, Wang H, Crews P, Petersen F, Bruseo C, Wood AW, Shivdasani RA. Small-molecule antagonists of the oncogenic Tcf/beta-catenin protein complex. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JY, Kolligs FT, Wu R, Zhai Y, Kuick R, Hanash S, Cho KR, Fearon ER. Activation of AXIN2 expression by beta-catenin-T cell factor. A feedback repressor pathway regulating Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;14:21657–21665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X, Siu MK, Au CW, Chan QK, Chan HY, Wong ES, Ip PP, Ngan HY, Cheung AN. Aberrant activation of hedgehog signaling pathway contributes to endometrial carcinogenesis through beta-catenin. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:839–847. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda O, Kondo M, Fujita T, Usami N, Fukui T, Shimokata K, Ando T, Goto H, Sekido Y. Enhancement of GLI1-transcriptional activity by beta-catenin in human cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2006;16:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath N, Kashfi K, Chen J, Rigas B. Nitric oxide-donating aspirin inhibits beta-catenin/T cell factor (TCF) signaling in SW480 colon cancer cells by disrupting the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12584–12589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134840100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niida A, Hiroko T, Kasai M, Furukawa Y, Nakamura Y, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Akiyama T. DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the beta-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:8520–8526. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. Human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang R, Law WL, Chu AC, Poon JT, Lam CS, Chow AK, Ng L, Cheung LW, Lan XR, Lan HY, et al. A subpopulation of CD26+ cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity in human colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh H, Green DW, Boswell CB, Pippin JA, Drebin JA. Suppression of beta-catenin inhibits the neoplastic growth of APC-mutant colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6563–6568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli proteins encode context-dependent positive and negative functions: implications for development and disease. Development. 1999;126:3205–3216. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A. Hedgehog-Gli Signaling in Human Disease. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience, Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]