Abstract

Introduction

S8949 demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) for palliative debulking nephrectomy in interferon-treated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). We updated the primary analysis of S8949, now with a median follow-up time of 9 years, and explored clinical predictors of OS.

Methods

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of clinical variables potentially influencing survival, including early progression within 90 days (PD) and performance status (PS), among others.

Results

Two hundred forty six patients with advanced or metastatic RCC were randomized to interferon with or without nephrectomy. Of 241 eligible patients, median age was 59 years, 167 (69%) were male and 125 (52%) had PS 1. Patients randomized to nephrectomy had improved OS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.74, 95% CI 0.57–0.96 p=0.022), confirming the original report. Univariate analysis showed PS=1 (p<0.0001), hemoglobin below the median (p=0.015), and early PD within 90 days (p<0.0001) as poor prognostic factors. Multivariate analysis showed PS 1 vs. 0 (HR 1.95, p<0.0001), high alkaline phosphatase (HR 1.5, p=0.002) and lung metastases only (HR 0.73, p=0.028) as OS predictors. There was no evidence of an interaction of PS, hemoglobin or lung metastases with nephrectomy (all P>0.20). In a patient subset surviving at least 90 days post-randomization, early PD was also a significant predictor of survival in a multivariate model (HR 2.1, p<0.0001) as was PS (HR 1.7, p=0.0006).

Conclusions

Nephrectomy prolongs long-term OS in this updated analysis, supporting its role as standard therapy for advanced RCC patients. The benefit from nephrectomy was seen across all pre-specified patient subsets. Early PD (within 90 days) and PS were strong predictors of OS. These results support current efforts to identify biomarkers of RCC treatment resistance and early PD to facilitate rational patient selection for systemic therapy.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a highly heterogeneous malignancy, exhibiting marked variability in disease behavior, histology and molecular biology.1 Localized RCC generally carries a good prognosis while extensive disease is essentially incurable. Although stage is perhaps the most important prognostic factor, many other factors such as tumor grade, performance status, and proliferation index have been reported to influence prognosis.

Some have attempted to evaluate clinical prognostic and predictive factors to aid in treatment selection and clinical trial design.2, 3, 4, 5 Independent prognostic factors found on multivariate analysis in various studies include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytosis, high lactate dehydrogenase, low serum hemoglobin, high serum calcium, and time from initial diagnosis to immunotherapy of less than 1 year.6, 7, 8 In addition, some molecular tumor markers have been suggested to provide additional prognostic information.9, 10 Models including these markers promise to provide more accurate prognostic data to physicians, allowing for more appropriate treatment planning and patient counseling.

S8949 was the first randomized phase III trial to show benefit for palliative debulking nephrectomy in patients with advanced RCC.11 This trial provides yet another rich and mature database in which to evaluate prognostic or predictive clinical biomarkers for RCC. S8949 enrolled 241 patients with histologically confirmed RCC and performance status 0–1 without prior systemic therapy, randomizing these patients to interferon therapy alone or debulking nephrectomy followed by interferon. Pre-specified stratification factors included performance status (1 versus 0), lung metastases only (yes versus no) and the presence or absence of at least one measurable metastatic lesion that was not to be resected. As originally reported in 2001, patients randomized to the nephrectomy arm enjoyed a significant survival benefit with a median survival tine of 11 months (as compared to 8 months in the control arm), with a p-value of 0.05.11

We hypothesized that clinical variables collected as part of S8949 would provide prognostic and predictive information for patients with advanced RCC. Our objectives were to evaluate patient subsets with regard to these variables to see if any particular subset benefited more or less from nephrectomy (that is, predictive factors) and to assess these variables for potential prognostic significance with regard to their survival.

Patients and Methods

S8949 data were updated in the present analysis – now with a median follow up time of 9 years. Since the original publication,11 there have been 18 additional deaths (5 on the interferon arm and 13 on the nephrectomy arm). Clinical variables were included in univariate and multivariate analyses to assess for associations with overall survival. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In addition, these variables were evaluated in two Cox proportional hazard models. In the first model, all variables except progression within 90 days were assessed. Survival in this model was defined as starting from study registration to date of death due to any cause. Patients who are still alive were censored at their last contact date. In the second model, all variables -including progression within 90 days - were evaluated. Landmark analysis of survival in this model was defined starting at 90 days post-registration, and only patients surviving at least 90 days are included in the analysis. All p-values reported are two-sided.

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical variables from S8949 are summarized in Table 1. Thyroid stimulating hormone and calcium levels were collected only after the initiation of the study and therefore were not available for all patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Variables in SWOG 8949

| Variable | Number of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| N=241 | ||

| Randomized to Nephrectomy | 120 | 49.8 |

| Male sex | 167 | 69.3 |

| Progression within 90 days | 63 | 32.5 |

| Variable | Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 59 (28 – 86) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.4 (6.8 – 18) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 108 (30 – 113) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.4 – 9.0) |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 5.6 (4.4 – 15.4) |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (mIU/L) | 1.9 (0.01 – 21) |

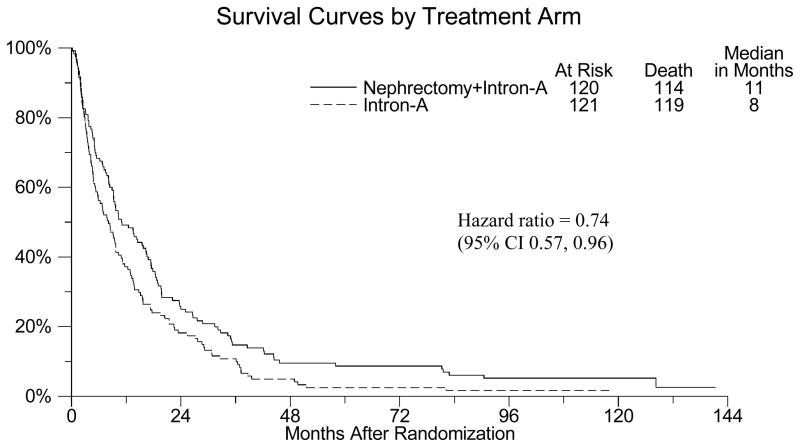

Figure 1 shows the updated Kaplan-Meier survival curves for S8949. Median survival time for patients randomized to nephrectomy plus interferon was 11 months while those randomized to interferon alone was 8 months. The p-value for this comparison was 0.021. The hazard ratio of 0.74 indicates a 26% reduction in death in favor of nephrectomy during the course of the study.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for S8949

The effect of nephrectomy on survival for each of the predefined stratification factors are summarized in Table 2. Nephrectomy benefited patients regardless of stratum, indicated by hazard ratios for survival less than 1 in all patient strata, mirroring the overall results for the entire cohort. The interaction of nephrectomy with each stratification factor was not statistically significant (all p>0.30), providing no evidence of a differential benefit of nephrectomy for any subgroup.

Table 2.

Effect of Nephrectomy on Survival by Subsets Defined by Stratification Factors

| Stratification Factor | Level of Stratification Factor | N (%) | Nephrectomy + IFN vs. IFN survival hazard ratio (95% CI) | Stratification Factor by Nephrectomy Interaction p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Status | 0 | 116 (48%) | 0.76 (0.52, 1.11) | P=0.76 |

| 1 | 125 (52%) | 0.85 (0.59, 1.22) | ||

| Metastastic Sites | Lung Only | 81 (34%) | 0.71(0.45, 1.11) | P=0.57 |

| Other sites | 160 (66%) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.03) | ||

| Disease Status | Measurable | 189 (78%) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.06) | P=0.31 |

| Evaluable | 52 (22%) | 0.52 (0.28, 0.95) |

Abbreviations: IFN – interferon; CI – confidence interval

The effect of clinical variables on survival was assessed in univariate proportional hazards models. These results are summarized in Table 3. Performance status of 1, presence of more than lung metastases, alkaline phosphatase above the median, and hemoglobin below the median were significantly associated with worse survival (all p< 0.051).

Table 3.

Univariate Proportional Hazards Analyses of Survival

| Variable (not adjusted for other factors) | Sample size for each model | Survival Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Status: 1 vs. 0 | 241 | 1.91 (1.47, 2.49) | <0.0001 |

| Lung Metastases: Yes vs. No | 241 | 0.76 (0.58, 1.00) | 0.051 |

| Male vs. Female | 241 | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | 0.49 |

| Measurable vs. Evaluable Disease | 241 | 1.12 (0.82, 1.52) | 0.49 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase+: | 238 | 1.42 (1.10, 1.85) | 0.008 |

| Calcium+: | 65 | 1.18 (0.71, 1.95) | 0.53 |

| Hemoglobin+: | 241 | 0.73 (0.56, 0.94) | 0.015 |

| TSH+: | 188 | 1.00 (0.75, 1.34) | 0.99 |

| Age+: | 241 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | 0.54 |

| Weight loss+: # | 198 | 1.26 (0.95, 1.68) | 0.11 |

| BUN+: | 231 | 1.01 (0.77, 1.31) | 0.96 |

| Creatinine+: | 236 | 0.94 (0.72, 1.22) | 0.64 |

| Progression within first 90 days*: Yes vs. No | 194 | 2.04 (1.50, 2.79) | <0.0001 |

Patient must be alive 90 days post-randomization to be included in the analysis

Estimated weight loss in Kg over 6 months

Hazard ratios compare values above vs. below the median

The first of two multivariate models is shown in Table 4. When assessing risk factors at study entry (that is, when early progression within 90 days was excluded), the following clinical variable were found to be independent predictors of worse survival: performance status, presence of more than lung metastases, not randomized to nephrectomy, alkaline phosphatase level above the median, and hemoglobin level below the median.

Table 4.

Multivariate Proportional Hazards Model Excluding Early Progression, with Survival Defined Starting at Study Registration (n=238)

| Variable (adjusted for other factors in the model) | Survival Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Status 1 vs. 0 | 1.95 (1.49, 2.54) | <0.0001 |

| Lung Metastases: Yes vs. No | 0.73 (0.55, 0.97) | 0.028 |

| Randomized to Nephrectomy | 0.78 (0.60, 1.02) | 0.072 |

| Alkaline Phos: above vs. below median | 1.53 (1.17, 2.00) | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin: above vs. below median | 0.76 (0.59, 1.00) | 0.047 |

In the second multivariate model, a Landmark analysis of the effect of clinical variables on survival starting 90 days post-randomization was performed and is summarized in Table 5. In this model, only performance status and progression by 90 days were shown to be significantly associated with survival. Patients with performance status of 1 had a hazard ratio for survival of 1.7, with a corresponding p-value of 0.0006. Early progression had an even higher hazard ratio of 2.1, representing a two fold increase in the risk of death, with a corresponding p-value of <0.0001.

Table 5.

Multivariate Proportional Hazards Model Including Early Progression, with Survival Defined as Starting at 90 Days Post-Registration (n= 191)

| Variable (adjusted for other factors in the model) | Survival Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Status 1 vs. 0 | 1.70 (1.26, 2.31) | 0.0006 |

| Lung Mets: Yes vs. No | 0.81 (0.59, 1.11) | 0.19 |

| Randomized to Nephrectomy | 0.79 (0.58, 1.06) | 0.12 |

| Alk Phos: above vs. below median | 1.24 (0.92, 1.68) | 0.26 |

| Hgb: above vs. below median | 0.84 (0.62, 1.14) | 0.26 |

| Progression by 90 days: Yes vs. No | 2.10 (1.50, 2.92) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: Alk Phos – alkaline phosphatase, Hgb – hemoglobin, CI – confidence interval

Discussion

In this updated analysis of S8949, palliative debulking nephrectomy was again confirmed to improve survival in patients with advanced RCC. A hazard ratio for survival of 0.74 was seen in favor of the nephrectomy arm. In addition, the benefit for nephrectomy was seen across all pre-defined patient strata, including performance status, presence or absence of lung metastases, and the presence or absence of measurable disease. These results further solidify the role of debulking nephrectomy as a principal therapeutic modality in the management of advanced RCC.

We also performed post-hoc univariate and multivariate analyses that identified clinical variables prognostic for survival. These variables typically reflect underlying aggressive tumor biology manifesting clinically as reduced performance status, early disease progression, or tumor bulk. In one of our multivariate models, early progression within 90 days appeared to be an even stronger prognostic indicator for survival than performance status. This finding suggests that the presence of de novo or early resistance to systemic therapy is a principal determinant of patient outcome. Not surprisingly, these results mirror similar findings in other solid tumors such as non-small cell lung cancer.12 These data can stimulate efforts to identify specific molecular or clinical biomarkers that can accurately predict which patients will experience early disease progression on standard systemic therapy. Once identified, these patients should subsequently be considered for investigational therapies upfront rather than receiving traditional systemic therapies.

Our conclusions from this trial are based on rapidly evolving context where interferon was the principal outpatient systemic therapy available to community physicians. Whether the prognostic factors identified herein will have the same association with survival for trials with newer targeted agents (such as angiogenesis- and mTOR-inhibitors) may need to be assessed in subsequent trials. What may be more valuable is to define predictive factors which indicate groups of patients who are more or less likely to respond to a particular treatment. In S8949, we were unable to identify any predictive factors for nephrectomy since that modality’s efficacy benefit was observed across all pre-specified patient subsets.

In conclusion, this updated analysis of S8949 confirmed the role of palliative debulking nephrectomy in the RCC therapeutic armamentarium. Our data should stimulate further study of clinical or molecular biomarkers for early progression or resistance. It is planned that these results will be employed in the design and conduct of future SWOG trials.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS: CA-32102, CA-38926, CA-46441, CA-46282, CA-42777

References

- 1.Nelson EC, Evans CP, Lara PN. Renal cell carcinoma: current status and emerging therapies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2007;33(3):299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, et al. Survival and Prognostic Stratification of 670 Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(8):2530–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz L, et al. Prognostic Factors for Survival in Previously Treated Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22 (3):454–463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mekhail TM, Abou-Jawde R, BouMerhi G, et al. Validation and Extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Prognostic Factors Model for Survival in Patients With Previously Untreated Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(4):832–841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Figlin R, et al. Validation of the UCLA Integrated Staging System for Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19(17):3792–3793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.17.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rini B, Vogelzang NJ. Prognostic factors in renal carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensalah K, Leray E, Fergelot P, et al. Prognostic value of thrombocytosis in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;175:859–863. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HL, Seligson D, Liu X, et al. Using tumor markers to predict the survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:1496–1501. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154351.37249.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashyap MK, Kumar A, Emelianenko N, et al. Biochemical and molecular markers in renal cell carcinoma: an update and future prospects. Biomarkers. 2005;10:258–294. doi: 10.1080/13547500500218534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1655–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lara PN, Redman M, Kelly K, Edelman M, Williamson S, Crowley J, Gandara DR. Disease Control Rate at Eight Weeks Predicts Clinical Benefit in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results from Southwest Oncology Group Randomized Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(3):463–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]