Abstract

Although leukocytes infiltrate the kidney during ischemic acute kidney injury (AKI) and release interleukin 6 (IL6), their mechanism of activation is unknown. Here, we tested whether Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on leukocytes mediated this activation by interacting with high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) released by renal cells as a consequence of ischemic kidney injury. We constructed radiation-induced bone marrow chimeras using C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScNJ strains of TLR4 (−/−) mice and their respective TLR4 (+/+) wild-type counterparts and studied them at 4 h after an ischemic insult. Leukocytes adopted from TLR4 (+/+) mice infiltrated the kidneys of TLR4 (−/−) mice, and TLR4 (−/−) leukocytes infiltrated the kidneys of TLR4 (+/+) mice but caused little functional renal impairment in each case. Maximal ischemic AKI required both radiosensitive leukocytes and radioresistant renal parenchymal and endothelial cells from TLR4 (+/+) mice. Only TLR4 (−/−) leukocytes produced IL6 in vivo and in response to HMGB1 in vitro. Thus, following infiltration of the injured kidney, leukocytes produce IL6 when their TLR4 receptors interact with HMGB1 released by injured renal cells. This underscores the importance of TLR4 in the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, acute renal failure, inflammation, ischemia–reperfusion, ischemic renal failure

Ischemic acute kidney injury (AKI) is ameliorated after transgenic knockout of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) gene1 in C57BL/6 mice.2–5 However, the precise mechanisms of how TLR4 regulates ischemic AKI remain to be fully elucidated. Most attention has previously been directed at TLR4 on renal tubules.2,5 The major goal of this manuscript is to determine whether TLR4 on leukocytes, in addition to tubules, has a major impact on ischemic AKI. This is an important question because many leukocytes do express TLR4,6–9 renal leukocytes do exacerbate ischemic AKI,10–15 and we do not fully understand how renal leukocytes are activated during ischemic AKI. An attractive hypothesis would be activation via interactions between TLR4 on leukocytes and the TLR4 ligand high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) released by renal cells injured during ischemic AKI.16–20 Previous efforts to determine the role of TLR4 on leukocytes have used bone marrow (BM) chimeras between TLR4 (+/+) and TLR4 (−/−) mice to examine the contribution of TLR4 on radiosensitive BM-derived cells (presumably leukocytes) and TLR4 on radioresistant renal parenchymal cells. These studies have yielded conflicting results.2,3 We will use a combination of techniques to address this issue. We will reevaluate ischemic AKI in BM chimeras constructed with high-dose irradiation, and we will also analyze TLR4 expression in kidneys from chimeric mice. We will develop techniques to isolate leukocytes from TLR4 (+/+) versus TLR4 (−/−) kidneys, and then determine whether TLR4 on leukocytes is required for their production of interleukin 6 (IL6), which is known to exacerbate ischemic AKI.21,22

The beneficial effect of TLR4 inactivation on ischemic AKI was previously based on transgenically knocking out TLR4 in a single mouse strain.2,3 Attempts to extend results from a single strain of inbred mouse to outbred humans has sometimes led to disappointment because modifier genes in the outbred genetic background canceled the effect of the knockout.23–25 We now demonstrate the effects in TLR4 mutation in several strains of mice; this suggests that these effects are sufficiently powerful to overcome any modifier genes. Considering modifier genes is especially cogent for ischemic AKI because the genetic background does affect the course of this disease26 and other genes, in addition to TLR4, affect ischemic AKI27–31 and could interact with TLR4. Finally, we will use spontaneous mutations of TLR4. These overcome the possibility of unintended effects on ischemic AKI of the neomycin cassette, and 129 genetic materials introduced into the C57BL/6 genome during the transgenic knockout of TLR4 (refs 1, 25) used in previous studies.2,3

RESULTS

Spontaneous mutations of TLR4 on different genetic backgrounds ameliorate ischemic AKI

We compare ischemic AKI in the TLR4 (−/−) C3H/ HeJ mouse with its wild-type progenitor, and ischemic AKI in the TLR (−/−) C57BL/10ScNJ with its wild-type progenitor. The former C3H genetic background is unrelated both by genealogy32 and also by single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis33 from the previously studied C57BL/6 mouse.2,3 The latter C57BL/10 genetic background is also significantly different from the previously studied mouse.34,35 The TLR4 (−/−) C3H/HeJ has a spontaneous point mutation in the cytoplasmic part of TLR4 that prevents known intracellular signaling.36–42 The C57BL/10ScNJ has a complete deletion mutation of TLR4.41–44

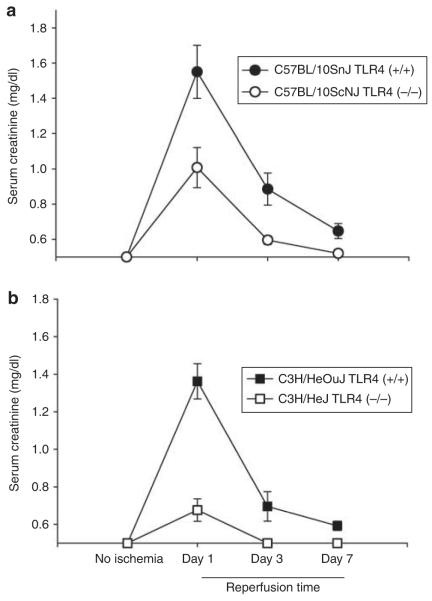

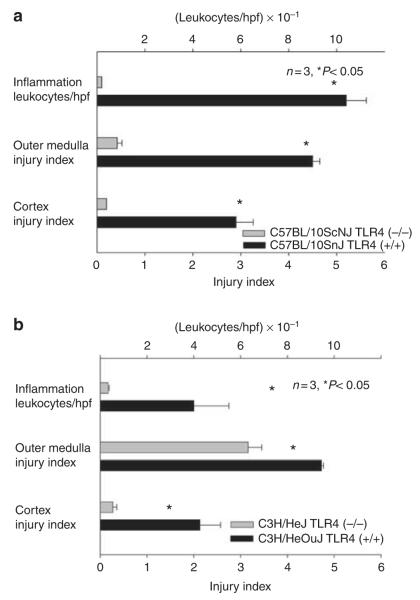

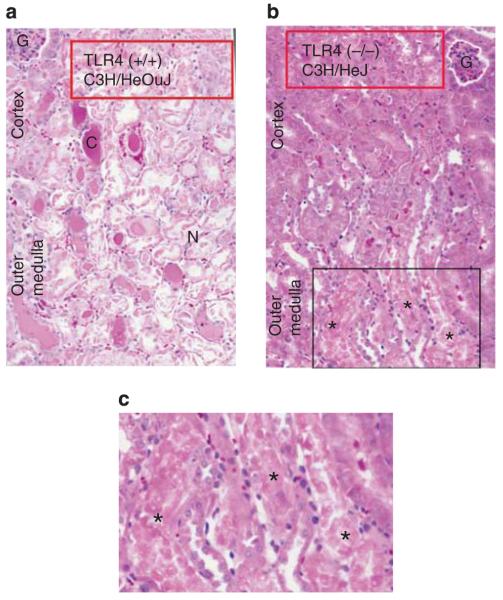

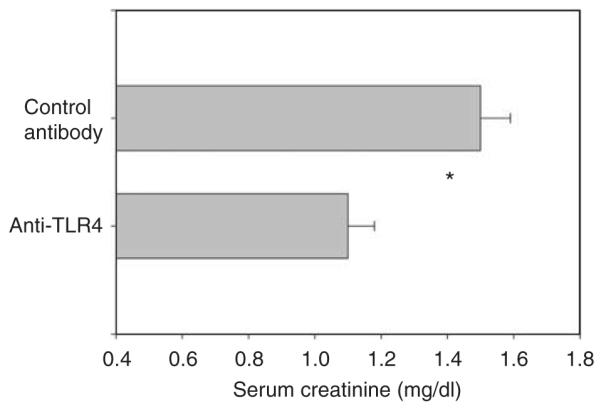

Both mutations provided protection from ischemic AKI. Figure 1a and b show that both mutant mice have less functional impairment than their wild-type counterparts. Examination of renal histology showed that both mutant mice also had less injury and less inflammation at 24 h reperfusion. This pathology is summarized as morphometry in Figure 2, and representative photomicrographs are shown in Supplementary Figure S1AB online, Supplementary Figure S1CD online, and Figure 3. Morphometry was performed by our renal pathologist, Dr Zhou. He neither knew the mouse strain nor treatment when he scored the renal pathology. Note that Figure 3c shows that although there was much less injury in the TLR4 (−/−) kidneys, some necrosis in the outer medulla was present. In addition to the point and null mutations discussed above, we also treated ischemia AKI in wild-type mice with anti-TLR4 antibodies. This also ameliorated ischemic AKI (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Spontaneous mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) ameliorate ischemic acute kidney injury as assessed by renal function.

In both a and b, n = 5, means and standard errors are shown. P<0.05 between the TLR4 (+/+) versus the TLR4 (−/−) at 1- and 3-day reperfusion.

Figure 2. Spontaneous mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) ameliorate ischemic acute kidney injury—morphometrics of injury and inflammation.

Morphometry calculated according to Thurman et al.86 injury was scored on a scale of 0–5, where 0 was no tubular injury and 5 was maximal tubular injury. The number of inflammatory cells was also counted. Kidneys were harvested at 24 h reperfusion. Mean and standard errors are shown. hpf, high-power field.

Figure 3. Spontaneous Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-inactivating mutation in C3H/HeJ mice ameliorates the pathology of ischemic acute kidney injury.

(a) Representative pathology of TLR4 (+/+) kidneys at 24 h reperfusion. C, cast in tubule; G, glomerulus; N, severely damaged necrotic tubule that has disintegrated. (b) Representative pathology of TLR4 (−/−) kidneys at 24 h reperfusion. (c) Enlargement of the boxed area of b. Three necrotic tubules (*) in the outer medulla of the TLR4 (−/−) kidneys.

Figure 4. Anti-Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antibody ameliorates ischemic acute kidney injury in wild-type (C57BL/10ScNJ) mice.

n = 4 for each group. Mean and standard errors are shown. *P<0.05 between groups. Mice received anti-TLR4 or isotype control antibody intravenously 3 h before ischemia, and serum creatinine was measured at 24 h reperfusion.

BM chimeras show that TLR4 on both radioresistant and radiosensitive cells are required for maximal injury after acute ischemia

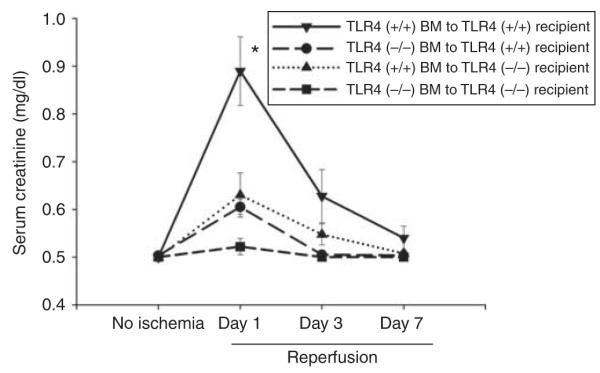

Using the spontaneous inactivating TLR4 mutations above, our major goal is to determine whether TLR4 on leukocytes participates in ischemic AKI. We used a number of techniques to address this question. We first used BM chimeras between TLR4 (−/−) and TLR4 (+/+) mice to determine whether the TLR4 cells contributing to ischemic AKI are radioresistant or radiosensitive (presumably leukocytes). We made BM chimeras between C3H/HeJ (TLR4 −/−) and C3H/HeOuJ TLR4 (+/+) mice, and found that maximal ischemic AKI requires functional TLR4 on both radiosensitive leukocytes and radioresistant renal parenchymal cells. See Figure 5. As these mice differ only in a point mutation, it was not possible to confirm success of the BM transplant by genomic PCR of the blood.

Figure 5. Maximal ischemic acute kidney injury requires Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in both radiosensitive and - resistant cells: chimeras between C3H/HeJ and C3H/HeOuJ mice.

n = 5 per group; mean and standard errors shown. *P<0.05 between group A and each other group. BM, bone marrow.

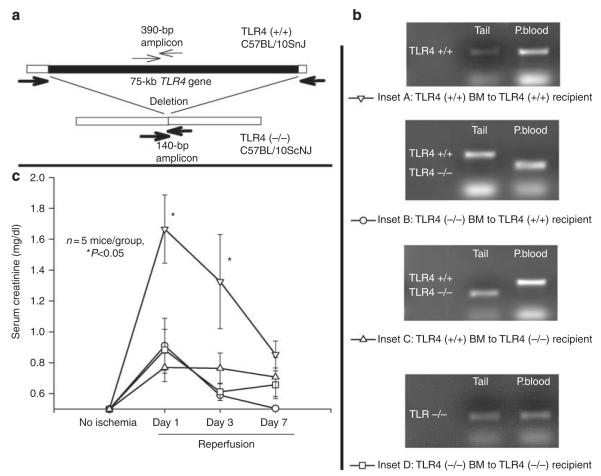

Such independent confirmation was possible when we studied chimeras of C57BL/10ScNJ (TLR4 (−/−)) and C57BL/10SnJ (TLR4 (+/+)) mice (Figure 6). Figure 6a shows our PCR strategy for + detecting the TLR4 deletion versus wild-type TLR4. Figure 6b shows confirmation of the various chimeras by genomic PCR for TLR4 in their blood leukocytes versus their radioresistant tails. We confirmed the chimerism of all mice before inducing ischemic AKI. Figure 6c shows that maximal ischemic AKI required major contributions from both radioresistant and radiosensitive cells.

Figure 6. Maximal ischemic acute kidney injury requires Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in both radiosensitive and -resistant cells: chimeras between C57BL/10ScNJ and C57BL/10SnJ mice.

(a) The specific PCR primers for a region within the TLR4 gene (fine arrows) result in a 390-bp amplicon only in TLR4 (+/+) cells. The primers flanking the wild-type TLR4 gene do not yield a product in TLR4 (+/+) cells because of the large size of the TLR4 gene, but do result in a 140-bp amplicon in TLR4 (−/−) cells. (b) The insets show representative genomic PCR of the tail and peripheral blood (P.blood) of the bone marrow (BM) chimeras. (c) The serum creatinine at the indicated days of reperfusion in the various chimeric mice. No ischemia, serum creatinine taken before ischemia. The symbols are defined in b. *P<0.05 between the TLR4 (+/+) BM to TLR4 (+/+) chimera versus each other group at days 1 and 3 of reperfusion.

Overall, these two sets of chimeras, involving two different pairs of TLR4 (+/+)/TLR4 (−/−) mice, suggest that radiosensitive leukocytes are required for the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI. We now use additional techniques to test this requirement.

TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes are found in the inner stripe of the outer medulla of TLR4 (−/−)-irradiated recipient kidneys after ischemic AKI

If TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes are required for ischemic AKI, we predict that they, like other leukocytes,13,45–47 should infiltrate the inner stripe of the outer medulla (ISOM) after ischemic injury (Figure 7). In other words, we should find TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes in the ISOM of chimeras where TLR4 (−/−)-irradiated hosts receive TLR4 (+/+) BM (group C of Figure 7a). TLR4-positive leukocytes are difficult to demonstrate by immunohistology, perhaps because they express very little TLR4.48 We therefore used an alternative approach to test our prediction; we dissected the various regions of the kidney and analyzed the regions for TLR4 by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR. The results below suggest that TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes do indeed infiltrate the ischemic ISOM.

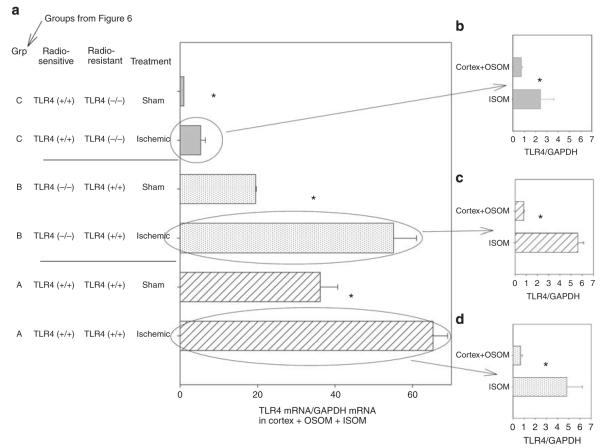

Figure 7. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression in the chimeric kidney during ischemic acute kidney injury: bone marrow (BM) chimera constructed between TLR4 (−/−) C57BL/10ScNJ and TLR4 (+/+) C57BL/10J mice.

Chimeras constructed as in Figure 7. Kidneys harvested at 4 h reperfusion. (a) TLR4 in sham versus ischemic chimeric kidneys. The ischemic kidneys were then dissected into the inner stripe of the outer medulla (ISOM) versus the combined cortex + outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM), and TLR4 compared. (b) TLR4 in ischemic TLR4 (+/+) BM to TLR4 (−/−) kidneys. (c) TLR4 in ischemic TLR4 (−/−) BM to TLR4 (+/+) kidneys. (d) TLR4 in ischemic TLR4 (+/+) BM to TLR4 (+/+) kidneys. The x axis is the TLR4 mRNA determined by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR by the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) the method. The TLR4 Ct is normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Ct from the same sample. The calibrator gene is the TLR4 in the sham kidney from the group C in panel a. N = 3; the mean and standard errors are shown. *P<0.05 between groups.

At 4 h reperfusion, gross changes in the ischemic kidney allow its dissection into three separate compartments:49–51 The first compartment is the ISOM and is distinguished by congestion of red cells (Supplementary Figure S2 online). The second compartment consists of the cortex OSOM (outer stripe of the outer medulla) and is identified as the pale structure outside the congested ISOM. The third compartment is the inner medulla and is identified by its characteristic papillary shape. In contrast to the ischemic kidney, there is no vascular congestion in the ISOM of the sham kidney, and this region cannot be distinguished from the OSOM + cortex. Thus, to compare sham with ischemic kidneys, we dissected the kidneys into two compartments. One contained the ISOM + OSOM + cortex and the other contained the inner medulla (papilla).

Analysis of TLR4 by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR in these compartments demonstrated that ischemia increased renal TLR4 in the chimeras of TLR4 (+/+) BM to irradiated TLR4 (−/−) recipients (Figure 7a, group C). This increased TLR4 was in the ISOM (Figure 7b). This observation is consistent with the prediction that TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes infiltrate the ISOM after ischemia. However, there was little ischemic AKI in this chimera (Figure 6, group C), because TLR4 was also required on the radioresistant cells. This issue is addressed in the Discussion section.

Ischemia also increased renal TLR4 in the TLR4 (−/−) BM to TLR4 (+/+)-irradiated recipient (Figure 7a, group B). The ISOM had greater increases in TLR4 than the cortex and OSOM (Figure 7c). Increased TLR4 on radioresistant cells in the ISOM is consistent with ischemia, directly increasing TLR4 expression on endothelia of the ISOM.52 The results are consistent with the importance of leukocyte TLR4 in the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI because despite the increased TLR4 on radioresistant cells, there was little functional renal impairment in these chimeras (group B, Figure 6). This may be due to the absence of leukocyte TLR4 in these chimeras.

We also found increased TLR4 in the ISOM during ischemic AKI when both radiosensitive and -resistant cells expressed TLR4 (Figure 7a, group A—TLR4 (+/+) BM to TLR4 (+/+), and Figure 7d). This is consistent with the direct ischemia-induced increased endothelial TLR4 that we previously reported,52 plus infiltration with TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes. Expression of TLR4 on both radiosensitive and -resistant cells was associated with functional impairment (group A, Figure 6). This confirmed that the radiation chimeras responded similarly to the intact TLR4 (+/+) mouse after clamping the renal pedicle for 17 min.

Only TLR4 (+/+) CD45+ renal leukocytes produce maladaptive IL6 in response to HMGB1 during ischemic AKI

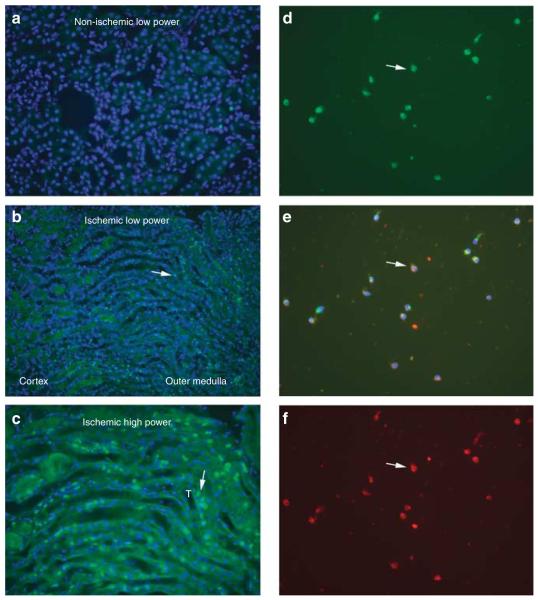

If TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes are required for maximal ischemic AKI, we predict that these leukocytes should produce maladaptive cytokines in response to TLR4 ligands released by renal cells injured during ischemic AKI. Before testing this prediction, we show that renal leukocytes do indeed express TLR4 protein. Although previous work showed that ischemia/reperfusion increased TLR4-expressing interstitial cells,2 and increased leukocytes in the outer medulla,53 the TLR4-expressing cells were not formally identified as leukocytes. We now show increased macrophages at 4 h reperfusion by immunofluorescence (Figure 8a–c). We were unable to double immunostain with macrophage markers and TLR4. Therefore, we isolated these macrophages from wild-type ischemic kidneys by density centrifugation and adherence to slides, and showed that they all expressed both the TLR4 protein and the macrophage marker F4/80 by double immunofluorescence (Figure 8d–f).

Figure 8. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) macrophages infiltrate the inner stripe of the outer medulla at 4 h reperfusion.

(a) Low-power view of non-ischemic kidney stained with F4/80 and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (b) Low-power view of ischemic kidney similarly stained. (c) High-power view of ischemic kidney similarly stained. (d–f) Renal leukocytes isolated by enzymatic dispersion, gradient centrifugation, and adherence at 4 h reperfusion. (d) Stained with F4/80 for macrophages (green fluorescence). (e) Merged d and f; F4/80 (green), TLR4 (red), and DAPI (blue). (f) Stained with TLR4 (red). White arrow in all three panels shows one of many leukocytes that stain both for F4/80 and TLR4, and also for nuclear DAPI. T, tubule.

We chose to study IL6 production by TLR4 (+/+) versus (−/−) renal leukocytes. This choice was based on four facts: the known detrimental effect of IL6 in ischemic AKI as previously demonstrated by the beneficial effect of anti-IL6 antibodies and transgenic knockout of IL6,21,22 the requirement for IL6 wild-type BM cells for maximal ischemic injury in chimeras involving IL6 knockout and wild-type mice, and the ability of molecules released by injured S3 proximal tubules to stimulate IL6 production by macrophages in vitro.22 Furthermore, stimulation of the TLR4 receptor is known to stimulate leukocyte IL6 production.54 Although most research has focused on TLR4 on macrophages and dendritic cells,6 TLR4 is also found on T cells,7 polymorphonuclear cells,8 and natural killer cells,9 and production of IL6 by these renal leukocytes may result from any of these leukocytes interacting with TLR4 ligands, Therefore, in some of the experiments below, we choose to isolate all of these leukocytes together using a common leukocyte cell surface marker—CD45.

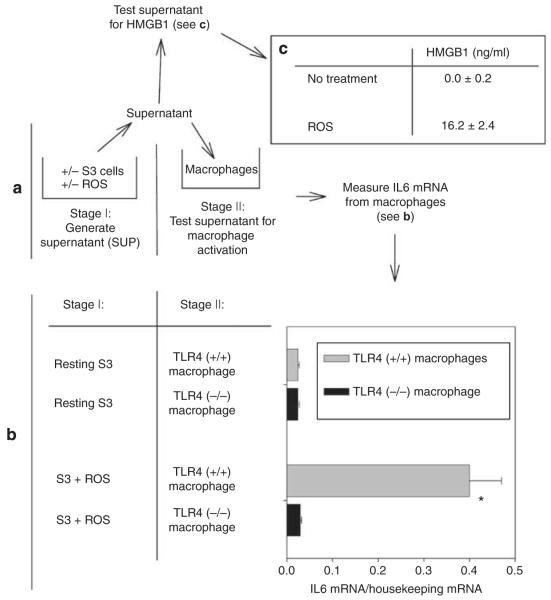

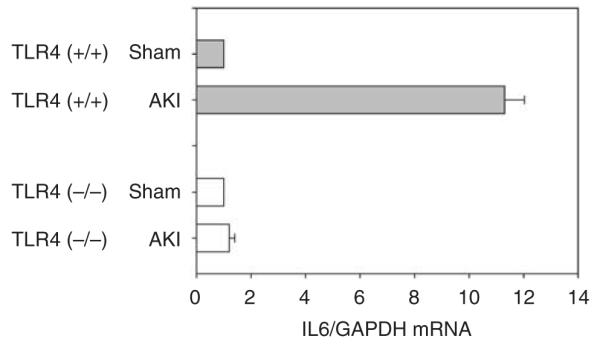

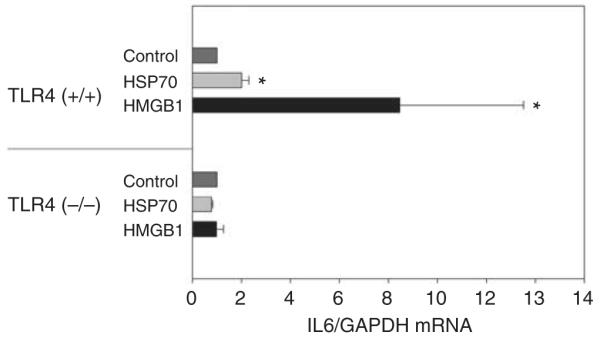

We used three different approaches to determine whether leukocytes produce maladaptive IL6 in a TLR4-dependent manner. (a) We used anti-CD45-conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to retrieve leukocytes from enzymatically dispersed kidneys. Figure 9 shows that leukocytes from TLR4 (+/+), but not TLR4 (−/−), kidneys express IL6 in vivo after ischemia. (b) To further determine whether production of maladaptive IL6 by these leukocytes was due to stimulation of their TLR4 receptors, we stimulated BM-derived macrophages with the TLR4 ligand HMGB1 and heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) in vitro. HMGB1 and HSP70 are ‘damage-associated molecular pattern molecules’ (alarmin)16,17,18,19,20 and are released by renal cells injured during ischemic AKI.2 Figure 10 shows that HMGB1 stimulates IL6 production leukocytes from TLR4 (+/+) mice to a much greater extent than HSP70; neither stimulated leukocytes from TLR4 (−/−) mice. (c) Furthermore, we developed an in vitro model of ischemic AKI.22 Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated not only during the reperfusion phase of ischemic AKI but also during hypoxia because of inefficient use of residual oxygen by mitochondria. Addition of ROS to renal tubular cells is an established model of ischemia/reperfusion in vitro.55–60 In this model (Figure 11), proximal tubule cells are injured by ROS. The ROS-treated S3 proximal tubular cells release HMGB1 into the tissue culture supernatant (Figure 11a and c). The HMGB1-containing supernatant stimulates only TLR (+/+) macrophages to produce IL6 (Figure 11a and b). We have previously demonstrated that ROS in the S3 supernatant does not stimulate production of IL6 by macrophages.22

Figure 9. Interleukin 6 (IL6) expressed only by CD45+ leukocytes from Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4; +/+) ischemic kidneys.

AKI, acute kidney injury; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Figure 10. High-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) and heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) stimulate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4; +/+) but not TLR4 (−/−) bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages: BM-derived macrophages stimulated in vitro with media, HSP70 (3 μg/ml), and HMGB1 (3 μg/ml).

Interleukin 6 (IL6) was measured by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR. Each sample normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The calibrator gene is the media-treated BMDM. n = 4. Means and standard deviation are shown. *P<0.05 between TLR4 (+/+) media, HSP70, and HMGB1 groups. TLR4 (−/−) mice were C57BL/10ScNJ, and TLR4 (+/+) mice were C57BL/10SnJ.

Figure 11. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-injured S3 renal tubular cells release Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) ligands.

(a) Experimental design. In stage I, the SV40-transformed S3 tubules were a gift from Dr Glenn Nagami.83 If they were injured by ROS, they released endogenous TLR4 ligands into their supernatant for 12 h. In stage II, the supernatant was cultured with murine bone marrow macrophages. (b) Only TLR4 (+/+) macrophages are activated by supernatant from ROS-stimulated S3 cells. TLR4 (+/+) macrophages are from C57BL/10SnJ mice. TLR4 (−/−) macrophages are from C57BL/10ScNJ mice. Results of typical experiment from four are shown. n = 3, mean and standard error are shown. *P<0.05 between S3 + ROS/TLR4 (+/+) macrophage and other groups by t-test. (c) High-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) in supernatants. n = 4. Mean and standard errors shown. P<0.05 between no treatment and ROS groups. IL6, interleukin 6.

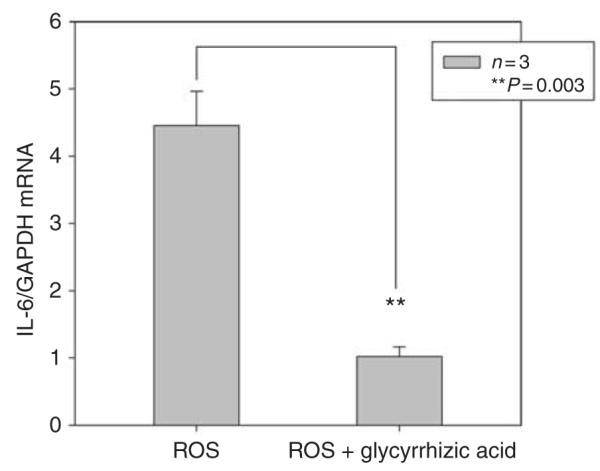

Although the concentration of HMGB1 in the supernatant of injured S3 cells (Figure 11) is lower than the concentration of purified HMGB1 necessary to stimulate macrophages (Figure 10), HMGB1 in the supernatant is necessary for stimulation of macrophages because inactivation of HMGB1 by glycyrrhizic acid markedly diminished the stimulatory activity of the supernatant (Figure 12). Glycyrrhizic acid specifically inactivates HMGB1 by specifically binding to both active domains of HMGB1.61,62 Although the physiological concentrations of HMGB1 in injured tissues is not known, the concentration of purified HMGB1 that we used in Figures 10 and 12 is similar to those used by others in vitro.63 Why such large amounts of purified HMGB1 are necessary to achieve the stimulation of lesser amounts of HMGB1 in biological fluids is not known with certainty. Explanations include the release of co-stimulatory cytokines or post-translational modification of HMGB1 by stressed cells so that HMGB1 in the supernatant is more stimulatory than purified HMGB1.64,65

Figure 12. Inhibition of high-mobility group protein B1 by glycyrrhizic acid prevents stimulation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4; +/+) macrophages.

S3 cells treated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) as in Figure 11. Their supernatant was added to TLR4 (+/+) macrophages in the of presence or absence glycyrrhizic acid. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IL6, interleukin 6.

Endotoxin was not responsible for the stimulatory effect of our HMGB1 (1690-HM, lot MHZ24 from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) that contained less than 0.00855 EU/μg. Our HSP70 (ESP-f555, lot 0829062) contained <0.005 EU/μg. Heat inactivated the stimulatory activity of our HMGB1 and HSP70 by 98%; this indicates that it is a protein because endotoxin is not inactivated by such heating.

DISCUSSION

In this manuscript, we further established the role of TLR4 in ischemic AKI by using mice with spontaneous mutations that inactivate TLR4. The C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScNJ strains used in our report are unrelated both by their genealogy32 and also by single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis.33 The fact that mutations in a single gene, TLR4, should have such profound effects in such unrelated mice is an additional powerful genetic argument for the great importance of TLR4 in the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI. This work confirms and extends previous work that used a single transgenic knockout of TLR4 on the C57BL/6 genetic background.2,3

In this manuscript, we suggest that TLR4-mediated activation of leukocytes is one factor contributing to ischemic AKI extension. We provide several lines of data consistent with this hypothesis.

First, our radiation chimeras between two different pairs of TLR4 (+/+) and TLR4 (−/−) mice (C3H/HeJ and C3H/ HeOuJ, and C57BL/10ScNJ and C57BL/10SnJ) are strong arguments for the participation of TLR4 on both radioresistant and radiosensitive (presumable leukocyte) cell populations in the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI (Figures 5 and 6). Our data is consistent with Pulskens et al.3 but shows a much greater contribution of radiosensitive TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes compared with the report of Wu et al.2 The key chimera is the TLR4 (−/−) BM in the TLR4 (+/+)-irradiated recipient. The key question is whether all TLR4 (+/+) BMs are eliminated by the irradiation. We and Pulskens used two doses of 5 Gy for a total dose of 10 Gy, whereas Wu 2 used one dose of 9 Gy. Our higher dose of irradiation might have functionally eliminated all the TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes in the irradiated TLR4 (+/+) recipient. In contrast, the smaller dose of irradiation in the Wu study might have allowed a functionally significant number of TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes to survive in the irradiated recipient. These survivors may have proliferated while the mice were recovering from the irradiation and BM transplant, and these survivors and their progeny may have contributed to a TLR4 (+/+) inflammatory response to ischemia and the severe AKI seen in the Wu TLR4 (−/−) BM to irradiated TLR4 (+/+) recipient group.2

Second, we analyzed sham and ischemic kidneys from chimeric mice. We found that TLR4 (+/+) BM cells, presumably leukocytes, infiltrate the ischemic kidney of TLR4 (−/−) recipients (group C, Figure 7a). This is consistent with TLR4 expression by leukocytes and infiltration of these TLR4-expressing leukocytes into the kidney in response to ischemia. To our knowledge, this is the first such analysis of TLR4 expression in ischemic kidneys from chimeric mice.

Despite the presence of TLR4 (+/+) BM cells, presumed leukocytes, in the ischemic kidneys of irradiated TLR4 (−/−) recipients, there was little ischemic AKI in these chimeras (Figure 6). One would expect that any TLR4 (+/+) renal leukocyte would be stimulated by HMGB1 released by injured ischemic renal cells and would produce maladaptive IL6, as discussed in the next paragraphs, and injure the kidney. We believe that injury did not occur because although a sufficient number of TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes infiltrated the TLR4 (−/−) kidneys to be detected, there was an insufficient number to damage the kidney. We previously showed that endothelial TLR4 is required for the increased expression of adhesion molecules necessary for an efficient inflammatory response to renal ischemia.52 Radioresistant endothelial cells would be TLR4 (−/−) in the irradiated TLR4 (−/−) recipient. Absent this endothelial TLR4, there would be no increased adhesion molecule expression, and too few TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes would be able to infiltrate the ischemic kidney significantly damage it.66 However, in wild-type kidneys, endothelial TLR4 would be present, endothelial adhesion molecules would therefore increase during ischemic AKI, and there would be efficient inflammation by TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes. Thus, both the TLR4 on radioresistant endothelia and the TLR4 on radiosensitive leukocytes together cause the vigorous inflammatory response that exacerbates ischemic AKI.

Consistent with the above reasoning, we did not find statistically significant differences between IL6 mRNA when TLR4 (−/−) BM was transplanted into TLR4 (+/+) recipients versus when TLR4 (+/+) BM was transplanted into TLR4 −/− recipients. We believe that the similar low levels of IL6 occurred in these two groups because the TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes could not immigrate into the ischemic TLR4 (−/−) renal tissue, as discussed above.

Third, we developed a technique for isolating renal leukocytes from ischemic kidneys. We found that only leukocytes from TLR4 (+/+) kidneys produce maladaptive IL621,22 during ischemic AKI in vivo (Figure 9).

Fourth, we also found that TLR4 (+/+), but not TLR4, (−/−) leukocytes produce IL6 in response to HMGB1 released by cells damaged during ischemia in vitro (Figure 10).

Fifth, we demonstrate a role for TLR4 (+/+) macrophages in an in vitro model of ischemic AKI. In this model, proximal tubule cells release HMGB1 after injury by ROS and this HMGB1 stimulates TLR4 (+/+), but not TLR4 (−/−), macrophages to produce IL6 (Figure 11). This increase in IL6 from macrophages can be attenuated by glycyrrhizic acid, an inhibitor of HMGB161,62 (Figure 12).

The contribution of TLR4 (+/+) leukocytes to the pathogenesis of ischemic AKI, suggested by our data, is consistent with the literature because of the known expression of TLR4 on leukocytes6–9 and the known contribution of leukocytes to ischemic AKI.10–15 How leukocytes are activated during ischemic AKI remains to be fully understood. However, our data suggest that one pathway of activation is stimulation of leukocyte TLR4 by HMGB1, which are released by injured cells.

We acknowledge that other members of the family of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and their ligands (for example, RAGE, TLR2, TLR9 and IL1) may also participate in ischemic AKI.16,67–74 We chose to focus on the HMGB1–TLR4 axis because direct molecular interactions between HMGB1 and TLR4 have recently been demonstrated,75 because antibodies against HMGB1 ameliorate ischemic AKI,76,77 and transgenic knockout2–5 and spontaneous mutagenesis (Figures 1 and 2) and antibodies to TLR4 (Figure 4) ameliorate ischemic AKI. Furthermore, Figure 10 shows that another TLR4 ligand HSP70 also activates IL6 production by macrophages, but much less effectively than HMGB1.

In conclusion, TLR4 was initially demonstrated on renal tubular cells after 24 h reperfusion.2,3,78,79 We have recently demonstrated endothelial expression of TLR4 at 4 h reperfusion and showed that renal endothelial TLR4 was required for expression of adhesion molecules. These adhesion molecules allow the maladaptive inflammatory response to ischemic injury at 4-h reperfusion.52 In this manuscript, we report that after leukocytes infiltrate the injured kidney, they produce maladaptive IL6 when their TLR4 receptors interact with HMGB1 released by injured renal cells. Thus, at least three cell types (epithelia, endothelia, and leukocytes) express TLR4 at various times during ischemic AKI; each may have different roles during ischemic AKI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury

Six- to eight-week male TLR4 (−/−) C57BL/10ScNJ mice were used. (This strain has other names—C57BL/10ScN, C57BL/10ScNCr, and C57BL/10ScCr.) It has a deletion of TLR4 but a normal IL12R. See http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/003752.html), and C3H/HeJ and the wild-type progenitor strains C57BL/10SnJ and C3H/HeOuJ were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) or the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). A right nephrectomy and left renal pedicle occlusion were performed under isoflurane anesthesia, while the rectal temperature was maintained at 37 °C. Sham mice underwent the same procedure except, instead of occluding the renal pedicle, the clip was placed underneath the pedicle. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UT Southwestern Medical Center. Some mice received 30 μg of functional grade (no NaN3), rat anti-mouse TLR4/MD2 monoclonal antibody (MTS510, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) intravenously 3 h before renal ischemia. Functional grade purified rat IgG2a isotype (eBioscience) was the control.

BM chimeras

These were constructed as previously reported by our group.22,80 Briefly, recipient mice were irradiated with two doses of 5 Gy and injected intravenously with 8 × 106 BM cells. After hematopoietic reconstitution, mice were maintained in a sterile environment for 8–10 weeks before analyses for chimerism. Chimerism between the C57BL/10ScNJ and C57BL/10J was confirmed by PCR using published primers.81 Genomic DNA from tail and blood was extracted using Extract-N-Amp Tissue/Blood PCR kit (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Leukocyte isolation from ischemic kidneys

Kidney tissues collected at 4-h reperfusion were minced into 1–2 mm fragments and dissociated in phosphate-buffered saline with Liberase Blendzyme 3 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN; 0.18 Wünsch U/ml) at 37 °C for 20 min. In all, 25 μl of Dynabeads Sheep anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen) was coated with 1.5 μg of rat anti-mouse CD45 (30F11, eBioscience). Tissue digest was filtered through 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The single-cell solution was then incubated with Dynabeads at 4 °C with gentle tilting and rotation for 30 min. Total RNA was extracted from bead-bound CD45+ cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

BM-derived macrophages

Our technique for BM macrophage expansion came from Brunt et al.82 By flow cytometry, over 95% of the expanded BM cells at 7 days were macrophages, as defined by their F4/80 positivity. Macrophage cells were treated with either ROS-stressed S3 supernatant, recombinant human HMGB1 (rhHMGB1, R&D Systems) with or without 100 μmol/l glycyrrhizic acid (Sigma), or heat shock protein 70 (Stressgen, San Diego, CA) for 4 h.

Treatment of S3 Cells with ROS

The SV-40 transformed S3 tubular cells83 were maintained as previously described.84 Confluent cultures were serum starved overnight and then placed into a solution containing 100 μl of 88 mg Hypoxanthine (Sigma)/ml in 1 mol/l Sodium Hydroxide (Sigma) and 50 μl of Xanthine Oxidase (diluted 1:10 in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen)). Supernatants were tested after 24 h of treatment.

Measurement of HMGB1 in ROS-stressed S3 supernatant: HMGB1 protein was measured using HMGB1 ELISA Kit II according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Shino Test, Tokyo, Japan).

Total RNA extraction and real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR

Kidney tissues were disrupted using PowerGen 700 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Total RNA was extracted by RNeasy Midi Kit. Total RNA from the macrophage cells or CD45+ cells was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kits, RNA was treated with Turbo DNA-free kit (Applied Biosystems, ABI, Carlsbad, CA) to remove genomic DNA. In all, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (ABI). Confirmation and relative quantitation of TLR4 and IL6 were performed using SYBR Green PCR Reagents and an ABI StepOnePlus Real-time PCR System according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were analyzed in triplicate. Comparative cycle threshold method was used. The cycle threshold of each gene of interest was normalized to the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase cycle threshold determined under the same conditions. The calibrator gene and the number of replicates are specified in each figure legend.85 The results are expressed as the gene of interest/glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA. The specific PCR primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) used were as follows: TLR4, forward primer 5′-AAACGGCAACTTGGA CCTGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGCTTAGCAGCCATGTGTTC CA-3′; IL6, forward primer 5′-GGACCAAGACCATCCAATTCA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGCACTAGGTTTGCCGAGTAG-3′.

Gradient cell isolation and immunohistochemistry

Mononuclear cells from ischemic kidneys at 4-h reperfusion were isolated using 1-Step 1.077 Animal (Nycodenz, Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation, Westbury, NY). Tissue dissociation was the same as above. Tissue lysates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and loaded on top of Nycodenz, centrifuged at 600 g for 20 min with brake off. Cells harvested from the interface were washed with phosphate-buffered saline at 400 g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended with DMEM plus 10% FCS and cultured on 8-well Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) for overnight. Attached cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min, and blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min. For double staining of TLR4 and F4/80, monoclonal rat anti-mouse TLR4 (R&D Systems), goat anti-rat-Texas Red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), rat anti-mouse F4/80-FITC (eBioscience), and goat anti-FITC Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) were sequentially applied to sections. VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories) was used to stain the nuclei. Rat IgG2a was used as isotype control. Fluorescent images were captured using Carl Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY). To prepare ischemic kidney sections for F4/80 staining, the left kidney was in situ perfused with cold phosphate-buffered saline and followed by cold 4% paraformaldehyde. The kidney was removed, cut sagittally and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 1C for 2 h, and transferred into 20% surcrose for cryoprotection. Kidney samples were then embedded with OCT (Tissue-Tek, Sakura, Torrance, CA) and snap frozen in isopentene on dry ice. Eight-micrometer thick sections were cut on Leica Cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Richmond, IL) and mounted onto superfrost-plus slides (Thermo Scientific, Portsmouth, NH).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH RO-1 DK069633 and a Beecherl Foundation Grant to CYL; NIH F32DK084701 and T32DK07257 to JRH; and the NIH DK079328 UT Southwesterrn O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center. We thank Thomas Carroll for the low-power photography and Kathy Trueman for assistance in preparing the manuscript and figures.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE All the authors declared no competing interests.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ki

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, et al. TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2847–2859. doi: 10.1172/JCI31008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulskens WP, Teske GJ, Butter LM, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 coordinates the innate immune response of the kidney to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusai K, Sollinger D, Baumann M, et al. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, et al. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3390–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810169106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutler B. Microbe sensing, positive feedback loops, and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:248–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Fine S, Law J, et al. TLR4 signaling in effector CD4+ T cells regulates TCR activation and experimental colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:570–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI40055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Frey RS, Malik AB. TLR4 signaling induces TLR2 expression in endothelial cells via neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1234–1243. doi: 10.1172/JCI18696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawaki J, Tsutsui H, Hayashi N, et al. Type 1 cytokine/chemokine production by mouse NK cells following activation of their TLR/MyD88-mediated pathways. Int Immunol. 2007;19:311–320. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutton TA, Fisher CJ, Molitoris BA. Microvascular endothelial injury and dysfunction during ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1539–1549. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemoto T, Burne MJ, Daniels F, et al. Small molecule selectin ligand inhibition improves outcome in ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2205–2214. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly KJ, Williams WW, Jr, Colvin RB, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice are protected against ischemic renal injury. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1056–1063. doi: 10.1172/JCI118498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Greef KE, Ysebaert DK, Persy V, et al. ICAM-1 expression and leukocyte accumulation in inner stripe of outer medulla in early phase of ischemic compared to HgCl2-induced ARF. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1697–1707. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedewald JJ, Rabb H. Inflammatory cells in ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;66:486–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Huang L, Sung SS, et al. NKT cell activation mediates neutrophil IFN-{gamma} production and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2007;178:5899–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oppenheim JJ, Tewary P, de la Rosa G, et al. Alarmins initiate host defense. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:185–194. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock KL, Kono H. The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:99–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton GM. A calculated response: control of inflammation by the innate immune system. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:413–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI34431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seong SY, Matzinger P. Hydrophobicity: an ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nri1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu CY, Hartono J, Senitko M, et al. The inflammatory response to ischemic acute kidney injury: a result of the ‘right stuff’ in the ‘wrong place’? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:83–89. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3280403c4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel NS, Chatterjee PK, Di Paola R, et al. Endogenous interleukin-6 enhances the renal injury, dysfunction, and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1170–1178. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kielar ML, John R, Bennett M, et al. Maladaptive role of IL-6 in ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3315–3325. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2003090757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadeau JH. Modifier genes in mice and humans. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:165–174. doi: 10.1038/35056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivera J, Tessarollo L. Genetic background and the dilemma of translating mouse studies to humans. Immunity. 2008;28:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisener-Dorman AF, Lawrence DA, Bolivar VJ. Cautionary insights on knockout mouse studies: the gene or not the gene? Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burne MJ, Haq M, Matsuse H, et al. Genetic susceptibility to renal ischemia reperfusion injury revealed in a murine model. Transplantation. 2000;69:1023–1025. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savransky V, Molls RR, Burne-Taney M, et al. Role of the T-cell receptor in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2006;69:233–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faubel S, Ljubanovic D, Reznikov L, et al. Caspase-1-deficient mice are protected against cisplatin-induced apoptosis and acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2202–2213. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Ljubanovic D, et al. Interleukin 18 mediated ischemic acute renal failure (ARF) in mice is neutrophil-independent. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:SA–FC152. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Huang L, Vergis AL, et al. IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:331–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI38702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donnahoo KK, Shames BD, Harken AH, et al. Review article: the role of tumor necrosis factor in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Urol. 1999;162:196–203. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck JA, Lloyd S, Hafezparast M, et al. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat Genet. 2000;24:23–25. doi: 10.1038/71641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wade CM, Kulbokas EJ, III, Kirby AW, et al. The mosaic structure of variation in the laboratory mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:574–578. doi: 10.1038/nature01252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekada K, Abe K, Murakami A, et al. Genetic differences among C57BL/6 substrains. Exp Anim. 2009;58:141–149. doi: 10.1538/expanim.58.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis SR, Dym C, Ginzberg M, et al. Genetic variance contributes to ingestive processes: a survey of mercaptoacetate-induced feeding in eleven inbred and one outbred mouse strains. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhee SH, Hwang D. Murine TOLL-like receptor 4 confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness as determined by activation of NF kappa B and expression of the inducible cyclooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34035–34040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukherjee S, Chen LY, Papadimos TJ, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-driven Th2 cytokine production in macrophages is regulated by both MyD88 and TRAM. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29391–29398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medvedev AE, Piao W, Shoenfelt J, et al. Role of TLR4 tyrosine phosphorylation in signal transduction and endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16042–16053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606781200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manthey CL, Perera PY, Henricson BE, et al. Endotoxin-induced early gene expression in C3H/HeJ (Lpsd) macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:2653–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zughaier SM, Zimmer SM, Datta A, et al. Differential induction of the toll-like receptor 4-MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling pathways by endotoxins. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2940–2950. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2940-2950.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qureshi ST, Lariviere L, Leveque G, et al. Endotoxin-tolerant mice have mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) J Exp Med. 1999;189:615–625. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poltorak A, Smirnova I, Clisch R, et al. Limits of a deletion spanning Tlr4 in C57BL/10ScCr mice. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:51–56. doi: 10.1177/09680519000060010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poltorak A, Merlin T, Nielsen PJ, et al. A point mutation in the IL-12R beta 2 gene underlies the IL-12 unresponsiveness of Lps-defective C57BL/10ScCr mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:2106–2111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gobe G, Willgoss DA, Hogg N, et al. Cell survival or death in renal tubular epithelium after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1299–1304. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashgarian M. Acute tubular necrosis an ischemic renal injury. In: Jennette JC, Olsen JC, Schwartz MM, Silva FG, editors. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. 5th edn vol.5. Lippincott—Raven; Philadelphia New York: 1999. pp. 863–889. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lieberthal W, Nigam SK, Bonventre JV, et al. Acute renal failure. I. Relative importance of proximal vs distal tubular injury. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F623–F631. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.5.F623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beutler BA. TLRs and innate immunity. Blood. 2009;113:1399–1407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-019307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mason J, Torhorst J, Welsch J. Role of the medullary perfusion defect in the pathogenesis of ischemic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1984;26:283–293. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto K, Wilson DR, Baumal R. Outer medullary circulatory defect in ischemic acute renal failure. Am J Pathol. 1984;116:253–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park KM, Kramers C, Vayssier-Taussat M, et al. Prevention of kidney ischemia/reperfusion-induced functional injury, MAPK and MAPK kinase activation, and inflammation by remote transient ureteral obstruction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2040–2049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen J, John R, Richardson JA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 regulates early endothelial activation during ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2011;79:288–299. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Greef KE, Ysebaert DK, Dauwe SE, et al. Anti-B7-1 blocks mononuclear cell adherence in vasa recta after ischemia. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1415–1427. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalis C, Kanzler B, Lembo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 expression levels determine the degree of LPS-susceptibility in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:798–805. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonventre JV, Weinberg JM. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2199–2210. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000079785.13922.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paller MS, Hoidal JR, Ferris TF. Oxygen free radicals in ischemic acute renal failure in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1156–1164. doi: 10.1172/JCI111524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nath KA, Norby SM. Reactive oxygen species and acute renal failure. Am J Med. 2000;109:665–678. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.di Mari JF, Davis R, Safirstein RL. MAPK activation determines renal epithelial cell survival during oxidative injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F195–F203. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.2.F195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C, Jackson RM. Reactive species mechanisms of cellular hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C227–C241. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00112.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arany I, Megyesi JK, Kaneto H, et al. Activation of ERK or inhibition of JNK ameliorates H2O2 cytotoxicity in mouse renal proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 2004;4:1231–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mollica L, De Marchis F, Spitaleri A, et al. Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem Biol. 2007;14:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Girard JP. A direct inhibitor of HMGB1 cytokine. Chem Biol. 2007;14:345–347. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, et al. Involvement of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bianchi ME. HMGB1 loves company. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:573–576. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1008585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hreggvidsdottir HS, Ostberg T, Wahamaa H, et al. The alarmin HMGB1 acts in synergy with endogenous and exogenous danger signals to promote inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:655–662. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petri B, Phillipson M, Kubes P. The physiology of leukocyte recruitment: an in vivo perspective. J Immunol. 2008;180:6439–6446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matzinger P. Friendly and dangerous signals: is the tissue in control? Nat Immunol. 2007;8:11–13. doi: 10.1038/ni0107-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rock KL, Latz E, Ontiveros F, et al. The sterile inflammatory response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:321–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mollen KP, Anand RJ, Tsung A, et al. Emerging paradigm: toll-like receptor 4-sentinel for the detection of tissue damage. Shock. 2006;26:430–437. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000228797.41044.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shigeoka AA, Holscher TD, King AJ, et al. TLR2 is constitutively expressed within the kidney and participates in ischemic renal injury through both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 2007;178:6252–6258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuo MC, Patschan D, Patschan S, et al. Ischemia-induced exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies mobilizes stem cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2321–2330. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yasuda H, Leelahavanichkul A, Tsunoda S, et al. Chloroquine and inhibition of Toll-like receptor 9 protect from sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1050–F1058. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00461.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, et al. A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11942–11947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003893107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li J, Gong Q, Zhong S, et al. Neutralization of the extracellular HMGB1 released by ischaemic damaged renal cells protects against renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;26:469–478. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu H, Ma J, Wang P, et al. HMGB1 Contributes to Kidney Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1878–1890. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009101048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wolfs TG, Buurman WA, van Schadewijk A, et al. In vivo expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 by renal epithelial cells: IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha mediated up-regulation during inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;168:1286–1293. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim BS, Lim SW, Li C, et al. Ischemia-reperfusion injury activates innate immunity in rat kidneys. Transplantation. 2005;79:1370–1377. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000158355.83327.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y, John R, Chen J, et al. IRF-1 promotes inflammation early after ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1544–1555. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thomas JA, Tsen MF, White DJ, et al. TLR4 inactivation and rBPI(21) block burn-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1645–H1655. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01107.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brunt LM, Portnoy DA, Unanue ER. Presentation of Listeria monocytogenes to CD8+ T cells requires secretion of hemolysin and intracellular bacterial growth. J Immunol. 1990;145:3540–3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaunitz JD, Cummins VP, Mishler D, et al. Inhibition of gentamicin uptake into cultured mouse proximal tubule epithelial cells by L-lysine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33:63–69. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Y, Woodward VK, Shelton JM, et al. Ischemia/ reperfusion induces G-CSF gene expression by renal medullary thick ascending limb cells in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1193–F1201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00379.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bookout AL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1508s73. Chapter 15: Unit 15.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thurman JM, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL, et al. Lack of a functional alternative complement pathway ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure in mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:1517–1523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.