Abstract

Objective To systematically review longitudinal studies evaluating use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and risk of pneumonia.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Medline through PubMed, Web of Science with conference proceedings (inception to June 2011), and US Food and Drug Administration website (June 2011). Systematic reviews and references of retrieved articles were also searched.

Study selection Two reviewers independently selected randomised controlled trials and cohort and case-control studies evaluating the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs and risk of pneumonia and retrieved characteristics of the studies and data estimates.

Data synthesis The primary outcome was incidence of pneumonia and the secondary outcome was pneumonia related mortality. Subgroup analyses were carried according to baseline morbidities (stroke, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease) and patients’ characteristics (Asian and non-Asian). Pooled estimates of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived by random effects meta-analysis. Adjusted frequentist indirect comparisons between ACE inhibitors and ARBs were estimated and combined with direct evidence whenever available. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 test.

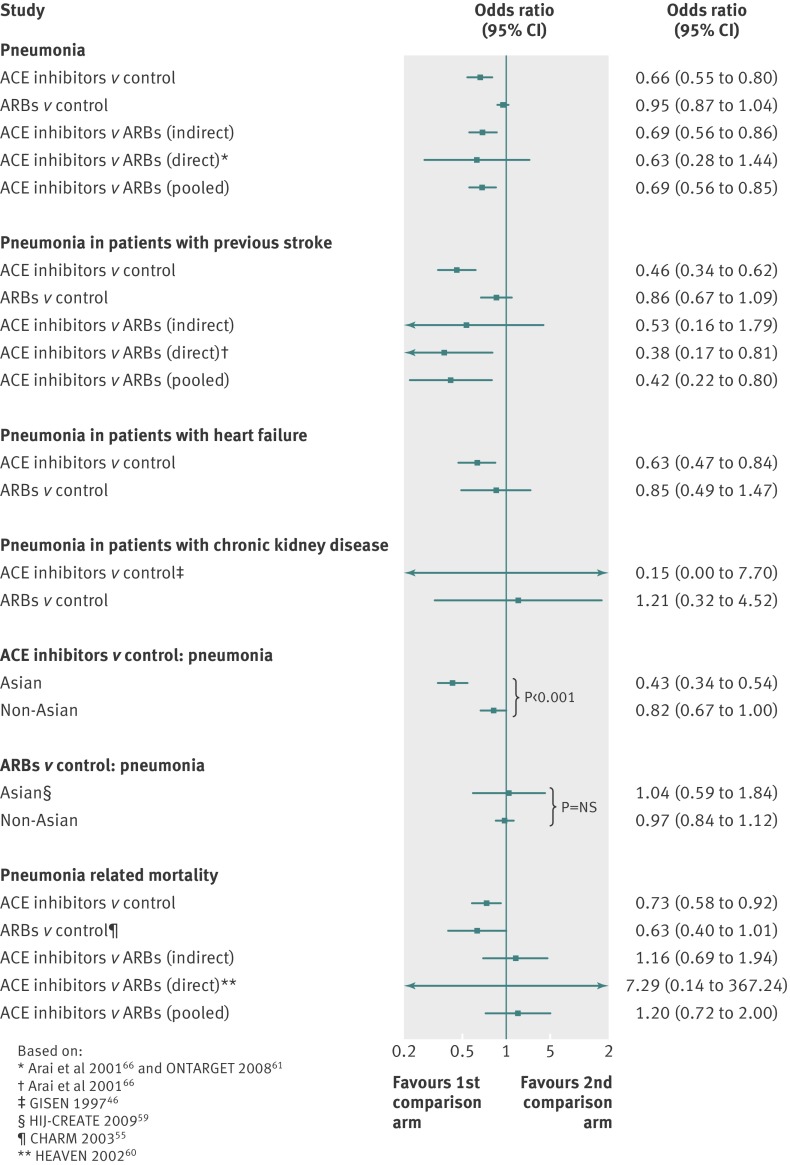

Results 37 eligible studies were included. ACE inhibitors were associated with a significantly reduced risk of pneumonia compared with control treatment (19 studies: odds ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.80; I2=79%) and ARBs (combined direct and indirect odds ratio estimate 0.69, 0.56 to 0.85). In patients with stroke, the risk of pneumonia was also lower in those treated with ACE inhibitors compared with control treatment (odds ratio 0.46, 0.34 to 0.62) and ARBs (0.42, 0.22 to 0.80). ACE inhibitors were associated with a significantly reduced risk of pneumonia among Asian patients (0.43, 0.34 to 0.54) compared with non-Asian patients (0.82, 0.67 to 1.00; P<0.001). Compared with control treatments, both ACE inhibitors (seven studies: odds ratio 0.73, 0.58 to 0.92; I2=51%) and ARBs (one randomised controlled trial: 0.63, 0.40 to 1.00) were associated with a decrease in pneumonia related mortality, without differences between interventions.

Conclusions The best evidence available points towards a putative protective role of ACE inhibitors but not ARBs in risk of pneumonia. Patient populations that may benefit most are those with previous stroke and Asian patients. ACE inhibitors were also associated with a decrease in pneumonia related mortality, but the data lacked strength.

Introduction

Pneumonia represents an important clinical condition because of its relatively high incidence (0.5% to 1.1% annually in the United Kingdom) and associated morbidity and mortality.1 2 Susceptibility is higher among elderly people (≥65 years), those with alcohol dependency, smokers, and patients with heart failure, previous stroke, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and chronic lung disease.3 4 5 6 Pneumonia is a common reason for hospital admission and a risk factor for prolonged hospital stay, carrying a considerable financial burden on healthcare resources.7 8

Usage of some drugs has been shown to modulate the risk of pneumonia. Acid suppressants can increase patients’ susceptibility to pneumonia, whereas statins may have a protective role.9 10 Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are often used in patients with cardiovascular disease. ACE inhibitors are known to have adverse effects on the respiratory system, in particular an increased incidence of cough. Basic investigation has shown that bradykinin and substance P sensitise the sensory nerves of the airways and enhance the cough reflex,11 12 13 which may have a protective role on the tracheobronchial tree.14 15 These mechanisms also improve swallowing by avoiding the exposure of the respiratory tree to oropharynx secretions.11 14 16 Taken together, the pleiotropic effects of ACE inhibitors were suggested to reduce the incidence of pneumonia, but available clinical evidence lacks strength17 18 19 and published results have been contradictory.20 21 22

We systematically reviewed and meta-analysed all studies (experimental and observational) evaluating the use of ACE inhibitors and incidence of pneumonia. Because the clinical characteristics and risk factors of populations using ARBs are similar to those of patients using ACE inhibitors, and therefore studies evaluating these interventions share identical potential clinical confounders, we also estimated the incidence of pneumonia in studies evaluating ARBs. Moreover, patients treated with ARBs are less likely to experience respiratory adverse events,23 24 and therefore ARBs may have a protective role.

Methods

The systematic review was carried out in accordance with the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology and preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statements.25 26

Our primary outcome was the incidence of pneumonia. We considered cases of pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infections, and admissions to hospital due to lower respiratory tract infections. Data were extracted irrespective of whether they had been reported as predefined outcomes or as adverse effects. If studies reported data for death from pneumonia only, to avoid duplication we did not consider these cases for the primary outcome. The secondary outcome was pneumonia related mortality, defined as death directly related to this condition or in-hospital death or mortality within 30 days after onset of pneumonia.27 For both outcomes, we did not consider undefined data or data on upper respiratory tract infections.

We considered randomised controlled parallel trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies with ACE inhibitors or ARBs as interventions and with predefined outcomes. Treatment arms could compare ACE inhibitors and ARBs with each other or with placebo or any other active drug. Cohort studies could be based on populations in the community or those in institutions or hospital and had to follow patients to determine pneumonia outcomes.

In case-control studies, cases had to be defined as patients with new onset pneumonia identified through clinical examination, radiological methods, or database codes. Controls had to be matched to cases, but without new onset pneumonia. For pneumonia related mortality, we allowed case-control studies with both cases and controls having pneumonia.

We allowed all participants, irrespective of baseline diseases and risk factors.

Information sources and search method

We identified potentially eligible studies through an electronic search of bibliographic databases from inception to June 2011 (Medline through PubMed and Web of Science with conference proceedings). See the supplementary file for details of the search strategy. No language restrictions were applied. We screened and cross checked identified systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating ACE inhibitors or ARBs, as well as reference lists of papers for potential additional studies. We also searched the Food and Drug Administration website (10 June 2011) for regulatory documents with unpublished data from clinical trials.

Study selection and data collection process

The titles and abstracts of obtained records were screened. Doubts and disagreements were resolved by consensus. We assessed the selected studies in full text to determine appropriateness for inclusion. Two authors independently extracted data on study design, location, period of study, patients’ characteristics, drug use and how it was assessed, primary outcomes, data of required outcomes, and adjustments of estimates.

When studies presented different estimates on primary outcomes according to the severity of pneumonia, we extracted for analysis only those reporting the most severe cases. For the primary outcome we considered drug withdrawals due to pneumonia only when no other estimates were available. When more than one risk estimate was available from several sources, we used only the most precise or adjusted measures of association from each report. Otherwise we used the crude odds ratio or derived it from the raw data.

Two authors (DC and JA) independently analysed the quality of reporting by using a qualitative classification according to risk of bias (high, unclear, or low). For observational studies we used a six item classification based on the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology,25 the quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies,28 and strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology.29 This system was adapted from a previously published systematic review30 31 and took into consideration the participants (if any justification was given for the cohort and the study reported appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria), intervention (if drug use was adequately assessed and not based on self report), outcome (if pneumonia was assessed by clinical examination, radiological methods, or database codes and not based on self report), and outcome adjustments (for both age and at least one of the following: smoker or pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases or drug use or chronic kidney disease; other adjustments). For randomised controlled trials we adapted the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias to evaluate the quality of reporting: randomisation method, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and staff, blinding of outcome assessment, selective reporting (if pneumonia was a prespecified outcome), and description of withdrawals.32 From these tools we derived risk of bias graphs.

Statistical analysis

We used RevMan 5.1.4 software for statistical analysis (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2011) and to derive forest plots showing the results of individual studies and pooled analysis.

We carried out three analyses. Firstly, we compared ACE inhibitors and ARBs with each control group using random effects meta-analysis weighted by the inverse variance method to estimate pooled odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 test, which measures the percentage of total variation between studies due to heterogeneity.33 We used the random effects model independently of the existence (I2≥50%) of substantial heterogeneity between the results of trials, as we pooled the results of studies with different designs and patients’ characteristics. We chose the odds ratio as the measurement estimate for effect because relative estimates are more similar than absolute effects across studies with different designs, populations, and lengths of follow-up.34 Raw data were first converted to odds ratios through classic methods, or through Peto’s method if one arm had a zero count cell. When raw data or odds ratios were not available we took the hazard ratio or risk ratio for analysis. To explore differences in estimates for outcomes we presented the results stratified according to study design. For the purpose of the analysis we treated nested case-control studies as cohort studies. We carried out subgroup analyses for patients with previous stroke, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease because such patients are known to be particularly susceptible to pneumonia and all indications are clinically approved for treatment with ACE inhibitors and ARBs.5 6 35 36 In view of the suggestion that ACE inhibitors may be more efficient in reducing the risk of pneumonia in Asian patients we also calculated estimates for Asian and non-Asian populations.37 We evaluated differences between subgroups with the method described by Deeks et al, based on the inverse variance method.33

In the second analysis we carried out adjusted indirect comparisons between the pooled estimate of ACE inhibitors (versus control) and ARBs (versus control) using the Bucher frequentist method, which compares different treatments adjusted to the results of their direct comparison with a common control.38 This method partially overcomes the problem of different prognostic characteristics between participants among studies, and it is believed to be valid assuming that the relative effect of interventions is consistent across different studies, as verified in our case.39 By default we used the random effects model because adjusted indirect comparisons that used the fixed effects model tend to underestimate the standard errors of pooled estimates.39

Thirdly, we combined evidence generated by indirect comparisons with evidence from head to head studies comparing ACE inhibitors with ARBs using the random effects model for quantitative pooling,40 41 and we determined the discrepancy and heterogeneity between direct and indirect estimates.42

We also calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and 95% confidence intervals, taking into account the baseline risk (weighted proportion of event rate in control group) because of the differences in the predicted absolute benefit of treatment according to variation in baseline risk between groups.34 43 In our case, the weighted risk of pneumonia in the control groups was 4.6% (95% confidence interval 3.1% to 6.7%). Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of the asymmetry in funnel plots.

Results

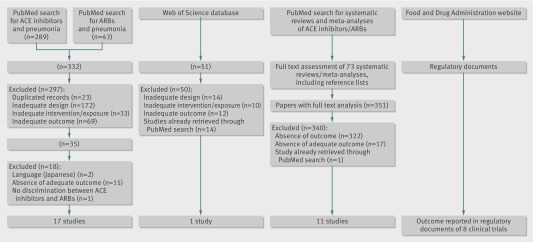

The search of the electronic databases yielded 807 published studies. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria 29 studies were included for analysis (fig 1). The results from eight additional studies were identified in the FDA regulatory documents. Overall, data were obtained from 37 studies.20 21 22 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79

Fig 1 Flow of studies through review. ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; ARBs=angiotensin receptor blockers

Description of studies

The 37 studies included 18 randomised controlled trials,20 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 11 cohort studies,62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 two nested case-control studies,21 74 and six case-control studies.22 75 76 77 78 79

Among randomised controlled trials, eight were done worldwide,47 48 51 52 55 57 58 61 six in Europe,44 45 46 53 56 60 three in Asia,49 50 59, and one in Europe and the United States.54 Most of the randomised controlled trials were multicentre (n=16). Seven randomised controlled trials compared ACE inhibitors with controls,44 45 46 47 48 49 50 nine compared ARBs with controls,51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 and two compared ACE inhibitors with ARBs.60 61 Seven trials reported specific data for serious pneumonia, five for fatal pneumonia, and eight reported pneumonia without specifying the severity of disease. In only two trials was pneumonia a prespecified outcome.49 59

Among observational studies, 10 were carried out in Asia, five in the United States, and four in Europe. Eleven studies were retrospective and eight were prospective. Seventeen evaluated ACE inhibitors, two ARBs, and two compared ACE inhibitors with ARBs.

Tables 1 to 3 summarise the main characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in review

| Study | Location | Mean follow-up (years) | Patients | Comparison | No (total) | Mean (SD) age | Primary outcome | Outcomes abstracted | Data* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors v control: | |||||||||

| CASSIS 199544 | Multicentre Czech Republic and Slovakia | 0.2 | Patients with chronic congestive heart failure | Spirapril or enalapril v placebo | 200 v 48 (248) | 57.5 (10) | Assessment of changes in exercise tolerance | Serious pneumonia† | Published |

| TRACE 199545 | Multicentre Denmark | 4.0 | Patients with left ventricular ejection fraction after myocardial infarction | Trandolapril v placebo | 876 v 873 (1749) | 67.5 | Death from any cause | Pneumonia† | Published |

| GISEN 199746 | Multicentre Italy | 1.3 | Patients with chronic nephropathy and persistent proteinuria | Ramipril v placebo | 78 v 88 (166) | 49.3 (13.6) | Rate of decline in glomerular filtration | Drug withdrawal due to bronchopneumonia† | Published |

| HOPE 200047 | Multicentre worldwide (not Asia) | 4.0 | Patients at high risk of developing a major cardiovascular event | Ramipril v placebo | 4645 v 4652 (9297) | 66 (7) | Myocardial infarction, stroke, or death due to cardiovascular disease | Serious pneumonia† | Unpublished |

| PROGRESS 200420 48 | Multicentre worldwide | 3.9 | Patients with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack | Perindopril v placebo | 3051 v 3054 (6105) | 64 (10) | Fatal or non-fatal stroke | Fatal and non-fatal pneumonia | Published |

| Kanda 200449 | Single centre Japan | 4.0 | Patients aged ≥65 with history of stroke and admitted with community acquired pneumonia | Imidapril+amantadine+standard care v standard care | 33 v 35 (68) | 78 (8) | In-hospital mortality, duration of antibiotic use, and infection with MRSA | Hospital death | Published |

| Hou 200650 | Single centre China | 3.4 | Patients with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease | Benazepril v placebo | 216 v112 (328) | 44.8 (14.6) | Composite of doubling of serum creatinine level, end stage renal disease, and death | Pneumonia as cause of mortality | Published |

| ARBs v control: | |||||||||

| Weber 199751 | Worldwide | 0.3 | Patients with essential hypertension and heart failure | Losartan v placebo | 125 v 29 | 54 | Adverse events | Pneumonia† | Published |

| IDNT 200152 | Multicentre worldwide | 4.8 | Patients with hypertension and with type 2 diabetes and overt proteinuria | Irbesartan v placebo or amlodipine | 579 v 569 (placebo) (1148) | 58.9 (7.8) | Time to first occurrence of doubling of baseline serum creatinine level, end stage renal disease, or death | Pulmonary infection† | Unpublished |

| IRMA-2 200153 | Multicentre Europe | 2.0 | Patients with hypertension and with type 2 diabetes, microalbuminuria, and normal renal function | Irbesartan 100 mg v irbesartan 300 mg v placebo | 389 v 201 (590) | 58.0 (8.1) | Time to occurrence of clinical overt albuminuria | Pulmonary infection† | Unpublished |

| LIFE 200254 | Multicentre Europe and USA | 4.8 | Patients with essential hypertension and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram | Losartan v atenolol | 4605 v 4588 (9193) | 66.9 (7.0) | Morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular disease | Pneumonia and serious pneumonia† | Published and unpublished |

| CHARM 200355 | Multicentre worldwide | 3.1 | Patients with symptomatic heart failure and reduced or preserved left ventricular ejection fraction | Candesartan v placebo | 3803 v 3796 (7599) | 66.6 (10.7) | All cause mortality | Serious pneumonia and death due to pneumonia† | Unpublished |

| MOSES 200556 | Multicentre Germany and Austria | 2.5 | High risk patients with hypertension and with cerebral event during past 24 months | Eprosartan v nitrendipine | 681 v 671 (1352) | 67.9 (10) | Total mortality and all cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events | Pneumonia† | Published |

| TRANSCEND 200857 | Multicentre worldwide | 4.8 | Patients with high risk of developing a cardiovascular event and who were intolerant to ACE inhibitors | Telmisartan v placebo | 2954 v 2972 (5926) | 66.9 (7.4) | Composite endpoint consisting of death due to cardiovascular disease, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and admission to hospital for congestive heart failure | Serious pneumonia† | Unpublished |

| PRoFESS 200858 | Multicentre worldwide | 2.0 | Patients with recent ischaemic stroke without treatment with ACE inhibitors | Telmisartan v placebo | 5589 v 5277 (10866) | 66.2 (8.6) | Time to first recurrent stroke | Serious pneumonia† | Unpublished |

| HIJ-CREATE 200959 | Multicentre Japan | 4.2 | Patients admitted to hospital with coronary artery disease and hypertension between 20 and 80 years old | Candesartan v non-ARB | 1024 v 1025 (2049) | 65 (9) | Time to first major adverse cardiovascular event | Pneumonia† | Published |

| ACE inhibitors v ARBs: | |||||||||

| HEAVEN 200260 | Sweden | 0.2 | Patients with stable mild or moderate heart failure and systolic dysfunction | Enalapril v valsartan | 71 v 70 (141) | 68 | Exercise capacity measured as distance walked during six minute walk test | Death due to pneumonia | Published |

| ONTARGET 200861 | Multicentre worldwide | 4.6 | Patients at high risk of developing major cardiovascular event | Ramipril v telmisartan v telmisartan+ramipril | 8576 (ramipril) v 8542 (telmisartan) (17118) | 66.4 | Time to first occurrence of either death due cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, or admission to hospital for congestive heart failure | Serious pneumonia† | Unpublished |

ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; MRSA=meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

*Data for unpublished articles were obtained from FDA regulatory documents.

†Adverse event.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of cohort studies included in review

| Study | Location, study design | Study length (years) | Data source; period of study | Patients | Comparison | No (total) | Mean (SD) age | Outcome measures | Ascertainment | Outcome adjustments for confounders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug use | Outcomes | ||||||||||

| Sekizawa 199862 | Japan, prospective (patients in long term facilities) | 2.5 | March 1996-98 | Patients with stroke treated with hypertensive drugs | Imidapril, enalapril or captopril v CCB or β blocker | 127 v 313 (440) | 77 (8) | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Teramoto 199963 | Japan, retrospective | 4.0 | 1995-98 | Outpatients with hypertension | ACE inhibitor v CCB v ACE inhibitor+CCB | 234 (ACE inhibitor) v 264 (CCB) (498) | NR | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Arai 200064 and Arai 199865 | Japan, prospective | 4.0 | January 1995-December 1999 | Elderly patients with hypertension | Imidapril v CCB | 466 v 413 (879) | 75.9 | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Arai 200166 | Japan, prospective | 2.0 | January 1998-May 2002 | Elderly patients with hypertension and stroke | ACE inhibitor v ARB | 209 v 195 (404) | NR | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Arai 200567 | Japan, prospective | 3.0 | April 1999-2002 | Patients with stroke who were not bedridden and were followed for >6 months after stroke | ACE inhibitor v CCB v diuretics v control | 430 v 409 v 351 v 160 (1350) | 75 (1) | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Mortensen 200568 | USA, retrospective (hospital based cohort) | 4.0 | Texas Department of Health and Department of Veteran Affairs clinical database; January 1999-December 2002 | Patients with primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia or secondary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia with primary diagnosis of respiratory failure or sepsis | ACE inhibitor v control | 194 v 593 (787) | 60 (16) | 30 day mortality | Self reporting and electronic medical records | ICD-9 codes | Pneumonia severity and history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus |

| Harada 200669 | Japan, prospective | 2.0 | 2 years | Elderly patients admitted to hospital with intracerebral haemorrhage | ACE inhibitor v control | 22 v 61 (83) | 68 (2) | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

| Mortensen 200870 | USA, retrospective | 1 year | National patient care database from Austin Automation Center; July 1999-January 2000 | Elderly patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia | ACE inhibitor v control | 2930 v 5722 (8652) | 75.2 (6.1) | 30 day mortality | Assessed from beneficiary identification records locator subsystem and national patient care database | Pharmacy data from Pharmacy Benefits Management group databases | Age, sex, marital status, classes of drugs, and Charlson composite score |

| Chalmers 200871 | UK, prospective (community based cohort) | 3 years | NHS Lothian University Hospitals Division January 2005-November 2007 | Patients with community acquired pneumonia | ACE inhibitor or ARB v control | 136/31 v 871 (1038) | 66 | 30 day mortality | Self report of drugs confirmed with general practitioner after admission | NR | Age, pneumonia severity, comorbidity, smoking status, and other cardiovascular drugs |

| Myles 200972 | UK, retrospective (population based cohort) | 2.8 | The Health Improvement Network database; July 2001-July 2005 | Patients with pneumonia | ACE inhibitor v control | 795 v 2886 (3681) | >40 | 30 day mortality | Data extracted from all recorded prescriptions within 30 days from pneumonia index date | ICD-9 codes | Age, sex, Townsend deprivation score, current smoking, Charlson comorbidity index, and other use of drugs |

| Cuifang 201073 | China, prospective | NR | NR | Patients with hypertension and stroke | ACE inhibitor v control | 147 v 342 (489) | >60 | Pneumonia | NR | NR | NR |

CCB=calcium channel blockers; ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; NR=not reported.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of case-control studies included in review

| Study | Location, study design | Data length (years) | Data source; period of study | Patients | Matching | ACE inhibitor or ARB | No with pneumonia v controls (total) | Mean (SD) age | Outcome | Ascertainment | Outcome adjustments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug use | Outcome | |||||||||||

| Nested case-control studies: | ||||||||||||

| Etminan 200621 | Canada, retrospective | 5.0 | Databases of administrative healthcare programmes offered to residents of Quebec; 1996-2000 | Patients who went for coronary revascularisation procedure and had incident pneumonia after hospital discharge | Ratio 1:20; time of follow-up, same calendar year of cohort entry, and age | NR | 1666 v 33315 (47 148) | 71 (8.3) | Admitted to hospital with pneumonia | Database records | ICD-9 codes | Sex, comorbidities, previous heart failure, number of physician visits, and drugs used |

| Mukamal 201074 | USA, Puerto Rico, and US Virgin Islands, retrospective | 7.0 | Data on adults with hypertension insured by large commercial plans; January 2000-November 2007 | Patients with hypertension and incident pneumonia | Ratio 1:10; age, sex, residence, insurance plan, subscriber status, and date of enrolment | NR | 7429 v 73571 (81 000) | 58.2 (12.7) | Pneumonia | Records of filled pharmacy claims | ICD-9 codes | Diabetes, inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, organ transplantation, and drugs used |

| Case-control studies: | ||||||||||||

| Okaishi 199975 | Japan, prospective18 (hospital-based study) | 1.0 | Department of Internal Medicine of Hanwa-Senbooku Hospital; July 1996-June 1997 | Patients aged ≥65 years with fatal or non-fatal pneumonia | Ratio 1:4; sex and age | Temocapril, alacepril, cilazapril, captopril | 55 v 220 (275) | 81.1 (7.7) | Admission for pneumonia | Hospital computerised pharmacy database | Personal physicians. Questionable events reviewed by physician blinded to patients’ drugs | Age, sex, dementia, hypoalbuminemia, bedridden state, lung disease, and antacid use |

| El Solh 200476 | USA, retrospective | 4.0 | Electronic database from 3 tertiary care hospitals; March 1999-August 2003 | Patients aged >65 years readmitted to hospital with pneumonia over 1 year from first episode | Ratio 1:1; age, admission date, and residence | NR | 204 v 204 (408) | 78.5 (8.2) | Hospital admission for pneumonia | Database records | Database records | Multivariate, not defined |

| Takahashi 200577 | Japan, retrospective (hospital based study) | 0.7 | April 1999-November 1999 | Patients with admission period >3 months who presented with fatal or non-fatal pneumonia | Ratio 1:4; sex and age | Temocapril | 105 v 420 (525) | 82.8 (8) | Pneumonia | Hospital computerised pharmacy database | Information collected by full time nurses under physicians’ supervision. Questionable events were reviewed by physician without knowledge of patients’ drugs | Age, sex, bedridden state, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, ACE polymorphism, and use of other antihypertensives |

| Van de Garde 200622 | Netherlands, retrospective (population based study) | 6.0 | PHARMO record linkage system and PRISMANT records; January 1995-December 2000 | Patients admitted to hospital with primary diagnosis of pneumonia | Ratio 1:4; age and sex | NR | 1108 v 3817 (4925) | 67 (0.51) | Hospital admission for community acquired pneumonia | ATC classification | ICD-9 codes | Diabetes, respiratory diseases, heart failure, use of systemic corticosteroids, and use of gastric acid suppressants |

| Van de Garde 200778 | UK, retrospective | 14.0 | UK General Practice Research Database; June 1987-January 2001 | Patients with diabetes who had first diagnosis of pneumonia | Ratio 1:4; age, sex, type of stroke, NIH Stroke Scale score, side and depth of stroke | Cilazapril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril, trandolapril | 4719 v 15 332 (20 041) | 73 (11) | Pneumonia | Receipt of prescriptions within year before index date | Codes of Oxford Medical Information System | Age, congestive heart failure, history of stroke, evident alcohol misuse, pulmonary diseases, smoking, number of general practitioner visits a year, oral glucocorticoid use, statin use, pneumococcal vaccination, and use of gastric acid suppressants |

| Marciniak 200979 | USA, retrospective | 4.0 | Stroke rehabilitation registry database, September 1999-August 2003 | Patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation within 90 days after stroke onset who developed pneumonia | NR | NR | 36 v 36 (72) | 66.3 (12.1) | Pneumonia | Medical records | Medical records, chest radiography confirmation | Presence of tracheostomy or feeding tube |

ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; NR=not reported; ATC=anatomical therapeutic chemical system.

The overall quality of the studies was considered to be good. All the randomised controlled trials, except one,51 met the criteria for random sequence generation and about half specifically reported adequate allocation concealment.46 48 50 54 55 57 58 61 Only two randomised controlled trials56 59 were considered to be at high risk of performance bias. Adequate blinding of outcome assessment45 46 47 48 50 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 61 and full description of study withdrawals44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 57 58 60 61 were reported in 78% and 89% of randomised controlled trials, respectively. The highest risk of bias was found for potential reporting bias because only two randomised controlled trials presented results for pneumonia as a prespecified outcome.49 59 Supplementary figures 1 and 2 show the results of the quality appraisal of the randomised controlled trials.

All observational studies were considered to have adequate inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided justification for the cohort. Five studies (26%)62 63 64 66 69 did not clearly stated how the drug use was assessed, and four studies (21%)63 64 66 73 did not provide details about outcome assessment. Eleven studies (58%)21 22 68 70 71 72 74 75 77 79 provided results after adjustment for at least one potential variable confounder. In one study76 it was unclear for which variables the results were adjusted. Few studies (26%) reported results adjusted for multiple confounders, and in seven studies (37%) no type of adjustment was mentioned. Supplementary figures 3 and 4 show the results for the quality of the observational studies.

Primary outcome: incidence of pneumonia

Primary outcome data were available from 19 studies comparing ACE inhibitors with controls (five randomised controlled trials, eight cohort or nested case-control studies, and six case-control studies), 11 studies comparing ARBs with controls (nine randomised controlled trials and two cohort or nested case-control studies), and two studies comparing ACE inhibitors with ARBs (one randomised controlled trial and one cohort study).

Use of ACE inhibitors was associated with a significant 34% reduction in risk of pneumonia compared with controls (odds ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.80; I2=79%). The NNT for 2.0 years was 65 (48 to 112). The magnitude of the risk reduction was similar across all study designs (P=0.78 for subgroup differences). The odds ratios for randomised controlled trials, cohort or nested case-control studies, and case-control studies were 0.69 (0.56 to 0.85; I2=0%), 0.58 (0.38 to 0.88; I2=79%), and 0.67 (0.49 to 0.93; I2=73%), respectively (fig 2).

Fig 2 Risk of pneumonia with use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors compared with control treatment

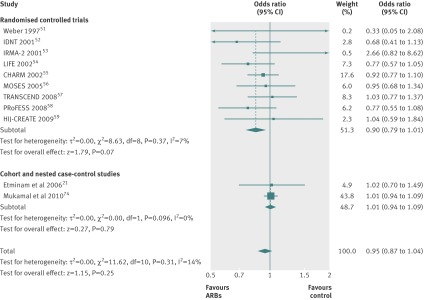

The risk of pneumonia was not, however, different between patients who did or did not use ARBs (0.95, 0.87 to 1.04; I2=14%). Odds ratio estimates for randomised controlled trials (0.90, 0.79 to 1.01; I2=7%) and cohort or nested case-control studies (1.01, 0.94 to 1.09; I2=0%) did not differ significantly (P=0.10; fig 3).

Fig 3 Risk of pneumonia with use of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) compared with control treatment

Pooled results from the two head to head studies showed a non-significant 37% reduction in risk of pneumonia associated with use of ACE inhibitors (0.63, 0.28 to 1.44; I2=78%). In this case, estimates from the randomised controlled trial and cohort study differed significantly (P=0.03) (see supplementary figure 5).

Indirect comparison of ACE inhibitors with ARBs showed a significant 30% reduction in risk of pneumonia associated with use of ACE inhibitors (0.70, 0.56 to 0.86). Similar results were obtained from pooled direct and indirect estimates (0.69, 0.56 to 0.85) without discrepancy (P=0.82) or heterogeneity (I2=0%) between both estimates (fig 4). The NNT for 2.2 years based on this estimate was 72 (51 to 147).

Fig 4 Summary of meta-analysis estimates and subgroup analyses. ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; ARBs=angiotensin receptor blockers

Subgroup analyses for primary outcome

Patients with previous stroke

In patients with previous stroke, use of ACE inhibitors was associated with a 54% reduction in risk of pneumonia compared with controls (0.46, 0.34 to 0.62, I2=0%; seven studies pooled) (see supplementary figure 6). In the same population, however, use of ARBs was not associated with a significant reduction in risk (0.86, 0.67 to 1.09; I2=0%; two studies pooled) (see supplementary figure 7).

The pooled estimate from indirect (odds ratio 0.53, 95% confidence interval 0.16 to 1.79) and direct (0.38, 0.17 to 0.81) evidence of ACE inhibitors compared with ARBs showed a significant 58% reduction in risk of pneumonia (0.42, 0.22 to 0.80; fig 4), without discrepancy (P=0.44) or heterogeneity (I2=0%) between indirect and direct estimates.

Patients with heart failure

In patients with heart failure, two studies evaluated the risk of pneumonia in those treated with ACE inhibitors44 45 and two other studies reported data for those treated with ARBs.51 52 ACE inhibitors were associated with a significant 37% reduction in risk of pneumonia (0.63, 0.47 to 0.84; I2=0%), whereas ARBs showed no significant effect (0.85, 0.49 to 1.47; I2=15%) (see supplementary figure 8).

Patients with chronic kidney disease

In patients with chronic kidney disease, the results from one randomised controlled trial of ACE inhibitors46 (odds ratio 0.15, 95% confidence interval 0.00 to 7.70) and two randomised controlled trials of ARBs52 53 (1.21, 0.32 to 4.52; I2=77%) did not differ significantly when compared with controls (see supplementary figure 9).

Asian and non-Asian patients

Eleven studies were carried out in Asian countries and 11 were done outside of Asia. The PROGRESS20 study was the only multicentre study carried out worldwide that supplied separate data for Asian and non-Asian patients. To lower analysis bias, the other studies carried out worldwide that did not provide separate data for both groups were excluded.

The reduction in risk of pneumonia associated with ACE inhibitors was significantly higher among Asian patients (0.43, 0.34 to 0.54; I2=0%) compared with non-Asian patients (0.82, 0.67 to 1.00, I2=80%, P<0.001 for subgroup differences) (see supplementary figure 10). ARBs, however, were not associated with a reduction in risk of pneumonia in Asian patients (1.04, 0.59 to 1.84; one randomised controlled trial HIJ-CREATE59) or non-Asian patients (0.97, 0.84 to 1.12; I2=27%; five studies pooled; fig 4 and supplementary figure 11).

Secondary outcome: pneumonia related mortality

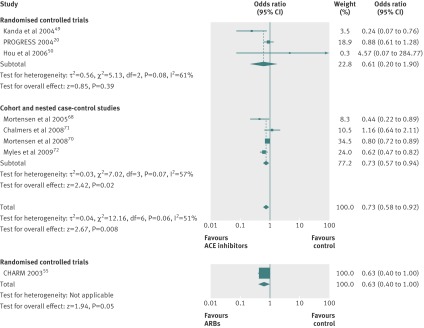

Data for secondary outcomes were extracted from seven studies comparing ACE inhibitors with controls (three randomised controlled trials and four cohort studies),20 49 50 68 70 71 72 one randomised controlled trial comparing ARBs with control,55 and one head to head randomised controlled trial.60 Five studies comparing ACE inhibitors with controls were carried out on an enriched population—that is, enrolled patients with pneumonia.49 68 70 71 72

Treatment with ACE inhibitors was associated with a significant 27% reduction in risk of pneumonia related mortality compared with controls (0.73, 0.58 to 0.92; I2=51%), without significant differences between estimates from randomised controlled trials and observational studies (P=0.76). The pooled result from randomised controlled trials, however, failed to reach statistical significance (0.61, 0.20 to 1.90; I2=61%) (fig 5).

Fig 5 Pneumonia related mortality in studies comparing angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) with control treatment

Only one randomised controlled trial55 reported the effect of treatment with ARBs on pneumonia related mortality (odds ratio 0.63, 95% confidence interval 0.40 to 1.00) (fig 5).

The risk of pneumonia related mortality in indirect (1.16, 0.69 to 1.94), direct (HEAVEN randomised controlled trial60 7.29, 0.14 to 367.24), and pooled comparisons (1.19, 0.71 to 1.98) did not differ between ACE inhibitors and ARBs (fig 4). There was no discrepancy (P=0.36) or heterogeneity (I2=0%) between indirect and direct estimates.

Publication bias

Visual inspection of funnel plots did not reveal any obvious asymmetrical tail (see supplementary figure 12). Publication bias was not suggested by sensitivity analysis taking into account published and unpublished trials (see supplementary figure 13).

Discussion

In this systematic review we found that treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors was associated with a significant reduction in risk of pneumonia compared with control treatment and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs); the magnitude of this reduction (about one third) was similar across studies with different designs (randomised controlled trials, cohort, and case-control studies). The risk of pneumonia was also reduced in patients treated with ACE inhibitors who were at higher risk of pneumonia, in particular those with stroke and heart failure. Most of the potential protective benefit from ACE inhibitors seemed to be in Asian patients; it is unclear whether the methodology of the studies or the clinical and genetic characteristics of the patients were responsible for this finding. Use of ACE inhibitors was also associated with a reduction in pneumonia related mortality, although the results were less robust than for overall risk of pneumonia; it is uncertain if differences exist between ACE inhibitors and ARBs for this outcome.

The present review was designed to determine the effect of treatment with ACE inhibitors and ARBs on risk of pneumonia. We combined data from both experimental and observational studies to obtain more robust results, mainly because no randomised controlled trial was primarily designed with this objective. Pneumonia is not a rare outcome (particularly in populations treated with ACE inhibitors or ARBs) or an outcome that only occurs months to years after use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Therefore randomised controlled trials would have been an appropriate study design to deal with this problem. We found significant statistical heterogeneity for ACE inhibitors but not for ARB results. This was due to the results of observational studies (no heterogeneity was found among randomised controlled trials). Nevertheless, the observed statistical heterogeneity was more quantitative than qualitative because all estimates for study designs share the same direction. This consistency, as well as the robustness of reduction in the risk of pneumonia across all study designs, suggests that use of ACE inhibitors deserves attention. Furthermore, that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of pneumonia compared not only with the control group but also with ARB treatment, is reassuring because patients’ characteristics and risk factors, as well as other potential clinical and methodological confounders are probably similar between studies on ARBs and those on ACE inhibitors. We were also conservative in our analysis because we did not consider undefined data or data on upper respiratory tract infections, and when studies presented different estimates according to the severity of pneumonia we extracted those reporting only the most severe cases and the most precise or adjusted measure.

Our findings have potential clinical implications. ACE inhibitors are widely prescribed and prescriptions may be influenced by concerns about potential adverse effects, in particular cough, which may be protective. The incidence of ACE inhibitor induced cough has been reported to be in the range of 5% to 35%.80 Our results suggest that patients taking ACE inhibitors who develop cough should, providing that cough is tolerable, persist with treatment. Compliance and persistence with treatment is important. Furthermore, from an evidence based perspective, there is little to choose between ACE inhibitors and the more expensive ARBs. However, in the case of a particular patient, in whom ACE inhibitors and ARBs are presumed to have similar clinical benefit, our results may also influence the choice of prescription in those at high risk of pneumonia. Therefore patients with risk factors for pneumonia and morbidities that require treatment with ACE inhibitors may have an additional reason to continue treatment.

A further important aspect of our results was the reduction in risk of pneumonia across high risk patients, which provided consistency to the overall results. Patients with previous stroke have increased susceptibility to pneumonia owing to risk of aspiration associated with decreased protective reflexes of the respiratory system mediated by substance P and post-stroke dysphagia.14 81 About 20% of these patients will develop pneumonia,82 which is a predictor of poor functional outcome83 84 and a relevant cause of death.84 85 The putative protective effect of ACE inhibitors in this population was predictable given the importance of dysphagia and substance P in these patients. According to one study, ARBs do not increase the levels of substance P or improve asymptomatic dysphagia.86 This highlights the importance of using ACE inhibitors in patients with previous stroke who have comorbidities for which ACE inhibitors are recommended.

Only a few studies evaluated other populations with increased risk, such as patients with heart failure or chronic kidney disease. For patients with heart failure, the decreased risk of pneumonia was also found in patients treated with ACE inhibitors. The suggested effect was significant but this evaluation lacked robust data. ARBs did not show any protective effect.

The putative preventive effect of ACE inhibitors on pneumonia in Asian patients has been suggested.37 We explored this subgroup and compared the effect with non-Asian patients. Furthermore, we obtained a considerable weight of evidence from studies that evaluated Asian patients. ACE inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of pneumonia in both Asian and non-Asian patients, although the odds reduction was significantly higher in Asian patients (57% v 12%; P<0.001). ARBs did not reduce the risk of pneumonia in either population.

Genetic differences in ACE polymorphisms between Asian and non-Asian patients have been suggested to explain the difference in protective effects. Polymorphisms I/I and I/D, which are more prevalent in Asian population, showed a protective trend in the post-hoc analysis in PROGRESS, whereas the D/D polymorphism was less protective.20 77 87 This last polymorphism is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome, particularly in white populations.88 This potential loss of protective effect may be explained by increased levels of serum ACE inhibitors and catabolism of kinins in patients with the D/D polymorphism.89 However, genetic evidence is equivocal. One study did not find an association between any specific genotype and pneumonia.90 Other factors should be explored to explain these differences in ethnic groups or by geographical location to better define those who can benefit more.

Our conclusions are weaker for pneumonia related mortality because fewer studies provided data for this outcome and significant heterogeneity existed for the results of ACE inhibitors. This uncertainty was reflected by the wider confidence intervals. Treatment with ACE inhibitors (three randomised controlled trials and four cohort studies) and ARBs (one randomised controlled trial) were both associated with a decreased risk of pneumonia related mortality. Explanations for such findings may rely on modulation of cardiovascular risk by ACE inhibitors and ARBs because deaths due to cardiovascular disease are not uncommon among patients with pneumonia.27 91 Decreased mortality may also be explained by the role of ACE inhibitors in pulmonary injury and production of cytokines, which may be related to severity of pneumonia.92 93 94 ACE inhibitors may influence the pattern for release of cytokines exerting anti-inflammatory effects that could reduce the severity of and mortality from pneumonia.95

The influence of ACE inhibitors on survival in these patients should be interpreted carefully because observational studies with enriched populations accounted for most of the weight of the pooled analysis, whereas meta-analysis of three randomised controlled trials (one with an enriched population) did not show differences between ACE inhibitors and controls. However, there was no significant difference in effects between overall randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Although the data were not robust, they did suggest that the effects of treatment with ACE inhibitors on mortality were mostly noticeable in patients with pneumonia.

Limitations of the review

The results and conclusion of this review are weakened by limitations inherent to meta-analysis and individual studies. The overall quality of included studies was good. However, reporting quality for a few studies, particularly observational ones, was low as some of these were abstracted from character limited sections such as letters or comments.

The higher risk of bias was found for potential selective reporting in randomised controlled trials and presentation of unadjusted risk estimates in observational studies. Both limit the strength of our conclusions. A key limitation is that not one randomised controlled trial was primarily designed to assess the effects of ACE inhibitors or ARBs on pneumonia. Although we searched a large number of studies, only a few reported this outcome. Among these, only two randomised controlled trials (<25%) had pneumonia or pneumonia related mortality as a predefined outcome.49 59 As a consequence we were able to extract data only from studies where authors considered pneumonia to be an important outcome, because of either scientific interest or statistical significance.

Observational studies had an important weight in the results for the primary outcome and this should be taken into account when interpreting the clinical implications of our findings. Use of cardiovascular drugs in observational studies could bias results, because patients using drugs could be more concerned for their health and more willing to follow medical advice than controls, the so-called healthy user effect bias.96 However, patients with pneumonia are likely to have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease91 97 and are more likely to be treated with ACE inhibitors, counterbalancing the bias from a healthy user effect. Additionally, the magnitude of the odds risk reduction was similar for randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies.

Pooling data from studies with different designs (confounding bias in observational studies) that evaluated patients in different settings (community based and hospital based studies; referral bias), as well as with different baseline morbidities and heterogeneous risk (membership bias) for pneumonia, should also be taken into account as limitations to our conclusions. The degree of statistical heterogeneity was in fact high in some comparisons. Nevertheless, the pooled estimates from experimental and observational studies were similar. In this case, pooling experimental and observational data increased the power and external validity of the findings.

Included studies compared different ACE inhibitors and ARBs with different controls, such as placebo, calcium channel blockers, and β blockers. In the present analysis we did not carry out serial subgroup analysis to explore if the effect was different for a particular drug because of the scarcity of the data and the risk of obtaining a result by chance.

Finally, we used adjusted indirect comparisons to estimate the effect of ACE inhibitors compared with ARBs. Although combined indirect and direct evidence showed no discrepancies or heterogeneity, the results should not be thought as definitive conclusions because of the possibility of imbalanced data from studies with different designs, baseline risk of patients, and length of follow-up.

Conclusions

Our results suggest an important role of ACE inhibitors, but not ARBs, in reducing the risk of pneumonia. These data may discourage the withdrawal of ACE inhibitors in some patients with tolerable adverse events (namely, cough) who are at particularly high risk of pneumonia. Specific designed randomised controlled trials are required to establish definite conclusions and to estimate better the true magnitude of this putative protective effect. Patients with previous stroke and Asian patients are patient populations that could benefit more from treatment with ACE inhibitors. ACE inhibitors also lowered the risk of pneumonia related mortality, mainly in patients with established disease, but the robustness of the evidence was weaker.

What is already known on this topic

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease

These drugs also have secondary effects on the respiratory system, suggested to protect against pneumonia

Most of the data on this issue are provided by heterogeneous observational studies with inconclusive results

What this study adds

In pooled results from both interventional and observational studies, ACE inhibitors, but not angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), showed a statistical and putative clinically significant protective role against pneumonia

This result may discourage the withdrawal of ACE inhibitors in patients with tolerable adverse events—namely, cough

This protective effect was higher among Asian patients and in those with previous stroke; patient populations that may benefit most from ACE inhibitors

We thank the Cochrane Coordinating Centre in Portugal.

Contributors: DC and JA contributed to the concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation of the data; wrote the first draft of the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. AVC contributed to the interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. JC contributed to the concept and design, data analysis, and interpretation of the data; wrote the first draft of the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; and gave final approval of the submitted manuscript. JC is the guarantor.

Funding: This was an academic project not funded by government or non-government grants.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e4260

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Search strategy

Supplementary figures 1-13

References

- 1.File TM. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2003;362:1991-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, Hill AT, Jamieson C, Le Jeune I, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009;64(suppl 3):iii,1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samokhvalov AV, Irving HM, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:1789-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Balanzó X, González CA. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study. Eur Respir J 1999;13:349-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinogradova Y, Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Identification of new risk factors for pneumonia: population-based case-control study. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:e329-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung HB, Monteagudo-Chu MO. Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:47-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HC, Chang KC, Lan CF, Hong CT, Huang YC, Chang ML. Factors associated with prolonged hospital stay for acute stroke in Taiwan. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2008;17:17-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metersky ML, Tate JP, Fine MJ, Petrillo MK, Meehan TP. Temporal trends in outcomes of older patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3385-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, Cho EG, Park SM, Lee KS. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2011;183:310-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tleyjeh IM, Kashour T, Hakim FA, Zimmerman VA, Erwin PJ, Sutton AJ, et al. Statins for the prevention and treatment of infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1658-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morice AH, Lowry R, Brown MJ, Higenbottam T. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and the cough reflex. Lancet 198;2:1116-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fox AJ, Lalloo UG, Belvisi MG, Bernareggi M, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Bradykinin-evoked sensitization of airway sensory nerves: a mechanism for ACE-inhibitor cough. Nat Med 1996;2:814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomaki M, Ichinose M, Miura M, Hirayama Y, Kageyama N, Yamauchi H, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-induced cough and substance P. Thorax 1996;51:199-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekizawa K, Ujiie Y, Itabashi S, Sasaki H, Takishima T. Lack of cough reflex in aspiration pneumonia. Lancet 1990;335:1228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontoppidan H, Beecher HK. Progressive loss of protective reflexes in the airway with the advance of age. JAMA 1960;174:2209-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama K, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. ACE inhibitor and swallowing reflex. Chest 1998;113:1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Solh AA, Saliba R. Pharmacologic prevention of aspiration pneumonia: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007;5:352-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafailidis PI, Matthaiou DK, Varbobitis I, Falagas ME. Use of ACE inhibitors and risk of community-acquired pneumonia: a review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:565-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siempos II, Vardakas KZ, Kopterides P, Falagas ME. Adjunctive therapies for community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:661-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohkubo T, Chapman N, Neal B, Woodward M, Omae T, Chalmers J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-based regimen on pneumonia risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:1041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etminan M, Zhang B, Fitzgerald M, Brophy JM. Do angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers decrease the risk of hospitalization secondary to community-acquired pneumonia? A nested case-control study. Pharmacotherapy 2006;26:479-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Garde EM, Souverein PC, van den Bosch JM, Deneer V H, Leufkens HG. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use and pneumonia risk in a general population. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1217-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickstein K, Kjekshus J; OPTIMAAL Steering Committee of the OPTIMAAL Study Group. Effects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Optimal Trial in Myocardial Infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan. Lancet 2002;360:752-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Køber L, Maggioni AP, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1893-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, Marrie TJ, Obrosky DS, Kapoor WN, et al. Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1059-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong WC, Cheung CS, Hart GJ. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2008;5:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 2007;18:800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter P, Gray LJ, Troughton J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buitrago-Lopez A, Sanderson J, Johnson L, Warnakula S, Wood A, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Chocolate consumption and cardiometabolic disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;343:d4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 33.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in metaanalysis. In Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. BMJ Publishing Group, 2001:313-35.

- 34.Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med 2002;21:1575-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Arai H, Kikuchi R, Manabe K, Sasaki H. High incidence of pneumonia in elderly patients with basal ganglia infarction. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:321-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Nakajoh K, Tanji H, Arai H, Sasaki H. Silent cerebral infarction: a potential risk for pneumonia in the elderly. J Intern Med 2000;247:255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teramoto S, Yamamoto H, Yamaguchi Y, Hanaoka Y, Ishii M, Hibi S, et al. ACE inhibitors prevent aspiration pneumonia in Asian, but not Caucasian, elderly patients with stroke. Eur Respir J 2007;29:218-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;326:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, Sakarovitch C, Deeks JJ, D’Amico R, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-134,iii-iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song F, Harvey I, Lilford R. Adjusted indirect comparison may be less biased than direct comparison for evaluating new pharmaceutical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:455-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smeeth L, Haines A, Ebrahim S. Numbers needed to treat derived from meta-analyses—sometimes informative, usually misleading. BMJ 1999;318:1548-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Widimský J, Kremer HJ, Jerie P, Uhlír O. Czech and Slovak spirapril intervention study (CASSIS). A randomized, placebo and active-controlled, double-blind multicentre trial in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1995;49:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, Bagger H, Eliasen P, Lyngborg K, et al. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Lancet 1997;349:1857-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000;342:145-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001;358:1033-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanda A, Ebihara S, Yasuda H, Takashi O, Sasaki T, Sasaki H. A combinatorial therapy for pneumonia in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:846-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou FF, Zhang X, Zhang GH, Xie D, Chen PY, Zhang WR, et al. Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2006;354:131-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber M. Clinical safety and tolerability of losartan. Clin Ther 1997;19:604-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:851-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002;359:995-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, et al. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 2003;362:759-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schrader J, Lüders S, Kulschewski A, Hammersen F, Plate K, Berger J, et al. Morbidity and mortality after stroke, eprosartan compared with nitrendipine for secondary prevention: principal results of a prospective randomized controlled study (MOSES). Stroke 2005;36:1218-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators: Yusuf S, Teo K, Anderson C, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1174-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yusuf S, Diener HC, Sacco RL, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, et al. Telmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1225-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kasanuki H, Hagiwara N, Hosoda S, Sumiyoshi T, Honda T, Haze K, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blocker-based vs non-angiotensin II receptor blocker-based therapy in patients with angiographically documented coronary artery disease and hypertension: the Heart Institute of Japan Candesartan Randomized Trial for Evaluation in Coronary Artery Disease (HIJ-CREATE). Eur Heart J 2009;30:1203-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willenheimer R, Helmers C, Pantev E, Rydberg E, Löfdahl P, Gordon A, et al. Safety and efficacy of valsartan versus enalapril in heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol 2002;85:261-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.ONTARGET Investigators: Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, Schumacher H, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sekizawa K, Matsui T, Nakagawa T, Nakayama K, Sasaki H. ACE inhibitors and pneumonia. Lancet 1998;352:1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teramoto S, Ouchi Y. ACE inhibitors and prevention of aspiration pneumonia in elderly hypertensives. Lancet 1999;353:843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arai T, Yasuda Y, Takaya T, Toshima S, Kashiki Y, Yoshimi N, et al. ACE inhibitors and reduction of the risk of pneumonia in elderly people. Am J Hypertens 2000;13:1050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arai T, Yasuda Y, Toshima S, Yoshimi N, Kashiki Y. ACE inhibitors and pneumonia in elderly people. Lancet 1998;352:1937-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arai T, Yasuda Y, Takaya T, Toshima S, Kashiki Y, Shibayama M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor antagonists, and pneumonia in elderly hypertensive patients with stroke. Chest 2001;119:660-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arai T, Sekizawa K, Ohrui T, Fujiwara H, Yoshimi N, Matsuoka H, et al. ACE inhibitors and protection against pneumonia in elderly patients with stroke. Neurology 2005;64:573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mortensen EM, Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Pugh J. The impact of prior outpatient ACE inhibitor use on 30-day mortality for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Pulm Med 2005;5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harada J, Sekizawa K. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and pneumonia in elderly patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mortensen EM, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA, Restrepo MI, Cornell JE, Anzueto A, et al. Impact of statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality of subjects hospitalised with pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2008;31:611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP, Hill AT. Prior statin use is associated with improved outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2008;121:1002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Myles PR, Hubbard RB, Gibson JE, Pogson Z, Smith CJ, McKeever TM. The impact of statins, ACE inhibitors and gastric acid suppressants on pneumonia mortality in a UK general practice population cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:697-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Poster presentations from the World Congress of Cardiology Scientific Sessions 2010. Circulation 2010;xx:e348.

- 74.Mukamal KJ, Ghimire S, Pandey R, O’Meara ES, Gautam S. Antihypertensive medications and risk of community-acquired pneumonia. J Hypertens 2010;28:401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okaishi K, Morimoto S, Fukuo K, Niinobu T, Hata S, Onishi T, et al. Reduction of risk of pneumonia associated with use of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitors in elderly inpatients. Am J Hypertens 1999;12:778-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.El Solh AA, Brewer T, Okada M, Bashir O, Gough M. Indicators of recurrent hospitalization for pneumonia in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:2010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takahashi T, Morimoto S, Okaishi K, Kanda T, Nakahashi T, Okuro M, et al. Reduction of pneumonia risk by an angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor in elderly Japanese inpatients according to insertion/deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene. Am J Hypertens 2005;18:1353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van de Garde EM, Souverein PC, Hak E, Deneer VH, van den Bosch JM, Leufkens HG. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use and protection against pneumonia in patients with diabetes. J Hypertens 2007;25:235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marciniak C, Korutz AW, Lin E, Roth E, Welty L, Lovell L. Examination of selected clinical factors and medication use as risk factors for pneumonia during stroke rehabilitation: a case-control study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009;88:30-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:169-73S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walter U, Knoblich R, Steinhagen V, Donat M, Benecke R, Kloth A. Predictors of pneumonia in acute stroke patients admitted to a neurological intensive care unit. J Neurol 2007;254:1323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roth EJ, Lovell L, Harvey RL, Heinemann AW, Semik P, Diaz S. Incidence of and risk factors for medical complications during stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2001;32:523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vermeij FH, Scholte op Reimer WJ, de Man P, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Franke CL, de Jong G, et al. Stroke-associated infection is an independent risk factor for poor outcome after acute ischemic stroke: data from the Netherlands Stroke Survey. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;27:465-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hilker R, Poetter C, Findeisen N, Sobesky J, Jacobs A, Neveling M, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia after acute stroke: implications for neurological intensive care medicine. Stroke 2003;34:975-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Katzan IL, Cebul RD, Husak SH, Dawson NV, Baker DW. The effect of pneumonia on mortality among patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Neurology 2003;60:620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arai T, Yasuda Y, Takaya T, Toshima S, Kashiki Y, Yoshimii N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and symptomless dysphagia. Chest 2000;117:1819-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sagnella GA, Rothwell MJ, Onipinla AK, Wicks PD, Cook DG, Cappuccio FP. A population study of ethnic variations in the angiotensin-converting enzyme I/D polymorphism: relationships with gender, hypertension and impaired glucose metabolism. J Hypertens 1999;17:657-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hu Z, Jin X, Kang Y, Liu C, Zhou Y, Wu X, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome among caucasians. J Int Med Res 2010;38:415-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brown NJ, Blais C Jr, Gandhi SK, Adam A. ACE insertion/deletion genotype affects bradykinin metabolism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1998;32:373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van de Garde EM, Endeman H, Deneer VH, Biesma DH, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Ruven HJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and risk and outcome of pneumonia. Chest 2008;133:220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ramirez J, Aliberti S, Mirsaeidi M, Peyrani P, Filardo G, Amir A, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kranzhöfer R, Schmidt J, Pfeiffer CA, Hagl S, Libby P, Kübler W. Angiotensin induces inflammatory activation of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:1623-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wösten-van Asperen RM, Lutter R, Haitsma JJ, Merkus MP, van Woensel JB, van der Loos CM, et al. ACE mediates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats via angiotensin II but not bradykinin. Eur Respir J 2008;31:363-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Antunes G, Evans SA, Lordan JL, Frew AJ. Systemic cytokine levels in community-acquired pneumonia and their association with disease severity. Eur Respir J 2002;20:990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gullestad L, Aukrust P, Ueland T, Espevik T, Yee G, Vagelos R, et al. Effect of high- versus low-dose angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on cytokine levels in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:2061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Eurich DT, Padwal RS, Marrie TJ. Statins and outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia: population based prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006;333:999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Corrales-Medina VF, Suh KN, Rose G, Chirinos JA, Doucette S, Cameron DW, et al. Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy

Supplementary figures 1-13