Abstract

Background

A major barrier to youth recovery is finding suitable sobriety-supportive social contexts. National studies reveal most adolescent addiction treatment programs link youths to community 12-step fellowships to help meet this challenge, but little is known empirically regarding the extent to which adolescents attend and benefit from 12-step meetings or whether they derive additional gains from active involvement in prescribed 12-step activities (e.g., contact with a sponsor and other fellowship members). Greater knowledge in this area would enhance the efficiency of clinical continuing care recommendations.

Methods

Adolescent outpatients (N=127; M age 16.7; 75% male; 87% White) enrolled in a naturalistic study of treatment effectiveness were assessed at intake and 3, 6, and 12 months later using standardized assessments. Mixed-effects models, controlling for static and time-varying confounds, examined the concurrent and lagged effects of 12-step attendance and active involvement on abstinence over time.

Results

The proportion attending 12-step meetings was relatively low across follow-up (24–29%), but more frequent attendance was independently associated with greater abstinence in concurrent and, to a lesser extent, lagged models. An 8-item composite measure of 12-step involvement did not enhance outcomes over and above attendance, but separate components did; specifically, greater contact with a 12-step sponsor outside of meetings and more verbal participation during meetings.

Conclusions

The benefits of 12-step participation observed among adult samples extend to adolescent outpatients. Community 12-step fellowships appear to provide a useful sobriety-supportive social context for youth seeking recovery, but evidence-based youth-specific 12-step facilitation strategies are needed to enhance outpatient attendance rates.

Keywords: recovery, adolescents, alcoholics anonymous, narcotics anonymous, groups, self-help, mutual help, treatment, substance use disorder

1. Introduction

The misuse of alcohol and other drugs confers a prodigious burden of disease and a pervasive negative social and economic impact (Babor et al., 2010; Harwood, 2000; World Health Organization, 2011). Experimentation with these substances typically begins during adolescence and, for a significant minority of youth, escalates into severe problems that can have immediate and long-term consequences (Aarons et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2011; Fombonne, 1998; Fowler et al., 1986; Hser and Anglin, 2011; McLellan et al., 2000; Tapert and Brown, 2000). As with many disorders, however, the sooner treatment is begun the shorter its duration and impact (Dennis et al., 2005). Consequently, providing effective adolescent intervention has become a public health priority (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2011). Increased attention on developing, testing, and implementing effective interventions for adolescents with SUD has increased in the past 10 years (Dennis et al., 2004), but relapse rates following treatment remain high and the cost and limited youth-specific care availability in most communities make ongoing professionally-delivered continuing care challenging (Godley et al., 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

1.1. Mutual-help organizations and continuing care

Mutual-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) are an important component of the overall societal response to ameliorating the negative impact of SUD (Humphreys et al., 2004; Kelly and Yeterian, 2008; Kelly and Yeterian, in press). Strengths of these recovery resources are their ubiquity and local accessibility, minimizing transportation cost and travel time, as well as their flexible availability at times of high relapse risk, such as evenings, weekends, and holidays, when professional care is often not available. For youth seeking recovery from SUD they can provide access to a recovery supportive social network that can facilitate engagement in alternative sober activities outside of formal meetings (Kelly et al., 2008). Notably, they are provided free of charge apart from voluntary contributions, obviating financial access barriers. In contrast, these organizations are peer-led, anonymous, and possess a decentralized authority structure characterized by individual group autonomy (Alcoholics Anonymous, 1953). Consequently, there is no professional accountability, clinical oversight, or “quality control”, potentially increasing variability in any derived therapeutic benefit (Kelly et al., 2011).

1.2. Evidence regarding the role of 12-step mutual-help groups in youth recovery

Nationally representative studies of adolescent SUD treatment programs reveal nearly half (47%) require participation in 12-step mutual help groups during treatment and 85% link adolescents with AA or NA groups as a continuing care resource at discharge (Kelly and Yeterian, 2008; Knudsen et al., 2008). Relative to the high degree of clinical confidence in the utility of these recovery resources for young people, there has been a dearth of research and empirical support for youth involvement in these groups. The limited extant work published in this area does suggest groups such as AA and NA can help adolescents maintain recovery over the short and long-term up to 8 years following treatment (Alford et al., 1991; Chi et al., 2009; Hsieh et al., 1998; Kelly et al., 2008; Kelly and Myers, 2007; Kelly et al, 2010; Kelly et al., 2000; Kelly et al., 2002; Kennedy and Minami, 1993). However, much of this research has been limited in scientific rigor, scope, and clinical setting. Specifically, several studies have been cross-sectional, many have not controlled for potential confounders, and most have been conducted with inpatient samples (Kelly and Myers, 2007). This is problematic since the majority of SUD adolescent treatment services are now delivered in outpatient settings (Knudsen et al., 2008), and the generalizability of research findings from more intensive inpatient to less intensive outpatient samples is unknown. Furthermore, nearly all prior studies have examined AA/NA meeting attendance without describing or investigating the impact of other indices of more active 12-step involvement (e.g., getting and using a sponsor, active participation during 12-step meetings, social engagement with members outside of meetings).

Indices of involvement such as these are important to 12-step theory as they are deemed vital in expediting social engagement in the 12-step fellowship and in facilitating successful completion of AA/NA’s 12-steps (e.g., AA, 1953, pg 61). They represent key 12-step activities that feature prominently within the AA and NA literatures (e.g., AA, 1983; NA, 2004; AA, 2001) and that are prescribed by addiction therapists within treatment programs (Kaskutas et al, 2009). These factors may be particularly important to examine among youth samples, since the social aspects of involvement may facilitate the development of relatively rare recovery-supportive social contexts found important to facilitating long-term recovery (Kelly et al, 2010; Litt et al, 2009; Stout et al, in press). Despite this, there is only limited empirical information on the utility of these commonly prescribed activities among adults (Majer et al., 2011; Montgomery et al., 1995; Weiss et al., 2005) and even less evidence is available for adolescents. Two youth studies reported indices of involvement over and above attendance: one with inpatient youth did not find that active 12-step involvement predicted outcomes over and above attendance (Kelly et al, 2002). However, a recent study of outpatient youth did find beneficial associations between AA/NA attendance, a multi-item measure of 12-step affiliation, and outcomes up to three years following the index treatment episode (Chi et al., 2009). In summary, generally very little is known about 12-step involvement beyond simple attendance, especially among adolescents, including, in particular, the effects that it may have over and above attendance on adolescent treatment outcomes. Greater knowledge in this area would enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of clinical continuing care recommendations.

1.3. Study aims

In a prior analysis of the current sample, we examined multi-level predictors of 12 step attendance during outpatient SUD treatment and examined whether attending 12-step meetings was independently associated with better outcomes during, and in the 3 months following, outpatient treatment (Kelly et al, 2010). In the prior analysis, greater substance involvement and a more severe clinical profile predicted more AA/NA attendance and greater AA/NA attendance during outpatient treatment was associated independently with significantly better substance use outcome concurrently and in the ensuing three months. Here we extend the analysis across the entire follow-up year with specific focus on testing the incremental effects of active indices of 12-step involvement. Our aims were three-fold. First, we sought to describe the degree of adolescent attendance and active involvement in prescribed 12-step activities in AA/NA and other mutual-help groups during the year following admission to outpatient treatment. Second, we tested the effects of concurrent and delayed influences of 12-step attendance and active involvement on substance use outcome over 1 year following outpatient treatment entry. We hypothesized that both meeting attendance and active involvement would predict better outcomes, and that active involvement would produce an incremental benefit over and above attendance. Third, given the importance of specific elements of 12-step involvement (e.g., having an AA/NA sponsor), we explored the incremental effects of individual involvement indices over and above attendance.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 127 adolescents who presented for care at an outpatient SUD treatment in the Northeastern U.S. between August, 2006 and May, 2009. Individuals were eligible if they (a) were within their first month of treatment, (b) were aged 14–19 at the time of study entry, (c) had a parent/guardian consent to participation (if under 18), and (d) were English-speaking. Exclusion criteria were (a) active psychosis or (b) organic brain/cognitive disorder affecting comprehension of the study and its risks and benefits. Of the 178 adolescents who presented for treatment during the enrollment period, 160 (90%) were eligible to participate. Of these, 95% (n = 152) agreed to be contacted by study staff and 127 (79.4%) enrolled. Reasons for non-participation (n = 25) included (a) study staff unable to contact patient within their first month of treatment (24%), (b) patient unable/unwilling to schedule an appointment within the first month of treatment (24%), (c) patient did not attend treatment and chose not to participate in the study as a result (24%), (d) parent declined to give consent for their minor child (20%), (e) patient directly declined participation (4%), and (f) transportation difficulties (4%). Females were disproportionately less likely to enroll in the study than males; 40% of those who declined participation were female, but females comprised only one-quarter of eligible patients.

Of the 127 adolescents enrolled in the study, 95% (n=120) completed the 3-month follow-up, 91% (n=116) completed the 6-month follow-up, and 87% (n=111) completed the 12-month follow-up. There were no significant differences between those who did and did not complete a 3-month assessment on baseline demographic and clinical variables (ps > .07). However, those not completing the 6-month assessment were younger (M = 16.0, SD = 1.4) than completers (M = 16.7, SD = 1.2, p = .04), and non-Whites were less likely to complete than Whites (χ2 = 7.85, p = .005).

The final sample was 75.6% male, 86.6% White, and 16.7 years old (SD = 1.2) at the time of study entry. At baseline, most participants were living at home with at least one parent (93.7%) and were enrolled in school (75.6%); about half were unemployed (56.8%) and justice system involved (50.4%). Marijuana was the most commonly reported drug of choice (70.9%), followed by alcohol (11.8%), heroin/narcotics (11.1%) and cocaine/amphetamines (3.2%). The vast majority (93.7%) met lifetime DSM-IV criteria for an SUD; 26.8% met criteria for marijuana abuse (without dependence), 57.5% for marijuana dependence, 27.6% for alcohol abuse (without dependence), 31.5% for alcohol dependence, 2.4% for opiate abuse (without dependence), and 11.0% for opiate dependence. Approximately 61% met DSM-IV criteria for at least one past-year Axis I condition other than SUD.

2.2. Treatment Site

Participants were recruited from a private, for-profit SUD treatment facility that offers adolescent group, individual, and family treatment; medication (including a buprenorphine/naloxone program); and parent group and individual treatment. They were asked to participate in a study of adolescent treatment effectiveness. Treatment is abstinence-focused and based on a combination of CBT, MET, and 12-step models. The facility offers an aftercare program, and reported referral and linkage to community-based 12-step meetings. The typical course of treatment for adolescent patients at this facility includes an intake assessment, attendance at 12 weekly or biweekly 60-minute group treatment sessions, and a formal reassessment following the initial 12-week phase of treatment. In the current sample, the mean number of sessions attended during the first three months was 11.5 (SD = 6.2; Median = 11; range 0–44). One patient attended no sessions and three patients attended more than 26 sessions. Treatment is abstinence focused, and based on an eclectic model that combines CBT, MET, and 12-Step. While patients are not formally “discharged” from the program, clinical directors reported that the facility offers an aftercare program, referral and linkage of clients to community-based 12-step meetings, and referral of clients to other community-based resources following treatment. One clinical director also completed the Drug and Alcohol Program Treatment Inventory (DAPTI; (Swindle et al., 1995), an 80-item survey designed to assess the goals and activities of SUD programs across eight theoretical orientations. The program scored the highest on Cognitive-Behavioral (17/24), and the lowest on 12-Step (1/24). However, staff reported high rates of referral to 12-step meetings (88% of patients). Compared to a nationally representative survey of 154 adolescent substance use disorder treatment programs (Knudsen et al., 2008), the study facility is similar to the majority in terms of the level of care (standard outpatient; 69.1% of programs surveyed), type of treatment offered (group therapy M = 1.39x/week), theoretical treatment model (mixed/eclectic, 42.4%; use of elements of CBT, 96.0%), and continuing care approaches (linking clients to community-based 12-step programs and other programs, 84.7% and 80.5%, respectively; offering an aftercare program, 50.7%). Like the majority of programs surveyed (71.3%), the current facility does not offer a smoking cessation program. However, it does offer psychiatric medications for co-occurring disorders (42.7% of programs surveyed). Overall, these comparisons suggest that the study facility is representative of available adolescent treatment in the U.S.

2.3. Procedure

Eligible patients and their parents (when appropriate) were informed about the study by clinical staff during the intake assessment. Participants completed the baseline assessment as close as possible to their treatment start date (M days = 10.6, SD = 12.4), followed by 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up assessments. The baseline assessment was completed in 2–3 hours, and the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups took 1–2 hours. Participants were paid by check at the end of each assessment: $50 at baseline and 12-month follow up, and $40 at both 3- and 6-months. Assessments took place at the outpatient treatment facility (91%), over the phone (6%) or in-person at the office of the study staff (3%). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board and a federal Certificate of Confidentiality was also obtained through the study’s funder, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

2.4. Measures

Twelve-Step Attendance and Active Involvement

Attendance at 12-step mutual-help organizations was assessed using the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) at each time point. The baseline, 3-month and 6-month follow-up assessments covered meetings attended in the past 90 days, while the 12-month follow-up covered the past 180 days. These data were used to construct indicators of any attendance, weekly attendance, and percent days of attendance for each follow-up period. Active 12-step involvement at each time point was measured using the Multidimensional Mutual-Help Activity Interview (MMHAI) (Kelly et al., 2011). This short structured interview provides in-depth information on mutual-help group participation across several dimensions and types of fellowships (i.e., AA, NA, CA, as well as “other” and non 12-step groups). Three dimensions of involvement were included in the present study: 1. meeting participation (e.g., active engagement in meetings, such as verbal participation during meetings or helping to set up/run meetings); 2. fellowship involvement (i.e., considering self a fellowship member, active engagement in fellowship and activities, such as obtaining a sponsor, having contacts with members outside of meetings); 3. step work (i.e., progress in working through the 12-step program of action). These data were used to derive a summary index of active involvement based on the sum of 8 dichotomous indicators: consider yourself a member, have a sponsor, contacted your sponsor outside of meetings, contacted other members outside of meetings, read 12-step literature outside of meetings, talked or shared during meetings, helped to set up or run meetings, and completed any steps. Internal consistency of the composite measure was high (Kuder-Richardson Formula 20: 0m=.87, 3m=.88, 6m=.88, 12m=.95). Although assessed separately for different types of fellowships, data were collapsed across fellowships due to low rates of participation in fellowships other than AA.

Recent Substance Use and Prior Treatment

At all timepoints, the TLFB (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) and Form-90 (Miller and Del Boca, 1994) were used in conjunction to examine recent substance use and treatment experiences. Participants used a calendar to record their inpatient and outpatient treatment experiences and to estimate the frequency and timing of substance use. As with 12-step meeting attendance, baseline, 3- and 6-month assessments covered the past 90 days, while the 12-month follow-up covered the past 180 days. From these measures, percent days abstinent (PDA) was calculated by dividing the number of days of no alcohol/drug use (excluding nicotine) by the total number of days in the time period and multiplying by 100. A dichotomous indicator was created flagging any receipt of inpatient SUD treatment for each follow-up period. Outpatient SUD treatment was measured as the total number of weeks of care received during each follow-up. The Form-90 has shown good test-retest reliability and construct validity in adult and adolescent samples (Slesnick and Tonigan, 2004; Tonigan et al., 1997).

Abstinence Goal

At baseline, participants were asked by research staff to verbally state their goals separately for future alcohol use and future drug use with an item from the Customary Drinking and Drug use Record (CDDR; Brown, Myers, Lippke, Tapert, Stewart, Vik, 1998). Responses were recorded verbatim and categorized as continued use (0) or complete abstinence from all substances (i.e., alcohol and other drugs) (1).

Abstinence Self-Efficacy

At baseline, participants rated the likelihood that they would stop drinking alcohol or stop using drugs in the next 90 days on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely won’t stop) to 10 (will stop for sure), separately for alcohol and other drugs. While a coefficient alpha cannot be calculated, single-item measures have the psychometric advantages of greater face validity, easier adaption to new populations, and reduced chance of common method variance (Gardner et al., 1998; Nagy, 2002).

Biological Verification of Self-Report

At follow-ups, if youth reported abstinence from substances (excluding alcohol and nicotine) in the past three months, they were asked to provide a saliva sample. Biological verification of self-reported abstinence was conducted using Intercept Oral Fluid Drug Test kits, which test saliva for the presence of seven substances (amphetamines, methamphetamines/MDMA, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine) using an Oral 7 Panel screen. Saliva samples were analyzed independently at Kroll Laboratory Specialists, Inc. Only 0.9% (one instance) had a positive result inconsistent with a self-report of abstinence.

2.5. Analysis

We first computed descriptive statistics documenting 12-step attendance and active involvement at intake and over the following year. Levels of attendance (weekly or more and percent days) are reported both for the full sample, and in the subsample who reported any attendance. Percentages and levels of active involvement (meeting participation, fellowship involvement, and step work) are reported for those who attended meetings during each assessment period.

To test the concurrent and lagged influences of percent days of 12-step attendance and the 8-item composite measure of active involvement on PDA, we first computed Spearman correlations. We then fitted mixed-effects models with the repeated measures of PDA as the dependent variable, and time-varying measures of 12-step meeting attendance and involvement as predictors. We used this exact same approach to explore the effects from individual aspects of 12-step involvement (e.g., contact with 12-step sponsor, contact with other 12-step members outside of meetings). All models used maximum likelihood estimation, including random intercepts and slopes for time and specifying an unstructured covariance matrix. Time was modeled as a categorical variable using effect coding (reference category = baseline), due to the non-linear (inverted U-shaped) association with PDA. Models controlled for PDA, alcohol and drug abstinence self-efficacy, and abstinent treatment goal at baseline, and time-varying indicators of any ongoing professional outpatient and inpatient SUD treatment. These variables were found in a previous analysis to predict substance-related outcomes in this sample (Kelly et al., 2010). All models adjusted also for predictors of attrition (i.e., age and ethnicity), as recommended (Singer and Willett, 2003).

Models estimated first the main effect of meeting attendance, followed by the incremental value of active involvement in predicting PDA. In the concurrent models, the 12-step measures and time-varying covariates were assessed concurrently with PDA. In the lagged models, the 12-step measures and time-varying covariates were lagged one time period behind PDA. The latter models were run to establish temporal precedence and enhance causal attributions for the influences of 12-step attendance and involvement on PDA. Model pseudo-R2 statistics were calculated as outlined by Singer and Willet (2003). Analyses were conducted in Stata 11.1 and used an alpha of .05.

3. Results

3.1.12-step attendance and active involvement over time

3.1.1. Meeting attendance

At baseline, 42.5% (n=54) reported ever having attended a 12-step meeting in their lives. This percentage increased to 52.5% (n=63) at 3 months, 56.9% (n=66) at 6 months, and 62.2% (n=69) at 12 months, signifying new initiates to 12-step fellowships during the follow-up period. Rates of recent 12-step meeting attendance during each assessment period (90 or 180 days) remained fairly stable over time, ranging from 24–29% (Table 1). Only a minority (11–16%) attended meetings on a weekly basis or more often during the study period. In the subsample of those who did attend meetings, however, the percentage who attended weekly or more often increased from 38% at baseline to 64% and 58% at 6 and 12 months, respectively.

Table 1.

Rates of recent 12-step meeting attendance among adolescents over time1

| Meeting attendance | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Any attendance | 29.1 (37) | 28.3 (34) | 24.1 (28) | 27.9 (31) |

| Weekly attendance or more (full sample) | 11.0 (14) | 11.7 (14) | 15.5 (18) | 16.2 (18) |

| Weekly attendance or more (among attendees) | 37.8 (14) | 41.2 (14) | 64.3 (18) | 58.1 (18) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

|

| ||||

| % days attended (full sample) | 6.2 (17.4) | 5.4 (15.4) | 5.9 (15.5) | 9.0 (21.8) |

| % days attended (among attendees) | 21.4 (26.9) | 19.2 (24.3) | 24.7 (23.4) | 32.2 (31.1) |

N: 127 at baseline, 120 at 3 months, 116 at 6 months, and 111 at 12 months. Baseline, 3-month and 6-month assessments cover a 90-day (13-week) period; 12-month assessment covers a 180-day (26-week) period.

In the full sample, meeting attendance occurred on about 6% of days at intake and in the first 6 months following admission to outpatient treatment, rising to about 9% of days during the second 6 months after admission (i.e., prior to the 12-month follow-up). Among youth who attended at least one meeting during the follow-up periods, meeting attendance increased, occurring on about one in five days prior to baseline and rising to about one in three days prior to the 12-month follow-up.

3.1.2. Active 12-step involvement

Meeting participation, as indexed by the percentage of youth who verbally participated during meetings or who helped to set up or run meetings, was highest in the 6 months prior to the 12-month follow-up, reported by 68% and 39% of adolescent attendees, respectively (Table 2). Both the percentage who considered themselves to be a member of their fellowship and the percentage with a sponsor increased considerably over the study period. Among attendees, the average number of contacts with a sponsor outside of meetings declined from 25 prior to intake, to 6 prior to the 6-month assessment. At each time point, almost all of those who reported a sponsor had at least one contact with them during the assessment period. Contacts with other fellowship members outside of meetings increased over the course of the study period, exceeding half of attendees during the latter two assessment periods. Unlike contacts with sponsors, the average number of contacts among attendees showed a steady increase from intake to 12 months. The percentage of attendees who reported reading 12-step literature outside of meetings increased from 19% at 3 months to 44–45% at the 6- and 12-month assessments. The average number of times that respondents read literature during the assessment periods remained fairly low over time, ranging from 1.4–3.5 times. In the 90 days prior to the baseline, 3-month and 6-month assessments, approximately one-third of attendees reported completing at least one of the 12 steps, with the average number of steps completed per attendee falling below 1. In contrast, 60% of attendees reported completing at least one step in the 180 days prior to the 12-month assessment, and the average number completed was approximately 2 during this time.

Table 2.

Rates of active 12-step involvement among adolescents who attended meetings within each assessment period1

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | M (SD) | % (n) | M (SD) | % (n) | M (SD) | % (n) | M (SD) | |

| Talked or shared in meetings | 40.5 (15) | 18.1 (31.6) | 31.2 (10) | 12.2 (22.6) | 40.0 (10) | 11.4 (23.5) | 67.7 (21) | 30.5 (38) |

| Helped set up or run meetings | 16.2 (6) | 5.1 (15.9) | 15.6 (5) | 3.6 (10.6) | 28.0 (7) | 13.8 (30.2) | 38.7 (12) | 9.8 (21.2) |

| Consider yourself a member | 18.9 (7) | --- | 31.3 (10) | --- | 64.0 (16) | --- | 61.3 (19) | --- |

| Had a sponsor | 13.5 (5) | --- | 18.8 (6) | --- | 40.0 (10) | --- | 45.2 (14) | --- |

| Contact with sponsor outside meetings | 100 (5) | 24.8 (11.6) | 100 (6) | 13.2 (10.0) | 80.0 (8) | 5.7 (8.9) | 100 (14) | 17.7 (17.0) |

| Contact with other members outside of meetings | 32.4 (12) | 3.0 (10.8) | 40.6 (13) | 4.3 (12.5) | 56.0(14) | 5.9 (9.3) | 54.8 (17) | 11.0 (12.4) |

| Read 12-step literature outside of meetings | 29.7 (11) | 3.5 (9.3) | 18.7 (6) | 1.6, (5.3) | 44.0 (11) | 1.4 (2.6) | 45.2 (14) | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Completed steps | 37.8 (14) | 0.81 (1.2) | 37.5 (12) | 0.78 (1.3) | 33.3 (9) | 0.74 (1.3) | 60.0 (18) | 1.8 (2.0) |

N: 37 at baseline, 34 at 3 months, 28 at 6 months, and 31 at 12 months

3.2. Impact of 12-step attendance and involvement on outcome

3.2.1. Bivariate relationships

Overall, mean PDA increased from 45.2% before treatment, to 53.5% at 3-month follow-up, dropping again to 46.4% by the 12-month follow-up (Table 3). PDA levels were correlated over time (r =.26–.67, p’s<.01). Concurrent 12-step attendance and involvement were strongly correlated with each other at each time point (ρ = .79–.90, p’s<.001), with more moderate correlations between subsequent time points (ρ = .39–.63, p’s<.001). At all time points, both 12-step attendance and active involvement showed significant concurrent correlations with PDA (ρ = .21-.43, p’s <.05). Twelve-step attendance showed significant lagged associations with PDA at each follow-up period (ρ = .21–.35, p’s<.05), while active involvement assessed at 3- and 6-months showed significant lagged correlations with PDA at the subsequent 6- and 12-month time points, respectively (ρ = .22–.33, p’s<.05). Baseline PDA also showed significant correlations with subsequent 12-step attendance and involvement at almost all time points (ρ = .19–.27, p’s<.05).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations between PDA, 12-step attendance, and active 12-step involvement over time1

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PDA 0m | 45.2 (34.3) | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. PDA 3m | 53.5 (34.6) | .45*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. PDA 6m | 48.0 (36.7) | .36*** | .67*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. PDA 12m | 46.4 (34.2) | .26** | .41*** | .62*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. 12-step Att 0m | 6.2 (17.4) | .43*** | .21* | .15 | .17 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. 12-step Att 3m | 5.4 (15.4) | .27** | .31*** | .29** | .24* | .44*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. 12-step Att 6m | 6.0 (15.5) | .22* | .17 | .30** | .35*** | .40*** | .56*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. 12-step Att 12m | 9.0 (21.8) | .19* | .11 | .30** | .35*** | .23* | .38*** | .58*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. 12-step Inv 0m | 0.6 (1.5) | .42*** | .14 | .10 | .12 | .83*** | .39*** | .36*** | .29** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. 12-step Inv 3m | 0.6 (1.5) | .27** | .25** | .23* | .24** | .58*** | .83*** | .52*** | .45*** | .56*** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. 12-step Inv 6m | 0.8 (1.7) | .18 | .06 | .21* | .33*** | .33*** | .47*** | .86*** | .63*** | .31** | .49*** | 1.00 | |

| 12. 12-step Inv 12m | 1.2 (2.5) | .22* | .09 | .24* | .34*** | .25** | .37*** | .57*** | .90*** | .31** | .43*** | .65*** | 1.00 |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001; Abbreviations: PDA = percent days abstinent, Att = attendance, Inv = involvement

N: 127 at baseline, 120 at 3 months, 116 at 6 months, and 111 at 12 months

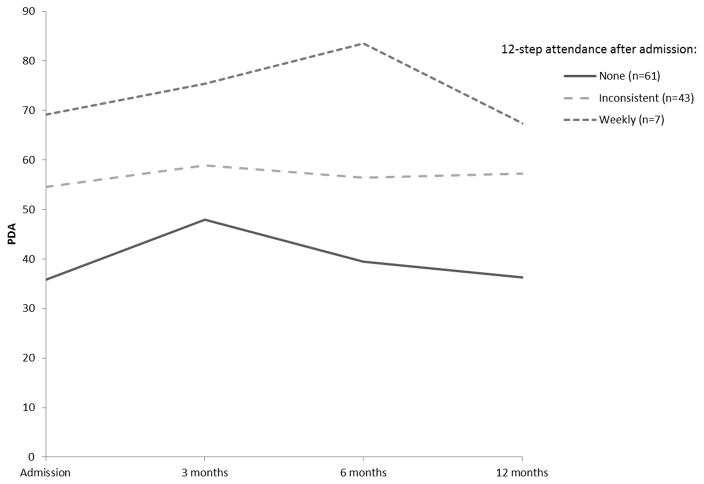

Figure 1 displays trajectories of PDA for three mutually-exclusive groups of 12-step attendees, grouped according to consistent levels of meeting attendance in the 12 months following treatment admission. Those who did not attend any meetings after admission had the lowest levels of abstinence at baseline and over the following year (36–46%). Those who attended sporadically over the entire follow-up year had higher PDA (54–56%), while those who consistently attended weekly or more often exhibited the highest levels of abstinence over time (69–83%).

Figure 1.

Within-person change in PDA for discrete subgroups of 12-step attendees following outpatient SUD treatment (N=111)

3.2.2. Mixed-effects models of the influence of 12-step attendance and involvement over time

There was a significant increase in PDA between baseline and 3-months (Table 4, Concurrent Model). Subsequent levels of PDA dropped off and were not different from baseline. Among the covariates, higher drug abstinence self-efficacy at intake and the receipt of additional inpatient SUD treatment were associated with higher initial and maintained levels of abstinence over the study period. Adjusting for these confounding variables and for predictors of study attrition, concurrent 12-step attendance was a significant independent predictor of abstinence over time. Together, model variables accounted for 21.5% of the overall variance in PDA. The model pseudo-R2 increased by 0.5% (ns) with the addition of concurrent active 12-step involvement to the equation, indicating that involvement did not account for any unique variance in abstinence over and above 12-step meeting attendance. Although attenuated, the impact of 12-step attendance remained significantly associated with PDA in this model. In a reduced model excluding 12-step attendance (not shown), however, active involvement was significantly associated with abstinence (est=4.18, se=0.90, z=4.63, p<.001).

Table 4.

Mixed effects models testing the influence of 12-step meeting attendance and active involvement on PDA over time

| Concurrent Model (N=118) 1 | Attendance | Attendance and Involvement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| est | se | z | est | se | z | |

| Time: | ||||||

| 3m (vs. 0m) | 6.34 | 1.90 | 3.34*** | 6.11 | 1.93 | 3.17*** |

| 6m (vs. 0m) | −1.18 | 1.90 | −0.62 | −0.98 | 1.94 | −0.50 |

| 12m (vs. 0m) | −4.95 | 2.72 | −1.82 | −5.21 | 2.73 | −1.91 |

| Baseline alcohol self-efficacy | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| Baseline drug self-efficacy | 2.43 | 0.65 | 3.75*** | 2.52 | 0.65 | 3.88*** |

| Baseline abstinence goal | 4.37 | 6.08 | 0.72 | 3.94 | 6.09 | 0.65 |

| Outpatient SUD treatment (weeks) | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.91 |

| Inpatient SUD treatment | 10.34 | 4.05 | 2.55* | 9.79 | 4.14 | 2.37* |

| Age | −1.21 | 1.95 | −0.62 | −1.33 | 1.95 | −0.68 |

| White ethnicity | −0.57 | 6.74 | −0.09 | −1.07 | 6.74 | −0.16 |

| 12-step attendance | 0.50 | 0.09 | 5.34*** | 0.38 | 0.13 | 2.85** |

| 12-step involvement | ---- | ---- | ---- | 1.62 | 1.27 | 1.28 |

|

| ||||||

| Lagged Model (N=113)2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Time: | ||||||

| 6m (vs. 3m) | −1.66 | 1.77 | −0.94 | −1.84 | 1.79 | −1.03 |

| 12m (vs. 3m) | −3.69 | 2.61 | −1.41 | −3.75 | 2.66 | −1.41 |

| Baseline alcohol self-efficacy | 0.30 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.84 | 0.36 |

| Baseline drug self-efficacy | 2.73 | 0.74 | 3.67*** | 2.81 | 0.75 | 3.74*** |

| Baseline abstinence goal | 6.77 | 7.03 | 0.96 | 7.39 | 7.13 | 1.04 |

| Outpatient SUD treatment (weeks) | 0.22 | 0.21 | 1.03 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.98 |

| Inpatient SUD treatment | 7.57 | 4.99 | 1.52 | 6.85 | 5.01 | 1.37 |

| Age | −1.85 | 2.25 | −0.82 | −1.77 | 2.28 | −0.78 |

| White ethnicity | −1.96 | 7.80 | −0.25 | −2.28 | 7.87 | −0.29 |

| 12-step attendance | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.83† | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.57 |

| 12-step involvement | ---- | ---- | ---- | 1.24 | 1.58 | 0.78 |

p<.1;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001; Abbreviations: PDA = percent days abstinent

12-step attendance and active involvement, and time-varying covariates (outpatient and inpatient SUD treatment) are concurrent with PDA

12-step attendance and active involvement, and time-varying covariates (outpatient and inpatient SUD treatment) are lagged one time period behind PDA

In lagged models, adjusting for potential confounders and predictors of study attrition, 12-step attendance exhibited a positive lagged effect on abstinence that fell just short of significance (p=.06; Table 4, Lagged Model). That is, meeting attendance in the 90 days prior to the 3-month follow-up showed a trend-level association with greater abstinence in the 90 days prior to 6-month follow-up, and so forth. Together, model variables accounted for 16.9% of the overall variance in PDA. The model pseudo-R2 was unchanged with the addition of lagged 12-step involvement, although the impact of attendance was further attenuated (Table 4). In a reduced lagged model excluding 12-step attendance (not shown), active involvement again was significantly associated with subsequent abstinence (est=2.25, se=1.13, z=2.00, p=.046).

3.2.3 Mixed-model analyses of the increment effects of individual aspects of 12-step involvement on outcome over time

To examine whether important individual elements of 12-step involvement were related to PDA, we ran additional mixed-effects models, with indicators purported to be important to 12-step recovery: contact with sponsor outside of meetings; contact with other members outside of meetings; verbal participation during group meetings; reading 12-step literature outside of meetings; helping setup/run group meetings; and, completion of step work. The analytical method was identical to that used previously, with the exception that individual indices of active involvement were used in place of the summary measure. Results revealed that, over and above the effects of 12-step attendance and the other static and time-varying influences on PDA, more frequent contact with a 12-step sponsor was concurrently associated with higher abstinence (Table 5). More frequent verbal participation during meetings also had an independent positive concurrent influence on outcome, over and above 12-step attendance, that fell just short of significance (p=.07). A significant positive lagged effect also emerged for the frequency of helping to set up or run meetings.

Table 5.

Mixed effects models testing the incremental influence of individual indices of active involvement (over and above 12-step attendance) on PDA over time

| Model | Concurrent (n=118) | Lagged (n=113) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| est | se | t | est | se | t | |

| Contact with sponsor | 0.61 | 0.30 | 2.01* | −0.45 | 0.49 | −0.93 |

| Contact with other members | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 1.58 |

| Read 12-step literature | −0.07 | 0.40 | −0.18 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.07 |

| Talked or shared in meetings | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.93† | −0.12 | 0.09 | −1.41 |

| Helped set up or run meetings | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 2.38* |

| Steps completed | −2.75 | 1.74 | −1.58 | −2.20 | 2.35 | −0.93 |

p<.1;

p<.05; Abbreviations: PDA = percent days abstinent

Models were run separately for each index of 12-step involvement. Estimates adjusted for age, race, baseline self-efficacy and abstinence goal, and time-varying inpatient/outpatient SUD treatment and 12-step meeting attendance (coefficients not shown due to space). In the concurrent models, 12-step attendance and involvement indices, and time-varying covariates are concurrent with PDA. In the lagged models, 12-step attendance and involvement indices, and time-varying covariates are lagged one time period behind PDA. 12-step meeting attendance was significantly associated with PDA in all concurrent models (ps<.001), but not in the lagged models.

4. Discussion

This study extends the prior findings on this sample regarding short term substance use outcomes in relation to 12-step mutual-help attendance to one year, and adds to our understanding of the potential incremental benefit that may be derived from select aspects of 12-step involvement among adolescent outpatients. Findings indicate that between one quarter and one third of the sample attended 12-step meetings during the course of the year-long follow-up. Controlling for a variety of baseline and time-varying confounders and variables related to sample attrition, prospective mixed-effects models revealed that greater adolescent 12-step attendance was related to better treatment outcomes both concurrently and, to a lesser extent, in subsequent time periods. A multi-item composite measure assessing 12-step involvement also positively predicted outcome, but had no incremental influence over and above 12-step meeting attendance. Conversely, exploratory analyses examining theoretically important individual components of the composite measure revealed that more frequent contact with a 12-step sponsor outside of meetings and, to a lesser extent, active verbal participation during 12-step meetings was associated with an incremental benefit on PDA over and above meeting attendance. Results support the utility of community 12-step mutual-help participation as a continuing care resource for outpatient youth and suggest additional benefit may be derived from select aspects of active 12-step involvement.

As noted in our prior work with the current sample examining during treatment attendance on substance use outcomes (Kelly et al, 2010), the percentage of adolescents in this outpatient treatment sample attending 12-step meetings during and in the year post-treatment was lower than that observed among adolescents treated in inpatient settings (Alford et al., 1991; Kelly et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2000; Kennedy and Minami, 1993), but was similar to that reported in another study of adolescents in outpatient SUD treatment (Chi et al., 2009). Because the majority of inpatient samples were treated in programs that utilized 12-step philosophy to a much greater extent, it may be that youth in the current, mostly CBT-oriented, treatment sample were less exposed to the 12-step concepts that prepare individuals to become more effectively engaged with 12-step organizations (Kaskutas et al., 2009). Among outpatient providers nationally, most report linking youth to AA and NA post-treatment, but few are based on 12-step philosophy (Knudsen et al, 2008). Strong endorsement by treatment programs of 12-step participation has been found to influence the likelihood that patients will attend AA/NA post-treatment (Humphreys, 2004; Kelly and Moos, 2003; Tonigan et al., 2003). It is unclear, however, whether adolescent programs adapt and utilize strategies, such as Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF), which have been shown to be helpful among adults (Kahler et al., 2006; Kaskutas et al., 2009; Litt et al., 2009; Timko and DeBenedetti, 2007; Timko et al., 2006; Tonigan et al., 2003; Walitzer et al., 2009). This gap should be addressed in future research. Furthermore, although one might reasonably surmise from findings in the current youth and adult TSF science base that youth more exposed to professionally-led 12-step oriented treatment strategies would become more involved in 12-step mutual-help organizations post-treatment (and thus have better outcomes), randomized studies with young people are sorely needed to determine more definitively the degree to which youth may benefit from TSF strategies.

Rigorous mixed-effects analyses, controlling for a variety of static and time-varying confounds, revealed that 12-step attendance was independently associated with better outcome. Given the relatively small sample, it is notable that 12-step attendance still had a significant independent beneficial effect on outcome when examined concurrently, and when predicting subsequent PDA, although the effect was smaller. Importantly, going to AA/NA meetings helped these adolescents achieve sobriety, irrespective of whether their initial goal at treatment entry was to stay completely abstinent or not, the degree of confidence in their ability to achieve abstinence, or whether they received further professional SUD treatment during the follow-up period. This independent salutary effect of 12-step participation was found also in the 3-year adolescent outpatient study by Chi and colleagues (2009).

Youth attending 12-step meetings were also actively pursuing additional prescribed 12-step activities. Consequently, the two constructs of attendance and involvement were highly correlated. Possibly due to this large degree of shared variance, and despite each individually predicting better outcome in multivariable analyses, our measure of involvement did not enhance outcome over and above attendance. Instructive, however, was that important individual elements of commonly prescribed 12-step activities, such as contacting a sponsor outside of meetings and active verbal participation during meetings, was associated with an incremental benefit over and above those derived solely from attending meetings. Unexpectedly, helping set up meetings was related to PDA in lagged, but not concurrent, models. It is somewhat counterintuitive that any of these involvement indices would be associated with PDA in lagged models but not concurrently. Also, other important aspects of involvement such as working the 12-steps, contact with other members outside of meetings, and reading 12-step literature, did not boost outcomes beyond attendance effects. It may have been that these particular aspects were more highly correlated with attendance and consequently could not explain additional unique variance as was the case with the composite measure. However, these exploratory findings highlight the potential importance of examining individual elements of 12-step involvement (Chi et al., 2009). They also provide preliminary support for the notion that among adolescents taking a more active speaking role during meetings and getting and communicating with an AA or NA sponsor between meetings may boost outcomes over and above benefits related to simple attendance.

4.1. Limitations

Generalizations from the current research should be made cautiously in light of certain limitations. Specifically, the sample is from a single, CBT-oriented, outpatient program located in a suburban area in the northeastern United States and consisted of mostly white, male adolescents.. Furthermore, although there was no differential sample attrition during follow-up related to gender, females were less likely to enroll in the study to begin with, and consequently were slightly underrepresented in our sample relative to the total proportion of females entering the clinical facility. Also, the sample size relative to the study goals of detecting potentially small-medium incremental effect sizes, may have resulted in low statistical power and potential type II errors. A further limitation pertains to the relatively long (3-month) time-delay used in our lagged models. This time frame is not ideally suited to assess the likely more proximal effects of AA/NA participation on substance use, for which a daily or weekly temporal resolution may be superior. For example, going to a meeting this evening may enhance the odds of staying sober tonight and tomorrow, and going to 3 meetings this week may enhance the odds of staying sober next week. Future research is needed to investigate such alternative time frames. Finally, the study was correlational by design and thus any causal conclusions regarding the effect of 12-step indices or other variables on outcome should be made in light of these limitations.

In contrast, this study possesses several strengths. It benefits from a representative sample drawn from a highly representative US adolescent outpatient treatment program. Very high follow-up rates were obtained, and self-reports were validated by objective saliva drug tests. In addition, prospective analyses were conducted using well specified models that controlled for theoretically important confounders measured at treatment intake and over time. This analytical approach helps to determine the unique and independent effects attributable to 12-step participation in the absence of randomization and experimental design.

4.2. Conclusions

Substance use typically onsets during adolescence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010) and for a substantial minority escalates into problem use that can have fatal or lifelong repercussions. A major recovery barrier for youth treated for SUD is finding sobriety-supportive contexts. This is because young people are attempting to recover during the life stage when alcohol and other drug use among their peers is higher than at any other time during the human lifespan (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Freely available community mutual-help organizations, such as AA and NA, may provide a relatively rare supportive venue for young people to gain recovery-specific help and enhance the chances of remission and a successful developmental transition into and through emerging adulthood (Kelly et al., 2008). Extending our prior work with this sample, this study is one of the first to demonstrate that these benefits can extend to less severely substance-involved youth treated in CBT-oriented outpatient treatment, and that encouraging youth to attend and actively participate in meetings, and to get and make use of a sponsor, can enhance the benefits of outpatient treatment. Given the relatively low overall rates of 12-step attendance observed in this outpatient sample, however, evidence-based youth-specific TSF strategies are needed to enhance participation.

Acknowledgments

Study was supported by a grant award from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; Kelly, 5R01AA015526-04).

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Coe MT, Myers MG, Garland AF, Ezzet-Lofstram R, Hazen AL, Hough RL. Adolescent alcohol and drug abuse and health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:412–421. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Twelve steps and twelve traditions. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; New York: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Questions and Answers on Sponsorship. Grapevine Inc; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous. The story of how thousands of alcoholics have recovered from alcoholism. 4. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alford GS, Koehler RA, Leonard J. Alcoholics Anonymous-Narcotics Anonymous model inpatient treatment of chemically dependent adolescents: a 2-year outcome study. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52:118–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, et al. Alcohol: No ordinary commodity. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Ramo D, Anderson KG. Long-term trajectories of adolescent recovery. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction Recovery Management. Humana Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chi FW, Kaskutas LA, Sterling S, Campbell CI, Weisner C. Twelve-Step affiliation and 3-year substance use outcomes among adolescents: social support and religious service attendance as potential mediators. Addiction. 2009;104:927–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, Titus JC, Kaminer Y, Webb C, Hamilton N, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Suicidal behaviours in vulnerable adolescents. Time trends and their correlates. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:154–159. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler RC, Rich CL, Young D. San Diego Suicide Study. II. Substance abuse in young cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:962–965. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800100056008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DG, Cummings LL, Dunham RB, Pierce JL. Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1998;58:898–915. [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL. The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102:81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H. Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update methods and data. National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Anglin MD. In: Addiction treatment and recovery careers, in Addiction recovery management: Theory, research and practice. Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Humana Press; New York: 2011. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S, Hoffmann NG, Hollister CD. The relationship between pre-, during-, post-treatment factors, and adolescent substance abuse behaviors. Addict Behav. 1998;23:477–488. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Circles of recovery: Self-help organizations for addictions. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge (UK): 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Wing S, McCarty D, Chappel J, Gallant L, Haberle B, Horvath AT, Kaskutas LA, Kirk T, Kivlahan D, Laudet A, McCrady BS, McLellan AT, Morgenstern J, Townsend M, Weiss R. Self-help organizations for alcohol and drug problems: toward evidence-based practice and policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:151–158. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00212-5. discussion 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Kelly JF, Strong DR, Stuart GL, Brown RA. Development and initial validation of a 12-step participation expectancies questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:538–542. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Subbaraman MS, Witbrodt J, Zemore SE. Effectiveness of Making Alcoholics Anonymous Easier: a group format 12-step facilitation approach. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Brown SA, Abrantes A, Kahler CW, Myers M. Social recovery model: an 8-year investigation of adolescent 12-step group involvement following inpatient treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1468–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Dow SJ, Yeterian JD, Kahler CW. Can 12-step group participation strengthen and extend the benefits of adolescent addiction treatment? A prospective analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Dow SJ, Yeterian JD, Myers M. How safe are adolescents at Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings? A prospective investigation with outpatient youth. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Moos R. Dropout from 12-step self-help groups: prevalence, predictors, and counteracting treatment influences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG. Adolescents’ participation in Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous: review, implications and future directions. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:259–269. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10400612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. A multivariate process model of adolescent 12-step attendance and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. Do adolescents affiliate with 12-step groups? A multivariate process model of effects. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:293–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Urbanoski KA, Hoeppner BB, Slaymaker V. Facilitating comprehensive assessment of 12-step experiences: A multidimensional measure of mutual-help activity. Alcohol Treat Q. 2011;29(3):181–203. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2011.586280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. In: Mutual-help groups, in Evidence-based adjunctive treatments. O’Donohue W, Cunningham JR, editors. Elsevier; New York: 2008. pp. 61–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. Empirical awakening: The new science on mutual-help and implications for cost containment under health care reform. Subst Abus. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.634965. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BP, Minami M. The Beech Hill Hospital/Outward Bound Adolescent Chemical Dependency Treatment Program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10:395–406. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM, Johnson JA. Service delivery and use of evidence-based treatment practices in adolescent substance abuse treatment settings: Project report. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Substance Abuse Policy Research Program (Grant No. 53130) 2008 Retrieved at: http://www.uga.edu/ntcs/reports/Adolescent%20Study%20Summary%20Report.

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Changing network support for drinking: network support project 2-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:229–242. doi: 10.1037/a0015252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer JM, Jason LA, Ferrari JR, Miller SA. 12-Step involvement among a U.S. national sample of Oxford House residents. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery HA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Does Alcoholics Anonymous involvement predict treatment outcome? J Subst Abuse Treat. 1995;12:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy MS. Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2002;75:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Narcotics Anonymous. Sponsorship, revised. Narcotics Anonymous world Services Inc; Van Nuys, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Adolescent substance use: America’s #1 public health problem. National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse; Columbia University; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Tonigan JS. Assessment of Alcohol and Other Drug Use by Runaway Youths: A Test-Retest Study of the Form 90. Alcohol Treat Q. 2004;22:21–34. doi: 10.1300/J020v22n02_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Highlights 2007. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Accessed 14 December 2010]. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) DASIS Series: S-45, DHHS Publication No (SMA) 09-4360 [ http://oas.samhsa.gov/TEDS2k7highlights/toc.cfm] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume 1. Summary of National Findings (NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4856) Office of Applied Statistics; Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swindle RW, Peterson KA, Paradise MJ, Moos RH. Measuring substance abuse program treatment orientations: the Drug and Alcohol Program Treatment Inventory. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:61–78. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Brown SA. Substance dependence, family history of alcohol dependence and neuropsychological functioning in adolescence. Addiction. 2000;95:1043–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95710436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, DeBenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to 12-step self-help groups: one-year outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Debenedetti A, Billow R. Intensive referral to 12-Step self-help groups and 6-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Participation and involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. In: Babor T, DelBoca F, editors. Treatment Matching in Alcoholism. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of Form 90: an instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:358–364. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walitzer KS, Dermen KH, Barrick C. Facilitating involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous during out-patient treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 2009;104:391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop RJ, Najavits LM, Frank A, Crits-Christoph P, Thase ME, Blaine J, Gastfriend DR, Daley D, Luborsky L. The effect of 12-step self-help group attendance and participation on drug use outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]