Abstract

Background:

Little is known about engagement in multiple health behaviours in childhood cancer survivors.

Methods:

Using latent class analysis, we identified health behaviour patterns in 835 adult survivors of childhood cancer (age 20–35 years) and 1670 age- and sex-matched controls from the general population. Behaviour groups were determined from replies to questions on smoking, drinking, cannabis use, sporting activities, diet, sun protection and skin examination.

Results:

The model identified four health behaviour patterns: ‘risk-avoidance’, with a generally healthy behaviour; ‘moderate drinking’, with higher levels of sporting activities, but moderate alcohol-consumption; ‘risk-taking’, engaging in several risk behaviours; and ‘smoking’, smoking but not drinking. Similar proportions of survivors and controls fell into the ‘risk-avoiding’ (42% vs 44%) and the ‘risk-taking’ cluster (14% vs 12%), but more survivors were in the ‘moderate drinking’ (39% vs 28%) and fewer in the ‘smoking’ cluster (5% vs 16%). Determinants of health behaviour clusters were gender, migration background, income and therapy.

Conclusion:

A comparable proportion of childhood cancer survivors as in the general population engage in multiple health-compromising behaviours. Because of increased vulnerability of survivors, multiple risk behaviours should be addressed in targeted health interventions.

Keywords: childhood cancer survivors, health behaviour, cluster analysis, smoking, alcohol consumption

Engagement in health protective behaviour is important for preventing chronic diseases and early mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Khaw et al, 2008) and is of particular importance for childhood cancer survivors (White et al, 2005; Children’s Oncology Group, 2008; Demark-Wahnefried and Jones, 2008; Gritz and Demark-Wahnefried, 2009). Although about 80% are cured from cancer (Horner et al, 2009), survivors are at increased risk for second malignancies and early mortality (Armstrong et al, 2009; Meadows et al, 2009), and two thirds suffer from chronic conditions, such as endocrine disorders, heart problems, neurocognitive impairment and musculoskeletal disorders (von der Weid et al, 1996; Hewitt et al, 2003; Oeffinger et al, 2006).

Only few studies have investigated health behaviours in young adult survivors of childhood cancer (Mulhern et al, 1995; Larcombe et al, 2002; Butterfield et al, 2004; Bauld et al, 2005; Clarke and Eiser, 2007). In general, these studies reported a lower or similar level of engagement in single risk behaviours compared with the general population and controls (Mulhern et al, 1995; Larcombe et al, 2002; Bauld et al, 2005; Clarke and Eiser, 2007). From a public health perspective, it is important to know whether there are groups of individuals who engage in multiple health behaviours simultaneously, and whether such behaviour patterns differ between survivors and controls. Answers to these questions could provide a basis for targeted interventions, using a person-centred approach rather than focusing on single health behaviours. Clustering methods, including latent class analysis (LCA), have been used to identify and characterise health behaviour patterns in various populations (Schneider et al, 2009; Sutfin et al, 2009; Huh et al, 2011). In childhood cancer survivors, LCA has recently been used to classify them according to modifiable cognitive, affective and motivation indicators for future medical follow-up (Cox et al, 2011).

This study aimed to (i) identify and characterise different patterns of health behaviour in a mixed population of childhood cancer survivors and matched controls from the general population using LCA, (ii) assess differences in the prevalence of these behaviour patterns between survivors and controls, and (iii) identify risk factors for health-compromising behaviour patterns in survivors.

Materials and methods

This analysis included 835 adult survivors of childhood cancer from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (SCCSS) and 1670 controls from the Swiss Health Survey (SHS) matched on gender, age, language region and migration background; both surveys were conducted in 2007–2009.

Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

The SCCSS is a nationwide population-based long-term follow-up study of all childhood cancer patients registered in the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (Michel et al, 2007; Kuehni et al, 2011), who were diagnosed with cancer between 1976 and 2003 before age 16 years, and who survived at least 5 years since diagnosis.

Study participants received an extensive questionnaire in German, French or Italian. Non-responders were sent a reminder questionnaire after 2 months and subsequently contacted by phone to encourage them to participate. Ethics approval was provided through the general cancer registry permission of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (The Swiss Federal Commission of Experts for Professional Secrecy in Medical Research) and a statement of no objections was obtained from the ethics committee of the Canton of Bern.

Of 1699 eligible survivors, 1497 could be contacted and 1067 responded (response rate 63% of eligible, 72% of contacted survivors). We included participants aged 20–35 years at the time of survey. Of the 860 eligible respondents, we dropped 10 because of missing values in the question on alcohol consumption—the model required complete data for this variable, because information on frequency of drinking and binge drinking were conditional to a positive reply to this question—and another 15 because of missing information on migration background, which was required for matching controls, leaving 835 survivors for the analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Swiss Health Survey

The SHS is a national representative health survey repeated in 5-year intervals. The 2007 survey included a random sample of 30,179 Swiss households with a telephone landline. A stratified (by region) and stepwise (first selection of households, then of an individual within each household) sampling procedure was applied, with oversampling of households in the French- and Italian-speaking regions of Switzerland. Within each household, one person aged ⩾15 years was randomly chosen for the interview. The response rate was 66% (Bundesamt für Statistik, 2008). For each survivor, two controls from the SHS were matched for gender, age, language, region and migration background, resulting in 1670 controls.

Health behaviours

The SCCSS used a questionnaire similar to that of childhood cancer survivor studies in the US and the UK (Robison et al, 2002; Hawkins et al, 2008). For comparison with the Swiss population, health behaviours were assessed with standardised questions of the SHS. The following health-compromising and protective behaviours were assessed in both populations and included in the LCA to identify health behaviour patterns: smoking, alcohol consumption including binge drinking, cannabis use, skin examination, sun protection, sporting activities and vegetable/fruit consumption (Table 1).

Table 1. Questions used to assess behaviours and prevalence of behaviours among survivors and controls.

|

Survivors (

n

=835)

|

Controls (

n

=1670)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviour | Measurement | Recoded categories | n | % a | n | % a | P -value b |

| Smoking | Do you smoke? If yes, how many cigarettes a day? | None | 634 | 76 | 987 | 65 | <0.001 |

| Up to 9 cigarettes a day | 106 | 13 | 289 | 17 | |||

| 10–19 cigarettes a day | 50 | 6 | 200 | 12 | |||

| One or more packs a day | 40 | 5 | 141 | 8 | |||

| Cannabis use | Have you ever consumed marijuana? | No, never | 469 | 56 | 988 | 59 | 0.309 |

| Previously | 275 | 33 | 512 | 31 | |||

| Currently | 74 | 9 | 167 | 10 | |||

| Drinking | Do you drink alcohol? | No alcohol consumption | 86 | 10 | 177 | 11 | 0.818 |

| Alcohol consumption | 749 | 90 | 1493 | 89 | |||

| How frequently do you usually consume alcoholic drinks (such as wine, beer, schnapps or any other hard liquor)?c | Rarely | 299 | 36 | 517 | 31 | <0.001 | |

| 1–2 times a week | 270 | 33 | 784 | 47 | |||

| >2 times a week | 126 | 15 | 138 | 8 | |||

| 1 or more drinks a day | 51 | 6 | 54 | 3 | |||

| How many times have you drunk more than 8 units (males)/ 6 units (females) at a time in the past year?c | No binge drinking | 273 | 33 | 986 | 59 | <0.001 | |

| Less than once a month | 272 | 33 | 321 | 19 | |||

| Once a month or more | 170 | 20 | 144 | 9 | |||

| Sporting activities | Do you engage in physical exercise or sporting activities? If yes, how intensively do you pursue these activities? | None | 290 | 35 | 556 | 33 | 0.001 |

| Low to moderate intensity | 269 | 32 | 480 | 29 | |||

| Quite intensively | 198 | 24 | 417 | 25 | |||

| Very intensively | 63 | 8 | 217 | 13 | |||

| Diet | How many portionsd of fruit do you eat a day on average? How many portions of vegetables do you eat a day on average? | None (0 to <1 portion a day) | 63 | 8 | 118 | 7 | 0.187 |

| Vegetable or fruit consumption (⩾1 portion a day) | 156 | 19 | 358 | 21 | |||

| Vegetable and fruit consumption (⩾1 portion a day each) | 604 | 72 | 1140 | 68 | |||

| Skin protection | Do you protect yourself from sun exposure? | No | 188 | 23 | 214 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 647 | 78 | 1455 | 87 | |||

| Have you ever had your skin or moles examined by a physician? | No, never | 429 | 51 | 1046 | 63 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, more than 12 months ago | 275 | 33 | 442 | 27 | |||

| Yes, in the last 12 months | 112 | 13 | 127 | 8 | |||

Percentages don’t always add up to 100% due to missing values.

χ2-test.

Asked only to those with alcohol consumption (percentages don’t add up to 100%).

1 portion=size of your fist.

Potential determinants of health-behaviour patterns

In both populations, we examined the following potential determinants of health behaviour: gender, age, marital status, parenthood and socio-economic variables, including income, educational attainment and migration background (one or both parents originating from another country; Table 2). For survivors, we additionally included parents’ education and disease-related information, including age at diagnosis, ICCC-3 code of diagnosis (Steliarova-Foucher et al, 2005), treatment and relapse history. Treatment was categorised into four categories: surgery only, chemotherapy (without radiotherapy, irrespective of surgery), radiotherapy (irrespective of surgery and chemotherapy) and bone marrow transplantation (BMT; irrespective of other therapies).

Table 2. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the two study populations, survivors and controls.

|

Survivors (

n

=835)

|

Controls (

n

=1670)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P -value a | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–25 | 373 | 44.7 | 746 | 44.7 | n.a.b |

| 26–30 | 285 | 34.1 | 570 | 34.1 | |

| 31–35 | 177 | 21.2 | 354 | 21.2 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 441 | 52.8 | 882 | 52.8 | n.a.b |

| Female | 394 | 47.2 | 788 | 47.2 | |

| Language | |||||

| German | 633 | 75.8 | 1266 | 75.8 | n.a.b |

| French/Italian | 202 | 24.2 | 404 | 24.2 | |

| Migration backgroundc | |||||

| No | 648 | 77.6 | 1296 | 77.6 | nab |

| Yes | 187 | 22.4 | 374 | 22.4 | |

| Civil status | |||||

| Single, divorced or widowed | 732 | 88.5 | 1284 | 76.9 | <0.001 |

| Married | 95 | 11.5 | 385 | 23.1 | |

| Education | |||||

| Compulsory schooling | 70 | 8.0 | 69 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Vocational training | 379 | 46.0 | 945 | 56.6 | |

| Higher secondaryd | 304 | 36.4 | 449 | 26.9 | |

| University | 63 | 7.5 | 200 | 12.0 | |

| Income | |||||

| Unemployed | 110 | 13.2 | 43 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| 0–3000 CHF | 239 | 28.6 | 573 | 34.3 | |

| 3001–6000 CHF | 402 | 48.1 | 819 | 49.0 | |

| >6000 CHF | 45 | 5.4 | 235 | 14.1 | |

| Number of children | |||||

| None | 708 | 84.8 | 1325 | 79.3 | <0.001 |

| One | 63 | 7.5 | 169 | 10.1 | |

| Two or more | 41 | 4.9 | 176 | 10.5 | |

| Body mass index (kg m2) | |||||

| <25 | 606 | 72.6 | 1266 | 75.8 | 0.372 |

| ⩾25 | 203 | 24.3 | 388 | 23.2 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||

| ≤ 4 | 228 | 27.3 | |||

| 5–8 | 205 | 24.6 | |||

| 9–12 | 183 | 21.9 | |||

| >12 | 219 | 26.2 | |||

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Leukaemia | 310 | 37.1 | |||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 73 | 8.7 | |||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 83 | 9.9 | |||

| CNS tumours | 101 | 12.1 | |||

| Embryonal tumourse | 127 | 15.2 | |||

| Bone tumours and soft tissue sarcomas | 87 | 10.4 | |||

| Otherf | 54 | 6.5 | |||

| Therapy | |||||

| Surgery only | 81 | 9.7 | |||

| Chemotherapy, but no radiotherapy | 394 | 47.2 | |||

| Any radiotherapy | 257 | 30.8 | |||

| BMT | 95 | 11.4 | |||

| Relapse | |||||

| No | 710 | 85.0 | |||

| Yes | 125 | 15.0 | |||

Abbreviations: CHF=Swiss Francs; CNS=central nervous system; n.a.=not applicable; BMT=bone marrow transplantation.

Numbers do not always sum up to the total because of missing values.

χ2-test.

Population matched for gender, age, language, region and migration background.

Does not have a Swiss passport or has received the Swiss passport after date of birth or parents originate from another country.

Higher secondary education includes high school, teachers training colleges, technical colleges and higher vocational education.

Includes neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, Wilms tumour, liver tumour and germ cell tumour.

Includes epithelial neoplasms, malignant melanomas, unspecified malignant tumours and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Statistical analysis

We first identified different patterns of health behaviour in the combined population of survivors and controls, and subsequently assessed the prevalence and determinants of these behaviours separately in each population. To identify behaviour patterns, we used LCA (Lazarsfeld and Henry, 1968; Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh, 2008), a clustering method that is based on a statistical model and is particularly suited for data collected through questionnaire surveys, because it can appropriately treat categorical data and missing values. Latent class analysis assumes that the population consists of distinct subpopulations (latent classes), which cannot be observed directly, but are inferred from the observed variables. After fitting the model, posterior probabilities of belonging to the identified classes can be computed for each subject (McLachlan and Peel, 2000). We applied LCA to the combined data from survivors and controls (n=2505) on the health behaviours described in Table 1. After fitting the model, subjects were then allocated to the behaviour patterns for which they had the largest membership probability. We refer to the groups thus formed as ‘health-behaviour clusters’. We fitted the models with 1–6 classes and used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to select the final model (McLachlan and Peel, 2000). Selecting the model with lowest BIC optimises model fit while at the same time avoiding over-fitting.

We compared proportions of survivors and controls allocated to the identified health behaviour patterns using χ2-tests. We then assessed associations of potential determinants (demographic, socio-economic and disease related) with health-behaviour patterns using χ2-tests. We subsequently included all variables with significant associations (P<0.05) in the first step in a multinomial logistic regression model with health behaviour clusters as the outcome levels. We investigated whether income and educational attainment (assessed at the time of survey) lie on the causal pathway between potential determinants assessed in childhood (demographic- and disease-related variables, and parents’ education) and health-behaviour patterns by comparing multinomial regression models with and without income and educational attainment.

The Mplus software version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used for LCA and Stata version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for all other analyses.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Mean age was 26.1 years (s.d.=4.1 years; range 20.0–35.0 years) and 53% were male in both study populations (because of matching; Table 2). Fewer survivors were married (12% vs 23%), had children (12% vs 21%), or had a university degree (8% vs 12%). Among survivors, mean age at diagnosis was 7.9 years (s.d.=4.7 years; range 0.0–16.0 years) and mean time since diagnosis was 18.1 years (s.d.=5.8 years; range 5.8–32.5 years); 36% were treated with radiotherapy and 10% had surgery only. A relapse of their primary cancer occurred in 15% of the survivors (Table 2).

Prevalence of health behaviours in survivors and controls

More survivors than controls were non-smokers (76% vs 65% in controls) and had preventive skin examinations by a physician (46% vs 35% Table 1). In contrast, fewer survivors than controls reported protecting themselves from sun exposure (78% vs 87%) and fewer intensively pursued sporting activities (8% vs 13%). More survivors engaged in binge drinking (20% vs 9%).

Identification of health-behaviour clusters

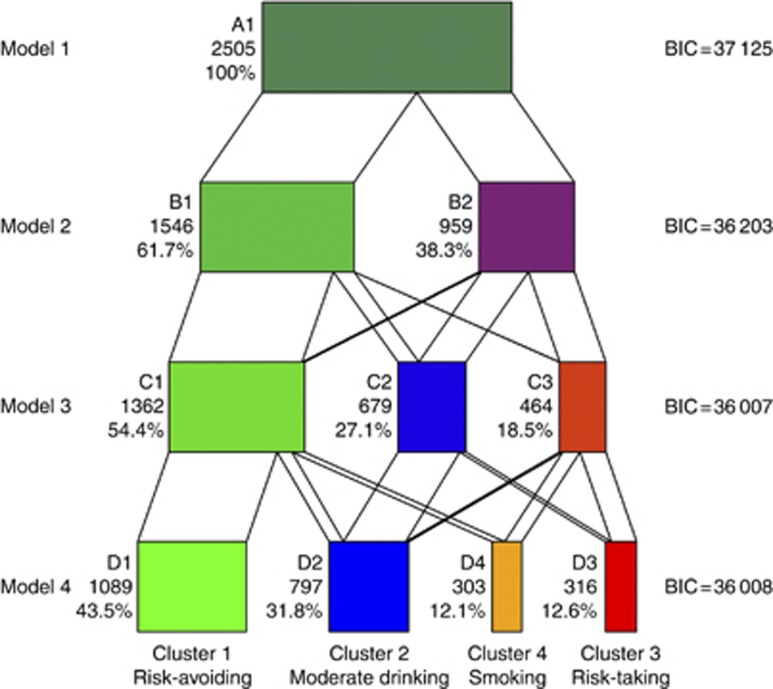

We fitted LCA models with 1–6 classes (Figure 1). The 2-class model distinguished between a ‘low-risk’ group (B1) and a ‘high-risk’ group that engaged in smoking and alcohol use (B2). In the 3-class model, the high-risk group was separated into two new groups, the first characterised by sporting activities and moderate to frequent drinking (C2), and the second by frequent drinking and smoking (C3). In the 4-class model, a new group emerged characterised by frequent smoking, but low alcohol consumption (D4). According to the BIC, the models including 3 and 4 classes were optimal, with BIC values: 36 007 and 36 008 for the 3 and 4, compared with 36 203 and 36 062 for the models with 2 and 5 classes, respectively.

Figure 1.

Illustration of behaviour groups identified by LCA as the number of classes was increased. The boxes in a given layer represent the behaviour groups identified in that model. Numbers of individuals and percentage of sample allocated to the group are reported next to the boxes.

This manuscript reports results for the 4-class model, which highlights differences in behaviour patterns between survivors and controls that are less evident from the 3-class model. Results of the 3-class model are shown in the online supplement (Supplementary Table 1).

Description of health-behaviour clusters

We labelled the four behaviour clusters as: D1 ‘risk-avoiding’ (number of individuals allocated n=1089, 44% of sample), D2 ‘moderate drinking’ (n=797, 32%), D3 ‘risk-taking’ (n=316, 13%) and D4 ‘smoking’ (n=303, 12%).

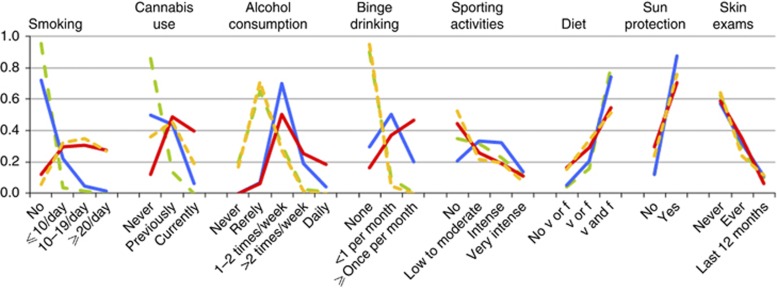

Cluster D1: ‘risk-avoiding’

This cluster includes individuals who did not, or only to a minor extent, engage in risk behaviours, and who reported health-protective behaviours (sporting activities, vegetable and fruit consumption, sun protection and skin examination; Figure 2, green dashed).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of health behaviours within the four health-behaviour patterns identified. The prevalence of the response categories of a given variable are connected with lines to better visualise differences between the behaviour patterns.  , Cluster D1: risk-avaiding;

, Cluster D1: risk-avaiding; , Cluster D2: moderate drinking;

, Cluster D2: moderate drinking; , Cluster D3: risk-taking;

, Cluster D3: risk-taking; , Cluster D4: smoking. Abbreviations: v=vegetables; f=fruits.

, Cluster D4: smoking. Abbreviations: v=vegetables; f=fruits.

Cluster D2: ‘moderate drinking’

This cluster had a similar tendency for health-protective behaviours as the ‘risk-avoiders’, but engaged more frequently in sporting activities and in alcohol consumption, including binge drinking (Figure 2, blue).

Cluster D3: ‘risk-taking’

These individuals tended to engage in all assessed risk behaviours: smoking, marijuana consumption and alcohol use, including binge drinking. In addition, they reported lower engagement in health-protective behaviours compared with the ‘risk-avoiding’ Cluster D1 and ‘moderate-drinking’ Cluster D2 (Figure 2, red).

Cluster D4: ‘smoking’

These individuals had low engagement in health-protective behaviours and were likely to smoke, but not to drink (Figure 2, yellow dashed).

The clusters varied little with respect to sun protection and skin examination (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 2).

Prevalence of health-behaviour clusters in survivors and controls

The prevalence of the four health-behaviour clusters differed between survivors and controls (P-value for χ2-test<0.001). Similar proportions of survivors and controls were allocated to the ‘risk-avoiding’ Cluster D1 (42% of survivors and 44% of controls) and ‘risk-taking’ Cluster D3 (14% of survivors and 12% of controls), a higher proportion of survivors was allocated to the ‘moderate drinking’ Cluster D2 (39% of survivors and 28% of controls) and a smaller proportion to the ‘smoking’ Cluster D4 (5% of survivors and 16% of controls).

The membership probabilities tended to be high for the groups to which subjects were allocated. Mean membership probabilities were 0.89, 0.76, 0.82 and 0.78, for Cluster D1 (‘risk-avoiding’), Cluster D2 (‘moderate drinking’), Cluster D3 (‘risk-taking’) and Cluster D4 (‘smoking’), respectively, and did not differ substantially between survivors and controls.

Socio-demographic characteristics of health-behaviour clusters in survivors and controls

In both populations, gender, education, income and migration background were significantly associated with health-behaviour clusters (Table 3; Supplementary Table S3). Female gender was common in the ‘risk-avoiding’ Cluster D1 (64% of survivors, 62% of controls) and less frequent in the ‘moderate drinking’ Cluster D2 (38% of survivors and 34% of controls) and ‘risk-taking’ Cluster D3 (25% of survivors and 24% of controls). The proportion of individuals with a university degree was highest in the ‘moderate drinking’ Cluster D2 (10% of survivors and 17% of controls). Members of Cluster D2 (‘moderate drinking’) and Cluster D3 (‘risk-taking’) tended to have a higher income than those in other clusters, whereas the percentage of individuals with a migration background was highest in the ‘smoking’ Cluster D4 (45% of survivors and 38% of controls). These associations remained similar in multinomial logistic regression models (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 3. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of health behaviour clusters in survivors and controls.

|

Cluster D1 ‘risk-avoiding’

|

Cluster D2 ‘moderate drinking’

|

Cluster D3 ‘risk-taking’

|

Cluster D4 ‘smoking’

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors ( n =352) | Controls ( n =737) | Survivors ( n =327) | Controls ( n =470) | Survivors ( n =114) | Controls ( n =202) | Survivors ( n =42) | Controls ( n =261) | P-valuea survivors | P-valuea controls | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 20–25 | 46.6 | 40.7 | 41.6 | 44.3 | 49.1 | 53.0 | 40.5 | 50.2 | 0.414 | 0.006 |

| 26–30 | 32.1 | 34.7 | 36.1 | 34.7 | 36.0 | 31.7 | 31.0 | 33.3 | ||

| 31–35 | 21.3 | 24.6 | 22.3 | 21.1 | 14.9 | 15.4 | 28.6 | 16.5 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 36.1 | 38.5 | 62.1 | 66.4 | 74.6 | 75.7 | 61.9 | 51.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female | 63.9 | 61.5 | 37.9 | 33.6 | 25.4 | 24.3 | 38.1 | 49.0 | ||

| Language | ||||||||||

| German | 77.8 | 76.4 | 76.2 | 79.6 | 69.3 | 71.8 | 73.8 | 70.5 | 0.316 | 0.023 |

| French/Italian | 22.2 | 23.6 | 23.9 | 20.4 | 30.7 | 28.2 | 26.2 | 29.5 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single, divorced or widowed | 86.1 | 68.9 | 87.7 | 81.9 | 87.7 | 93.6 | 87.7 | 77.4 | 0.796 | <0.001 |

| Married | 13.1 | 30.9 | 11.4 | 18.1 | 10.5 | 6.4 | 11.9 | 22.6 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory schooling | 11.4 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 16.7 | 8.4 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Vocational training | 44.0 | 55.4 | 45.0 | 50.0 | 47.4 | 60.9 | 54.8 | 68.6 | ||

| Higher secondaryb | 34.4 | 26.5 | 39.8 | 31.9 | 37.7 | 27.2 | 23.8 | 18.8 | ||

| University | 6.5 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 16.6 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 2.4 | 4.2 | ||

| Income | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | 19.9 | 2.3 | 9.2 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 5.0 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| 0–3000 CHF | 33.0 | 36.5 | 23.9 | 31.7 | 27.2 | 33.2 | 33.3 | 33.7 | ||

| 3001–6000 CHF | 40.9 | 46.8 | 54.1 | 47.5 | 51.8 | 55.9 | 52.4 | 52.9 | ||

| >6000 CHF | 2.3 | 14.4 | 8.6 | 18.7 | 7.0 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 8.4 | ||

| Number of children | ||||||||||

| None | 75.0 | 72.7 | 82.6 | 86.0 | 83.3 | 91.1 | 83.3 | 77.0 | 0.265 | <0.001 |

| One | 8.8 | 12.9 | 5.2 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 5.0 | 7.1 | 10.3 | ||

| Two or more | 5.4 | 14.4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 12.6 | ||

| Migration backgroundc | ||||||||||

| No | 75.9 | 79.4 | 81.4 | 82.1 | 80.7 | 81.2 | 54.8 | 61.7 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24.2 | 20.6 | 18.7 | 17.9 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 45.2 | 38.3 | ||

| Body mass index (kgm2) | ||||||||||

| <25 | 72.6 | 74.6 | 77.5 | 77.0 | 69.6 | 77.7 | 85.1 | 75.5 | 0.142 | 0.143 |

| ⩾25 | 27.4 | 24.3 | 22.5 | 22.8 | 30.4 | 19.8 | 14.9 | 23.8 | ||

| Parent's educationd | ||||||||||

| Compulsory schooling | 8.6 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 25.0 | 0.009 | |||||

| Vocational training | 47.3 | 43.3 | 47.8 | 29.2 | ||||||

| Higher secondaryb | 29.1 | 32.5 | 30.4 | 31.3 | ||||||

| University | 9.4 | 12.9 | 13.9 | 4.2 | ||||||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤ 4 | 29.6 | 26.3 | 25.4 | 21.4 | 0.209 | |||||

| 5–8 | 21.9 | 28.1 | 21.9 | 26.2 | ||||||

| 9–12 | 21.3 | 22.3 | 26.3 | 11.9 | ||||||

| >12 | 27.3 | 23.2 | 26.3 | 40.5 | ||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Leukaemia | 33.2 | 40.7 | 40.0 | 35.7 | 0.024 | |||||

| Lymphoma | 17.9 | 17.7 | 24.6 | 16.7 | ||||||

| CNS tumour | 16.8 | 8.3 | 7.0 | 16.7 | ||||||

| Other solid tumoure | 32.1 | 33.3 | 29.0 | 31.0 | ||||||

| Therapy | ||||||||||

| Surgery only | 8.2 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 16.7 | 0.007 | |||||

| Chemotherapy, but no radiotherapy | 42.6 | 51.4 | 57.0 | 26.2 | ||||||

| Any radiotherapy | 36.7 | 26.9 | 22.8 | 33.3 | ||||||

| BMT | 11.9 | 10.7 | 7.9 | 21.4 | ||||||

| Relapse | ||||||||||

| No | 80.1 | 89.3 | 89.5 | 81.0 | 0.003 | |||||

| Yes | 19.9 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 19.1 | ||||||

Abbreviations: CHF=Swiss Francs; CNS=central nervous system; BMT=bone marrow transplantation.

χ2-test for differences in prevalence of characteristics between clusters.

Higher secondary education includes high school, teachers training colleges, technical colleges and higher vocational education.

Does not have a Swiss passport or has received the Swiss passport after date of birth or parents originate from another country.

The highest level of education of either father or mother.

Includes neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, Wilms tumour, liver tumour, germ cell tumour, epithelial neoplasms, malignant melanomas, unspecified malignant tumours and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Data are prevalence in %

Clinical characteristics of health-behaviour clusters in survivors

In survivors, determinants of health-behaviour clusters in adjusted multinomial logistic regression were gender, diagnosis, therapy, relapse, having a migration background and income (Table 4). In females, the odds for having a behaviour pattern other than ‘risk-avoiding’ (Cluster D1) was a third or less of that in males (odds ratio (OR) 0.33 for ‘moderate drinking’ Cluster D2; 0.17 for ‘risk taking’ Cluster D3; 0.33 for ‘smoking’ Cluster D4). Compared with survivors of leukaemia, survivors of a central nervous system tumour were less likely to belong to the ‘moderate drinking’ Cluster D2 (OR 0.38) and ‘risk-taking’ Cluster D3 (0.26). Individuals treated by surgery only were more likely to belong to one of the three risk behaviour clusters D2, D3 and D4 (OR>2) than those treated with chemotherapy, but no radiotherapy, and BMT was associated with the ‘smoking’ Cluster D4 (OR 3.60). Survivors who had a relapse were less likely to belong to a risk cluster (ORs<0.6 for D2, D3 and D4). A migration background was associated with an increased risk for the ‘smoking’ Cluster D4 (OR 2.60).

Table 4. Determinants of health behaviour clusters in survivors only (adjusted multinomial logistic regression model).

| Cluster D1 ‘risk-avoiding’ ( n =352) | Cluster D2 ‘moderate drinking’ ( n =327) | Cluster D3 ‘risk-taking’ ( n =114) | Cluster D4 ‘smoking’ ( n =42) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | P -value b | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 0.33 | (0.23–0.47) | 0.17 | (0.10–0.28) | 0.33 | (0.16–0.67) | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Leukaemia | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.122 | |||

| Lymphoma | 0.74 | (0.46–1.19) | 1.13 | (0.61–2.09) | 0.91 | (0.33–2.51) | ||

| CNS tumour | 0.38 | (0.20–0.77) | 0.26 | (0.09–0.76) | 0.55 | (0.16–1.96) | ||

| Other solid tumoursc | 0.83 | (0.55–1.25) | 0.72 | (0.40–1.31) | 1.04 | (0.42–2.54) | ||

| Therapy | ||||||||

| Surgery only | 2.08 | (1.02–4.24) | 2.94 | (1.13–7.63) | 5.77 | (1.55–21.4) | 0.003 | |

| Chemotherapy, but no radiotherapy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Any radiotherapy | 0.77 | (0.51–1.16) | 0.59 | (0.33–1.06) | 1.47 | (0.60–3.62) | ||

| BMT | 0.85 | (0.48–1.50) | 0.55 | (0.23–1.28) | 3.60 | (1.27–10.2) | ||

| Relapse | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.064 | |||

| Yes | 0.52 | (0.32–0.87) | 0.57 | (0.27–1.18) | 0.56 | (0.21–1.47) | ||

| Migration background | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 0.71 | (0.47–1.08) | 0.76 | (0.42–1.38) | 2.60 | (1.23–5.49) | ||

| Income | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 0.34 | (0.22–0.66) | 0.25 | (0.10–0.60) | 0.18 | (0.04–0.85) | 0.001 | |

| 0–3000 CHF | 0.72 | (0.48–1.10) | 0.86 | (0.48–1.54) | 0.92 | (0.40–2.14) | ||

| 3001–6000 CHF | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| >6000 CHF | 2.02 | (1.09–7.67) | 1.89 | (0.61–5.82) | 0.94 | (0.10–8.69) | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Compulsory schooling | 0.43 | (0.21–0.89) | 0.74 | (0.31–1.79) | 1.69 | (0.59–4.85) | 0.102 | |

| Vocational training | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Upper secondaryd | 1.22 | (0.83–1.80) | 1.14 | (0.67–1.96) | 0.75 | (0.31–1.80) | ||

| University | 1.44 | (0.73–2.81) | 0.76 | (0.26–2.22) | 0.33 | (0.04–2.86) | ||

| Parent’s education e | ||||||||

| Compulsory schooling | 1.08 | (0.57–2.06) | 0.73 | (0.27–1.99) | 2.51 | (0.93–6.80) | 0.483 | |

| Vocational training | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Higher secondaryd | 1.27 | (0.86–1.87) | 0.99 | (0.57–1.71) | 1.97 | (0.84–4.64) | ||

| University | 1.76 | (0.97–3.17) | 1.83 | (0.83–4.03) | 1.05 | (0.20–5.46) | ||

Abbreviations: BMT=bone marrow transplantation; CHF=Swiss Francs; CI=confidence interval; CNS=central nervous system; CHF=Swiss Francs; OR=odds ratio.

Adjusted for all factors listed and age at survey. Reference group for ORs is the ‘risk-avoiding’ Cluster D1, for example, the odds of belonging to Cluster D2 rather than to Cluster D1 (probability of Cluster D2/probability of Cluster D1) among females is 0.33 times that among males.

P-value of likelihood-ratio test.

Includes neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, Wilms tumour, liver tumour, germ cell tumour, epithelial neoplasms, malignant melanomas, unspecified malignant tumours and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Higher secondary education includes high school, teachers training colleges, technical colleges and higher vocational education.

The highest level of education of either father or mother.

In additional analysis (Supplementary Table 4), we investigated whether potential effects of diagnosis and treatment were mediated via education and income (assessed at time of survey) by excluding the latter variables from the regression models. Estimated associations did not change substantially, suggesting that associations between health-behaviour patterns and diagnosis or therapy were not mediated by educational attainment and income.

Discussion

This study used LCA to determine how health behaviours cluster in young adult childhood cancer survivors and controls from the general population. Four health-behaviour clusters were identified: (i) ‘risk-avoiding’ with a healthy behaviour throughout, (ii) ‘moderate drinking’ with a similar profile, but engaging in more exercise and binge drinking, (iii) ‘risk-taking’ engaging in all risk behaviours and (iv) ‘smoking’ with a risk profile comparable with ‘risk-taking’, but low alcohol consumption. Fewer survivors than controls were part of the ‘smoking’ cluster, but more fell into the ‘moderate-drinking’ cluster. A considerable proportion, comparable to that in the general population (14%), engaged in multiple health-compromising behaviours.

Comparison with other health behaviour studies in the general population

Several authors have reported evidence for the clustering of health behaviour in the general population, including in children, adults and the elderly (Karvonen et al, 2000; Chiolero et al, 2006; Poortinga, 2007; Schneider et al, 2009; Sutfin et al, 2009; Huh et al, 2011). Our results are consistent with findings of a previous analysis of risk behaviours in the general Swiss population showing that, with increasing number of cigarettes, smokers engage less in leisure time physical activity, eat less fruits/vegetables and drink more alcohol (Chiolero et al, 2006). Determinants of multiple-risk behaviours in these studies were male gender and lower social class (Chiolero et al, 2006; Poortinga, 2007; Schneider et al, 2009). In agreement with these findings, we found that male gender was also associated with all three clusters involving risk behaviours. As in a previous study using data from the SCCSS (Rebholz et al, 2012), we found that high income and education were associated with alcohol consumption patterns. In student populations, increased alcohol use has previously been reported (O’Malley and Johnston, 2002), particularly among better-off students (Wicki et al, 2010). Students consume alcohol mostly for social and enhancement motives during social gatherings (Wicki et al, 2010). These may include gatherings in connection with sporting activities. Pupils engaging in a lot of sports more often reported episodes of drunkenness in Switzerland (Annaheim et al, 2006). In agreement with a study of Schneider et al, 2009 in a population 50 years plus, we found that the ‘smoking’ cluster contained many individuals with lower education and a migration background.

Comparison with health-behaviour studies in childhood cancer survivors

Several authors have compared single behaviours between survivors and healthy adults. They usually found less engagement in health-compromising behaviour among survivors, particularly smoking (Emmons et al, 2002; Carswell et al, 2008; Frobisher et al, 2008) and alcohol consumption (Carswell et al, 2008; Lown et al, 2008; Frobisher et al, 2010; Rebholz et al, 2012). Rather than focusing on single behaviours, we chose a multiple behaviour approach. This allowed, for instance, to identify the group of ‘risk-takers’, who engage in various unhealthy activities while neglecting healthy behaviours, and to show that this group is as prevalent among survivors as in the general population. This would not have been evident from a simple univariate comparison of health behaviours between survivors and controls.

Few other studies have looked at engagement in multiple health behaviours of childhood cancer survivors, finding that behaviours were correlated with each other (Mulhern et al, 1995; Larcombe et al, 2002; Butterfield et al, 2004). Butterfield et al, 2004 created a risk factor variable out of five behaviours and found that the majority (92%) of survivors who were enroled in a smoking cessation trial engaged in other health-compromising behaviours. Larcombe et al, 2002 used principal component analysis to create a health-behaviour index based on smoking, drinking, recreational drug use, diet, exercise and sun care, ranging from ‘most healthy’ to ‘least healthy’. The behaviour patterns ‘risk-avoiding’ and ‘risk-taking’ identified in our study may correspond to the ends of this spectrum. However, our approach using LCA identified two additional qualitatively distinct patterns ‘moderate drinking’ and ‘smoking’, which do not easily fit into a continuous spectrum.

Strengths and limitations

The SCCSS is a national population-based survey of childhood cancer survivors with a response rate of 72% that well represents young adult childhood cancer survivors in Switzerland. Questions on health behaviours originated from the SHS and were assessed in the SCCSS and SHS 2007 in the same study period. We used an objective method (LCA) to derive health-behaviour patterns from data on a set of pre-specified behaviour variables.

Several limitations should be considered. Health behaviours were based on self-report in both surveys and were, because of restrictions in length of the questionnaire, limited in detail. Differences in the survey methods (paper questionnaires in the SCCSS and telephone interviews in the SHS) may have influenced replies. ‘Wish bias’, that is, the tendency to underreport health compromising or overreport socially desirable behaviours (Wynder et al, 1990), may have differentially affected replies in survivors and controls. Finally, results of the LCA depend on the selection of variables included in the models. A different selection of variables might have resulted in somewhat different patterns of health behaviours.

Implications for clinical practice

Our finding that the ‘risk-avoiding’ and ‘risk-taking’ behaviour patterns were equally prevalent in survivors and controls suggests that the experience of having had childhood cancer does not change future health behaviour in the majority of survivors. However, the higher proportion ‘moderate drinkers’ compared with ‘smokers’ in survivors might represent a shift away from smoking towards increased alcohol consumption in some. It is possible that survivors are more aware of the health-compromising effect of tobacco than of alcohol. In clinical guidelines on follow-up, care counselling against smoking is recommended (Hewitt et al, 2003; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2004; Hewitt et al, 2005; United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group, 2005), while whereas alcohol is rarely mentioned (Hewitt et al, 2003; Children’s Oncology Group, 2008).

Few health interventions have yet been conducted in childhood cancer survivors (Clarke and Eiser, 2007; San Juan et al, 2011). Our study suggests that there is a need for targeted health interventions by showing that a significant proportion of cancer survivors readily engaged in multiple harmful activities. Given the increased vulnerability of childhood cancer survivors for chronic diseases and late mortality, this is a reason for concern (Hewitt et al, 2003; Oeffinger et al, 2006; Reulen et al, 2010). Engaging in multiple risk behaviours simultaneously can have synergistic detrimental effects on health (Mokdad et al, 2005), and health interventions should therefore primarily target survivors showing multiple-risk behaviour pattern. Multicomponent health interventions may help these survivors to adopt a healthy lifestyle (Prochaska, 2008). Conversely improvement of single behaviours may serve as a gateway: increasing physical activity and a healthier diet could, in turn, increase motivation and confidence for reducing smoking and alcohol consumption habits (Butterfield et al, 2004). Such an intervention might also benefit the small group of survivors who were allocated to the ‘smoking’ pattern, but not the ‘moderate drinkers’.

Routine assessment of health behaviours and targeted counselling should be included in long-term follow-up for childhood cancer survivors. In previous studies, survivors have expressed interest in receiving lifestyle counselling, in particular for diet and physical activity (Demark-Wahnefried et al, 2005b; Zebrack, 2008), and follow-up care appointments may provide opportunities for teachable moments (Demark-Wahnefried et al, 2005a). Special attention should be given to male patients, to survivors from immigrant families, who are at particular risk of smoking, but also to survivors with a high educational attainment, who are at greater risk of increased alcohol consumption including binge drinking. Because of their high risk of late effects, survivors after BMT should be regularly seen in follow-up appointments, and risky behaviours should be strongly discouraged.

In conclusion, although engaging in health protective behaviour is more common and smoking less common in childhood cancer survivors than among young adults from the general population, a comparable proportion of young adults in both populations engage in multiple health-compromising activities. As childhood cancer survivors remain a vulnerable population, targeted health interventions are needed for this multiple risk-taking group.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swiss Cancer League (Grant No KLS-01605-10-2004 and KLS-2215-02-2008), the Wyeth Foundation for the Health of Children and Adolescents, and the Foundation for the Fight against Cancer. Gisela Michel and Claudia Kuehni were funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (GM: Ambizione Grant PZ00P3_121682 and PZ00P3_141722; CK: PROSPER Grant 3233-069348), Ben Spycher by Asthma UK (Grant 07/048) and Cornelia Rebholz by a scholarship of the Bernese Cancer League.

Appendix

The Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group (SPOG): Dr med R Angst, Aarau; Professor Dr med M Paulussen, Professor Dr med T Kühne, Basel; Professor Dr med A Hirt, Professor Dr med K Leibundgut, Bern; PD Dr med AH Ozsahin, Geneva; PD Dr med M Beck Popovic, Lausanne; Dr med L Nobile Buetti, Locarno; Dr med Pierluigi Brazzola, Bellinzona; Dr med U Caflisch, Lucerne; Dr med J Greiner, Dr med H Hengartner, St Gallen; Professor Dr med M Grotzer, Professor Dr med F Niggli, Zürich.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Annaheim B, Schmid H, Kuntsche E (2006) Sport und Bewegung von 11- bis 16 -jährigen Schülerinnen und Schülern in der Schweiz. Schweizerische Fachstelle für Alkohol- und andere Drogenprobleme: Lausanne [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Mertens AC (2009) Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27(14): 2328–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauld C, Toumbourou JW, Anderson V, Coffey C, Olsson CA (2005) Health-risk behaviours among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45(5): 706–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Statistik (2008) Schweizerische Gesundheitsbefragung 2007—Erste Ergebnisse. Bundesamt für Statistik: Neuchâtel [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield RM, Park ER, Puleo E, Mertens A, Gritz ER, Li FP, Emmons K (2004) Multiple risk behaviors among smokers in the childhood cancer survivors study cohort. Psychooncology 13(9): 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell K, Chen Y, Nair RC, Shaw AK, Speechley KN, Barrera M, Maunsell E (2008) Smoking and binge drinking among Canadian survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers: a comparative, population-based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51(2): 280–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) The Burden Of Chronic Diseases And Their Risk Factors: National And State Perspectives 2004. US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Oncology Group (2008) Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. www.survivorshipguidelines.org (accessed 21 March 2010)

- Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, Cornuz J (2006) Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: a population-based survey. Prev Med 42(5): 348–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SA, Eiser C (2007) Health behaviours in childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer 43(9): 1373–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Zhu L, Finnegan L, Steen BD, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Oeffinger KC (2011) Survivor profiles predict health behavior intent: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Psychooncology 21(5): 469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM (2005a) Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(24): 5814–5830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW (2008) Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 22(2): 319–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried W, Werner C, Clipp EC, Guill AB, Bonner M, Jones LW, Rosoff PM (2005b) Survivors of childhood cancer and their guardians. Cancer 103(10): 2171–2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K, Li FP, Whitton J, Mertens AC, Hutchinson R, Diller L, Robison LL for the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (2002) Predictors of smoking initiation and cessation among childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 20(6): 1608–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Stevens MC, Hawkins MM (2010) Extent of alcohol consumption among adult survivors of childhood cancer: the British childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19(5): 1174–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frobisher C, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, Reulen RC, Taylor AJ, Eiser C, Stevens MC, Hawkins MM (2008) Extent of smoking and age at initiation of smoking among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(15): 1068–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Demark-Wahnefried W (2009) Health behaviors influence cancer survival. J Clin Oncol 27(12): 1930–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins MM, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Taylor AJ, Stevens MC, Jenney M (2008) The British childhood cancer survivor study: objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50: 1018–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall EL (2005) From Cancer Patient To Cancer Survivors: Lost In Transition. National Academies Press: Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV, National Research Council (2003) Childhood Cancer Survivorship. Improving Care And Quality Of Life. National Cancer Policy Board: Washington, DC [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Lewis DR, Eisner MP, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK (2009) Seer Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006. National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA [Google Scholar]

- Huh J, Riggs NR, Spruijt-Metz D, Chou CP, Huang Z, Pentz M (2011) Identifying patterns of eating and physical activity in children: a latent class analysis of obesity risk. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19(3): 652–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karvonen S, Abel T, Calmonte R, Rimpela A (2000) Patterns of health-related behaviour and their cross-cultural validity—a comparative study on two populations of young people. Soz Praventivmed 45(1): 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N (2008) Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med 5(1): 0039–0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehni CE, Rueegg CS, Michel G, Rebholz CE, Strippoli MP, Niggli FK, Egger M, von der Weid NX (2011) Cohort profile: The Swiss childhood cancer survivor study. Int J Epidemiol doi:10.1093/ije/dyr142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Larcombe I, Mott M, Hunt L (2002) Lifestyle behaviours of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer 87(11): 1204–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW (1968) Latent Structure Analysis. Houghton Mifflin: Boston [Google Scholar]

- Lown EA, Goldsby R, Mertens AC, Greenfield T, Bond J, Whitton J, Korcha R, Robison LL, Zeltzer LK (2008) Alcohol consumption patterns and risk factors among childhood cancer survivors compared to siblings and general population peers. Addiction 103(7): 1139–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D (2000) Finite Mixture Models. John Wiley & Sons: New York [Google Scholar]

- Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Neglia JP, Mertens AC, Donaldson SS, Stovall M, Hammond S, Yasui Y, Inskip PD (2009) Second neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer: findings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol 27(14): 2356–2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel G, von der Weid NX, Zwahlen M, Adam M, Rebholz CE, Kuehni CE (2007) The Swiss childhood cancer registry: rationale, organisation and results for the years 2001–2005. Swiss Med Wkly 137(35-36): 502–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (2005) Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. J Am Med Assoc 293(3): 293–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhern RK, Tyc VL, Phipps S, Crom D, Barclay D, Greenwald C, Hudson M, Thompson EI (1995) Health-related behaviors of survivors of childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol 25(3): 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD (2002) Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 14: 23–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, Schwartz CL, Leisenring W, Robison LL (2006) Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355(15): 1572–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga W (2007) The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med 44(2): 124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO (2008) Multiple health behavior research represents the future of preventive medicine. Prev Med 46(3): 281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz CE, Kuehni CE, Strippoli MP, Rueegg CS, Michel G, Hengartner H, Bergstraesser E, von der Weid NX (2012) Alcohol consumption and binge drinking in young adult childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 58(2): 256–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Stiller CA, Jenney ME, Skinner R, Stevens MC, Hawkins MM (2010) Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 304(2): 172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, Li FP, Meadows AT, Mulvihill JJ, Neglia JP, Nesbit ME, Packer RJ, Potter JD, Sklar CA, Smith MA, Stovall M, Strong LC, Yasui Y, Zeltzer LK (2002) Study design and cohort characteristics of the childhood cancer survivor study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol 38(4): 229–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Juan AF, Wolin K, Lucia A (2011) Physical activity and pediatric cancer survivorship. Recent Results Cancer Res 186: 319–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Huy C, Schuessler M, Diehl K, Schwarz S (2009) Optimising lifestyle interventions: identification of health behaviour patterns by cluster analysis in a German 50+ survey. Eur J Public Health 19(3): 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2004) Long term follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer. A national clinical guideline. No. 76 Vol. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign76.pdf (accessed 1 November 2010)

- Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S (2008) Latent variable modelling. Stat Methods Med Res 17(1): 3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, Kaatsch P (2005) International classification of childhood cancer. 3rd Edn. Cancer 103(7): 1457–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, Reboussin BA, McCoy TP, Wolfson M (2009) Are college student smokers really a homogeneous group? a latent class analysis of college student smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 11(4): 444–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group (2005) Therapy based long-term follow-up. In A practice statementSkinner R, Wallace WH, Levitt GA (eds) 2nd Edition United Kingdom children’s cancer study group, Late effects group: UK [Google Scholar]

- von der Weid N, Beck D, Caflisch U, Feldges A, Wyss M, Wagner HP (1996) Standardized assessment of late effects in long-term survivors of childhood cancer in Switzerland. Int J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 3: 483–490 [Google Scholar]

- White J, Flohr JA, Winter SS, Vener J, Feinauer LR, Ransdell LB (2005) Potential benefits of physical activity for children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Pediatr Rehabil 8(1): 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicki M, Kuntsche E, Gmel G (2010) Drinking at European Universities? A review of students’ alcohol use. Addict Behav 35(11): 913–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder EL, Higgins IT, Harris RE (1990) The wish bias. J Clin Epidemiol 43(6): 619–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B (2008) Information and service needs for young adult cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 16(12): 1353–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.