Regulatory T-cells (Treg) have emerged as a crucial cellular checkpoint acting to prevent potentially harmful immune responses. Due to its highly diverse activities, regulating the immune system requires more than general suppression. Particularly, during the developing immune response to infection, Treg need to balance the host reaction to achieve both an effective response against the invading pathogen as well as to prevent immunopathology from excessive or inappropriate activity. In this opinion article we discuss the dual roles of IL-2 as both a key inducer of Treg activity and also a target of Treg control during the acute phase of infection. We propose a model in which Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells dynamically “measure” IL-2 availability and restrict its access to effector T-cells, thereby controlling differentiation of these useful but potentially harmful cells.

CD4+ T-lymphocytes play a central role in orchestrating immune responses by modifying the functionality of other immune cells and guiding the qualitative features of a response to one optimal for resisting a particular microorganism. Besides augmenting both innate and adaptive immune responses, CD4+ T-cells limit excessive immune activation and immunopathology during infections. Among CD4+ T-cells, Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells (Treg) are essential for the maintenance of peripheral tolerance (Kim et al., 2007; Lahl et al., 2007). These cells also modulate the responses to pathogens (Belkaid and Tarbell, 2009). A plethora of mechanisms for how Treg exert their function have been suggested (Shevach, 2009; Josefowicz et al., 2012). However, there is still an ongoing debate as to which functions of Treg are essential under which circumstances. Likely, Treg function can be attuned to specific conditions and distinct “rules” govern Treg behavior in the steady-state versus inflammatory environments, secondary lymphoid (SLO) versus peripheral organs, developing versus ongoing immune responses, or acute versus chronic infections, for example. In this article we focus on the function of Treg in the SLO during a developing acute infection and, although several cytokines are relevant, we concentrate on IL-2 as a central platform that enables effective immune control, as it (1) links activation of effector and regulatory responses, (2) establishes a feed-back loop for T-cell expansion, and (3) allows control over T-cell differentiation and fate decisions, preserving memory formation.

IL-2 is a Central Cytokine for T-Cell Activation

IL-2, originally discovered as a mitogenic factor for T-cells, is bound as a quaternary complex with CD25 (IL2Rα-chain), CD122 (IL2Rβ-chain), and CD132 (common γ-chain). The α/β-heterodimer facilitates IL-2 capture with high affinity and, further stabilized by the γ-chain, forms a very stable complex which is terminated via receptor internalization rather than ligand dissociation (Smith, 2006). Upon activation by TCR interactions and additional co-stimulation via CD80/CD86, conventional T-cells (Tconv) produce IL-2 and upregulate CD25 expression, which enhances IL-2 capture and consequently IL-2 signaling, further promoting CD25 expression, T-cell activation, and proliferation. This feed-forward loop can lead to activation-induced cell death, but highly activated, proliferating T-cells also undergo apoptosis when acutely deprived of IL-2 signals. Therefore, IL-2 is a master regulator of T-cell activation, proliferation, and death, excellently reviewed in Malek and Castro (2010), Boyman and Sprent (2012).

Activation of Treg Through IL-2: Anticipation and Sensing of Effector Responses

In contrast to conventional T-cells (Tconv), Treg constitutively express CD25 (Sakaguchi et al., 1995) and have STAT5 phosphorylation in the steady-state, arguing for continuous or high frequency intermittent IL-2 signaling in the absence of infection. Indeed, IL-2 signals seem to be pivotal for Treg survival because animals that lack IL-2, CD25, or CD122 are largely devoid of peripheral Treg and suffer from severe autoimmunity (Sadlack et al., 1993; Suzuki et al., 1995; Willerford et al., 1995; Fontenot et al., 2005). Treg do not produce IL-2 themselves when stimulated through the TCR and therefore rely on paracrine IL-2 for their maintenance. Tconv produce IL-2 upon activation and then gradually upregulate CD25. Since Treg constitutively express CD25, they can sense and signal via IL-2 as soon as it is produced, assuming that these Treg are within suitable proximity to the cytokine secreting cells. Because IL-2 signaling further upregulates CD25, Treg can even increase their ability to capture IL-2 as compared to Tconv which need to initiate CD25 expression post TCR-mediated activation (Feinerman et al., 2010). Indeed, it has been shown in vivo that Treg are the first cells to respond to IL-2 upon antigenic challenge of Tconv (O’Gorman et al., 2009). As the amount of IL-2 produced by T-cells correlates with the extent of co-stimulation from DC in vitro (Shahinian et al., 1993) and in vivo (Kastenmuller et al., 2011), it might reflect the magnitude of pathogen burden and the extent of innate stimulation. Therefore, Treg “sense” the initiation of an adaptive immune response in a qualitative and potentially quantitative manner when responding to IL-2 signals derived from adaptive effectors.

Treg Control the Availability of IL-2

Given the relative abundance of Treg in SLO, where adaptive responses are initiated and IL-2 is being produced, it seems likely that the “sensing” of IL-2 by Treg consumes a significant amount of the totally available IL-2. In this scenario, the mere presence of Treg could reduce IL-2 availability and limit Teff responses, without a need for active regulation (cytokine-sink model). Indeed, the presence of Treg leads to substantial competition for IL-2, resulting in impaired proliferation of Teff cells in vitro. Competition was further demonstrated in vivo, with a primary effect on the survival of Teff and not on their proliferation (Pandiyan et al., 2007; Kastenmuller et al., 2011). Treg also control IL-2 production (Thornton and Shevach, 1998), either by directly acting on T-cells (Bodor et al., 2007; Vaeth et al., 2011) or indirectly, through DC (Onishi et al., 2008). The latter concept is based on in vitro evidence of a positive correlation between IL-2 production by Teff, the strength of ConA stimulation, and the amount of CD28 expression (Shahinian et al., 1993). Treg express significant levels of surface CTLA-4 on their surface and this molecule can directly block co-stimulatory molecules and CD28-CD80/86-interactions, or, via trans endocytosis, modulate the amount of CD80/86 that is displayed by DC (Wing et al., 2008; Qureshi et al., 2011). Importantly, the amount of CTLA-4 expressed on Treg is again regulated by IL-2 signals. Consequently, Treg control the level of co-stimulation through CD80/CD86 surface expression not only during steady-state (Schildknecht et al., 2010), but, importantly, also during highly inflammatory processes such as viral infection (Kastenmuller et al., 2011).

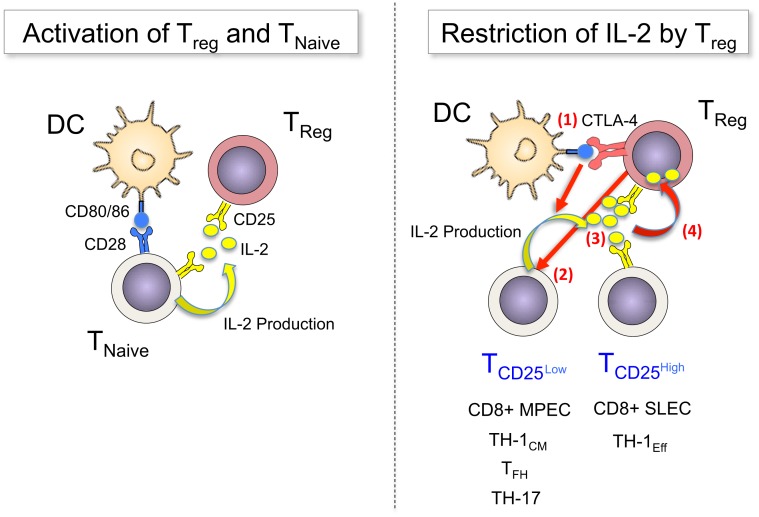

Therefore, DC appear to constitute a platform on which both stimulation and regulation of conventional T-cells is executed, with IL-2 being a central mediator that activates both Teff and Treg. Feed-back loops involving the constitutive high levels of CD25 on Tregs and the IL-2-promoted upregulation of CTLA-4 on these cells operate in concert to restrict IL-2 availability to activated Teff, controlling their expansion, differentiation, and survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treg sense IL-2 early during immune responses and restrict cytokine availability to control T-cell fates. Left panel: TCR signals (not depicted) and co-stimulatory signals via CD80/86 activate naïve T-cells to upregulate CD25 and produce IL-2. Treg have constitutive expression of CD25, which enables them to “sense” early (d0) production of IL-2 and become activated. Right panel: Once activated T-cells divide, they become heterogeneous for CD25 expression (d2–4): a fraction of cells downregulates CD25, avoiding further IL-2 signals – and potentially regulation through Treg – in order to differentiate into long-lived memory cells (MPEC or TH-1CM), follicular helper cells or TH-17 cells, or they maintain CD25 expression for prolonged IL-2 signals to undergo terminal effector differentiation. Treg can balance this differentiation processes by regulating the availability of IL-2 via multiple mechanisms, among them (1) the blocking and reduction of CD80/86 via CTLA-4, (2) the direct inhibition of IL-2 production by T-cells, (3) the competition for IL-2, and (4) the consumption and degradation of IL-2.

Treg Selectively Regulate Effector T-Cell Responses but Preserve Memory Development

Recently, the effects of IL-2 during acute infection have been further refined through analysis of the role of this cytokine in the various stages of CD8+ T-cell differentiation. After their initial activation and induction of CD25 expression, a subpopulation of CD8+ T-cells decrease CD25 levels and become unresponsive to further IL-2 signals, and, at the same time, upregulate the IL-7Rα-chain and develop into long-lived memory cells. This is in contrast to T-cells that are exposed to IL-2 for a prolonged period and maintain CD25 expression, undergo enhanced expansion, but differentiate into short-lived effector cells (SLEC) that are prone to apoptosis and severe population contraction after the peak of the response (Kalia et al., 2010; Obar et al., 2010; Pipkin et al., 2010). The recent development of genetic models allowing the specific depletion of Foxp3+ Treg (Kim et al., 2007; Lahl et al., 2007) without blocking IL-2/CD25 interactions (Murakami et al., 2002; Suvas et al., 2003; Toka et al., 2004; Heit et al., 2008) enabled asking whether Treg differentially affect these CD8+ T-cell subpopulations. Indeed, manipulating the numbers of activated Treg in vivo impacted CD25 expression on activated CD8+ T-cells, indicative of altered IL-2 availability. This resulted in specific changes in numbers of SLEC while leaving the memory CD8+ T-cell compartment largely unaltered (Kastenmuller et al., 2011; McNally et al., 2011). Interestingly, the “window of opportunity” for the regulation of CD8+ T-cell responses by Treg overlapped with the time of CD25 expression on CD8+ T-cells: depletion of Treg cells as late as d2–3 post infection enhanced antigen-specific T-cell numbers in a viral infection model, but depletion later than d5 (when CD8+ T-cells do not express CD25) failed to do so (Kastenmuller et al., 2011). In addition, enhanced expansion of SLEC in the absence of Treg was abrogated through the neutralization of IL-2 (McNally et al., 2011). Therefore, by controlling the availability of IL-2, Treg cells can act as rheostats that balance the differentiation and expansion of pathogen-specific CD8+ effector T-cells. Importantly, by selectively regulating SLEC over memory precursor T-cells, which rapidly seem to become independent of IL-2 signals (d2–3), Treg can limit the extent of acute effector responses without blunting the development of long-lived memory (Kastenmuller et al., 2011). However, once memory is formed and the host is re-challenged with a pathogen, Treg can again control the expansion of secondary effector cells adapted to the extent and requirements of the current infection.

Treg Mediated Restriction of IL-2 as a General Mechanism to Regulate Fate Decisions in T-Cells

Beyond CD8+ T-cells, IL-2 likely serves as a central element that allows Treg to regulate population size and differentiation of T-cells in general. A series of recent studies have established the role of IL-2 in CD4+ T-cell differentiation into TH1, TH2, TH17, and TFH cells (Liao et al., 2011; Boyman and Sprent, 2012). As with CD8+ T-cells discussed above, CD4+ T-cells segregate into CD25high and CD25low cells within the first days of a response to an acute infection, and prolonged IL-2 signals in CD25high cells leads to terminal differentiation and Blimp1 and T-bet upregulation in CD4+ effector cells. In contrast, CD25low cells gave rise to long-lived CXCR5highCCR7highT-betlow precursors of central memory cells, as well as CXCR5highBcl6high follicular T-helper cells (TFH; Choi et al., 2011; Pepper et al., 2011). In line with this, Treg limit the expansion of antiviral CD4+ during acute infection, yet do not influence the generation of neutralizing antibodies (Kastenmuller et al., 2011).

Therefore, by limiting excessive IL-2, Treg might not only blunt Teff response but also ensure the generation of TFH cells and consequently the development of appropriate humoral immunity early during acute infection, as IL-2 signals negatively regulate TFH differentiation (Ballesteros-Tato et al., 2012; Johnston et al., 2012). By restricting IL-2 during acute infection, Treg might additionally enhance mucosal immunity and regeneration (potentially preventing superinfection) through promotion of TH17 generation, because production of this class of effector cells is inhibited by IL-2 (Chen et al., 2011; Pandiyan et al., 2011).

Summary and Perspective

In summary, we propose a model in which IL-2 availability is a central factor that controls the magnitude and shapes the character of adaptive immune responses. Treg control access of other T-cells to this crucial cytokine by limiting its production through interference with co-stimulatory molecule availability on DC, as well as by reducing its abundance through consumption. Importantly, this does not act to simply blunt the overall immune response but selectively impacts on T-cell fates that require larger amounts of IL-2. In contrast, other T-cell subpopulations, such as memory-precursors or TFH, are not suppressed, allowing for the generation of cellular and humoral immunological memory to protect the host from future pathogen encounters (Figure 1). Treg are therefore not merely immunosuppressive, they actively participate in guiding the differentiation and fate decisions of other T-cells by regulating the availability of IL-2 in SLO. In this regard, Treg controlling IL-2 availability remind us of the three Moirai (the incarnation of destiny in greek mythology) who controlled the thread of life and thereby directed the fate of individuals.

In addition to this early regulation of effector responses through IL-2, Treg can undergo functional specialization that parallels the differentiation of conventional CD4+ T-cells in terms of transcription factor usage and expression of chemokine receptors important for homing to peripheral sites (Chaudhry et al., 2009; Koch et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2011; Linterman et al., 2011). This differentiation might facilitate Treg control of fully differentiated effector cells in infected tissues, which is likely to involve mechanisms distinct from regulating or competing for IL-2 (Soper et al., 2007), such as the production of immunosuppressive cytokines (Rubtsov et al., 2008) or cytotoxic molecules (Cao et al., 2007; Loebbermann et al., 2012).

Based on the emerging picture of selective control of effector T-cell fates, we speculate that interfering with Treg function will help to optimize short-term immunotherapeutic approaches, but might be less promising to increase the efficacy of prophylactic vaccines aiming at the induction of long-term memory through T- and B-cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, NIH, and DFG Ka 3091/1-1 to Wolfgang Kastenmuller. We would like to thank Dr. Ronald N. Germain for providing critical discussions, important input for this manuscript and great mentorship.

References

- Ballesteros-Tato A., Leon B., Graf B. A., Moquin A., Adams P. S., Lund F. E., Randall T. D. (2012). Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity 36, 847–856 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y., Tarbell K. (2009). Regulatory T cells in the control of host-microorganism interactions (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 551–589 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor J., Fehervari Z., Diamond B., Sakaguchi S. (2007). ICER/CREM-mediated transcriptional attenuation of IL-2 and its role in suppression by regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 884–895 10.1002/eji.200636510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyman O., Sprent J. (2012). The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 180–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Cai S. F., Fehniger T. A., Song J., Collins L. I., Piwnica-Worms D. R., Ley T. J. (2007). Granzyme B and perforin are important for regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of tumor clearance. Immunity 27, 635–646 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry A., Rudra D., Treuting P., Samstein R. M., Liang Y., Kas A., Rudensky A. Y. (2009). CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science 326, 986–991 10.1126/science.1172702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Haines C. J., Gutcher I., Hochweller K., Blumenschein W. M., McClanahan T., Hammerling G., Li M. O., Cua D. J., McGeachy M. J. (2011). Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin-2. Immunity 34, 409–421 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. S., Kageyama R., Eto D., Escobar T. C., Johnston R. J., Monticelli L., Lao C., Crotty S. (2011). ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity 34, 932–946 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y., Tanaka S., Chu F., Nurieva R. I., Martinez G. J., Rawal S., Wang Y. H., Lim H., Reynolds J. M., Zhou X. H., Fan H. M., Liu Z. M., Neelapu S. S., Dong C. (2011). Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat. Med. 17, 983–988 10.1038/nm.2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinerman O., Jentsch G., Tkach K. E., Coward J. W., Hathorn M. M., Sneddon M. W., Emonet T., Smith K. A., Altan-Bonnet G. (2010). Single-cell quantification of IL-2 response by effector and regulatory T cells reveals critical plasticity in immune response. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 437. 10.1038/msb.2010.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot J. D., Rasmussen J. P., Gavin M. A., Rudensky A. Y. (2005). A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1142–1151 10.1038/ni1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit A., Gebhardt F., Lahl K., Neuenhahn M., Schmitz F., Anderl F., Wagner H., Sparwasser T., Busch D. H., Kastenmuller K. (2008). Circumvention of regulatory CD4(+) T cell activity during cross-priming strongly enhances T cell-mediated immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1585–1597 10.1002/eji.200737966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R. J., Choi Y. S., Diamond J. A., Yang J. A., Crotty S. (2012). STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 209, 243–250 10.1084/jem.20111174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz S. Z., Lu L. F., Rudensky A. Y. (2012). Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 531–564 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V., Sarkar S., Subramaniam S., Haining W. N., Smith K. A., Ahmed R. (2010). Prolonged interleukin-2R alpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity 32, 91–103 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmuller W., Gasteiger G., Subramanian N., Sparwasser T., Busch D. H., Belkaid Y., Drexler I., Germain R. N. (2011). Regulatory T cells selectively control CD8+ T cell effector pool size via IL-2 restriction. J. Immunol. 187, 3186–3197 10.4049/jimmunol.1101649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M., Rasmussen J. P., Rudensky A. Y. (2007). Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat. Immunol. 8, 191–197 10.1038/ni1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. A., Tucker-Heard G., Perdue N. R., Killebrew J. R., Urdahl K. B., Campbell D. J. (2009). The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 10, 595–602 10.1038/nrg2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahl K., Loddenkemper C., Drouin C., Freyer J., Arnason J., Eberl G., Hamann A., Wagner H., Huehn J., Sparwasser T. (2007). Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induces a scurfy-like disease. J. Exp. Med. 204, 57–63 10.1084/jem.20061852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W., Lin J. X., Leonard W. J. (2011). IL-2 family cytokines: new insights into the complex roles of IL-2 as a broad regulator of T helper cell differentiation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 598–604 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linterman M. A., Pierson W., Lee S. K., Kallies A., Kawamoto S., Rayner T. F., Srivastava M., Divekar D. P., Beaton L., Hogan J. J., Fagarasan S., Liston A., Smith K. G., Vinuesa C. G. (2011). Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat. Med. 17, 975–982 10.1038/nm.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebbermann J., Thornton H., Durant L., Sparwasser T., Webster K. E., Sprent J., Culley F. J., Johansson C., Openshaw P. J. (2012). Regulatory T cells expressing granzyme B play a critical role in controlling lung inflammation during acute viral infection. Mucosal Immunol. 5, 161–172 10.1038/mi.2011.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek T. R., Castro I. (2010). Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity 33, 153–165 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally A., Hill G. R., Sparwasser T., Thomas R., Steptoe R. J. (2011). CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control CD8+ T-cell effector differentiation by modulating IL-2 homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7529–7534 10.1073/pnas.1101825108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Sakamoto A., Bender J., Kappler J., Marrack P. (2002). CD25+CD4+ T cells contribute to the control of memory CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 8832–8837 10.1073/pnas.132254399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obar J. J., Molloy M. J., Jellison E. R., Stoklasek T. A., Zhang W., Usherwood E. J., Lefrancois L. (2010). CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 193–198 10.1073/pnas.0909945107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gorman W. E., Dooms H., Thorne S. H., Kuswanto W. F., Simonds E. F., Krutzik P. O., Nolan G. P., Abbas A. K. (2009). The initial phase of an immune response functions to activate regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 183, 332–339 10.4049/jimmunol.0900691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi Y., Fehervari Z., Yamaguchi T., Sakaguchi S. (2008). Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells preferentially form aggregates on dendritic cells in vitro and actively inhibit their maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10113–10118 10.1073/pnas.0711106105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiyan P., Conti H. R., Zheng L., Peterson A. C., Mathern D. R., Hernandez-Santos N., Edgerton M., Gaffen S. L., Lenardo M. J. (2011). CD4(+)CD25(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote Th17 cells in vitro and enhance host resistance in mouse Candida albicans Th17 cell infection model. Immunity 34, 422–434 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiyan P., Zheng L., Ishihara S., Reed J., Lenardo M. J. (2007). CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1353–1362 10.1038/ni1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper M., Pagan A. J., Igyarto B. Z., Taylor J. J., Jenkins M. K. (2011). Opposing signals from the Bcl6 transcription factor and the interleukin-2 receptor generate T helper 1 central and effector memory cells. Immunity 35, 583–595 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipkin M. E., Sacks J. A., Cruz-Guilloty F., Lichtenheld M. G., Bevan M. J., Rao A. (2010). Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity 32, 79–90 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi O. S., Zheng Y., Nakamura K., Attridge K., Manzotti C., Schmidt E. M., Baker J., Jeffery L. E., Kaur S., Briggs Z., Hou T. Z., Futter C. E., Anderson G., Walker L. S., Sansom D. M. (2011). Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science 332, 600–603 10.1126/science.1202947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov Y. P., Rasmussen J. P., Chi E. Y., Fontenot J., Castelli L., Ye X., Treuting P., Siewe L., Roers A., Henderson W. R., Jr., Muller W., Rudensky A. Y. (2008). Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity 28, 546–558 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlack B., Merz H., Schorle H., Schimpl A., Feller A. C., Horak I. (1993). Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell 75, 253–261 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. (1995). Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155, 1151–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildknecht A., Brauer S., Brenner C., Lahl K., Schild H., Sparwasser T., Probst H. C., Van Den Broek M. (2010). FoxP3+ regulatory T cells essentially contribute to peripheral CD8+ T-cell tolerance induced by steady-state dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 199–203 10.1073/pnas.0910620107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahinian A., Pfeffer K., Lee K. P., Kundig T. M., Kishihara K., Wakeham A., Kawai K., Ohashi P. S., Thompson C. B., Mak T. W. (1993). Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28-deficient mice. Science 261, 609–612 10.1126/science.7688139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach E. M. (2009). Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity 30, 636–645 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. A. (2006). The structure of IL2 bound to the three chains of the IL2 receptor and how signaling occurs. Med. Immunol. 5, 3. 10.1186/1476-9433-5-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper D. M., Kasprowicz D. J., Ziegler S. F. (2007). IL-2Rbeta links IL-2R signaling with Foxp3 expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 1817–1826 10.1002/eji.200737101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvas S., Kumaraguru U., Pack C. D., Lee S., Rouse B. T. (2003). CD4+CD25+ T cells regulate virus-specific primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 198, 889–901 10.1084/jem.20030171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Kundig T. M., Furlonger C., Wakeham A., Timms E., Matsuyama T., Schmits R., Simard J. J., Ohashi P. S., Griesser H., Taniguchi T., Paige C. J., Mak T. W. (1995). Deregulated T cell activation and autoimmunity in mice lacking interleukin-2 receptor beta. Science 268, 1472–1476 10.1126/science.7770771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A. M., Shevach E. M. (1998). CD4+ CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J. Exp. Med. 188, 287–296 10.1084/jem.188.2.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toka F. N., Suvas S., Rouse B. T. (2004). CD4+ CD25+ T cells regulate vaccine-generated primary and memory CD8+ T-cell responses against herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 78, 13082–13089 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13082-13089.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth M., Gogishvili T., Bopp T., Klein M., Berberich-Siebelt F., Gattenloehner S., Avots A., Sparwasser T., Grebe N., Schmitt E., Hunig T., Serfling E., Bodor J. (2011). Regulatory T cells facilitate the nuclear accumulation of inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) and suppress nuclear factor of activated T cell c1 (NFATc1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 2480–2485 10.1073/pnas.1009463108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willerford D. M., Chen J., Ferry J. A., Davidson L., Ma A., Alt F. W. (1995). Interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain regulates the size and content of the peripheral lymphoid compartment. Immunity 3, 521–530 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90180-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing K., Onishi Y., Prieto-Martin P., Yamaguchi T., Miyara M., Fehervari Z., Nomura T., Sakaguchi S. (2008). CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science 322, 271–275 10.1126/science.1160062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Chaudhry A., Kas A., Deroos P., Kim J. M., CHU T. T., Corcoran L., Treuting P., Klein U., Rudensky A. Y. (2009). Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature 458, 351–356 10.1038/nature07856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]