Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) isa chronic pain condition characterized by pain during joint useas well aspain at rest (i.e., ongoing pain). Although injection of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)into the intra-articular space of the rodent knee is a well established model of OA pain that is characterized by changes in weight bearing and hypersensitivity to tactile and thermal stimuli, it is not known if this procedure elicits ongoing pain. Further, the time-course and possible underlying mechanisms of these components of pain remain poorly understood. In these studies, we demonstrated the presence ofongoing painin addition to changes in weight bearing and evoked hypersensitivity. Twenty-eight days following MIA injection, spinal clonidine blockedchanges in weight bearing and thermal hypersensitivityand produced place preference indicating that MIA induces ongoing and evoked pain.These findings demonstrate the presence of ongoing pain in this model that is present at a late-time point after MIA allowing for mechanistic investigation.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, ongoing pain, referred pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is characterized by progressive loss of articular cartilage, new bone formation, and synovial proliferation that can result in pain, loss of joint function, and diminished quality of life[1]. Pain is the key complaintfor OA patients,is the driving factor for visiting a primary care physician and why many patients choose to undergo joint replacement surgery[15]. OA pain is often comprised of hyperalgesia, referred pain, and ongoing pain (pain at rest)[13]. Osteoarthritis patients report pain that can be broadly characterized into 2 categories: 1) a dull aching, throbbing pain and 2) shorter episodes of more intense or sharp pain, withreports of intense painbecoming more frequent over time[15, 16]. OA pain progresses over time and has been suggested to reflect3 stages: 1) early OA-characterized by predictable pain usually brought on by a trigger, such asactivity; 2) Mid OA-characterized by the pain becoming more constant and beginning to affect daily activities such as walking and climbing stairs; and 3) advanced OA-characterized by constant dull/aching pain punctuated by short episodes of often unpredictable intense pain that leaves the patient exhausted [16].OA pain is primarily treated with lifestyle changes, followed by pharmacological interventions including acetaminophen, NSAIDS, topical agents, intra-articular injections (e.g. steroids), and with non-pharmacological interventions, such as joint replacement, in cases where patients are not responsive to the pharmacological interventions[7, 8, 22]. A better understanding of mechanisms driving OA-induced pain may lead to treatment options with better efficacy and higher safety profiles forthe chronic treatment that is required for this condition.

Injection of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) into the intra-articular space of the knee is an established and well-characterized preclinical model of osteoarthritis[5, 18, 21, 27]. Intra-articular MIA elicits transient inflammation followed by joint destruction consistent with clinical OA[18, 21].Previous studies using this model have demonstrated that intra-articularMIA results in decreasedweight bearing on the injured limb, movement-evoked pain, and hypersensitivity to acute application of noxious (hyperalgesia) and non-noxious (allodynia) stimulation to the hindpaw, indicating referred pain[6, 17, 27]. However, whether this model of OA elicits non-evoked or “ongoing” pain is not known. We recently demonstrated that relief of nerve-injury induced tonic pain by agents known to alleviate spontaneous pain in patients (e.g. spinal ω-conotoxin and clonidine) serves as negative reinforcement resulting in conditioned place preference (CPP) for a context paired with the drug[20].We hypothesized that this principle could be used to uncover ongoing pain that might be present ininjury states such as MIA-induced OA.Here, we used this assay to demonstrate the presence of ongoing pain.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) rats weighing 275 to 300 g were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All preparations and testing were performed in accordance with the policies and recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain, National Institutes of Health, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Arizona. All behavioral experiments were performed by an experimenter blinded to the treatment conditions. Separate groups of rats were used for each of the behavioral tests described below.

Intrathecal Catheter Implantation and Intra-articular Injection of MIA

Rats had intrathecal catheters implanted for spinal clonidine administration as previously described[19, 28]. Animals with signs of motor weakness or paralysis after surgery (< 10%) were not used. Clonidine (10 μg in 5 μl; Tocris Bioscience) or saline was injected 28 days following MIA injection in a volume of 5 ml, followed by 9 ml saline flush. Drug injection was monitored by movement of an air bubble between the drug and saline. Immediately following implantation of intrathecal catheters, rats were given a single intra-articular injection of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA, Sigma, USA) through the infra-patella ligament of the left knee at a dose of 4.8 mg in 60 μl sterile saline. This dose of MIA was deliberately chosen to model severe OA pain.Control animals were given a single intra-articular injection of equivolume sterile saline.

Tactile thresholds

Tactile sensory thresholds were determined using calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) in logarithmically spaced increments ranging from 0.41 to 15 gm (4–150 N) using the up-down method as previously described[19].

Thermal hyperalgesia

The method of Hargreaves et al. [14] was used to assess paw-withdrawal latency to a thermal nociceptive stimulus as previously described [19]. Baseline latencies were established at 20 sec to allow a sufficient window for the detection of possible hyperalgesia. A maximal cutoff of 30 sec was used to prevent tissue damage.

Assessment of Shift in Weight Bearing

Changes in hind paw weight distribution between the left (MIA) and right (contralateral) limbs were utilized as an index of joint discomfort in the MIA treated knee as previously described. An incapacitance tester (Stoelting)was employed for determination of hind paw weight distribution[19]. The data are normalized as % injured/noninjured weight bearing, such that sensitivity on the injured side is indicated by values<100%, equal weight distribution is indicated by 100%.

Conditioned Place Preference Testing

For analysis of spontaneous pain, rats received conditioning with spinal clonidinesimilar to the previously describedsingle conditioning trial protocol[20]. All rats underwent a 3 day habituation, in which rats were placed in the automated CPP boxes with access to all chambers for 30 min per day. Time spent in each of the boxes was recorded for 15 min on day 3. Any rats that spent less than 180 seconds or more than 720 seconds in one of the conditioning chambers were eliminated from the study (<20%). The following day (day 4), all rats received a morning injection of the appropriate vehicle and were immediately placed in the appropriate pairing chamber for 30 min. Four hours later, all rats received drug administration and were immediately placed in the opposite chamber for 30 min. Testing, in which the animals were placed drug-free in the CPP boxes with access to all chambers, occurred the following day (20 hours following drug pairing).

Data Analysis

Within each treatment group, post-administration means were compared with the baseline values by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc analysis of least significant difference for multiple comparisons. A probability level of 0.05 was used to establish significance. For conditioned place pairing, the effects of injury and conditioning chamber were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bonferonni t-tests were used for post-hoc analysis of pre-conditioning (BL) vs post-conditioning values within each treatment group. Pairwise t-test was used to analyze the difference scores which were calculated as post-conditioning (test) – pre-conditioning (BL) time spent in the drug paired chamber.

Results

MIA-induced pain persists across 4 weeks

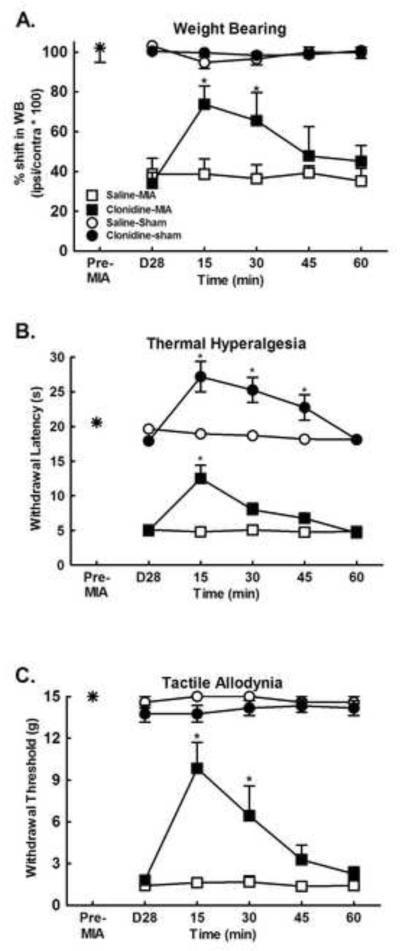

Intra-articular MIA injection produced significant shift in weight bearing that was apparent at 28 days post-injection (Fig. 1a, p<0.0001, compared with pre MIA baseline). Clonidine (10 μg)was given spinally at the 28 day post-MIA time-point in order to determine the features of MIA pain at this time-point.Spinal clonidine elicitedtime-dependent reversal of the MIA-induced shift in weight bearing with peak effect observed at 15 min post-administration (Fig 1a, *p<0.05 compared to post-MIA). In addition, MIA produced significant tactile allodynia in the ipsilateralhindpaw at the 28 day time-point (Fig 1b, p<0.0001 compared with pre-MIA baseline). Spinal clonidine reversed MIA-induced tactile allodynia, with peak effect at 15 min post-administration (Fig 1b, *p<0.05 compared to post-MIA). MIA further induced thermal hypersensitivity in the ipsilateralhindpaw at this time-point (Fig 1c, *p<0.05 compared with pre-MIA baseline). Spinal clonidine attenuated the MIA-induced thermal hyperalgesia with peak effect observed at 15 min post-administration. Spinal clonidine also induced thermal antinociception in the control animals that received intra-articular saline, with peak effect observed 15 min post-administration (Fig 1c, *p<0.05 compared to post-MIA).

Figure 1.

A) MIA induced a shift in weight bearing from the ipsilateralhindlimb was observed 28 days following MIA injection (Post-MIA). The MIA-induced shift was reversed by spinal administration of clonidine (10 μg). *indicates p<0.05 compared to post-MIA, n=8. B) MIA-induced reduction in paw withdrawal thresholds to calibrated von Frey filaments was observed 28 days post MIA injection indicating referred tactile allodynia (Post-MIA). Spinal clonidine (10 μg) reversed the MIA induced tactile allodynia. *indicates p<0.05 compared to post-MIA, n=8. C) MIA-induced reduction in paw withdrawal latency to noxious thermal stimulation was observed 28 days post MIA (Post-MIA). The MIA-induced referred thermal hyperalgesia was reversed by spinal administration of clonidine. Of note, spinal clonidine at this dose also induced thermal antinociception in the saline control animals. *indicates p<0.05 compared to Post-MIA, n=8.

MIA induces persistentongoingpain that is blocked by spinal clonidine

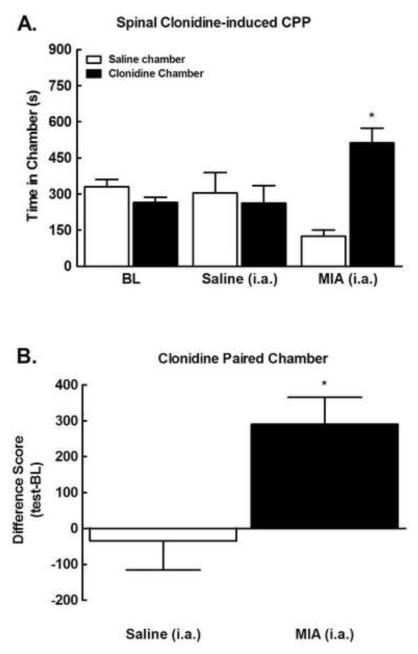

To determine whether MIA induces long-lasting ongoing pain, we determined whether spinal administration of clonidine (10 μg) induced conditioned place preference 28 days following MIA administration. Pre-conditioning time spent in the saline versus clonidine paired chambers did not differ between groups (p>0.05), therefore their data was pooled for graphical representation (Fig 2a). MIA treated rats showed conditioned place preference for the clonidine paired chamber as indicated by a significant increase in time-spent in the clonidine paired chamber (*p<0.05 compared to pre-conditioning BL). In contrast, clonidine failed to produce place preference in the control rats (sham) that received intra-articular saline injection. These data indicate that the spinal clonidine induced chamber preference only in animals with MIA, reflecting the presence ofMIA-induced ongoing pain. Comparison of difference scores (post-conditioning-preconditioning) for time spent in the clonidine paired chamber confirmed that only MIA rats increased time spent in the clonidine paired chamber (Fig 2b, *p<0.05).

Figure 2.

A) Spinal clonidine administered 28 days post MIA induced conditioned place preference in MIA treated rats. Spinal clonidine did not induce chamber preference in saline controls. *indicates p<0.05 compared to pre-conditioning time, n=7. B) Difference scores (test time-preconditioning time) confirm that MIA, but not saline control rats increased time spent in the clonidine paired chamber. *indicates p<0.05 compared to saline.

Discussion

The disease processes that leads to the structural changes and pain associated with OA are complex and poorly understood. Osteoarthritis is characterized by degeneration of articular cartilage, synovitis, remodeling of subchondral cortical and trabecular bone, and joint capsular tissues [12]. Cytokine profiles in osteoarthritis synovium support a role for inflammation and oxidative stress in the disease process [12]. MIA induces synovitis lasting through 3 days post injection which is followed by thinning of articular cartilage and subsequent lesion of subchondral bone at days 8-14 onwards [18]. Various studies have demonstrated that MIA induces pain behaviors similar to evoked and avoidance behaviors reported in OA patients including: shift in weight bearing, hyperalgesia, and referred pain measured as decreased paw withdrawal thresholds to stimuli applied to the ipsilateralhindpaw[5, 18, 21, 27]. However, whether ongoing pain, such as that experienced by OA patients at rest, is present in the MIA model has not beendemonstrated. Here, we show that administration of spinal clonidine, a drug known to produce relief of pain clinically, induces CPP selectively in MIA treated rats. Thus, thismanipulation only inducesplace preference in the presence of injury suggesting relief of an aversive state due to MIA.

In addition, our data indicates that evoked and ongoing pain are present at a time point significantly after MIA administration; both are observed 4 weeks (28 days) following MIA administration.The MIA-induced evoked pain behaviors observed at 28 days post MIA are consistent with other reports on MIA-induced pain [6, 21]. Here, we demonstrate that MIA also inducesongoing pain that is present at this time point.The observation of ongoing pain at this late time point post-MIA suggests the possibleinduction of long-term, ongoing damage to the knee joint that may actively drive primary afferent fibers. Other studies have demonstrated the development of evoked pain behaviors within 7 days post-MIA injection that persists across weeks [9, 18, 21]. Additionally, our study used a high dose of MIA to model severe OA.Whether MIA-induced ongoing pain has a similar time-course or would occur at lower MIA doses is currently unknown. Indeed, it is possible that ongoing pain shows delayed development as compared to evoked pain, as clinical observations indicate development of chronic ongoing pain at mid- to late- stage OA [16].In animal models of inflammatory joint disease and OA, it has been shown that joint primary afferent nerves become sensitized [23-25]. Sensitization of these peripheral nerves leads to enhanced mechanosensation in the affected joint, reflected as allodynia, hyperalgesia, and shift in weight bearing [5, 6, 17, 21, 23, 24, 27].It is possible that damage to nerves may drive ongoing pain though this has not been established. This possibility is in agreement with clinical reports that peripheral administration of lidocaine blocks pain in OA patients [2-4, 10, 11].Whether there is nerve damage that underlies ongoing pain is not known.

It has been noted that there are time-dependent changes in the structural pathology following injection of MIA into the knee, with inflammation observed at early time-points (e.g. 3 days post-administration), and diminished at later time-points (days 8-14 post-MIA) whereas ATF-3, a marker for nerve injury, is observed at these later time-points (days 8-14 post-MIA) [18]. Consistent with the time-dependent pathological changes, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. naproxen, celcoxib) show improved blockade of MIA-induced weight bearing asymmetry at early time-points following MIA injection (Day 3), compared to later time-points (Day 14 or later) [9, 18, 21]. In contrast, agents such as gabapentin and amitriptyline effectively blocked MIA-induced weight-bearing asymmetry at the later time-points (Day 14, 21, 28), suggesting a potential neuropathic pain component of MIA-induced pain at these time-points [18, 27]. We note that potential contribution of ectopic discharge to MIA induced pain cannot be discounted, as some signs of nerve injury have been demonstrated[18]. However, ongoing pain may also result from physiological function of uninjured nerves driven by mediators in the local mileau as well asenhanced activationof sensitized afferent fibers resulting from movement. The contribution of movement is also uncertain asprevious studies have not demonstrated changes in locomotor activity in MIA treated animals and the shift in weight bearing suggests a protective behavior that would diminish the influence of movement evoked pain.

Spinal administration of clonidine has been demonstrated to block neuropathic pain in humans [26] and blocks evoked and nerve-injury induced spontaneous pain in rats [20]. Spinal clonidine blocked MIA-induced evoked pain and induced CPP selectively in MIA treated rats. While spinal clonidine increased thermal thresholds in the sham operated rats, no effect was observed in in the place preference assay. The latter indicates that spinal clonidine does not induce reward in the absence of pain and highlights the differential activity of pharmacological treatments with specific endpoints. Critically, these findings suggest that the clonidine-induced CPP in the MIA treated rats is due to blockade of ongoing pain and suggests that the MIA model may be useful in capturing features of the severe ongoing pain experienced by OA patients with mid- or advanced stages of osteoarthritis [15, 16]. Such a model may be used to determine specific mediators of persistent OA pain as well as to provide pre-clinical analysis of novel compounds developed for long-term management of OA pain, including ongoing pain experienced in the absence of external stimulation, often described as pain at rest.

Research Highlights.

Intra-articular injection of MIA induces ongoing pain at 28 days following injection.

Intra-articular MIA induces shift in weight bearing and evoked pain at 28 days following injection.

Spinal clonidine blocks MIA-induced ongoing pain, shift in weight bearing, and evoked pain.

MIA-induces ongoing and evoked pain at 28 days allowing for mechanistic investigation.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Abramson S, Attur M. Developments in the scientific understanding of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009;11:227. doi: 10.1186/ar2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Argoff CE. Conclusions: chronic pain studies of lidocaine patch 5% using the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(Suppl 2):S29–31. doi: 10.1185/030079904X12979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Baliki MN, Geha PY, Jabakhanji R, Harden N, Schnitzer TJ, Apkarian AV. A preliminary fMRI study of analgesic treatment in chronic back pain and knee osteoarthritis. Mol Pain. 2008;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Burch F, Codding C, Patel N, Sheldon E. Lidocaine patch 5% improves pain, stiffness, and physical function in osteoarthritis pain patients. A prospective, multicenter, open-label effectiveness trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chandran P, Pai M, Blomme EA, Hsieh GC, Decker MW, Honore P. Pharmacological modulation of movement-evoked pain in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Combe R, Bramwell S, Field MJ. The monosodium iodoacetate model of osteoarthritis: a model of chronic nociceptive pain in rats? Neurosci Lett. 2004;370:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dieppe P, Brandt KD. What is important in treating osteoarthritis? Whom should we treat and how should we treat them? Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2003;29:687–716. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(03)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. The Lancet. 2005;365:965–973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fernihough J, Gentry C, Malcangio M, Fox A, Rediske J, Pellas T, Kidd B, Bevan S, Winter J. Pain related behaviour in two models of osteoarthritis in the rat knee. Pain. 2004;112:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Galer BS, Sheldon E, Patel N, Codding C, Burch F, Gammaitoni AR. Topical lidocaine patch 5% may target a novel underlying pain mechanism in osteoarthritis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1455–1458. doi: 10.1185/030079904X2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gammaitoni AR, Galer BS, Onawola R, Jensen MP, Argoff CE. Lidocaine patch 5% and its positive impact on pain qualities in osteoarthritis: results of a pilot 2-week, open-label study using the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(Suppl 2):S13–19. doi: 10.1185/030079904X12951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Articular cartilage and subchondral bone in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1192:230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE, Carr AJ, Chizh B, Chessell I, Tracey I. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Care & Research. 2009;61:1226–1234. doi: 10.1002/art.24837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hawker GA. Experiencing painful osteoarthritis: what have we learned from listening? Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2009;21:507–512. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832e99d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR, Cibere J, Jordan JM, March L, Suarez-Almazor M, Gooberman-Hill R. Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis - an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Honore P, Chandran P, Hernandez G, Gauvin DM, Mikusa JP, Zhong C, Joshi SK, Ghilardi JR, Sevcik MA, Fryer RM, Segreti JA, Banfor PN, Marsh K, Neelands T, Bayburt E, Daanen JF, Gomtsyan A, Lee CH, Kort ME, Reilly RM, Surowy CS, Kym PR, Mantyh PW, Sullivan JP, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR. Repeated dosing of ABT-102, a potent and selective TRPV1 antagonist, enhances TRPV1-mediated analgesic activity in rodents, but attenuates antagonist-induced hyperthermia. Pain. 2009;142:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ivanavicius SP, Ball AD, Heapy CG, Westwood FR, Murray F, Read SJ. Structural pathology in a rodent model of osteoarthritis is associated with neuropathic pain: increased expression of ATF-3 and pharmacological characterisation. Pain. 2007;128:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].King T, Rao S, Vanderah T, Chen Q, Vardanyan A, Porreca F. Differential blockade of nerve injury-induced shift in weight bearing and thermal and tactile hypersensitivity by milnacipran. J Pain. 2006;7:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].King T, Vera-Portocarrero L, Gutierrez T, Vanderah TW, Dussor G, Lai J, Fields HL, Porreca F. Unmasking the tonic-aversive state in neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nn.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pomonis JD, Boulet JM, Gottshall SL, Phillips S, Sellers R, Bunton T, Walker K. Development and pharmacological characterization of a rat model of osteoarthritis pain. Pain. 2005;114:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sarzi-Puttini P, Cimmino MA, Scarpa R, Caporali R, Parazzini F, Zaninelli A, Atzeni F, Canesi B. Osteoarthritis: An Overview of the Disease and Its Treatment Strategies. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schaible HG, Schmidt RF. Effects of an experimental arthritis on the sensory properties of fine articular afferent units. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:1109–1122. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schaible HG, Schmidt RF. Time course of mechanosensitivity changes in articular afferents during a developing experimental arthritis. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:2180–2195. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Schuelert N, McDougall JJ. Electrophysiological evidence that the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor antagonist VIP6-28 reduces nociception in an animal model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Uhle EI, Becker R, Gatscher S, Bertalanffy H. Continuous intrathecal clonidine administration for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2000;75:167–175. doi: 10.1159/000048402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vonsy JL, Ghandehari J, Dickenson AH. Differential analgesic effects of morphine and gabapentin on behavioural measures of pain and disability in a model of osteoarthritis pain in rats. Eur J Pain. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Analgesia mediated by a direct spinal action of narcotics. Science. 1976;192:1357–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1273597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]