Abstract

The expression of GABAA receptors and the efficacy of GABAergic neurotransmission are subject to adaptive compensatory regulation as a result of changes in neuronal activity. Here, we show that activation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) leads to Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) phosphorylation of S383 within the β3 subunit of the GABAA receptor. Consequently, this results in rapid insertion of GABAA receptors at the cell surface and enhanced tonic current. Furthermore, we demonstrate that acute changes in neuronal activity leads to the rapid modulation of cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors and tonic current, which are critically dependent on Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs and CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383. These data provide a mechanistic link between activity-dependent changes in Ca2+ influx through L-type channels and the rapid modulation of GABAA receptor cell surface numbers and tonic current, suggesting a homeostatic pathway involved in regulating neuronal intrinsic excitability in response to changes in activity.

Keywords: CaMKII, exocytosis, GABAA receptors, phosphorylation, tonic inhibition

Introduction

GABAA receptors are responsible for fast inhibitory neurotransmission in the brain, which consists of two components: phasic and tonic inhibition (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). These receptors are the major sites of action for both benzodiazepines and barbiturates, and are heteropentameric Cl− permeable, ligand-gated ion channels that are assembled from a range of homologous subunits that share a common structure (Rudolph and Mohler, 2004; Olsen and Sieghart, 2009). Insertion and internalization of GABAA receptors occur outside the synapse (Bogdanov et al, 2006) and receptors are exchanged between synaptic an extrasynaptic regions by lateral diffusion (Jacob et al, 2005; Thomas et al, 2005; Bogdanov et al, 2006), representing a mechanism whereby the efficacy of synaptic inhibition can be modulated (Thomas et al, 2005).

Phosphorylation of the intracellular domains between transmembrane domain (TM) 3–4 of the GABAA receptor β and γ subunits by serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases has been shown to alter receptor function either by a direct effect on receptor properties, such as the probability of channel opening or desensitization, or by regulating trafficking of the receptor to and from the cell surface (Moss and Smart, 2001; Jacob et al, 2008). CaMKII phosphorylation sites within GABAA receptor subunits were initially identified using glutathionie-S-transferase fusion proteins of the large intracellular loops of these receptor subunits (McDonald and Moss, 1994, 1997). In a recombinant system, expression of α1β3 GABAA receptor subunits in a neuronal cell line led to the identification of β3S383 as the major site for CaMKII phosphorylation and modulation of whole-cell GABA currents (Houston et al, 2007). In the hippocampus modulation of GABAA receptor function by CaMKII has been reported, whereby CaMKII activation potentiates inhibitory post-synaptic currents (IPSCs) and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (IPSPs) in CA1 pyramidal cells (Wang et al, 1995; Wei et al, 2004). In other neuronal preparations, CaMKII activation increased the amplitude of whole-cell currents and IPSCs recorded from neurons of the spinal cord dorsal horn (Wang et al, 1995), cortex (Aguayo et al, 1998) and cerebellum (Houston and Smart, 2006; Houston et al, 2008).

GABAA receptor activation regulates the excitability of neural circuits, and a number of studies in cultures of dissociated neurons have provided evidence that chronic changes (i.e., days) in neuronal activity can lead to homeostatic scaling of GABAergic synaptic strength (Kilman et al, 2002; Hartman et al, 2006; Swanwick et al, 2006; Saliba et al, 2007). Additionally, the intrinsic excitability of a neuron (i.e., voltage-dependent conductances) is also subject to homeostatic regulation (Nelson and Turrigiano, 2008). There is evidence now suggesting that the persistent GABA-mediated tonic current plays a role in regulating intrinsic neuronal excitability (Mody, 2005).

Here, we have begun to investigate the effects of L-type VGCC activation on the forward trafficking of GABAA receptors and tonic current. We find that Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs induces an increase in β3S383 phosphorylation by CaMKII, which promotes the rapid accumulation of α5/β3 containing GABAA receptors at the neuronal cell surface and enhances tonic current. Furthermore, CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 promotes the insertion of GABAA receptors into the neuronal membrane without influencing the endocytosis of these receptors. Lastly, our findings show that acute changes in neuronal activity lead to the modulation of GABAA receptor accumulation at the cell surface and tonic current and these effects are critically dependent on L-type VGCC activation and phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII.

Results

Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs increases the cell surface expression of GABAA receptors and tonic current

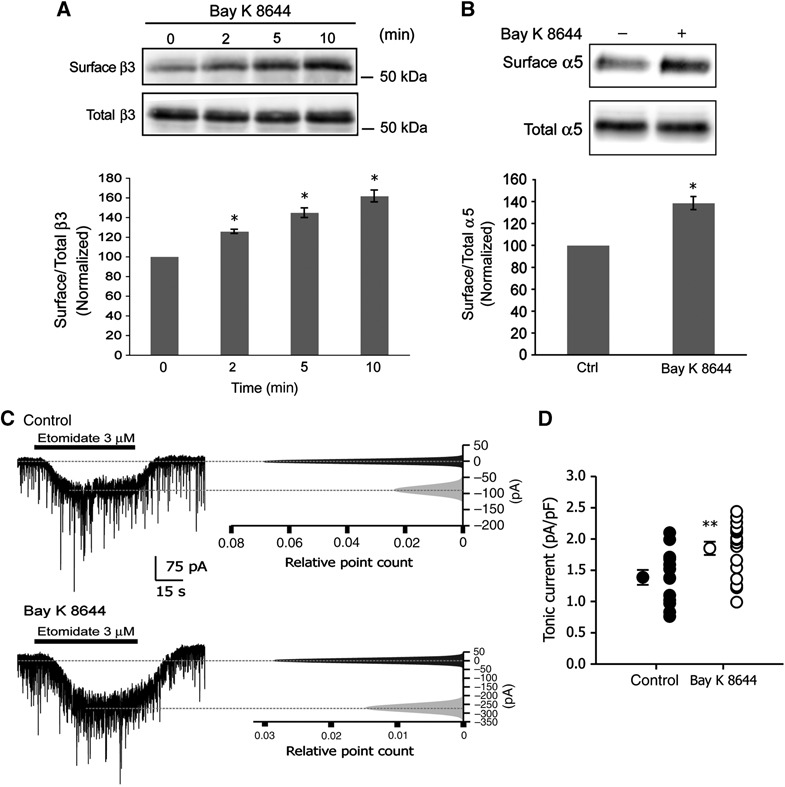

We have previously shown that chronic blockade of L-type VGCCs in cultured hippocampal neurons reduces the expression of GABAA receptors and the efficacy of GABAergic neurotransmission (Saliba et al, 2009). As our studies centre on GABAA receptors in the hippocampus, our experiments will largely focus on the β3 subunit as this is highly abundant in this brain region (Sperk et al, 1997). To determine if acute activation of L-type VGCCs has an effect on the cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors, we treated mature hippocampal neurons in culture, 16–21 days in vitro (div), with the dihydropyridine Bay K 8644, which is a voltage-dependent agonist that stabilizes the open state of L-type VGCCs (Bechem and Hoffmann, 1993). Neurons were incubated with Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for times ranging from 0 to 10 min and cell surface GABAA receptors were isolated by using a biotinylation assay (Figure 1A). Within 2 min of L-type channel activation, cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors containing β3 subunits increased by 25.6±2.2% (Figure 1A). L-type channel activation for 5 and 10 min resulted in a further increase in cell surface GABAA receptor expression of 44.6±4.9% and 61.0±6.0%, respectively (Figure 1A). We observed no change in the total expression level of GABAA receptors at these time points (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs increases cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors and the efficacy of tonic current. (A) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with Bay K 8644 for 0–10 min. Immunoblots show cell surface (biotinylated) and total levels of GABAA receptor β3 subunits as indicated. Graph shows the quantification of surface β3/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to values at time 0 (data are plotted as mean±s.e. *P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (B) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with Bay K 8644 for 10 min and cell surface proteins were isolated and immunoblotted with anti-α5 IgGs. Graph shows the quantification of cell surface α5/total α5 band intensity ratio normalized to control (ctrl) values (*P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (C) Left panels show whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings before (top) and after (bottom) application of Bay K 8644. Right panels show corresponding all point histograms of 10-s traces before ( ) and after (

) and after ( ) etomidate application. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. After subtracting baseline from current evoked by etomidate, tonic current was normalized to cell size. (D) Data plotted are values from individual neurons and their mean values±s.e. (control: n=13 and Bay K 8644: n=14; 3 different cultures; **P<0.01; t-test).

) etomidate application. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. After subtracting baseline from current evoked by etomidate, tonic current was normalized to cell size. (D) Data plotted are values from individual neurons and their mean values±s.e. (control: n=13 and Bay K 8644: n=14; 3 different cultures; **P<0.01; t-test).

GABAA receptor α5 subunits are abundantly expressed in the CA1 and CA3 region of the hippocampus (Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Sperk et al, 1997; Sur et al, 1998) are predominantly extrasynaptic (Fritschy et al, 1998) and are responsible for tonic current in pyramidal cells (Caraiscos et al, 2004). As the GABAA receptor α5 subunit mainly assembles with the β3 subunit in hippocampal neurons (Sur et al, 1998), we speculated that α5 surface expression may also increase following Ca2+ influx through L-type channels. To test this prediction, we incubated hippocampal neurons with Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 5 min and isolated surface receptors using a biotinylation assay, observing an increase in surface α5 subunits of 38.6±5.9% (Figure 1B).

We considered the possible consequences of Ca2+-dependent upregulation of cell surface GABAA receptor α5/β3 subunit expression on the efficacy of tonic current and took recordings from cultured hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) following a 10-min application of 5 μM Bay K 8644 (Figure 1C). We applied etomidate to hippocampal neurons in culture to study the effects of Bay K 8644 on tonic conductance. Etomidate is a positive allosteric modulator selective for GABAA receptors containing β2 or β3 subunits and preferentially enhances tonic current generated by GABAA receptors containing the α5 subunit in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Caraiscos et al, 2004; Cheng et al, 2006). We observed an increase in tonic current, measured as the whole-cell current evoked by bath application of 3 μM etomidate (Figure 1C). Tonic current evoked by etomidate increased by 33.1% from 1.39±0.12 pA/pF in control neurons to 1.85±0.11 pA/pF following a 10-min application of Bay K 8644 (Figure 1D). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs leads to the rapid accumulation of GABAA receptors assembled from α5/β3 subunits at the cell surface and enhanced tonic current.

Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs increases phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII

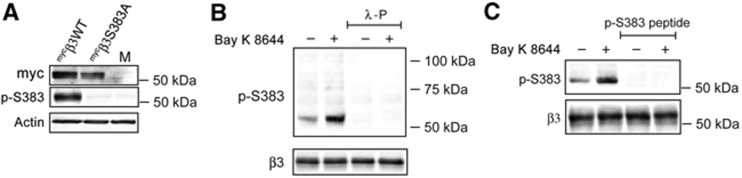

Previous studies have shown that CaMKII phosphorylates a GST fusion protein of the GABAA receptor β3 subunit at S383 (McDonald and Moss, 1997) and phosphorylates the same residue in recombinant GABAA receptor β3 subunits (Houston et al, 2007). To assess changes in phosphorylation following Ca2+ influx through L-type channels, we developed a rabbit phosphorylation site-specific antibody to phosphorylated β3S383 using the phospho-peptide CQYRKQSpMPKEG corresponding to the sequence surrounding β3S383. We discovered, using immunoblotting with anti-p-β3S383 IgGs, that under basal conditions myc-tagged β3WT is phosphorylated in a recombinant system using the neuronal cell line SH-SY5Y (Figure 2A) and also in cultures of dissociated hippocampal neurons, were a band of ∼55 kDa was detected (Figure 2B). Expression of myc-tagged phospho-null βS383A in SH-SY5Ys abolished the p-S383 immunosignal (Figure 2A). We increased Ca2+ influx into hippocampal neurons using Bay K 8644 (5 μM for 5 min) and observed and increase inthe p-S383 signal (Figure 2B and C). Also pretreatment of immunoblots with λ-phosphatase to remove phosphate groups, abolished the signal generated with anti-p-S383 IgGs (Figure 2B). In addition, preincubation of anti-p-S383 IgGs with a 500 molar excess of immunizing antigen prior to immunoblotting abolished the p-S383 immunosignal (Figure 2B). Collectively, these data show that anti-p-S383 IgGs are specific for phosphorylated β3S383.

Figure 2.

Specificity of anti-phosphorylated β3S383 IgGs. (A) SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were nucleofected with myc-tagged β3WT, myc-tagged β3S383A or mock nucleofected (M). Equal amounts of total protein were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-phosphorylated β3S383 (p-S383) IgGs, anti-myc IgGs and anti-actin IgGs, as indicated. (B) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with or without Bay K 8644 as indicated and immunoblots show p-S383 and total β3. Replicate blots were treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-P), prior to immunoblotting with anti-p-S383 IgGs as shown. (C) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with or without Bay K 8644. Immunoblots show p-S383 and total β3. Replicate bots were also immunoblotted with anti-p-S383 IgGs, which had been preabsorbed with an excess of p-S383 immunizing peptide, as indicated.

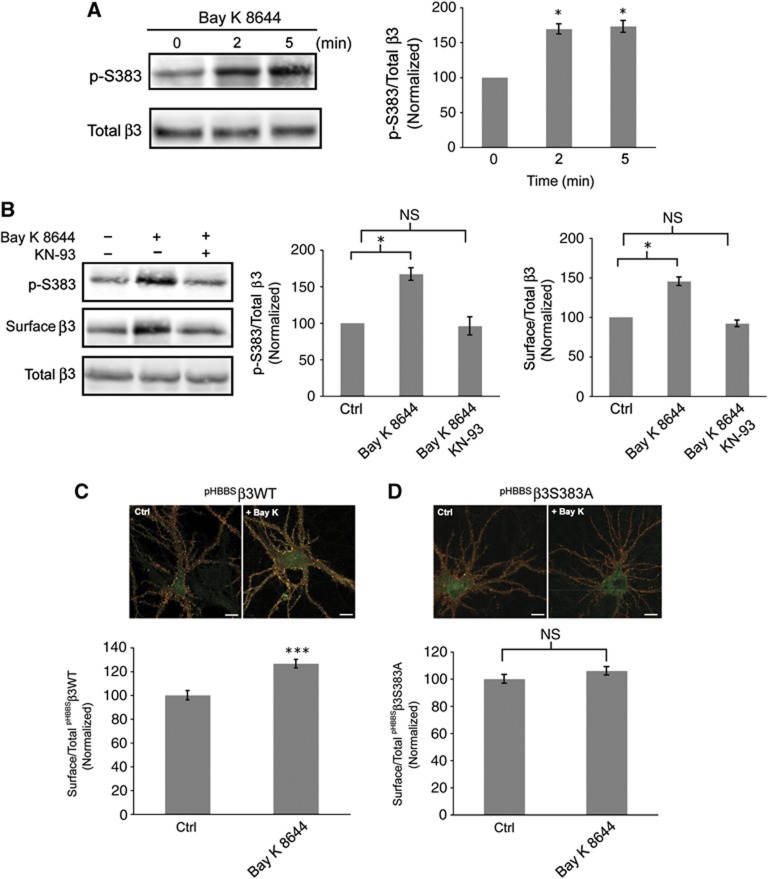

To determine whether the Ca2+-dependent increase in cell surface levels of GABAA receptors is associated with an increase in phosphorylation of β3S383, we activated L-type channels with Bay K 8644 (5 μM). Within 2 min following activation of L-type channels an increase in β3S383 phosphorylation of 69.3±7.2% was observed which remained stable at 5 min (Figure 3A). To demonstrate the role of CaMKII activity, neurons were incubated with the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 (4 μM) for 1 min prior to addition of Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 5 min (Figure 3B). Inhibiting CaMKII activity blocked the Ca2+-dependent rise in phosphorylation of β3S383 (Bay K 8644: 67.0±8.6% increase relative to control; Bay K 8644 plus KN-93: 4.0±12.4% decrease relative to control; Figure 3B) and the rise in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors (Bay K 8644: 45.3±5.3% increase relative to control; Bay K 8644 plus KN-93: 8.0±4.16% decrease relative to control; Figure 3B). In contrast, activation of extrasynaptic and synaptic NMDA receptors by brief application of NMDA to cultures of mature hippocampal neurons results in significant dephosphorylation of β3S383 by calcineurin (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 3.

CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 is essential for the Ca2+-dependent increase in GABAA receptor surface expression. (A) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with Bay K 8644 and immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. Graph represents the ratio of p-S383 to total β3 band intensities, normalized to values at time 0 (data are plotted as mean±s.e. *P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (B) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with or without Bay K 8644 plus KN-93 as indicated. Immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. First graph represents the ratio of p-S383 to total β3 band intensities, normalized to control (Ctrl) values and the second graph represents cell surface β3 to total β3 band intensity ratio, normalized to control (Ctrl) values (*P<0.05, n=3, NS: not significantly different, t-test. (C, D) Nucleofected neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT (C) and pHBBSβ3S383A (D) were incubated with Bay K 8644. Cell surface pHluorin-tagged β3 subunits are labelled red and the pHluorin signal (green) represents total pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A expression (scale bar 10 μm). Graphs represent cell surface/total ratios of pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A fluorescence intensity normalized to control (Ctrl) values (***P<0.001; NS: not significantly different; n>20 neurons, three independent cultures; t-test).

To assess whether β3S383 phosphorylation is critical for the observed Ca2+-dependent increase in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors, hippocampal neurons were nucleofected with β3WT and the phospho-null mutant β3S383A. Both β3WT and β3S383A are tagged at their N-termini with pHluorin (pH) and the α-bungarotoxin binding site—BBS (Bogdanov et al, 2006; Saliba et al, 2007; Jacob et al, 2009). Nucleofected neurons (14 div) were incubated with Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 10 min. To assess changes in the cell surface expression of pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A, fixed, non-permeabilized neurons were immunolabelled with anti-GFP IgGs (Figure 3C and D). Confocal images were taken of immunolabelled pyramidal cells and cell surface immunofluorescence intensity along 2–3 proximal dendrites was measured using the program Metamorph (Saliba et al, 2007). Activation of L-type channels increased pHBBSβ3WT surface expression by 25.0±3.5% (Figure 3C) but had no significant effect on pHBBSβ3S383A surface expression (6.0±3.1% increase relative to control; Figure 3D). Taken together, these data reveal that phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII is critical for the observed Ca2+-dependent rise in cell surface GABAA receptor numbers.

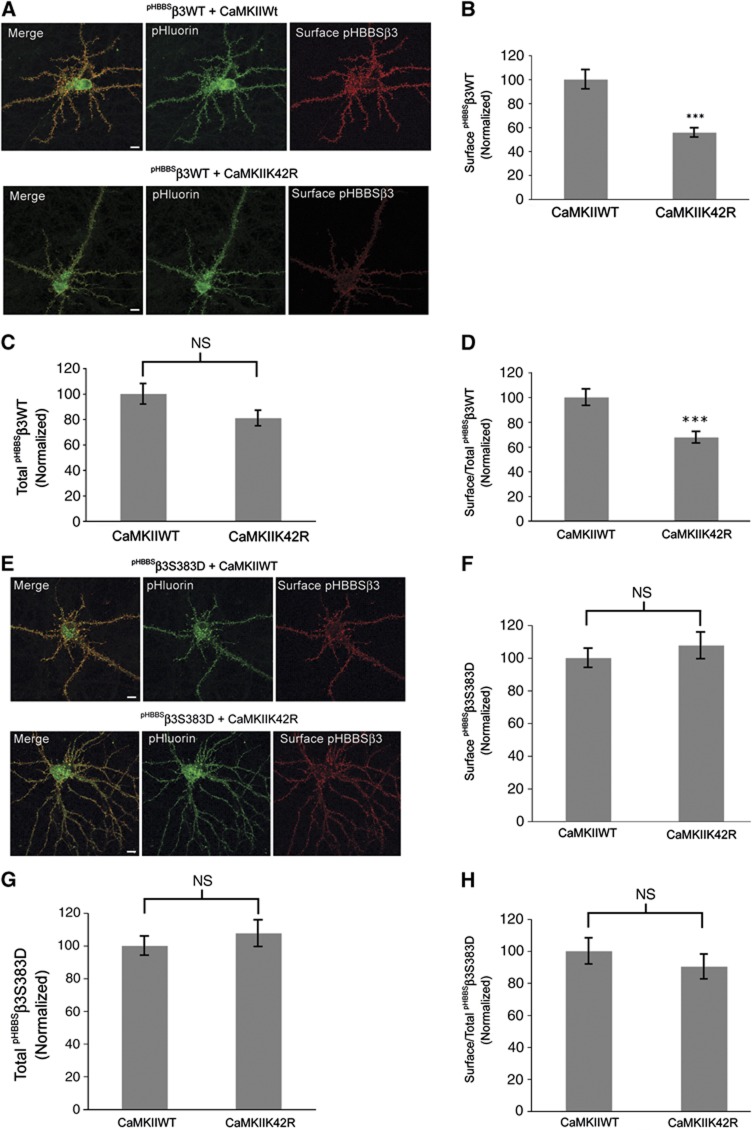

As an alternative to pharmacological blockade of CaMKII activity in assessing the role of phosphorylation of β3S383 in GABAA receptor accumulation at the cell surface, we used the CaMKII inactive mutant; CaMKIIK42R in our next set of experiments. Hippocampal neurons (15 div) were transfected with pHBBSβ3WT and CaMKIIWT and inactive CaMKIIK42R using Lipofectamine 2000. Neurons were transfected using double the amount of CaMKIIWT and CaMKIIK42R plasmid DNA compared with pHBBSβ3WT plasmid DNA and surface expression was assayed 24 h later (Figure 4A). Using immunofluorescence labelling of non-permeabilized neurons with anti-GFP IgGs, we observed that co-expression of inactive CaMKIIK42R with pHBBSβ3WT resulted in a reduction in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors by 44.0±3.0% (Figure 4B) compared with controls (pHBBSβ3WT and CaMKII WT) and a small non-significant reduction in total pHBBSβ3WT of 19.0±6.0% (Figure 4C). Additionally, we also observed a reduction in the ratio of cell surface to total pHBBSβ3WT of 32.3±4.6% in neurons expressing inactive CaMKIIK42R (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Expression of inactive CaMKIIK42R reduces GABAA receptor cell surface numbers. (A) Hippocampal neurons (15 div) were transfected with pHBBSβ3WT and CaMKIIWT and inactive CaMKIIK42R as indicated. Cell surface population of pHBBSβ3WT subunits is labelled red. The pHluorin (green) signal represents total pHBBSβ3WT expression (scale bar 10 μm). (B) Graph represents cell surface immunofluorescence intensity of pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIWT) values (data are plotted as mean±s.e., ***P<0.001; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures, t-test). (C) Graph represents total pHluorin fluorescence intensity of pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIWT) values (NS: not significantly different, n>20 neurons; three independent cultures, t-test). (D) Graph represents the cell surface/total fluorescence intensity ratio of pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3WT+CaMKIIWT) values (***P<0.001; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test). (E) Hippocampal neurons (15 div) were transfected with pHBBSβ3S383D and CaMKIIWT and inactive CaMKIIK42R as indicated. Cell surface population of pHBBSWTβ3S383D subunits is labelled red. The pHluorin (green) signal represents total pHBBSβ3S383D expression (scale bar 10 μm). (F) Graph represents cell surface immunofluorescence intensity of pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIWT) values (NS: not significantly different; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test). (G) Graph represents total pHluorin fluorescence intensity of pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIWT) values (NS: not significantly different; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test). (H) Graph represents the cell surface/total fluorescence intensity ratio of pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIK42R normalized to control (pHBBSβ3S383D+CaMKIIWT) values (NS: not significantly different, n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test.

To determine if the effect of inactive CaMKIIK42R on GABAA receptor cell surface expression is specific to β3S383, we co-transfected hippocampal neurons (15 div) with the phospho-mimic pHBBSβ3S383D subunit and CaMKIIWT and inactive CaMKIIK42R (Figure 4E). We observed no significant difference in the surface or total expression levels of pHBBSβ3S383D following co-expression with CaMKIIK42R compared with expression with control CaMKIIWT (surface β3S383D+CaMKIIK42R: 7.6±8.1% increase relative to CaMKIIWT; total β3S383D+CaMKIIK42R: 11.5±9.9% increase relative to CaMKIIWT; surface/total β3S383D ratio+CaMKIIK42R: 9.7±7.7% decrease relative to CaMKIIWT; Figure 4F–H). These experiments indicate that CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of GABAA receptor accumulation at the neuronal cell surface and further show that the effect of inactive CaMKII on GABAA receptor surface expression is specific to β3S383.

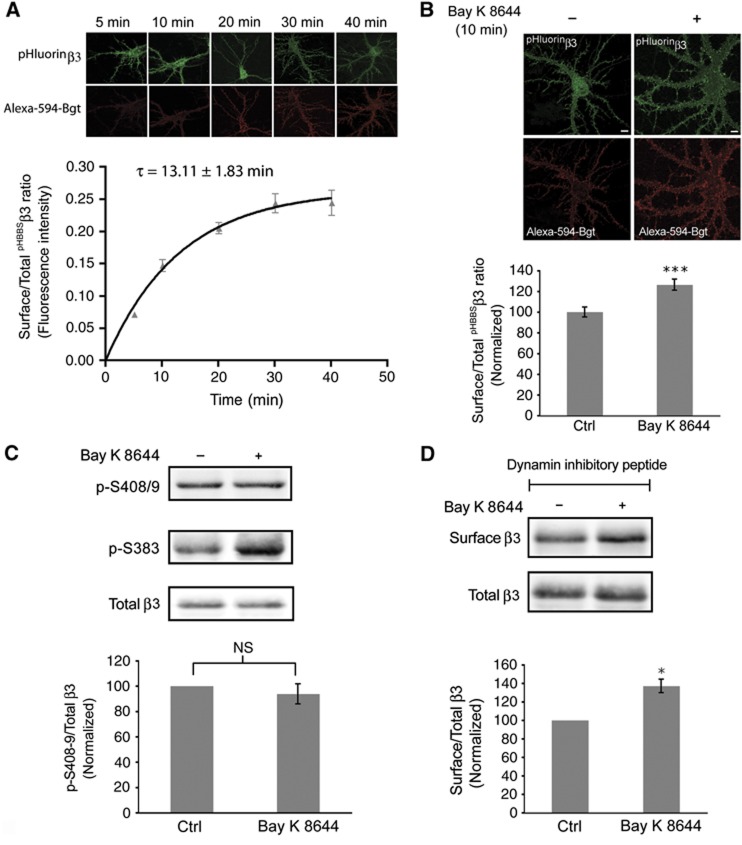

Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs increases the exocytosis of GABAA receptors

The Ca2+-dependent increase in GABAA receptor numbers at the cell surface could possibly result from a change in the insertion rate of receptors or result from an altered rate of endocytosis (Kittler et al, 2000, 2004; Jacob et al, 2009). To examine the contribution of insertion to the Ca2+-dependent rise in GABAA receptor cell surface numbers, we used nucleofected neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT and assessed insertion of receptors using Alexa-594 labelled α-bungarotoxin (Bgt), as previously described (Saliba et al, 2007, 2009). Briefly, hippocampal neurons (15 div) were incubated with unlabelled α-Bgt at 15°C to block existing cell surface pHBBSβ3WT subunits. Neurons were then incubated at 37°C with Alexa-594-Bgt for a range of time points between 0 and 40 min (Figure 5A). Cell surface levels of pHBBSβ3WT containing GABAA receptors increased gradually over time and the rate of receptor insertion was best described by a single exponential process with a time constant of 13.1±1.8 min (Figure 5A). To determine if Ca2+ influx through L-type channels increases the number of GABAA receptors being inserted, we incubated hippocampal neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT with or without Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 10 min in the presence of Alexa-594-Bgt. We assessed the level of insertion at 10 min by determining the fluorescence intensity of newly inserted pHBBSβ3WT (alexa-594-Bgt). The data were expressed as the ratio of newly inserted to total pHBBSβ3WT pHluorin fluorescence in control and Bay K 8644-treated neurons (Figure 5B). Compared with control levels, we observed a 26.4±5.3% increase in insertion of pHBBSβ3WT containing GABAA receptors following L-type channel activation for 10 min (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Activation of L-type VGCCs increases insertion of GABAA receptors. (A) Insertion of pHBBSβ3WT containing GABAA receptors over time. Newly inserted pHBBSβ3WT is labelled red (Aexa-594-Bgt). Graph represents the ratio of newly inserted pHBBSβ3 to total pHluorin fluorescence intensity over time. (B) Nucleofected hippocampal neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT were incubated with Alexa-594-Bgt with or without Bay K 8644 (scale bar 10 μm). Graph shows quantification of newly inserted pHBBSβ3WT with Bay K 8644 expressed as the surface/total pHBBSβ3WT fluorescence intensity ratio normalized to control (Ctrl) values (data are plotted as mean±s.e. ***P<0.001; n>20; three independent cultures; t-test). (C) Hippocampal neurons were treated with Bay K 8644. Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phosphorylated β3S408/9 IgGs (p-S408/9) and anti-p-S383 IgGs. Graph represents quantification of the ratio of band intensities of P-S408/9 to total β3 normalized to control (Ctrl) values (NS: not significantly different; n=4; t-test). (D) Hippocampal neurons were treated with myristoylated dynamin inhibitory peptide prior to incubation with or without Bay K 8644. Immunoblots show total and cell surface levels of β3 subunits as indicated. Graph represents quantification of the ratio of band intensities of cell surface and total β3 subunits, normalized to control (Ctrl) values (*P<0.05, n=3, t-test).

GABAA receptors are subject to constitutive endocytosis, which is mediated by the direct binding of clathrin adaptor protein AP2 to specific endocytosis motifs within the intracellular domains of GABAA receptor β1–β3 and γ2 subunits(Kittler et al, 2000, 2005; Jacob et al, 2009; Vithlani and Moss, 2009). Phosphorylation of S408 and S409 within the GABAA receptor β3 subunit (PKC and PKA phosphorylation sites) can modulate the binding of adaptins to GABAA receptors and thus modulate their rate of endocytosis (Kittler et al, 2005; Jacob et al, 2009; Vithlani and Moss, 2009). To determine if phosphorylation of β3S408/9 changes following activation of L-type channels we incubated hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) with Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 5 min and assessed phosphorylation of β3S408/9 using western blotting with anti-phosphorylated β3S408/9-specific IgGs (Jovanovic et al, 2004). We found no significant change in the phosphorylation of β3S408/9 following L-type channel activation (Bay K 8644: 6.2±4.5% decrease relative to control; Figure 5C) but observed an increase in β3S383 phosphorylation similar to the data in Figure 3A.

To further support our data that demonstrates Ca2+ influx through L-type channels regulates exocytosis of GABAA receptors, we used myristoylated dynamin inhibitory peptide, to block clathrin-dependent endocytosis, as used in previous studies (Kittler et al, 2000; Bogdanov et al, 2006; Jacob et al, 2009). Both control neurons and neurons exposed to Bay K 8644 were incubated with 50 μM myristoylated dynamin inhibitory peptide for 10 min prior to activation of L-type channels with Bay K 8644 (5 μM) for 5 min. Cell surface GABAA receptors were isolated using a biotinylation assay and we observed that blocking endocytosis did not prevent the Ca2+-dependent rise in surface GABAA receptor expression (Bay K 8644: 37.0±7.2% increase relative to control; Figure 5D). Together, these observations suggest that Ca2+ influx through L-type channels promotes the insertion of GABAA receptors without influencing receptor endocytosis.

The effects of phospho-null β3S383A and phospho-mimic β3S383D on GABAA receptor expression and tonic current

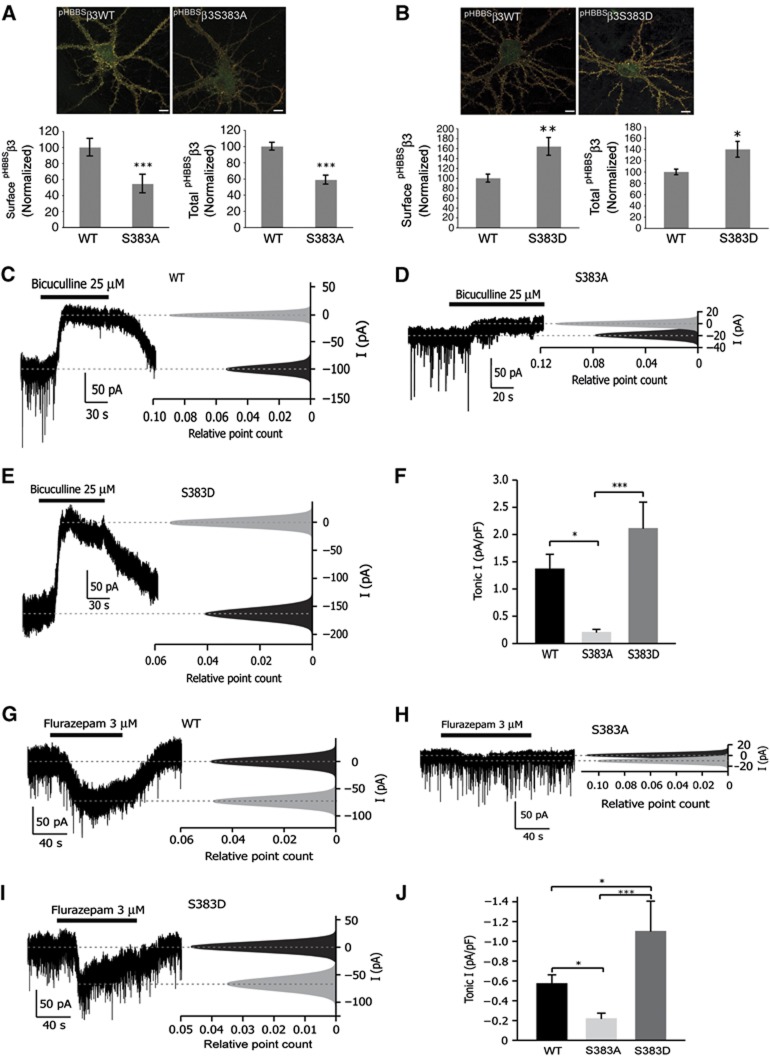

We used the phospho-null (pHBBSβ3S383A) and a phospho-mimic (pHBBSβ3S383D) mutant to further assess the role of phosphorylation of β3S383 in cell surface expression of GABAA receptors. In these experiments, we nucleofected hippocampal neurons with pHBBSβ3WT, pHBBSβ3S383A and pHBBSβ3S383D and determined cell surface and total expression levels at 15 div (Figure 6A and B). We observed a decrease in expression of surface (45.5±11.6%) and total (41.3±5.6%) pHBBSβ3S383A compared with pHBBSβ3WT expression levels (Figure 6A). In contrast, the surface and total expression levels of pHBBSβ3S383D were markedly above those of pHBBSβ3WT levels by 43.8±15.0% and 53.0±16.3%, respectively (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

The effects of phospho-null β3S383A and phospho-mimic β3S383D on GABAA receptor expression and tonic current. (A) Cell surface pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A subunits were labelled red and the pHluorin signal (green) represents total pHBBSβ3 expression (scale bar 10 μm). Graphs represent cell surface and total fluorescence intensity normalized to control (pHBBSβ3WT) values as indicated (***P<0.001; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test). (B) Comparison of pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383D surface and total expression. Cell surface receptors were labelled as in (A) (scale bar 10 μm). Graphs represent cell surface and total fluorescence intensity normalized to control (pHBBSβ3WT) values as indicated (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; n>20 neurons; three independent cultures; t-test). (C–E) Representative traces with corresponding all-point histograms from hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) nucleofected with pHBBSβ3WT (C), pHBBSβ3S383A (D) and pHBBSβ3S383D (E) constructs. Tonic current was expressed as the difference in baseline current before and after application of bicuculline (25 μM). The 10-s fragments of recordings before and during bicuculline application were taken and all-point histograms plotted. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. (F) Summary of recordings obtained from 8 (pHBBSβ3WT), 8 (pHBBSβ3S383A) and 5 (pHBBSβ3S383D) hippocampal neurons from three independent cultures. Tonic current was normalized to the cell size. (*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.) (G–I) Representative traces with corresponding all-point histograms from hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) nucleofected with pHBBSβ3WT (G), pHBBSβ3S383A (H) and pHBBSβ3S383D (I) constructs. Tonic current was expressed as the difference in baseline current before and after application of flurazepam (3 μM). The 10-s fragments of recordings before and during flurazepam application were taken and all-point histograms plotted. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. (J) Summary of recordings obtained from 8 (pHBBSβ3WT), 8 (pHBBSβ3S383A) and 3 (pHBBSβ3S383D) hippocampal neurons from three independent cultures. Tonic current was normalized to the cell size. (*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001; one-way ANOVA with Newman–Keul post-hoc test.)

We further assessed changes in surface expression of β3S383 phospho-mutants by measuring tonic current, using whole-cell patch clamp recordings. Bath application of bicuculline (25 μM) dramatically decreased whole-cell holding current in hippocampal neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383D (Figure 6C and E), but only had a minor effect in pHBBSβ3S383A-expressing neurons (Figure 6D). Whole-cell current change, measured as a difference between baseline before and after bicuculline application was 1.36±0.27 pA/pF for pHBBSβ3WT, 2.11±0.75 pA/pF for pHBBSβ3S383D and 0.20±0.06 pA/pF for pHBBSβ3S383A, respectively (Figure 6F). In agreement with higher surface expression of pHBBSβ3S383D containing GABAA receptors, the benzodiazepine flurazepam (3 μM) greatly potentiated the holding current in neurons expressing β3S383D when compared with neurons expressing the pHBBSβ3WT subunit (−0.57±0.09 pA/pF for pHBBSβ3WT; −1.10±0.31 pA/pF, for pHBBSβ3S383D; Figure 6G, I and J). In neurons expressing the phospho-null pHBBSβ3S383A subunit, flurazepam showed a lower potentiation of holding current compared with neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT (−0.57±0.09 pA/pF, for pHBBSβ3WT; −0.22±0.06 pA/pF, for pHBBSβ3S383A; Figure 6G, H and J). These data indicate that pHBBSβ3 subunits assemble into functional GABAA receptors containing γ subunits. Furthermore, these results also show that expression of β3S383A and β3S383D have opposite effects on GABAA receptor expression and tonic current.

Stimulating neuronal activity increases phosphorylation of β3S383, cell surface expression of GABAA receptors and tonic current

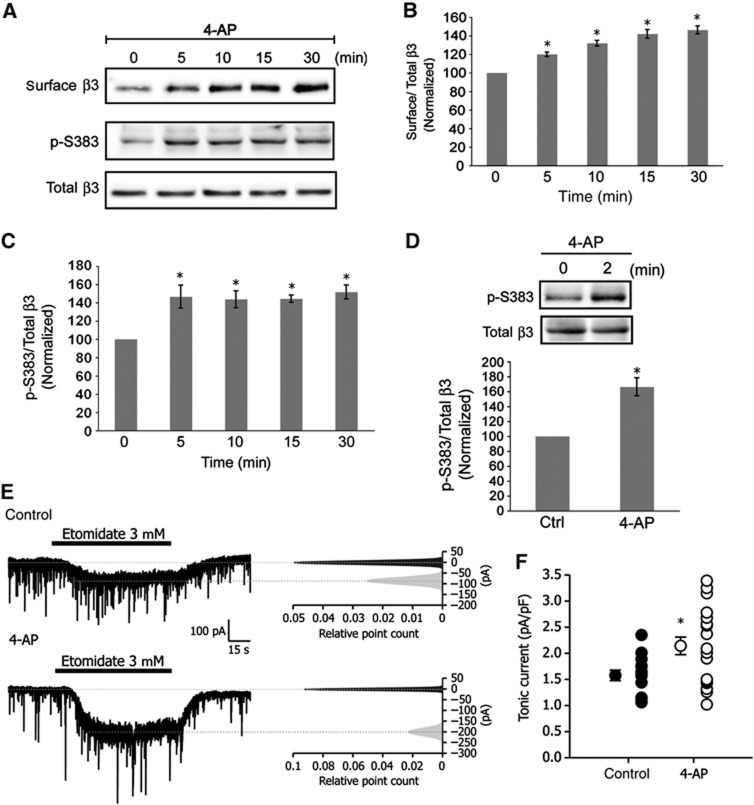

A prolonged increase (24 h) in neuronal activity in cultured neurons has been previously shown to upregulate the expression of GABAA receptors (Saliba et al, 2007). Thus, the question arises whether an acute increase in neuronal activity lasting minutes, as opposed to several hours, has an influence on the expression of cell surface GABAA receptors. To explore this possibility, we incubated hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) with the weak K+ channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 50 μM) for time points ranging from 0 to 30 min (Figure 7A). Cell surface GABAA receptors were isolated using a biotinylation assay and surface GABAA receptors were found to rise gradually over time in the presence of 4-AP with a 20.0±2.5% increase in receptor numbers at 5 min. By 30 min GABAA receptor cell surface expression levels had increased by 46.3±4.2% compared with levels at time 0 (Figure 7A and B). Given an acute increase in neuronal activity promotes the accumulation of new GABAA receptors at the cell surface, we speculated that phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII might mediate the effects of neuronal activity on the rise in cell surface receptor numbers. To assess the role of β3S383 phosphorylation in activity-dependent changes in cell surface GABAA receptor numbers, we incubated hippocampal neurons for 0 to 30 min with 4-AP (50 μM) and determined any changes in phosphorylation (Figure 7A). A rapid increase in phosphorylation was observed (51.0±5.6%) following a 5-min incubation with 4-AP which remained stable throughout the 30-min stimulation (Figure 7A and C). To determine if activity-dependent phosphorylation of β3S383 that we had observed in cultured hippocampal neurons occurs in the intact hippocampus, we incubated acute hippocampal slices with 50 μM 4-AP for 2 min. We assayed the level of β3S383 phosphorylation in lysates and observed a 67±12.5% rise in β3S383 phosphorylation (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Enhancing neuronal activity increases phosphorylation of β3S383, the number of cell surface GABAA receptors and tonic current. (A) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with 4-AP for times indicated. Immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. (B) Graph shows the quantification of cell surface β3/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to values at time 0 (data are plotted as mean±s.e. *P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (C) Graph shows the quantification of the ratio of p-S383 to total β3 band intensities, normalized to values at time 0 (*P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (D) Acute hippocampal slices incubated with 4-AP. Immunoblots show p-S383 and total β3. Graph shows the quantification of the ratio of p-S383 to total β3 band intensities, normalized to values at time 0 (*P<0.05, n=3, t-test). (E) Control whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings before (top) and after (bottom) application of 4-AP. Right panels: corresponding all-point histograms of 10-s traces before ( ) and after (

) and after ( ) etomidate application. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. After subtracting baseline from current evoked by etomidate, tonic current was normalized to cell size. (F) Data plotted are values from individual neurons and their mean values±s.e. (control, n=14, 4-AP, n=19, four independent cultures; *P<0.05; t-test).

) etomidate application. Histograms were fitted with single Gaussian functions, and means were determined. After subtracting baseline from current evoked by etomidate, tonic current was normalized to cell size. (F) Data plotted are values from individual neurons and their mean values±s.e. (control, n=14, 4-AP, n=19, four independent cultures; *P<0.05; t-test).

In parallel to an increase in GABAA receptor surface expression, an acute increase in neuronal activity also augmented tonic current. Following the incubation of cultured hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) with 100 μM 4-AP (30 min), the whole-cell current evoked by bath application of etomidate (3 μM) increased by 37.2% from 1.56±0.10 pA/pF in control neurons to 2.14±0.17 pA/pF following application of 4-AP (Figure 7E and F). Collectively, these experiments show that acutely stimulating neuronal activity promotes the phosphorylation of β3S383 leading to an increase in GABAA receptor surface expression and an increase in tonic current.

Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs mediates activity-dependent CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 and increases GABAA receptor surface expression

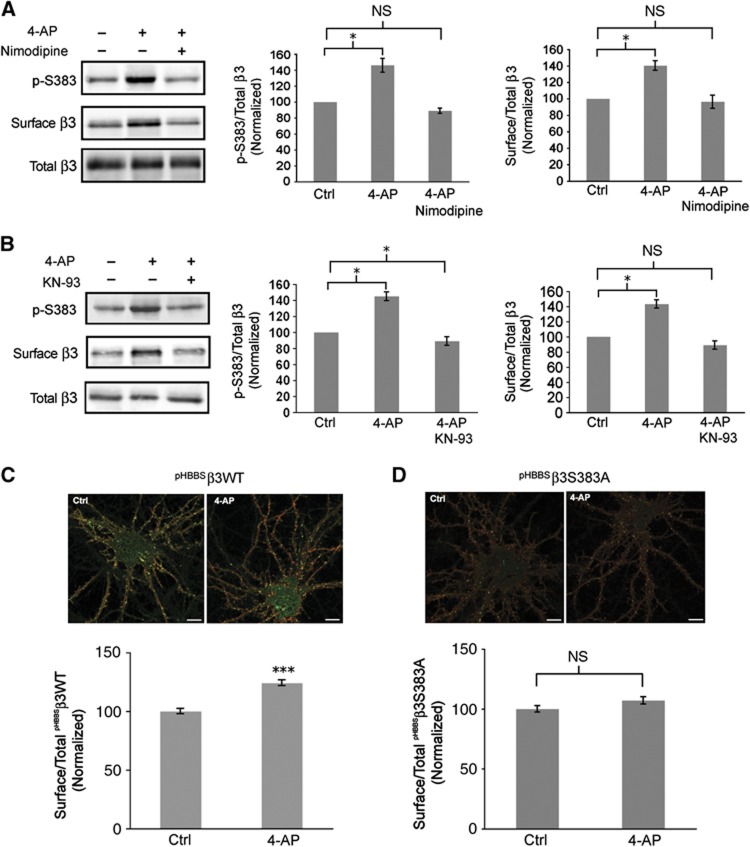

Stimulating neuronal activity results in an increase in Ca2+ influx via a number of different VGCCs. Given that L-type channel activation induces phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII, we assessed the role of L-type VGCC channel activation in modulating activity-dependent phosphorylation of β3S383 and cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors. Hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) were incubated with or without 4-AP (50 μM) plus the L-type channel blocker nimodipine (10 μM) for 30 min (Figure 8A). Blocking L-type channels with nimodipine prevented the activity-dependent increase in β3S383 phosphorylation (4-AP: 45.0±8.6% increase relative to control; 4-AP plus nimodipine: 6.4±3.2% decrease relative to control; Figure 8A) and the increase in cell surface levels of GABAA receptors (4-AP: 40.33±5.9% increase relative to control; 4-AP plus nimodipine: 3.7±8.0% decrease relative to control; Figure 8A). These experiments underscore the critical importance of Ca2+ influx through L-type channels in mediating the activity-dependent increase in GABAA receptor cell surface expression.

Figure 8.

Activation of L-type VGCCs and CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 are essential for the activity-dependent increase in surface GABAA receptor expression. (A) Hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) were incubated with or without 4-AP plus nimodipine. Immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. First graph represents p-S383/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to control (Ctrl) values (data are plotted as mean±s.e. *P<0.05, NS; not significantly different, n=3, t-test). Second graph represents surface β3/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to control (Ctrl) values (*P<0.05%, NS: not significantly different, n=3, t-test). (B) Hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) were incubated with or without 4-AP plus KN-93 as indicated. Immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. First graph represents p-S383/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to control (Ctrl) values (*P<0.05, NS; not significantly different, n=3, t-test). Second graph represents surface β3/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to control (Ctrl) values (*P<0.05, NS; not significantly different, n=3, t-test). (C, D) Nucleofected neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT (C) and pHBBSβ3S383A (D) were incubated with or without 4-AP. Cell surface pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A subunits are labelled red. The pHluorin signal (green) represents total pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A expression (scale bar 10 μm). Graphs represent cell surface/total ratio of pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A fluorescence intensity as indicated, normalized to control (Ctrl) values (***P<0.001; NS: not significantly different, n>20 neurons; t-test).

Next, we determined whether CaMKII was responsible for the activity-dependent phosphorylation of β3S383 by using the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93. In these experiments, hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) were incubated with or without 4-AP (50 μM) plus KN-93 (4 μM) for 30 min (Figure 8B). KN-93 was added 1 min prior to application of 4-AP. Cell surface GABAA receptors were isolated and we found that blocking CaMKII activity with KN-93 prevented the activity-dependent increase in β3S383 phosphorylation (4-AP: 51.0±3.7% increase relative to control; 4-AP plus KN-93: 12.7±1.76% decrease relative to control; Figure 8B) and cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors (4-AP: 43.0±5.4% increase relative to control; 4-AP plus KN-93: 11.0±5.5% decrease relative to control; Figure 8B).

To assess whether β3S383 phosphorylation is critical for the activity-dependent increase in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors, hippocampal neurons were nucleofected with pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A (16–21 div) and were incubated with 4-AP (50 μM) for 30 min. Immunofluorescence labelling of the cell surface population of pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A (Figure 8C and D) revealed that stimulating neuronal activity resulted in an increase in pHBBSβ3WT surface expression of 24.0±2.1% (Figure 8C) with no significant change in pHBBSβ3S383A surface expression (7.0±3.0% increase relative to control; Figure 8D). Combined, these findings provide direct evidence that the activity-dependent increase in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors is dependent on Ca2+ influx through L-type channels and phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII.

Blocking neuronal activity reduces phosphorylation of β3S383 and GABAA receptor cell surface expression

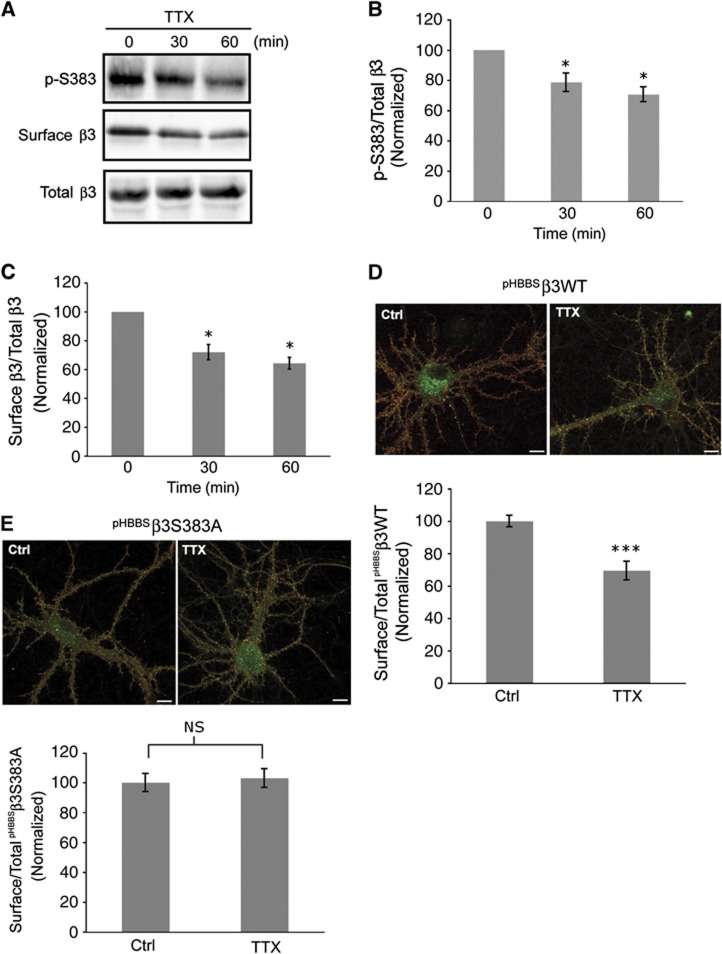

The number of synaptic GABAA receptors and the strength of GABAergic neurotransmission in dissociated cultured neurons are modulated in an adaptive response to chronic activity blockade, lasting 24 h or more (Rutherford et al, 1997; Kilman et al, 2002; Swanwick et al, 2006; Saliba et al, 2007). Since augmenting neuronal activity in cultured neurons enhances phosphorylation of β3S383 we asked whether blockade of neuronal activity has an opposite effect on β3S383 phosphorylation and cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors. To test this hypothesis, we incubated hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) with 2 μM Tetrodotoxin (TTX) for 30 and 60 min. Immunoblotting lysates with anti-p-S383 IgGs revealed that phosphorylation of β3S383 decreased by 20.5±1.5% at 30 min and by 30.4±2.8% at 60 min (Figure 9A and B) following activity blockade with TTX. Given activity blockade leads to a reduction in β3S383 phosphorylation, we next examined whether an accompanying decrease in the cell surface expression of GABAA receptors occurs, by incubating hippocampal neurons with TTX (2 μM) for 30 and 60 min. Cell surface levels of GABAA receptors were determined using a biotinylation assay and we observed a 28±3.2% decrease in cell surface expression of GABAA receptor β3 subunits following activity blockade for 30 min and a 35.7±2.3% decrease at 60 min (Figure 9A and C).

Figure 9.

Acute blockade of neuronal activity reduces phosphorylation of β3S383 and cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors. (A) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with TTX for the times indicated. Immunoblots show p-S383, surface and total β3. (B) Quantification of p-S383/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to values at time 0 (data are plotted as mean±s.e., *P<0.05; n=3; t-test). (C) Quantification of cell surface β3/total β3 band intensity ratio normalized to values at time 0 (*P<0.05; n=3; t-test). (D, E) Hippocampal neurons expressing pHBBSβ3WT (D) and pHBBSβ3S383A (E) were incubated with TTX for 60 min. Cell surface pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A subunits are labelled red and the pHluorin signal (green) represents total pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A expression (scale bar 10 μm). Graphs represent quantification of cell surface/total pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A fluorescence intensity ratios, as indicated, normalized to control (Ctrl) values (***P<0.001; NS; not significantly different, n> 20; 3 independent cultures; t test).

To determine the significance of β3S383 phosphorylation in regulating cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors following activity blockade, we incubated hippocampal neurons (16–21 div) expressing pHBBSβ3WT and pHBBSβ3S383A with TTX (2 μM) for 60 min. We observed a 29.2±4.1% decrease in cell surface pHBBSβ3WT expression levels following activity blockade (Figure 9D) but observed no significant change in pHBBSβ3S383A surface expression (6±4.4% increase relative to control; Figure 9E). Collectively, these results indicate that blocking neuronal activity results in a reduction in CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of β3S383, which is accompanied by a decrease in the cell surface expression of GABAA receptors.

Discussion

This body of work has revealed a molecular mechanism regulating GABAA receptor insertion, which is meditated by Ca2+ influx through L-type channels. Activation of L-type VGCCs leads to phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII, which facilitates the accumulation of GABAA receptors assembled with α5/β3 subunits at the cell surface and enhances tonic current. Furthermore, our studies have revealed important insights into the mechanisms underlying activity-dependent insertion of GABAA receptors. Our findings suggest that acute changes in neuronal activity lead to the rapid modulation of cell surface GABAA receptor numbers and tonic current, which is mediated by Ca2+ influx through L-type channels and CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383.

The use of a phospho-specific antibody has allowed us to assess the changes in β3S383 phosphorylation in response to Ca2+ influx through L-type channels and has enabled us to demonstrate that β3S383 is phosphorylated under basal conditions in cultured hippocampal neurons and acute hippocampal slices. Furthermore, we were able to show that acute changes in neural activity is accompanied by alterations in the levels of β3S383 phosphorylation by CaMKII which is mediated by Ca2+ influx through L-type channels. These findings are in agreement with a previous report showing that depolarization induces phosphorylation of β3S383 by CaMKII using recombinant GABAA receptors expressed in a neuronal cell line (Houston and Smart, 2006). In addition, we have shown that phosphorylation of β3S383 is critical for the activity-dependent changes in surface GABAA expression as revealed by our experiments with β3S383A.

By co-expressing a dominant-negative form of CaMKII (CaMKIIK42R) with the β3 subunit in hippocampal neurons, we have shown that this kinase plays an important role in regulating cell surface expression of GABAA receptors. Importantly, CaMKIIK42R had no influence on the surface expression of β3S383D, indicating that the effects of dominant-negative CaMKII on GABAA receptor expression rely solely on β3S383 phosphorylation. These findings are consistent with a report showing that expression of dominant negative CaMKIIK42R in cerebellar granule cells reduced the amplitude of sIPSCs (Houston et al, 2008) further supporting the model that CaMKII regulates GABAA receptor surface numbers and GABAergic neurotransmission.

Another example of phosphorylation regulating the insertion of GABAA receptors involves insulin-induced delivery of receptors to the cell surface (Wang et al, 2003b). In this study, the authors reported that phosphorylation of S410 within the intracellular loop of the GABAA receptor β2 subunit by protein kinase B (Akt) is critical for insulin-induced insertion of receptors. In our studies, we have shown using a combination of techniques to demonstrate that that Ca2+ influx through L-type channels and CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 facilitates GABAA receptor insertion without influencing receptor endocytosis.

Our findings with the β3S383 mutants that abolish or mimic phosphorylation further support a model whereby phosphorylation of β3S383 is critically involved in regulating the number of GABAA receptors at the cell surface and tonic current. Furthermore, as the total expression levels of β3S383A and β3S383D are different, this may suggest that phosphorylation of β3S383 may also regulate the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of β3.

The activity-dependent increase in β3S383 phosphorylation and cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors was completely blocked with nimodipine. These findings strongly suggest that activation of L-type channels is necessary and sufficient to mediate the effects of increased neuronal activity on β3S383 phosphorylation and the numbers of cell surface GABAA receptors. These observations may also imply that under these experimental conditions, activation of synaptic NMDA receptors appear to have no influence on the forward trafficking of GABAA receptors.

Recently, it has been reported that an increase in the diffusion coefficient of quantum dot labelled GABAA receptor molecules occurs within minutes following stimulation of neurons with either 4-AP or NMDA with an accompanying reduction in the amplitude of miniature IPSCs (Bannai et al, 2009). In a recent complimentary study, activation of NMDA receptors causes a rapid increase in surface mobility of individual GABAA receptors and a rapid dispersal of synaptic receptor clusters (Muir et al, 2010). These observations were dependent on dephosphorylation of S327 within the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor by calcineurin. In the report by Bannai et al, the authors also assessed cell surface numbers of synaptic GABAA receptors using immunofluorescence labelling, after a 2-h incubation with 4-AP and observed a substantial decrease in synaptic receptor expression. The length of time used in stimulating neural activity is an important factor to consider when assessing changes in cell surface numbers of GABAA receptors. In our experiments, we used 4-AP for shorter periods (0–30 min) before assaying cell surface expression of GABAA receptors. However, in agreement with Bannai et al, 2009 we also observed a decrease in GABAA cell surface expression following a 2-h incubation with 4-AP (unpublished observations). In another study activation of NMDA receptors (for 3 min) in a cell culture model of LTD of excitatory synapses (Marsden et al, 2007), GABAA receptor cell surface insertion and expression were reported to increase under these experimental conditions. In this report, however, surface GABAA receptor numbers were assayed following a 15-min recovery period after NMDA application. It is plausible that during this recovery period, an increase in neuronal activity would be expected, as a result of prior NMDA application leading to activity-dependent activation of L-type VGCCs. In fact, our work shows that a 5-min application of NMDA to neuronal cultures induces a rapid and almost complete dephosphorylation of β3S383 by calcineurin. This is in agreement with previous studies showing that NMDA receptor activation promotes dephosphorylation of other GABAA receptor subunits by calcineurin (Lu et al, 2000; Wang et al, 2003a; Muir et al, 2010). Thus, it appears that activity-dependent regulation of GABAA receptor insertion is critically dependent on experimental conditions and dependent on the length of time that neuronal activity is stimulated.

Changes in CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of β3S383 may have important implications for the understanding of certain neurological disorders. For example, it has been reported in a number of studies that CaMKII expression or activity is reduced in a series of in-vivo and in-vitro models of epilepsy (Delorenzo et al, 2005). Interestingly, induction of epileptiform activity in cultured hippocampal neurons exposed to low Mg2+ results in a marked reduction in β3S383 phosphorylation and cell surface expression of GABAA receptors when assayed 24 h later (unpublished observations). Furthermore, the neurodevelopmental disorder Angelman’s syndrome has been linked to compromised CaMKII activity (Weeber et al, 2003) in a mouse model of the disorder (Jiang et al, 1998) and mice lacking the GABAA receptor β3 subunit express many of the characteristics of Angelman’s syndrome and develop epilepsy (DeLorey et al, 1998). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that reduced CaMKII phosphorylation of β3S383 may be responsible for some of the phenotypic traits observed in Angelman’s syndrome.

In addition to synaptic scaling of the strength of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission, the intrinsic excitability of neurons (i.e., voltage-dependent conductances) can also be altered in response to changes in neuronal activity, which represents an additional homeostatic mechanism (Nelson and Turrigiano, 2008). Evidence shows that low concentrations of ambient GABA can continuously activate extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, to produce an inhibitory tonic conductance (Farrant and Nusser, 2005), therefore regulating the intrinsic excitability of a neuron (Mody, 2005). As our studies have shown that phosphorylation of β3S383 can be regulated by acute bi-directional changes in neuronal activity leading to the modulation of GABAA receptor expression and tonic current, this pathway seems to represent a compensatory homeostatic mechanism maintaining a normal level of intrinsic excitability in response to changes in activity. Finally, the role of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in a number of neuropsychiatric diseases is becoming apparent (Brickley and Mody, 2012) and understanding the cellular mechanisms, which modulate tonic current will benefit this expanding field.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

4-AP, TTX, Bay K 8644, nimodipine and Tubocurarine were purchased from Tocris. Rabbit polyclonal anti-β3-specific IgGs and anti-phospho β3S408/9 have been described previously (Jovanovic et al, 2004). Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP IgGs were obtained from Synaptic Systems. Secondary peroxidase-conjugated IgGs and secondary Rhodamine Red-X-conjugated IgGs were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories and Alexa-594 α-bungarotoxin was purchased from Invitrogen.

Anti-phosphorylation β3S383-specific IgGs and immunoblot analysis

The phospho-peptide CQYRKQSpMPKEG was synthesized and purchased from Alpha Diagnostic International and Cocalico Biologicals raised rabbit anti-sera to CQYRKQSpMPKEG conjugated to keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) from Pierce. Please also see Supplementary data.

Constructs

The GABAA receptor β3 subunit tagged with pHluorin and the BBS has been described previously (Bogdanov et al, 2006; Saliba et al, 2007). For the generation of pHBBSS383A and pHBBSS383D constructs, please see Supplementary data.

Neuronal cell culture, nucleofection and transfection

Hippocampal neurons were obtained as described previously (Saliba et al, 2009). Please also see Supplementary data.

Biotinylation

Neurons were biotinylated as described previously (Saliba et al, 2007). Please also see Supplementary data.

Immunocytochemistry

Neurons were immunolabelled as described previously (Saliba et al, 2009). Please also see Supplementary data.

GABAA receptor pHBBSβ3WT insertion Assay

Insertion assays were performed as described previously (Saliba et al, 2009). Please also see Supplementary data.

Hippocampal slice preparation

Slices were prepared from C57Bl6 male mice 8–12 weeks old (Terunuma et al, 2008). Please also see Supplementary data.

Electrophysiology

Hippocampal neurons were either nucleofected with pHluorin-tagged constructs (pHBBSβ3WT, pHBBSβ3S383A and pHBBSβ3S383D) or not nucleofected and plated on 12-mm glass coverslips (German glass; VWR, Bridgeport, NJ) coated with poly-L-lysine (2 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and cultured for 2–3 weeks prior to taking recordings. To measure tonic current, coverslips were placed in recording chamber mounted on the stage of inverted microscope and continuously perfused with extracellular solution of the following composition (in mM): NaCl 150, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, HEPES 10 and glucose 11, adjusted to pH 7.4 by NaOH, osmolality 295–315 mmol/kg. Excitatory and action potentials were blocked by addition of 10 μM DNQX, 25 μM D-AP5 and 0.3 μM TTX (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO). The bath solution was heated to 32–33°C by in-line heater (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM): CsCl 150, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 0.1, HEPES 10, EGTA 1.1, Mg-ATP 2, adjusted to pH 7.2 by CsOH, osmolality 275–290 mmol/kg. For neurons nucleofected with pHBBSβ3 constructs (Wt, S383A and S383D), the intracellular concentration of chloride ions was lowered to 29.2 mM by replacing 125 mM of CsCl by Cs-methanesulfonate. After establishing whole cell, period of 3 min was left to stabilize recordings prior collecting data. Recordings were made at a holding potential of −70 mV. The currents were recorded using Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), low-pass filtered at to 2 kHz, digitized (10 kHz; Digidata 1320A; Molecular Devices) and stored on computer for off-line analysis. Access resistance (<15 MΩ; 65–75% compensation) was monitored throughout the recordings and data from the cell were discarded when change >20% occurred. For tonic current measurements, an all-points histogram was plotted for a 10-s period immediately before and during application of either inhibitors (picrotoxin, bicuculline) or positive allosteric modulators (flurazepam, etomidate) of GABAA receptors. Tonic currents are represented as the change in baseline amplitude.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US National Institute of Mental Health grant 1R03MH087789-01 awarded to RSS. This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant NS036296 awarded to SJM.

Author contributions: RSS designed and performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper; KK designed and performed electrophysiology experiments, analysed data and wrote parts of the paper. SJM supervised the project and edited the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguayo LG, Espinoza F, Kunos G, Satin LS (1998) Effects of intracellular calcium on GABAA receptors in mouse cortical neurons. Pflugers Arch 435: 382–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai H, Levi S, Schweizer C, Inoue T, Launey T, Racine V, Sibarita JB, Mikoshiba K, Triller A (2009) Activity-dependent tuning of inhibitory neurotransmission based on GABAAR diffusion dynamics. Neuron 62: 670–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechem M, Hoffmann H (1993) The molecular mode of action of the Ca agonist (−) BAY K 8644 on the cardiac Ca channel. Pflugers Arch 424: 343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov Y, Michels G, Armstrong-Gold C, Haydon PG, Lindstrom J, Pangalos M, Moss SJ (2006) Synaptic GABAA receptors are directly recruited from their extrasynaptic counterparts. EMBO J 25: 4381–4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley SG, Mody I (2012) Extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron 73: 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You-Ten KE, Cheng VY, Belelli D, Newell JG, Jackson MF, Lambert JJ, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, MacDonald JF, Orser BA (2004) Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 3662–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, Kim JH, Mount HT, Taverna FA, Roder JC, Macdonald JF, Bhambri A, Collinson N, Wafford KA, Orser BA (2006) Alpha5GABAA receptors mediate the amnestic but not sedative-hypnotic effects of the general anesthetic etomidate. J Neurosci 26: 3713–3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS (2005) Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintenance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther 105: 229–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorey TM, Handforth A, Anagnostaras SG, Homanics GE, Minassian BA, Asatourian A, Fanselow MS, Delgado-Escueta A, Ellison GD, Olsen RW (1998) Mice lacking the beta3 subunit of the GABAA receptor have the epilepsy phenotype and many of the behavioral characteristics of Angelman syndrome. J Neurosci 18: 8505–8514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z (2005) Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 215–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Johnson DK, Mohler H, Rudolph U (1998) Independent assembly and subcellular targeting of GABA(A)-receptor subtypes demonstrated in mouse hippocampal and olfactory neurons in vivo. Neurosci Lett 249: 99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H (1995) GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol 359: 154–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman KN, Pal SK, Burrone J, Murthy VN (2006) Activity-dependent regulation of inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci 9: 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston CM, Hosie AM, Smart TG (2008) Distinct regulation of beta2 and beta3 subunit-containing cerebellar synaptic GABAA receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci 28: 7574–7584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston CM, Lee HH, Hosie AM, Moss SJ, Smart TG (2007) Identification of the sites for CaMK-II-dependent phosphorylation of GABA(A) receptors. J Biol Chem 282: 17855–17865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston CM, Smart TG (2006) CaMK-II modulation of GABA(A) receptors expressed in HEK293, NG108-15 and rat cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J Neurosci 24: 2504–2514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob TC, Bogdanov YD, Magnus C, Saliba RS, Kittler JT, Haydon PG, Moss SJ (2005) Gephyrin regulates the cell surface dynamics of synaptic GABAA receptors. J Neurosci 25: 10469–10478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob TC, Moss SJ, Jurd R (2008) GABA(A) receptor trafficking and its role in the dynamic modulation of neuronal inhibition. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 331–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob TC, Wan Q, Vithlani M, Saliba RS, Succol F, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ (2009) GABA(A) receptor membrane trafficking regulates spine maturity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 12500–12505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YH, Armstrong D, Albrecht U, Atkins CM, Noebels JL, Eichele G, Sweatt JD, Beaudet AL (1998) Mutation of the Angelman ubiquitin ligase in mice causes increased cytoplasmic p53 and deficits of contextual learning and long-term potentiation. Neuron 21: 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Thomas P, Kittler JT, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2004) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates fast synaptic inhibition by regulating GABA(A) receptor phosphorylation, activity, and cell-surface stability. J Neurosci 24: 522–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilman V, van Rossum MC, Turrigiano GG (2002) Activity deprivation reduces miniature IPSC amplitude by decreasing the number of postsynaptic GABA(A) receptors clustered at neocortical synapses. J Neurosci 22: 1328–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler JT, Chen G, Honing S, Bogdanov Y, McAinsh K, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Jovanovic JN, Pangalos MN, Haucke V, Yan Z, Moss SJ (2005) Phospho-dependent binding of the clathrin AP2 adaptor complex to GABAA receptors regulates the efficacy of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14871–14876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler JT, Delmas P, Jovanovic JN, Brown DA, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2000) Constitutive endocytosis of GABAA receptors by an association with the adaptin AP2 complex modulates inhibitory synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 20: 7972–7977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler JT, Thomas P, Tretter V, Bogdanov YD, Haucke V, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2004) Huntingtin-associated protein 1 regulates inhibitory synaptic transmission by modulating gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor membrane trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12736–12741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YM, Mansuy IM, Kandel ER, Roder J (2000) Calcineurin-mediated LTD of GABAergic inhibition underlies the increased excitability of CA1 neurons associated with LTP. Neuron 26: 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden KC, Beattie JB, Friedenthal J, Carroll RC (2007) NMDA receptor activation potentiates inhibitory transmission through GABA receptor-associated protein-dependent exocytosis of GABA(A) receptors. J Neurosci 27: 14326–14337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BJ, Moss SJ (1994) Differential phosphorylation of intracellular domains of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunits by calcium/calmodulin type 2-dependent protein kinase and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 269: 18111–18117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BJ, Moss SJ (1997) Conserved phosphorylation of the intracellular domains of GABA(A) receptor beta2 and beta3 subunits by cAMP-dependent protein kinase, cGMP-dependent protein kinase protein kinase C and Ca2+/calmodulin type II-dependent protein kinase. Neuropharmacology 36: 1377–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I (2005) Aspects of the homeostatic plasticity of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. J Physiol 562: 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss SJ, Smart TG (2001) Constructing inhibitory synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 240–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir J, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, MacAskill AF, Smith KR, Griffin LD, Kittler JT (2010) NMDA receptors regulate GABAA receptor lateral mobility and clustering at inhibitory synapses through serine 327 on the gamma2 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 16679–16684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG (2008) Strength through diversity. Neuron 60: 477–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Sieghart W (2009) GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology 56: 141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Mohler H (2004) Analysis of GABAA receptor function and dissection of the pharmacology of benzodiazepines and general anesthetics through mouse genetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44: 475–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford LC, DeWan A, Lauer HM, Turrigiano GG (1997) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates the activity-dependent regulation of inhibition in neocortical cultures. J Neurosci 17: 4527–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba RS, Gu Z, Yan Z, Moss SJ (2009) Blocking L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels with dihydropyridines reduces gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor expression and synaptic inhibition. J Biol Chem 284: 32544–32550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba RS, Michels G, Jacob TC, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ (2007) Activity-dependent ubiquitination of GABA(A) receptors regulates their accumulation at synaptic sites. J Neurosci 27: 13341–13351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W (1997) GABA(A) receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus I: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience 80: 987–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur C, Quirk K, Dewar D, Atack J, McKernan R (1998) Rat and human hippocampal alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric Acid A receptors have alpha5 beta3 gamma2 pharmacological characteristics. Mol Pharmacol 54: 928–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick CC, Murthy NR, Kapur J (2006) Activity-dependent scaling of GABAergic synapse strength is regulated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Mol Cell Neurosci 31: 481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terunuma M, Xu J, Vithlani M, Sieghart W, Kittler J, Pangalos M, Haydon PG, Coulter DA, Moss SJ (2008) Deficits in phosphorylation of GABA(A) receptors by intimately associated protein kinase C activity underlie compromised synaptic inhibition during status epilepticus. J Neurosci 28: 376–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Mortensen M, Hosie AM, Smart TG (2005) Dynamic mobility of functional GABAA receptors at inhibitory synapses. Nat Neurosci 8: 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithlani M, Moss SJ (2009) The role of GABAAR phosphorylation in the construction of inhibitory synapses and the efficacy of neuronal inhibition. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 1355–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu S, Haditsch U, Tu W, Cochrane K, Ahmadian G, Tran L, Paw J, Wang Y, Mansuy I, Salter MM, Lu YM (2003a) Interaction of calcineurin and type-A GABA receptor gamma 2 subunits produces long-term depression at CA1 inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci 23: 826–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu L, Pei L, Ju W, Ahmadian G, Lu J, Wang Y, Liu F, Wang YT (2003b) Control of synaptic strength, a novel function of Akt. Neuron 38: 915–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RA, Cheng G, Kolaj M, Randic M (1995) Alpha-subunit of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid and inhibitory synaptic responses of rat neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 73: 2099–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeber EJ, Jiang YH, Elgersma Y, Varga AW, Carrasquillo Y, Brown SE, Christian JM, Mirnikjoo B, Silva A, Beaudet AL, Sweatt JD (2003) Derangements of hippocampal calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in a mouse model for Angelman mental retardation syndrome. J Neurosci 23: 2634–2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Zhang M, Zhu Y, Wang JH (2004) Ca(2+)-calmodulin signalling pathway up-regulates GABA synaptic transmission through cytoskeleton-mediated mechanisms. Neuroscience 127: 637–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.