Abstract

Mithramycin is an antitumor compound produced by Streptomyces argillaceus that has been used for the treatment of several types of tumors and hypercalcaemia processes. However, its use in humans has been limited because its side effects. Using combinatorial biosynthesis approaches, we have generated seven new mithramycin derivatives, which either differ from the parental compound in the sugar profile or in both the sugar profile and the 3-side chain. From these studies three novel derivatives were identified, demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK, demycarosyl-mithramycin SDK and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SDK, which show high antitumor activity. The first one, which combines two structural features previously found to improve pharmacological behavior, was generated following two different strategies, and it showed less toxicity than mithramycin. Preliminary in vivo evaluation of its antitumor activity through hollow fiber assays, and in subcutaneous colon and melanoma cancers xenografts models, suggests that demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK could be a promising antitumor agent, worthy of further investigation.

Keywords: Streptomyces, antitumor, mithramycin, mithramycin SK, combinatorial biosynthesis, digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the most threatening illnesses in western countries, being the second cause of death. One of the therapies used for treating cancer is chemotherapy. Although there are a rather high number of anticancer drugs for clinical use, there is still a demand for novel drugs with less toxicity and higher activity and/or active against tumors which lack an appropriate treatment.

Transcription factors (TFs) are nodal points in signal transduction pathways that have to lead to transcriptional changes in order to affect cell behaviour. Aberrant activity of TFs is a hallmark in many cancers, as result of direct genetic events (e. g. gene translocations) or secondary to other events (e. g. kinase/receptor mutations). There is proof of concept evidence, using both in vitro and in vivo models, that targeting TFs has clear therapeutic benefit in cancer, as for example, STAT3 inhibitors; p53 targeted small molecules (to restore the transcriptional activity of mutated p53); NF-κB; myc targeted oligonucleotides and much more.1,2 Limited evidence of efficacy in clinical trials exists, although some TF antagonists (STAT3, -κB) are progressing through phase 1-2 trials.3,4

Sp1 is a TF that controls many critical processes in cells (proliferation, survival, stress responses). It is present in many normal cells, but is abnormally expressed or activated in many cancers.3 Some researchers are looking for Sp1 transcriptional signatures in cancers (like prostate, ovarian cancer). Preliminary data show up-regulation of many Sp1 target genes in tumors compared to normal cells, even if Sp1 itself is not up-regulated, indicating activation of Sp1.5,6 Similar to other TFs, proof of concept exists that targeting Sp1 with antisense oligonucleotides, siRNA, decoy oligonucleotides has therapeutic benefit. Also, indirect targeting of Sp1 with drugs like cox2 inhibitors and others has been shown to have therapeutic effects.7

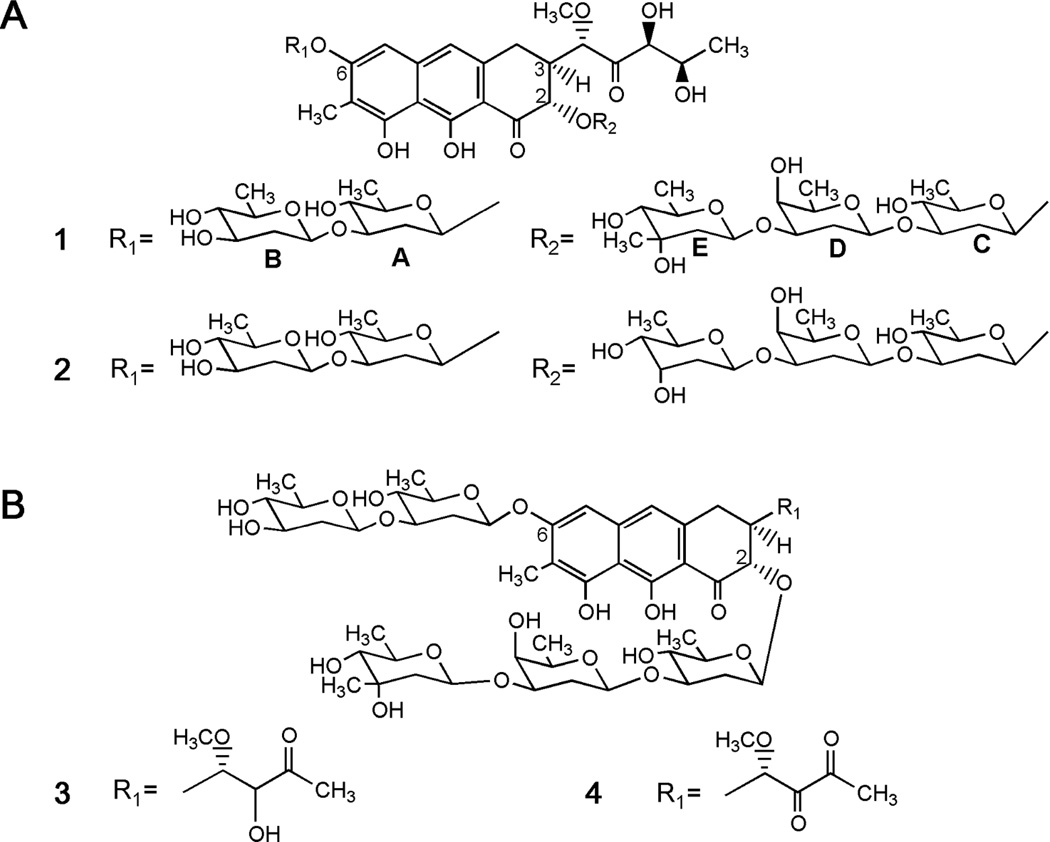

Mithramycin (1, Figure 1A) is a DNA binding agent with relative specificity for Sp1, based on their preferential binding to GC-rich sites in DNA. It was discovered in 1961 and approved for use as anticancer drug in 1970.8 Despite showing strong response rates, it has not been in use in recent years for cancer treatment due to its adverse effects. The problems with 1 derive from the lack of a suitable therapeutic window, so the active doses are those that unfortunately cause toxic side effects.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (A) mithramycin (1) and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin (2), and (B) mithramycin SK (3) and mithramycin SDK (4).

Notwithstanding, in recent years there has been a renewed interest in 1, since new uses and activities have been ascribed to it, including inhibition of apoptosis or antiangiogenic activity, in both cancer and non-cancer related processes.9–11 For example, it has been shown that 1 selectively blocks expression of cell proliferation and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signalling clusters in human gingival fibroblasts, and in glioma cells it was found to suppress and delay tumor cell migration;12,13 also, 1 supresses the growth of Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (ESFTs) xenografts-bearing mice. In this context, 1 was identified in a screening of 50,000 compounds as the lead compound for the inhibition of aggressive ESFTs, for its in vitro and in vivo inhibition of the Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 and Friend leukemia virus integration 1 (EWS-FLI1) TF, a protein that had previously been thought to be undruggable.14 This indicates that 1 could be a viable drug for certain indications, despite its very narrow therapeutic window.

The mithramycin mode of action involves its interaction in a noncovalently way with GC-rich DNA regions located at the minor groove of DNA.15–19 By doing so, it prevents transcription factor Sp1 from binding to a variety of promoters of proto-oncogenes, genes involved in angiogenesis, antiapoptotic genes, p53-mediated transcriptional responses, as well as multidrug resistant gene 1 (MDR-1).20–24 Recent work has shown that 1 does not equally bind all Sp1 binding sites: it inhibits Sp1 binding to a subset of genes associated with oncogenesis, but selectively ignores Sp1 binding sites in other promoters such as p21cip1/waf1, which are classically linked with tumor suppression.25 Most important, the recent work of Grohar et al. also shows that mithramycins can target cancer-related TFs, which adds a novel component of potential selectivity to the aureolic acids class of anticancer drugs.14

Structurally, 1 consists of a tricyclic aglycone with two aliphatic side chains attached at C3 and C7, and a trisaccharide (D-olivose-d-oliose-d-mycarose) and a disaccharide (D-olivose-d-olivose) chains attached at positions two and six of the aglycone, respectively.26 The mithramycin gene cluster of Streptomyces argillaceus has been cloned and characterized, and its biosynthesis pathway has been established (see Ref. 27 for a review). The aglycone is synthesized through the condensation of one acetyl-CoA and nine malonyl-CoA units to render a carbon chain, which is then aromatized, cyclized, oxygenated, and methylated. Then, the resultant tetracyclic intermediate is sequentially glycosylated, followed by the oxidative cleavage of the fourth ring, and the reduction of the carbon side chain attached at 3-position, to render the final compound 1. We have applied different strategies of combinatorial biosynthesis in order to generate novel derivatives of 1 with antitumor activity.28–32 Some of these compounds (see Figure 1, compounds 2–4) showed high antitumor activity, and either exhibited new glycosylation profiles,30–32 or contained structural changes affecting the pentyl side chain attached at 3-position.5,29,33 Interestingly, analogues with modifications at the 3-carbon side chain showed higher antitumor activity than the parental compound, and delayed growth of ovarian tumor xenografts.5,6,29,33

Here we further explored the generation of new mithramycin analogues by applying combinatorial biosynthesis strategies to S. argillaceus, aiming on new compounds that either differ from the parental compound in the sugar profile or in both the sugar profile and the 3-side chain. From these studies three novel derivatives emerged, named demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK, demycarosyl-mithramycin SDK and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SDK, which show high antitumor activity. The first one, which combines two structural features previously found to improve mithramycin pharmacological behavior, was less toxic than the parental compound, and was evaluated on tumor growth in hollow fiber assays, and for treatment of colon and melanoma cancers using human tumors xenografts in murine models in nude mice.

RESULTS

Generation of novel mithramycin analogues

Two types of mithramycin analogues were generated: mithramycins with modified glycosylation profile, and compounds with both specific modifications in the glycosylation pattern and at the 3-carbon side chain. It has been shown that sugars in 1 participate in the binding process of this compound to DNA,34,35 and that changes in the glycosylation profile of 1 can affect its activity.30,31 Modifications in the glycosylation pattern of a molecule by combinatorial biosynthesis can be achieved using different approaches, such as expressing plasmids directing the biosynthesis of a different sugar into the producer organism.36 Moreover, the use of a mutant affected in the biosynthesis of a normal component sugar of the compound as host, can increase the chances to generate compounds with new glycosylation profiles.31

In order to facilitate the generation of mithramycins with different glycosylated profiles, we used as a host the S. argillaceus mutant M7C1 in which the mtmC gene had been inactivated.37 This mutant accumulates some compounds lacking the d-mycarose residue and possessing a 4-ketosugar moiety instead of the d-olivose at the beginning of the trisaccharide chain, since in this mutant d-mycarose biosynthesis is blocked and the biosynthesis of d-olivose is altered.38 To endow this mutant with the capability of synthesizing new sugars, we expressed pFL84539 in mutant M7C1. This plasmid encodes the biosynthesis of d-amicetose, a sugar not present in 1, and that of d-olivose, which is altered in the mutant strain. Analysis of the resultant strain S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845 by HPLC and HPLC-MS, revealed the production of several mithramycin-like compounds (see Supporting Information). The major one corresponded to the previously identified demycarosyl-mithramycin, 31 a compound with identical structure than 1, but lacking d-mycarose, the biosynthesis of which is blocked in this mutant. Compounds from the other peaks showed retention times and masses that did not fit with those of previously identified mithramycin analogues, and most probably corresponded to novel mithramycin derivatives, which were later identified as dideolivosyl-6-β-Damicetosyl-demycarosyl-2-O-β-d-oliosyl-3C-β-d-olivosyl-mithramycin (5), dideolivosyl-6-β-Damicetosyl-demycarosyl-mithramycin (6), deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (7) and dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (8).

A second type of mithramycin analogues was generated, aiming on compounds with modifications in the glycosylation pattern and the 3-carbon side chain. We have previously shown that by inactivating the mtmW gene (encoding for a ketoreductase), several mithramycins were generated with modifications in the 3-carbon side chain that showed improved antitumor activities.29 On the other hand, we have also obtained several mithramycins with antitumor activity with modifications in the glycosylation pattern, among which the most active one was demycarosyl-3D-β-Ddigitoxosyl-mithramycin (compound 2 in Figure 1A).30,31 On the basis of this information, we set out to generate mithramycin derivatives containing both type of structural features in the molecule and expecting to improve the antitumor properties in relation to the parental compound. To achieve this, we provided to the S. argillaceus mutant M3W129 (which produces mithramycins with modifications at the carbon side chain), with the capability to synthesize d-digitoxose, (i) by expressing plasmid pMP3*BII, 40 and (ii) by expressing plasmid pKOL.

Plasmid pMP3*BII encodes the biosynthesis of NDP-d-digitoxose. Analysis by HPLC and HPLC-MS of ethyl acetate extracts of cultures of the resultant strain S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII revealed the production of four compounds, in addition to mithramycin SK (compound 3 in Figure 1B) and mithramycin SDK (compound 4 in Figure 1B), originally produced by mutant M3W1 (see Supporting Information). One of these compounds corresponded to the previously identified demycarosyl-mithramycin SK,29 while retention times and masses from the other three indicated most probably novel compounds, and were subsequently identified as demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK (9), demycarosyl-mithramycin SDK (10) and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SDK (11).

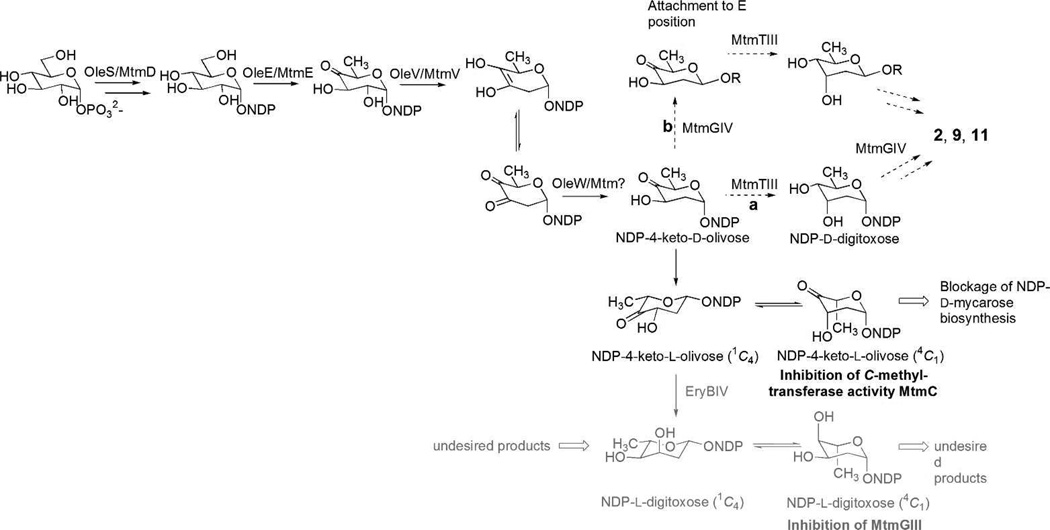

From the attempts to generate new 1-analogues through heterologous expression of “deoxysugar plasmids” that encode NDP-activated deoxyhexose pathways in wild type Streptomyces argillaceus, overexpression of plasmid pLNBIV was most successful. This plasmid encodes the biosynthesis of both NDP-d- and NDP-l-digitoxose (Scheme 1), and its expression resulted in the accumulation of new mithramycin compounds containing digitoxose. One of the mithramycins accumulated, demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin (compound 2 in Figure 1A) featured a d-digitoxose substituting the d-mycarose normally found in the E-position of the trisaccharide chain.30 Plasmid pKOL is a derivative of pLN2 and encodes predominantly the biosynthesis of NDP-4-keto-d-olivose. It resembles plasmid pLBIV, the plasmid previously used for the generation of demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin (2),30 but lacks ketoreductase EryBIV, thereby avoiding the formation of NDP-l-digitoxose, which led to the production of several undesirable analogues (Scheme 1).30 We reasoned that pKOL’s main product, NDP-4-keto-d-olivose, would be reduced selectively by ketoreductase MtmTIII into d-digitoxose, either prior or after its incorporation into the E-position (Scheme 1). MtmTIII had been identified as being responsible for the 4-ketoreduction of the d-mycarose building block, generating simultaneously an equatorial OH-group in 4- and an axial OH-group in 3-position of the sugar during 1-biosynthesis. However, it remained unclear whether MtmTIII acts prior or after the incorporation of the sugar in E-position.38 Furthermore, we expected that pKOL’s second product, NDP-4-keto-l-olivose, would partly inhibit the C-methyltransferase activity of MtmC, thereby reducing the d-mycarose production (Scheme 1). Indeed, expressing pKOL resulted in a significantly increased accumulation of demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin (2) in fermentations of Streptomyces argillaceus (pKOL), and in the production of two new compounds, subsequently identified as compounds 9 and 11 in fermentations of Streptomyces argillaceus M3W1-pKOL (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 1.

Depictions of deoxysugar biosynthesis pathways encoded by pLNBIV (NDP-l-digitoxose, gray, solid arrows) and pKOL (NDP-4-keto-d-olivose, black, dotted arrows) and observed outcomes.

Purification and structural elucidation of new mithramycin analogues

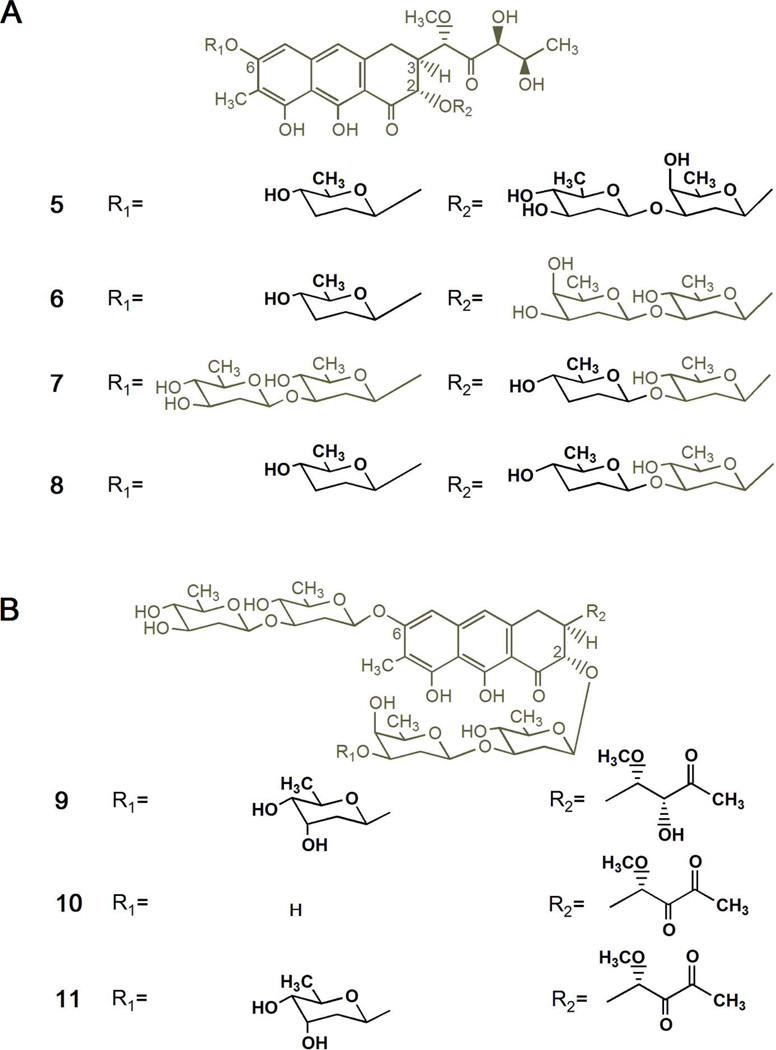

Four new compounds were purified from S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845 (compounds 5–8). Purification was carried out by preparative HPLC and the novel compounds were initially identified by HPLC-MS analyses by comparing the retention time, UV absortion spectrum and the mass of the molecular ion with those of already known mithramycin analogues. A preliminary analysis based on the mass spectra showed that the four compounds isolated from S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845 presented the typical fragment ascribed to the aglycone moiety of 1 (m/z: 420). Likewise, the mass of the molecular ions revealed the absence of one or two sugar residues respect to 1. Final elucidation of the compounds was carried out by NMR experiments; spin systems of each single sugar moiety were analyzed by means of H,H-COSY and TOCSY experiments and both sugar-aglycone and inter-sugar connections were established through HMBC experiments. Further 1H homo decoupling experiments allowed the unambiguous identification of each sugar. Regarding compound 7, its 1H spectrum revealed not only the absence of the sugar E but also a different profile for the sugar D, typically occupied by a d-oliose residue in mithramycin derivatives. Thus, analysis of the 2D COSY/TOCSY experiments revealed a spin system stretching from 1-H to 6-H, with two protons attached to the 3D position (δHax 1.60 ppm and δHeq 2.05 ppm). Due to the overlapping and complexity of the signals of 2D-Hax, 2D-Heq, 3D-Hax, 3D-Heq, 4D-H and 5D, 1H homo decoupling experiments were required to establish the sugar D as a d-amicetose unit, concluding the identity of 7 as deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (compound 7, Figure 2A). The mass spectra of 5, 6 and 8 were consistent with mithramycin analogues harboring only three sugar residues. For example, compound 8 lacked the sugars B and E (confirmed by comparison with previously described compounds, and also due to the absence of inter-sugar connections for 3A and 3D in the HMBC spectra). Moreover, both sugars A and D were identified as d-amicetoses as above detailed for 7, allowing to confirm the structure of 8 as dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (compound 8, Figure 2A). Regarding 6 and 5, they showed identical molecular ion peaks and fragmentations in the mass spectra. The 1H and 13C spectra showed the absence of the sugar B and a pattern typical of β-d-amicetose for the A sugar in both cases. The other two remaining sugars (C and D) were identified as β-d-olivose and β-d-oliose units. In the case of 6, as revealed by the HMBC long-range couplings, the β-d-olivosyl residue was directly attached to the aglycone moiety. Thus, it was observed cross-peaks between H-1C (δ5.14) and C-2 (δ76.6) as well as between C-3C (δ 81.3) and H-1D (δ 4.70), allowing to establish 6 as dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-demycarosyl-mithramycin (compound 6, Figure 2A). On the contrary, 5 was connected to the aglycone moiety towards the β-d-oliosyl residue (according to HMBC analysis) and turned out to be dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-demycarosyl-2-O-β-d-oliosyl-3C-β-d-olivosyl-mithramycin (compound 5, Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of new mithramycin analogues generated by combinatorial biosynthesis. (A) Compounds with modified glycosylation patterns produced by S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845: dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-demycarosyl-2-O-β-d-oliosyl-3C-β-d-olivosyl-mithramycin (5), dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-demycarosyl-mithramycin (6), deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (7), and dideolivosyl-6-β-d-amicetosyl-deoliosyl-demycarosyl-3C-β-d-amicetosyl-mithramycin (8). (B) compounds with modified glycosylation pattern and different structure of the 3-carbon side chain produced by S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP*3BII: demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK (9), demicarosyl-mithramycin SDK (10), and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SDK (11). Differences from 1 are highlighted in bold.

As anticipated, since the biosynthesis of d-mycarose is blocked in mutant M7C1, compounds 5–8 all lacked the d-mycarose residue. However, none of them incorporated another sugar instead at the same position of the trisaccharide chain. This suggests that the glycosyltransferase responsible for transferring sugar E shows limited sugar donor substrate flexibility. Actually, in all mithramycin derivatives generated so far by combinatorial biosynthesis, the third position of the trisaccharide chain is mostly occupied by d-mycarose (the natural sugar) or with less frequency by d-digitoxose, and in a single case by 4-keto-d-mycarose.30,31,38 On the other hand, all compounds contain d-olivose residues, indicating that the biosynthesis of d-olivose was restored in the mutant strain by pFL845. Moreover, in agreement with the sugar biosynthetic pathways encoded by pFL845, all new analogues incorporated one or two d-amicetose residues: at the first position of the disaccharide chain (compounds 5, 6 and 8) or the second position of the trisaccharide chain (compounds 7 and 8). Noticeably, 5 contains the same first two sugars residues at the trisaccharide chain as 1, but in the other way around; as far as we know 5 represents the first mithramycin analogue with a different sugar than d-olivose at the first position of the trisaccharide chain.

S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII produces three new compounds (compounds 9–11). These were initially identified by HPLC-MS, taking advantage of the mass of the molecular ions and the information extracted from the characteristic fragmentation pattern of the mithramycin-type compounds. In the case of 10, a molecular formula of C44H60O20 (m/z: 908) was deduced, and the analysis of fragments revealed the typical aglycone moiety of compound 4 (m/z: 388) and the disaccharide side chain (sugars A and B). Moreover, considering the absence of the trisaccharide side chain fragment (sugars C, D and E) as well as the molecular mass of 144 amu smaller than that of compound 4, 10 was tentatively established as demycarosyl-mithramycin SDK, lacking the sugar E of the parental compound. Regarding 9 and 11, they showed molecular formulas of C50H72O23 (m/z: 1040) and C50H70O23 (m/z: 1038) and fragments ascribed to the aglycone moieties of compound 3 (m/z: 390) and compound 4 (m/z: 388), respectively. In both cases, the fragment associated to the disaccharide chain remained unaltered meanwhile the fragment typical of the trisaccharide chain exhibited 14 amu less than that of the parental compounds, suggesting a non-C-methylated dideoxy sugar for the sugar E. Compounds 9–11 were unambiguously elucidated by mono- and bidimensional NMR experiments, including 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, HMBC and NOESY, and comparing the corresponding spectra with those previously described for the parental 3 and 4. In the case of 10, NMR spectra were identical to those of 4 but lacking of all the signals attached to the sugar E, the molecule being confirmed as demycarosyl-mithramycin SDK (compound 10, Figure 2B). Regarding 9 and 11, the signals of the aglycone moiety, the disaccharide side chain (sugars A and B), and sugar units C and D of the trisaccharide chain in the 1H-NMR spectra showed an analogous profile to the corresponding moieties of 3 and 4, respectively, while the difference was found in sugar E. Analysis of 2D COSY contour plots in conjunction with 1D spectra revealed a coupling of both 2E-Hax and 2E-Heq protons with a proton in 3E, indicating that the 3E-CH3 is missing (according to our previous findings in HPLC-MS). Moreover, the appearance of this 3E-H as a broad signal (singlet in 9 or doublet in 11, with small coupling constants) was indicative of an equatorial position. The 13C NMR data confirmed the disappearance of the 3E-CH3 signal as well as the exchange of the previous 3E-C quaternary center of 3 and 4 by a novel tertiary carbon (δ67.8 ppm). Overall, careful analysis of the 2D COSY correlations between 2E-Heq, 2E-Hax, 4E-H and 3E-H and their coupling constants allowed us to establish the d-digitoxose stereochemistry (correlating well with the digitoxose signals of the known compound 2), 9 and 11 being identified as demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SK and demycarosyl-3D-β-d-digitoxosyl-mithramycin SDK, respectively (Figure 2B). In conclusion and as it was anticipated, strain S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII produced new compounds combining modifications at the 3-carbon side chain and in the glycosylation profile (Figure 2B): compound 9 a 2-hydroxy-1-methoxy-3-oxobutyl side chain (compound 3-like),29 while 10 and 11 a 1-methoxy-2,3-dioxobutyl side chain (compound 4-like);5 in addition, in compounds 9 and 11 the d-mycarose residue was replaced by d-digitoxose, and in 10 the third sugar in the trisaccharide chain was absent.

The expression of plasmid pKOL in mutant strain S. argillaceus M3W1, resulting in recombinant strain S. argillaceus M3W1-pKOL produced several mithramycin-type compounds, including the known metabolites 3 and 4 and demycarosyl-mithramycin SK.5,29 The two new compounds, not present in extracts of S. argillaceus M7W1, showed mithramycin-type UV absorptions and slightly faster retention times (Rt=Δ0.6 min−1) compared to 3 and 4, with masses of 14 amu less than their 3 and 4 counterparts, indicating the substitution of an unmethylated 2,6-dideoxysugar at E position (1039 amu [M-H] for the peak at Rrel=16.6 min−1 and 1037 amu [M-H] for the peak at Rrel=18.6 min−1 (-) APCI-MS). A 10L-fermentation of S. argillaceus M3W1-pKOL yielded sufficient amounts of the new compounds, which were identified through HR-ESI mass spectrometry and 1D- and 2D-NMR spectroscopy as compound 9 and 11 (Figure 2B).

Antitumor activity of new mithramycin analogues

Antitumor activity of selected new mithramycin analogues was initially tested against a panel of three tumor cell lines. Only compounds 9 to 11, which combine modifications both in the sugar moiety and C3 side chain in their structures, showed high antitumor activity, with average GI50 (50% of growth inhibition) values between 0.3 and 1.3 µM. The anti-cancer activity of compounds 9 to 11 were tested in the National Cancer Institute's cell viability screen using 60 cancer cell lines derived from different solid and liquid tumors.41 As a reference, compound 2, with only modifications in the glycosylation pattern, was also tested. Data are shown in Table 1. All three new compounds showed high antitumor activity against all human tumor cell lines tested, with GI50 values between 10 nM and 1 µM, except in ovarian tumor cell line NCI/ADR-RES where GI50 values for compounds 9 and 10 are higher than 10 µM. Compounds 9 and 11 showed the highest antitumor activity, being in average about 5-fold more active than 10. A comparison of the GI50 values of compounds 9 and 11 with those of compound 2, which only differs from them in the structure of the 3-carbon side chain, revealed an increase of activity (between two- and seven-fold) for 9 and 11 for a number of cell lines (see numbers shadowed in grey in Table 1). Compared with 1 which has average GI50 of 18 nM (according to historical data at the NCI), 9 and 11 were slight less potent (average GI50 at 30 and 28 nM, respectively), while 10 is significantly less potent, with average GI50 at 158 nM. However, 9 and 11 are more potent than 1 in a couple of cell lines spreading in different tumor types, particularly in ovarian tumor IGROV1 and breast tumor MDA-MB-231 cell lines (Table 2).

Table 1.

Antitumor analysis and comparison of compounds 9 and 11 with compound 2

| Average log(GI50) values |

comparison with 9 |

comparison with 11 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cell lines | 2 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Δ2–9 | activity improvement factora |

Δ2–11 | activity improvement factora |

|

| Leukemia | CCRF-CEM | −7.55 | −7.61 | −6.81 | −7.62 | 0.06 | 1.14 | 0.07 | 1.16 |

| HL-60(TB) | −7.27 | −7.62 | −6.87 | −7.76 | 0.35 | 2.24 | 0.49 | 3.09 | |

| K-562 | −7.61 | −7.76 | −6.82 | −7.71 | 0.15 | 1.40 | 0.10 | 1.26 | |

| MOLT-4 | −7.32 | −7.70 | −6.86 | −7.56 | 0.39 | 2.43 | 0.25 | 1.76 | |

| RPMI-8226 | −7.93 | −7.79 | −6.86 | −7.80 | −0.14 | 0.73 | −0.13 | 0.75 | |

| SR | −7.85 | −7.89 | −7.08 | −7.93 | 0.04 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 1.22 | |

| NSCLb | A549/ATCCC | −7.38 | −7.69 | −6.77 | −7.61 | 0.31 | 2.04 | 0.23 | 1.68 |

| EKVX | −6.87 | −7.07 | −6.66 | −7.04 | 0.21 | 1.60 | 0.17 | 1.48 | |

| HOP-62 | −7.25 | −7.61 | −6.86 | −7.78 | 0.36 | 2.26 | 0.53 | 3.39 | |

| HOP-92 | −7.52 | −7.57 | −6.89 | −7.70 | 0.04 | 1.11 | 0.18 | 1.50 | |

| NCI-H226 | −7.34 | −7.69 | −6.84 | −7.46 | 0.36 | 2.26 | 0.12 | 1.32 | |

| NCI-H23 | −7.38 | −7.65 | −6.95 | −7.83 | 0.27 | 1.86 | 0.45 | 2.79 | |

| NCI-H322M | −7.24 | −7.63 | −6.86 | −7.80 | 0.39 | 2.43 | 0.56 | 3.63 | |

| NCI-H460 | −7.67 | −7.75 | −6.84 | −7.75 | 0.08 | 1.19 | 0.08 | 1.19 | |

| NCI-H522 | −7.85 | −7.75 | −6.57 | −7.70 | −0.10 | 0.79 | −0.15 | 0.70 | |

| Colon | COLO 205 | −7.31 | −7.67 | −7.08 | −7.52 | 0.35 | 2.26 | 0.21 | 1.60 |

| HCC-2998 | −7.21 | −7.79 | −7.00 | −7.89 | 0.58 | 3.76 | 0.68 | 4.79 | |

| HCT-116 | −7.71 | −7.78 | −6.85 | −7.83 | 0.07 | 1.17 | 0.11 | 1.30 | |

| HCT-15 | −5.98 | −5.98 | −5.95 | −6.74 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 5.82 | |

| HT29 | −7.12 | −7.67 | −6.80 | −7.61 | 0.55 | 3.55 | 0.49 | 3.13 | |

| KM12 | −7.53 | −7.75 | −6.89 | −7.89 | 0.22 | 1.66 | 0.37 | 2.32 | |

| SW-620 | −7.53 | −7.65 | −6.88 | −7.62 | 0.12 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 1.22 | |

| CNSc | SF-268 | −7.51 | −7.65 | −6.83 | −7.73 | 0.15 | 1.40 | 0.22 | 1.66 |

| SF-295 | −7.40 | −7.70 | −6.89 | −7.77 | 0.30 | 2.00 | 0.37 | 2.32 | |

| SF-539 | −7.48 | −7.60 | −6.93 | −7.68 | 0.12 | 1.30 | 0.20 | 1.58 | |

| SNB-19 | −7.36 | −7.55 | −6.84 | −7.77 | 0.19 | 1.55 | 0.41 | 2.57 | |

| SNB-75 | −7.52 | −7.49 | −7.13 | −7.96 | −0.03 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 2.75 | |

| U251 | −7.63 | −7.73 | −6.84 | −7.76 | 0.10 | 1.26 | 0.13 | 1.35 | |

| Melanoma | LOX IMVI | −7.69 | −7.78 | −6.83 | −7.87 | 0.09 | 1.23 | 0.18 | 1.51 |

| MALME-3M | −7.62 | −7.71 | −6.95 | −7.46 | 0.09 | 1.23 | −0.16 | 0.69 | |

| M14 | −7.00 | −7.34 | −6.94 | −7.44 | 0.34 | 2.19 | 0.44 | 2.75 | |

| MDA-MB-435 | −7.37 | −7.63 | −6.98 | −7.60 | 0.26 | 1.82 | 0.23 | 1.70 | |

| SK-MEL2 | −7.47 | −7.56 | −6.71 | −7.82 | 0.09 | 1.23 | 0.35 | 2.24 | |

| SK-MEL28 | −7.56 | −7.73 | −6.94 | −7.68 | 0.16 | 1.46 | 0.11 | 1.30 | |

| SK-MEL-5 | −7.56 | −7.77 | −7.02 | −7.65 | 0.21 | 1.62 | 0.10 | 1.24 | |

| UACC-257 | −7.16 | −7.38 | −6.71 | −7.23 | 0.22 | 1.66 | 0.07 | 1.17 | |

| UACC-62 | −7.91 | −7.92 | −7.05 | −7.87 | 0.01 | 1.02 | −0.04 | 0.91 | |

| Ovarian | IGROV1 | −7.12 | −7.98 | −6.65 | −7.63 | 0.86 | 7.16 | 0.51 | 3.24 |

| OVCAR-3 | −7.16 | −7.71 | −6.84 | −7.70 | 0.55 | 3.51 | 0.54 | 3.43 | |

| OVCAR-4 | −6.68 | −7.25 | −6.78 | −7.14 | 0.57 | 3.76 | 0.46 | 2.88 | |

| OVCAR-5 | −7.10 | −7.40 | −6.82 | −7.51 | 0.30 | 1.97 | 0.41 | 2.57 | |

| OVCAR-8 | −7.27 | −7.45 | −6.70 | −7.59 | 0.18 | 1.51 | 0.32 | 2.11 | |

| NCI/ADR-RES | −5.11 | −4.30 | −4.87 | −5.78 | −0.81 | 0.15 | 0.67 | 4.68 | |

| SK-OV-3 | −6.99 | −7.58 | −6.74 | −7.60 | 0.59 | 3.85 | 0.61 | 4.03 | |

| Renal | 786-0 | −7.21 | −7.49 | −6.78 | −7.60 | 0.28 | 1.88 | 0.39 | 2.43 |

| A498 | −7.49 | −7.84 | −6.95 | −7.32 | 0.35 | 2.24 | −0.16 | 0.68 | |

| ACHN | −6.81 | −7.46 | −6.59 | −7.13 | 0.65 | 4.47 | 0.32 | 2.09 | |

| CAKI-1 | −6.64 | −6.86 | −6.44 | −6.90 | 0.22 | 1.64 | 0.26 | 1.82 | |

| RXF 393 | −7.59 | −7.53 | −7.66 | −7.87 | −0.06 | 0.86 | 0.28 | 1.91 | |

| SN12C | −7.45 | −7.68 | −6.82 | −7.61 | 0.23 | 1.70 | 0.16 | 1.45 | |

| TK-10 | −6.89 | −7.28 | −6.82 | −7.07 | 0.39 | 2.45 | 0.17 | 1.50 | |

| UO-31 | −6.78 | −7.16 | −6.44 | −6.90 | 0.38 | 2.40 | 0.11 | 1.30 | |

| Prostate | PC-3 | −7.00 | −7.67 | −6.83 | −7.64 | 0.67 | 4.62 | 0.64 | 4.37 |

| DU-145 | −7.04 | −7.69 | −6.74 | −7.60 | 0.65 | 4.47 | 0.56 | 3.63 | |

| Breast | MCF7 | −7.89 | −7.86 | −6.84 | −7.70 | −0.04 | 0.92 | −0.19 | 0.65 |

| MDA-MB-231/ATCC | −6.88 | −7.32 | −6.62 | −7.18 | 0.44 | 2.75 | 0.30 | 2.00 | |

| HS578T | −7.55 | −7.79 | −6.83 | −7.79 | 0.25 | 1.76 | 0.25 | 1.76 | |

| BT-549 | −7.77 | −7.74 | −7.06 | −7.87 | −0.03 | 0.94 | 0.10 | 1.26 | |

| T-47D | −7.35 | −7.59 | −6.91 | −7.47 | 0.24 | 1.74 | 0.12 | 1.32 | |

| MDA-MB-468 | −7.30 | −7.47 | −7.03 | −7.63 | 0.17 | 1.48 | 0.33 | 2.14 | |

| Mean log(GI50) | −7.30 | −7.52 | −6.80 | −7.55 | |||||

| Mean GI50 (nM) | 51 | 30 | 158 | 28 | |||||

The activity improvement factor is obtained from 10Δ2-x, where x is the identifying value for compound 9 or 11. An activity improvement factor of 1.0 means no difference in activity.

Non-small cell lung.

Central nervous system. Numbers shadowed in different greys mean an increase of antitumor activity (from light to dark grey) for the corresponding compound in relation to compound 2 and the tumor cell line tested.

Table 2.

GI50 in selective cancer cell lines for compounds 9 and 11 in comparison to compound 1

| Average GI50 (nM) in selective Cell Lines |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCL | COLON | CNS | MELANOMA | OVARIAN | BREAST | |||

| Compound | A549 | COLO205 | SF-295 | U251 | SK-MEL-5 | IGROV 1 | OVCAR-8 | MDA-MB-231 |

| 1 | 79 | 63 | 79 | 63 | 63 | 158 | 79 | 166 |

| 9 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 10 | 32 | 50 |

| 11 | 25 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 63 |

In the NCI hollow fiber assay, which measures the preliminary growth inhibition efficacy on a selected panel of 12 tumor cell lines implanted in mice, 9 appeared to be more potent than 1 and 11, with highest total score of 66/96 (as compared to 58/96 for 1); and specifically an intraperitoneal score of 36/48 (34/48 for 1) and a subcutaneous score of 30/48 (24/48 for 1). In contrast, compound 11 shows a total score of 48/96. Based on these data, we decided to evaluate further the toxicity of compound 9 and 11.

In vivo toxicity of compounds 9 and 11

Compound 1 side effects are a major limitation for its use in antitumor therapy. Therefore, we determined experimentally the doses at which compounds 9 and 11 could be safely dosed to mice upon both acute and chronic schedules and using intravenous and intraperitoneal administration routes. As it can be seen in Table 3, the single maximum tolerated dose of 9 is the highest of the mithramycin analogues tested, with maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of 64 mg/Kg for single intravenous injection and 200 mg/Kg for single intraperitoneal injection, yet 11 had similar toxicity as 1 (4 mg/Kg and 6.25 mg/Kg, respectively). When testing repeated doses via intravenous administration every two or three days for 8 cycles (q2dx8 or q3dx8), the MTD for 1 is 0.6 mg/Kg (according to literature data) or 1,5mg/Kg, respectively, while for compound 9 is 12 mg/Kg or 24 mg/Kg, respectively. Thus, it is clearly established that higher doses of compound 9 could be safely administered to mice compared to 1, especially in a repeated dose schedule using intravenous injection. This is the preferred mode of administration, since humans will be dosed intravenously, thus these data can be used as the starting point for a comprehensive toxicology evaluation program.

Table 3.

Maximun tolerated doses of mithramycin compounds

| IV single dose* |

IP single dose* |

IV repeated dose q2dx8* |

IV repeated dose q3dx8* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 mg/kg | 6.25 mg/kg | 0.6 mg/kgb | 1.5 mg/kg |

| 9 | 64 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 12 mg/kg | 24 mg/kg |

| 11 | 4 mg/kg | 6.25 mg/kg | ND | ND |

CD-1 mice received intraperitoneal (IP) or intravenous (IV) single injections or repeated injections of the compound every two days (q2dx8) or three days (q3dx8) for 8 days.

Literature data. ND, not determined.

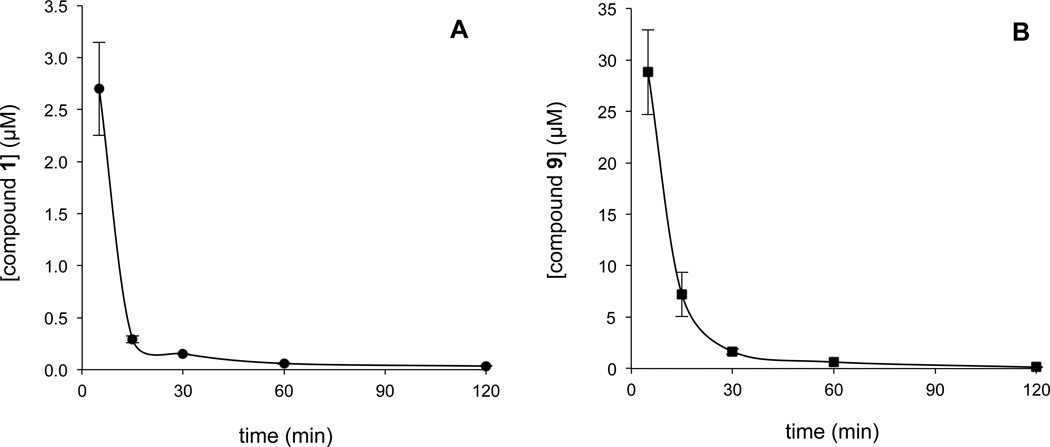

Pharmacokinetic studies of compounds 1 and 9

Plasma levels of compounds 1 and 9 were quantified after intravenous injections at doses of 1 and 18 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 3). The concentration of both compounds in the bloodstream declined exponentially over time, following similar kinetics. Plasma levels of compound 9 were between 5- and 20-fold higher than compound 1, reflecting the different doses injected initially. After 5 min plasma levels of compounds 1 and 9 were approximately 2,7 and 28 μM, respectively. After 30 min, the level of compound 1 was approximately 0,2 μM and that of compound 9 of 1,7 μM. After 120 min, levels of both compounds were below 0,1 μM. According to these data, blood clearance does not seem responsible for the differences in toxicity detected for both compounds.

Figure 3.

Pharmacokinetics profile of compounds 1 and 9. Mice (n=3 per group) were injected intravenously with a single-dose of 1 mg/kg in the case of compound 1 (3A) or 18 mg/kg of compound 9 (3B). Each time point represents mean ± SD of 3 mice.

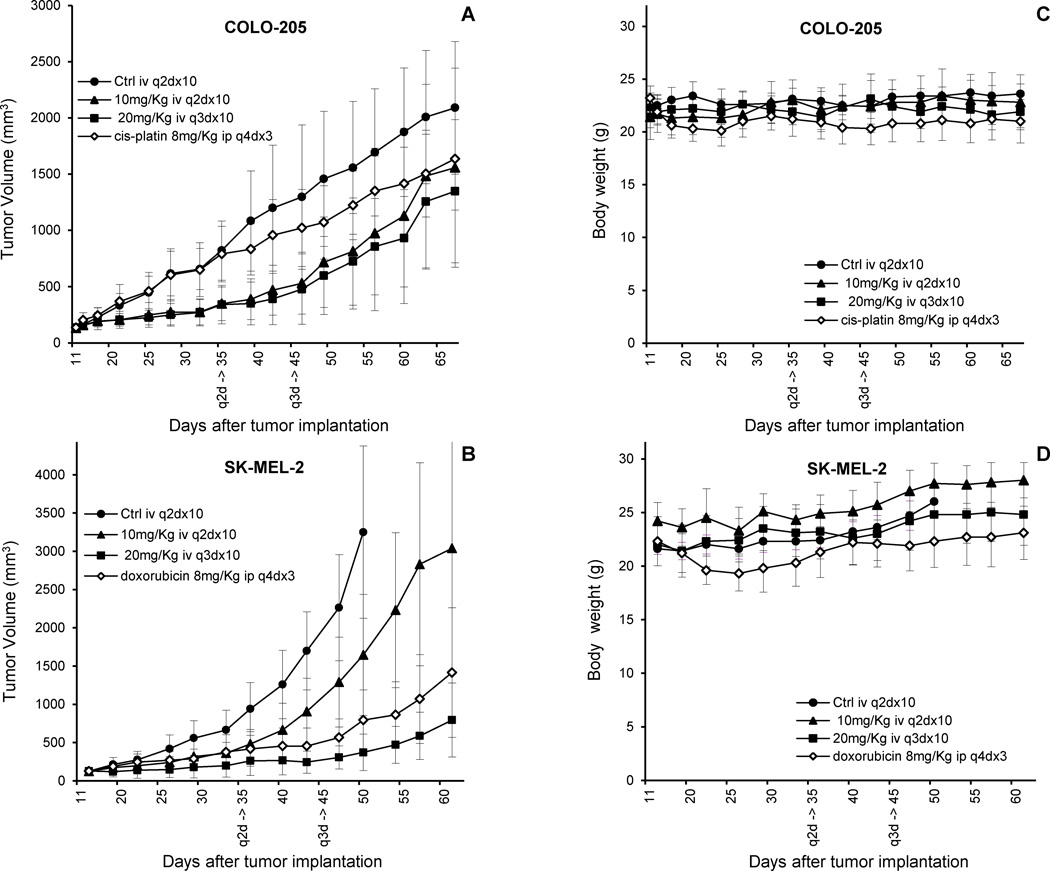

Inhibition of growth of subcutaneous colon and melanoma xenografts by compound 9

Since compound 9 showed the highest antitumor activity in vivo and the lowest toxicity, we decided to examine its antitumor activity in more detail using subcutaneous tumor xenografs of COLO-205 colon cancer cells and SK-MEL-2 melanoma cells, since these are well established tumor models and their GI50 are close to the average value for the NCI-60 screen. Based on the data obtained for the MTD on intravenous repeated dose, mice received intravenous injections q2dx10 at dose 10 mg/Kg, and q3dx10 at dose 20 mg/Kg of compound 9. Total cumulative doses were 100 and 200 mg/Kg. Cis-platin and doxorubicin were used as positive controls. The experiments were terminated long after treatment finished in order observing post-treatment effects, with the exception of mice in control groups that had to be sacrificed due to excessive tumor burden according to ethical guidelines. Treatment with compound 9 reduced notably both colon and melanoma tumors growth at all doses tested (Figure 4A–B). Administration of compound 9 was well tolerated and no signs of toxicity or deaths with any of the schedules of treatment were observed; body weights were not different between mice treated with sterile saline solution or drug even at the highest doses (Figure 4C–D). In the case of COLO-205 colon xenografts, the tumor growth was inhibited by compound 9 at about the same rate using both schedules (every two or every three days), being in both cases more effective than cis-platin Growth of SK-MEL-2 human melanoma xenografts was markedly delayed by treatment with compound 9 at both dosages tested and by doxorubicin. Doxorubicin and compound 9 at a dosage of 20 mg/Kg/injection were comparatively more effective than compound 9 at a dosage of 10 mg/Kg/injection. The effect of the drug during treatment doesn´t cause the tumor to come back aggressively, in the worst case at the same rate as before treatment. It is also of note that efficacy is not compromised by the rapid clearance from bloodstream indicated by pharmacokinetic data. This, together with the better response at highermore spaced doses, can be interpreted as efficacy being dependent not on half-life, but on maximum plasma concentration, which in intravenous administration is obtained just after injection, and therefore is linked to the MTD. Indeed, we measured apoptosis at 48h by flow cytometry in wash-out experiments with drug mice plasma concentrations exposed for the time indicated in the pharmacokinetic curve (see Supporting Information). Short exposures at high concentrations (7μM for 15min) showed significantly higher levels of apoptosis as compared to lower concentrations for longer time (0.2μM for 2h, within the limits of the pharmacokinetic curve). Taken collectively, these data demonstrate that treatment using a spaced schedule (allowing a higher amount of drug) is not worse (but even better) than every other day. The use of a higher amount of drug could translate into a better safety profile while opening the door to an effective but safe treatment.

Figure 4.

Antitumor activity of compound 9 in subcutaneous colon and melanoma tumor xenografts. Mice (eight per group) with subcutaneous colon (A) or melanoma (B) tumors were treated with sterile saline solution (control; closed circles) or the indicated doses of compound 9 given by intravenous injections every two days (q2dx10; closed triangles) or three days (q3dx10; closed squares). Additionally, mice (eight per group) with subcutaneous colon or melanoma tumors were also intraperitoneally injected with 8 mg/kg of cis-platin (A) or doxorubicin (B) every four days (q4dx3; open rhombs). Figure 4A represents the tumor volumes over time with colon cancer COLO-205 cell line. Figure 4C represents evolution of the mice weights with COLO-205 cell line. Figure 4B represents the tumor volumes over time with melanoma SK-MEL-2 cell line. Figure 4D represents evolution of the mice weights with SK-MEL-2 cell line. Each point represents the mean ± SD of eight mice. q2d and q3d indicate end of the treatment.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the potential of combinatorial biosynthesis to expand the chemical space of an antitumor compound like mithramycin, resulting in the generation of new analogues not possible to prepare by current synthetic chemistry technology. A set of these compounds (compounds 5 to 8) differed from 1 in the glycosylation pattern, and showed lower antitumor activity in vitro. This result was in accordance to what it had been previously reported for other glycosylated analogues of 1, which also lacked one or two deoxysugars and showed a decrease in its antitumor activity.30,31 Some exceptions to this rule were compounds that lacking one deoxysugar still contained a d-mycarose residue.30,31 Since compounds 5 to 8 were generated in a mutant defective in d-mycarose biosynthesis, they do not contain this saccharide residue, which fits with their anticipated lower activity. A second set of compounds (compounds 9 to 11) combined modifications in the glycosylation pattern and in the 3-side chain, and showed high antitumor activity, being in average compounds 9 and 11 about 5-fold more active than 10. Compounds 9 and 11 showed similar antitumor activity in vitro, and were also more potent than 1 for some tumor cell lines, although in average they were slightly less potent. These two compounds combined two structural features that had been previously found to improve mithramycin pharmacological behavior: a d-digitoxose residue instead of d-mycarose at the E-position of the trisaccharide chain, and a modified 3-carbon side chain.5,29–31 It has been reported that the oligosaccharide moieties participate in the binding of this family of compounds to DNA, being the sugar E of the trisaccharide sugar chain one of the main interaction points.15–21 Also, modifications at the 3-side chain have revealed to influence the strength of binding to DNA, the capability of inhibiting Sp1 binding to DNA, and the cellular uptake of mithramycins. 5,17–19 Since compounds 9 and 11 are modified exactly at the sugar E and at the 3-side chain, it would be expected to show different properties, as it is the case. In addition, compound 9 showed a better behavior in vivo than 1 and 11 in hollow fiber assays, both on intraperitoneal and subcutaneous implants. Currently, it is unclear the reason for this; a better bioavailability and/or differences in DNA specificity, and consequently differences on inhibition of gene transcription mediated by Sp1 and/or other transcription factors, could account for this better behavior. In this sense, compounds 3 and 4, which only differ from 1 at the 3-side chain, also showed a better activity in vivo in ovarian and prostate tumor xenografs.6,42 On the other hand, pharmacokinetics of compound 9 does not seem the reason for its better behavior in vivo in comparison to the parental compound 1, since studies in mice revealed similar pharmacokinetics for both compounds. In addition, although compound 9 is cleared rapidly from the bloodstream, it´s efficacious in melanoma and colon xenografs, especially at higher, more spaced doses, indicating that maximum concentration, not half-life, is the key for efficacy.

Moreover, compound 9 shows about 32- and between 20- and 16- fold (depending of the pattern of administration) less toxicity than the parental compound 1, for single and repeated treatment in vivo respectively, therefore a better safety profile than the parent natural product, while being in the same range of bioactivity, which hints the possibility of opening the therapeutic window of compounds historically too toxic to provide enough margin of safety to be used in humans. It is known in natural product chemistry that minor structural differences could cause major biological effects. For example doxorubicin and epirubicin show differences in cardiac toxicity, despite the structural differences being just one epimerization in the monosaccharide of the compounds.43 In the case of mithramycins, the 3-side chain seems to have an important role in toxicity. Thus, it has been reported that mithramycin compounds only differing at the 3-side chain show different degrees of toxicity: compound 1 and 4 are less tolerated than compound 3.42 These data are consistent with the fact that compound 9 showed lower toxicity, since it shares the same 3-side chain with compound 3. However, compound 9 was about 2-fold less toxic than compound 3, which suggests that combining a 3-side chain compound 3-like with the presence of d-digitoxe at the E position of the trisaccharide chain has a synergic effect on decreasing its toxicity. It is not clear at this point the reason for this lower toxicity. A possible interpretation is that DNA binding to GC regions by compound 9 shows different specificity and can result in interfering transcription of a different set of genes in healthy and tumor cells. In this sense, it has been reported that there are subtle differences in the GC-rich sequences specifically recognized by different analogues of the aureolic acid antibiotics, which either differed in the 3-side chain, the saccharide profile or both.19 Also, in vivo studies on the closely related compounds 3 and 4 have shown that the more toxic analogue compound 4 causes higher downregulation in a larger number of genes and recovery takes longer than in the less toxic analog compound 3, in prostate cancer cells.42 Recent evidence shows better potency and improved selectivity of compound 9 over 1 in sarcoma cell lines overexpressing the EWS-FLI1 transcription factor. Compound 9 compared to 1 inhibits more effectively luciferase activity driven by NRB01 (a downstream target of EWS-FLI1) as opposed to a non-specific promoter.44 These observations may change depending on the histology under study. Ongoing research to clarify the reasons for the lower toxicity will be published in due course.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Strains, culture conditions, and DNA manipulation

Streptomyces argillaceus M7C137 and S. argillaceus M3W129 were used as hosts for plasmid expression and production. For sporulation they were grown for 7 days at 30° C on agar plates containing medium A45 supplemented with 25 µg/ml of thiostrepton. For protoplasts regeneration, the organisms were grown on R5 solid medium plates.46 Liquid and solid media for production and isolation of mithramycin derivatives was modified R5 medium (R5A).45 DNA manipulations were performed according to standard techniques for E. coli 47 and Streptomyces.46

Generation of mithramycin derivatives

Three sugar plasmids were used: pFL845, pMP3*BII and pKOL. pFL845 directs the biosynthesis of d-amicetose and d-olivose.39 pMP3*BII codes for the biosynthesis of d-digitoxose.40 Plasmid pKOL was constructed from plasmid pLN248 by digesting out the oleU 4-ketoreductase gene using NheI and SpeI restriction enzymes and religation of the compatible ends to generate pKOL (see also Scheme 1). All the genes in the plasmids are under control of one or two strong ermEp* promoters. Plasmids pFL845, and pMP3*BII and pKOL were introduced into Streptomyces argillaceus M7C1 and S. argillaceus M3W1 respectively, by protoplast transformation according to standard procedures for Streptomyces.46 Transformants were selected with thiostrepton (50 μg/mL final concentration). A thiostrepton-resistant colony from each was selected for further characterization (strains S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845, S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII and S. argillaceus M3W1-pKOL, respectively). HPLC analyses were performed as previously described.32,49

Purification of new compounds

For purification of compounds produced by strain S. argillaceus M7C1-pFL845, 100 plates of R5A medium supplemented with thiostrepton were uniformly inoculated and incubated at 30°C during 7 days. Agar cultures were removed from the plates and were extracted three times with ethyl acetate.50 The organic extracts were evaporated under vacuum and finally dissolved in 5 ml of a mixture of DMSO and methanol (50:50). The first purification step was done by chromatography in an XTerra PrepRP18 column (19 × 300 mm, Waters) with acetonitrile and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water as solvents. A linear gradient from 30% to 100% acetonitrile in 7 min followed by a 3 min isocratic hold with 100% acetonitrile was used, at a flow rate of 15 ml/min. 1 min fractions were taken and analysed by HPLC. Those containing the desired compounds were evaporated and dissolved in a small volume of the mixture of DMSO and methanol. Further purifications were performed in isocratic conditions with a Symmetry C18 column (7.8 × 300 mm, Waters), using mixtures of acetonitrile and 0.05% TFA in water optimized for each peak, at a flow rate of 7 ml/min. Peaks of interest were collected on 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The solutions obtained were partially evaporated under vacuum to reduce the organic solvent concentration and then applied to a solid phase extraction cartridge (Sep-Pak C18, Waters), washed with water to remove salts and eluted with methanol. The isolated compounds were finally dissolved in tert-butanol and lyophilized.

An alternative method was carried out for purification of the novel derivatives produced by strain S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII. One hundred and fifty agar plates of R5A medium supplemented with thiostrepton were uniformly inoculated and after 10 days of incubation at 30°C, cultures were extracted six times with ethyl acetate and extracts were evaporated under vacuum. The dry extract was dissolved in 50 ml of distilled water and solid-phase extracted (SepPak Vac C18, Waters). A linear gradient of methanol and water (0–100% methanol during 60 min at 10 ml min−1) was applied for elution of the retained material. Fractions obtained were analyzed by HPLC and those containing the desired compounds were mixed and dried under vacuum. This dry extract, previously dissolved in 10 ml of methanol, was chromatographed in a XBridge™ Prep C18 column (5 μm, 30 × 150 mm, Waters) using a mixture of MeCN and 0.1% TFA in water (35:65) as mobile phase, at flow of 20 ml min−1. All compounds collected were repurified using the same column and mixture of solvents. Fractions obtained were collected on 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and after purification, samples were diluted fourfold with water to be desalted and concentrated by solid-phase extraction, being finally lyophilized, and their purity (≥ 95%) was checked by HPLC.

The isolated amounts for the different compounds were as follows: 2.5 mg of 5; 22.2 mg of 6; 3.9 mg of 7; 3.8 mg of 8; 52.1 mg of 9; 18.8 mg of 10; and 38.0 mg of 11.

Chemical characterization of new mithramycin derivatives

The structures of the new mithramycin analogues were elucidated by NMR spectroscopy, employing 1D 1H, 13C, 2D homonuclear 1H COSY/TOCSY/NOESY and heteronuclear 1H-13C HSQC/HMBC experiments. NMR data were recorded in acetone-d6 at 298 K using a Bruker Avance Ultrashield Plus 600 spectrometer (600 MHz for 1H, 150 MHz for 13C experiments). Typical parameters for 2D experiments were: COSY/TOCSY, 256 and 2048 points in F1 and F2, respectively, 48 transients each; HSQC, 256 and 2048 points in F1 and F2, respectively, 64 transients each; HMBC, 512 and 2048 points in F1 and F2, respectively, 64 transients each NMR experiments were processed using the program Topspin 1.3 (Bruker GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Antitumor assays

In vitro cell growth inhibition assay

The antitumor activity of the mithramycin derivatives was tested preliminary against a panel of three tumor cell lines: COLO-205 (colon), A549 (non-small cell lung) and BXCP3 (pancreas). Cell viability was determined using the MTT colorimetric assay.51 Cells were plated in 96-well plates and incubated with vehicle or compounds for 72 h. Each treatment was performed in triplicate and experiments were repeated at least three times.

The NCI-60 anticancer drug screen and hollow fiber assay

the methodologies have been described in details elsewhere (http://www.dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html, http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/acute_tox.html, http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/hfa.html). NCI-60 screening experiments were conducted using five concentrations between 10−9 to 10−5 M of each compound. To compare the anti-proliferative activities between 1 and 9–11, averaged GI50 cross different cell lines were calculated from duplicated screening experiments performed for 9–11 in the present study, and two historically experiments for 1.

Preliminary in vivo efficacy was determined in hollow fiber assay using 12 tumor cell lines: COLO205, SW-620 (colon), LOX IMV1 and UACC-62 and MDA-MB-435 (melanoma), MDA-MB-231 (breast), NCI-H23 and NCI-H522 (non-small cell lung), OVCAR-3, OVCAR-5 (ovarian), SF-295 and U251 (CNS). Mice bearing different cell lines were treated with each compound administered daily by intraperitoneal injection at dose levels calculated based on MTD for four days.

Assays of toxicity

Healthy CD-1 mice (n=4) provided by the University of Oviedo Specific Pathogen Free Animal Facility were treated with single tail intravenous injections of compounds 9, 11 and 1, using saline solution as vehicle for solubilization of the compounds. Body weight, deaths, changes in behaviour, motility, eating and drinking habits, and any other sign of local or systemic toxicity were recorded daily. Maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is the maximum dose that not cause apparent symptoms nor significant mortality (one mice per group allowed) in the 15 days following administration. Compound 1 tolerated dose is 2 mg/kg, and dose escalation for other derivatives started at 4 mg/kg and doubling dose using groups of four mice (two males and two females) in order to determine the MTD. Alternatively, acute toxicity was determined by measuring MTD in a single intraperitoneal injection of each compound at different concentrations using NCI protocols. Repeated dose MTD was determined only for intravenous administration of different dose levels (10mg/kg and 20mg/kg) at different schedules (each 2 days and each 3 days respectively). Mice were monitored during the course of the treatment and 7 days afterwards.

Pharmacokinetics studies

Plasma pharmacokinetics of compounds 1 and 9 was evaluated in healthy female CD-1 mice following single-dose intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg and 18 mg/kg, respectively. Plasma samples were collected at 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after injection using 3 animals per time point. Samples were 5-fold diluted with methanol and centrifuged to eliminate any insoluble precipitate. Concentration of compounds 1 and 9 in the supernatant was determine by LC-MS analysis as described elsewhere.42

In vivo evaluation of antitumor activity

To assess tumor growth inhibition, groups of athymic nu/nu mice (n=8) provided by Harlan were implanted subcutaneous tumors and were treated with compounds or vehicle. Drugs were prepared in sterile saline solution and given by intravenous injections q3dx10 and q2dx10. Tumor size was measured with a caliper twice a week. Mice weight and other toxicity symptoms were recorded twice weekly. Animals were sacrificed if needed according to ethical regulations; otherwise the experiment was terminated two months since the implantation in order to observe post-treatment effects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA091901 to J.R.) and of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (BIO2005-04115 and BIO2008-00269 to C.M.; and PET2005-0401 to C.M. and F.M.). M.P. was the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. L.E.N. was the recipient of Torres-Quevedo program funding (PTQ04-3-0487) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. S. Eric Nybo was partially supported by a graduate fellowship from the University of Kentucky graduate school.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- cox2

cyclooxygenase-2

- ESFTs

Ewing sarcoma family of tumors

- EWS-FLI1

Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 and Friend leukemia virus integration 1

- GI50

50% growth inhibition

- IP

intraperitoneal

- IV

intravenous

- MDR-1

multidrug resistant gene 1

- NDP

nucleoside diphosphate

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- p21cip1/waf1

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1

- p53

protein 53

- q2dx10

a single dose every 2 days times 10

- q3dx10

a single dose every three days times 10

- R5-A

modified R5 medium

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Sp1

Specificity Protein 1

- STAT3

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3

- TF

Transcription Factor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-beta

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE: HPLC-chromatograms of S. argillaceus compared to S. argillaceus (pKOL), S. argillaceus M3W1 compared to S. argillaceus M3W1-pKOL, S. argillaceus M3C1-pFL845 and S. argillaceus M3W1-pMP3*BII. NMR data and spectra of novel compounds. Apoptosis data for wash-out experiments. Abbreviations used. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Darnell JE., Jr. Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:740–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain D, Frank DA. Targeting the cytoplasmic and nuclear functions of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 for cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:5665–5669. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page BD, Ball DP, Gunning PT. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 inhibitors: a patent review. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2011;21:65–83. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.539205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilczynski J, Duechler M, Czyz M. Targeting NF-κB and HIF-1 pathways for the treatment of cancer: part I. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 2011;59:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albertini V, Jain A, Vignati S, Napoli S, Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Nur-e-Alam M, Bergant J, Bertoni F, Carbone G, Rohr J, Catapano CV. Novel GC-rich DNA-binding compound produced by a genetically engineered mutant of the mithramycin producer Streptomyces argillaceus exhibits improved transcriptional repressor activity: implications for cancer therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1721–1734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Previdi S, Malek A, Albertini V, Riva C, Capella C, Broggini M, Carbone GM, Rohr J, Catapano CV. Inhibition of Sp1-dependent transcription and antitumor activity of the new aureolic acid analogues mithramycin SDK and SK in human ovarian cancer xenografts. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010;118:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safe S, Abdelrahim M. Sp transcription factor family and its role in cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:2438–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman J, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Zaman K, Ryu H, Conforto A, Ratan RR. Sequence-selective DNA binding drugs mithramycin A and chromomycin A3 are potent inhibitors of neuronal apoptosis induced by oxidative stress and DNA damage in cortical neurons. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia Z, Zhang J, Wei D, Wang L, Yuan P, Le X, Li Q, Yao J, Xie K. Molecular basis of the synergistic antiangiogenic activity of bevacizumab and mithramycin A. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4878–4885. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia Z, Gao Y, Wang L, Li Q, Zhang J, Le X, Wei D, Yao JC, Chang DZ, Huang S, Xie K. Treatment with Combination of Mithramycin A and Tolfenamic Acid Promotes degradation of Sp1 Protein and Synergistic Antitumor Activity in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1111–1119. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fajardo OA, Thompson, Parapuram SK, Liu S, Leask A. Mithramycin reduces expression of fibro-proliferative mRNAs in human gingival fibroblasts. Cell Prolif. 2011;44:166–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seznec J, Silkenstedt B, Naumann U. Therapeutic effects of the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin A in glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2011;101:365–377. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grohar PJ, Woldemichael GM, Griffin LB, Mendoza A, Chen Q-R, Yeung C, Currier DG, Davis S, Khanna C, Khan J, McMahon JB, Helman LJ. Identification of an Inhibitor of the EWS-FLI1 Oncogenic Transcription Factor by High-Throughput Screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr156. first published online June 8, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sastry M, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the mithramycin dimmer–DNA complex. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6588–6604. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sastry M, Fiala R, Patel DJ. Solution structure of mithramycin dimers bound to partially overlapping sites on DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;251:674–689. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barcelo F, Scotta C, Ortiz-Lombardía M, Méndez C, Salas JA, Portugal J. Entropically-driven binding of mithramycin in the minor groove of C/G-rich DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2215–2226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barcelo F, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Martorell M, Oliver M, Mendez C, Salas JA, Portugal J. DNA Binding Characteristics of Mithramycin and Chromomycin Analogues Obtained by Combinatorial Biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2010;49 doi: 10.1021/bi101398s. 10543–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansilla S, Garcia-Ferrer I, Mendez C, Salas JA, Portugal J. Differential inhibition of restriction enzyme cleavage by chromophore-modified analogues of the antitumour antibiotics mithramycin and chromomycin reveals structure–activity relationships. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:1418–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan P, Wang L, Wei D, Zhang J, Jia Z, Li Q, Le X, Wang H, Yao J, Xie K. Therapeutic inhibition of Sp1 expression in growing tumors by mithramycin A correlates directly with potent antiangiogenic effects on human pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:2682–2690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell VW, Davin D, Thomas S, Jones D, Roesel J, Tran-Patterson R, Mayfield CA, Rodu B, Miller DM, Hiramoto RA. The G-C specific DNA binding drug, mithramycin, selectively inhibits transcription of the c-myc and c-ha-ras genes in regenerating liver. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1994;307:167–172. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TJ, Jung EM, Lee JT, Kim S, Park JW, Choi KS, Kwon TK. Mithramycin a sensitizes cancer cells to trail-mediated apoptosis by down-regulation of XIAP gene promoter through Sp1 sites. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2737–2746. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koutsodontis G, Kardassis D. Inhibition of p53-mediated transcriptional responses by mithramycin A. Oncogene. 2004;23:9190–9200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tagashira M, Kitagawa T, Isonishi S, Okamoto A, Ochiai K, Ohtake Y. Mithramycin represses MDR1 gene expression in vitro, modulating multidrug resistance. Biol. Pharmac. Bull. 2000;23:926–929. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sleiman SF, Langley BC, Basso M, Berlin J, Xia L, Payappilly JB, Kharel MK, Guo H, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Mahishi L, Ahuja P, MacLellan WR, Geschwind DH, Coppola G, Rohr J, Ratan RR. Mithramycin Is a Gene-Selective Sp1 Inhibitor That Identifies a Biological Intersection between Cancer and Neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:6858–6870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0710-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohlert SE, Künzel E, Machinek R, Méndez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. The structure of mithramycin reinvestigated. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:119–121. doi: 10.1021/np980355k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombó F, Menéndez N, Salas JA, Méndez C. The aureolic acid family of antitumor compounds: structure, mode of action, biosynthesis, and novel derivatives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;73:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombó F, Künzel E, Prado L, Braña AF, Bindseil KU, Frevert J, Bearden D, Méndez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. The Novel Hybrid Antitumor Compound Premithramycinone H Provides Indirect Evidence for a Tricyclic Intermediate of the Biosynthesis of the Aureolic Acid Antibiotic Mithramycin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2000;39:796–799. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000218)39:4<796::aid-anie796>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remsing LL, González AM, Nur-e-Alam M, Fernández-Lozano MJ, Braña AF, Rix U, Oliveira MA, Méndez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. Mithramycin SK, a novel antitumor drug with improved therapeutic index, mithramycin SA, and demycarosyl-mithramycin SK: three new products generated in the mithramycin producer Streptomyces argillaceus through combinatorial biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5745–5753. doi: 10.1021/ja034162h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baig I, Perez M, Braña AF, Gomathinayagam R, Damodaran C, Salas JA, Méndez C, Rohr J. Mithramycin analogues generated by combinatorial biosynthesis show improved bioactivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:199–207. doi: 10.1021/np0705763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez M, Baig I, Braña AF, Salas JA, Rohr J, Méndez C. Generation of new derivatives of the antitumor antibiotic mithramycin by altering the glycosylation pattern through combinatorial biosynthesis. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2295–2304. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García B, González-Sabín J, Menéndez N, Braña AF, Núñez LE, Morís F, Salas JA, Méndez C. The chromomycin CmmA acetyltransferase: a membrane-bound enzyme as a tool for increasing structural diversity of the antitumour mithramycin. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011;4:226–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remsing LL, Bahadori HR, Carbone GM, McGuffie EM, Catapano CV, Rohr J. Inhibition of c-src transcription by mithramycin: structure-activity relationships of biosynthetically produced mithramycin analogues using the c-src promoter as target. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8313–8324. doi: 10.1021/bi034091z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mir MA, Majee S, Das S, Dasgupta D. Association of chromatin with anticancer antibiotics, mithramycin and chromomycin A3. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:2791–2801. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majee S, Sen R, Guha S, Bhattacharyya D, Dasgupta D. Differential interactions of the Mg2+ complexes of chromomycin A3 and mithramycin with poly(dG-dC) × poly(dC-dG) and poly(dG) × poly(dC) Biochemistry. 1997;36:2291–2299. doi: 10.1021/bi9613281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lombó F, Olano C, Salas JA, Méndez C. Sugar biosynthesis and modification. Methods Enzymol. 2009;458:277–307. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González A, Remsing LL, Lombó F, Fernández MJ, Prado L, Braña AF, Künzel E, Rohr J, Méndez C, Salas JA. The mtmVUC genes of the mithramycin gene cluster in Streptomyces argillaceus are involved in the biosynthesis of the sugar moieties. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2001;264:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s004380000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remsing LL, Garcia-Bernardo J, Gonzalez A, Künzel E, Rix U, Braña AF, Bearden DW, Méndez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. Ketopremithramycins and ketomithramycins, four new aureolic acid-type compounds obtained upon inactivation of two genes involved in the biosynthesis of the deoxysugar moieties of the antitumor drug mithramycin by Streptomyces argillaceus, reveal novel insights into post-PKS tailoring steps of the mithramycin biosynthetic pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1606–1614. doi: 10.1021/ja0105156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pérez M, Lombó F, Zhu L, Gibson M, Braña AF, Rohr J, Salas JA, Méndez C. Combining sugar biosynthesis genes for the generation of L- and D-amicetose and formation of two novel antitumor tetracenomycins. Chem. Commun. 2005:1604–1606. doi: 10.1039/b417815g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pérez M, Lombó F, Baig I, Braña AF, Rohr J, Salas JA, Méndez C. Combinatorial biosynthesis of antitumor deoxysugar pathways in Streptomyces griseus: Reconstitution of "unnatural natural gene clusters" for the biosynthesis of four 2,6-D-dideoxyhexoses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:6644–6652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01266-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyd MR, Paull KD. Some Practical Considerations and Applications of the National Cancer Institute In Vitro Anticancer Drug Discovery Screen. Drug Develop. Res. 1995;34:91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malek A, Núñez LE, Magistri M, Brambilla L, Jovic S, Carbone GM, Morís F, Catapano CV. Modulation of the activity of Sp transcription factors by mithramycin analogues as a new strategy for treatment of metastatic prostate cáncer. PLoS ONE. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035130. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torti FM, Bristow MM, Lum BL, Carter SK, Howes AE, Aston DA, Brown BW, Jr., Hannigan JF, Jr., Meyers FJ, Mitchell EP, Billingham ME. Cardiotoxicity of Epirubicin and Doxorubicin: Assessment by Endomyocardial Biopsy. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3722–3727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gebregiorgis M, Woldemichael G, He M, Kang MH, Núñez LE, Morís F, Smith MA, Helman LJ, Grohar PJ. Identification of mithramycin analogues with increased potency and more selective inhibition of EWS-FLI1 for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma. Poster at AACR Annual meeting; March 31–April 4, 2012; Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernández E, Weibbach U, Sánchez Reillo C, Braña AF, Méndez C, Rohr J, Salas JA. Identification of two genes from Streptomyces argillaceus encoding two glycosyltransferases involved in the transfer of a disaccharide during the biosynthesis of the antitumor drug mithramycin. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4929–4937. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4929-4937.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces genetics. Norwich, UK: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez L, Aguirrezabalaga I, Allende N, Braña AF, Méndez C, Salas JA. Engineering deoxysugar biosynthetic pathways from antibiotic-producing microorganisms. A tool to produce novel glycosylated bioactive compounds. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lombó F, Abdelfattah MS, Braña AF, Salas JA, Rohr J, Méndez C. Elucidation of oxygenation steps during oviedomycin biosynthesis and generation of derivatives with increased antitumor activity. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:296–303. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menéndez N, Mohammad N, Braña AF, Rohr J, Salas JA, Méndez C. Biosynthesis of the antitumor chromomycin A3 in Streptomyces griseus: analysis of the gene cluster and rational design of novel chromomycin analogues. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assay. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.