Abstract

Peroxiredoxin 2 (Prx2), the third most abundant cytoplasmic protein in red blood cells (RBCs), is involved in the defense against oxidative stress. Although much is known about Prx2 in healthy RBCs, its role in pathological RBCs remains largely unexplored. Here, we show that the expression and net content of Prx2 are markedly increased in RBCs from two mouse models of β-thalassemia (β-thal; Hbbth/th and Hbbth3/+ strains). We also demonstrate that the increased expression of Prx2 correlates with the severity of the disease and that the amount of Prx2 bound to the membrane is markedly reduced in β-thal mouse RBCs. To explore the impact of oxidative stress on Prx2 membrane association, we examined Prx2 dimerization and membrane translocation in murine RBCs exposed to various oxidants (phenylhydrazine, PHZ; diamide; H2O2). PHZ-treated RBCs, which mimic the membrane damage in β-thal RBCs, exhibited a kinetic correlation among Prx2 membrane displacement, intracellular methemoglobin levels, and hemichrome membrane association, suggesting the possible masking of Prx2 docking sites by membrane-bound hemichromes, providing a possible mechanism for the accumulation of oxidized/dimerized Prx2 in the cytoplasm and the increased membrane damage in β-thal RBCs. Thus, reduced access of Prx2 to the membrane in β-thal RBCs represents a new factor that could contribute to the oxidative damage characterizing the pathology.

Keywords: Oxidative damage, Diamide, Phenylhydrazine, Thalassemias, Erythrocytes, Hydrogen peroxide, Free radicals

Peroxiredoxins are ubiquitous proteins involved at least in part in the defense against oxidative stress through their ability to reduce and detoxify a vast range of organic peroxides, H2O2, and peroxynitrite [1–3]. In red cells, peroxiredoxin-2 (Prx2)1 is the third most abundant cytoplasmic protein and a typical 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin. Erythrocyte Prx2 (formerly termed calpromotin) was initially characterized as a membrane-associated protein whose reversible binding to the membrane was linked to regulation of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel (Gardos channel) via a still unknown mechanism [1,4–11]. In a mouse model of sickle cell disease, interaction of Prx2 with the membrane was further shown to be modulated during hypoxia-induced acute sickle cell-related vaso-occlusive crisis [12]; however, a function of this reversible association was not established. Recently Rocha et al. reported specific binding of Prx2 in patients with hereditary spherocytosis [9]. In Prx2 knockout mice, elimination of erythrocyte Prx2 has, moreover, been demonstrated to induce a hemolytic anemia associated with signs of red cell oxidative damage [13].

β-Thalassemia is a common inherited red cell disorder caused by the reduced or absent synthesis of the β chain of hemoglobin. The resulting imbalance between α and β chains leads to precipitation of α-globin chains on the membrane, which induces membrane damage and a shortening of erythrocyte life span [14–18]. Red cells from β-thalassemia intermedia patients show membrane clusters of hemichromes and band 3, presumably as a consequence of oxidative injury [14–20]. Immunoglobulins and complement components localize on the membrane surface over these clusters, mediating the removal of the damaged erythrocytes by macrophages. Membrane lipid peroxidation, loss of phospholipid asymmetry, and externalization of phosphatidylserine have been also documented in β-thalassemic erythrocytes [16,18,21]. Importantly, mouse models of β-thalassemia show most of the pathologic features of their human counterparts.

In our studies of Prx2 behavior in β-thalassemia, we have focused on two mouse models of the disease. In the first model, spontaneous deletion of the b1 gene (Hbbth/th) results in the absence of β-major globin synthesis that is accompanied by a partial compensatory increase in β-minor globin chain synthesis. The derived erythrocytes are characterized by a net ~25% reduction in β chain expression, resulting in a mild β-thalassemia. In the second model, heterozygous deletion of both b1 and b2 loci (Hbbth3/+), without any compensatory production of adult β-globin chains, is seen to result in an ~50% decrease in β-globin synthesis [20,22], leading to a more severe form of the disease. Previous studies of these two β-thalassemic mouse models have suggested that Hbbth/th most closely resembles the mild phenotype of human β-thalassemia intermedia, whereas the anemia, splenomegaly, and bone abnormalities of Hbbth3/+ are more similar to the pathologic symptoms of severe human β-thalassemic heterozygotes. In both models as well as in human cases of β-thalassemia, oxidative damage to the membrane is believed to cause many of the pathologic features of the disease.

Here, we show that Prx2 expression and content were higher in red cells from β-thalassemic mouse models than in wild-type mice but the amount of Prx2 associated with the membrane was markedly reduced. We showed that Prx2 responds differently to various oxidants (phenylhydrazine, PHZ; diamide; and H2O2) and partitions abnormally between the membrane and the cytosol in response to different oxidative stresses. The translocation to the membrane of either native Prx2 or Prx2 from oxidant-treated red cells was markedly reduced when the red cell membranes were treated with PHZ to generate β-thalassemic-like red cell membrane damage. The intercorrelations among Prx2 membrane binding, methemoglobin (MetHb) formation, and hemichrome membrane binding together with the accumulation of oxidized/dimerized Prx2 in the cytoplasm might affect Prx2 antioxidant function similarly on β-thal and PHZ-treated membrane proteins and represent a new factor contributing to the oxidative damage characterizing β-thalassemia.

Material and methods

Drugs and chemicals

NaCl, KCl, Na2HPO4, Na3VO4, KH2PO4, MgCl2, NH4HCO3, Mops, Tris, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), choline chloride, benzamidine, β-mercaptoethanol, glycine, bromphenol blue, trypsin, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and glycerol were obtained by Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); urea, thiourea, dithiotreithol (DTT), iodoacetamide, tri-n-butylphosphate, tri-fluoroacetic acid, and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid were from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland); Chaps and low-melting agarose were from USB (Cleveland, OH, USA); acetone, methanol, and acetonitrile were from Baker (Deventer, The Netherlands); protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were from Roche (Basel, Switzerland); Immobiline DryStrip 7-cm pH 4–7 gels, IPG buffer pH 3–10, Triton X-100, ECL-Plus, and Percoll were purchased from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, UK); and 40% acrylamide: bis solution, 37.5:1, was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA).

Mouse strains and design of the study

C57B6/2 J mice (wild-type controls, WT) and two mouse strains that underexpress β-globin chains, the Hbbth/th mouse and the Hbbth3/+ mouse, were employed as models of β-thalassemia [20,23]. Male and female mice of 2 to 6 months age (20–25 g body wt) were used. Blood was collected by retro-orbital venipuncture in anesthetized mice using heparinized microcapillary tubes.

Measurements of hematological parameters, methemoglobin levels, and hemichromes bound to the membrane

Blood was centrifuged at 2500 g at 4 °C to remove plasma, passed through cotton to eliminate white cells, and washed three times with choline wash solution (180 mM choline, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris–Mops, pH 7.4 at 4 °C, 320–340 mOsm). Hematological parameters were evaluated on a Bayer Technicon Analyser ADVIA. Hematocrit and hemoglobin were manually determined [20,23,24]. Red cell MetHb levels were determined as described by Kohn et al. [25]. Measurement of methemoglobin concentration was based on the absorbance of methemoglobin at 630 nm, which is characterized by εmM 630 = 4.4 mM–1 cm–1 [26]. Addition of cyanide eliminates the contribution of methemoglobin to the absorbance at 630 nm. The absorbance in the absence of cyanide minus that in the presence of cyanide is a measure of the conversion of methemoglobin in the sample to cyanomethemoglobin [25,26].

Hemichromes bound to the membrane were measured as previously described by Ayi et al. [27].

Molecular analysis of mouse spleens and bone marrow

Total RNA was isolated from spleen and bone marrow from wild-type and both of the β-thalassemic mouse models (n = 4 from each strain) using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After measurement of RNA yield and quality by NanoDrop machine (Celbio), cDNA was synthesized by random hexamers with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), according to the protocols supplied by Bio-Rad. Two micrograms of total RNA in 20 μl was used in each reaction. QRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the Applied Biosystems Model 7900HT sequence detection system, according to the protocols supplied by Applied Biosystems. Primers were designed with the Primer Express 2.1 program (Applied Biosystems). All of the primers were designed in two different exons to avoid the amplification of genomic DNA. All QRT-PCRs were performed in duplicate. A portion (1.5 μl) of the ss-cDNA synthesis reaction was used in each 25-μl reaction. The α-globin gene (Hba) mRNA was used to normalize the mRNA concentration. The primer sequences for the tested genes were the following: mPrdx2 forward, 5′-CGCCTAGTCCAGGCCTTTC-3′; mPrdx2 reverse, 5′-GATGGTGTCACTGCCGGG-3′; mHba forward, 5′-TGCGTGTGGATCCCGTC-3′; mHba reverse, 5′-TGAAATCGGCAGGGTGGT-3′.

The relative gene expressions were calculated using the 2–ΔCt method. The ΔCt was calculated using the differences in the mean Ct between the genes and their internal controls [28].

Treatment of red cells with oxidative agents

Red cells from wild-type mice underwent treatment with three different oxidative agents, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 75, 100 μM), diamide (2 mM), and PHZ (20, 50, 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000 μM), in vitro, as we previously reported [15,29]. The concentration of H2O2 was adapted so that the ratio H2O2/red cells would be similar to the conditions previously described by Low et al. [30]. Whenever indicated, red cells were pretreated with sodium azide (NaN3; 100 mM) to inhibit catalase before exposure to oxidative agents [1,2].

Crossing experiments

To evaluate whether Prx2 from untreated red cells and from red cells exposed to oxidative stress possesses different degrees of affinity for native or oxidized membrane, we incubated native and oxidatively treated red cell ghosts with cytoplasmic fractions of untreated and oxidatively treated red cells as we previously reported, with minor modifications [31]. We also treated isolated red cell ghosts with either 2 mM diamide or 50 μM phenylhydrazine incubated 10 min at 4 °C; the treated isolated ghosts were then washed three times in 5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8, 1 mM DTT in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at 13,000 g, at 4 °C for 10 min.

Immunoblot analysis of mouse red cell membranes

Red cells were analyzed either in unfractionated form or after separation on a discontinuous Percoll density gradient that yielded fraction 1 (F1) corresponding to a density of <1.074 (containing reticulocytes) and fraction 2 (F2) corresponding to a density of >1.092 (containing the densest and most of the oldest red cells) [29].

Packed red cells were lysed in ice-cold phosphate lysis buffer (LB; 5 mM Na2HPO4, pH 8.0, containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, 3 mM benzamidine final concentration, 1 mM Na3VO4 final concentration) in the presence of 100 mM NEM, to avoid possible artifacts related to Prx2 oxidation during cell preparation as previously reported by Low et al. [30], and centrifuged 10 min at 4 °C at 12,000 g [32]. Red cell ghosts were washed several times in LB before analysis by SDS–PAGE. Proteins from ghosts and the cytosol fraction were solubilized in nonreducing sample buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, few grains of bromphenol blue) and analyzed by one-dimensional SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were either stained with colloidal Coomassie or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody (clone LF-PA0007; LabFrontier, Korea), anti-peroxiredoxin-SO3 antibody (clone LF-PA0004; LabFrontier), and anti-band 3 antibody (clone BIII-136; Sigma–Aldrich). Blots were developed using chemiluminescence reagents (ECL; Amersham). Densitometric analysis of band intensities was carried out using Quantity One analysis software (Bio-Rad). To better compare Prx2 expression in β-thalassemic mouse red cells with WT mouse erythrocytes the quantification of the densitometry of cytosol immunoblot data was expressed on a per-cell basis. In addition, we evaluated the expression of Prx2 in total red cell lysates obtained as previously described by De Franceschi et al. [33]. Cells (0.8×106 for each condition) were used for immunoblot analysis. Whenever indicated, membrane skeletal and soluble fractions were prepared as previously described by Bordin et al. and analyzed as above [34]. Briefly, ghosts were extracted at 4 °C after 1 h incubation in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, 3 mM benzamidine final concentration, 1 mM Na3VO4 final concentration) and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 40 min at 4 °C. Supernatant, corresponding to the Triton-soluble fraction, and pellet, corresponding to the Triton-insoluble fraction (membrane skeleton), were analyzed by one-dimensional electrophoresis as described above.

Immunofluorescence assay

Packed and washed red cells were resuspended in 0.5% acrolein prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 2.68 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4) and allowed to fix for 5 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were rinsed three times in rinsing buffer (PBS, 0.1 M glycine, 0.1% sodium azide) and permeabilized in rinsing buffer plus 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. After three additional washes, fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated in rinsing buffer at room temperature for 30 min to ensure complete neutralization of unreacted aldehydes. All nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation for 60 min to 12 h in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.05 mM w/v glycine, 0.2% w/v fish skin gelatin, 0.1% w/v sodium azide). Fixed and permeabilized RBCs were immunostained using antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Cells were incubated at 2% Hct with the primary antibody (anti-Prx2; LabFrontier) for 45 min at room temperature with gentle shaking and rinsed three times in blocking buffer. After centrifugation at 500 g, labeled cells were incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG; Invitrogen, USA) under the same conditions described for primary antibodies. After being labeled, the resuspended RBCs were allowed to attach to coverslips coated with polylysine, and the coverslips were mounted using a water solution of 50% v/v glycerol. Samples were imaged using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 60×, 1.2 numerical aperture water immersion lens.

Protein identification

MALDI-TOF analysis

Mass spectrometric analysis was performed using a Tofspec SE (Micromass, Manchester, UK) equipped with a delayed extraction unit. Peptide desorption was achieved using a laser wavelength of 337 nm, and mass spectra were obtained in the reflectron mode in the mass range 800–4000 Da. Peptide solutions were prepared with an equal volume of saturated α-cyano-4hydroxycinnamic acid solution containing 40% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (v/v). External calibration was performed using fragment ions from standard peptides, adrenocorticotropic hormone 18-39, and angiotensin I. Each mass spectrum was generated by accumulating data from 100–120 laser pulses. Database searches of peptide masses were performed using the search program Mascot, Peptide Mass Fingerprint (available at http://www.matrixscience.com). The following search criteria were used: taxa Rodentia—Mus musculus, protein molecular mass range from 10 to 300 kDa, trypsin digest, monoisotopic peptide masses, one missed cleavage by trypsin, and a mass deviation of 100 ppm allowed in the NCBI database searches [12,35,36].

Automated LC–MS/MS analysis

Peptide mixtures were analyzed by microflow capillary liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (ESI Q-TOF MS/MS). ESI–MS/MS tandem spectra were recorded in the automated MS to MS/MS switching mode, with an m/z-dependent set of collision offset values. Singly to quadruply charged ions were selected and fragmented, using argon as the collision gas. External calibration was performed with a solution of H3PO4 0.05% in H2O/MeCN 50/50. Mass data collected during RP–LC–MS/MS analysis were processed and converted into a PKL file to be submitted to the automated database searching Mascot, MS/MS Ions Search. Search parameters were parent tolerance 0.6 Da, fragment tolerance 0.3 Da, tryptic specificity allowing for up to 1 missed cleavage, database SwissProt [12,35].

Kinetic and binding data analysis

We analyzed kinetic and binding data using the software OriginPro7 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). The time courses of Prx2 membrane displacement, intracellular MetHb formation, and hemichrome membrane binding were normalized as a percentage of their total change. In particular, the initial amount of Prx2, determined by densitometric analyses, or the maximum amount of MetHb formation (49% of the total Hb content) or the total amount (nmol/ml ghost) of hemichromes bound to the membrane was set as 100%.

Fitting of the various time courses was performed using Eq. (1),

| (1) |

where a is the slope, b the offset, ci the amplitude of phase i, N the number of the phase, and ki the rate constant associated with each phase.

Because the dependence of both Prx2 membrane displacement and MetHb content exhibits a saturation behavior with increasing PHZ concentration, data were fitted to a hyperbola (Eq. (2)),

| (2) |

where Ymax represents the total amount of Prx2 detached from the membrane or MetHb formed and Kd the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant of Prx2–PHZ or Prx2–PHZ target complex or MetHb–PHZ complex from the membrane. Hemichrome membrane binding follows a linear dependence on PHZ concentration and was fitted to a least-squares linear regression.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the two-way analysis of variance algorithm for repeated measures between control and β-thalassemic mice. A difference with a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Total Prx2 expression is increased but membrane association is decreased in β-thalassemic mouse red cells

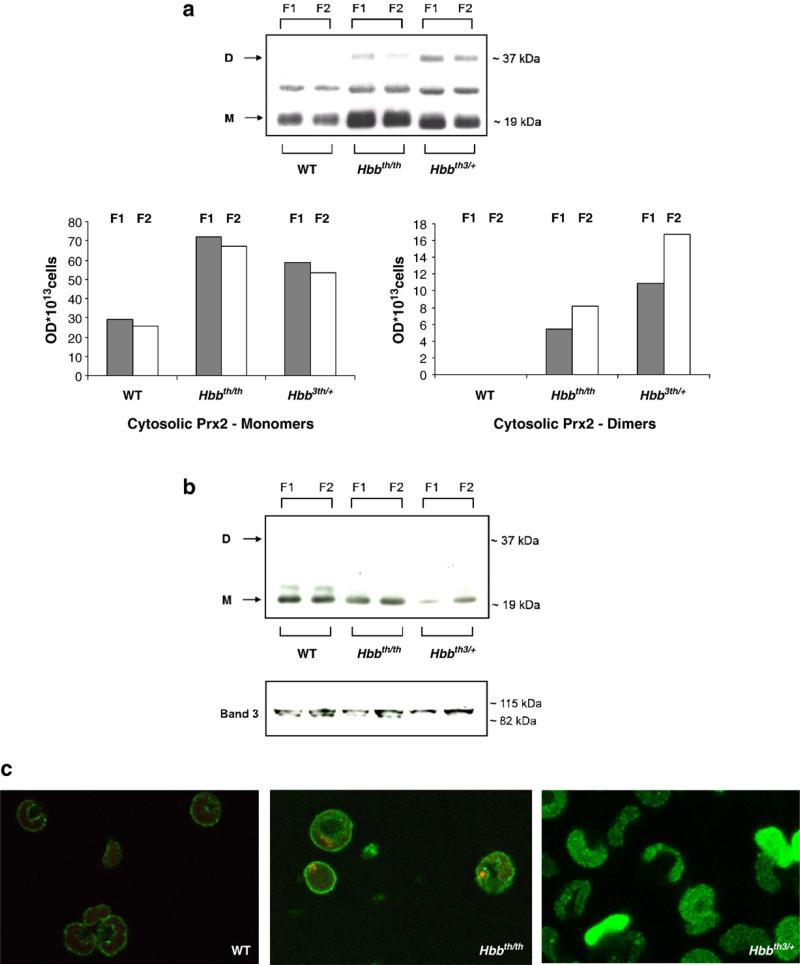

We studied Prx2 protein expression and localization in red cells from wild-type mice and two mouse models of β-thal: Hbbth/th, the naturally occurring β-thalassemic mouse, and Hbbth3/+, the transgenic mouse heterozygous for deletion of both b1 and b2 globin genes [24,37,38]. The β-thalassemic murine models showed hematological and biological features similar to those observed in human mild β-thalassemia intermedia (Hbbth/th) and more severe β-thalassemia intermedia (Hbbth3/+) (Table 1) [24,37,38]. Because β-thalassemia is characterized by a reduced red cell life span and increased reticulocyte count, we also fractionated the erythrocytes according to their density to better evaluate the possible effects of density and age on Prx2 protein expression and localization. For this purpose, we compared F1, a low-density reticulocyte-enriched fraction, with F2, the highest-density cell population, presumably containing many of the oldest erythrocytes [29]. No differences in Prx2 abundance were detected between F1 and F2 from either wild-type or the β-thalassemic mouse strains, indicating that cell density/age had no effect on Prx2 level (Fig. 1a, top). In contrast, the red cell cytosol fraction and total lysates from both β-thal models were found to contain higher levels of Prx2 than the normal mouse controls (Fig. 1a, top, and Supplemental Fig. 1Sa). In particular, Prx2 cytosolic dimers were observed only in β-thal red cells. When Prx2 cytosol levels were evaluated on a per-cell basis we observed that in both β-thalassemic mouse strains the relative distribution of Prx2 was shifted toward the dimers in F2, as expected for the oldest erythrocytes, reaching a value of approximately 10% in Hbbth/th and 25% in Hbbth3/+ (Fig. 1a, bottom). Fig. 1b shows that the membrane fraction of the β-thal red cells contains decreased amounts of Prx2. This result was evidenced by running the samples under both reducing and nonreducing conditions (data not shown). Interestingly the most severe β-thal model (Hbbth3/+) showed the highest levels of Prx2 dimers in the cytoplasmic fraction and the lowest level of membrane-bound Prx2. Importantly, no Prx2 dimers could be detected on the membranes of either control or β-thal mouse red cells (Fig. 1b). These data were further confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis of the corresponding gel bands. In these studies, Prx2 was identified at ~19 and ~37 kDa, corresponding to the Prx2 monomer and dimer, with the band present between these two Prx2 bands identified as an α-globin chain dimer cross-linked with a still-unidentified protein (see Supplementary Table S1) [30]. To further investigate the Prx2 oxidative state, we evaluated Prx2 cysteine sulfinic acid (Cys–SO2H) and cysteine sulfonic acid (Cys–SO3H) by immunoblot analysis. Overoxidized forms of Prx2 were not detectable in any samples (data not shown).

Table 1.

Hematological parameters and red cell cation content in wild-type and β-thalassemic mice

| Wild type (n = 12) | Hbbth/th (n = 12) | Hbbth3/+ (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hct (%) | 48.8 ± 0.2 | 30.1 ± 0.8* | 27.9 ± 0.9* |

| Hb (g/dl) | 15.3 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 0.5* | 7.5 ± 0.4* |

| MCV (fl) | 52.2 ± 1.1 | 38.2 ± 0.7* | 36.9 ± 0.1* |

| MCH (g/dl) | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.4* | 9.1 ± 0.1* |

| RDW (%) | 12.2 ± 0.2 | 31.5 ± 0.8* | 35.1 ± 0.8* |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 22.3 ± 1.2* | 23.2 ± 2.8* |

| MCVr (fl) | 54.7 ±1.2 | 44.9 ± 1.2* | 43.8 ± 0.6* |

| CHr (pg) | 14.5 ± 0.2 | 11.2 ± 0.3* | 10.9 ± 0.1* |

| Red cells [Na+] (mmol/kg Hb) | 26.8 ± 1.2 | 27.4 ± 0.8 | 26.7 ± 2.4 |

| Red cells [K+] (mmol/kg Hb) | 499 ± 16 | 382 ± 20* | 397 ± 12* |

Hct, hematocrit; Hb, hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean cell hemoglobin; RDW, red cell distribution width; MCVr, reticulocyte mean corpuscular volume; CHr, hemoglobin content of reticulocytes.

Fig. 1.

Prx2 expression and localization in wild-type and β-thalassemic mouse red cells. Red cells were previously fractionated according to density into fraction 1 (F1), corresponding to the light, reticulocyte-enriched fraction, and fraction 2 (F2), corresponding to the densest red cells and containing the oldest erythrocytes. (a) Top: immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of the red cell cytosol fraction from wild-type (WT) mice and two β-thal mouse models: Hbbth/th and Hbb3th/+. Gels were analyzed under nonreducing conditions. Prx2 was detected as monomers (M) or dimers (D). A representative experiment of six performed with similar results is shown. Bottom: the protein expression assessed by immunoblot analysis was quantified by densitometric analysis and adjusted per number of cells. Data are presented as the median (n = 6). (b) Immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of red cell ghosts from WT mice and two β-thal mouse models: Hbbth/th and Hbb3th/+. Expression of band 3 was used as the loading control for mouse red cells. Gels were analyzed under nonreducing conditions. Prx2 was detected as monomers or dimers. A representative experiment of six performed with similar results is shown. (c) Immunofluorescence staining with the anti-Prx2 antibody of fixed and permeabilized red cells from WT mice and two β-thal mouse models: Hbbth/th and Hbb3th/+. A representative experiment of four performed with similar results is shown (see also Supplemental Fig. 1Sb for secondary antibody controls).

To confirm the impact of the β-thalassemic pathology on the association of Prx2 with the membrane, the distribution of Prx2 within the various murine erythrocytes was also examined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1c, Prx2 displayed both membrane and cytosolic staining in normal erythrocytes, whereas in β-thal red cells Prx2 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm; moreover, the amount of Prx2 bound to the membrane was lower in Hbbth3/+ red cells than in Hbbth/th erythrocytes (Fig. 1c and Supplemental Fig. 1Sb). The punctate distribution of Prx2 on the red cell membrane of both normal and β-thal mice was evident with both monoclonal and polyclonal anti-Prx2 antibodies (data not shown), suggesting that Prx2 might organize into large complexes displaying brighter fluorescence intensity on the membrane.

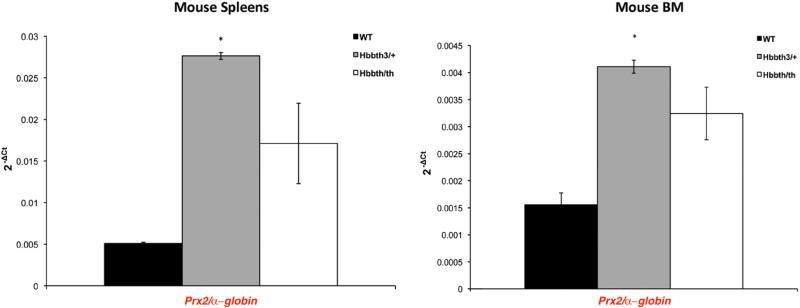

Then, we evaluated Prx2 gene expression in mouse bone marrow and spleens because extramedullar erythropoiesis is the major contributor to murine erythropoiesis [38–40]. As shown in Fig. 2, Prx2 gene expression was higher in spleens from both β-thal mouse models compared to wild-type mice. Both bone marrow and spleen from Hbbth3/+ mice showed a significantly increased Prx2 gene expression compared to wild-type mice (Prx2 gene expression in bone marrow from wild-type vs Hbbth3/+ P=0.009; Prx2 gene expression in spleen from wild-type vs Hbbth3/+ P=0.0004). In mild β-thal mice, we observed an increase in Prx2 gene expression that did not reach statistical significance compared to wild-type mice (Prx2 gene expression in bone marrow from wild-type vs Hbbth/th P=0.13; Prx2 gene expression in spleen from wild-type vs Hbbth/th P=0.081). These data indicate that the increased amount of Prx2 detected in β-thal red cells was related to the up-regulation of Prx2 gene expression during erythropoiesis and that β-thalassemic membrane oxidative damage is important in Prx2 membrane displacement.

Fig. 2.

Prx2 gene expression in mouse bone marrow and spleens. The Prx2 gene expression relative to that of the α-globin gene (Hba) was assessed in spleens and bone marrow (BM) from WT and both β-thal mouse models: Hbb3th/+ and Hbbth/th. The histograms show the mean values of 2–ΔCt in β-thal and wild-type mice. The relative gene expressions were calculated using the 2–ΔCt method. The ΔCt was calculated using the differences in the mean Ct between the genes and their internal controls [28]. The error bars in the histogram were determined by the standard error of the mean of the ΔCt values; *P<0.05 compared to wild type; n = 4.

Oxidative agents differentially affect Prx2 dimerization and translocation to the membrane

We evaluated Prx2 sensitivity in vitro to various oxidative agents: PHZ, diamide, and H2O2. We chose these compounds because of (i) their differences in the mechanism of oxidative stress, (ii) previous reports on the effects of H2O2 treatment on Prx2 in red cells [1,2], and (iii) the ability of PHZ to mimic β-thalassemic membrane oxidative damage [14,19,29,34,41].

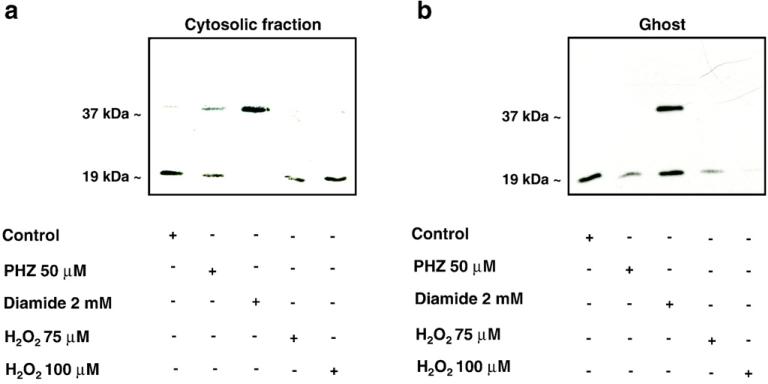

Wild-type mouse erythrocytes were treated with PHZ (50 μM), diamide (2 mM), and H2O2 (75 and 100 μM). The concentrations of the compounds were based on previous reports [2,15,18,21,29]. As shown in Fig. 3a, in the red cell cytoplasmic fraction we observed (i) slightly increased Prx2 dimerization in PHZ-treated red cells, (ii) complete Prx2 dimerization in diamide-treated erythrocytes, and (iii) no apparent Prx2 dimerization in H2O2, suggesting a different sensitivity of Prx2 to the various oxidant agents used (see also Supplemental Fig. 2S).

Fig. 3.

Effects of oxidative agents on Prx2 in mouse red cells. Immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of (a) red cell cytosolic fraction and (b) membrane (ghost) from wild-type mouse red cells (control) with and without PHZ (50 μM), diamide (2 mM), or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 75 and 100 μM) treatment. Bands at 19 and 37 kDa represent Prx2 monomers and dimers, respectively. Tween colloidal Coomassie-stained gels are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2S. Representative experiments of four performed with similar results are shown.

We then evaluated whether Prx2 partioning between the cytosol and the membrane might be differentially affected by diverse oxidants. As shown in Fig. 3b, Prx2 membrane association was (i) reduced in PHZ-treated red cells, (ii) increased in diamide-treated erythrocytes as both monomers and dimers, and (iii) reduced to almost undetectable amounts in H2O2-treated red cells (see also Supplemental Fig. 2S). These data show that PHZ and H2O2 treatments have similar effects. PHZ reacts with dioxygen and generates a radical species that in turn could attack the reduced iron of Hb producing MetHb and hemichromes with formation of superoxide that could be finally converted into hydrogen peroxide. Following this view, PHZ not only acts to increase MetHb levels but also is a source of H2O2. Instead, diamide effects are related to the reactivity of this cysteine-reacting agent. Thus, the accumulation of dimers in both the cytoplasm and the red cell membrane treated with diamide is an effect of this oxidant mode of action.

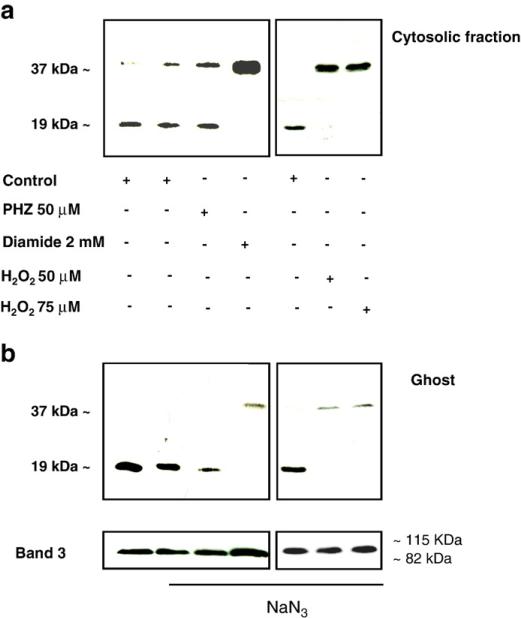

Because Prx2 has been previously described to protect normal and β-thalassemic red cells against H2O2 treatment [1,42], we reevaluated the effects of these compounds in red cells pretreated with sodium azide to inhibit the catalase activity. Catalase inhibition caused an evident increase in cytosolic Prx2 dimerization, reflecting a higher oxidative environment due to the absence of the efficient hydrogen peroxide-scavenging catalase and its translocation to the membrane in H2O2-treated red cells. A moderate or no effect in diamide- and PHZ-treated red cells was observed (Figs. 4a and b). The insensitivity of PHZ to sodium azide could be due to the fact that the active form of PHZ generated in the red cells is a free radical that is not scavenged by catalase and that triggers hydrogen peroxide formation [43].

Fig. 4.

Effects of inhibition of catalase activity by Na azide on Prx2 sensitivity to oxidative agents in mouse red cells. Immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of (a) red cell cytosolic fraction and (b) membrane (ghost) from wild-type mouse red cells (control) treated with PHZ (50 μM), diamide (2 mM), or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 50, 75 μM) in the presence of sodium azide. Bands at 19 and 37 kDa represent Prx2 monomers and dimers, respectively. Expression of band 3 was used as loading control for mouse red cells. Representative experiments of three performed with similar results are shown.

We then asked whether the membrane-associated Prx2 was attached to the bilayer or cytoskeletal network. Each cell preparation was extracted with Triton X-100 and the cytoskeletal pellets and soluble fractions were investigated by immunoblot analysis [34]. Prx2 was almost undetectable in the cytoskeleton fractions, indicating that Prx2 is mainly associated with the detergent-extractable fraction of the membrane (data not shown).

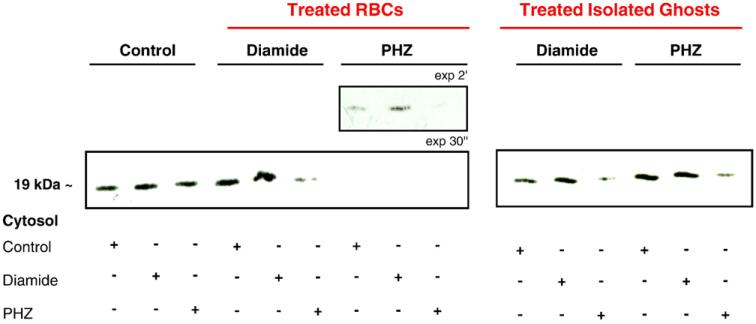

Pretreatment of red cell membrane with oxidants affects Prx2 binding

To evaluate whether the perturbation seen in Prx2–membrane interactions in oxidized red cells was due to modifications occurring on the Prx2 molecule or in the membrane, we compared Prx2 membrane association in control and diamide- or PHZ- (β-thal-like) treated membranes with the cytoplasmic red cell fractions obtained from control and diamide- or PHZ-treated erythrocytes. Diamide and PHZ red cell treatments showed little or no effect on Prx2 translocation in control and diamide-treated membranes (Fig. 5, lanes 1–6). In contrast, we observed a remarkable loss of interactions between Prx2 and the membranes obtained from PHZ-treated red cells (Fig. 5, lanes 7–9).

Fig. 5.

Prx2 shows different degrees of affinity to native or oxidized red cell membrane. Immunoblot analysis (under reducing conditions) with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of red cell membrane from native red cells (control, lanes 1–3), red cells exposed to diamide (2 mM, lanes 4–6) or PHZ (50 μM, lanes 7–9), and isolated red cell membranes treated with diamide (2 mM, lanes 10–12) or PHZ (50 μM, lanes 13–15) incubated with the cytoplasmic fraction of control or diamide- (2 mM) or PHZ- (50 μM) treated red cells. Tween colloidal Coomassie-stained gels are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3S. A representative experiment of three performed with similar results is shown.

Because PHZ strongly interacts with hemoglobin, producing hemichromes that bind to the cytoplasmic domain of band 3, to have an indication of the hemoglobin involvement, we treated isolated red cell membranes with PHZ or diamide and we measured Prx2 binding (Fig. 5, see also Supplemental Fig. 3S). This experimental approach allowed us to clean the membrane from hemichromes or other heme compounds that were bound to their docking sites on the membrane. Direct treatment of the isolated membranes with oxidants did not apparently influence the binding of Prx2. Therefore, in intact red cells PHZ may inhibit Prx2 binding to the membrane by masking the docking sites of Prx2 on the membrane, possibly by increasing the association of denatured hemoglobin to the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 (Fig. 5, lanes 10–15, see also Supplemental Fig. 3S). This last observation also raises the possibility that the band 3 cytoplasmic domain may represent the major binding site for Prx2 on the membrane.

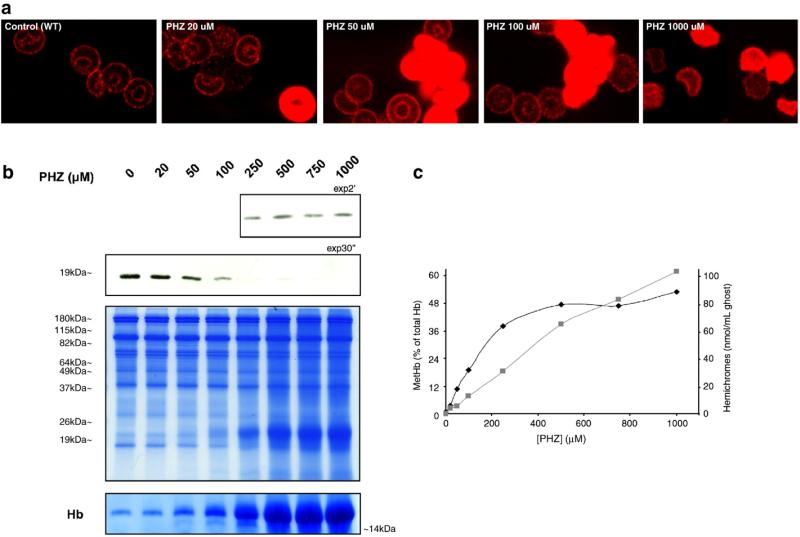

Prx2 is displaced from PHZ-treated red cell membrane in a dose- and time-dependent manner and correlates with the binding of hemichromes to the membrane

We treated wild-type mouse red cells with various concentrations of PHZ and the localization of Prx2 was examined by multiple techniques. As shown in the confocal micrographs of Fig. 6a, exposure to increasing concentrations of PHZ promoted greater displacement of Prx2 from the membrane (see also data in Supplemental Fig. 4S). It was also interesting to note that after PHZ treatment the cells stained brighter with antibodies to Prx2, suggesting that Prx2 epitopes might be more accessible to antibodies when free in the cytoplasm than when bound to the membrane (also confirmed with a different monoclonal antibody specific for Prx2; data not shown). Moreover, this increased displacement of Prx2 was also evident in immunoblot analyses (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Prx2 is displaced from the membrane in β-thalassemic-like red cells obtained by PHZ treatment. (a) Immunofluorescence staining with the anti-Prx2 antibody of fixed and permeabilized WT red cells untreated and treated with increasing concentrations of PHZ (20, 50, 100, 1000 μM). A representative experiment of four performed with similar results is shown (see also Supplemental Fig. 4S for secondary antibody controls). (b) Immunoblot analysis with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of membrane (ghost) from wild-type mouse red cells treated with PHZ (in μM: 20, 50, 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000). At the bottom two Tween colloidal Coomassie-stained gels are shown: one is a protein loading control, increasing globin chains bound to the membrane related to the PHZ treatment in a dose-dependent manner are present at 19–26 kDa, as previously reported by Schrier et al. [15]; the other shows the band relative to Hb binding to the membrane during the PHZ treatment (from the Coomassie-stained gel T14% loaded with the same samples). A representative experiment of four performed with similar results is shown. (c) MetHb levels (black diamond) and the membrane-bound hemichromes (grey square). These parameters were evaluated in WT red cells untreated and treated with increasing concentrations of PHZ (in μM: 20, 50, 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000). Data are presented as median values (n = 3).

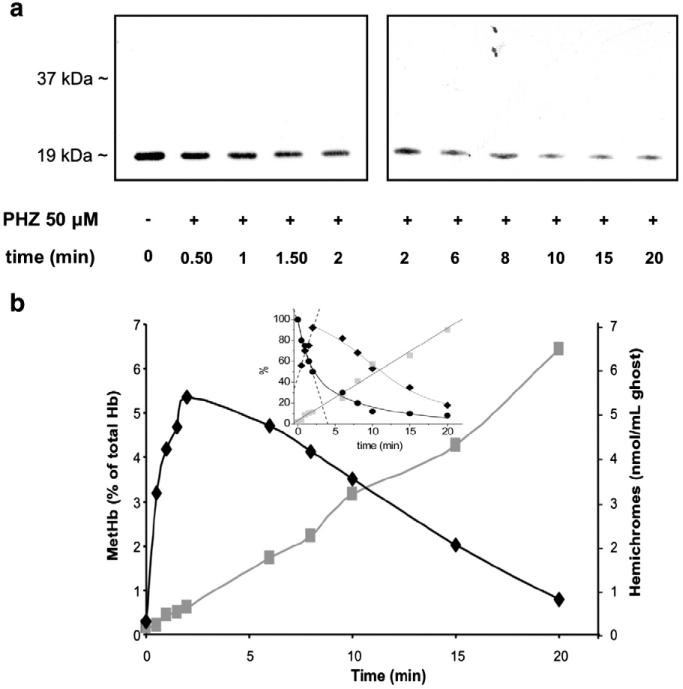

In samples treated with PHZ, we measured intracellular levels of MetHb as a marker of the oxidative stress and the amount of hemichrome binding to the membrane. Increasing concentrations of PHZ were found to correlate with increased levels of both MetHb and hemichrome binding to the membrane and the displacement of Prx2 from the membrane, as determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 6c). Then we further investigated the linkage between Prx2 membrane displacement and hemichrome binding to the membrane by correlating the kinetics of the two processes. As shown in Figs. 7a and b, Prx2 was displaced from the membrane concomitant with hemichrome membrane binding, providing further evidence that PHZ, used to mimic β-thalassemic membrane oxidative damage, may block Prx2 binding to the membrane through the masking of its membrane binding sites with hemichromes, similar to what we observed in vivo in β-thal red cells (see also Supplemental Fig. 5S). A kinetic analysis of Prx2 membrane displacement together with intracellular MetHb content and hemi-chrome membrane association (Fig. 7b, inset) allows us to calculate the rate constants for the different kinetic processes observed. Using Eq. (1) (see Material and methods) we calculated k1 and k2 for the fast and slow processes of both Prx2 membrane displacement and MetHb intracellular content. It could be observed that k1 for Prx2 membrane displacement is 24±2 min–1 and k2 is 0.18±0.04 min–1; k1 for MetHb fast ascending phase is 23±3 min–1 and k2 = 3.5±0.8 min–1. It could be noted that k1 for both Prx2 displacement and MetHb fast increase are in good agreement. The time course of hemichrome membrane binding fits to a linear regression with a rate constant of 4.4±0.2 min–1, this value being in good agreement with k2 of the MetHb slow descending phase. These data could be interpreted as a time coincidence of Prx2 membrane displacement and MetHb increase. Then, there follows a slow phase in which MetHb seems to convert to heme compound membrane binding with further slow dissociation of Prx2 from the membrane.

Fig. 7.

Prx2 displacement correlates with the amount of hemichromes bound to the membrane in β-thalassemic-like red cells obtained by PHZ treatment. (a) Immunoblot analysis (WB) with specific anti-Prx2 antibody of red cell membrane from WT with and without 50 μM PHZ treatment at various time points (from 0 to 20 min). Tween colloidal Coomassie-stained gel is shown in Supplemental Fig. 5S. A representative experiment of four performed with similar results is shown. (b) Methemoglobin levels expressed as percentage of total hemoglobin (black diamond) and membrane-bound hemichromes expressed as nmol hemichromes/ml of ghost (grey square) measured in wild-type red cells treated with 50 μM PHZ. Data are presented as median values (n = 3). The inset shows the relative amounts, expressed in percentage, of Prx2 membrane displacement (●), MetHb formation (◆), and hemichrome membrane binding( ), determined as described under Material and methods, plotted versus time and fitted to Eq. (1) (solid lines). Dashed lines represent fitting to a least-squares linear regression applied to linear time changes (hemichromes binding) or linear phases of two-phase exponential curves (Prx2 displacement and MetHb levels) where the slope of the linear regression is identical to the rate constant (k1) of the fast phase in a two-phase model (Eq. (1)).

), determined as described under Material and methods, plotted versus time and fitted to Eq. (1) (solid lines). Dashed lines represent fitting to a least-squares linear regression applied to linear time changes (hemichromes binding) or linear phases of two-phase exponential curves (Prx2 displacement and MetHb levels) where the slope of the linear regression is identical to the rate constant (k1) of the fast phase in a two-phase model (Eq. (1)).

The dissociation of Prx2 from the membrane, as well as MetHb content, is also PHZ concentration-dependent (Supplemental Fig. 6S). Fitting the data to Eq. (2) (see Material and methods) allows us to determine an apparent equilibrium dissociation value Kd equal to 128±45 μM. This means that an intermediate between Prx2 and either PHZ itself or, more probably, a PHZ target would form. MetHb formation also shows a saturation behavior with a Kd = 139±31 mM. The similarity of the Kd values for Prx2 and MetHb might account for a possible common intermediate species (Fig. 7b, inset). Hemichrome membrane binding proceeds in a linear manner on PHZ concentration with a second-order constant of 1.03±0.05 %units×μM–1.

Discussion

Here, we found increased expression of Prx2 in β-thalassemic mouse red cells, most likely as an adaptive response to heightened oxidative pressures experienced by these cells. Indeed, previous reports in other cell types have shown that oxidative stress can up-regulate Prx2 expression and that genetically modified cells over-expressing Prx2 are generally more protected from severe oxidative stress [44–47]. Because an increase in Prx2 expression was also seen in the spleens of the β-thalassemic mice (i.e., the main site of murine erythropoiesis), it is conceivable that the up-regulation of Prx2 expression might serve to protect against apoptotic signals related to increased production of reactive oxygen species. Indeed, in preliminary experiments we have observed increased Prx2 expression during late-phase erythropoiesis in vitro in human β-thalassemic progenitors (De Franceschi, Turrini, and Cappellini, unpublished data).

However, the evidence showing Prx2 membrane displacement from the red cell membrane in β-thalassemic mice was totally unexpected and drove us to consider that the β-thalassemic membrane oxidative damage might be important in Prx2 partitioning between the cytosol and the membrane. This view was corroborated by the fact that the fraction of protein displaced was more highly oxidized to its dimer in the cytosol. The studies with oxidant agents showed differences in Prx2 behavior and translocation to the membrane in response to the various oxidants (Fig. 3).

In diamide-treated red cells, Prx2 membrane association was increased and it was present as both monomers and dimers. In contrast, Prx2 association with the membrane was markedly reduced in both H2O2- and PHZ-treated red cells, which more closely mimic the β-thalassemic red cell membrane damage. When NaN3 was used to inhibit catalase [30], Prx2 dimerization both in cytosol and on the membrane was prominent only in diamide- and H2O2-treated red cells and not in PHZ-treated erythrocytes, suggesting that catalase does not participate in Prx2 membrane displacement in PHZ-treated red cells. In fact, catalase could not affect the radical intermediate generated by PHZ that subsequently acts as oxidizing agent for the ferrous atom of Hb, leading to the formation of MetHb, peroxide, and hemichromes. It should be taken into account that diamide chemical reactivity as an oxidant probe for thiols could alter the proportion between monomers and dimers but it does not reflect the pathophysiological oxidant conditions of β-thalassemic red cells. In addition, in PHZ-treated β-thal-like red cells, we observed significant displacement of Prx2 from the membrane, where concomitant significant intracellular MetHb levels were reached and hemichrome formation was noted.

A kinetic analysis of Prx2 membrane displacement, MetHb formation, and hemichrome membrane binding (Fig. 7b, inset) shows that this process is at least biphasic and suggests a direct correlation between Prx2 displacement and MetHb initial increase. In fact, the observed rate constant (k1 = 24±2 min–1) for Prx2 displacement is similar to that for MetHb formation (k1 = 23±3 min–1). Thereafter, MetHb levels decrease concomitant with hemichrome membrane binding (k2 for MetHb decrease = 3.5±0.8 min–1 and the rate constant for hemichrome membrane binding = 4.4±0.2 min–1) while further Prx2 displacement occurs (k2 = 0.18±0.04 min–1). This suggests that an increase in the oxidant red cell microenvironment leads to a higher proportion of denatured and oxidized Hb recovered on the membrane as hemichromes. The dependence of Prx2 displacement on PHZ concentration (Supplelemental Fig. 6S) allows us to calculate an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant of Prx2 from a PHZ target (Kd~130 μM) on the membrane.

Previous reports in various cell types have shown that Prxs bind to integral membrane proteins or cell membranes [5,48]. In our model PHZ might unfavorably affect the possible binding sites of Prx2 on the red cell membrane with subsequent reduction in Prx2 membrane translocation. This phenomenon may be possibly ascribed to denatured Hb (hemichromes) binding to band 3 generated by PHZ treatment as supported by the Prx2 membrane displacement concomitant with hemichrome membrane binding, indicating that PHZ blocks the Prx2 binding to the membrane through the masking of its docking sites by hemichromes [18,21].

In conclusion, in β-thalassemic mice, Prx2 gene expression is up-regulated. In circulating β-thal red cells, the cytoplasmic Prx2 is more abundant, present in its oxidized/dimerized form and accompanied by decreased levels of membrane-bound Prx2. These findings correlate with the clinical severity of murine β-thalassemic models. This phenomenon is mimicked by oxidant treatments with PHZ in β-thal-like red cells, characterized by Prx2 displacement from the membrane. The functional consequences of these observed changes in Prx2 distribution in β-thalassemic red cells remain to be elucidated. We could postulate that the masking of Prx2 membrane binding sites by hemichromes and the accumulation of its oxidized/dimerized state in the cytoplasm may affect Prx2 antioxidant efficiency on β-thalassemic membrane proteins, therefore contributing to their lack of repair of oxidative insults. The abnormally low ability of Prx2 to translocate to the membrane in β-thalassemic and in β-thalassemic-like (PHZ) red cells might represent a new additional factor contributing to the severity of red cell membrane damage in β-thalassemic red cells and to the shortening of β-thalassemic red cell survival.

Thus, the oxidant-specific behavior of Prx2 is indicative on one hand of its specificity of action and on the other of the multiplicity of mechanisms in which this protein could be involved, depending on the cellular microenvironment. Prx2 membrane translocation together with its monomeric or dimeric arrangement could be a signal of a complex relay of responses to which Prx2 takes part. Further studies will be required to clarify Prx2 function and regulation in response to cellular stress in normal and diseased red cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grant GM24417 (P.S.L.), a Telethon grant GP07007 (L.D.F.), and PRIN 2008 (L.D.F.).

Abbreviations

- Prx2

peroxiredoxin 2

- β-thal

β-thalassemia

- RBC

red blood cell

- PHZ

phenylhydrazine

- MetHb

methemoglobin

- Hb

hemoglobin

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.05.003.

References

- 1.Low FM, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Peroxiredoxin 2 and peroxide metabolism in the erythrocyte. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008;10:1621–1630. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manta B, Hugo M, Ortiz C, Ferrer-Sueta G, et al. The peroxidase and peroxynitrite reductase activity of human erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009;484:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trujillo M, Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Peroxynitrite detoxification and its biologic implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008;10:1607–1620. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore RB, Shriver SK. Protein 7.2b of human erythrocyte membranes binds to calpromotin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;232:294–297. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore RB, Shriver SK, Jenkins LD, Mankad VN, et al. Calpromotin, a cytoplasmic protein, is associated with the formation of dense cells in sickle cell anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 1997;56:100–106. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199710)56:2<100::aid-ajh5>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroder E, Littlechild JA, Lebedev AA, Errington N, et al. Crystal structure of decameric 2-Cys peroxiredoxin from human erythrocytes at 1.7 A resolution. Structure. 2000;8:605–615. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner E, Luche S, Penna L, Chevallet M, et al. A method for detection of overoxidation of cysteines: peroxiredoxins are oxidized in vivo at the active-site cysteine during oxidative stress. Biochem. J. 2002;366:777–785. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen P, Rasmussen DE, Kristensen BI. Properties of thiol-specific antioxidant protein or calpromotin in solution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;262:127–131. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocha S, Vitorino RM, Lemos-Amado FM, Castro EB, et al. Presence of cytosolic peroxiredoxin 2 in the erythrocyte membrane of patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2008;41:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plishker GA, Chevalier D, Seinsoth L, Moore RB. Calcium-activated potassium transport and high molecular weight forms of calpromotin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:21839–21843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore RB, Mankad MV, Shriver SK, Mankad VN, Plishker GA. Reconstitution of Ca2+-dependent K+ transport in erythrocyte membrane vesicles requires a cytoplasmic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:18964–18968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biondani ATF, Carta F, Mattè A, Filippini A, Siciliano A, Beuzard Y, De Franceschi L. Heat-shock protein-27,-70 and peroxiredoxin-II show molecular chaperone function in sickle red cells: evidence from transgenic sickle cell mouse model. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2008;2:706–719. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TH, Kim SU, Yu SL, Kim SH, et al. Peroxiredoxin II is essential for sustaining life span of erythrocytes in mice. Blood. 2003;101:5033–5038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Advani R, Rubin E, Mohandas N, Schrier SL. Oxidative red blood cell membrane injury in the pathophysiology of severe mouse beta-thalassemia. Blood. 1992;79:1064–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrier SL, Mohandas N. Globin-chain specificity of oxidation-induced changes in red blood cell membrane properties. Blood. 1992;79:1586–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuypers FA, Yuan J, Lewis RA, Snyder LM, et al. Membrane phospholipid asymmetry in human thalassemia. Blood. 1998;91:3044–3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan J, Kannan R, Shinar E, Rachmilewitz EA, Low PS. Isolation, characterization, and immunoprecipitation studies of immune complexes from membranes of beta-thalassemic erythrocytes. Blood. 1992;79:3007–3013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannu F, Arese P, Cappellini MD, Fiorelli G, et al. Role of hemichrome binding to erythrocyte membrane in the generation of band-3 alterations in beta-thalassemia intermedia erythrocytes. Blood. 1995;86:2014–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Advani R, Sorenson S, Shinar E, Lande W, et al. Characterization and comparison of the red blood cell membrane damage in severe human alpha- and beta-thalassemia. Blood. 1992;79:1058–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Franceschi L, Turrini F, Honczarenko M, Ayi K, et al. In vivo reduction of erythrocyte oxidant stress in a murine model of beta-thalassemia. Haematologica. 2004;89:1287–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turrini F, Mannu F, Cappadoro M, Ulliers D, et al. Binding of naturally occurring antibodies to oxidatively and nonoxidatively modified erythrocyte band 3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1190:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang B, Kirby S, Lewis J, Detloff PJ, et al. A mouse model for beta 0-thalassemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11608–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Franceschi L, Rouyer-Fessard P, Alper SL, Jouault H, et al. Combination therapy of erythropoietin, hydroxyurea, and clotrimazole in a beta thalassemic mouse: a model for human therapy. Blood. 1996;87:1188–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Franceschi L, Daraio F, Filippini A, Carturan S, et al. Liver expression of hepcidin and other iron genes in two mouse models of beta-thalassemia. Haematologica. 2006;91:1336–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn MC, Melnick RL, Ye F, Portier CJ. Pharmacokinetics of sodium nitrite-induced methemoglobinemia in the rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:676–683. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herold S, Rock G. Reactions of deoxy-, oxy-, and methemoglobin with nitrogen monoxide: mechanistic studies of the S-nitrosothiol formation under different mixing conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6623–6634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayi K, Turrini F, Piga A, Arese P. Enhanced phagocytosis of ring-parasitized mutant erythrocytes: a common mechanism that may explain protection against Falciparum malaria in sickle trait and beta-thalassemia trait. Blood. 2004;104:3364–3371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capasso M, Avvisati RA, Piscopo C, Laforgia N, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in Italian preterm infants: association between interleukin-10–1082 G/A polymorphism and respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr. Res. 2007;61:313–317. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318030d108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivieri O, De Franceschi L, Capellini MD, Girelli D, et al. Oxidative damage and erythrocyte membrane transport abnormalities in thalassemias. Blood. 1994;84:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low FM, Hampton MB, Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Peroxiredoxin 2 functions as a noncatalytic scavenger of low-level hydrogen peroxide in the erythrocyte. Blood. 2007;109:2611–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantaleo A, Ferru E, Giribaldi G, Mannu F, et al. Oxidized and poorly glycosylated band 3 is selectively phosphorylated by Syk kinase to form large membrane clusters in normal and G6PD-deficient red blood cells. Biochem. J. 2009;418:359–367. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peskin AV, Low FM, Paton LN, Maghzal GJ, et al. The high reactivity of peroxiredoxin 2 with H2O2 is not reflected in its reaction with other oxidants and thiol reagents. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11885–11892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Franceschi L, Fumagalli L, Olivieri O, Corrocher R, et al. Deficiency of Src family kinases Fgr and Hck results in activation of erythrocyte K/Cl cotransport. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:220–227. doi: 10.1172/JCI119150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bordin L, Ion-Popa F, Brunati AM, Clari G, Low PS. Effector-induced Syk-mediated phosphorylation in human erythrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1745:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Franceschi L, Biondani A, Carta F, Turrini F, et al. PTPepsilon has a critical role in signaling transduction pathways and phosphoprotein network topology in red cells. Proteomics. 2008;8:4695–4708. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantaleo A, Giribaldi G, Mannu F, Arese P, Turrini F. Naturally occurring anti-band 3 antibodies and red blood cell removal under physiological and pathological conditions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008;7:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adamsky K, Weizer O, Amariglio N, Breda L, et al. Decreased hepcidin mRNA expression in thalassemic mice. Br. J. Haematol. 2004;124:123–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Libani IV, Guy EC, Melchiori L, Schiro R, et al. Decreased differentiation of erythroid cells exacerbates ineffective erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2008;112:875–885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Socolovsky M, Nam H, Fleming MD, Haase VH, et al. Ineffective erythropoiesis in Stat5a(–/–)5b(–/–) mice due to decreased survival of early erythroblasts. Blood. 2001;98:3261–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivella S, May C, Chadburn A, Riviere I, Sadelain M. A novel murine model of Cooley anemia and its rescue by lentiviral-mediated human beta-globin gene transfer. Blood. 2003;101:2932–2939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bordin L, Brunati AM, Donella-Deana A, Baggio B, et al. Band 3 is an anchor protein and a target for SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase in human erythrocytes. Blood. 2002;100:276–282. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott MD. H2O2 injury in β-thalassemic erythrocytes: protective role of catalase and the prooxidant effects of GSH. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misra HP, Fridovich I. The oxidation of phenylhydrazine: superoxide and mechanism. Biochemistry. 1976;15:681–687. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabilloud T, Heller M, Gasnier F, Luche S, et al. Proteomics analysis of cellular response to oxidative stress: evidence for in vivo overoxidation of peroxiredoxins at their active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19396–19401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang P, Liu B, Kang SW, Seo MS, et al. Thioredoxin peroxidase is a novel inhibitor of apoptosis with a mechanism distinct from that of Bcl-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30615–30618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang SW, Chae HZ, Seo MS, Kim K, et al. Mammalian peroxiredoxin isoforms can reduce hydrogen peroxide generated in response to growth factors and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6297–6302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phalen TJ, Weirather K, Deming PB, Anathy V, et al. Oxidation state governs structural transitions in peroxiredoxin II that correlate with cell cycle arrest and recovery. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:779–789. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cha MK, Yun CH, Kim IH. Interaction of human thiol-specific antioxidant protein 1 with erythrocyte plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6944–6950. doi: 10.1021/bi000034j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.