The vertebrate immune system is remarkable because it can recognize virtually any foreign material or antigen and yet not react against itself except in those rare cases when autoimmunity results. Over the last 20 years the mechanisms by which antigens are recognized by the B cell antigen receptor (Ig) and the T cell antigen receptor (TcR) have been well characterized. Both of these groups of proteins are built up from Ig-like domains. The variable or V domain provides the specificity to react with the range of foreign antigens and constant or C domains provide the effector functions. One fascinating question is how such a complex system evolved, and this is the topic addressed by a paper in this issue of PNAS by Strong et al. (1).

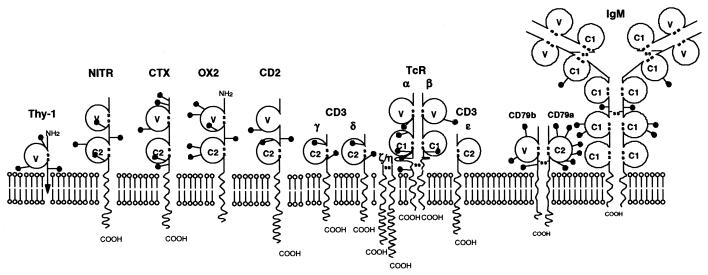

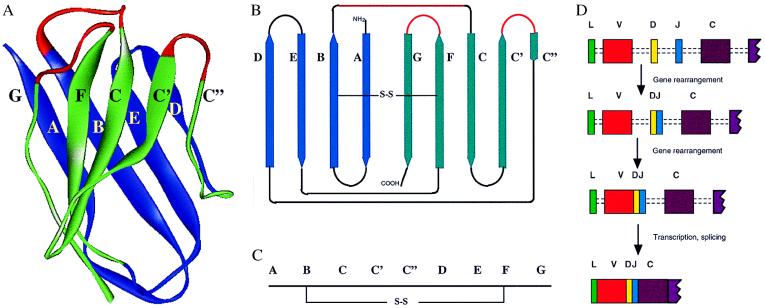

The domain structure of Igs and TcRs is illustrated in Fig. 1. Both V and C domains have similar structures called the Ig fold, which is formed by antiparallel β-strands arranged into two sheets linked by a disulfide bond (Fig. 2). V domains can be distinguished from C domains because they show the variability associated with antigen recognition and also the domain is longer with two extra strands being accommodated in the middle of the domain (C′ and C" in Fig. 2). The binding site is built up from two chains in both the TcR (e.g., αβ) and Igs (heavy and light chains). Additional chains are associated with both Ig and the TcR that mediate signaling to the cytoplasm. CD79a and CD79b associate with membrane Ig and contain an immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motif (ITAM) motif involved in signal transduction. The TcR heterodimer is associated with the CD3 chains including ζη, which contain ITAM motifs. The variability that allows Ig and TcR to bind such a diverse range of proteins is determined largely by three loops in each chain at the top of the domain (colored red in Fig. 2), which show particular variability (the hypervariable regions).

Figure 1.

Blob diagram to illustrate various proteins containing IgSF domains, including the antigen receptors. The IgSF domains are illustrated by open circles and marked V, C1, or C2 according to sequence patterns and size (7). The lollipop symbols indicate the approximate position of N-linked glycosylation sites. The arrow in Thy-1 indicates the presence of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor. The protein data for Thy-1, Ig, TcR, CD2, and OX2 are from ref. 10, the NITR from Strong et al. (1) and CTX from ref. 14.

Figure 2.

The Ig fold. (A) Ribbon diagram of the x-ray crystallography structure of the heavy chain V region of human myeloma New (Protein Database 7fab). (B) Schematic representation of the strands that form the two sheets of the fold. In both A and B the ABED sheet is colored blue and the GFCC′C" sheet is green. The three loops that make up the hypervariable regions are indicated in red. (C) Linear representation of the strands in B. Note C domains lack the extra loops C′ and C". C2 domains lack the C" strand. (D) Scheme for the generation of individual TcRβ or heavy chains whereby particular V region, D and J segments are selected and recombined to form a VDJ segment. After transcription the introns are spliced out to give the full mRNA. Further exons coding for C regions and transmembranes are not included for simplicity.

How is the variability brought about? The V domain is built up from multiple copies of gene segments by recombination in somatic cells. The bulk of the domain is coded by V segments and this is combined with one of the D and J segments to form a VDJ exon, which then is spliced to C domains after transcription (Fig. 2D). This joining is not completely precise and additional, so-called N-region diversity also is introduced (there is some variation in detail between the different antigen receptors; ref. 2). The J region makes up most of the final β-strand (G in Fig. 2) and has a characteristic pattern of sequences (see figure 3C of ref. 1). How did this wonderfully complex system of antigen recognition molecules arise in evolution? When Igs were being sequenced in the mid-1960s it soon became apparent that they were built up of regions with similar sequence patterns, suggesting that the V and C domains evolved by gene duplication (3, 4). Sequence data for MHC antigens and β2 microglobulin indicated that Ig-like sequences might be present in other proteins associated with the immune response. When the brain antigen Thy-1 and subsequently hundreds of other proteins were found to contain Ig-related sequences, it was apparent that the Ig fold had been in existence before the rearranging receptors of the adaptive immune system (5–7). These regions of sequence often are called Ig superfamily (IgSF) or Ig-like domains to distinguish them from domains of Igs themselves. Rather than being something special for antigen recognition it turned out that the Ig fold was particularly good for mediating interactions and was widely used e.g., in the nervous system. IgSF domains can be classified V, C1, C2, and I according to sequence patterns and overall length (7–9). It should be noted that IgSF V domains show sequence similarity to V domains of Ig itself but they do not show the variability found in the Ig or TcR V domains that is generated by rearrangement (see above). Thus the recognition of antigens by TcR and Ig is the highly evolved and rather sophisticated interaction of a domain type that has been used extensively in evolution (7, 10).

How did the IgSF domain evolve and how was it adapted to the special case of antigen recognition? It seems likely that IgSF domains evolved to mediate interactions, probably at the cell surface (7). Gene duplication and mutation led to a large family of proteins. The paper by Strong et al. (1) addresses the question of whether one could recognize a possible precursor of the antigen binding V domain before the characteristic rearranging genes that code for antibodies and TcR discussed above. Thus in searching for the primitive V domains one would like to find a group of V-region sequences with putative J-like sequences. It seems reasonable to suppose that the J region became separated at some stage possibly by the insertion of a transposable element (11). Clearly the introduction of a number of J regions immediately increases the possible repertoire considerably especially when one takes into account the D regions and N-region diversity. One might expect the V domain to be associated with a C domain and the protein to be membrane associated with the ability to signal via interactions with its cytoplasmic region.

The pufferfish studied by Strong et al. (1) does not have recognizable TcR or Ig but has a compact genome, making it a suitable species to look for a family of proteins that might have been precursors to the current V domains and which might mediate immune reactions by an innate mechanism. Strong et al. use PCR technology to isolate a family of 26 genes called NITR or novel immune-type receptor. The NITR contain two IgSF domains, a transmembrane region and a cytoplasmic region that in some cases contains ITIM or inhibitory tyrosine motifs. These motifs often are found in nonrearranging receptors such as natural killer receptors but not in TcR or Ig, which are associated with proteins containing ITAM (activating motifs). The membrane proximal domain is termed V/C2 as it is similar to both V and C2 domains.

About one-third of the proteins characterized at the surface of human and rodent leukocytes contain IgSF domains and of these 45% contain two domains and the majority of these again have the V domain-C2 domain-transmembrane organization found in NITR (10). These include the CD2 subfamily (CD2, CD48, CD58, CD84, and 2B4) (12) and others such as OX2, CD33, CD80, and CD86 (10, 13). TcR and Ig light chain also contain an amino-terminal V domain with a C1 domain that has sequence patterns found only in the antigen receptors and MHC antigens.

It is possible that the immediate precursors to the first rearranging antigen receptors are still present in higher vertebrates, and it will be interesting to see in what species NITR homologues can be found. Similarly are there homologues of the vertebrate proteins with a V-C2-transmembrane arrangement with a nonrearranging J-like segment mentioned above? One interesting example is the CTX family of genes found in amphibians and humans, but they do not show the combination of conservation in the C2 domain coupled with the extensive variation in the V domains seen in the NITR (14).

Clearly there is a major step in going from a limited number of genes coding for the primitive receptors, which may be related to the NITR to the rearranging TcR and Ig. One theory is that this change occurred during the transition from jawless to jawed fish, which might have resulted in exposure to increased localized injuries and infections (15). The ability to make many more antigen receptors could have been a significant selective advantage and led to the development of the adaptive immune system.

There is no doubt that the discovery of the NITR family of proteins is a fascinating contribution to our thinking of the evolution of antigen receptors and the adaptive immune system. It will be of interest to find what these proteins interact with. Are the V domains recognizing foreign proteins in a type of primitive immunity? Or do they interact with self proteins at the surface of other cells or soluble proteins? The extremely high conservation of the membrane proximal domain of NITR suggests that it may be involved in a conserved interaction possibly in a cis manner with another cell surface protein, possibly analogous to CD3 chains and involved in transmitting signals. Do they form homodimers or heterodimers? Are there homologues of the NITR in vertebrates where there is an established adaptive system and if so are they involved in the immune system?

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Gavin Wright and Don Mason for helpful comments. This work was supported by the U.K. Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 15080.

References

- 1.Strong S J, Mueller M G, Litman R T, Hawke N A, Haire R N, Miracle A L, Rast J P, Amemiya C T, Litman G W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15080–15085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway C, Travers P. Immunobiology. London: Garland; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer S J, Doolittle R F. Science. 1966;153:13–25. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3731.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill R, Delaney R, Fellows R, Lebovitz H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1762–1769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.6.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell D G, Williams A F, Bayley P M, Reid K B. Nature (London) 1979;282:341–342. doi: 10.1038/282341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams A F, Gagnon J. Science. 1982;216:696–703. doi: 10.1126/science.6177036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams A F, Barclay A N. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:381–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.002121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams A F. Immunol Today. 1987;8:298–303. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(87)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harpaz Y, Chothia C. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:528–539. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barclay A N, Brown M H, Law S K A, McKnight A J, Tomlinson M G, van der Merwe P A. Leucocyte Antigens Facts Book. 2nd Ed. London: Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal A, Eastman Q M, Schatz D G. Nature (London) 1998;394:744–751. doi: 10.1038/29457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis S J, Ikemizu S, Wild M K, van der Merwe P A. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:217–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry J, Miller M M, Pontarotti P. Immunol Today. 1999;20:285–288. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chretien I, Marcuz A, Courtet M, Katevuo K, Vainio O, Heath J K, White S J, Du Pasquier L. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4094–4104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4094::AID-IMMU4094>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsunaga T, Rahman A. Immunol Rev. 1998;166:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]