Abstract

Background

Recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletions were recently identified with identical proximal (BP4) and distal (BP5) breakpoints and associated with mild to moderate mental retardation and epilepsy.

Methods

To further assess the clinical implications of this novel 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome, eighteen new probands with a deletion were molecularly and clinically characterised. In addition, we evaluated the characteristics of a family with a more proximal deletion between BP3 and BP4. Finally, four patients with a duplication in the BP3-BP4-BP5 region were included in this study to ascertain the clinical significance of duplications in this region.

Results

The 15q13.3 microdeletion in our series was associated with a highly variable intra- and inter-familial phenotype. At least 11 of the 18 deletions identified were inherited. Moreover, 7 of 10 siblings from four different families also had this deletion: one had a mild developmental delay, four had only learning problems during childhood, but functioned well in daily life as adults, whereas the other two had no learning problems at all. In contrast to previous findings, seizures were not a common feature in our series (only 2 of 17 living probands). Three patients with deletions had cardiac defects and deletion of the KLF13 gene, located in the critical region, may contribute to these abnormalities. The limited data from the single family with the more proximal BP3-BP4 deletion suggest this deletion may have little clinical significance. Patients with duplications of the BP3-BP4-BP5 region did not share a recognizable phenotype, but psychiatric disease was noted in 2 of 4 patients.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings broaden the phenotypic spectrum associated with 15q13.3 deletions and suggest that, in some individuals, deletion of 15q13.3 is not sufficient to cause disease. The existence of microdeletion syndromes, associated with an unpredictable and variable phenotypic outcome, will pose the clinician with diagnostic difficulties and challenge the commonly used paradigm in the diagnostic setting that aberrations inherited from a phenotypically normal parent are usually without clinical consequences.

Keywords: 15q13.3, KLF13, CHRNA7, epilepsy, cardiac

Introduction

The increased resolution of molecular karyotyping has led to the delineation of several new submicroscopic deletion and duplication syndromes [1–4]. The occurrence of these genomic disorders [5] is often mediated by low-copy repeats (LCRs) which can give rise to various genomic changes by nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR) [6]. Recently, Sharp et al. reported a novel microdeletion syndrome caused by recurrent deletions of 15q13.3 mediated by NAHR [7]. The estimated frequency of this syndrome among mentally retarded patients is 0.29%, which is comparable with the frequencies of Prader Willi syndrome (PWS), Angelman syndrome (AS) and Williams-Beuren syndrome [7].

The proximal 15q region is characterised by a high density of segmentally duplicated blocks [8–10] and therefore prone to several genomic rearrangements leading to partial aneuploidy. The breakpoints (BPs) of such rearrangements cluster in the segmentally duplicated blocks, suggesting NAHR as the mechanism of rearrangement [11]. So far, six BPs have been characterised in the chromosome 15q11q14 region [12]. Deletions between BP1-BP3 and BP2-BP3 give rise to the clinically well known syndromes of PWS and AS caused by lack of expression of imprinted genes between BP2 and BP3 [13]. Duplications of the PW/AS region (BP1-BP3), either as a result of an interstitial duplication or due to a supernumerary derivative chromosome, are associated with learning disabilities, autistic behaviour and seizures [14, 15]. In addition, larger deletions and duplications, including the PWS/AS region, extending to BP4 and BP5, have been described and result in a more extensive phenotype than the original described syndromes. [16–18]. A more distal microdeletion comprising BP5 and BP6 was described in a mentally retarded patient with cleft palate and an atrial ventricular septal defect [19].

Sharp et al. were the first to describe interstitial deletions and a duplication, comprising the BP4-BP5 region only, leading to a novel microdeletion syndrome on 15q13.3 [7]. Rearrangements in this region arise when the flanking duplicons are positioned in a direct orientation, most probably through an inversion polymorphism of the BP4-BP5 region, which generates a configuration predisposing to NAHR [10, 20]. In total, six patients with a BP4-BP5 deletion and three patients with a BP3-BP5 deletion were reported. These patients showed mild to moderate mental retardation and seven of the nine deletion cases had epilepsy and/or EEG abnormalities. Although various dysmorphisms were noted among the patients, there was no consistent or recognizable phenotype. More recently, two studies concerning microdeletions associated with schizophrenia reported the BP4-BP5 deletion in a total of 16 out of 4123 patients [21, 22]. In total, a mildly impaired cognitive function was noted in five of these patients, however, other phenotypic details were not provided. In order to determine whether there are specific clinical features commonly associated with the 15q13.3 microdeletion, further phenotypic studies in larger patient groups are necessary. To address this, we carried out molecular and clinical characterization of eighteen new probands with a deletion comprising the BP4-BP5 region and one patient with a BP3-BP4 deletion. In addition, four patients with a duplication comprising the BP4-BP5 region were included to ascertain the clinical significance of duplications in this region.

Methods

Patients and DNA samples

In this study, 19 probands with a submicroscopic deletion and four patients with submicroscopic duplications in the BP3-BP4-BP5 region at 15q13.1q13.3 were included. DNA was isolated according to standard procedures. All patients showed a normal karyotype at G-banded chromosome studies and clinical information was obtained from the referring physicians. Except for patient 10 and 15 who were referred for a congenital cardiac defect solely, all patients were referred because of development delay, and the 15q13 aberrations were found during their diagnostic work-up. Apart for patient 1 who was tested for a CHRNA7 deletion by targeted Multiplex Ligation Probe Amplification (MLPA) analysis in an ongoing study in epilepsy patients, all the submicroscopic deletions and duplications of 15q13.1q13.3 were identified with different diagnostic microarray platforms. The following array platforms were used: Patients 3 and 4: 32 k BAC array [23], patients 5 and 6: 1 Mb custom array, patients 2, 7, 8, 9 and 23: 44k Agilent array, patient 10: custom Agilent 105k array that included high-density oligonucleotide coverage of the 15q13.3 region, patient 11: Signature commercial BAC array, patients 14 and 15: 244k Agilent array, patients 12 and 17: HumanCNV370Duo from Illumina, patients 16, 18, 19 and 22: customised 4x44K Agilent oligonucleotide array [24], patients 13, 20 and 21: Affymetrix 250 Nsp SNP array. When parents and other family members were available, de novo or inherited occurrence was investigated using either Fluorescence ‘In Situ’ Hybridisation (FISH), MLPA or microarray analysis.

Molecular testing

The majority of 15q13.1q13.3 rearrangements were fine mapped using a custom high-resolution oligonucleotide array (NimbleGen Systems Inc. Madison, WI, USA) consisting of 135,000 isothermal probes (length 45–75) including 1333 probes within the chromosome 15q13 BP3-BP4-BP5 region (chr15:25,500,000 – 31,500,000, hg 18, http://genome.ucsc.edu/). DNA from patient 1 was analyzed using a custom array with 166.000 probes including 42,698 within the same 15q13 interval (NimbleGen Systems Inc. Madison, WI, USA); patient 14 was analyzed using a custom array with 72,000 probes, including 1142 probes within the same region (NimbleGen Systems Inc. Madison, WI, USA). Hybridisations were performed as described previously [25] and a single normal male control was used as a reference (GM15724, Coriell).

Synthetic MLPA probes were developed in the 15q13.1q15.1 region (27,300,000–38,500,000, hg 18, http://genome.ucsc.edu/) to test for the BP4-BP5 deletion in the family members of patient 3, 4 and 12 (except for the father of patient 4 who was not available for testing). The 10 MLPA probes were designed to 9 different genes (NDNL2, TJP1, TRPM1, KLF13, CHRNA7, GREM1 (2x), CHRM5, MEIS2, IVD) in accordance with a protocol provided by MRC-Holland (www.MRC-holland.com). Probe hybridisation and analysis was done as previously described by Schouten et al. [26]. All reagents for MLPA reaction and subsequent PCR amplification were purchased from MRC-Holland (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Results

Molecular findings

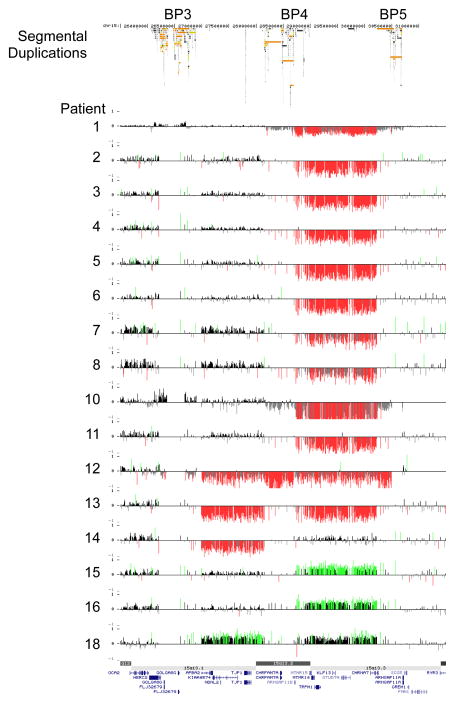

The results of the high-resolution targeted 15q13.1q13.3 array are summarized in Figure 1. Sixteen patients (cases 1–16) showed a BP4-BP5 deletion of which two were proven to be de novo, 11 were inherited (three paternally and eight maternally) and in three cases the parents were unavailable for testing. These 16 cases were found in a cohort of 6624 persons referred for idiopathic mental retardation and/or congenital abnormalities (0.24%). Two patients (cases 17 and 18) had a BP3-BP5 deletion of which one was proved to be de novo and in the second case the inheritance was unknown. One patient (case 19) had a paternally inherited BP3-BP4 deletion. Three patients (cases 20–22) had a BP4-BP5 duplication of which one was de novo and in two patients the parents were unavailable for testing. One patient (case 23) had a paternally inherited BP3-BP5 duplication.

Figure 1.

High-resolution oligonucleotide array mapping of 15q13-q13.3 rearrangements (chr 15:25.7–31.4 Mb, Hg 18). Patients 1–16 had a deletion of BP4-BP5, patients 17–18 a deletion of BP3-BP5, patient 19 a deletion of BP3-BP4, patients 20–22 a duplication of BP4-BP5 and patient 23 a duplication of BP3-BP5.

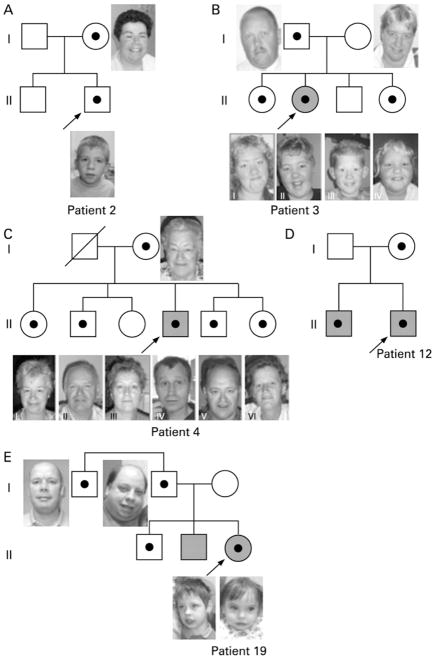

In several families with a proband with a BP4-BP5 deletion siblings were tested for this deletion. The deletion was excluded in the brother of patient 2 (Fig. 2A). In the family of patient 3 the deletion was detected in two of the three siblings, and in the relatives of patient 4 the deletion was found in four out of five siblings (Fig. 2B,C and supplementary Fig. 1.). In addition, the BP4-BP5 deletion was identified in the brother of patient 12 (Fig. 2D). In the family of patient 17 the BP3-BP4 deletion was excluded in a brother of the proband but appeared to be present in her oldest brother and a paternal uncle (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Pedigrees of families in which siblings of the proband were tested. Shaded = mental retardation. Black dot = aberration carrier.

A. Pedigree patient 2. The mother carried the same BP4-BP5 15q13.3 deletion as identified in the proband, who attends a regular primary school, with learning problems. The brother also had learning problems at primary school, however normal chromosomes.

B. Pedigree patient 3. Both sisters (II-I and II-IV) carried the same BP4-BP5 15q13.3 deletion as identified in the mild mentally retarded proband and her healthy father. The deletion was not found in the healthy mother and brother (II-III). Both sisters had had learning problems for which they attended a period of special schooling, however both had continued regular schooling.

C. Pedigree patient 4. Except for female II-III, all sibs carried the same BP4-BP5 15q13.3 deletion as identified in the mentally retarded proband and his healthy mother. Female II-I and male II-V both had had learning problems in childhood but both showed normal adaptive skills in adulthood. The remaining siblings (II-II, II-III and II-VI) never had had learning problems and finished normal primary and secondary school.

D. Pedigree patient 12. Both brothers had a mild developmental delay and both carried the BP4-BP5 15q13.3 deletion. The mother was not formally assessed but she appeared to have a borderline level of intelligence.

E. Pedigree patient 18. Father and daughter both have a BP3-BP4 deletion. The same deletion was also identified in her oldest brother and paternal uncle who both had had normal development. Her mentally retarded brother was also tested, but did not have the deletion.

In addition to the de novo 15q13.3 deletion in patient 13, a 700 kb maternally inherited duplication on 22q11.21q11.22 was detected. Besides the BP3-BP5 duplication in patient 23, a 200 kb deletion at 14q31.1 was identified. Both the BP3-BP5 duplication and the 14q31.1 deletion were also present in her father.

Clinical data

All 23 patients are described in more clinical detail in the section below. The clinical features of all deletion (n=19) and duplication (n=4) patients are summarized in tables 1 and 2 respectively. Photographs of patients are shown in those cases where parents consented for publication.

Table 1.

Clinical features of all probands with a 15q13 deletion. Patients 1–15 (BP4-BP5), patients 16–17 (BP3-BP5) and patient 18 (BP3-BP4).

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | Patient 10 | Patient 11 | Patient 12 | Patient 13 | Patient 14 | Patient 15 | Patient 16 | Patient 17 | Patient 18 | Patient 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP3BP5 | BP3BP5 | BP3BP4 |

| Gender | female | male | female | male | male | female | male | female | female | female | female | male | female | male | female | female | male | male | female |

| Age | 26 years | 5 years, 6 months | 14 years | 44 years | 6 years, 10 months | 28 years | 4 years | 1 year, 6 months | 2 years, 8 months | 9 years | 4 years, 9 months | 13 years | 4 years | 5 years | Fetus 18 weeks gestation | 3 yrs 6 mo | 17 years | 8 years | 2years 4months |

| Inheritance | inherited mat | inherited mat | inherited pat | inherited mat | de novo | inherited pat | inherited mat | NA | NA | NA | inherited pat | inherited mat | de novo | unknown | inherited | inherited mat | de novo mat | NA | inherited pat |

| Mental retardation | severe | learning problems | mild | moderate | severe | learning problems | severe | moderate | mild-moderate | normal intelligence | mild | moderate | mild | mild | moderate | mild | moderate | moderate | |

| Epilepsy/abnormal EEG | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Hypotonia | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | ||

| Birth weight | P25 | >P97 | P50 | P20 | P50 | P95 | P84 | P50 | <P3 | NA | P95 | NA | P15 | P50 | NA | NA | P3-P98 | NA | < P3 |

| Height | < P3 | P91 | P20 | <P3 | P3-P98 | P98 | P50 | P10 | P84 | NA | P45 | P10 | NA | P3 | NA | P95 | P3-P10 | P10 | < P3 |

| OFC | < P3 | >P95 | P30 | P7 | >P97 | P75 | P90 | P10 | P75 | NA | P50 | P3-P25 | P10 | P10 | NA | P60 | P3 | P60 | < P3 |

| Behaviour problems | aggressive behaviour in childhood, apathetic behaviour at adult age | poor attention span | temper tantrums impulsive behaviour poor attention span | aggressive behaviour impulsive behaviour |

autistic behaviour | obsessive behaviour, easy upset, hypersensitive to sounds and crowds | anxious and claiming behaviour | poor concentration span | poor concentration span | hyperactive behaviour | poor concentration span | ||||||||

| Other features | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cranial | plagiocephaly bitemporal narrowing |

long face and forehead | large forehead | ||||||||||||||||

| Ears | folded helices | large ears | large ears | large low-set ears | low-set, cup shaped ears | low set, prominent ears overfolded helices | large ears | impaired hearing | |||||||||||

| Ocular region | strabismus blepharophimosis synophrys |

S-shaped uper eyelids full eyebrows |

strabismus | retinal dystrophy, myopia | strabismus | down slant palp fissures | full eyebrows synophyrys |

hypertelorism synophrys |

downslant palp fissures lack of eyelashes medial third arched eyebrows |

upslant palp fissures hypotelorism synophrys |

down slant palp fissures arched eyebrows long eye lashes |

upslant palp fissures hypertelorism |

|||||||

| Nose | bulbous nasal tip | fleshy nose | full nasal tip | narrow nasal bridge, pointed tip | upwards position of nares | bulbous nose | broad nasal tip | short upturned nose | large nose | prominent nasal root | |||||||||

| Mouth area | smooth philtrum grooved chin |

pouting lower lip, prognathia oligo- hypodontia |

thin upper lip large mouth |

thin upper lip, broad mouth smooth philtrum |

smooth philtrum | large mouth | |||||||||||||

| Extremities | tapered fingers deep palmar creases 4th and 5th toes hypoplasia |

clinodactyly 5th fingers | patella luxation | genu valgum | clinodactyly fifth fingers | simian crease bilaterally | syndactyly 2nd-3rd toes | fainted distal finger creases broad first toes, sandal gap |

clinodactyly 5th fingers brachydactyly |

broad fingertips | brachydactyly | ||||||||

| Spine | scoliosis spina bifida occulta S1 |

scoliosis | |||||||||||||||||

| Heart | Fallot tetralogy | AVSD, coarctatio aortae hypoplastic aortic arch patent ductus arteriosus |

cardiac hypoplasia tricuspid stenosis |

mitral valvae prolaps slightly enlarged left ventricle |

|||||||||||||||

| Skin | pigmented naevi | pigmented naevi | café au lait spots | dry skin | pigmented naevi | ||||||||||||||

| Brain MRI/CT | arachnoidal cyst parenchymal hypoplasia dilated ventricles corpus callosum hypogenesis |

NA | NA | NA | white matter anomalies periventricular changes |

NA | neonatal ultrasound normal MRI/CT NA |

NA | normal | NA | normal | normal | NA | enlarged subarachnoideal space | Fetal necropsy normal | NA | normal | NA | NA |

AVSD = atrial ventricular septal defect, NA = information not available

Table 2.

Clinical features of all probands with a 15q13 duplication. Patient 19–21 (BP4-BP5) and patient 22 (BP3-BP5).

| Patient 20 | Patient 21 | Patient 22 | Patient 23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplication | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP4BP5 | BP3BP5 |

| Gender | male | female | female | female |

| Age | 17 years | 4 years, 6 months | 20 years | 4 years, 10 months |

| Inheritance | NA | de novo | NA | inherited pat |

| Mental retardation | mild | mild | mild-moderate | severe |

| Epilepsy/abnormal EEG | − | − | − | − |

| Hypotonia | + | − | + | + |

| Birth weight | P50 | >p98 | NA | P3-P98 |

| Height | P30 | P50 | P3 | P25 |

| OFC | P60 | P45 | P60 | P50 |

| Current weight | NA | > P98 | NA | > P98 |

| Behaviour problems | autistic features bipolar disorder | − | preoccupation with food extremely talkative | autistic features |

| Other features | ||||

| Ocular region | synophrys | hypertelorism | slightly deep-set eyes | |

| Nose | High nasal bridge | |||

| Ears | Low set ears Recurrent ear infections |

Low set ears Recurrent ear infections |

||

| Extremities | Cut. syndactlyly fingers Brachydactyly Cut. syndactyly 2–3 toes |

Single palmar crease | ||

| Abdomen/urogenital | Cryptorchid testes | Inverted nipples | ||

| Brain MRI/CT | normal | normal | NA | normal |

Deletion cases

Patient 1

This female (Fig. 3A) was the first child of non-consanguineous parents and born after an uncomplicated pregnancy with a weight of 2,960 g (25th centile). At the age of 1 month seizures started. She could walk at the age of 22 months and she pronounced her first words at 4 years. She showed aggressive behaviour in infancy. At adult age she was severely mentally retarded and speech was restricted to few repetitive sentences. She showed apathetic behaviour, epilepsy and had sleeping problems. She had a short stature of 147.5 cm (< 3rd centile) and microcephaly with an OFC of 51cm (< 3rd centile). At clinical examination she presented with an asymmetric skull with bitemporal narrowing, bristly hair, synophrys, blepharophimosis, squint, a bulbous nasal tip and folded helices. Furthermore, she had tapering fingers, deep palmar creases, hypoplastic 4th and 5th toes, an external rotation of the feet and multiple pigmented naevi. An MRI of the brain, at 26 years of age, showed several abnormalities consisting of an arachnoidal cyst, parenchymal hypoplasia, subcerebellar picking with dislocation of parenchymal structures, lateral ventricle dilatation and a mild corpus callosum hypogenesis. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion, which was also present in the normal mother. Family history revealed a sister in good health and a 2nd grade cousin of maternal lineage reported with autism.

Figure 3. Probands with a deletion comprising BP4-BP5.

Photographs of probands with a deletion of BP4-BP5 from left to right: A. patient 1 at 26 years. B. patient 2 at 5 years and 6 months. C. patient 3 at 14 years. D. patient 4 at 40 years. E. Patient 8 at 1 year and 6 months. F. Patient 9 at the age of 2 years and 8 months. G. Patient 11 at 4 years and 9 months. H. Patient 13 at 11 years. I. patient 15 at 3.5 years of age. In addition, one patient (J.) with a deletion of BP3-BP5 at 15q13.1q13.3: patient 17 at 17 years. No recognizable facial phenotype could be established based upon the facial and further clinical appearance.

Patient 2

This boy (Fig. 3B) was born after a normal pregnancy with a weight of 4170 g (> 99th centile) at 37 weeks of gestation. Early development was normal apart from a speech delay. At 5½ years of age he attended a normal school, however with extra help because of a poor attention span (without hyperactivity) and difficulties in reading and writing. At that time he was healthy apart from asthma and he had a normal growth with a height of 120 cm (91st centile), an OFC of 55 cm (>95th centile) and a weight of 24.3 kg (50th centile). At physical examination full eyebrows, S-shaped upper eyelids, a fleshy nose and pigmented naevi were noted. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which was also present in his mother (Fig. 2A.). She had attended special school during childhood because of similar reading and writing difficulties as her son. At 35 years of age she raised two children and showed normal adaptive behaviour. She had an OFC of 57 cm (90th centile), coarse hair, a low frontal hairline, coarse hands and pigmented naevi. Her other son had similar learning problems to the proband, but did not have the BP4-BP5 deletion. Evaluation of the family history revealed a maternal uncle with learning problems.

Patient 3

This girl (Fig. 3C) was born of non consanguineous healthy parents after 42 weeks of pregnancy with a weight of 3500 g (50th centile). She was treated for a congenital hip dysplasia. After 4 years of age she developed serious behaviour difficulties with temper tantrums and sleeping problems with a disrupted day-night rhythm. At the age of 10 years she had a mild mental retardation (performance IQ:48, verbal IQ 62 and total IQ 53) and attended special schooling. At 14 years she had a height of 161 cm (20th centile), an OFC of 54 cm (30th centile) and obvious obesity. She had a hypotonic face, short palpebral fissures, epicantic folds, a full nasal tip, a small mouth and clinodactyly of the 5th fingers.

Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which was also present in the healthy father and in 2 sisters out of 3 siblings (Fig. 2B). The father had finished normal level education. Remarkably both sisters attended special school for a couple of years during the initial primary school period. However, they both continued regular schooling afterwards. They both had a flat mid-face and short palpebral fissures (like their mother) and a prominent nasal tip. In addition, the youngest sister had epicantic folds, clinodactyly of the 5th fingers and a past history of impulsive behaviour, anxiety problems and sleeping difficulties.

Patient 4

This male (Fig. 3D) was born after 39+3 weeks of gestation with a weight of 3500 g (20th centile). He showed a severe psychomotor delay: he could walk at 30 months of age but never achieved the ability to speak. In his childhood he had recurrent severe ear infections. An EEG at 14 years of age showed no abnormalities. At physical examination at the age of 44 years he was severely mentally retarded, he had a height of 168 cm (<3rd centile) and an OFC of 55 cm (7th centile). He presented with a high forehead with receding hair, strabismus convergens, a thin nasal bridge, a pointed nasal tip with the columella below the alae nasi, a grooved chin and a mild pectus excavatum.

Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion. The same deletion was present in his healthy mother and 4 of his 5 siblings (Fig. 2C and fig. 1 supplementary). The mother had attended normal schooling. Two of the 4 siblings had had learning problems in childhood and attended special schooling and the other 2 siblings had visited regular schooling. All siblings showed normal adaptive skills and 2 of them had in total 4 children of which one had visited special schooling.

Patient 5

This male was born after 40 weeks of gestation with a normal birth weight of 3425g (50th centile). Although he was born with a normal head circumference of 36 cm (50th centile) he was noted to have developed a macrocephaly with a head circumference of 54.5cm (>97centile) at 5 years and 4 months of age. He could sit at 8 months and walk at 17 months of age. At the age of 6 years and 10 months he showed an apparent speech delay, had a normal weight and height, macrocephaly, a mild hypotonia, retinal dystrophy, myopia and several café au lait spots and no obvious dysmorphisms. MRI of the brain at 1 year and 11 months of age showed diffuse changes periventricular and subcortical white matter in the left parietal and temporal regions. He was not having seizures, behavioural or sleeping problems. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 de novo deletion.

Patient 6

This female proband was born at term with a birth weight of 4050g (>97th centile). She is a member of a complex socially disadvantaged family and has two brothers and two sisters. Another two sisters died in early life, one from sudden death at 5 weeks of age and the other after complications related to seizures at 2 years of age. The proband attended special primary school and a career orientated high school during childhood. At the age of 28 years she functioned at a low normal mental level. Her stature was 182 cm (98th centile) and she had a weight of 105 kg (> 97th centile). Medical history revealed two surgeries for strabismus and patella luxation respectively. She never had seizures or behaviour problems. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which she inherited from her father.

Patient 7

This male was born after 40 weeks of gestation with a weight of 4520 g (84th centile), a length of 53 cm (50th centile) and an OFC of 38 cm (84th centile). He could sit at 18 months and walk unsupported at 3 years of age. At the age of 4 years He had a height of 105 cm (50th centile), a weight of 18 kg (65th centile) and an OFC of 54 cm (90th centile). He showed a severe mental retardation without speech development, hypotonia and aggressive and impulsive behaviour. He had low set large ears and genu valgum but showed no other apparent dysmorphisms and did not have seizures. Family history revealed mild mentally retarded parents and 6 siblings of which 2 brothers with a severe mental retardation. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which was inherited from his mother.

Patient 8

This female (fig. 3E) was prematurely born after 28 weeks of gestation with a weight of 1100 g (50th centile), a length of 36 cm (45th centile) and an OFC of 23 cm (3rd centile). Neonatal cerebral ultrasound was normal. She started to sit unsupported at 12 months post term date and showed a delay in speech development. At 1 year and 6 months she showed a moderate developmental delay and had a length of 75.5 cm, an OFC of 44.5 cm (both 10th centile corrected for prematurity) and a weight of 9290 g (40th centile). She had downslanting palpebral fissures, ptosis, epicanthic folds, an upward position of the nares and large low set ears. Family history revealed a mild mental retardation of the father and two miscarriages. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which was maternally inherited.

Patient 9

This female (fig. 3F) was born after an uncomplicated pregnancy at 39 weeks and 6 days with a weight of 2750 g (<3rd centile) and a length of 47 cm (<3rd centile). She could walk independently at two years of age and had a delayed speech development. At the age of 2 years and 8 months she had a height of 98.5 cm (84th centile), a weight of 15.6 kg (50th centile) and an OFC of 50 cm (75th centile). She presented with a mild to moderate mental retardation and showed autistic behaviour, avoiding eye contact. An MRI of the brain was normal. She showed no obvious dysmorphisms except for a clinodactyly of both fifth fingers and a dry skin. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion of which the inheritance remained unknown.

Patient 10

This female of 9 years old presented at birth with a congenital cardiac defect consisting of a tetralogy of Fallot and a triphalangeal thumb, the latter was also present in the father. Birth and current parameters were unavailable. She showed a normal cognitive development without a history of mental delay, autism or seizures. She had no apparent dysmorphisms except for a mild hypertelorism. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion of which the inheritance remains unknown.

Patient 11

This girl (Fig. 3G) was born after 40 weeks of pregnancy complicated by polyhydramnios with a weight of 4400 g (95th centile). She could sit independently at 9 months and walk at 19 months of age. Until the age of 3 years she expressed fewer than 5 words. At 4 years and 9 months of age she showed developmental delay with fairly poor expressive language and around 60 words of vocabulary. She did not have seizures and brain MRI was normal. She has had behaviour problems consisting of obsessive cleanliness of mouth, face and hands; she is easily emotionally upset and hypersensitive with crowds and sounds. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion which she inherited from her father. He also had been delayed in walking and in speech development and attended special school during childhood. However, at adult age he spoke very well, could spell and read and showed normal adaptive behaviour and raised one child.

Patient 12

This male was born after an uncomplicated pregnancy at 42 weeks of gestation. Speech development was significantly delayed. At the age of 13 years he was moderately mentally retarded with an IQ of 49. He had no epilepsy and an MRI of the brain was normal. Cardiac and ophthalmological examination were also normal. On a skeletal survey he had a marked scoliosis and a spina bifida occulta of S1. On clinical examination he had a nasal speech, a height on the 10th centile, a weight below the 3rd centile and a head circumference between the 3rd and 25th centile. He had a long face, thick eyebrows with a synophrys, a bulbous nose and large low-set ears. The hands showed bilateral simian creases. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion that was also identified in his mother and his brother (Fig. 2D). Although his mother was not formally assessed she appeared to have a borderline level of intelligence. His brother was mentally retarded with an IQ of 50–56 at the age of 13.

Patient 13

This 11 years old daughter (Fig. 3H) of non-consanguineous parents was born at 40 weeks gestation with a weight of 2850 g (3rd centile). At birth bilateral pre-auricular tags were noted and later surgically removed. She started to walk unsupported at the age of 2.5 years. An MRI of the brain at 3.5 years of age was normal. At age 5 years she was known with a developmental delay of approximately half a year, short stature (<3rd centile) and absences. At age 7 years her IQ was estimated to be 50. At that time she visited a regular primary school, however, with difficulties for which she received extra help. An EEG at 9 years showed frontal ictal epileptic activity. At 11 years she still had a short stature (135.5 cm, <3rd centile) and a relative high weight (54 kg, 80th centile) and a normal OFC. Several dysmorphic features were noted, such as hypertelorism, blepharophimosis, a full nasal tip, a thin upper lip, clinodactyly of the 5th fingers, broad hands and feet and distal brachydactyly of fingers and toes. Furthermore, she had a nasal speech and showed normal behaviour. Microarray analysis revealed a de novo BP4-BP5 deletion.

Patient 14

This 5 years old male was born at term with a weight of 3150 g (50th centile) and a length of 49 cm (50th centile). Pregnancy was complicated with gestational diabetes. Prenatal amniocentesis showed a normal 46,XY karyotype. At the age of 18 months, the boy was first evaluated due to developmental delay, hypotonia and dysmorphic features. On MRI, an unspecific increased size of the subarachnoideal space was reported. He never had seizures. Family history was unremarkable and both parents had normal intelligence as well as his only sister of 11 years. On examination, he had a height of 102 cm (3rd centile), a weight of 15 kg (3rd centile) and an OFC of 48 cm (10th centile). He had a long face and long forehead, downslanting palpebral fissures with lack of eyelashes in the medial third, arched eyebrows, low set and protruding ears with overfolded helices, thin upper lip and a large mouth. Sloping shoulders with protruding scapulae as well as hyperlaxity were also noticed. He showed friendly behaviour and poor concentration skills. Formal IQ testing had not been performed but at 5 years of age he was functioning at about a 3,5 years level on a developmental scale for language and motor skills. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion of which the inheritance remained unknown.

Patient 15

A prenatal diagnosis of cardiac malformation was detected by fetal ultrasounds at 16 weeks gestation in an otherwise normal pregnancy and verified two weeks later as right cardiac hypoplasia with severe tricuspid stenosis. Prenatal amniocentesis showed a normal 46,XX karyotype. Pregnancy was subsequently interrupted due to the bad prognosis of the heart malformation. The fetal necropsy confirmed the cardiac findings and detected no other malformations. Both parents were apparently healthy and with normal intelligence as well as their two living children, a boy and a girl. The brother of the mother was reported to have an unspecified cardiac congenital cardiac defect but he was not available for examination. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion that was inherited from the asymptomatic mother.

Patient 16

This 3.5 years girl (Fig. 3I) was born at 34 weeks of gestation due to maternal health problems (severe asthma and bronchiectasis). After birth she was found to have a pneumothorax. Family history revealed a mother without educational qualifications and a father who had learning problems. Furthermore, she had a brother, who was diagnosed with epilepsy, but had a normal development. A maternal sister attended special school during childhood and two of her three children were visiting special school. At 3.5 years she had a moderate to severe developmental delay, a poor concentration and behavioural problems. She had a height of 113.5 cm (91–98th centile), a weight of 17 Kg (75th – 90th centile), and an OFC of 51.1cm (50th –75th centile), curly blond hair and a large forehead. She had a broad mouth with a thin upper lip and a protuberant tongue. She had small widely spaced teeth and a smooth philtrum. Furthermore, she had fainted terminal creases on her fingers and broad big toes with a wide sandal gap. Microarray analysis showed a BP4-BP5 deletion that was inherited from the mother.

Patient 17

This boy (Fig. 3J) was born with a normal birth weight, length and OFC. He started to walk at the age of 14 months. His speech development was delayed and he was diagnosed with a mild mental retardation for which he received special schooling. The family history revealed 2 maternal half brothers, children of the grandmother, who had had learning difficulties. At the age of 13 years he presented with signs of pubertas praecox with a DHEAS level of 7.55 μmol/l and gynaecomastia. MRI of the brain at 14.5 years of age showed no abnormalities. An ultrasound of the heart showed mitral valve prolapse and the size of the left ventricle was on the upper border of normal. At the age of almost 17 years he demonstrated profound hyperactive behaviour, enuresis nocturna and apparent speech problems including dyspraxia and agrammatism. He had a weight of 83 kg (BMI=30), a height of 166 cm (between 3rd and 10th centile) and microcephaly with an OFC of 54 cm (3rd centile). At physical examination he showed mild hypotonia, obesity, upslanting palpebral fissures, a synophrys, a short nose with an upturned nasal tip, a smooth philtrum and several naevi in the neck. Furthermore he had a shawl scrotum, scoliosis, clinodactyly of the 5th fingers and brachydactyly. Microarray analysis showed a BP3-BP5 deletion which was proven to have occurred de novo.

Patient 18

The pregnancy of this patient was complicated by premature rupture of membranes at 30 weeks of gestation. This boy was born at 35 weeks by emergency Caesarian section after failure of induction of labour which had been initiated due to poor fetal growth. After birth he was treated for minor respiratory difficulties and mild jaundice. He also had polycythaemia which resolved spontaneously. His birth weight was 2520 g (50th centile). At 20 months, he was noted to have developmental delay, hypotonia and dysmorphic features. Family history revealed a mother with mild to moderate learning difficulties. He had three siblings with the same parents, one brother with learning difficulties and two unaffected siblings. He also had one half sister with developmental delay and a half twin sibpair, less than one year old, with a possible developmental delay. The proband was fostered from an early age because his mother was unable to cope looking after her children. For this reason information on early development was scarce. At 5 ½ years of age his developmental age for gross motor and speech development was 3 ½ years. On examination, at the age of 8 years, his height was 124.7cm (25th centile), his weight was 22.1kg (9th centile) and an OFC of 53 cm (25th centile). He had long, downslanting palpebral fissures and long eyelashes, arched eyebrows, large ears and a large mouth. He had hirsutism on his back, prominent finger pads and broad finger tips, with short 5th fingers. He was generally hypotonic in his limbs. He showed friendly behaviour and sometimes had difficulties in maintaining his concentration. He had not had any seizures and a cerebral MRI or CT scan had not been performed. Microarray analysis showed a BP3-BP5 deletion of which the inheritance remained unknown.

Patient 19

This girl was born with a weight of 2250 g (< 3rd centile) at 39 weeks of gestation. The pregnancy had been complicated by intra uterine growth retardation and an elevated Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), prompting concern for spina bifida. However, fetal ultrasound showed a normal anatomy and she presented with a closed spine at birth. At 9 months she appeared to have a degree of central hypotonia and failure to thrive. At 2 years of age her weight had caught up to the 9th centile at 10.7 kg but her height remained below the 3rd centile. She was microcephalic with an OFC of 45 cm (< 3rd centile). She was functioning at approximately 16 months for her gross motor skills and other areas of development. During physical examination hypertelorism, upward slanting palpebral fissures, a prominent nasal root and brachydactyly were noted. Microarray analysis showed a BP3-BP4 deletion, which she had inherited from her father who showed a normal cognitive function. The same deletion was also confirmed in her 5 year old brother and paternal uncle, who both had had a normal development. Her other brother, aged 4, was also mentally retarded but did not have the BP3-BP4 deletion (Fig. 2E).

Duplication cases

Patient 20

This male patient was born after 36.5 weeks of gestation with a weight of 2900 g (50th centile). The family history revealed psychiatric problems in both parents, the mother had a personality disorder and recurrent depressions and the father was known with schizophrenia. During childhood he was fostered several periods when his mother was hospitalised for recurrent depressions and a borderline personality, therefore information on early childhood is minimal. CT of the brain and an EEG at 6 years of age were normal. He had recurrent ear infections and received a transplant tympanic membrane right because of cholesteatomatosa. At the age of 13 years he was operated on for a right sided undescended testis. He had a mild mental retardation and received special education both in primary and secondary school. He was known with aggressive behaviour from childhood onwards. At 17 years he was diagnosed with a bipolar disorder type II, PDD-NOS and showed autistic features. At physical examination he presented with a slender build with small shoulders and narrow thorax, height of 179.5 cm (30th centile) and an OFC of 58.2 cm (60th centile). He had a hypotonic narrow face, coarse hair with a white forelock, synophrys, apparent low set ears with folded helices and a prominent lobule, a high nasal bridge and wide-spaced teeth. Furthermore he had short fingers bilaterally with a mild cutaneous syndactyly of the 2nd, 3rd and 4th fingers. In addition, he had a partial cutaneous syndactyly of the 2nd and 3rd toes bilaterally. Microarray analysis revealed a BP4-BP5 duplication of which the occurrence could not be assessed in both parents.

Patient 21

This girl was born with a weight of 4,850 g (> 98th centile) and a length of 51 cm (50th centile). At the age of 4 years and 6 months she had a mild developmental delay. At that time she presented with a stiff way of moving, mild behaviour problems, obesity and recurrent ear infections. She had a height of 109 cm (50th centile), an OFC of 50.2 cm (45th centile) and a weight of 26.2 kg (> 98th centile). Physical examination revealed mild dysmorphic facial features consisting of brachycephaly, a broad and short forehead, low set simple formed ears with flat upper helices and hypertelorism (the latter also present in mother). Furthermore she had inverted nipples, a right-sided transverse palmar crease, flat arches of both feet, hypermobility of joints and dry skin. An MRI of the brain showed no abnormalities. Microarray analysis revealed a BP4-BP5 duplication which had occurred de novo.

Patient 22

This female patient had been in foster care since the age of 5 years. Early information was therefore not available and family history was unknown except for one sister with a normal development. During childhood she attended a special school and had severe learning difficulties. She did not have major behavioural problems but was said to have a preoccupation with food and a tendency to overeat. She was extremely talkative. At 20 years her height was 159 cm (25th centile) and an OFC of 56 cm (60th centile). She progressed through puberty normally and had normal sexual development. On examination she had slightly deep-set eyes but otherwise no apparent dysmorphisms.

Patient 23

This girl was born after an uneventful pregnancy with a normal weight, length and OFC. She showed a delayed motor development and started to walk at 19 months of age. At the age of 4 years and 10 months she had a severe mental retardation with no obvious motor problems any more. She was overweight with a weight of 24kg (>98th centile), and had a normal height of 105 cm (25th centile) and an OFC of 50cm (50th centile). MRI of the brain at the age of 2 years showed no abnormalities. She had no obvious dysmorphic features although she did not resemble her parents. She presented with distant behaviour reminiscent of autism with repetitive rocking and head banging. In addition to a BP3-BP4 duplication, a 200 kb deletion at 14q31.1 was identified in this girl. Both rearrangements were also present in her healthy father, who was of normal intelligence and appearance.

Discussion

To determine the clinical and molecular characteristics of segmental aneuploidies in the 15q13.3 region, we studied 18 newly identified probands with a deletion comprising the BP4-BP5 region (including two cases with a deletion of BP3-BP5 region), one patient with a BP3-BP4 deletion only and four new probands with a duplication comprising the BP4-BP5 region (including one case with a duplication of BP3-BP5). The 16 cases with a BP4-BP5 deletion were found in a cohort of 6624 persons with idiopathic mental retardation and congenital abnormalities (0.24%).

The deletion cases showed a broad phenotypic variability. Of the 17 living probands with a BP3-BP5 (n=2) or BP4-BP5 (n=15) deletion, sixteen had a degree of cognitive impairment varying from mild learning problems to all levels of mental retardation. Thirteen relatives carrying the deletion and one proband (case 10) functioned at a normal cognitive level: the latter was ascertained for array analysis because of tetralogy of Fallot and limb abnormalities. In the majority of patients, no significant dysmorphisms were noted. Behavioural problems were frequent in our patient cohort (10/17 probands, 59%) and mainly comprised poor attention span, hyperactivity, aggressive and impulsive behaviour (Table 1). Another common feature was hypotonia (8/17 probands, 47%) and a prominent or bulbous nasal tip (6/17 probands, 35%). Less frequently observed features were short stature (4/17 probands, 24%), strabismus (3/17 probands, 18%), large ears (4/17 probands, 24%), cardiac defects (3/18 probands, 17%), clinodactyly of the 5th fingers (4/17 probands, 24%) and pigmented naevi (3/17 probands, 18%). However, all these frequencies would be significantly lower if healthy relatives with the same deletion were included. In addition, only two patients had a history of seizures which is less frequent in our cases than those reported previously [7], and does not support the idea that seizures are a common manifestation in patients with a 15q13.3 microdeletion. Based on the phenotypic features in the individual patients in this series with a deletion including BP4-BP5, no straightforward clinically recognizable phenotype could be established (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

We identified one patient (case 18, Fig. 2E) with a deletion of BP3-BP4, which was also present in her oldest brother, father and uncle, who all had normal cognitive development, but was not present in her mentally retarded brother. A further inherited BP3-BP4 deletion was previously described in a developmentally delayed girl and her normal father [7] but not in over 2000 controls in different studies describing copy number variation in control individuals [27–36]. Based upon these numbers, the BP3-BP4 deletion appears to be a rare event which is likely to reflect the genomic architecture of this region in which there is greater homology between the inverted repeats at BP4-BP5 than BP3-BP4. The limited data so far indicate that the BP3-BP4 deletion is a novel copy number variation of doubtful clinical significance especially as the phenotype of both the BP3-BP5 cases (case 16 and 17) was not more severe affected than of patients with a deletion comprising BP4-BP5 only.

Remarkably, at least 11 of the 16 BP4-BP5 deletions were inherited. One of these parents had a mild mental retardation (mother patient 7), one appeared to have a borderline mental functioning (mother patient 12) and four had some learning difficulties as a child only (parents patients 2, 3, 11 and 16). In four different families all siblings were tested, and seven of ten siblings carried the same deletion (Fig. 2A-D). One sibling had mild developmental delay, four had learning problems in childhood, but functioned normally at a later age, and two never had learning problems at all. All, but one, parents and adult siblings showed normal adaptive function and eleven of them raised children.

In addition, in two recent studies reporting recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia, a 15q13.3 deletion was identified in seven out of 4,123 schizophrenia patients and eight out of 39,800 controls in the first study [21] and in 9 out of 3,391 patients and none of the 3,181 controls in the second [22]. The fact that we found the deletion in several normal family members of mentally retarded probands and in several controls, suggests that the BP4-BP5 deletion alone does not lead to mental retardation per se.

Therefore, we assume that the BP4-BP5 deletion plays a significant contributing role in the pathogenesis of different conditions affecting the brain, such as mental retardation and schizophrenia, in the affected individuals but the variable phenotypic outcome of the deletion is likely to be determined in conjunction with other factors. This is similar to the 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome which was initially found in patients with DiGeorge syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome predominantly [37]. However, several later studies showed that individuals, often parents of affected children, with ‘subclinical deletions’ were more common than previously considered [38–41]. The familial occurrence (parent-child) of the 22q11.2 deletion varied in different studies from 5–28 % [42–46].

Another deletion with a comparable complex inheritance pattern is the 1q21 microdeletion associated with the Thrombocytopenia Absent Radius (TAR) Syndrome [47, 48]. Although this deletion was not observed in a normal control population, approximately 75% of the TAR patients inherited the 1q21 deletion from an unaffected parent. This suggests that haploinsufficiency of the deleted region alone is not sufficient to cause TAR syndrome in the carrier parent, but is a prerequisite for the phenotype in the affected offspring. Located slightly more distal on chromosome 1q21.1, other recurrent reciprocal rearrangements have also been described. These, (most commonly 1.35 Mb deletions and duplications) result in a considerable variability in expressivity among the probands and in several cases have also been inherited from apparently unaffected parents [49].

A further, recently, described disease susceptibility locus is 16p13.1 [50]. Deletions of a 1.5 Mb segment on chromosome 16p13.1 are associated with mental retardation, microcephaly, seizures and behavioural problems. Duplications seem to predispose to autism in males. However, both aberrations show incomplete penetrance which is demonstrated by their presence in apparently unaffected relatives [51].

The 15q13.3 microdeletion is associated with a highly variable intra- and inter-familial clinical phenotype despite the uniformity of the chromosome deletion. For the 22q11.2 syndrome and other microdeletion syndromes various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the broad phenotypic spectrum also applicable to the 15q13.3 deletion. Besides the contributing contiguous genes, one other molecular mechanism might be the presence of a masked recessive mutation or functional polymorphism in one of the genes on the remaining allele, such as COMT polymorphism described in the 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome [52]. In the 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, the presence of the low activity variant, in addition to a deletion of the other allele, is a risk factor for prefrontal cortical volume decline, a lower cognition and developing psychotic symptoms [52].

Epigenetic or environmental factors are another possible explanation as suggested by discordance in clinical outcome of monozygotic twins with a 22q11.2 deletion [53, 54]. The possibility of expression differences between phenotypically diverse family members with a 15q13.3 deletion caused by an imprinting defect, such as in PWS or AS, seems unlikely since several of the BP4-BP5 deletion cases were inherited from both males and females as parents of origin (two paternal, five maternal). Moreover, none of the genes in this region have been described to possess imprinting characteristics (Genomic Imprinting Website: www.geneimprint.com/site/genes-by-species, September 2008).

A further explanation might be that some individuals are able to overcome one or more impairments, caused by haploinsufficiency of specific genes, during pre- or postnatal development. This is consistent with the observation that some individuals showed a normal development from birth onwards, whereas others did have some learning problems during childhood, but functioned at a normal level in adulthood. A similar mechanism had been proposed for the occurrence of the specific heart defects in 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, where reduction in penetrance during development was demonstrated in a 22q11.2 deletion mouse model [55]. As in humans, not all carrier mice show a cardiac defect at birth. However, all embryos show abnormal small fourth pharyngeal arch arteries during early embryogenesis in contrast to their wild type counterparts. Many embryos (68%) later overcome this early defect and develop normally. This ability to overcome the primary embryological defect appears to be a key factor in determining the final penetrance. We hypothesize a similar mechanism could play a role for cognitive functioning in 15q13.3 cases.

In addition, we described four patients with a duplication on 15q13.1q13.3: three cases with a duplication of the BP4-BP5 region and one patient with a BP3-BP5 duplication. Features noted in at least two out of four affected individuals in addition to the mental retardation were behavioural problems, autism, hypotonia, obesity, recurrent ear infections and low set ears. None of these patients had structural brain abnormalities or epileptic seizures. Although some dysmorphic features were noted in individual patients, these patients did not share a common recognizable phenotype (Table 2). To conclude whether this duplication is pathogenic is rather difficult with the limited number of patients (n = 4) in our cohort and the unknown inheritance of the duplication in two of them. Remarkably, the duplication was proven de novo in one of the patients, which could be interpreted as evidence of pathogenicity, but it was inherited from a normal parent in one of the other patients and two duplications in the BP3-BP4-BP5 region have been identified in a control set consisting of 960 non-retarded individuals [7]. The duplication might be a genetic modifier contributing to mental retardation and future studies of persons with 15q13 duplications are needed to determine whether there is a correlation with psychiatric disease and cognitive functioning in these patients.

There are six known genes (Fig. 1) within the BP4-BP5 region (29.0–30.5 Mb, hg 18), any or all of which may contribute to the phenotypes observed in patients with deletions. The CHRNA7 gene encodes a synaptic ion channel protein mediating neuronal signal transmission. It has been suggested that the CHRNA7 gene is an interesting candidate gene in the pathogenesis of epilepsy [56, 57], but the frequency of epilepsy in our cohort probands was relatively low (12 %). If all BP4-BP5 carriers (probands and relatives) are considered the frequency becomes even lower (6 %). Interestingly, several patients with a deletion showed apparent behavioural problems such as aggressive and impulsive behaviour, autism, short attention span and hyperactivity. Moreover, in two patients with a duplication, clear psychiatric disease was reported: one patient presented with autistic features and bipolar disorder and another patient showed autistic behaviour and self-mutilation. Interestingly, patients with supernumerary marker(15) chromosomes frequently show autistic behaviour. Although these duplications are often confined to the PWS/AS region (BP1-BP3), patients with larger markers including BP4 and BP5 have been described [58–60]. Different studies have shown linkage of markers in the proximity of the CHRNA7 gene with schizophrenia, with an endophenotype of schizophrenia (the P50 sensory gating disorder) and with bipolar disorder [61–63]. However, these findings were not consistently replicated [64, 65]. Recently BP4-BP5 deletions have been described in sixteen individuals with schizophrenia, one of whom also had autism [21–22]. This association with psychiatric disease suggests an even broader developmental impact of the BP4-BP5 deletion than previously recognised. Remarkably, none of our deletion carriers, probands and relatives, had schizophrenia although one patient had autism and several cases showed apparent behaviour problems. Neither of the two schizophrenia studies discusses whether duplications of the same region have been found in these individuals. In our series, one duplication case with bipolar disorder, a disease closely related to schizophrenia, had a father with schizophrenia who was unfortunately unavailable for testing. In order to establish a possible relationship of duplications in this region with psychiatric disorders further studies will be necessary.

Cardiac defects were noted in three deletion patients (18%), one patient with mitral valve prolapse and a slightly enlarged left ventricle, one patient with tetralogy of Fallot and a fetal case with right cardiac hypoplasia with severe tricuspid stenosis. Interestingly, one of the genes within the BP4-BP5 region is KLF13 (Kruppel-Like transcription Factor 13) encoding a member of the Kruppel-like family of zinc-finger proteins that was recently identified as a regulator of cardiac gene expression and heart morphogenesis [66]. KLF13 is a well-conserved gene and a functional knockdown of KLF13 in Xenopus embryos results in a cardiac phenotype. In these embryos initial heart development was normal but, 5 days post-fertilisation, the heart was visibly smaller and histological examination of the KLF13-depleted hearts showed several defects including a lack of ventricular trabeculation, atrial septal defects, delayed atrioventricular cushion formation and maturation of valves [67] [67]. We suggest that the finding of a 15q13.3 deletion, comprising the KLF13 gene, in a patient should warrant further cardiac evaluation.

In conclusion, the clinical significance of the 15q13.3 microduplication remains uncertain, although it may be associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric disease. The 15q13.3 microdeletion does not lead to an as yet clinically recognizable syndrome but comprises an extensive clinical spectrum ranging from normal development, to learning problems, to mild and even severe mental retardation and may also predispose to psychiatric disease. The existence of microdeletions, associated with an unpredictable and variable phenotypic outcome, will pose the clinician with diagnostic difficulties and will challenge us to re-evaluate the commonly used paradigm in the diagnostic setting, that aberrations inherited from a phenotypically normal parent are usually non-pathogenic.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the parents and children who have participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge Gaby van de Ven-Schobers for her assistance, Dr. Elham Sadighi Akha, Ms Julie Evans and Dr Anneke Seller for sample processing. This work was supported by grants from the European commission: AnEUploidy project (LSHG-CT-2006-037627) under FP6, and grant agreement 21950 to A.J.S. under FP7 and supplemental grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW 907-00-058, ZonMW 917-86-319 to B.B.A.d.V, ZonMW 920-03-338 to D.A.K), Hersenstichting Nederland (B.B.A.d.V.). A.K. was supported by research grant 7617 from the Estonian Science Foundation. S.J.L.K. is supported by the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre with funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme; the views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. E.E.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

“Written consent of the patients (or his/her legal guardian) for publication of their images in print and online was received.”

“The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Journal of Medical Genetics and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://JMG.bmjjournals.com/misc/ifora/licenceform.shtml).”

Reference List

- 1.Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Pfundt R, de LN, Knight SJ, Regan R, Kooy RF, Reyniers E, Romano C, Fichera M, Schinzel A, Baumer A, Anderlid BM, Schoumans J, Knoers NV, van Kessel AG, Sistermans EA, Veltman JA, Brunner HG, de Vries BB. A new chromosome 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome associated with a common inversion polymorphism. Nat Genet. 2006 Sep;38(9):999–1001. doi: 10.1038/ng1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharp AJ, Selzer RR, Veltman JA, Gimelli S, Gimelli G, Striano P, Coppola A, Regan R, Price SM, Knoers NV, Eis PS, Brunner HG, Hennekam RC, Knight SJ, de Vries BB, Zuffardi O, Eichler EE. Characterization of a recurrent 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007 Mar 1;16(5):567–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willatt L, Cox J, Barber J, Cabanas ED, Collins A, Donnai D, FitzPatrick DR, Maher E, Martin H, Parnau J, Pindar L, Ramsay J, Shaw-Smith C, Sistermans EA, Tettenborn M, Trump D, de Vries BB, Walker K, Raymond FL. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization of a new syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005 Jul;77(1):154–60. doi: 10.1086/431653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensenauer RE, Adeyinka A, Flynn HC, Michels VV, Lindor NM, Dawson DB, Thorland EC, Lorentz CP, Goldstein JL, McDonald MT, Smith WE, Simon-Fayard E, Alexander AA, Kulharya AS, Ketterling RP, Clark RD, Jalal SM. Microduplication 22q11.2, an emerging syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular analysis of thirteen patients. Am J Hum Genet. 2003 Nov;73(5):1027–40. doi: 10.1086/378818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998 Oct;14(10):417–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupski JR, Stankiewicz P. Genomic disorders: molecular mechanisms for rearrangements and conveyed phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2005 Dec;1(6):e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, Baker C, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Schroer RJ, Novara F, De GM, Ciccone R, Broomer A, Casuga I, Wang Y, Xiao C, Barbacioru C, Gimelli G, Bernardina BD, Torniero C, Giorda R, Regan R, Murday V, Mansour S, Fichera M, Castiglia L, Failla P, Ventura M, Jiang Z, Cooper GM, Knight SJ, Romano C, Zuffardi O, Chen C, Schwartz CE, Eichler EE. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet. 2008 Mar;40(3):322–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Eichler EE. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002 Aug 9;297(5583):1003–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zody MC, Garber M, Sharpe T, Young SK, Rowen L, O’Neill K, Whittaker CA, Kamal M, Chang JL, Cuomo CA, Dewar K, FitzGerald MG, Kodira CD, Madan A, Qin S, Yang X, Abbasi N, Abouelleil A, Arachchi HM, Baradarani L, Birditt B, Bloom S, Bloom T, Borowsky ML, Burke J, Butler J, Cook A, DeArellano K, DeCaprio D, Dorris L, III, Dors M, Eichler EE, Engels R, Fahey J, Fleetwood P, Friedman C, Gearin G, Hall JL, Hensley G, Johnson E, Jones C, Kamat A, Kaur A, Locke DP, Madan A, Munson G, Jaffe DB, Lui A, Macdonald P, Mauceli E, Naylor JW, Nesbitt R, Nicol R, O’Leary SB, Ratcliffe A, Rounsley S, She X, Sneddon KM, Stewart S, Sougnez C, Stone SM, Topham K, Vincent D, Wang S, Zimmer AR, Birren BW, Hood L, Lander ES, Nusbaum C. Analysis of the DNA sequence and duplication history of human chromosome 15. Nature. 2006 Mar 30;440(7084):671–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makoff AJ, Flomen RH. Detailed analysis of 15q11-q14 sequence corrects errors and gaps in the public access sequence to fully reveal large segmental duplications at breakpoints for Prader-Willi, Angelman, and inv dup(15) syndromes. Genome Biol. 2007;8(6):R114. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pujana MA, Nadal M, Guitart M, Armengol L, Gratacos M, Estivill X. Human chromosome 15q11-q14 regions of rearrangements contain clusters of LCR15 duplicons. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002 Jan;10(1):26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mignon-Ravix C, Depetris D, Luciani JJ, Cuoco C, Krajewska-Walasek M, Missirian C, Collignon P, Delobel B, Croquette MF, Moncla A, Kroisel PM, Mattei MG. Recurrent rearrangements in the proximal 15q11-q14 region: a new breakpoint cluster specific to unbalanced translocations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007 Apr;15(4):432–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassidy SB, Dykens E, Williams CA. Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: sister imprinted disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97(2):136–46. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200022)97:2<136::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook EH, Jr, Lindgren V, Leventhal BL, Courchesne R, Lincoln A, Shulman C, Lord C, Courchesne E. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Apr;60(4):928–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennis NR, Veltman MW, Thompson R, Craig E, Bolton PF, Thomas NS. Clinical findings in 33 subjects with large supernumerary marker(15) chromosomes and 3 subjects with triplication of 15q11-q13. Am J Med Genet A. 2006 Mar 1;140(5):434–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahoo T, Bacino CA, German JR, Shaw CA, Bird LM, Kimonis V, Anselm I, Waisbren S, Beaudet AL, Peters SU. Identification of novel deletions of 15q11q13 in Angelman syndrome by array-CGH: molecular characterization and genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007 Sep;15(9):943–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang NJ, Liu D, Parokonny AS, Schanen NC. High-resolution molecular characterization of 15q11-q13 rearrangements by array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) with detection of gene dosage. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Aug;75(2):267–81. doi: 10.1086/422854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calounova G, Hedvicakova P, Silhanova E, Kreckova G, Sedlacek Z. Molecular and clinical characterization of two patients with Prader-Willi syndrome and atypical deletions of proximal chromosome 15q. Am J Med Genet A. 2008 Aug 1;146A(15):1955–62. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdogan F, Ullmann R, Chen W, Schubert M, Adolph S, Hultschig C, Kalscheuer V, Ropers HH, Spaich C, Tzschach A. Characterization of a 5.3 Mb deletion in 15q14 by comparative genomic hybridization using a whole genome “tiling path” BAC array in a girl with heart defect, cleft palate, and developmental delay. Am J Med Genet A. 2007 Jan 15;143(2):172–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, Baker C, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Schroer RJ, Novara F, De GM, Ciccone R, Broomer A, Casuga I, Wang Y, Xiao C, Barbacioru C, Gimelli G, Bernardina BD, Torniero C, Giorda R, Regan R, Murday V, Mansour S, Fichera M, Castiglia L, Failla P, Ventura M, Jiang Z, Cooper GM, Knight SJ, Romano C, Zuffardi O, Chen C, Schwartz CE, Eichler EE. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet. 2008 Mar;40(3):322–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefansson H, Rujescu D, Cichon S, Pietilainen OP, Ingason A, Steinberg S, Fossdal R, Sigurdsson E, Sigmundsson T, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Hansen T, Jakobsen KD, Muglia P, Francks C, Matthews PM, Gylfason A, Halldorsson BV, Gudbjartsson D, Thorgeirsson TE, Sigurdsson A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Bjornsson A, Mattiasdottir S, Blondal T, Haraldsson M, Magnusdottir BB, Giegling I, Moller HJ, Hartmann A, Shianna KV, Ge D, Need AC, Crombie C, Fraser G, Walker N, Lonnqvist J, Suvisaari J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Paunio T, Toulopoulou T, Bramon E, Di FM, Murray R, Ruggeri M, Vassos E, Tosato S, Walshe M, Li T, Vasilescu C, Muhleisen TW, Wang AG, Ullum H, Djurovic S, Melle I, Olesen J, Kiemeney LA, Franke B, Kahn RS, Linszen D, van OJ, Wiersma D, Bruggeman R, Cahn W, Germeys I, de HL, Krabbendam L, Sabatti C, Freimer NB, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Andreassen OA, Ophoff RA, Georgi A, Rietschel M, Werge T, Petursson H, Goldstein DB, Nothen MM, Peltonen L, Collier DA, St CD, Stefansson K. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008 Jul 30; doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone JL, O’Donovan MC, Gurling H, Kirov GK, Blackwood DH, Corvin A, Craddock NJ, Gill M, Hultman CM, Lichtenstein P, McQuillin A, Pato CN, Ruderfer DM, Owen MJ, St CD, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, Purcell Leader SM, Stone JL, Ruderfer DM, Korn J, Kirov GK, Macgregor S, McQuillin A, Morris DW, O’Dushlaine CT, Daly MJ, Visscher PM, Holmans PA, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, Purcell Leader SM, Gurling H, Corvin A, Blackwood DH, Craddock NJ, Gill M, Hultman CM, Kirov GK, Lichtenstein P, McQuillin A, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Pato CN, Purcell SM, Scolnick EM, St CD, Stone JL, Sullivan PF, Sklar LP, O’Donovan MC, Kirov GK, Craddock NJ, Holmans PA, Williams NM, Georgieva L, Nikolov I, Norton N, Williams H, Toncheva D, Milanova V, Owen MJ, Hultman CM, Lichtenstein P, Thelander EF, Sullivan P, Morris DW, O’Dushlaine CT, Kenny E, Waddington JL, Gill M, Corvin A, McQuillin A, Choudhury K, Datta S, Pimm J, Thirumalai S, Puri V, Krasucki R, Lawrence J, Quested D, Bass N, Curtis D, Gurling H, Crombie C, Fraser G, Leh KS, Walker N, St CD, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ, McGhee KA, Pickard B, Malloy P, Maclean AW, Van BM, Visscher PM, Macgregor S, Pato MT, Medeiros H, Middleton F, Carvalho C, Morley C, Fanous A, Conti D, Knowles JA, Paz FC, Macedo A, Helena AM, Pato CN, Stone JL, Ruderfer DM, Korn J, McCarroll SA, Daly M, Purcell SM, Sklar P, Purcell SM, Stone JL, Chambert K, Ruderfer DM, Korn J, McCarroll SA, Gates C, Gabriel SB, Mahon S, Ardlie K, Daly MJ, Scolnick EM, Sklar P. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008 Jul 30; doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries BB, Pfundt R, Leisink M, Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Janssen IM, Reijmersdal S, Nillesen WM, Huys EH, Leeuw N, Smeets D, Sistermans EA, Feuth T, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM, van Kessel AG, Schoenmakers EF, Brunner HG, Veltman JA. Diagnostic genome profiling in mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005 Oct;77(4):606–16. doi: 10.1086/491719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber JC, Maloney VK, Huang S, Bunyan DJ, Cresswell L, Kinning E, Benson A, Cheetham T, Wyllie J, Lynch SA, Zwolinski S, Prescott L, Crow Y, Morgan R, Hobson E. 8p23.1 duplication syndrome; a novel genomic condition with unexpected complexity revealed by array CGH. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008 Jan;16(1):18–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharp AJ, Hansen S, Selzer RR, Cheng Z, Regan R, Hurst JA, Stewart H, Price SM, Blair E, Hennekam RC, Fitzpatrick CA, Segraves R, Richmond TA, Guiver C, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eis PS, Schwartz S, Knight SJ, Eichler EE. Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006 Sep;38(9):1038–42. doi: 10.1038/ng1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002 Jun 15;30(12):e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, Scherer SW, Lee C. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004 Sep;36(9):949–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locke DP, Sharp AJ, McCarroll SA, McGrath SD, Newman TL, Cheng Z, Schwartz S, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Altshuler DM, Eichler EE. Linkage disequilibrium and heritability of copy-number polymorphisms within duplicated regions of the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2006 Aug;79(2):275–90. doi: 10.1086/505653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Troge J, Alexander J, Young J, Lundin P, Maner S, Massa H, Walker M, Chi M, Navin N, Lucito R, Healy J, Hicks J, Ye K, Reiner A, Gilliam TC, Trask B, Patterson N, Zetterberg A, Wigler M. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004 Jul 23;305(5683):525–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, Pertz LM, Clark RA, Schwartz S, Segraves R, Oseroff VV, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005 Jul;77(1):78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon-Sanchez J, Scholz S, Fung HC, Matarin M, Hernandez D, Gibbs JR, Britton A, De Vrieze FW, Peckham E, Gwinn-Hardy K, Crawley A, Keen JC, Nash J, Borgaonkar D, Hardy J, Singleton A. Genome-wide SNP assay reveals structural genomic variation, extended homozygosity and cell-line induced alterations in normal individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 2007 Jan 1;16(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong KK, deLeeuw RJ, Dosanjh NS, Kimm LR, Cheng Z, Horsman DE, MacAulay C, Ng RT, Brown CJ, Eichler EE, Lam WL. A comprehensive analysis of common copy-number variations in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Jan;80(1):91–104. doi: 10.1086/510560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi N, Tsuyama N, Sasaki K, Kodaira M, Satoh Y, Kodama Y, Sugita K, Katayama H. Segmental copy-number variation observed in Japanese by array-CGH. Ann Hum Genet. 2008 Mar;72(Pt 2):193–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zogopoulos G, Ha KC, Naqib F, Moore S, Kim H, Montpetit A, Robidoux F, Laflamme P, Cotterchio M, Greenwood C, Scherer SW, Zanke B, Hudson TJ, Bader GD, Gallinger S. Germ-line DNA copy number variation frequencies in a large North American population. Hum Genet. 2007 Nov;122(3–4):345–53. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Smith AJ, Tsalenko A, Sampas N, Scheffer A, Yamada NA, Tsang P, Ben-Dor A, Yakhini Z, Ellis RJ, Bruhn L, Laderman S, Froguel P, Blakemore AI. Array CGH analysis of copy number variation identifies 1284 new genes variant in healthy white males: implications for association studies of complex diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2007 Dec 1;16(23):2783–94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Stahl TD, Sandgren J, Piotrowski A, Nord H, Andersson R, Menzel U, Bogdan A, Thuresson AC, Poplawski A, von TD, Hansson CM, Elshafie AI, Elghazali G, Imreh S, Nordenskjold M, Upadhyaya M, Komorowski J, Bruder CE, Dumanski JP. Profiling of copy number variations (CNVs) in healthy individuals from three ethnic groups using a human genome 32 K BAC-clone-based array. Hum Mutat. 2008 Mar;29(3):398–408. doi: 10.1002/humu.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donald-McGinn DM, Tonnesen MK, Laufer-Cahana A, Finucane B, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH. Phenotype of the 22q11.2 deletion in individuals identified through an affected relative: cast a wide FISHing net! Genet Med. 2001 Jan;3(1):23–9. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liling J, Cross I, Burn J, Daniel CP, Tawn EJ, Parker L. Frequency and predictive value of 22q11 deletion. J Med Genet. 1999 Oct;36(10):794–5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.36.10.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Digilio MC, Angioni A, De SM, Lombardo A, Giannotti A, Dallapiccola B, Marino B. Spectrum of clinical variability in familial deletion 22q11.2: from full manifestation to extremely mild clinical anomalies. Clin Genet. 2003 Apr;63(4):308–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, Philip N, Levy A, Seidel H, Schuffenhauer S, Oechsler H, Belohradsky B, Prieur M, Aurias A, Raymond FL, Clayton-Smith J, Hatchwell E, McKeown C, Beemer FA, Dallapiccola B, Novelli G, Hurst JA, Ignatius J, Green AJ, Winter RM, Brueton L, Brondum-Nielsen K, Scambler PJ. Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet. 1997 Oct;34(10):798–804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindsay EA. Chromosomal microdeletions: dissecting del22q11 syndrome. Nat Rev Genet. 2001 Nov;2(11):858–68. doi: 10.1038/35098574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, Philip N, Levy A, Seidel H, Schuffenhauer S, Oechsler H, Belohradsky B, Prieur M, Aurias A, Raymond FL, Clayton-Smith J, Hatchwell E, McKeown C, Beemer FA, Dallapiccola B, Novelli G, Hurst JA, Ignatius J, Green AJ, Winter RM, Brueton L, Brondum-Nielsen K, Scambler PJ. Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet. 1997 Oct;34(10):798–804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]