Abstract

Trypanosoma cruzi, the protozoan parasite responsible for Chagas' disease, causes severe myocarditis often resulting in death. Here, we report that Slamf1−/− mice, which lack the hematopoietic cell surface receptor Slamf1, are completely protected from an acute lethal parasite challenge. Cardiac damage was reduced in Slamf1−/− mice compared to wild type mice, infected with the same doses of parasites, as a result of a decrease of the number of parasites in the heart even the parasitemia was only marginally less. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments reveal that Slamf1-defIcient myeloid cells are impaired in their ability to replicate the parasite and show altered production of cytokines. Importantly, IFN-γ production in the heart of Slamf1 deficient mice was much lower than in the heart of wt mice even though the number of infiltrating dendritic cells, macrophages, CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes were comparable. Administration of an anti-Slamf1 monoclonal antibody also reduced the number of parasites and IFN-γ in the heart. These observations not only explain the reduced susceptibility to in vivo infection by the parasite, but they also suggest human Slamf1 as a potential target for therapeutic target against T. cruzi infection.

Author Summary

Chagas' disease caused by the intracellular protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi is the most important parasitic infection in Latin America affecting several million persons. Nonetheless, there is no therapy or vaccine available. Thus, more efforts are needed to identify new therapeutic targets. Here, we report that Slamf1, which controls phagosomal/lysosomal fusion and phagosomal NADPH-oxidase activity, is required for T.cruzi replication in macrophages and dendritic cells, but not in other cells, which do not express the receptor. In the absence of Slamf1 we detect reduced number of parasites in the heart compared to infected wt mice. This explains why T. cruzi-infected Slamf1 deficient mice do not succumb to myocarditis induced by a lethal challenge with T. cruzi in contrast to BALB/c mice. Perhaps more importantly, we demonstrate that parasite replication in phagocytes is of far greater importance for the pathogenesis of the cardiomyopathy than replication in other cells. Moreover, we found much lower IFN-γ production in the heart of Slamf1 deficient mice than in the heart of BALB/c mice. We corroborated those results using an alternative approach, blocking Slamf1 function in vivo by treating mice with anti-Slamf1 antibodies. Consequently, Slamf1 is an attractive novel therapeutic target for modulating T. cruzi infection.

Introduction

American trypanosomiasis (Chagas' disease) is caused by the intracellular protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi that is transmitted to vertebrate hosts by insect vectors belonging to the Reduviidae family [1]. It is one of the most important parasitic infection in Latin America affecting several million persons in South and Central America [2] Due to the immigration Chagas' disease is now considered an emergent one in Europe [3]. The disease is a complex zoonosis, with mammals as natural reservoir hosts. Transmission is primarily by contact with the contaminated faeces of domiciliated blood sucking triatomine bugs. The life cycle of this parasite alternates between three morphologically distinct forms: infective (metacyclic or blood trypomastigotes), insect borne (epimastigotes) which replicate in the vector and intracellular replicative (amastigotes) which grow and replicate intracellularly in a variety of mammalian cells, including macrophages, cardiomyocytes and muscle fibers [4]–[6].

Myocarditis is the most serious and frequent manifestation of acute and chronic infection [2]. The pathogenesis is thought to be triggered by parasites in the lesions and dependent on an immune-inflammatory response to them [7]–[9]. Activation of a T helper type (Th1) response, that release IFN-γ and TNF, is required to activate the microbicidal activity of macrophages important in the control of T. cruzi infection [10], [11]. Nonetheless, the development of severe cardiomyopathy in Chagas' disease is also thought to be due to a Th1-specific immune response [12].

T. cruzi infects a variety of host cells, including macrophages and cardiomyocytes. Several T. cruzi molecules, glycoproteins, trans-sialidase and mucins among others, play a role in cell invasion mainly interacting with TLRs or mannose receptors [13]–[17].

The Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule family (Slamf) receptors are adhesion molecules that are involved in signaling between immune cells regulating for instance T cell proliferation, antibody production, cytotoxic responses and cytokine production, e.g. IFNγ [18]–[25]. The self-ligand adhesion molecule Slamf1 (CD150) is not only a co-stimulatory molecule at the interface between antigen presenting cells and T cells, but also functions as a microbial sensor. For instance, Slamf1 also binds to the hemaglutinin of Measles virus and to an outer membrane protein of E.coli and S.typhimurium [26], [27]. The latter interaction drives Slamf1 into the E.coli phagosome where the receptor positively controls the microbicidal activity of macrophages by a signaling mechanism that is distinct from its signaling as an adhesion molecule [27]. Because Slamf1 partakes in bactericidal responses as the receptor and plays a role in protecting against infection with Leishmania major [23] we set out to evaluate how Slamf1-deficient mice would respond to an infection by the intracellular parasite T. cruzi. Surprisingly, we find that Slamf1−/− mice are resistant to a lethal dose of T. cruzi, because the number of parasites in the heart is greatly reduced as compared to infected wt mice. Further in vivo and in vitro experiments revealed that T. cruzi has impaired ability to replicate into Slamf1-deficient myeloid cells. Administration of an anti-Slamf1 monoclonal antibody also reduced the number of amastigotes in the heart.

Results

Slamf1−/− mice survive an acute lethal infection by T. cruzi

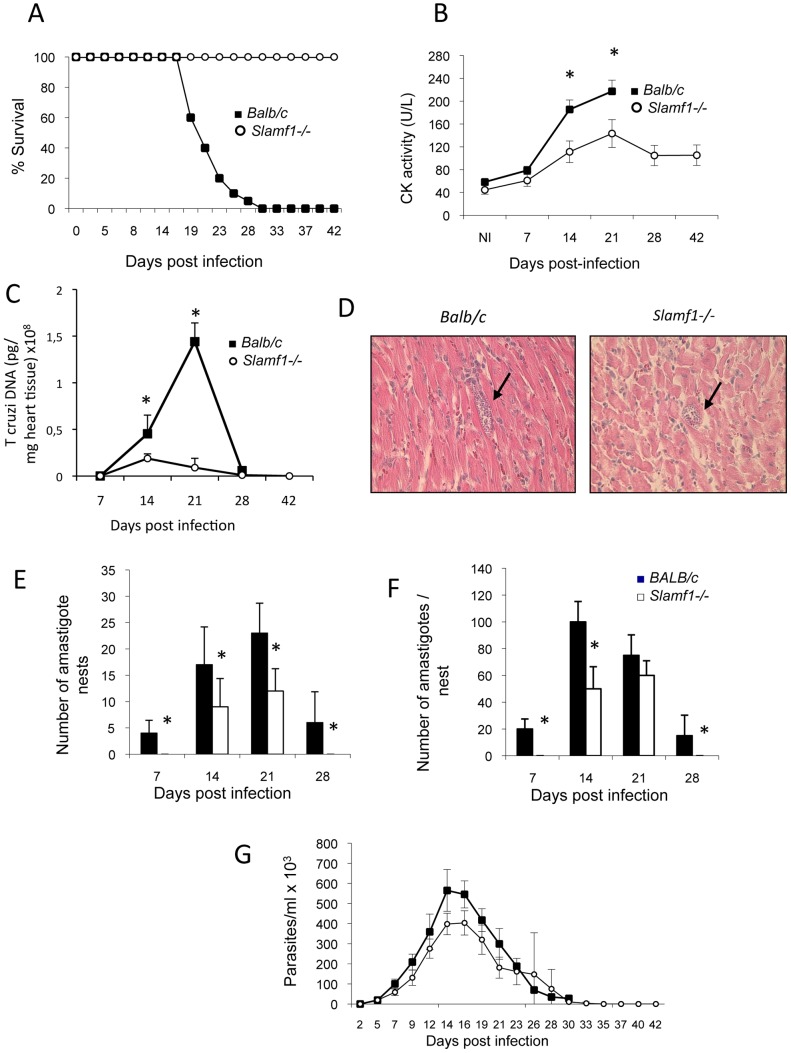

Slamf1−/− and Slamf1+/+ BALB/c mice were infected with the highly virulent T. cruzi Y strain. Interestingly, unlike wt mice, Slamf1−/− mice did not die from the infection and eventually recovered (Figure 1A). This complete resistance was observed also with a very high parasite inoculum (104 parasites/mouse) (data not shown). In the acute phase of the infection T. cruzi induces myocarditis, which is thought to be the ultimate cause of mortality [2], [9]. Indeed the creatinine kinase (CK) levels, a marker of cardiac damage, were significantly lower in the serum of infected Slamf1−/− mice than in Slamf1-sufficient BALB/c mice (Figure 1B), suggesting that reduced heart damage was the cause of the survival of the Slamf1−/− mice.

Figure 1. Time-course of T. cruzi infection in Slamf1−/− mice and reduced T. cruzi infection in the hearts from Slamf1−/− animals.

BALB/c or Slamf1−/− mice were intraperitoneally infected with 2×103 trypomastigotes of the T. cruzi Y strain and were sacrificed at different dpi. A) Survival. B) Serum CK levels. Analysis of T. cruzi presence in heart tissue from T. cruzi infected BALB/c or Slamf1−/− animals: C) Quantification of T. cruzi DNA in the heart tissue of infected BALB/c- and Slamf1−/− mice. T. cruzi DNA is expressed as the amount of parasite DNA obtained from a heart tissue sample (pg of parasite DNA/mg of heart tissue). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates of pooled DNA from 5 different mice. A representative experiment of the 3 performed is shown. D) Histochemical analysis by Hematoxylin-Eosin stain. A representative field is shown. E) Quantification of the number of amastigote nests per 20 fields. F) Average number of amastigotes/nest per 20 fields. At least 20 fields were observed of each preparation (3 preparations/mouse and 3 mice per group). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for 100 independent microscopic fields from 5 different mice (20 each). G) Blood parasitemia. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

To assess the numbers of T. cruzi present in the heart of infected wt and mutant mice, quantitative QC-PCR with parasite specific probes was used. In BALB/c mice an increase in parasite load, which follows parasitemia, peaked at 21 days postinfection (dpi). By contrast, Slamf1−/− mice had a much smaller T. cruzi load in their hearts (Figure 1C). Next, we performed histological analysis of the infected hearts and compared the numbers of T. cruzi amastigotes present in the cardiomyocytes of infected Slamf1−/− and Slamf1+/+ BALB/c mice. First, amastigote nests were less frequently observed in the hearts of Slamf1−/− than of Slamf1+/+ mice and appeared to be smaller in size (Figure 1D). Furthermore, the number of amastigote nests in Slamf1−/− mice from 7 dpi until 28 dpi was dramatically decreased compared to wt BALB/c mice (Figure 1E), although the kinetics were similar as the maximum number of amastigote nests was at 21 dpi, in close concordance with the parasite DNA levels. In addition, at all time points, the number of amastigotes per nest was lower in infected Slamf1−/− mice than in Slamf1+/+ BALB/c mice (Figure 1F). By contrast, the number of parasites in the blood followed similar kinetics in both mouse strains, although parasitemia was slightly lower than in Slamf1−/− mice than in Slamf1+/+ BALB/c mice (Figure 1G). Taken together, the data clearly demonstrate that infected Slamf1−/− mice have much less T. cruzi amastigotes in their hearts than Slamf1+/+ littermates, which is the most likely cause for the survival of Slamf1−/− mice upon an acute infection by the parasite.

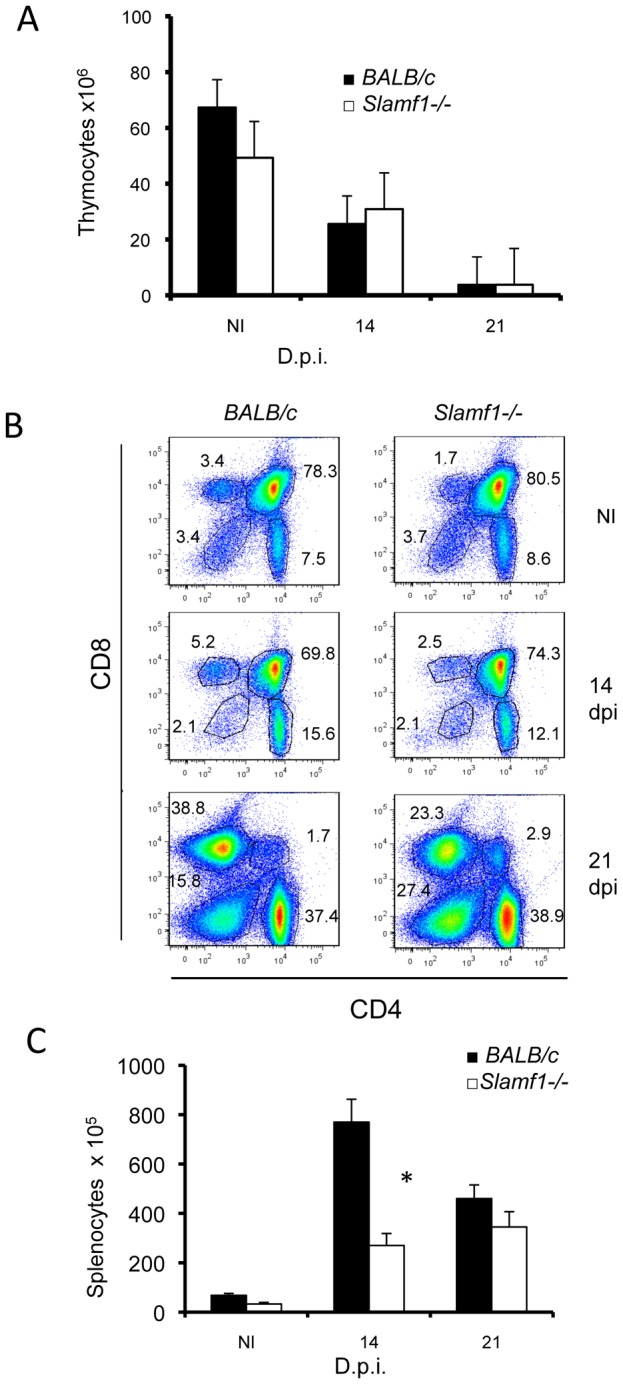

Leukocyte responses in the heart of Slamf1−/− mice infected with T.cruzi

As reported previously [28], infection of BALB/c mice with T. cruzi abrogates thymocyte development with kinetics closely following the increased numbers of circulating parasites, as judged by the loss of thymocyte numbers (Figure 2A). A reduction of the CD4+ CD8+ double positive compartment was also observed (Figure 2B), in agreement with the findings by Perez et al [29], which could be caused by TNF, corticosteroids, parasite trans-sialidase, extracellular ATP, androgens or galectin-3 [28], [29]. However, in spite of the complete survival of the Slamf1−/− mice, the kinetics of depletion of thymocyte subpopulations was identical as that in wt BALB/c mice (Figure 2B). During infection of BALB/c mice with T. cruzi splenic cellularity increased approximately 8-fold (Figure 2C) By contrast, this expansion was only 3-fold in the spleens from Slamf1−/− mice indicative of a much lesser activation state at early times although at day 21 d.p.i. cellularity increases were similar. Moreover, the distribution of leukocyte subpopulations in spleens was similar in the Slamf1−/− and wt mice (Figure S1). Taken together, the data indicate that the difference in susceptibility of Slamf1−/− and wt BALB/c mice could not be attributed to selective differences in the alterations of major leukocyte subpopulations in those organs affected by the infection.

Figure 2. Immunologic populations from lymphoid organs of T. cruzi-infected mice.

Thymocytes were isolated from thymus from control NI or T. cruzi infected BALB/c or Slamf1−/− mice at 14 and 21 dpi. A) Total number of thymocytes isolated from NI or infected mice. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates and from 5 different mice. B) CD4 and CD8 thymocytes in infected mice. Thymocytes were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry. Numbers represent % of CD4, CD8 SP, DP or DN thymocytes. Thymocytes from 5 mice in each group were pooled and analyzed. C) Spleens were isolated from infected mice and the total number of lymphocytes/spleen was quantified. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates and from 5 different mice. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

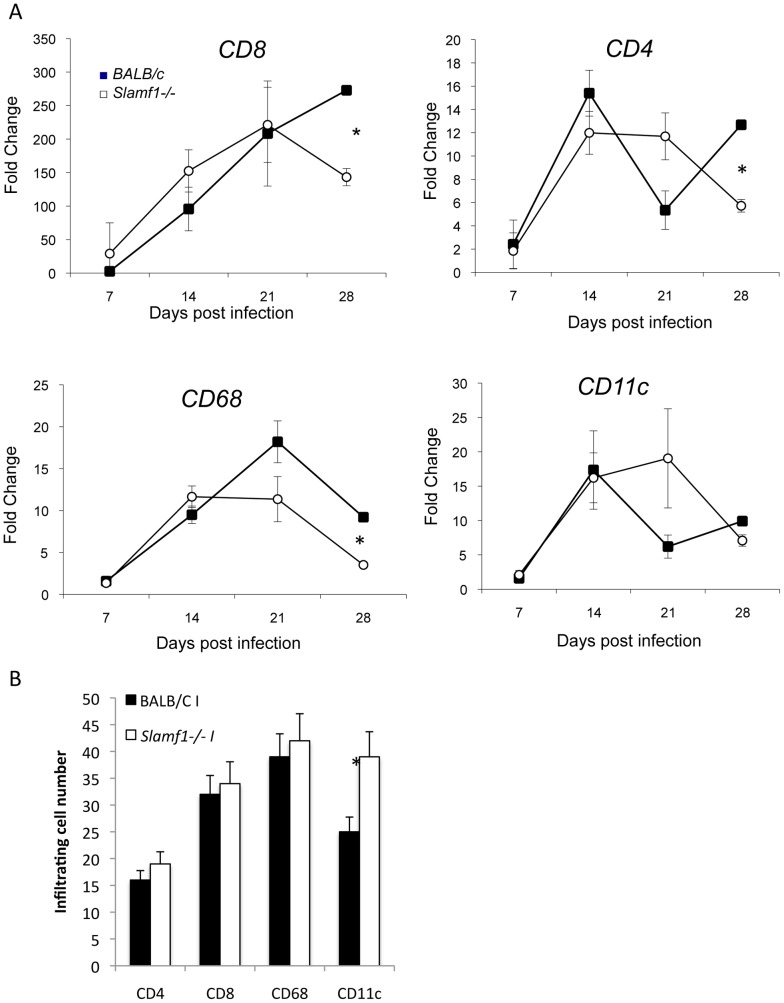

One of the key contributors to the cardiomyopathy during infection with T. cruzi is thought to be the infiltration by CD8 T lymphocytes, which as a consequence of a immune reactivity to the parasite produce an inflammatory milieu that is detrimental for heart function [8]. We therefore determined CD8 infiltration into the heart of infected mice by mRNA levels of subpopulation-specific cell surface markers [30]. CD8 infiltration increases constantly into the hearts of BALB/c mice until their death (Figure 3A). However, no significant differences were observed in the kinetic of CD8 infiltration (7 to 21 dpi) between Slamf1−/− and BALB/c mice except for a small decrease in CD8 T cell infiltration at 28 dpi, likely reflecting the resolution of infection in this strain of mice (Figure 3). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the kinetics of CD4 T lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 3A). Uninfected hearts have no detectable mRNA of those markers.

Figure 3. Heart leukocyte infiltration during T. cruzi infection.

Cell populations in mouse heart tissue during T. cruzi infection. A) Cell subset infiltration quantified by QC-PCR. Total RNA was isolated in heart tissue obtained from mice at different dpi, and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the logarithm of relative quantity (RQ) calculated from comparative threshold cycle values, as described in Material and Methods. mRNAs values are shown for DCs (CD11c), CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and macrophages (CD68). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates of pooled DNA from 3 different mice. A representative experiment of the 3 performed is shown. B) Evaluation of infiltrating subpopulations by confocal analysis. Hearts were fixed and stained with anti-CD4, CD8, CD68 and CD11 as described in Methods. Results shown are the mean number of cells (±SD) per 10 fields (20 independent microscopic fields from 3 different mice were counted). (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice BALB/c (p>0.05).

We evaluate whether myeloid cells infiltration into the heart was different between T.cruzi-infected mutant and wt mice using a similar approach. As previously shown [30], macrophage (CD68) and dendritic cell (CD11c) infiltration into the heart of wt mice infected with the parasite peaks at 21 days post-infections (Figure 3A). However, only statistically significant modest decrease in CD68+ macrophage infiltration at later times after infection (28 dpi) into the hearts of infected Slamf1−/− compared to BALB/c mice were observed. Those results were confirmed using confocal microscopy of the infected hearts with specific antibodies. No statistically significant differences in CD4, CD8 or CD68 infiltration and a slight increase in CD11c were observed at 21 dpi (Figure 3B).

Taken together, these data indicate that the striking difference in susceptibility of Slamf1−/− and wt BALB/c mice could not be attributed to differences in the recruitment of effector CD8 or CD4 T cells or myeloid cells into the heart.

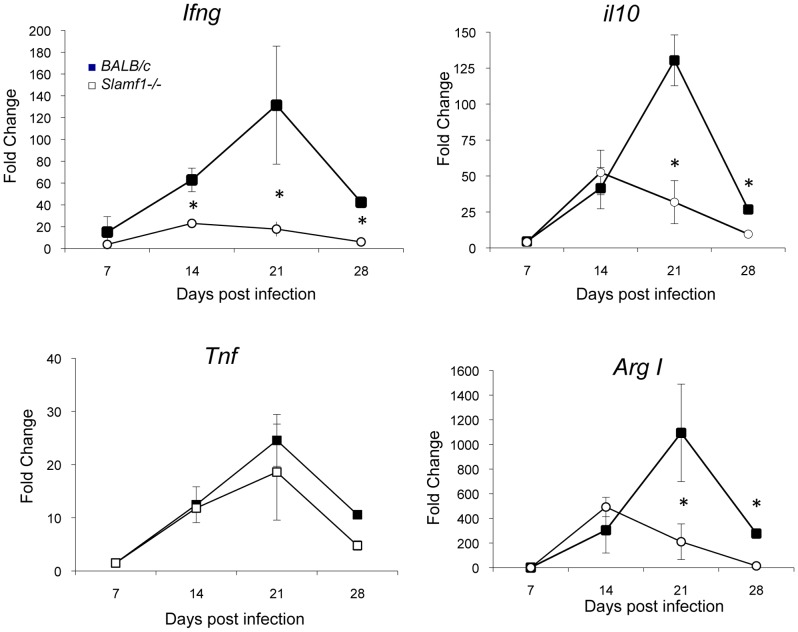

Deviation of cytokine responses in the heart of Slamf1−/− mice infected with T. cruzi

We next tested the levels of cytokines in the hearts by QC-PCR. In BALB/c mice, T. cruzi infection is accompanied by an increase in the heart of pro-inflammatory mediators TNF, IL-6 and IFNγ as well as anti-inflammatory mediators, e.g. IL-10 and arginase I [30], [31]. However, a significant reduction in IFNγ and IL-10 mRNA in the hearts of infected Slamf1−/− mice, as compared to BALB/c, was observed (Figure 4), TGF-β, IL-4 and IL-13, TNFα and IL-6 mRNA levels were no different to those in wt mice (Figure 4 and Figure S2). Interestingly, lower levels of arginase I mRNAs were also observed in Slamf1−/− mice especially at the peak of parasite load 21 dpi (Figure 4C), consistent with our previous finding that sustained arginase I expression through the acute infection is detrimental for the host [31].

Figure 4. Heart cytokine and immune modulator production by T. cruzi infected mice.

Cytokine mRNA production in the heart of T. cruzi infected mice was evaluated by QC-PCR as described in Methods. Total RNA was isolated in heart tissue obtained from BALB/c and Slamf1−/− mice at different dpi, and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the logarithm of relative quantity (RQ) calculated from comparative threshold cycle values, as described in Material and Methods. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

In contrast, systemic cytokine production detected in the sera of infected mice was not different (Figure S3), once again indicating again that changes in systemic immune responses are not responsible for the reduced susceptibility of Slamf1−/− mice to T. cruzi infection.

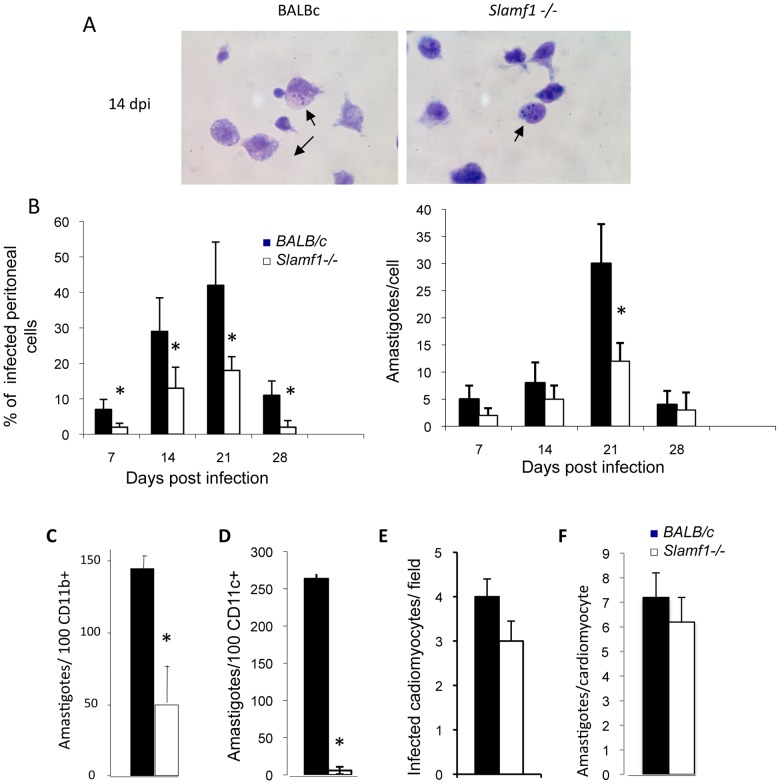

Reduced replication of T. cruzi in Slamf1−/− macrophages

An additional, and perhaps more relevant, explanation for the reduced amastigote content in the hearts of Slamf1−/− mice, could be that intracellular T. cruzi replication was impaired in the mutant mice. To address this hypothesis, we analyzed macrophages isolated from the peritoneum of mice that were infected with T. cruzi. Adherent peritoneal cells from 7 dpi to 28 dpi of infected BALB/c mice contain intracellular amastigotes, with a number that peaked at 21 dpi when approximately 50% of the peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice are infected by T. cruzi (Figure 5A and B). Those infected cells at 21 dpi contained 30 amastigotes. On average, by contrast, a maximum of only 20% of adherent cells from the peritoneal fluid of Slamf1−/− mice borne the parasite, with a maximum of 15 amastigotes/cell at 21 dpi (Figure 5B). Combining those 2 parameters, the reduction in amastigote content in peritoneal cells isolated from Slamf1−/− mice was greater than 75% as compared with wt mice. Thus, peritoneal macrophages isolated from T.cruzi infected Slamf1−/− mice appeared to replicate the parasite less efficiently.

Figure 5. Slamf1 deficient myeloid cells are less susceptible to T. cruzi infection.

Mice were intraperitoneally infected with T. cruzi and at 0, 7, 14, 21 and 28 dpi mice were sacrificed. A) Giemsa staining of adherent peritoneal macrophages from Slamf1 −/− and BALB/c animals were isolated by intraperitoneal lavage with PBS and stained. A representative field is shown. B) Quantification of infected adherent cells in the peritoneal lavages. Quantification of the number of amastigotes nests per 20 field and average number of amastigotes/nest per 20 fields. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for 100 independent microscopically fields from 5 different mice (20 each). C) Peritoneal macrophages and D) DC cells from BALB/c and Slamf1−/− mice were infected in vitro with T. cruzi (10 parasites/cell). The number of amastigotes released to the supernatant after 48 of infection was estimated by counting them by optical microscopy. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates from 3 different experiments. E and F) Neonatal cardiomyocytes were infected “in vitro” with T. cruzi and 72 h postinfection analyzed by Giemsa staining. Quantification of the number of infected cardiomyocytes per field (E) and average number of amastigotes/cardiomyocyte (F). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for 100 independent microscopic fields from 5 different mice (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

To corroborate this observation, we tested whether in vitro T. cruzi infection was impaired in isolated Slamf1−/− macrophages, dendritic cells (DC) or cardiomyocytes. Forty-eight hours after infection replication of the parasite and the generation of amastigotes was detected in wt cells (Figure 5C). However, Slamf1−/− macrophages (Figure 5C) and DCs (Figure 5D) were far less effective in supporting T. cruzi replication then wt cells. In contrast to myeloid cells, Slamf1−/− and wt cardiomyocytes were equally susceptible to in vitro infection with T. cruzi (Figure 5E and F).

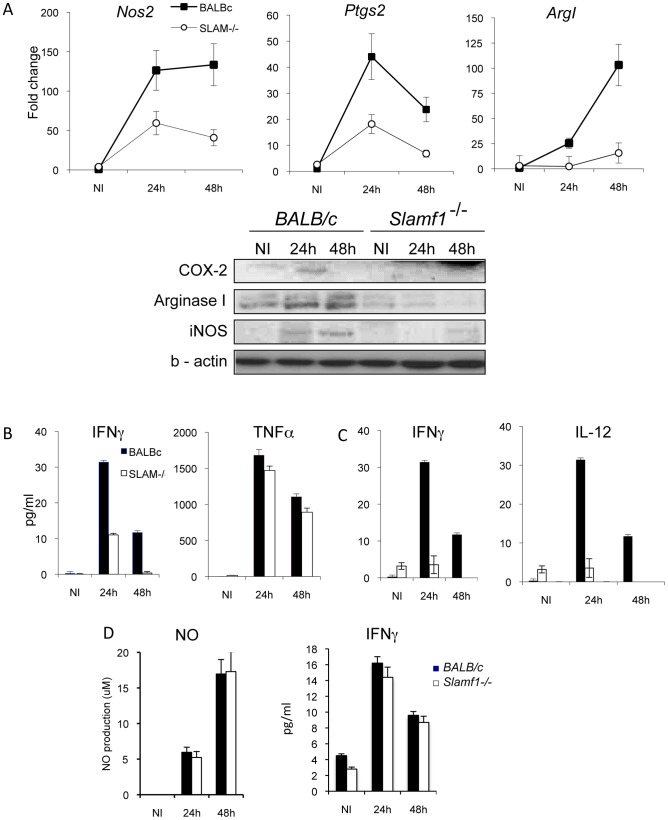

Next, we analyzed whether Slamf1 deficiency alters myeloid cell response to the parasite. As expected, T. cruzi infection of wt macrophages triggered the production of inflammatory mediators inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS Nos2) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, Ptgs2) at the mRNA and protein level (Figure 6A). Also arginase 1, Arg1, mRNA was induced upon infection. In contrast, T. cruzi infection of Slamf1−/− macrophages and show reduced levels of Ptgs2, Nos2 and Arg1 mRNAs. Moreover, infected Slamf1−/− macrophages release less IFNγ into the supernatant than infected BALB/c macrophages but similar levels of TNF (Figure 6B). Similarly, upon T. cruzi infection Slamf1−/− DC also produced less IFNγ and IL-12 than wt BALB/c DCs (Figure 6C). Not surprisingly, because cardiomyocytes do not express Slamf1, upon infection with T. cruzi these cells, whether isolated from wt or Slamf1−/− BALB/c mice, produced equal amounts of IFNγ and nitric oxide (NO) upon in vitro infection (Figure 6D). Taken together, the outcomes of these experiments support a model in which T. cruzi replication is reduced and cytokine production is altered when Slamf1 is absent in macrophages and DCs.

Figure 6. Cytokine production and immune modulators by “in vitro” T. cruzi infected DC, macrophages or cardiomyocytes.

Peritoneal macrophages, DC or cardiomyocytes from Slamf1−/− from BALB/c mice were infected in vitro with T. cruzi. A) Cox-2, iNOS and Arginase mRNA, evaluated by QC-PCR production (upper graphs) and protein by western blot (lower gels) by infected macrophages at 24 or 48 hr post infection as described in Methods. B) Cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF) release to supernatants from infected macrophages was evaluated by ELISA 24 or 48 hr post infection as described in Methods. C) Cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-12) release to supernatants from infected DCs was evaluated by ELISA 24 or 48 hr post infection as described in Methods. D) IFN-γ and NO production by infected cardiomyocytes. NO was evaluated by Gris reaction and IFN-γ by ELISA. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates from 3 different experiments. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− and BALB/c cells (p>0.05).

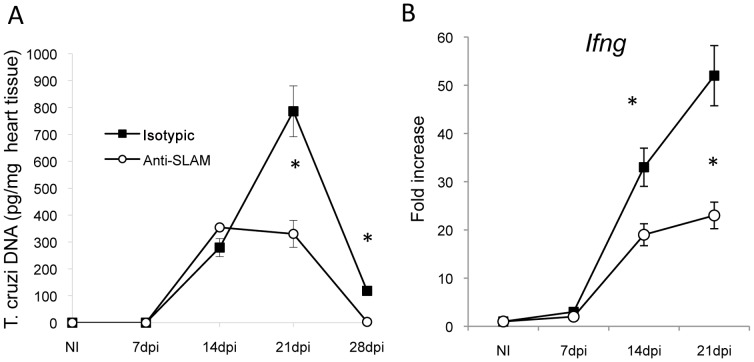

A monoclonal antibody directed against Slamf1 reduces the number of T. cruzi amastigotes in the heart

To test this concept we employed an alternative approach, namely administering an anti-Slamf1 monoclonal antibody to infected BALB/c mice once a week during the four weeks post infection with T. cruzi. We used a lower parasite inoculum than in Slamf1 KO mice in order to increase the survival and to allow the action of the antibody. Based on analysis of parasite DNA (Figure 7), the number of amastigotes in the heart was significantly reduced in antibody treated mice as compared to mice that had received an isotype control. In addition IFNγ mRNA levels were also partially reduced in a similar fashion. As in the Slamf1−/− mouse the monoclonal antibody directed against Slamf1 did not affect the parasitemia in the blood (data not shown). Thus, the antibody experiments directly support the conclusions that are based upon the experiments obtained with Slamf1−/− mice.

Figure 7. Anti-Slamf1 antibodies reduce heart parasite load.

BALB/c or Slamf1−/− mice were intraperitoneally infected with 1×102 trypomastigotes of the T. cruzi Y strain and treated with anti Slamf1 or control antibodies (0.5 mg/mouse once a week). At different dpi mice were sacrificed. A) T. cruzi DNA was quantified in the heart tissue of infected mice and expressed as the number of picograms of parasite DNA per milligram of DNA obtained from a heart tissue sample. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates of pooled DNA from 5 different mice. A representative experiment of the 2 performed is shown. B) IFN-γ mRNA production in the heart of T. cruzi infected mice. Total RNA was isolated in heart tissue at different dpi, and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the logarithm of relative quantity (RQ) calculated from comparative threshold cycle values, as described in Material and Methods. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

Discussion

The current studies led the concept that Slamf1 is required for replication of T.cruzi in macrophages and DCs, but not in other cells, which do not normally express the receptor, e.g. cardiomyocytes. Besides, in the absence of Slamf1, macrophages and DCs produce less myeloid cell specific factors that are key in influencing the host response to parasite and eventually the outcome of the infection. This explains why T. cruzi infected Slamf1−/− mice do not succumb to myocarditis induced by a lethal challenge with the highly virulent T. cruzi Y strain quite the opposite to BALB/c mice even with similar parasitemia levels. The later also indicates that parasitemia does not necessarily need to be related to cardiomyopathy, which is the leading cause of death upon T.cruzi infection in most instances [2], [9].

Our results also show that the systemic alterations previously reported associated to T. cruzi infection and suggested to play a role in pathology as impairment of thymocyte development [28], [32] or altered systemic cytokine production, among others [9], were not different in both infected Slamf1−/− mice and control Slamf1+/+ mice, indicating that those major changes in systemic immune responses are not responsible for the reduced susceptibility of Slamf1−/− mice to T. cruzi infection. Rather, the altered local heart response to infection, with much lower T. cruzi amastigotes and altered immune mediators in infected Slamf1−/− mice, are the most likely cause for the survival of Slamf1−/− mice upon an acute infection by the parasite.

We favor an interpretation of our observations that in Slamf1−/− mice less T. cruzi parasites enter the heart. However, as circulating parasite levels are similar in Slamf1−/− mice and the in vitro susceptibility of cardiomyocytes to infection is not altered by Slamf1 deficiency, is likely that T. cruzi blood trypomastigotes are unable to penetrate the heart directly to infect the cardiomyocytes. On the other hand, T. cruzi replicate much less well in Slamf1−/− DC and macrophages than in the equivalent wt cells. Although Slamf1 is expressed on the surface of hematopoietic stem cells, a careful analysis of Slamf1−/− on two genetic backgrounds has not revealed any abnormalities in hematopoiesis included myeloid cells [23], [27]. It is therefore unlikely that a major defect in myeloid development and differentiation in Slamf1−/− mice has an effect on T.cruzi infection.

Thus, despite comparable infiltration of macrophages and DCs between infected Slamf1−/− mice Slamf1−/−, the number of infective amastigotes that are carried into the heart by infected migrating Slamf1−/− monocytes, DCs or macrophages will be greatly reduced and might be one of the contributing factors to the survival of Slamf1−/− mice to infection with the parasite. In addition, it is also possible that homing of infected monocytes or macrophages into the heart is affected by the absence of Slamf1. Together, our results suggest that DC and myeloid cells can act as a “Trojan horse” for T. cruzi infection into the heart.

An alternative interpretation is that the reduced amastigote number in the heart of Slamf1−/− mice is a result of a stronger response to T. cruzi that limits its replication. Collectively, our results argue against this, since immune cells infiltrate the heart of a Slamf1−/− mouse in a similar fashion as in a BALB/c mouse and the amounts of key cytokines produced in the heart are equal or lower than in the wt mouse. Thus, although IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells may enter the heart from the circulation to eliminate T. cruzi infected cells [33], in Slamf1−/− mice similar numbers of CD8 cells infiltrate the heart, but produce less IFNγ due to lower antigenic stimulus. Moreover, arginase I levels are lower in the heart of Slamf1−/− mice, and we have found that the levels of this enzyme presents in infiltrating myeloid suppressor cells correlate with higher susceptibility to infection [31]. This reduction may also contribute to explain the lower susceptibility of Slamf1−/− mice.

Parasitemia levels are similar in both mice strains. This fact suggests that circulating parasite levels are mostly due to replication of T. cruzi in other organs and cells others than myeloid cells. T. cruzi are known to replicate in many cell types, including muscle, epithelial and endothelial cells [9], [34]. Since Slamf1 is only expressed in myeloid cells, the replication of T. cruzi in non-hematopoietic cells is not likely to be impaired in Slamf1−/− mice and hence the blood-borne parasitemia is only slightly less in the mutant mice.

Previously, Slamf1 was found to be a requisite for the elimination of the T. cruzi-related intracellular protozoa (Leishmania major) by B6 mice [23]. However, Slamf1−/− BALB/c mice respond to a L. major infection in an identical fashion as wt BALB/c animals. The role of Slamf1 in the response to the two related parasites is therefore different, as Slamf1 plays a detrimental role in T. cruzi infection of BALB/c mice. Consequently the mechanisms involved are likely to be different. In Leishmania infection the susceptibility of Slamf1−/− mice has been linked to a depressed NO production by macrophages, with a consequent inability to eliminate the parasite. NO is also required for T. cruzi killing [10] and we also found that T. cruzi infection in Slamf1−/− macrophages does not trigger iNOS, but this has no apparent impact for “in vitro” or “in vivo” replication. The reasons for this apparent discrepancy may lie in the fact that Slamf1 affects a different and earlier process in the infection of macrophages by T. cruzi than L. major, as the two parasites invade the cells by different mechanisms.

Besides, Slamf1−/− mice are also more susceptible to an attenuated strain of S. tyhimurium Sseb-e [27] contrary to T. cruzi. Although it might at face value appear paradoxical those contrasting effects one should keep in mind that in humans Slamf1 is one of the two receptors (probably the original receptor) for Measles virus [26], [27]. Therefore the virus and the parasite utilize an important receptor system to their advantage.

The diminished replication of T. cruzi in Slamf1−/− myeloid cells may explain, at least partially, the lower susceptibility of Slamf1−/− mice. Although, the mechanism by which Slamf1 reduce T. cruzi replication has not been addressed in this manuscript, previous experiments demonstrated that Slamf1 is involved in entering E.coli into phagosome, where it governs phago-lysosomal maturation and NADPH-oxidase (Nox2) activity [27]. This is caused by a reduction in of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-phosphate production, which is synthesized by the intracellular Class II PI3-kinase (PI3K) Vps34. As T. cruzi requires phagosome formation and PI3K (Vps34) activation to invade macrophages [17], [35], it is therefore likely that Slamf1 participates with other molecules/receptors in the entry of T. cruzi into the phagosome.

Moreover, a recent study shows that Nox2 inhibition ameliorates T. cruzi-induced myocarditis independently of parasitemia levels [36] as in Slamf1−/− mice. Thus, a reduced Nox-2 production together with a reduced replication in myeloid cells are the underlying mechanisms, which may explain the survival of Slamf1−/− mice to T.cruzi infection.

Interestingly, anti-Slamf1 treatment might affect the same processes. Consequently, Slamf1 is a key molecule in T. cruzi infectivity and represents an attractive novel therapeutic target for modulating T. cruzi infection and Chagas' disease.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The animal research described in this manuscript complied with Spanish (Ley 32/2007) and European Union legislation (2010/63/UE). The protocols used were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Centro de Biologia Molecular and Universidad Autonoma de Madrid.

Parasites, mice and infections

T. cruzi Y strain epimastigotes were cultured in liver-infusion tryptose medium (LIT) supplemented with 10% FCS. Epimastigotes were differentiated into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in GRACE medium (GIBCO BRL, Gran Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FCS for 10–12 days as described [17]. Blood trypomastigotes were maintained by weekly i.p. inoculations to BALB/c mice in our animal facilities. Six to 8-week-old BALB/c and Slamf1−/− mice [23], crossed 10 times with BALB/c mice as described, were maintained under pathogen-free conditions. Mice were infected i.p with 2×103 typomastigotes of the Y strain and parasitemia was measured as described [37]. Animals were also infected i.p with 1×102 typomastigotes and treated with the rat-anti-mouse Slamf1 antibody (9D1) or control rat antibody; 0.5 mg/mouse before the infection and then once a week.

Cell cultures and infection

Neonatal, mouse primary cardiomyocyte cultures were obtained as described [30], [38]. More than 90% of cells were cardiomyocytes as detected by immunostaining with antibody to mAchR M2 as described [39]. After 24 h, the cultures were infected with T. cruzi as described. Spleen from infected or control mice were isolated as described [17]. Thymic cells were also obtained as described [40] and cells harvested and centrifuged three times in phosphate buffered saline containing 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and 0.1% sodium azide. Later they were analyzed by flow cytometry using double immunofluorescence staining with phycoerythrin (PE)-anti-CD4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-CD8α (Becton Dickinson).

Spleen cells were stained for flow citometry using monoclonal antibodies against CD45R/B220, CD11b, CD11c, CD4 and CD8 (BD Biosciences). All samples were acquired in a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysed by using Flowjo 4.1 software (Tree Star, Inc).

Peritoneal cells from infected mice were collected with 0.34 M sucrose. Cells were then plated in complete RPMI with 5% FBS. After 4 h, non-adherent cells were removed by washing three times with warm PBS, and fresh complete RPMI was restored. Cells were analyzed by Giemsa staining under a light microscope. For in vitro infection, primary macrophages were isolated by peritoneal lavage of mice 4 days after a single intra-peritoneal injection of 10% thioglycolate solution (1 ml; Difco Laboratories). Cells (1.5×106/well) were allowed to adhere for 1 h in 12-well flat-bottomed plates in RPMI 0,5% FCS. Cells were co-cultured with T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes (10 parasites/cell) for 4 h to allow binding and internalization and macrophages were washed with PBS four times to remove unbound parasites. Cells were analyzed 24 h and 48 h post infection for gene expression by RT-PCR or cytokine production by ELISA in the supernatants. IL-2, IL-12, IL-10, IFN-γ, TNF, IL-6, IL-17A and IL-4 in cell culture supernatants or in serum samples were evaluated using ELISA kits from R&D systems following manufacturer instructions.

Dendritic cells were obtained from bone marrow from the femur and tibia of mice was flushed of the hind limbs with ice cold PBS (phosphate-buffered saline), was centrifuged and resuspended into RPMI 1640 (GIBCO) 5% FBS (complete medium) supplemented with 20 ng/ml of recombinant murine GM-CSF (Peprotech) at 37°C, 5% CO2. Each three days 25 ml fresh medium was added with the same concentration of GM-CSF. At day 7 the medium was collected, centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in fresh medium. 1×106 cells were plated in 6- well plates overnight in complete medium. Then, the cells were co-cultivated with T. cruzi trypomastigotes (10 parasites/cell) for 4 hours. After this time the cells were washed to remove the remaining parasites and they were incubated in fresh complete medium for the indicated time.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in NP-40 buffer (20 mM Tris- Hal pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mom Nail, 0.5% deoxyglycolate, 0.1% SDS and 10 mM NaF; the protease inhibitors aprotinin and leupeptin at 2 mg/ml, 1 mg/ml pepstatin and 1 mM PMSF; and 100 mM of the phosphatase inhibitor Na3VO4) for 30 min at 4°C, and supernatants were collected after centrifugation. The extracts (20 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) and subjected to Western blot with the appropriate antibodies for 1 h. Membrane was incubated with secondary antibody coupled to peroxidase and was revealed by Supersignal reagent (Pierce) and protein detected by autoradiography.

Real time PCR for parasite DNA detection and mRNA analysis by quantitative RT-PCR

Parasite DNA was isolated from heart tissue after blood perfusion with the High Pure PCR Template preparation Kit (Roche) and PCR reactions were conducted with 100 ng of the DNA as described [31]. For T. cruzi detection, we followed the method described by Peron et al. [41]. Heart RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen).Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was done with High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems) and amplification of different genes (ArgI, inos2, B220, CD11c, CD4, CD8, CD68, Ifng, Tnf, il4, il10, il13, il12, ptgs2 and 18SrRNA) was performed in triplicate using TaqMan MGB probes and the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI PRISM 7900 HT instrument (Applied Biosystems) as described [30]. Quantification of parasite DNA and gene expression by real-time PCR was calculated by the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method, normalized to the ribosomal 18S control and efficiency of the reverse transcription reaction (RQ = 2−ΔΔC T). (Fold-change). Graphs were plotted as log RQ when indicated.

Creatine Kinase (CK) assay

The activity of CK-MB isoenzyme, one of myocardial injury marker, was measured with commercial kits (EnzyChrom – ECPK-100, BioAssay Systems, USA) as described by the supplier. Incubation of serum samples with the substrate led to a net increase in NADPH concentration, directly proportional to the enzyme activity in the samples. The assay was adapted for reading in a microplate spectrophotometer (Microplate Nunclon Surface; FLUOstar Optima-BMG-Latch), to allow the study of small quantities of mouse serum according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The optical density at 340 nm was recorded at 10 min and again at 40 min.

Histological analysis of heart

The hearts of mice infected or not were fixed in 10% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal cuts of 5 µm thick were mounted on glass slides and stained with Haematoxylin-Eosin. The number of amastigote nests was estimated by observing 20 fields per preparation (each in triplicate) using the Lexica light microscope at a resolution of 630×. Hearts were also analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence as described [30]. Briefly, hearts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS solution, incubated in 30% sucrose solution, embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura) and frozen. Incubation with the following antibodies was done at 4°C: rat anti–mouseCD68-Alexa 594 (Serotec), goat anti- mouse CD11c-Alexa 555 (Santa Cruz), rat anti-mouse CD4-Alexa 647 (BD Pharmingen) and rat anti-mouse CD8-Alexa 594 (e-Bioscience). Images were obtained using an LSM510 Meta.

Statistical analysis

For in vivo experiments, data reported are means ± SD from triplicate determination of a representative experiment out of at least three (n≤5). Results shown from in vitro experiments are representative of at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was evaluated by Student's two-tailed t-test; all differences mentioned were significant compared to controls (p<0.05 or p<0.01).

Supporting Information

Spleen cell populations in infected mice. Splenocytes were isolated from thymus from control NI or T. cruzi infected BALB/c or Slamf1−/− mice at 14 and 21 dpi. The percentage of major leukocyte subpopulations in the spleen was assessed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates and from 5 different mice in each group.

(TIF)

Heart cytokine production by T. cruzi infected mice. Cytokine mRNA production in the heart of T. cruzi infected mice was evaluated by QC-PCR as described in Methods. Total RNA was isolated in heart tissue obtained from BALB/c and Slamf1−/− mice at different days post infection (dpi), and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the logarithm of relative quantity (RQ) calculated from comparative threshold cycle values, as described in Material and Methods.

(TIF)

Cytokine production in the serum of infected mice. The levels of different cytokines (IFN- γ, TNF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-17A) were quantified in blood of control and infected mice by flow cytometry following the instructions indicated by the supplier (Cytometric Bead Array-Becton Dickinson). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates from 3 different mice. A representative experiment of the 3 performed is shown. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

(TIF)

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was supported in part by grants FIS (PI040993), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2005-02220, SAF2007-61716 and SAF2010-18733), European Union (Eicosanox and ChagasEpiNet), CSIC-CONICET, BSCH/UAM, Comunidad de Madrid S2010/BMD-2332, RED RECAVA RD06/0014/1013 and RED RICET RD06/0021/0016 to MF, a grant from the NIH to CT (AI-15066), and an institutional grant of Fundacion Ramon Areces. J.C. is a holder of a fellowship from the Government of Panama. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chagas C. Nova tripanozomiaze humana. Estudos sobre a morfolojia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schitrypanum cruzi n. gen., n. sp. Ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homen. Mem Inst Oswal Cruz. 1909;1:159–219. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rassi A, Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez de Ayala A, Perez-Molina JA, Norman F, Lopez-Velez R. Chagasic cardiomyopathy in immigrants from Latin America to Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:607–608. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.080938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burleigh BA, Andrews NW. The mechanisms of Trypanosoma cruzi invasion of mammalian cells. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:175–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida N. Molecular basis of mammalian cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2006;78:87–111. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652006000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brener Z. Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1973;27:347–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.27.100173.002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed SG. Immunology of Trypanosoma cruzi infections. Chem Immunol. 1998;70:124–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teixeira MM, Gazzinelli RT, Silva JS. Chemokines, inflammation and Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:262–265. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girones N, Cuervo H, Fresno M. Trypanosoma cruzi-induced molecular mimicry and Chagas' disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;296:89–123. doi: 10.1007/3-540-30791-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munoz-Fernandez MA, Fernandez MA, Fresno M. Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma on macrophage activation for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:301–307. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fresno M, Kopf M, Rivas L. Cytokines and infectious diseases. Immunol Today. 1997;18:56–58. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)30069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, Martins-Filho OA, Gazzinelli G, et al. Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas' disease is due to a Th1-specific immune response. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1185–1193. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1185-1193.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Diego J, Punzon C, Duarte M, Fresno M. Alteration of macrophage function by a Trypanosoma cruzi membrane mucin. J Immunol. 1997;159:4983–4989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonay P, Fresno M. Characterization of carbohydrate binding proteins in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11062–11070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grellier P, Vendeville S, Joyeau R, Bastos IM, Drobecq H, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi prolyl oligopeptidase Tc80 is involved in nonphagocytic mammalian cell invasion by trypomastigotes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47078–47086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazzinelli RT, Denkers EY. Protozoan encounters with Toll-like receptor signalling pathways: implications for host parasitism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:895–906. doi: 10.1038/nri1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maganto-Garcia E, Punzon C, Terhorst C, Fresno M. Rab5 activation by Toll-like receptor 2 is required for Trypanosoma cruzi internalization and replication in macrophages. Traffic. 2008;9:1299–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howie D, Okamoto S, Rietdijk S, Clarke K, Wang N, et al. The role of SAP in murine CD150 (SLAM)-mediated T-cell proliferation and interferon gamma production. Blood. 2002;100:2899–2907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Wang N, Gullo C, et al. SAP controls T cell responses to virus and terminal differentiation of TH2 cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:410–414. doi: 10.1038/87713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan B, Lanyi A, Song HK, Griesbach J, Simarro-Grande M, et al. SAP couples Fyn to SLAM immune receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:155–160. doi: 10.1038/ncb920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engel P, Eck MJ, Terhorst C. The SAP and SLAM families in immune responses and X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:813–821. doi: 10.1038/nri1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veillette A, Cruz-Munoz ME, Zhong MC. SLAM family receptors and SAP-related adaptors: matters arising. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang N, Satoskar A, Faubion W, Howie D, Okamoto S, et al. The cell surface receptor SLAM controls T cell and macrophage functions. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1255–1264. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols KE, Ma CS, Cannons JL, Schwartzberg PL, Tangye SG. Molecular and cellular pathogenesis of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:180–199. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cannons JL, Tangye SG, Schwartzberg PL. SLAM family receptors and SAP adaptors in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:665–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2000;406:893–897. doi: 10.1038/35022579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger SB, Romero X, Ma C, Wang G, Faubion WA, et al. SLAM is a microbial sensor that regulates bacterial phagosome functions in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:920–927. doi: 10.1038/ni.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Meis J, Morrot A, Farias-de-Oliveira DA, Villa-Verde DM, Savino W. Differential regional immune response in Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez AR, Roggero E, Nicora A, Palazzi J, Besedovsky HO, et al. Thymus atrophy during Trypanosoma cruzi infection is caused by an immuno-endocrine imbalance. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:890–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuervo H, Pineda MA, Aoki MP, Gea S, Fresno M, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase and arginase expression in heart tissue during acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice: arginase I is expressed in infiltrating CD68+ macrophages. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1772–1782. doi: 10.1086/529527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuervo H, Guerrero NA, Carbajosa S, Beschin A, De Baetselier P, et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Infiltrate the Heart in Acute Trypanosoma cruzi Infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:2656–2665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savino W. The thymus is a common target organ in infectious diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padilla AM, Bustamante JM, Tarleton RL. CD8+ T cells in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall BS, Tam W, Sen R, Pereira ME. Cell-specific activation of nuclear factor-kappaB by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi promotes resistance to intracellular infection. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:153–160. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caradonna KL, Burleigh BA. Mechanisms of host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. Adv Parasitol. 2011;76:33–61. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385895-5.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhiman M, Garg NJ. NADPH oxidase inhibition ameliorates Trypanosoma cruzi-induced myocarditis during Chagas disease. J Pathol. 2011;225:583–596. doi: 10.1002/path.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alcina A, Fresno M. Activation by synergism between endotoxin and lymphokines of the mouse macrophage cell line J774 against infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasite Immunol. 1987;9:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GW, Schuschke DA, Kang YJ. Metallothionein-overexpressing neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes are resistant to H2O2 toxicity. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H167–175. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aoki MP, Guinazu NL, Pellegrini AV, Gotoh T, Masih DT, et al. Cruzipain, a major Trypanosoma cruzi antigen, promotes arginase-2 expression and survival of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C206–212. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendes-da-Cruz DA, de Meis J, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Savino W. Experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection alters the shaping of the central and peripheral T-cell repertoire. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:825–832. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piron M, Fisa R, Casamitjana N, Lopez-Chejade P, Puig L, et al. Development of a real-time PCR assay for Trypanosoma cruzi detection in blood samples. Acta Trop. 2007;103:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spleen cell populations in infected mice. Splenocytes were isolated from thymus from control NI or T. cruzi infected BALB/c or Slamf1−/− mice at 14 and 21 dpi. The percentage of major leukocyte subpopulations in the spleen was assessed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates and from 5 different mice in each group.

(TIF)

Heart cytokine production by T. cruzi infected mice. Cytokine mRNA production in the heart of T. cruzi infected mice was evaluated by QC-PCR as described in Methods. Total RNA was isolated in heart tissue obtained from BALB/c and Slamf1−/− mice at different days post infection (dpi), and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the logarithm of relative quantity (RQ) calculated from comparative threshold cycle values, as described in Material and Methods.

(TIF)

Cytokine production in the serum of infected mice. The levels of different cytokines (IFN- γ, TNF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-17A) were quantified in blood of control and infected mice by flow cytometry following the instructions indicated by the supplier (Cytometric Bead Array-Becton Dickinson). Results are expressed as the mean values (±SD) for triplicates from 3 different mice. A representative experiment of the 3 performed is shown. (*) Statistically significant differences between Slamf1−/− mice and BALB/c (p>0.05).

(TIF)