Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to assess the methodology and content of nutrition education during gastroenterology fellowship training and the variability among the different programs.

Methods

A survey questionnaire was completed by 43 fellowship training directors of 62 active programs affiliated to NASPGHAN, including sites in the United States, Canada and Mexico. The data were examined for patterns in teaching methodology and coverage of specific nutrition topics based on Level 1 training in nutrition, which is the minimum requirement according to published NASPGHAN fellowship training guidelines.

Results

The majority of the teaching was conducted by MD degree faculty (61%), and most of the education was provided through clinical care experiences. Only 31% of Level 1 nutrition topics were consistently covered by more than 80% of programs, and coverage did not correlate with the size of the programs. Competency in nutrition training was primarily assessed through questions to individuals or groups of fellows (77 and 65%, respectively). Program directors cited a lack of faculty interested in nutrition and a high workload as common obstacles for teaching.

Conclusions

The methodology of nutrition education during gastroenterology fellowship training is for the most part unstructured and inconsistent among the different programs. The minimum Level 1 requirements are not consistently covered. The development of core curriculums and learning modules may be beneficial in improving nutrition education.

Keywords: Pediatric gastroenterology fellowship, Fellowship training, nutrition education

INTRODUCTION

In the field of pediatric gastroenterology, general knowledge of nutrition, including nutritional assessment and nutrition support is an essential component of every patient’s care. Often nutrition support takes on a primary role in the management of diseases common to the pediatric gastroenterologist such as pancreatitis, pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, short bowel syndrome, chronic liver disease, and liver and small bowel transplantation [1].

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) has recognized the importance of nutrition education. In 1999, NASPGHAN published broad guidelines for training in pediatric gastroenterology [2]. These guidelines provide a core curriculum that defines the minimum knowledge and technical skills required of fellows upon graduation. Within these guidelines, the nutrition curriculum distinguishes between Level 1 of training which is the basic training required for all trainees (Table 1), and Level 2 which defines an advanced curriculum for the fellow who intends to become an “Expert in Nutrition”. For completion of Level 2, the guidelines suggest a minimum of one year of advanced training at an academic center under the supervision of a full time faculty in nutrition, and participation in basic or clinical research in nutrition. Level 2 is intended for trainees who plan to conduct research in the area of nutrition or direct a Nutrition Support Service.

Table 1.

List of topics covering Level 1 training requirements

|

MAC = midarm circumference, TSF=triceps skinfold thickness, ERD=gastroesophageal reflux disease

In order to assess the status of nutrition education during fellowship training, the NASPGHAN Nutrition Committee surveyed the affiliated fellowship training programs in 2008. The goal of the survey was to assess the methodology and content of nutrition education and the variability of training among the different programs. Ultimately, it is hoped this knowledge will help NASPGHAN enhance the consistency among programs and refine the nutrition curriculum in order to meet the needs of the membership, the trainees and our patients.

METHODS

A survey was created utilizing an Excel spreadsheet. Questions and style for the survey were developed through discussions with members of the NASPGHAN Nutrition Committee as well as outside advisors with expertise in surveys who assisted in determining the appropriate content and structure of the questionnaire. Earlier iterations were piloted with members of the Nutrition Committee and the advisors. The types of questions and their wording were refined until consensus was achieved on the optimal questionnaire version which then was used in the survey. The questionnaire was composed of 42 questions that were answered by drop-down menu, and it also included a section where program directors were specifically asked to make comments regarding the obstacles faced in teaching nutrition and suggestions for NASPGHAN to help improve nutrition education. The questions were based on the NASPGHAN Guidelines, and specifically Level 1 requirements in nutrition education [2]. The questionnaire was distributed via electronic mail to the fellowship program training directors of all the affiliated programs in 2008 and 2009. Follow up e-mails and phone calls then were made to those program directors who had not responded to the initial request. Data are reported as mean ± SD and frequency (%) when applicable. Correlations are computed with Pearson’s method, and their 95% confidence intervals are also reported. All statistical analyses are conducted with R 2.13.0 [3].

RESULTS

Of the 65 programs listed, 3 programs responded that they did not have any fellows at the time and so were considered inactive. Of the 62 active programs, 43 completed and returned the survey and 19 did not respond. Thus, there was a 69% overall response, which included 36 of 50 United States programs, 4 of 7 Canadian programs, and 3 of 5 Mexican programs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Programs’ Demographics.

| USA | Canada | Mexico | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Number of Program Responses (% of total) | 36 (72%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (60%) |

|

| |||

| Number of Programs per Region: | |||

| South | 9 | ||

| Northeast | 12 | ||

| Midwest | 13 | ||

| West | 2 | ||

|

| |||

| Number of Fellows per Program | 4.7 ± 3.0# | 12, 5, 1, 3* | 8, 4, 5* |

|

| |||

| Number of Faculty per Program: | |||

| MD | 7.4 ± 6.5 | 8, 5, 6, 0 | 4¶ |

| MD/PhD and PhD | 0.8 ± 1.9 | 3, 1, 0, 1 | 0 |

| Masters | 0.6 ± 2.5 | 1, 1, 1, 4 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Percentage of Programs with a Nutrition Board Certified Educator: | |||

| MD | 42.4 | 0 | 0 |

| MD/PhD and PhD | 6.2 | 2 | 0 |

| RD | 54.5 | 25.0 | 0 |

Mean ± SD

For programs in Canada and Mexico, all data are presented

Only 1 Mexican program provided information regarding the academic degrees of its faculty

The programs’ demographics are shown in Table 2. Programs from the US, Canada and Mexico showed a similar number of fellows per program. There was a wider distribution in the number of faculty among the programs. Approximately half of the US MD and dietary faculty had some certification in nutrition (e.g. Clinical Nutrition Certification Board, American Clinical Board of Nutrition), and among 33 US programs providing information, 24 (67%) had at least 1 certified faculty.

Survey questions relating to nutrition education are summarized in Table 3. MD degree faculty provided the majority (61% ± 27%) of teaching but a substantial minority of teaching was provided by registered dietitians (RD). Teaching through clinical care provided the largest percentage of teaching opportunities with problem-based learning providing the smallest. Competency was assessed through multiple means, but written tests (35%) were less likely to be used than oral questions to individual fellows (77%) or to groups of fellows (65%). Although not clarified further on the survey questionnaire, oral questions in the context of the options provided are meant as less formal questions such as those asked during clinical rounds or conferences. The majority of the programs (74%) reported that fellows had the opportunity to participate in nutrition related research projects. Data regarding the number of fellows who pursued these opportunities were not collected nor did we obtain the number of fellows who pursued Level 2 training as we were concerned with the time burden these additional questions would pose to the fellowship training directors and the resultant adverse impact on response rate.

TABLE 3.

Nutrition Education Methodology.

| USA (n=36) | Canada (n=4) | Mexico (n=3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Percentage taught by: | |||

| MD | 60.9 | 51.2 | 80.0 |

| MD/PhD | 8.2 | 22.5 | 3.3 |

| PhD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Masters | 0.4 | 3.8 | 0 |

| RD* | 30.5 | 22.5 | 16.7 |

|

| |||

| Percentage taught through: | |||

| Lectures | 20.0 | 17.5 | 19.0 |

| Clinical Care | 57.1 | 58.7 | 48.3 |

| Directed Reading | 12.4 | 12.5 | 20.3 |

| Problem Based | 10.5 | 11.3 | 12.4 |

|

| |||

| Competency Assessments through:# | |||

| Written Tests | 12 (33.3) | 1 (25) | 2 (66.6) |

| Questions to Individual Fellows | 28 (77.7) | 4 (100) | 1 (33.3) |

| Questions to Groups of Fellows | 23 (63.8) | 4 (100) | 1 (33.3) |

| Other (e.g. Presentations, etc) | 26 (72.2) | 2 (50) | 2 (66.6) |

Registered Dietician

Indicated as number (percentage of total respondents); competency assessments are not mutually exclusive

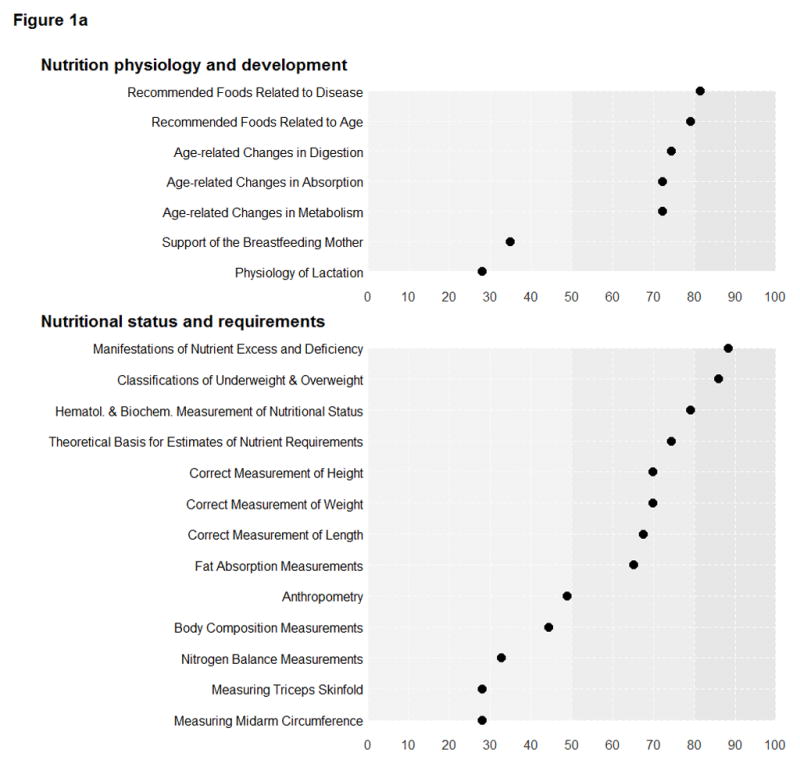

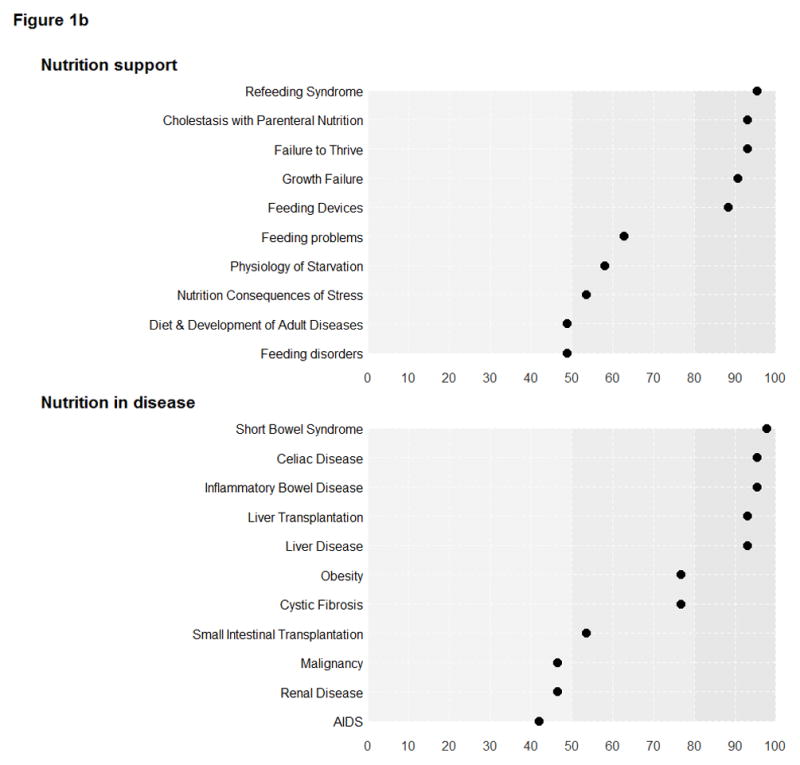

Questions concerning specific topics covered as part of Nutrition education training are summarized in Figure 1. For the purpose of this summary, the topics are grouped into 4 broad categories. The topics covered by 80% or more of the programs are considered to be “Consistently Covered”, those covered by 50 to 79% of programs are considered “Somewhat Consistently Covered” and those covered by less than 50% are considered “Inconsistently Covered”. In the category of “Nutrition and Development” only the topic of Recommended Foods Related to Disease was covered consistently, and the 2 topics that were inconsistently covered were Support of the Breastfeeding Mother and Physiology of Lactation. For the category titled “Assessment of Nutritional Status and Estimation of Nutrient Requirements,” 2 topics were consistently covered, Clinical Manifestations of Nutrient Excess and Deficiency and Classifications of Overweight and Underweight. Within this category, 5 topics were inconsistently covered, namely Anthropometry, Body Composition Measurements, Nitrogen Balance Measurements, Triceps Skinfold and Midarm Circumference Measurements. Under the category “Nutrition Support” the topics covered the least include the Role of Diet in the Development of Adult Diseases and Management of Feeding Disorders. Finally, within the category “Nutrition in Disease” the topics inconsistently covered were Nutrition Issues and Management in Renal Disease, AIDS and Malignancy. The total number of topics covered at each program did not correlate with the number of faculty [correlation = 0.045, 95% confidence interval = (−0.27, 0.35), P = 0.78] or the number of fellows [correlation = −0.085, 95% confidence interval = (−0.38, 0.22), P = 0.59] per program.

Figure 1.

Percentage of programs that reported covering various topics. Figure 1 is divided arbitrarily into 1a and 1b for ease of viewing. Topics covered by 80% or more of the programs are considered to be “Consistently Covered” (darker shaded area), those covered by 50 to 79% of programs are considered “Somewhat Consistently Covered” and those covered by less than 50% are considered “Inconsistently Covered” (lighter shaded area).

Trainees often are able to rotate through specialized clinics or programs outside of their own GI division, thus, we evaluated the frequency with which this occurred. Out of a total of 43 responding programs, 29 (67%) reported utilization of specialized clinics as part of the fellowship training curriculum. The Home TPN Clinic (35%) and Feeding Team Clinic (30%) were the most common rotations. Other less common rotations included Cystic Fibrosis Clinic (21%), Weight Management Program (14%), Feeding Disorders Clinic (11%), Lipid Disorders Clinic (7%) and Bone Clinic (2%).

In order to evaluate the training in clinical nutrition support, a series of questions relating to enteral and parenteral nutrition (PN) were provided (data not shown). Of significance, only 65% of programs reported that general ward PN or feeding orders were written by their fellows. Whereas only 32% of programs allowed for fellows to write Pediatric Intensive Care Unit PN orders and 7% allowed for Neonatal Intensive Care Unit PN orders.

Finally, 26 of 42 programs (62%) completed the comments and suggestions section of the survey. The main obstacle reported was the lack of interested faculty and the high workload (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Challenges and Suggestions for Nutrition Teaching.

| What are the Greatest Obstacles to Teaching Fellows Nutrition? | n (%)* |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Interested faculty | 9 (35) |

| Workload | 8 (31) |

| Lack of curriculum | 2 (8) |

| Lack of nutritionists | 1 (4) |

| Lack of dedicated nutrition clinic | 1 (4) |

|

| |

| How can NASPGHAN Improve Nutrition Training? | n (%) |

|

| |

| Develop curriculum | 16 (62) |

| Computerized learning program | 7 (27) |

| Funding for nutrition research/training | 4 (15) |

| Review course for fellows | 3 (12) |

| Standardized reimbursement | 2 (8) |

| Liaising with other societies | 1 (4) |

n= number of respondents (% of 26 respondents)

DISCUSSION

Nutrition education is one of the pillars in the training of pediatric gastroenterologists. The NASPGHAN Guidelines provide a nutrition curriculum that sets out broad requirements for both a basic and an advanced level of nutrition training [2]. In order to understand how well these guidelines are being implemented, and understand the challenges to teaching nutrition, the fellowship program directors of NASPGHAN affiliated programs were surveyed. The survey was designed to address the demographics, the methodology and the content of teaching, particularly focusing on the published minimum requirements (Level 1).

Nutrition education should and is mainly handled by medical doctors. Although dietitians account for approximately 30% of the teaching in the US, they probably are underutilized in that at least half of the programs in the US have a nutrition support certified dietitian.

It should be noted that nutrition is not recognized as a medical subspecialty by national regulatory agencies such as the American Board of Medical Specialties. Certifications in nutrition and nutrition support are awarded to health care providers of different academic backgrounds by a number of organizations including the American Clinical Board of Nutrition (ACBN), the National Board of Nutrition Support Certification (NBNSC), the American Board of Physician Nutrition Specialists (ABPNS), and the Clinical Nutrition Certification Board (CNCB) after successful completion of exams that assess nutritional support competencies specifically.

The size of the program did not correlate with the overall coverage of nutritional topics. In fact, neither the number of faculty nor the number of fellows per program was significantly associated with the percentage of topics covered during training.

When considering the methodology of teaching, we found that nutrition is principally taught through clinical care with only 20% of programs reporting the use of lectures. This observation suggests that nutrition teaching during fellowship for the most part is unstructured. Indeed, several programs when asked to comment specifically identified the lack of a core curriculum as an important obstacle in teaching nutrition. The lack of structure may explain why a number of topics considered part of Level 1 training were covered by less than half of all reporting programs. These inconsistently covered topics include the support of the breastfeeding mother, the physiology of lactation, anthropometry and measurements of triceps skinfold and midarm circumference, body composition and nitrogen balance, the role of diet in the development of adult diseases and management of feeding disorders, the nutritional management in renal disease, AIDS and malignancy.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has published a list of tools to assist in competence assessment [4]. Perhaps the more commonly employed are global ratings of recorded performance, chart stimulated recalls, oral examinations, checklist evaluations, patient surveys, simulations and models, and written examinations. Each method has its strengths and limitations, and overall competence may be best measured through a combination of tools. Our survey showed that competence assessment was accomplished through a variety of methods, but mainly via less formal oral questions to individuals or groups of fellows as opposed to written tests.

The majority of programs report utilizing rotations in specialized clinics or programs as part of the fellows’ training in nutrition. Interestingly, some of these clinics seem to have a more important contribution than others to the teaching of specific nutritional topics. As such, the Feeding Team Clinic is one of the more commonly employed rotations, utilized by 30% of all programs, yet the topic of nutritional management of feeding problems is only somewhat consistently covered (63% of all programs), presumably primarily by bedside teaching. On the other hand, the Weight Management Clinic is one of the least common rotations (14% of programs); yet nutritional management of obesity is covered by 77% of all programs. These data suggest that other factors, such as the number of patients with a particular clinical problem the fellow is exposed to in all clinical settings, also may influence the coverage of nutritional topics.

Regarding clinical nutrition support, it is important to note that fellows are fairly well exposed to PN, though not uniformly since 84% of programs reported that fellows wrote PN orders. This percentage may be higher if one considers fellow participation in PN order decisions and not strictly order writing. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that fellows only wrote PN Intensive Care Unit (ICU) orders in 32% of programs. These numbers may be affected by the rules at a particular institution regarding the role of fellows vs residents in writing PN orders. Although there was no specific question addressing the topic of ICU nutrition, other related questions such as nutritional consequences of stress were only somewhat consistently covered (53% of programs).

Sobering, in our view, is that some respondents identified a lack of interested faculty and/or lack of nutritionists as obstacles to nutrition education. We presume a lack of interest may be more connected to a lack of time to provide formal nutrition education (e.g., lectures) rather than actual disinterest given that many of the faculty have some type of nutrition certification. Also noted were low reimbursements for nutrition consultations contrasted with financial incentives for procedure-based skills. These findings are similar to those previously reported in a survey of adult gastroenterology fellows regarding factors which prevented them from pursuing further training or research in nutrition. [5] The authors of this study identified the recruitment of a physician with expertise in nutrition as potentially the most beneficial step in improving nutrition training.

In view of the above findings, we have identified potential areas for improvement. First, it will be important to emphasize the minimum requirements as defined by the nutrition curriculum Level 1 training. Second, the creation of a lecture series or computerized learning modules could assist programs in providing a comprehensive and structured education in nutrition. Third, a structured competence assessment is of utmost importance as it benefits both trainees and programs. Fourth, it would be important to provide greater nutrition exposure emphasizing its clinical relevance and application as part of continuing medical education including at national meetings, including the NASGPHAN annual meeting. Finally, we hope that the current observations will assist in the revision of the Fellowship Training Guidelines which is an ongoing project.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the input of the 2007 NASPGHAN Nutrition Committee and Drs. Jenifer Lightdale and Anthony Otley in the development of the survey and Inderpreet Jalli for preparing the Excel file. Biostatistics services were provided by Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Digestive Disease Research Center supported by NIH grant DK058404. Support also was provided by the Daffy’s Foundation, the USDA/ARS under Cooperative Agreement No. 6250-51000-043, and P30 DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Disease Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work is a publication of the USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None disclosed

References

- 1.Duggan C. Nutritional Assessment and Requirements. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, Walker-Smith JA, editors. Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. 3. Ontario: BC Decker; 2000. pp. 1691–1705. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudolph CD, Harland SW the NASPGN Executive Council, NASPGN Training and Education Committee. NASPGN Guidelines for Training in Pediatric Gastroenterology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:S1–S26. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199911001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.R Development Core Team for the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Accessed December 1, 2011];R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/

- 4.ACGME. [Accessed July 18, 2011];Toolbox of Assessment Methods. 2000 Sep; Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/assess/Toolbox.pdf.

- 5.Scolapio JS, Buchman AL, Floch M. Education of Gastroenterology Trainees. First Annual Fellow’s Nutrition Course. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:122–127. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181595b6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]